Abstract

Driven by the concepts of digital twin and metaverse, constructing a high-fidelity, semantic-rich, and interactive digital copy of the physical world has become a key issue in the field of surveying, mapping, and geographic information. However, in typical complex landforms such as urban canyons and mountainous forest areas, the single-sensor data acquisition methods (such as UAV oblique images and lidar) has inherent information blind spots and accuracy bottlenecks. Traditional data fusion approaches predominantly focus on shallow geometric alignment and splicing at the geometric level, ignoring the heterogeneity of different data sources in semantic connotations, leads to common problems such as geometric distortion, detail loss, and semantic inconsistency in the fusion products. To break through this dilemma, this paper proposes an adaptive fusion framework for multi-source data of complex landforms (SAAF-Net) with deeply coupled semantic information. Centered on computer vision, this framework constructs a full-link technical process from raw data to high-precision semantic 3D models: Two-stream parallel semantic parsing: A two-stream deep semantic segmentation network for images and point clouds (based on SegFormer and PointNeXt) is designed to achieve fine-grained classification of scene features (the average intersection over union mIoU exceeds 90%), providing high-dimensional semantic priors for fusion. Semantic-guided cross-source registration: A semantic weighted iterative closest point algorithm (SW-ICP) is proposed. By constraining the corresponding point search space through cross-source semantic consistency and combining with the significance weighting of local geometric structures, the robustness problem of heterogeneous data registration is solved. Neural adaptive fusion modeling: A multi-factor driven neural network model is constructed to dynamically evaluate the confidence of data sources under different semantic categories and observation conditions, achieving the optimal fusion of pixel-level elevation and texture. Experiments in the city center and mountainous forest areas show that compared with mainstream methods, the root mean square error (RMSE) of SAAF-Net is reduced by 35% − 48%, and the completeness is improved to over 99%. Especially, the reconstruction quality in building edges, vegetation-covered areas, and light-shadow areas is significantly improved.with a substantial enhancement in visual realism. This research provides theoretical and technical support for the construction of a high-precision 3D base for digital twin cities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Research background and significance

The world is accelerating into a new era characterized by digitalization, networking, and intelligence. As a real-time mapping and interaction paradigm between the physical world and the cyber space, digital twin has become the core technological engine driving major national strategic needs such as smart cities1, dynamic monitoring of natural resources2, disaster emergency simulation3, and carbon neutrality assessment4. Building a high-precision, high-fidelity, and semantically rich three-dimensional geospatial model is the fundamental digital foundation for realizing digital twin. This high-precision three-dimensional model is not only a carrier of spatial information but also a comprehensive platform that bears physical attributes, social functions, and management information. It can support innovative applications in many fields such as urban planning, infrastructure management, environmental protection, emergency response, cultural heritage protection, and even virtual reality and augmented reality. Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) oblique photography and Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) technologies have become the mainstream technical means for building this digital foundation due to their efficient and flexible data acquisition capabilities5. However, to achieve a comprehensive and accurate replication of the physical world in the digital world and support in-depth analysis and simulation, unprecedented requirements are put forward for the accuracy, completeness, and semantic richness of the three-dimensional model.

The inherent duality and limitations of mainstream technologies

Although UAV oblique photography and LiDAR technologies are widely used, there is a fundamental dual contradictions in their data acquisition mechanisms, which determines their respective inevitable limitations.

UAV oblique photography: The “photometric - geometric” dilemma of passive imaging. In essence, this technology infers the geometric structure of the scene through the photometric consistency of multi - view images. Its core algorithms, Structure from Motion (SfM) and Multi - View Stereo (MVS), heavily rely on robust feature point matching and pixel - level color discrimination6. However, in complex terrains, this dependence becomes extremely fragile. For example, in the deep shadow areas of urban canyons, insufficient illumination leads to blurred or missing image textures; on highly reflective surfaces such as glass curtain walls, smooth metal roofs, or water bodies, the complex light reflection characteristics are prone to produce wrong matching points or sparse feature points; in large - area single - tone walls, repetitive textures (such as dense windows), or dynamic scenes (such as moving vehicles and swaying trees), the ambiguity or instability of feature matching will increase significantly. All these situations may cause the Cost Computation and Cost Aggregation steps of the MVS algorithm to fail, leads to model holes, geometric distortion, and false “texture replication” artifacts, which seriously affect the integrity and accuracy of the three - dimensional model7.

LiDAR Scanning: The “Geometry-Semantics” Gap in Active Measurement. LiDAR technology directly obtains high-precision three-dimensional coordinates by actively emitting lasers and measuring the echo time. It has extremely high geometric fidelity and is not affected by illumination. It can effectively penetrate vegetation to obtain the real surface terrain (DTM)8. This active measurement method gives LiDAR unique advantages in harsh lighting conditions, textureless areas, and vegetation-covered areas. However, its advantages also bring new problems. First, LiDAR point clouds are essentially discrete geometric samplings, lacking continuous surface information and real color textures, and thus difficult to meet the requirements of digital twins for visual realism9. What users see is only a sparse geometric skeleton composed of points, rather than a realistic digital scene. Second, the high equipment cost and low operation efficiency (especially for ground LiDAR scanning of large-scale areas) limit its large-scale and rapid application. Most importantly, the original LiDAR point clouds only contain geometric information (X, Y, Z, Intensity), and there is a huge “geometry-semantics” gap. That is, we know “there is a point here”, but we don’t know “what this point belongs to”10. The lack of such semantic information seriously hinders the ability of downstream applications to conduct intelligent analysis, attribute association, and decision support for models.

Dilemma of data fusion: core scientific challenges

To achieve complementary advantages, fusing UAV images and LiDAR point clouds has become an inevitable choice11. However, simple data superposition cannot solve the problem and may even introduce new contradictions. Current fusion technologies face two core scientific challenges:

Challenge of Robust Registration of Cross-Modal Heterogeneous Data: There are huge differences between UAV-SfM point clouds and LiDAR point clouds in terms of data sources, acquisition mechanisms, densities, error distributions, noise patterns, and data forms. UAV-SfM point clouds usually have uneven densities and low accuracy in textureless areas, while LiDAR point clouds have uniform densities but may have systematic errors and scanning blind spots. Traditional registration methods based on geometric features (such as FPFH12 have a high failure rate due to the lack of consistency in feature descriptions under different modalities. For example, the point clouds generated from images may not have enough feature points on flat roofs, while LiDAR point clouds may have local missing parts due to scanning angle problems. The ICP algorithm15 and its variants have non-convex optimization objectives, have a large number of local minima in complex scenarios, are extremely sensitive to the initial pose, and are prone to converge to wrong results, leads to “double images” or misalignment in the fusion model. In recent years, although there have been some progresses in registration methods based on deep learning13,14, their generalization ability and processing efficiency for large-scale scenarios are still bottlenecks, making it difficult to directly apply them to actual surveying and mapping projects.

Intelligent fusion challenges considering semantic optimality: Traditional fusion strategies, whether the simple mean/median method16 or the weighting method based on geometric quality17, are essentially “geometry-driven”. They cannot answer a fundamental question: “For a specific feature, which data source is more reliable?” For example, on building roofs, the SfM model may be superior due to its rich details and can capture fine structures such as chimneys and skylights. However, under the eaves or in shadow areas, the SfM model may have holes or geometric distortions. Meanwhile, LiDAR is irreplaceable under vegetation as it can penetrate the canopy to obtain the true ground elevation. Fusion that ignores semantics will inevitably lead to the offset rather than complementarity of information advantages. For example, simply averaging the ground points under the forest of LiDAR and the canopy surface points of UAV will result in an unrealistic “mid-air” elevation, and the final model quality will be mediocre, even worse than that of a single data source. How to intelligently identify the advantages and disadvantages of different data sources for different semantic features and conduct adaptive fusion accordingly is the most core scientific challenge in the current field of multi-source data fusion. Fusion that ignores semantics will inevitably lead to the offset rather than complementarity of information advantages, and the final model quality will be mediocre, even worse than that of a single data source.

Contributions of this paper

To address the above challenges, this paper proposes a Semantic-Aware Adaptive Fusion Network (SAAF-Net). We advocate that semantic information is the key to bridging the gap between multi-source data and achieving a leap from “data splicing” to “knowledge fusion”. The core innovations of this paper are as follows:

Semantic-driven registration paradigm: The SW-ICP algorithm is innovatively proposed, which takes cross-source semantic consistency as the core driving force for registration optimization. By strictly restricting semantic categories in the corresponding point search stage and dynamically weighting in combination with the saliency of local geometric structures, the objective function of the optimization problem is reshaped, significantly improving the registration robustness and accuracy in complex scenarios and effectively avoiding the problem that traditional methods are prone to fall into local optima for heterogeneous data.

Learnable optimal fusion strategy: A multi-factor adaptive fusion model driven by a small neural network is designed to enable it to automatically learn the optimal fusion weights from the data, replacing the traditional fusion methods that rely on manual experience rules. This network can flexibly adjust the contributions of different data sources according to the different semantic categories, data quality features, and geometric consistency features of pixels/points, ensuring that the most reliable information is selected for fusion in any local area.

Integrated Full-Process Solution: A complete and highly automated technical pipeline is proposed, clearly defining the entire workflow from raw data to the final product. It covers key stages including data preprocessing, dual-stream high-fidelity semantic parsing, semantic-guided fine registration, neural adaptive fusion modeling, and high-fidelity texture mapping. This framework is not only an innovative theoretical model but also a practical system that can significantly reduce manual intervention, improve the efficiency of surveying and mapping production, and provide a high-performance solution for industry applications.

Basic theory and problem formalization

An information theory perspective on data fusion

From the perspective of information theory, the essence of multi-source data fusion is a process of information purification and enhancement18. It aims to extract the most reliable and comprehensive information from multiple imperfect, noisy but complementary data sources to construct a closer perception of the real world. Assume that the real world is \(\:W\), the UAV image data source is \(\:{S}_{img}\), the LiDAR data source is \(\:{S}_{lidar}\), and the fused model is \(\:M\). The ideal fusion goal is to maximize the mutual information \(\:I\left(M;W\right)\) between the fused model \(\:M\) and the real world, while minimizing the redundant information and noise in \(\:M\).

Among them, \(\:H\left(M\right)\) is the information entropy of, and \(\:H\left(M\mid\:W\right)\) is the uncertainty (noise) of \(\:M\) under the condition of knowing the real world \(\:W\). \(\:{S}_{img}\) and \(\:{S}_{lidar}\) are two imperfect and noisy observations of \(\:W\). \(\:{S}_{img}\) has high mutual information with \(\:W\) in texture information, but has high uncertainty in geometric information in some areas; \(\:{S}_{\text{lidar}}\) has high mutual information with \(\:W\) in geometric information, but lacks semantic and texture information. A successful fusion strategy should be able to adaptively extract the parts with the highest mutual information with \(\:W\) from \(\:{S}_{img}\) and \(\:{S}_{lidar}\) and suppress the parts with high uncertainty, so that the final \(\:I\left(M;W\right)>I\left({S}_{img};W\right)\) and \(\:I\left(M;W\right)>I\left({S}_{\text{lidar}};W\right)\). This process can be understood as reducing the entropy (uncertainty) of the state estimation of the real world by introducing multi - perspective and multi - modal observations, thereby improving the purity and value of information.

Geometric and semantic inconsistency problem

The core obstacle in the fusion process is the inherent inconsistency among data sources, which makes simple data superposition ineffective. It is mainly reflected in two aspects19: Geometric inconsistency: This refers to the deviation between \(\:{S}_{\text{img}}\) and \(\:{S}_{\text{lidar}}\) in the spatial coordinate system. Even after rough georeferencing, due to factors such as internal parameter errors of sensors, atmospheric refraction (especially as the scene scale increases), and cumulative errors of SfM, there still exists a complex and non - linear spatial transformation relationship between the two. This deviation may manifest as an overall translation, rotation, or local non - rigid deformation. For example, at the building edges, the SfM model may have edge blurring or misalignment due to changes in lighting, while LiDAR may cause the edges to be “thickened” due to laser beam divergence. If these minor geometric inconsistencies are not precisely aligned, it will lead to “ghosting” and “double - edge” effects in the fused model, seriously affecting the visual quality and measurement accuracy of the model. In a local area, this transformation can be approximated as a rigid body transformation (rotation R and translation t), that is, the registration problem.

Semantic inconsistency: This means that even after geometric alignment, there may still be semantic conflicts in the representation of the same feature by the two data sources. This inconsistency stems from the differences in the imaging principles of the two sensors. For example, the model generated from UAV images may regard the surface of a dense tree canopy as the “ground” because light cannot penetrate the canopy, and the camera can only see its top and constructs a geometric model accordingly. However, LiDAR can penetrate the canopy and record the real ground points below. At this time, the elevation values of the two data at the same (x, y) position represent completely different semantic objects (tree canopy vs. ground). Similarly, the SfM model may generate distorted or missing geometry in the glass curtain wall area due to reflection or transparency, while LiDAR may obtain a relatively flat facade. Traditional fusion methods cannot recognize such semantic conflicts. They only focus on the “nearest point” or “average value” geometrically, leads to incorrect fusion results. Generating an “intermediate elevation” that is neither the tree canopy nor the ground, or a “blurred facade” that is neither distorted nor flat, makes the fused model semantically inaccurate and difficult to use for subsequent intelligent analysis.

Problem formalization

Based on the above analysis, we formalize the multi - source data fusion problem under complex landforms as a multi - objective joint optimization problem. Let the input be the UAV image set \(\:\mathcal{I}=\left\{{I}_{k}\right\}\) and the LiDAR points \(\:{P}_{L}\). The ultimate goal is to generate a high - precision, textured triangular mesh model \(\:\text{M}=\left(\text{V},\text{F},\text{T}\right)\), where \(\:\text{V}\) is the vertex set, \(\:\text{F}\) is the face element set, and \(\:\text{T}\) is the texture map. This optimization problem can be expressed as:

Among them: (R, t) are the transformation parameters from the LiDAR point cloud to the image coordinate system. \(\:{\mathcal{L}}_{\text{data}}\) is the data fidelity term, which requires the model \(\:\text{M}\) to be consistent with the aligned multi-source observation data (the SfM point cloud \(\:{\text{P}}_{\text{I}}\) and the transformed LiDAR point cloud \(\:{\text{R}\text{P}}_{\text{L}}+\text{t}\)). \(\:{\mathcal{L}}_{\text{sem}}\) is the semantic consistency term, which requires the geometric shapes and topological relationships of various objects in the model to conform to the semantic prior knowledge. \(\:{\mathcal{L}}_{\text{reg}}\) is the regularization term, which is used to ensure the smoothness and integrity of the model. \(\:{\uplambda\:}\) are the weight coefficients of each term.

The SAAF-Net proposed in this paper is exactly an effective step-by-step and modular solution framework for this complex optimization problem. By introducing semantic information as the core bridge, it collaboratively optimizes the consistency of geometry and semantics.

Technical specifications for multi-source data preprocessing

In the workflow of multi-source data fusion and analysis, data preprocessing is a fundamental and crucial step. Its processing effect directly affects the accuracy and reliability of subsequent tasks such as semantic segmentation, registration, and three-dimensional reconstruction. Data of different modalities, such as optical images acquired by unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and point cloud data collected by LiDAR, each have unique data characteristics and noise distributions. Therefore, a systematic and targeted preprocessing technical specification is needed to ensure data quality and eliminate the heterogeneity among data.

Optical image preprocessing

During the acquisition process of UAV images, they are easily interfered by various factors, leads to problems such as image distortion, uneven radiation, and the influence of dynamic objects. A series of preprocessing operations are required to improve the image quality.

Lens Distortion Correction:

Principle: The camera lenses carried by UAVs often have radial and tangential distortions, causing deviations in the geometric shapes of ground objects in the images. The Brown - Conrady model is a commonly used distortion correction model. By constructing a function containing the radial distortion coefficient \(\:{k}_{1},{k}_{2},{k}_{3}\) and the tangential distortion coefficient \(\:{p}_{1},{p}_{2}\), the pixel coordinates of the image are corrected. Let the original pixel coordinates be \(\:x,y\), and the corrected coordinates be \(\:{x}^{{\prime\:}},{y}^{{\prime\:}}\). Its cor.

rection formula is as follows:

Implementation steps: First, obtain the internal parameter matrix and distortion coefficients of the camera through the camera calibration board; then, traverse each pixel of the image, calculate the corrected coordinates according to the above formula, and fill the pixel values of the new image through methods such as bilinear interpolation to complete the distortion correction. Radiation Normalization:

Purpose: Due to differences in lighting conditions, camera exposure settings, etc., there are radiation inconsistencies in UAV images at different times or in different regions, which will affect the accuracy of subsequent semantic recognition and classification of ground objects. Radiation normalization aims to eliminate these differences and make the images have consistent radiation characteristics.

Method: The radiation normalization method based on histogram matching is commonly used. Taking the histogram of a reference image as the benchmark, other images to be normalized are processed. Let the cumulative distribution function of the reference image be \(\:{C}_{R}\left(z\right)\), and the cumulative distribution function of the image to be normalized be \(\:{C}_{T}\left(z\right)\). For the pixel value \(\:{z}_{T}\) in the image to be normalized, by finding the corresponding value \(\:{z}_{R}\) of \(\:{C}_{T}\left({z}_{T}\right)\) in \(\:{C}_{R}\left(z\right)\), \(\:{z}_{T}\) is replaced with \(\:\left({z}_{R}\right.\), thus achieving the unification of radiation characteristics.

Dynamic object removal:

Challenge: During the UAV image acquisition process, the presence of dynamic objects such as vehicles and pedestrians will interfere with the segmentation and analysis of static ground objects. Moreover, their motion states are complex, and it is difficult to remove them through simple threshold or morphological methods.

Algorithm

A dynamic object detection and removal algorithm based on the optical flow method is adopted. The optical flow method determines whether a pixel belongs to a dynamic object by calculating the motion vector of the pixel between adjacent frame images. Specifically, for each pixel point \(\:x,y\) in the image, in the adjacent frames \(\:{I}_{1}\left(x,y\right)\) and \(\:{I}_{2}\left(x,y+{\Delta\:}y\right)\), according to the brightness constancy assumption \(\:{I}_{1}\left(x,y\right)={I}_{2}\left(x,y+{\Delta\:}y\right)\), by solving the optical flow constraint equation:

Among them, \(\:u,v\) are the optical flow vectors in the \(\:x,y\) direction respectively, and the motion vector of this pixel is obtained. If the motion vector exceeds the set threshold, it is determined that this pixel belongs to a dynamic object and will be removed in subsequent processing.

Point cloud data pre - processing

LiDAR point cloud data also has problems such as noise, outliers, and uneven density during the acquisition process. It needs to undergo strict pre - processing before it can be used for subsequent modeling and analysis.

Outlier removal:

Statistical filtering: Based on the statistical characteristics of point cloud data, it is assumed that the point cloud data follows a Gaussian distribution. For each point, calculate its average distance \(\:{d}_{i}\) to neighboring points. The mean value of the average distances of all points is \(\:\mu\:\), and the standard deviation is \(\:\sigma\:\). If the \(\:{d}_{i}\) of a certain point satisfies \(\:{d}_{i}>\mu\:+k\sigma\:,k\) (where \(\:{d}_{i}>\mu\:+k\sigma\:,k\) is an empirical coefficient, usually taking a value of 2–3), then this point is determined to be an outlier and will be removed.

RANSAC plane detection: The Random Sample Consensus (RANSAC) algorithm is commonly used to detect the plane structure in the point cloud and then remove the outliers outside the plane. Its basic idea is to randomly select a set of points (usually 3 points determine a plane), through the most.

Fit the plane equation using the least squares method \(\:ax+by+cz+d=0\), then calculate the distances from other points to this plane. Points with distances less than the threshold are regarded as inliers. After multiple iterations, keep the plane model with the most inliers and remove the outliers that are not within this model.

Stratification of multi - echo LiDAR data:

Basis: After the multi - echo LiDAR system emits laser pulses, it can receive multiple reflected echoes. Different echoes correspond to ground objects at different heights. Using this characteristic, the point cloud data can be divided into different layers such as ground points, vegetation points, and building points.

Method: First, preliminarily distinguish the types of ground objects according to the echo intensity and the number of echoes. Generally speaking, the intensity of the ground - reflected echo is relatively high and mostly single - echo; the number of vegetation - reflected echoes is relatively large and the intensity is relatively weak; the intensity of the building - reflected echo is relatively high and the shape is relatively regular. Then, combined with the spatial distribution characteristics of the point cloud, further accurately divide the point cloud of each layer through methods such as constructing a triangular network or cluster analysis. For example, for the vegetation point cloud, the DBSCAN density clustering algorithm can be used to divide it into different vegetation communities according to the point cloud density.

Equalization of point cloud density:

Reason: Affected by factors such as the LiDAR scanning angle and ground object occlusion, the point cloud data has an uneven density distribution in space, which will affect the accuracy and efficiency of subsequent modeling.

Algorithm

The resampling algorithm based on the Voronoi diagram can achieve the equalization of point cloud density. First, construct the Voronoi diagram of the point cloud, and each point corresponds to a Voronoi region. Calculate the volume of each Voronoi region. If the volume of a certain region is too large (that is, the point cloud density in this region is too small), insert new points in this region according to certain rules (such as uniform distribution); if the volume of a certain region is too small (that is, the point cloud density in this region is too large), appropriately delete the points in this region, so as to make the spatial distribution of the point cloud more uniform.

Temporal and Spatial synchronization calibration

Multi - source data fusion needs to ensure the consistency of data acquired by different sensors in time and space. Temporal and spatial synchronization calibration is a key step to achieve this goal.

Timestamp alignment of multiple sensors:

Hardware trigger synchronization: For sensors such as LiDAR and cameras, a hardware trigger synchronization mechanism can be adopted. Through the synchronous pulse signal, each sensor starts data collection at the same time, so as to ensure the time consistency of the collected data. For example, use the GPS second pulse signal (1PPS) as the synchronous trigger source and connect it to the trigger interfaces of the LiDAR and the camera to ensure that both start collection at an accurate time point.

Timestamp correction: In practical applications, even if hardware trigger synchronization is adopted, due to reasons such as internal clock drift of sensors, there may still be slight deviations in the timestamps of the collected data. Therefore, it is necessary to correct the timestamps. During the collection process, the timestamps of each sensor and the time of an external high-precision clock (such as an atomic clock) can be recorded simultaneously to establish a timestamp deviation model and correct the timestamps of the collected data.

Coordinate system unification:

Principle of coordinate transformation: UAV images and LiDAR point cloud data usually adopt different coordinate systems, such as the WGS84 geographic coordinate system and the local projection coordinate system. To achieve data fusion, they need to be unified into the same coordinate system. Taking the transformation from the WGS84 coordinate system to the Gauss - Krüger projection coordinate system as an example, first, convert the longitude and latitude coordinates \(\:B,L\) into geodetic rectangular coordinates \(\:X,Y,Z\). The conversion formula is as follows:

Among them, \(\:N=\frac{a}{\sqrt{1-{e}^{2}{\text{s}\text{i}\text{n}}^{2}B}}\) is the radius of curvature of the prime vertical, \(\:a\) is the semi - major axis of the ellipsoid, \(\:e\) is the first eccentricity of the ellipsoid, and \(\:h\) is the geodetic height. Then, according to the forward calculation formula of the Gauss - Krüger projection, convert the geodetic rectangular coordinates into plane rectangular coordinates \(\:x,y\).

Analysis of transformation errors: During the coordinate transformation process, certain errors will be introduced due to factors such as the selection of ellipsoid parameters and projection deformation. To evaluate the transformation errors, coordinate transformation experiments can be carried out on known high - precision control points, the coordinate values before and after the transformation can be compared, error indicators (such as the root - mean - square error RMSE) can be calculated, the sources of errors can be analyzed, and the transformation parameters can be optimized when necessary to improve the accuracy of coordinate transformation.

SAAF-Net: semantic-aware adaptive fusion framework

Overall architecture

The overall architecture of SAAF-Net is designed for the end-to-end processing of raw multi-source data into high-precision, semantic-rich 3D models. The framework’s overall workflow is illustrated in Fig. 1. It consists of four tightly coupled modules that form an efficient pipeline from information processing to value-added products. These modules do not operate independently but are interlinked, with the output of one module providing crucial input and prior knowledge for the next, collectively enabling the high-precision 3D reconstruction of complex terrains.

Module 1: Semantic Parsing: This module is the foundation for all subsequent advanced processing. Its core task is to assign unified, high-precision pixel-level or point-level semantic labels to the two heterogeneous data sources: UAV imagery and LiDAR point clouds.

Module 2: Cross-Source Registration: Leveraging the semantic priors from Module 1, this module employs our proposed Semantic-Weighted ICP (SW-ICP) algorithm to effectively overcome the challenges of registering heterogeneous data with significant geometric and density discrepancies. This resolves the spatial geometric inconsistencies between the different data sources.

Module 3: Neural Adaptive Fusion: This is the core innovation of the framework. It leverages a learnable neural network to intelligently decide, based on semantic information, how to weigh the contributions from each data source under varying land cover types and observation conditions. By adaptively generating an optimal Digital Surface Model (DSM), it fundamentally resolves the semantic conflicts that are challenging for traditional fusion methods to handle.

Module 4: High-Fidelity 3D Model Generation: As the final step, this module generates detailed models, such as buildings, using techniques like procedural modeling based on the optimal DSM and semantic information. It then applies realistic textures to these models to complete the output of the final 3D product.

Module 1: dual-stream parallel high-fidelity semantic parsing

This module is the cornerstone of the entire framework, and its goal is to provide reliable pixel/point-level semantic prior knowledge for subsequent processing. Due to the fundamental differences in data structure and expression between images and point clouds, we designed two specialized deep learning sub-networks to perform fine-grained semantic segmentation on the data of their respective modalities in parallel.

Image semantic segmentation sub-network: The SegFormer-B2 architecture is adopted. The input image size is 1024 × 1024 pixels. The encoder extracts multi-scale features through a hierarchical Transformer, and the decoder achieves cross-layer fusion through an MLP. To improve the edge segmentation accuracy of buildings, roads, etc., a boundary-aware loss20,21 is introduced, and its expression is:

Among them, \(\:{y}_{i}\) is the ground truth of the boundary, \(\:{\widehat{y}}_{i}\) is the predicted probability, and \(\:\left({B}_{i}\right.\) is the Canny edge mask.

Point cloud semantic segmentation sub-network: Based on the PointNeXt architecture, the input point cloud is downsampled to 4096 points through FPS, and sparse convolution is used to process large-scale data. An expandable linear layer22 is introduced at the feature layer:

Among them, \(\:\gamma\:\) and \(\:\beta\:\) are learnable parameters that adaptively adjust the feature expression ability. It is an improved version of PointNet++. By introducing more effective training strategies and expandable modules, a better balance is achieved between accuracy and efficiency. We combine sparse convolution to efficiently process large-scale urban scene point clouds23.

Training strategy and data augmentation: Training is carried out on a self-built multi-source annotated dataset, and a rich set of online data augmentation strategies are adopted, including randomly rotating, scaling, and color jittering the images, as well as randomly sampling, perturbing, and randomly rotating the point clouds along the gravity direction to improve the generalization ability of the model.

Semantic label transfer from image to point cloud

In order to associate the results of image semantic segmentation in Module 1 with the three-dimensional point cloud (i.e., empty point cloud) generated from images in Module 2, a crucial label transfer step must be performed. The specific process is as follows:

Utilize camera parameters: After calculating the accurate internal and external orientation elements (camera pose and internal parameters) of each image through the Structure from Motion (SfM) process, we obtain the accurate projection relationship from each three-dimensional space point to the image plane.

Back-projection query: For each three-dimensional point \(\:\text{P}\left(\text{X},\text{Y},\text{Z}\right)\) in the empty point cloud, we back-project it onto all the images that can observe this point, obtaining a series of two-dimensional pixel coordinates (u, v).

Label assignment and consistency check: Query the labels of these pixel points (u, v) in the corresponding image semantic segmentation map. Ideally, these labels should be consistent. If inconsistencies occur (e.g., due to occlusion or perspective differences), then the “majority voting” principle is adopted, and the semantic label that appears most frequently is assigned to this three-dimensional point \(\:\text{P}\).

Through this process, we have successfully “lifted” the semantic information of the two-dimensional image to the three-dimensional point cloud space, assigning a clear semantic attribution to each point in the empty point cloud, thus laying the foundation for subsequent semantic-guided registration.

Module 2: Semantic-guided cross-source robust fine registration (SW-ICP)

This module aims to solve the aforementioned geometric inconsistency problem, that is, to accurately align the source point cloud \(\:{\mathcal{P}}_{\text{src}}={\left\{{p}_{i}\right\}}_{i=1}^{N}\) generated from UAV images with the target point cloud \(\:M{Q}_{tgt}={\left\{{q}_{j}\right\}}_{j=1}^{M}\) obtained by LiDAR. To this end, we designed the Semantic Weighted Iterative Closest Point (SW - ICP) algorithm24. By deeply integrating high - dimensional semantic information into the geometric optimization process, this algorithm fundamentally improves the registration accuracy and robustness of the traditional ICP framework in complex scenarios.

The core idea of the SW - ICP algorithm is to use semantic information to guide the corresponding point search and error function construction at each iteration step.

Semantic - constrained corresponding point search

The first core innovation of the algorithm lies in its corresponding point search strategy. For each point \(\:{p}^{{\prime\:}}{}_{i}\) in the source point cloud \(\:{\mathcal{P}}^{{\prime\:}}=\mathbf{R}{\mathcal{P}}_{src}+\mathbf{t}\) after the current transformation (R, t), we no longer blindly search for its nearest neighbor in the entire target point cloud \(\:{Q}_{tgt}\). Instead, we use the semantic labels \(\:L\left(\cdot\:\right)\) obtained in Module 1 to constrain the search space. The set of matching candidate points \(\:{Q}_{\text{cand}}\) is strictly limited to the subset of target points with the same semantic label as \(\:{p}^{{\prime\:}}{}_{i}\) :

In this way, the algorithm only searches within logically consistent categories (e.g., building to building, vegetation to vegetation), avoiding a large number of incorrect matches caused by the adjacency of ground objects from the source.

To address the potential issue of semantic inconsistencies between different data sources (e.g., when the same object is assigned different labels in the two point clouds due to segmentation errors or sensor differences), our search strategy does not employ a hard constraint.Specifically, the algorithm gives priority to searching for correspondences within subsets of points that share the same semantic label. However, for a point in the source cloud that cannot find a semantically identical counterpart in the corresponding region of the target cloud, the algorithm adaptively relaxes the constraint. It allows searching within semantically similar categories (e.g., “ground” and “road”) or within a small geometric neighborhood. A lower weight is then assigned to these less certain point pairs. This flexible, “semantics-first, geometry-second” strategy significantly enhances the algorithm’s robustness to segmentation noise while retaining the core advantages of semantic guidance.

Subsequently, in this candidate subset, the final corresponding point \(\:{q}_{{j}^{\text{*}}}\) is determined by minimizing the Euclidean distance:

Multi - factor weighting and optimization objective function

The second core innovation of the algorithm is to assign a dynamic, multi - factor reliability weight \(\:{w}_{i}\) to each pair of matching points \(\:\left({p}_{i},{q}_{{j}^{\text{*}}}\right)\). This weight enables the algorithm to pay more attention to those point pairs with rich information and high reliability during optimization. The weight \(\:{w}_{i}\) is obtained by multiplying factors from two dimensions: semantics and geometry:

Among them: the semantic weight \(\:{w}_{sem,i}\) ensures the logical consistency of the matching. Since the matching is carried out within the same category, this weight is given a relatively high value to strengthen the authority of semantic constraints.

The geometric weight \(\:{w}_{\text{geom}i}\) evaluates the structural significance of the position where the point pair is located. Point pairs located in areas with stable structures and distinct features (such as building corners and eave edges) are considered more reliable geometric “anchor points” and are therefore given higher weights; conversely, point pairs located in flat and featureless areas have lower weights.

Finally, the optimization objective of the SW-ICP algorithm is to solve a weighted least-squares problem to find the optimal rotation matrix \(\:{\mathbf{R}}_{opt}\) and translation vector \(\:{\mathbf{t}}_{opt}\) such that the sum of the weighted squared distances of all matched point pairs is minimized:

Among them, \(\:\text{K}\) is the number of valid corresponding point pairs found in this iteration. This optimization problem can be efficiently solved by methods such as standard singular value decomposition (SVD). The entire process iterates repeatedly until the transformation parameters (R, t) converge, thereby achieving high-precision and high-robustness cross-source point cloud registration.

As shown in Fig. 2, in the mixed feature scene, the traditional ICP is prone to fall into local minima in the optimization trajectory due to the lack of semantic constraints Fig. 2a; while the SW-ICP divides the search space by semantic categories and decomposes the complex non-convex problem into convex optimization problems in multiple semantic subspaces Fig. 2b, and finally converges to the global optimal solution.

Module 3: neural adaptive optimal fusion

The objective of this module is to resolve semantic inconsistencies and to generate an optimal Digital Surface Model (DSM). At its core, the module constructs a data-driven, learnable fusion decision model to replace the weight allocation strategies of traditional methods, which typically rely on manual heuristics or simple geometric rules. The resulting DSM is a regular 2.5D grid, where each planar location (x, y) corresponds to a single, optimal elevation value. This DSM serves as the key geometric foundation for the subsequent generation of the complete 3D model, as described in Module 4.

Fusion Model:

For any pixel\(\:(\text{x},\text{y})\)in the grid, its final fused elevation \(\:{\text{Z}}_{\text{f}\text{u}\text{s}\text{e}\text{d}}\) is calculated by the following formula:

Where \(\:{\text{Z}}_{\text{u}\text{a}\text{v}}\:\)and \(\:{\text{Z}}_{\text{l}\text{i}\text{d}\text{a}\text{r}}\) are the elevation values from the UAV-SfM model and the LiDAR point cloud at that pixel location, respectively. The weight\(\:\:\text{w}\:\)is determined by a small neural network (a three-layer multi-layer perceptron, MLP):

The Softmax function ensures that the sum of the weights is 1. The input feature vector \(\:\text{F}(\text{x},\text{y})\)includes the key information driving the decision:

Semantic feature\(\:{\text{F}}_{\text{sem}}\): The one-hot encoding of the semantic category of the pixel (x, y).

Data quality feature\(\:{\text{F}}_{\text{q}\text{u}\text{a}\text{l}\text{i}\text{t}\text{y}}\):

For UAV data (\(\:{\text{Z}}_{\text{u}\text{a}\text{v}}\)): This includes the normalized local image texture richness (measured by the standard deviation of image gradients) and the multi-view geometry reprojection error.

For LiDAR data (\(\:{\text{Z}}_{\text{l}\text{i}\text{d}\text{a}\text{r}}\)): This includes the local point cloud density and elevation variance.

Geometric consistency feature \(\:{\text{F}}_{\text{g}\text{e}\text{o}}\): The absolute difference in elevation between the two data sources, \(\:|{\text{Z}}_{\text{u}\text{a}\text{v}}-{\text{Z}}_{\text{l}\text{i}\text{d}\text{a}\text{r}}|\).

Training and Learning:

The MLP network is trained in a supervised manner to learn the optimal fusion strategy. To this end, we designated dedicated training patches (approximately 100 m x 100 m each) within our two experimental sites, ensuring they contained a variety of typical land cover types. Within the accessible and representative portions of these training patches, we conducted a high-density ground survey (grid spacing < 0.5 m) using a Leica TS60 total station and high-precision GNSS-RTK. This process allowed us to generate local, centimeter-level ground truth Digital Surface Models (True-DSMs), which serve as the gold standard for our supervised learning.

We acknowledge that acquiring data of this accuracy over large areas in complex environments (such as on rooftops or in the center of dense forests) is extremely challenging. Therefore, our strategy is to leverage these high-precision sample regions to train a fusion model that can generalize to the entire scene. Although this method is costly, it provides the necessary rigorous foundation for validating the effectiveness of our high-precision approach.

During training, the network’s input is the feature vector FFF corresponding to each grid cell within the training patches. Its loss function is defined as the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) between the predicted fused elevation and the ground truth elevation:

Through backpropagation, the network automatically learns a complex, non-linear set of rules to determine how much trust to place in each data source under specific semantic, quality, and geometric conditions, thus achieving optimal adaptive fusion.

Module 4: generation of high-fidelity realistic 3D model

This module is responsible for giving a sense of realism to the high-precision geometric model.

DSM-to-Mesh Conversion: The optimal fused DSM generated in Module 3 is converted into a triangular mesh model (Mesh). Since a DSM is inherently 2.5D data, it cannot represent vertical surfaces. Therefore, for features with vertical structures, such as buildings, we employ a semantics-based procedural modeling approach. This method involves first extracting the building footprints from the DSM and then extruding them vertically according to their height information within the DSM. This process generates 3D geometries that include the building facades.

By solving a global energy minimization problem, select the texture source image with the least occlusion, maximum resolution, and best viewing angle for each triangular patch, and perform gradient - domain fusion at the seams to eliminate color jumps and generate a seamless and realistic final texture25.

Experimental setup and protocol

Test sites and data collection

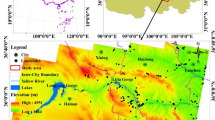

To comprehensively evaluate the performance and generalization ability of the method, we selected two typical complex scenarios with significant differences, as shown in Fig. 3.

Experimental Area 1 (Urban CBD): Located in the center of a megacity in China, with an area of \(\:1.8{\hspace{0.33em}\text{k}\text{m}}^{2}\). This area has dense buildings with significant height differences (\(\:50\hspace{0.33em}\text{m}\sim\:350\hspace{0.33em}\text{m}\)), contains a large number of reflective materials such as glass curtain walls and metal roofs, and has deep shadow areas caused by high - rise buildings. Data sources: A DJI M300RTK drone equipped with a \(\:\text{P}1\) full - frame camera was used to obtain five - direction oblique images (GSD = 2.5 cm); on the ground, 30 stations were set up using a Riegl VZ − 400i terrestrial 3D laser scanner to obtain high - density point clouds.

Experimental Area 2 (Mountainous Forest Area): Located in a typical karst mountain area in South China, with an area of \(\:2.5{\hspace{0.33em}\text{k}\text{m}}^{2}\). This area has a highly undulating terrain, with a vegetation coverage rate of over \(\:80\text{\%}\). The canopy of the subtropical evergreen broad - leaved forest is dense, and the terrain under the forest is complex. Data sources: An orthophoto (GSD = 5 cm) was obtained using a fixed - wing drone with a longitudinal and transverse flight path planning, and a RIEGL VUX − 1UAV airborne LiDAR scanner (point density > 30 points/m²) was simultaneously carried.

Self-built semantic annotation dataset

Given the discrepancies between public datasets and the complex scenarios in our study—in terms of sensor types, data resolution, and feature characteristics—we constructed a high-quality, multi-modal semantic annotation dataset. This dataset was specifically designed to train and validate the proposed dual-stream semantic segmentation network. The construction process was as follows:

Dataset Composition and Scale: The dataset was curated from the raw data of our two experimental sites and similar prior projects. We selected 500 representative high-resolution oblique UAV images (GSD < 3 cm) and 10 distinct LiDAR point cloud scenes (totaling approx. 500 million points). This collection covers a rich variety of features, including high-rise buildings, glass facades, urban villages, roads, vegetation, and water bodies.

Semantic Class Definition: To align with downstream tasks, we defined six core semantic classes: Building, Road, Vegetation, Water body, Ground, and Vehicle.

Annotation Methodology: We employed a meticulous “image-assisted, point cloud-primary” annotation strategy.

Image Annotation: Pixel-level masks were manually drawn on the 500 images using professional annotation software (e.g., CVAT).

Point Cloud Annotation: In point cloud editing software (e.g., CloudCompare), point-wise labels were assigned using the annotated images as a strong visual reference. This ensures semantic consistency across modalities. For instance, points corresponding to a region labeled ‘Building’ in an image were also assigned the ‘Building’ label.

Quality Control: To guarantee annotation accuracy, a “two-round annotation, one-round review” process was implemented. Each data sample was first annotated by one annotator and then cross-checked and refined by a more experienced expert. Discrepancies were resolved through team discussion. This process resulted in an Inter-Annotator Agreement (IAA) exceeding 98.5%, providing reliable ground truth for training our deep learning models.

Ground truth acquisition and evaluation metrics

Using a Leica TS60 total station and a multi - constellation - supported GNSS RTK, more than 400 check points (CPs) were collected in the two experimental areas and divided into three categories: building corner points, hardened ground (roads/squares), and ground points under vegetation.

The evaluation metrics include:

Point accuracy: Root - mean - square error (RMSE), mean absolute error (MAE).

Model surface quality: Chamfer Distance (CD), Normal Consistency (NC).

Semantic segmentation accuracy: Mean Intersection over Union (mIoU).

Completeness: The ratio of the effective data area of the model to the total area.

Comparison methods and implementation details

We compared SAAF - Net with four methods:

UAV-SfM: Perform 3D reconstruction using only UAV images through Agisoft Metashape.

LiDAR-TIN: Generate DSM through TIN interpolation using only LiDAR point clouds.

ICP-Fusion: Use the classic ICP algorithm for registration, and then perform fusion using a simple average weighting method.

DeepReg-Fusion: A cross-modal registration method based on deep learning proposed in 2021. Perform average fusion after registration. All deep learning models were implemented using PyTorch 2.0 and trained and tested on two NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPUs.

Experimental results and performance evaluation

Semantic parsing and registration accuracy

As shown in Table 1, our two-stream semantic segmentation network achieved an mIoU of over 90% on both images and point clouds, providing reliable semantic priors for subsequent modules. The results in Table 2 clearly show that the SW-ICP algorithm proposed in this paper far exceeds the traditional ICP and the advanced DeepReg methods in terms of registration accuracy. Both the rotation error and the translation error are reduced by an order of magnitude, demonstrating the effectiveness of the semantic guidance strategy.It should be noted that the registration accuracy is highly dependent on the accuracy of the semantic segmentation from Module 1. Segmentation errors can propagate to the registration module, impacting the search for corresponding point pairs and thereby reducing the final alignment accuracy. Our future work will investigate how to quantify and mitigate this error propagation effect.

Quality assessment of the fusion model

Quantitative accuracy analysis.

To objectively evaluate the performance of the SAAF-Net framework, we conducted a rigorous quantitative comparison between it and multiple baseline methods in two experimental areas.

In the urban area, as shown in Table 3, SAAF-Net shows an overwhelming advantage in all indicators. The root mean square error (RMSE) of its final model is only 0.074 m, which is a 51% improvement in accuracy compared to the traditional ICP-Fusion method (0.151 m). Meanwhile, SAAF-Net also leads comprehensively in the chamfer distance (CD) and normal consistency (NC) reflecting the surface quality, as well as the model completeness.

In mountainous areas, as shown in Table 4, the advantages of SAAF-Net are more prominent, especially in terms of vegetation penetration ability. Its ground point accuracy (RMSE) under vegetation reaches 0.195 m, far superior to all other methods. This fully demonstrates that the neural fusion network can intelligently identify the “vegetation” area and fully trust the correctness of LiDAR data.

Qualitative Visual Comparison.

The above quantitative results are further intuitively confirmed in the qualitative visual comparison.

The model quality for the urban CBD experimental site is demonstrated in Fig. 4. The image-only UAV-SfM approach (Fig. 4(a)) suffers from significant model voids and geometric collapses in deep shadow regions. The comparison methods, ICP-Fusion (Fig. 4(b)) and DeepReg-Fusion (Fig. 4(c)), while generating more complete models, still exhibit noticeable geometric distortions and surface noise. As highlighted by the insets, ICP-Fusion produces wavy artifacts and distorted facades, while DeepReg-Fusion’s reconstruction lacks sharp details.In stark contrast, our SAAF-Net (Fig. 4(d)) produces a geometrically complete and highly realistic model. A key advantage, as detailed in the zoomed-in insets of Fig. 4, is SAAF-Net’s ability to accurately reconstruct vertical structures and floor details. The magnified views clearly show that while competing methods lead to warping or blurring of the building facade, our method delivers crisp, well-defined, and accurate geometries. Furthermore, on the recognized challenge of glass curtain walls, SAAF-Net produces the smoothest and most realistic surfaces, free from the distortions plaguing the other methods.

In the mountainous forest region, as illustrated in Fig. 5, the differences between the methods become even more pronounced. The UAV-SfM method (Fig. 5(a)) is entirely unable to capture the true ground surface beneath the dense vegetation, resulting in a smooth but incorrect “canopy surface” model. The comparison methods, ICP-Fusion (Fig. 5(b)) and DeepReg-Fusion (Fig. 5(c)), while achieving partial penetration, produce models that are fragmented, noisy, and fail to represent a continuous terrain.

In contrast, SAAF-Net (Fig. 5(d)), guided by its intelligent fusion strategy, fully trusts the LiDAR data in these vegetated areas. This allows it to generate a clear and coherent under-canopy terrain, effectively a Digital Terrain Model (DTM). The superiority of our method is highlighted in the “Under-Canopy Detail” inset, which directly juxtaposes the clean terrain from SAAF-Net against the noisy, incomplete surface from DeepReg-Fusion (right inset panel). For steep, rocky slopes, SAAF-Net also demonstrates the best performance in preserving fine topographical features, accurately capturing the terrain’s natural complexity without the artifacts present in other methods.

To investigate the internal mechanism by which SAAF-Net achieves its high-quality fusion, we visualized the learned adaptive weights, as shown in Fig. 6. This figure presents a co-registered orthophoto (Fig. 6(a)), its corresponding semantic segmentation map (Fig. 6(b)), and the learned weight map (Fig. 6(c)). A color bar is provided to interpret the weight map, where deep blue signifies full trust in UAV-SfM data, and deep red indicates full trust in LiDAR data.

The visualization reveals an intelligent, semantic-driven decision process. For instance, in vegetation areas (identified as green in Fig. 6(b)), the weight map (Fig. 6(c)) shows a deep red. This indicates that the network, guided by the semantic class, correctly assigns a high weight to the LiDAR data, leveraging its inherent advantage in penetrating vegetation canopies to capture the true ground elevation. Conversely, for building rooftops (identified as gray in Fig. 6(b)), the weight map displays a deep blue. This demonstrates that the model intelligently relies on the UAV-SfM data, which excels at capturing the fine geometric structures and textures of rooftops. Notably, on flat road surfaces, the map exhibits a purple hue, representing a balanced fusion that integrates the strengths of both data sources.

This spatial correspondence between semantic categories and fusion weights provides compelling evidence that our network has successfully learned an interpretable and effective decision-making logic. It adaptively prioritizes the most reliable data source for each distinct land cover type, thereby achieving an optimal and context-aware fusion.

Ablation study

To verify the effectiveness of each module in SAAF - Net, we conducted an ablation study on the urban area data, as shown in Table 5. The results clearly show that from the introduction of semantic search, to the addition of complete weights (complete SW - ICP), and finally to the neural adaptive fusion, each step has made an indispensable contribution to the improvement of the final result, proving the rationality of our framework design and the necessity of each module.

Analysis of computational performance and efficiency

The computational overhead of SAAF-Net mainly occurs in the offline model training stage. In the inference stage, for the urban scenario of \(\:1.8{\hspace{0.33em}\text{k}\text{m}}^{2}\) (approximately 200 million LiDAR points and 3000 images), the total time consumption is about 3.8 h, which can meet the timeliness requirements of most surveying and mapping production projects.The detailed performance analysis of each module is shown in Table 6:

Discussion

Interpretation of core findings: the role of semantics as a “meta-constraint”

The key to the success of SAAF-Net lies in the in - depth integration of the high - level cognitive information of “semantics” into the entire geometric calculation process of 3D reconstruction. In this framework, semantics is no longer simply a feature label but a “meta - constraint”. In the registration stage, it normalizes an originally ill - posed optimization problem by constraining the search space and reshaping the loss function; in the fusion stage, it guides an expert system that originally relied on manual rules by serving as the core input of the decision - making network. This paradigm shift represents a qualitative leap from “processing geometry” to “understanding and optimizing geometry”.

Paradigm shift: from geometric matching to semantic - geometric collaborative reasoning

This study marks an important paradigm shift in the field of multi - source data fusion. Traditional methods follow the “geometry - geometry” matching logic, attempting to find correspondences in a pure geometric space, which proves ineffective in the face of modal differences and complex environments. SAAF-Net, on the other hand, creates a collaborative reasoning path of “geometry \(\:\to\:\) semantics \(\:\to\:\) geometry”. It first abstracts low - level geometric information into high - level semantic concepts, then conducts reasoning and optimization in the joint space of the semantic and geometric spaces, and finally projects the optimized results back to the geometric space. This process is closer to the cognitive mode of the human visual system: we do not understand a scene by matching every pixel but first identify “this is a building” and “that is a tree”, and then refine our perception of the scene based on the structure and relationships of these objects.

Implications for the construction of digital twins

This study has profound implications for the construction of true digital twins. An effective digital twin not only needs to be “geometrically similar” but also “semantically and functionally similar”. Due to its inherent semantic consistency and high precision, the model generated by SAAF-Net can directly serve as an object carrier for physical properties, social functions, and management information in a digital twin platform. For example, a mesh labeled as “road” can be assigned traffic flow attributes, and an object labeled as “building” can be associated with information such as energy consumption and property rights. This lays a solid data foundation for the advanced applications of digital twins from “visualization” to “analysis, simulation, and prediction”.

Limitations and future research directions

Although SAAF-Net has made significant progress, there is still room for optimization.

Limitations: (1) The performance of the model highly depends on the accuracy of semantic segmentation, and segmentation errors will propagate backward. (2) The generalization capability of the model for new and morphologically specific features not seen in the training set needs further testing. (3) Training the neural fusion network requires high - precision local ground - truth data, which is costly to obtain.

Future prospects:

\(\:4\text{D}\) Dynamic Fusion and Change Detection: Introduce the time dimension into the SAAF-Net framework, study the fusion of time-series data, and achieve the modeling and analysis of dynamic processes such as urban changes and geological disasters by introducing the temporal consistency loss. \(\:4\text{D}\)

Hybrid Scene Representation: Combine the advantages of the explicit Mesh generated by SAAF-Net and the implicit representation such as NeRF to construct a hybrid three-dimensional scene model. Use Mesh for regular objects (such as buildings) and neural fields for complex and unstructured objects (such as vegetation and clouds) to achieve the optimal balance between storage efficiency and visual effects.

End-to-End Differentiable Fusion Framework: Design a fully end-to-end differentiable network to unify the SfM, registration, and fusion processes under a global optimization objective, allowing gradient information to flow freely in the entire reconstruction chain and achieving truly globally optimal three-dimensional reconstruction.

Fusion of World Model and Large Language Model (LLM): Explore the combination of SAAF-Net with the latest world models or LLM. Utilize the powerful common-sense reasoning and knowledge association capabilities of LLM to perform consistency verification and relationship reasoning on the generated semantic scenes (e.g., a “bridge” must “span” over a “river” or a “road”) and construct a structured and knowledge-based \(\:3\text{D}\) scene graph to promote digital twin towards true “cognitive twin”.

Conclusion

This paper systematically studies the theories and methods of multi-source three-dimensional data fusion under complex terrains. Aiming at the geometric and semantic gaps in traditional technical routes, an innovative semantic-aware adaptive fusion framework, SAAF-Net, is proposed. Through the collaborative work of four core modules, namely dual-stream parallel semantic parsing, semantic-guided robust registration, neural adaptive optimal fusion, and high-fidelity texture mapping, this framework successfully combines the advanced cognitive abilities of computer vision with the precise geometric calculations of surveying and mapping science. A large number of experiments in typical complex urban and mountainous scenes prove that the method in this paper significantly outperforms the existing mainstream technologies in key indicators such as the geometric accuracy, surface quality, integrity, and semantic consistency of the model. SAAF-Net not only provides an effective solution to the current technical bottlenecks in high-precision surveying and mapping, but more importantly, the “semantic - geometric” collaborative processing paradigm it represents opens up a new path for constructing the next-generation high-fidelity and intelligent digital twin world, with important theoretical value and broad application prospects.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to proprietary restrictions but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Fuller, A., Fan, Z., Day, C. & Barlow, C. Digital twin: enabling technologies, challenges and open research. IEEE access. 8, 108952–108971. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.2998358 (2020).

Danielsen, F. et al. Community monitoring of natural resource systems and the environment. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 47 (1), 637–670. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-012220-022325 (2022).

Ba, R., Deng, Q., Liu, Y., Yang, R. & Zhang, H. Multi-hazard disaster scenario method and emergency management for urban resilience by integrating experiment-simulation-field data. J. Saf. Sci. Resil. 2 (2), 77–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnlssr.2021.05.002 (2021).

He, B., Yuan, X., Qian, S., Li, B. & May 31, Carbon Neutrality: A Review. ASME. J. Comput. Inf. Sci. Eng. December 2023; 23(6): 060809. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4062545 (2023).

Kovanič, E. et al. Review of photogrammetric and lidar applications of UAV. Appl. Sci. 13 (11), 6732. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13116732 (2023).

Kholil, M., Ismanto, I. & Fu’Ad, M. N. 3D reconstruction using structure from motion (SFM) algorithm and multi view stereo (MVS) based on computer vision. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering (Vol. 1073, No. 1, p. 012066). IOP Publishing. (2021)., February https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/1073/1/012066

Feng, S., Wu, X. & Cao, J. A survey of multi-view stereo 3D reconstruction algorithms based on deep learning. Digit. Signal Proc. 105291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsp.2025.105291 (2025).

Štroner, M., Urban, R., Lidmila, M., Kolár, V. & Kremen, T. Vegetation filtering of a steep rugged terrain: the performance of standard algorithms and a newly proposed workflow on an example of a railway ledge. Remote Sens. 13 (15). https://doi.org/10.3390/rs13153050 (2021).

Hu, Q. et al. Learning semantic segmentation of large-scale point clouds with random sampling. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 44 (11), 8338–8354. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPAML2021.3083288 (2021).

Kim, M., Stoker, J., Irwin, J., Danielson, J. & Park, S. Absolute accuracy assessment of Iidar point cloud using amorphous objects. Remote Sens. 14 (19), 4767. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs14194767 (2022).

Ye, S., Yan, F., Zhang, Q. & Shen, D. Comparing the accuracies of sUAV-SFM and UAV-LiDAR point clouds for topographic measurements. Arab. J. Geosci. 15 (5), 388. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12517-022-09683-2 (2022).

Sun, R. et al. Optimization of the 3D point cloud registration algorithm based on FPFH features. Appl. Sci. 13 (5). https://doi.org/10.3390/app13053096 (2023).

Mei, G., Tang, H., Huang, X., Wang, W., Liu, J., Zhang, J., … Wu, Q. (2023). Unsupervised deep probabilistic approach for partial point cloud registration. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (pp. 13611–13620)._ https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2303.13290.

Fu, K., Liu, S., Luo, X. & Wang, M. Robust point cloud registration framework based on deep graph matching. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition (pp. 8893–8902). (2021). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2103.04256

Huang, X., Mei, G., Zhang, J. & Abbas, R. A comprehensive survey on point cloud registration. ArXiv Preprint. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2103.02690 (2021). arXiv:2103.

Saidi, S., Idbraim, S., Karmoude, Y., Masse, A. & Arbelo, M. Deep-learning for change detection using multi-modal fusion of remote sensing images: a review. Remote Sens. 16 (20), 3852. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs16203852 (2024).

Sheng, X., Li, L., Liu, D. & Xiong, Z. Attribute artifacts removal for geometry-based point cloud compression. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 31, 3399–3413. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIP.2022.3170722 (2022).

Li, X. & Zhong, Y. Exploration of a network security situational awareness model based on multisource data fusion. Neural Comput. Appl. 35 (36), 25083–25095. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00521-023-08500-5 (2023).

Singh, H., Verma, M. & Cheruku, R. DMFNet: geometric multi-scale pixel-level contrastive learning for video salient object detection. Int. J. Multimedia Inform. Retr. 14 (2). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13735-025-00361-z (2025).

Guo, Y., Shao, Q., Liu, F., Lin, W., Wang, M., Li, Z., … Wang, X. (2025). Urban green space extraction from BJ-2 remote sensing image based SegFormer semantic segmentation model. Canadian Journal of Remote Sensing, 51(1), 2439835.https://doi.org/10.1080/07038992.2024.2439835.

Ngoc, M. Ö. V., Chen, Y., Boutry, N., Chazalon, J., Carlinet, E., Fabrizio, J., …Géraud, T. (2021, November). Introducing the boundary-aware loss for deep image segmentation.In British Machine Vision Conference (BMVC) 2021.

Xie, T. et al. Point-NAS: A novel neural architecture search framework for point cloud analysis. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 32, 6526–6542. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIP.2023.3331223 (2023).

Chen, Y., Li, Y., Zhang, X., Sun, J. & Jia, J. Focal sparse convolutional networks for 3d object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition (pp. 5428–5437). (2022). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2204.12463

de Almeida, L. R., Giraldi, G. A., Vieira, M. B. & Miranda, G. F. Jr Pairwise rigid registration based on riemannian geometry and lie structures of orientation tensors. J. Math. Imaging Vis. 63 (7), 894–916. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10851-021-01037-z (2021).

Liu, C. et al. Three-dimensional texture measurement using deep learning and multi-view pavement images. Measurement 172, 108828. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2020.108828 (2021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

This paper is a sole-authored work. All research design, data collection, analysis, and writing were completed independently by the author.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, A. Research on multi-source data fusion and high-precision mapping method for complex landforms based on computer vision. Sci Rep 16, 3358 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33338-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33338-3