Abstract

Recent advances in methodology help long-term in vitro maintenance of primary human hepatocytes (PHH), improving their predictability for drug-induced liver injury. Small-molecule additives, such as 5C, have been described to prolong hepatocyte functionality, however, comprehensive description of CYP enzyme and transporter functions are scarce. Here we show a new hepatic model developed by treating hepatocytes in sandwich configuration with 5C (SPHH-5C), where, besides keeping hepatocytes in a fully differentiated form, their polarization is also supported to achieve more in vivo-like structure. The model is characterized by CYP enzyme and hepatobiliary transporter expression and activity as a function of culture time. Hepatic functions were compared in untreated (SPHH) and 5C-treated sandwich (SPHH-5C) or monolayer cultures (PHH-5C). CYP enzyme and transporter functions were best retained in SPHH-5C cultures for 21 days. To simplify the experimental setup and reduce hepatocyte need, a substrate cocktail was applied for simultaneous uptake transporter (OATP1Bs, NTCP, OCT1, OAT2) activity measurements. Beside single donor lots, pooled hepatocyte lots were shown to be applicable for long-term culturing to mitigate interindividual variability. Our novel hepatic model provides a robust and reliable platform for drug screening and safety evaluation by extending in vitro functionality of hepatocytes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There is a strong need for reliable prediction of drug-induced liver injury (DILI) and drug-drug interaction (DDI) based on advanced in vitro methods. Both the historically high number of DILI- and DDI-related drug withdrawals, as well as an emerging knowledge of idiosyncratic hepatotoxicity associated with marketed drugs necessitate this demand1,2. Preclinical animal models are an indispensable part of drug development but species differences may result in misinterpretations1. Therefore, and in agreement with the present industry-wide policies to reduce or replace animal use (3R), there is an urge for improved in vitro models.

Currently, chronic toxicity prediction is heavily reliant on animal models; to obtain more reliable data in vitro, extended incubation times beyond the commonly used 4-24-hours would be necessary. Utility of the most routinely used sandwich-cultured primary human hepatocytes (SPHH)3 for the detection of harmful metabolites - especially slow-metabolized compounds - is limited. By using long-culture hepatocyte models, in vitro to in vivo extrapolation (IVIVE) could be improved4, as the hepatotoxic effects and the toxicodynamic responses can be characterized both as function of time and dose5,6.

Primary human hepatocytes (PHH) have been recognized as the gold standard for DILI prediction, however, their rapid dedifferentiation and loss of functions in culture limit the acceptability and interpretation of results7. The most intensively studied approaches to maintain in vivo-like hepatic functions are the following: spheroid and organoid cultures8,9,10,11, co-culturing hepatocytes with non-parenchymal cells and/or liver-sinusoidal endothelial cells12, stem cell derived (hiPSC) models13, organ-on-chip14, and the various combinations of the above15,16,17,18,19. All listed models are complex and sophisticated culture systems with numerous advantages; nonetheless, most of them are time- and labor-consuming, methodologically complex, and demand expensive apparatus, posing a limitation for their widespread use1,20,21. Another approach is to improve PHH model, where the hepatocytes sustain their functionally differentiated state by the modification of culture protocols21,22,23,24,25,26, or adding small molecules to efficiently inhibit the dedifferentiation processes27,28,29.

Among various combinations of small molecules demonstrated to inhibit dedifferentiation processes in PHH, the 5C model is the best characterized with regards of expression and activity of hepatobiliary transporters and metabolic enzymes. It helps to preserve hepatocyte-like characteristics by inhibiting epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT)29. The 5C cocktail contains: transforming growth factor- β (TGF-β) inhibitor (SB431542), which contributes to the maintenance of E-cadherin levels and intercellular contact among hepatocytes; forskolin, which inhibits the expression of EMT genes and maintains the expression of key hepatocyte genes such as ALB, CYP3A4, OTP1B1; Notch inhibitor (DAPT), Wnt inhibitor (IWT2) and LN193189, which are further inhibiting EMT induction30. This composition proved to be superior over other small molecular cocktails, namely “YPAC” and “SACY”, which also contained TGF-β inhibitor and Wnt signaling inhibitor27,28.

The aim of this study was to combine the advantages of 5C-treatment with culturing hepatocytes in sandwich configuration that would result in a more stable in vitro hepatic model suitable for long-term DDI, chronic and /or repeated dosing toxicology studies. Furthermore, compared to spheroid or organoid models, the costs, labor and time consumption preparing SPHH-5C culture is significantly lower and more straightforward, rendering it appropriate for high-throughput screening of drug candidates.

Results

Viability and functional characterization of hepatocytes

Cells were cultured in 2D monolayer (PHH) and in sandwich configuration (SPHH), and treated with 5C mixture (PHH-5C, SPHH-5C) from Day 1 (D1) through D21. To determine the effect of 5C treatment, the morphology and hepatic markers of PHHs were monitored. Secretion of urea and albumin, as well as LDH release, a common viability indicator, were measured in the medium.

SPHH-5C cultures maintained the in vivo-like polygonal morphology up to D21 (Supplementary Fig. S1). Urea and albumin secretion of hepatocytes cultured in any of the experimental conditions indicates that the cells did not lose their differentiated phenotypes throughout the experimental period; however, there were variations in excretion rates (Fig. 1a, b). In SPHH, the albumin secretion markedly increased by D4, then gradually decreased up until D21. On the contrary, in the presence of 5C, the elevation of albumin secretion was slower, and reached its maximum level on D7, and remained constant up to D21 (Fig. 1a).

Urea secretion was more stably preserved in hepatocytes treated with 5C compared to the untreated SPHH, although it decreased by D14 and remained constant in all cultures (Fig. 1b).

Following the somewhat higher LDH release on the first 2 days (D2), probably due to the recovery of the attached cells, the LDH concentration in the medium decreased markedly by D4 in all cultures, indicating that no substantial cell death occurred throughout the 21 days of the experiment (Fig. 1c).

mRNA expression of CYP enzymes and hepatobiliary transporters

The gene expression of cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes (CYP1A2, CYP2B6, CYP2D6, CYP2C8, CYP2C9, CYP2C19 and CYP3A4) and hepatic uptake transporters (OTP1B1, NTCP, OCT1, OAT2), efflux transporters (BCRP, BSEP, MRP2, MDR1, MDR3) was measured.

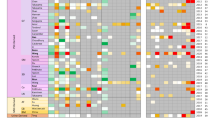

The most pronounced benefit of 5C treatment was observed in the mRNA expression of CYP enzymes. The mRNA level of CYP2B6 gradually decreased as a function of time in SPHH culture, and almost vanished by the end of the experiment. In contrast, the mRNA expression of CYP2B6, was significantly higher in SPHH-5C and PHH-5C cells. After the observed 70–80% decline in mRNA expressions measured at 4-hour after seeding (D0) compared to cells in suspension, a slow or negligible recovery was noted for every enzyme in SPHH cultures, except for CYP2C19. CYP2C19 and CYP2D6 expression was stable in all culture conditions until D21. 5C treatment resulted in a significant overexpression of all enzymes except CYP2D6, and the most pronounced increase was observed in CYP1A2 (~ 8-fold) and CYP3A4 mRNA levels (~ 15 and 25-fold in SPHH-5C and PHH-5C, respectively), which was sustained throughout the experimental period (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Fig. S2).

Heatmaps demonstrating alterations in the gene expression. Gene expression profile of (a) CYP enzymes and (b) hepatobiliary transporters in SPHH, SPHH-5C, and PHH-5C cultures up to 21 days. The relative expressions were normalized to the expression level of 18S rRNA. The data are presented as a fold change relative to the mRNA levels in the hepatocyte suspension prior to seeding (lot: single-donor hepatocytes, IRZ). Samples designated as D0 were collected 4 hours post-seeding, before any special culturing condition was applied.

Similarly to CYP enzymes, the mRNA expression levels of nearly all transporters exhibited a marked reduction on D0 compared to their expression observed within the hepatocyte suspension. The only exceptions were efflux transporters involved in xenobiotic elimination, namely BCRP, MRP2 and MDR1. By D7 of culturing, hepatocytes regained the original mRNA expressions of several transporters and were maintained stably until D21 in all cultures. BCRP, MRP2 and MDR1 mRNA levels were highly overexpressed compared to cell suspension in 5C treated cultures. Recovery of BSEP mRNA expression required an extended duration, and 5C treatment had a beneficial impact on it. On the contrary, OAT2 mRNA expression remained considerably below the original level in 5C-treated hepatocytes and was recovered only in SPHH cultures (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Fig. S3).

Functional characterization of CYP enzymes

The effect of 5C mix on the function of CYP enzymes (CYP1A2, CYP2B6, CYP2D6, CYP2C8, CYP2C9, CYP2C19 and CYP3A4) was measured using selective substrates in mixtures (Supplementary Table S1), both on single (Fig. 3, Supplementary Fig. S4) and pooled donor hepatocytes (Supplementary Fig. S4). 5C treatment was the most effective in case of CYP2B6, CYP2C9 and CYP2D6 (Fig. 3b, d, f). In SPHH-5C cultures, at D21 CYP2B6 enzyme activity was the same as in the hepatocyte suspension and was two orders of magnitude higher in 5C-treated cultures than in SPHH (Fig. 3b). CYP1A2, CYP2C9 and CYP3A4 activities were well preserved in all cultures measured, and interestingly, they somewhat increased by D4 in 5C-treated hepatocytes (Fig. 3a, d, g).

Activities of CYP enzymes in SPHH, SPHH-5C and PHH-5C hepatocyte cultures up to 21 days. The following CYP enzymes are presented: (a) CYP1A2, (b) CYP2B6, (c) CYP2C8, (d) CYP2C9, (e) CYP2C19, (f) CYP2D6 and (g) CYP3A4. D0 values are determined in the cell suspension before seeding. Representative graphs from single-donor hepatocytes (lot: IRZ). Data is presented as Mean ± SD (n = 3 of each condition). Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison tests (p < 0.05).

The most pronounced loss of activity was observed in CYP2C8, where it declined to 4.5, 8.5 and 3% in SPHH, SPHH-5C and PHH-5C by D4, respectively, and further decreased with time (Fig. 3c). The activity of CYP2C19 experienced a notable decline, however, the administration of 5C treatment demonstrated some advantageous effects in SPHH-5C. At 21 days of culturing, CYP2C19 activity was 6.7, 19.4 and 4% in SPHH, SPHH-5C and PHH-5C cultures, respectively, of that measured in the hepatocyte suspension (Fig. 3e). In conclusion, small molecule treatment was effective in maintaining the enzyme activity of CYP1A2, CYP2B6, CYP2D6, CYP2C9, CYP2C19 both in SPHH-5C and PHH-5C.

Functional characterization of hepatic uptake transporters

To determine whether 5C treatment affects hepatocyte uptake activity, we conducted a series of uptake clearance measurements. The four most relevant liver uptake transporters were evaluated using their known probe substrates, rosuvastatin for OATP1Bs, glycochenodeoxycholic acid (GCDC) for NTCP, sumatriptan for OCT1 and ketoprofen for OAT2. To reduce cellular utilization and streamline the experimental procedure, we enhanced the uptake methodology by using substrates in mixture. In preliminary experiments, we demonstrated that the substrates did not affect the uptake rate of each other, supported by similar uptake clearance values when applied either separately or in mixture (Table 1).

NTCP, using GCDC as substrate, exhibited significant differences in activity between the cultures. In SPHH-5C, it was sustained for D21 at a 1.6-fold higher level than it was on D0. In SPHH, the activity of NTCP was not stable during the culturing period (Fig. 4a, Supplementary Fig. S5).

Active uptake clearance values in SPHH, SPHH-5C and PHH-5C hepatocyte cultures up to 21 days. Specific uptake transporter substrates are the following: (a) GCDC for NTCP, (b) ketoprofen for OAT2, (c) rosuvastatin for OATPs, (d) sumatriptan for OCT1. Representative graphs from pooled-donor hepatocytes (lot: UDT). Data is presented as Mean ± SD (n = 3 of each condition). Two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison tests (p < 0.05).

Uptake clearance of ketoprofen by OAT2 was well preserved in SPHH and SPHH-5C cultures until D21. In SPHH-5C, following a 50% decrease measured on D4, uptake clearance was recovered by D7 and maintained until the end of the experiment. The OAT2 activity in PHH-5C culture also exhibited a significant reduction of 50% on D4 compared to D0, though, it persisted at a low level during the 21 days (Fig. 4b, Supplementary Fig. S5).

As expected, OATP1Bs activity continuously decreased in SPHH after D4. PHH-5C showed similar tendencies to those observed in SPHH. In contrast, the clearance of rosuvastatin through OATP1Bs remained relatively consistent in SPHH-5C cultures up to 3 weeks (Fig. 4c, Supplementary Fig. S5).

The activity pattern of OCT1 was closely resembled that of OATP1Bs. The uptake clearance of sumatriptan decreased to nearly 50% by D7 in both SPHH and PHH-5C, however, it was preserved in SPHH-5C culture up to D21 (Fig. 4d, Supplementary Fig. S5). Comparable results were obtained in single (Supplementary Fig. S4) and pooled donor hepatocytes (Fig. 4).

Functional characterization of biliary efflux transporters

We investigated the transport of 5(6)-carboxy-2’,7’-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (CDCF-DA) and tauro-nor-THCA-24-DBD (tauronor) to evaluate the function of biliary efflux transporters, MRP2 and BSEP, respectively, on single and pooled donor hepatocytes. Abundant canaliculi staining can be seen on D7 in all cultures (Fig. 5a, b, single donor not shown). 5C treatment had a beneficial effect on the maintenance of bile pockets; in SPHH-5C cultures these structures were maintained up to D21. On the contrary, the fluorescent CDCF signal in bile pockets was markedly reduced in SPHH and PHH-5C from D7 to D21 (Fig. 5a, c, Supplementary Fig. S6). MK-571 inhibited the efflux of CDCF in all cultures at all timepoints (Fig. 5a). While CDCF-DA enters the cells passively, tauronor requires NTCP activity for cellular entry, therefore tauronor signal further supports the function of uptake and efflux transporters. Similarly to the conclusions drawn from CDCF results, only SPHH-5C cells preserved their NTCP and BSEP activities up to D21 (Fig. 5b). Intracellular accumulation of tauronor was increased by cyclosporin A (CSA), a known inhibitor of BSEP.

Biliary efflux capacities of SPHH, SPHH-5C and PHH-5C hepatocyte cultures up to 21 days. The bile canaliculi are visualized by (a) CDCF and (b) tauronor, and the efflux is inhibited by MK-571 and cyclosporin A (CSA), respectively. (c) Fluorescent intensity of CDCF in the bile canaliculi. Data are expressed as sum of the individual intensity values. Data were analyzed by Revvity Harmony Software. Representative graphs from pooled-donor hepatocytes (lot: UDT, n = 2 of each condition). (a) 20x objective, green-CDCF, blue-Hoechst; (b) 63x water-immersion objective, green- tauronor, blue-Hoechst.

Discussion

Primary human hepatocytes (PHHs) are the gold standard for in vitro toxicity, DDI and DILI assessment, however, hepatocyte dedifferentiation and inter-donor variety due to genetic and epigenetic polymorphism, ageing and gender limit its applicability7,23. Recent advances have been made to maintain hepatocytes in their fully differentiated form, but direct comparisons of functional characterization with gene expression are scarce, and especially data on long-term preservation of transporter activity are lacking. Here we show for the first time the advantages of combining small molecule treatment with culturing in sandwich configuration and provide a comprehensive characterization of these cultures regarding hepatic function measurements useful for ADME-Tox and DILI predictions in the pharmaceutical industry.

In our study, we showed that by adding small molecule complex supplements to the medium, albumin and urea secretion and the viability are maintained up to 21 days, in agreement with others27,28,29.

Although there are many significant differences in the expression and activity of CYP enzymes and transporters across different cultures and time points, our main conclusions are based on general trends showing superior effect of SPHH-5C culturing.

The activity of the investigated CYP enzymes was in good correlation with their mRNA expression level and best preserved in SPHH-5C throughout the culturing time, except for CYP2C8 and CYP2C19 where the metabolic capacity was reduced. In addition, CYP3A4 and CYP1A2 overexpression did not resulted in an enhanced activity. In contrast to metabolic enzymes, gene expression of all transporters except OAT2 were recovered in all culture conditions after an initial decrease. BSEP, OATP1B1, MDR3, NTCP and OCT1 mRNA expressions regained their original values in SPHH-5C and SPHH. The uptake clearance was in good correlation with the gene expression of OATP1Bs, NTCP and OCT1, and was the highest in the presence of 5C on D21. In contrast, ketoprofen uptake clearance was observed at its highest levels in the SPHH and SPHH-5C cultures, however, it was also measurable within the PHH-5C culture (Table 2).

The marked decrease in the mRNA expression of all CYP enzymes at 4-hours after seeding (D0) compared to cell suspension is a well-documented phenomenon31. CYP2B6, CYP2C9 and CYP2C8 were recovered in 5C treated cells in contrast to SPHH. CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 regained the basal expression in all cultures. Consistent with our data, the mRNA expression levels of these Phase I enzymes were sustained in small molecule treated cultures for 40 days28,29,32. Changes in enzyme activity of CYP2B6, CYP2D6 and CYP2C9 correlated well with their mRNA expression under all experimental conditions. Overall, 5C treated cultures displayed more stable metabolic activity of CYP2B6 and CYP2D6 than SPHH. While CYP2C9 metabolic activity was well preserved in all cultures, better recovery was seen in 5C treated cells by D21. Consistent with our findings, others described that CYP2D6, CYP2B6 and CYP2C9 activity was only detectable in small molecule-treated culture after D14 28,29,32 or in spheroids33. In contrast, the mRNA expression did not appear to be translated into function in the case of CYP2C8 and CYP2C19, as their activity declined during culturing, even in SPHH-5C cultures, where the highest activity was observed (Table 2). In a previous paper, the metabolic activity of CYP2C8 was reported to be detectable in spheroid culture and not in SPHH33.

Our results revealed overexpression of CYP3A4 and CYP1A2 mRNA compared to the cell suspension in SPHH-5C cultures, while in PHH cells basal expression level was reported with 5C treatment29,32. At the same time, hepatocytes treated with other small molecule cocktail or cultured in spheroids showed overexpression of these enzymes28,33. In SPHH-5C cultures metabolic activity of CYP3A4 and CYP1A2 was not in line with their mRNA overexpression, since the cells maintained their basal activity level. CYP3A4 and CYP1A2 function was reported to be maintained or at least detectable in PHH culture treated with small molecules or in spheroids28,29,32. Additionally, Bell et al. reported that metabolism by CYP3A4 and CYP1A2 in spheroids was at least 2–3 folds higher than in SPHH cultures33. Our findings suggest that 2D cultures with the improved methods, in addition to the reported spheroid models, may provide stable cultures and reliable CYP evaluation, in line with the conclusion of Zhong et al.32

The mRNA level of OATP1B1, MDR3, NTCP, OCT1, BSEP and OAT2 markedly decreased - similarly to that of CYP enzymes - on D0 compared to their expression in hepatocyte suspension, while BCRP, MRP2 and MDR1 mRNA was highly overexpressed during culturing. Previously, the overexpression of BCRP and MRP2 was also described in 5C-treated cultures29,32. In contrast to metabolic enzymes, all transporters except OAT2 were recovered under all culture conditions. The stability of biliary efflux transporter expression on D0 is likely to serve as a protective mechanism during the phases of attachment, recovery, and in vitro culturing of hepatocytes, facilitating the elimination of harmful compounds and metabolites. On the contrary, the decrease in uptake transporter expression prevents cells from being overloaded with unnecessary compounds during the highly delicate attachment period34,35.

OATP1B1, MDR3, NTCP and OCT1 mRNA expressions regained their original values by D7 in SPHH-5C and SPHH, while BSEP level was only recovered in 5C treated cultures. In agreement with our data, OATP1B1 and OCT1 gene expression was described to be similar between PHH-5C, SPHH and 3D cultures, and also BSEP mRNA abundance was best maintained in PHH-5C even compared to spheroids32. Also, NTCP expression was preserved in PHH-5C for 60 days29. In contrast, others reported an elevated OCT1 level in spheroids compared to SPHH, while BSEP mRNA level was the same in both cultures33,36. The expression of MDR1 and OATP1B1 was not sustained in spheroid cultures33. As these transporters are important in ADME-Tox processes the small molecule-treated 2D models may provide better IVIV predictions compared to the spheroids in this regard.

For CYP function characterization, substrate cocktails are commonly used33. Here, we developed a method for measuring the activity of the most relevant hepatic drug uptake transporters (OATP1Bs, NTCP, OAT2, OCT1) using their specific substrates in cocktail. Previously, different substrate cocktails for the measurement of transporter functions has been described37,38. In those studies, uptake and efflux transporters were investigated simultaneously, and some significant uptake transporters were not incorporated.

The uptake clearance results showed good correlation with the gene expression data. The uptake of rosuvastatin, GCDC and sumatriptan was highest in the presence of 5C on D21, although, activity was maintained in SPHH culture as well. Consistent with mRNA levels, ketoprofen uptake clearance via OAT2 was the highest in SPHH cultures, but, as opposed to other transporters, 5C treatment has no advantageous effect on OAT2 activity.

Bile canaliculi structures were also investigated across the three culture conditions using fluorescent substrates of biliary efflux transporters. In PHH-5C bile canaliculi were present on D21, in agreement with previous studies, where PHH cultures treated with either 5C or YPAC retained their polygonal morphology for up to 30 days28, and functional bile pockets were also shown29. However, in our system, sandwich configuration combined with 5C treatment resulted in better maintenance of functional biliary pockets compared to PHH-5C. Functional bile canaliculi and efflux transporter systems are important for long-term toxicological assessment as it was supported by Chen et al. They described similar TC50 values for a set of compounds measured at Day 28 in hepatocytes treated with a small molecule cocktail as in freshly seeded hepatocyte culture27.

Historically, results concerning Phase I enzyme and hepatobiliary transporter expressions and functions have been controversial, due to different experimental setups, and lot-to-lot variabilities, among others. Compared to CYP enzymes, activity of transporters is affected by a multitude of additional mechanisms (e.g. trafficking, membrane externalization, internalization) highlighting the need for functional characterization of hepatobiliary transporters, however, available data is limited. Here, we not only provide relevant data for the function of hepatic uptake transporters, but also developed a novel, high-throughput method for the measurement of hepatic uptake and efflux.

We demonstrate for several CYP enzymes and transporters that the expression levels and the corresponding hepatic functions do not follow the same trend during culturing. In agreement, others found that the mRNA levels and the protein abundance do not necessarily correlate36,39,40, even in 5C cultures32. Here, we did not measure protein abundance, instead, more relevant functional measurements were performed to provide data for actual activity of hepatobiliary transporters and CYP enzymes.

Long-term hepatocyte cultures are usually prepared from single-donor lots27,29. To correct for inter-individual variances parallel experiments are routinely conducted using hepatocytes from different donors, however, this approach robustly increases the costs, labor and time consumption. Along these lines, we performed our experiments with a multi-donor hepatocyte lot as well. Despite the differences in the overall activity and expression of hepatic transporters and CYP enzymes of the tested lots, the effect of culture conditions on hepatic functions were similar. Here we show for the first time the utility of multi-donor lots for long-term culturing.

Our results provide evidence that 5C treatment extends hepatic functions of sandwich cultured primary hepatocytes. Due to inhibition of EMT by 5C (see mechanistic insights in introduction) proper cell polarization made available by the sandwich configuration, hepatic functions (e.g. albumin and urea secretion) together with metabolic enzyme and transporter expression are better maintained. Similar advantages have been reported by culturing hepatocytes in spheroid configuration10,33. Both models have pros and cons. Therefore, it would be informative to make side-by side comparisons of 2D-5C and 3D culturing methods and determine their best application. For transporter assays, 2D-5C cultures are more applicable and reliable, since current spheroid methodologies fail to support uptake and efflux clearance measurements39. On the other hand, SPHH-5C cultures require regular medium replacement, which technically limits their applicability for metabolic stability measurements of slow clearance compounds. However, both 2D-5C and 3D cultures could be applied to determine the hepatotoxic potential of drug candidates in preclinical tests.

In this study, we demonstrate the long-term advantage of 5C treatment of sandwich-cultured hepatocytes by gene expression, metabolic activity, dynamic uptake clearance, and the functionality of bile pockets. We show that major CYP isoforms (including CYP2C8, CYP2C9, CYP2B6, CYP3A4, CYP1A2, CYP2D6, and CYP2C19) and hepatic transporters (MDR1, MDR3, MRP2, BSEP, BCRP, NTCP, OCT1, and OATP1B1) were maintained up to 21 days, with the sole exception being OAT2. By applying a novel substrate mix in uptake clearance measurements, the number of hepatocytes required for comprehensive studies is dramatically reduced, making it suitable for high-throughput studies. As a conclusion, we provide a robust, highly reliable method for long-term maintenance of hepatic functions.

Future perspectives

The polarization of human hepatocytes and stabilization of cultures takes at least 5–7 days, that is why DILI measurements are usually started on the 5th or 7th day after seeding8,23,25,27,33. Our data support that the activity of all CYP enzymes, with the exception of CYP3A4, do not change significantly between Day 7–21, which enables conducting toxicity and DDI experiments for at least two weeks. In a preliminary experiment, hepatocytes were successfully maintained for 4 weeks, opening up the possibility of further expansion of the culture time of hepatocytes. As the health effects of chronic toxicity can vary depending on the drug, dosage, and duration of exposure, our model might be applied for chronic DILI prediction.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Plateable cryopreserved human hepatocytes were purchased from BioreclamationIVT (Westbury, NY) [lot: IRZ (F00995-P), UDT (X008001-P), XRC, HSH (X008052-P)] and from Preci (Kyiv, Ukraine) (lot: HEP187721). The cells were seeded on collagen type-I (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) coated plates in Null medium (Williams’ Medium E (Sigma-Aldrich), 100x GlutaMAX (Gibco, Billings, MT), 100x Penicillin-Streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS (Gibco), 100x Insulin-Transferrin-Selenium (ITS, Gibco) and 1 µM dexamethasone (D1756, Merck)). 50,000 cell/well were seeded on 96-well TC PhenoPlate (Revvity, Waltham, MA) and 200,000 cell/well on 48-well advanced TC plates (Greiner, Kremsmünster, Austria). At 24 h after seeding, SPHH and SPHH-5C cells were overlayed with 0.25 mg/ml Matrigel (Corning Inc., Corning, NY) in Null medium supplemented with ITS and 0.1 µM dexamethasone for SPHH and in Null medium supplemented with ITS and 0.1 µM dexamethasone, 50x B27 (Gibco) and 3000x RePrime-5C mix (Cellagen Technology, San Diego, CA) for SPHH-5C cultures. Matrigel overlaying was repeated every week. SPHH cells were kept in Null medium supplemented with ITS and 0.1 µM dexamethasone, while the medium for SPHH-5C and PHH-5C cells contained Null medium supplemented with ITS, 0.1 µM dexamethasone, 50x B27 and 3000x RePrime-5C mix. The medium was replaced according to Fig. 6.

Albumin and Urea secretion, and LDH release

Supernatant samples were collected according to Fig. 6. Albumin levels were measured using Human Albumin AssayMax ELISA Kit (Assaypro LLC, St. Charles, MO), and urea secretion was quantified by StanBio Urea Kit (Fisher, Waltham, MA). The release of LDH from the cells was assessed using the CyQuant LDH Cytotoxicity Assay Kit (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA). The assays were performed based on the instructions of the manufacturers, and plates were measured in CLARIOstar PLUS plate reader system (BMG LABTECH, Ortenberg, Germany). Figures were generated with GraphPad Prism 10 (GraphPad Prism Software, version 10.5, San Diego, CA, USA; URL: www.graphpad.com).

Quantitative real-time PCR (RT-qPCR)

The total RNA from SPHH, SPHH-5C and PHH-5C cells were collected from the cell suspension before seeding and from wells on D0 (4 h after seeding), D4, D7, D14 and D21 in triplicates using NucleoSpin RNA Extraction Kit (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA with LunaScript RT SuperMix Kit (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) according to the manufacturer’s manual. RT-qPCR was carried out using TaqMan Fast Advanced Master Mix (ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA) and performed on QuantStudio5 Real-time PCR System (ThermoFisher). The applied TaqMan probes (ThermoFisher) were the following: 18 S (Hs99999901_s1), CYP1A2 (Hs00167927_m1), CYP2B6 (Hs04183483_g1), CYP2D6 (Hs04931916_gH), CYP2C8 (Hs00426387_m1), CYP2C9 (Hs04260376_m1), CYP2C19 (Hs00426380_m1), CYP3A4 (Hs00604506_m1), OTP1B1 (Hs00272374_m1), NTCP (Hs00914890_m1), OCT1 (Hs00427552_m1), OAT2 (Hs00198527_m1), BCRP (Hs01053790_m1), BSEP (Hs00994805_m1), MRP2 (Hs00960489_m1), MDR1 (Hs01070654_g1), MDR3 (Hs00240956_m1). The results were calculated by using the ΔΔCT method against 18 S housekeeping gene and the D0 cell suspension values. The data are presented as mean. Figures were generated with GraphPad Prism 10.

Measurement of CYP enzyme activity

CYP enzyme activity was measured in the cell suspension on D0 and on D4, D7, D14 and D21 in SPHH, SPHH-5C, and PHH-5C cells using reference substrates. The reference substrates for CYP enzymes were divided in two cocktails, based on their specificity and the validation of the analytical methods utilized. The applied substrate concentrations are listed in Supplementary Table S1. First, Cocktail 1 was added to the cells in HBSS, and following 45-min the supernatant was collected. Then Cocktail 2 was introduced to the cells for another 45 min and then the supernatants were collected for metabolite quantification. The metabolites in the supernatant were analyzed by LC-MS/MS. Analysis of the compounds listed in Supplementary Table S1 was performed on an LS-I autosampler (Sound Analytics, Niantic, CT) equipped with Agilent 1260 HPLC pumps coupled to a Sciex 6500 + Triple Quadrupole Mass Spectrometer (AB SCIEX, Framingham, MA). Chromatographic separation was achieved on a Phenomenex Kinetex F5Column (30 × 2.1 mm, 2.6 μm, Phenomenex Inc., Torrance, CA) at 55 °C with a gradient elution described in Supplementary Table S2. Separation of analytes was achieved in 1.6 min in total. Eluent A consisted of 0.1% formic acid and 1 mM ammonium fluoride in water, eluent B consisted of 0.1% formic acid and 1 mM ammonium fluoride in acetonitrile. Calibration and QC samples were prepared by serial dilution (x/3) of a pooled working solution of 1000 nM of the analytes. Stabil isotope labeled internal standards were used for the quantification of analytes (acetaminophen-D4, desethylamodiaquine-D5, dextrorphan-D3, OH-bupropion-D6, OH-mephenytoin-D3, OH-midazolam-D5 and OH-tolbutamide-D9, respectively). Pooled internal standard working solution was added at a concentration of 50 nM to both unknown and calibration samples prior to analysis. 2 µl samples were injected into the HPLC-MS/MS system. Mass spectrometric detection was performed in MRM mode, and the parameters for each analyte were optimized during method development. Protein quantification was carried out with the BCA Reagent Protein Kit (Sigma). Figures were generated with GraphPad Prism 10.

Measurement of transporter activity

In preliminary experiments, selective substrate for each uptake transporter (OATPs, NTCP, OAT2 and OCT1) was studied to find compounds suitable for measuring uptake transport using them in cocktail. PHH cells were treated with 1 µM rosuvastatin (FR27760, Biosynth, Staad, Switzerland), sumatriptan (S1198, Sigma), ketoconazole (K1003, Sigma) and glycochenodeoxycholic acid (GCDC, G0759, Merck, Rahway, NJ) in HBSS, separately, and in mixture for 2 min at 37 °C. Passive uptake was evaluated applying a 4-component inhibitor cocktail containing 20 µM rifamycin SV (R8626, Merck), 50 µM troglitazone (T2573, Sigma), 50 µM verapamil (V4629, Sigma) and 100 µM indomethacin (I7378, Merck). For analytical sampling purposes, cells were extracted with MeOH: HBSS 2:1, and substrate concentrations were analyzed using LC-MS/MS. Following successful validation of the method, uptake activity of SPHH, SPHH-5C, and PHH-5C cells were measured applying the 4-component substrate mixture. On D0, D4, D7, D14 and D21 the cells received the substrate mixture with and without inhibitor cocktail, and the compounds in the lysed cells were evaluated by LC-MS/MS. Analysis of glycochenodeoxycholic acid (GCDC), ketoprofen, rosuvastatin and sumatriptan was performed on an Agilent 1290 HPLC coupled to and Agilent 6470 A Triple Quadrupole Mass Spectrometer (Agilent Technologies Inc., Santa Clara, CA). Chromatographic separation of GCDC and ketoprofen was achieved on a Phenomenex Kinetex EVO column (20 × 2.1 mm, 2.6 μm, Phenomenex Inc.) at 40 °C with a gradient elution in Supplementary Table S3. Eluent A consisted of 0.2% formic acid in water, eluent B consisted of 0.2% formic acid in acetonitrile. Chromatographic separation of rosuvastatin and sumatriptan was achieved on a Phenomenex Kinetex F5Column (50 × 2.1 mm, 2.6 μm, Phenomenex Inc.) at 40 °C with a gradient elution in Supplementary Table S4. 95% B content was then held for 0.45 min to wash the column, then at 1.90 min eluent composition was changed back to 1% B, then a re-equilibration of the column was performed in 0.1 min. Eluent A consisted of 0.1% formic acid in water, eluent B consisted of 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile. Calibration and QC samples were prepared by serial dilution (x/3) of a 2000 nM pooled working solution of the analytes. 8 µl of GCDC, ketoprofen samples and 2 µl of rosuvastatin and sumatriptan samples were injected into the HPLC-MS/MS system. Mass spectrometric detection was performed in MRM mode, and parameters for each analyte were optimized during method development. Protein quantification was carried out with the BCA Reagent Protein Kit (Sigma). Figures were generated with GraphPad Prism 10.

Fluorescent imaging

For visualization of the bile pockets SPHH, SPHH-5C and PHH-5C cells were incubated with CDCF-DA, which is a non-fluorescent compound that enters the cells passively, and after the cleavage of the acetate groups the fluorescent CDCF is eliminated into the bile pockets via MRP2. MK-571 was applied as a well-known MRP2 inhibitor to prove that CDCF is transported actively into the bile canaliculi via this transporter. Cells were incubated with 30 µM MK-571 (M7571, Merck), for 30 min followed by the addition of 2 µM CDCF-DA (21882, Sigma), and 5 µg/ml Hoechst 33342 (62249, Thermo Scientific) for 10 min in HBSS.

To assess the function of NTCP and BSEP transporters, a shared substrate, tauronor (synthetized by BioBlocks, San Diego, CA), was also tested. Cells were incubated with 20 µM tauronor and 5 µg/ml Hoechst 33342 followed by an efflux period, with or without 10 µM cyclosporin A (30024, Sigma), a potent BSEP inhibitor, for 30 min in HBSS. The fluorescent imaging was done by Revvity Opera Phenix Plus High Content Imaging Instrument with a 20x objective for CDCF (Ex: 488, Em: 500–550) and a 63x water immersion objective for tauronor (Ex: 488, Em: 500–550). Cell count was determined based on the Hoechst channel (Ex: 405, Em: 435–480). For data analyzes Revvity Harmony software was used. Figures were generated with GraphPad Prism 10.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyzes were performed using GraphPad Prism 10 (GraphPad Prism Software, version 10.5, San Diego, CA, USA; URL: www.graphpad.com) with data from triplicate experiments (n = 3) presented as mean ± SD. Two-way ANOVA was applied to evaluate the effects of culture condition and time on measured parameters. Post-hoc analyzes used Dunnett’s test for comparisons against Day 0 control (or initial cell suspension) to assess functional preservation over time relative to the initial state. Tukey’s test was employed for all pairwise comparisons between groups at each timepoint, enabling us to identify optimal culture conditions. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available, but available upon request from the corresponding author.

References

Fernandez-Checa, J. C. et al. Advanced preclinical models for evaluation of drug-induced liver injury - consensus statement by the European Drug-Induced liver injury network [PRO-EURO-DILI-NET]. J. Hepatol. 75, 935–959 (2021).

Kuna, L. et al. Models of drug induced liver injury (DILI) – Current issues and future perspectives. Curr. Drug Metab. 19, 830–838 (2018).

Susukida, T., Sekine, S., Nozaki, M., Tokizono, M. & Ito, K. Prediction of the clinical risk of Drug-Induced cholestatic liver injury using an in vitro sandwich cultured hepatocyte assay. Drug Metab. Dispos. 43, 1760–1768 (2015).

Bonn, B., Svanberg, P., Janefeldt, A., Hultman, I. & Grime, K. Determination of human hepatocyte intrinsic clearance for slowly metabolized compounds: comparison of a primary hepatocyte/Stromal cell Co-culture with plated primary hepatocytes and HepaRG. Drug Metab. Dispos. 44, 527–533 (2016).

Macko, P., Palosaari, T. & Whelan, M. Extrapolating from acute to chronic toxicity in vitro. Toxicol. Vitro. 76, 105206 (2021).

McKim, J. Jr Building a tiered approach to in vitro predictive toxicity screening: A focus on assays with in vivo relevance. Comb. Chem. High. Throughput Screen. 13, 188–206 (2010).

Wilkening, S. & Bader, A. Influence of culture time on the expression of drug-metabolizing enzymes in primary human hepatocytes and hepatoma cell line HepG2. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 17, 207–213 (2003).

Bell, C. C. et al. Characterization of primary human hepatocyte spheroids as a model system for drug-induced liver injury, liver function and disease. Sci. Rep. 6, 25187 (2016).

Hu, H. et al. Long-Term expansion of functional mouse and human hepatocytes as 3D organoids. Cell 175, 1591–1606e19 (2018).

Riede, J., Wollmann, B. M., Molden, E. & Ingelman-Sundberg, M. Primary human hepatocyte spheroids as an in vitro tool for investigating drug compounds with low hepatic clearance. Drug Metab. Dispos. 49, 501–508 (2021).

Ueyama-Toba, Y. et al. Development of a hepatic differentiation method in 2D culture from primary human hepatocyte-derived organoids for pharmaceutical research. iScience 27, 110778 (2024).

Bale, S. S. et al. Long-Term coculture strategies for primary hepatocytes and liver sinusoidal endothelial cells. Tissue Eng. Part. C Methods. 21, 413–422 (2015).

Katsuda, T. et al. Generation of human hepatic progenitor cells with regenerative and metabolic capacities from primary hepatocytes. eLife 8, e47313 (2019).

Jellali, R. et al. Long-term human primary hepatocyte cultures in a microfluidic liver biochip show maintenance of mRNA levels and higher drug metabolism compared with petri cultures. Biopharm. Drug Dispos. 37, 264–275 (2016).

Byeon, J. H., Jung, D. J., Han, H. J., Son, W. C. & Jeong, G. S. Fast formation and maturation enhancement of human liver organoids using a liver-organoid-on-a-chip. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 12, 1452485 (2024).

Kaur, I. et al. Primary hepatocyte isolation and cultures: technical Aspects, challenges and advancements. Bioengineering 10, 131 (2023).

Mun, S. J. et al. Long-Term expansion of functional human pluripotent stem Cell-Derived hepatic organoids. Int. J. Stem Cells. 13, 279–286 (2020).

Shinohara, M. et al. Coculture with hiPS-derived intestinal cells enhanced human hepatocyte functions in a pneumatic-pressure-driven two-organ microphysiological system. Sci. Rep. 11, 5437 (2021).

Shoemaker, J. T. et al. A 3D cell culture Organ-on-a-Chip platform with a breathable hemoglobin analogue augments and extends primary human hepatocyte functions in vitro. Front. Mol. Biosci. 7, 568777 (2020).

Hu, Y. et al. Research progress and application of liver organoids for disease modeling and regenerative therapy. J. Mol. Med. 102, 859–874 (2024).

Sugahara, G. et al. Long-term cell fate and functional maintenance of human hepatocyte through Stepwise culture configuration. FASEB J 37, (2023).

Handin, N. et al. Conditions for maintenance of hepatocyte differentiation and function in 3D cultures. iScience 24, 103235 (2021).

Horiuchi, S. et al. Formation of functional, extended bile canaliculi, and increased bile acid production in sandwich-cultured human cryopreserved hepatocytes using commercially available culture medium. Arch. Toxicol. 98, 2605–2617 (2024).

Liu, Y. et al. Generation and characterization of mature hepatocyte organoids for liver metabolic studies. J. Cell. Sci. 137, jcs261961 (2024).

Meneses-Lorente, G. et al. Utility of Long-Term cultured human hepatocytes as an in vitro model for cytochrome P450 induction. Drug Metab. Dispos. 35, 215–220 (2007).

Tong, Y. et al. Efficient hepatocyte differentiation of primary human hepatocyte-derived organoids using three dimensional nanofibers (HYDROX) and their possible application in hepatotoxicity research. Sci. Rep. Nat. Publ Group. 14, 10846 (2024).

Chen, Y. et al. Assessment of long-term functional maintenance of primary human hepatocytes to predict drug-induced hepatoxicity in vitro. Arch. Toxicol. 95, 2431–2442 (2021).

Katsuda, T. et al. Long-term maintenance of functional primary human hepatocytes using small molecules. FEBS Lett. 594, 114–125 (2019).

Xiang, C. et al. Long-term functional maintenance of primary human hepatocytes in vitro. Science 364, 399–402 (2019).

Cicchini, C. et al. Molecular mechanisms controlling the phenotype and the EMT / MET dynamics of hepatocyte. Liver Int. 35, 302–310 (2015).

LeCluyse, E. L. Human hepatocyte culture systems for the in vitro evaluation of cytochrome P450 expression and regulation. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 13, 343–368 (2001).

Zhong, Y., Yu, J. S., Wang, X., Binas, B. & Yoo, H. H. Chemical-based primary human hepatocyte monolayer culture for the study of drug metabolism and hepatotoxicity: comparison with the spheroid model. FASEB J 35, (2021).

Bell, C. C. et al. Comparison of hepatic 2D sandwich cultures and 3D spheroids for Long-term toxicity applications: A multicenter study. Toxicol. Sci. 162, 655–666 (2018).

Jigorel, E., Le Vee, M., Boursier-Neyret, C., Parmentier, Y. & Fardel, O. Differential regulation of sinusoidal and canalicular hepatic drug transporter expression by xenobiotics activating drug-Sensing receptors in primary human hepatocytes. Drug Metab. Dispos. 34, 1756–1763 (2006).

Luttringer, O. et al. Influence of isolation procedure, extracellular matrix and dexamethasone on the regulation of membrane transporters gene expression in rat hepatocytes. Biochem Pharmacol. 1637–1650 (2002).

Mickols, E. et al. OCT1 (SLC22A1) transporter kinetics and regulation in primary human hepatocyte 3D spheroids. Sci. Rep. Nat. Publ Group. 14, 17334 (2024).

Ebner, T., Ishiguro, N. & Taub, M. E. The use of transporter probe drug cocktails for the assessment of transporter-Based drug–Drug interactions in a clinical Setting—Proposal of a four component transporter cocktail. J. Pharm. Sci. 104, 3220–3228 (2015).

Guo, C., Brouwer, K. L. R., Brouwer, K. R., Stewart, P. W. & Mosley, C. Probe cocktail to assess transporter function in Sandwich-Cultured human hepatocytes. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 22, 567–575 (2019).

Järvinen, E., Hammer, H. S., Pötz, O., Ingelman-Sundberg, M. & Stage, T. B. 3D spheroid primary human hepatocytes for prediction of cytochrome P450 and drug transporter induction. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 113, 1284–1294 (2023).

Wegler, C. et al. Global variability analysis of mRNA and protein concentrations across and within human tissues. NAR Genomics Bioinforma. 2, lqz010 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the 2024-2.1.2-EKÖP-KDP new National Excellence Program of the Ministry for Culture and Innovation from the source of the National Research, Development an Innovation Fund and was executed at Charles River Laboratories Hungary. Special thanks to Gábor Nagy for his help in reviewing and revising the manuscript and to Nóra Szilvásy for her help with statistical analyzes.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JP, data collection and analyzes, manuscript writing. NB, data collection and analyzes, manuscript review. KK and OCs, analytical measurements and analyzes. KJ, BMT and ZsG, study design, data interpretation and manuscript review. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Charles River Laboratories Hungary, as the employer of all the authors, develops and commercializes assays to study hepatotoxicity and hepatic metabolism. The authors declare no other conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pacsuta, J., Bárány, N., Kiszelák, K. et al. Expression and function of CYP enzymes and hepatobiliary transporters in an improved long-term sandwich culture hepatocyte model. Sci Rep 16, 3380 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33332-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33332-9