Abstract

Premature flowering in Angelica sinensis (Danggui) triggers severe declines in root yield and medicinal quality5 by reducing bioactive ferulic acid and promoting lignification. Ferulate 5-hydroxylase (F5H), a cytochrome P450 enzyme, drives metabolic flux toward lignin biosynthesis, but its regulatory network and functional dynamics during early flowering remain unresolved. Transcriptomic and functional analyses identified AsF5H (As09G05225) as a key gene upregulated in early-flowering plants, correlating with root lignin accumulation and ferulic acid depletion. Phylogenetic studies confirmed F5H functional conservation across Apiaceae species, while heterologous expression in yeast validated its enzymatic activity in converting ferulic acid to 5-hydroxyferulic acid. Structural modeling pinpointed three substrate-binding residues (ARG98, ALA115, PHE116) critical for regiospecific hydroxylation. Through correlation network analysis, we identified the AP2/ERF transcription factor AsAP2 (As08G00463) as a regulator of AsF5H and support this regulation with transient assay in tobacco. Our findings elucidate a molecular trade-off between lignification and medicinal compound accumulation, providing actionable targets for metabolic engineering or breeding programs to suppress premature flowering effects and enhance root quality in commercial Danggui cultivation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Angelica sinensis, a renowned medicinal herb, has long been valued for its therapeutic properties1. At the heart of its medicinal potential lies ferulic acid, a water-soluble compound that serves as a crucial quality marker, comprising 0.03% to 0.09% of the plant’s raw material2. Beyond its role in quality assessment, ferulic acid exhibits remarkable versatility, transforming into derivatives like salts, esters, ethers, and amides, each offering distinct physiological benefits3,4,5. For example, ferulic acid piperazine aids in treating renal and coronary diseases, while ligustrazine derivatives enhance blood circulation and inhibit platelet aggregation6. Emerging studies have also highlighted its role in combating antibiotic-resistant bacteria and suppressing cancer cell growth3,4,5.

A. sinensis is widely cultivated in the high-altitude regions of western China1. The seeds are sown in early summer, and the resulting seedlings are transferred to a greenhouse in the first autumn. They are then replanted in the field the following spring. The non-lignified roots can be harvested in the autumn of the second year. Alternatively, if left unharvested, the plants continue to grow and produce seeds by mid-summer of the third year1. However, about 40 % of the plants would transit from vegetative growth to the reproductive stage in the second year, which substantially reduces root yield and quality due to lignification and reduction of concentrations of bioactive compounds (e.g., ferulic acid, flavonoids and coumarins)3,4,5,7,8,9. Omics technologies are applied to uncover the regulatory networks driving early flowering in A. sinesis, thereby shedding light on potential avenues for genetic improvement. Dynamic alteration in phenylpropanoid pathway-associated metabolites is closely associated with the differential expression of key catalytic genes, including PAL1, 4CLs, F5H and LACs8. Integrated transcriptomic and metabolomic studies reveal that early flowering is regulated by a complex interplay of photoperiodic (CO, PHYA, LHY, etc.), hormone signaling (GA2OX1, GASA1, etc.), and carbohydrate metabolism (SUS6, Amy2, SUS1, INVA, etc.) pathways, alongside floral development regulators (AGL62, SOC1, MADS8, etc.)3,4,5. While gibberellin biosynthesis genes (GA20OX1) show inconsistent regulation, polyamine metabolism genes (ADC, SAMDC) and vernalization-related factors (VRN1, FLC) are upregulated, accelerating flowering. Downregulation of SOC1 disrupts floral suppression, and photoperiodic cues synergize with sucrose metabolism to promote early flowering3,4,5. These findings highlight the coordinated roles of photoperiodism, hormonal dynamics, and carbohydrate allocation in driving early flowering, providing molecular targets—such as CO, SOC1, and phenylpropanoid genes to mitigate yield loss through metabolic or genetic interventions.

Two high-quality chromosome-level genome assemblies of A. sinensis have been published7,9, enabling unprecedented insights into its medicinal compound biosynthesis. Han et al. employed weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) to dissect the regulatory architecture of coumarin biosynthesis. They identified tissue-specific co-expression modules, notably the “pink” module (associated with esculetin and scopoletin) and the “blue” module (linked to ferulic acid), which highlighted structural genes such as C4H, 4CL, COMT, CCoAOMT, and F6’H. These modules further implicated 79 transcription factors (e.g., MYB, bHLH, WRKY families) as central regulators of coumarin pathways, providing a roadmap for manipulating metabolite flux7. Complementing this, Li et al. integrated genomic, transcriptomic, and metabolomic analyses to decode the biosynthetic machinery of bioactive compounds. Their work revealed lineage-specific expansions in key gene families—terpenoid synthases (TPSs), acyl-CoA carboxylases (ACCs), polyketide synthases (PKSs), and prenyltransferases (PTs)—that drive the production of terpenoids, phthalides, and coumarins9. A critical discovery emerged from their comparison of normal growth roots versus early-flowering roots, where premature bolting significantly reduced essential oil components, particularly phthalides, directly linking this phenotype to diminished medicinal quality. Transcriptional downregulation of biosynthetic genes and altered metabolite profiles underscored the role of dynamic gene regulation in compound accumulation.

Collectively, these studies illuminate the genetic and regulatory networks underlying A. sinensis’s medicinal value, offering actionable targets for enhancing bioactive compound yields through breeding or metabolic engineering. However, the identity of major regulators controlling these networks—particularly those governing critical enzymes like ferulate-5-hydroxylase (F5H) in the phenylpropanoid pathway—remains unresolved. To address this gap, we combined in silico promoter analysis and wet-lab validation to identify a transcription factor that directly regulates AsF5H expression in the roots of early-flowering A. sinensis, bridging genomic insights with functional characterization to unlock precision strategies for metabolic optimization.

Material and methods

RNA data analysis

RNA-seq data of A. sinensis were obtained from the NCBI SRA database, covering RNAs isolated from various tissues and developmental stages (Table S1). The raw data were filtered by SOAPnuke10 (version 1.5.6) and then aligned to the genome assembly using Bowtie211. Gene expression was quantified using RSEM12 and DESeq213 package (Table S2).

Conserved motifs, gene structure, and phylogenetic analysis

The F5H protein sequences of nine representative species were collected from NCBI or Phytozome database. For each dataset, the longest protein sequence was employed if a gene had multiple alternative splicing transcripts, and short protein sequences (less than 50 bp) were also discarded. Then all-against-all comparisons were performed using BLASTP (E-value cutoff: 1e−5). The detailed gene list identified from Apium graveolens, A. sinensis, Arabidopsis thaliana, Coriandrum sativum, Daucus carota, Panax notoginseng, Populus trichocarpa, Solanum lycopersicum, and Vitis vinifera were listed in Table S3. The conserved motif structures of the F5H proteins were predicted using the MEME v5.3.314 with default parameters. Multiple sequence alignment was performed using MUSCLE v3.8.3115, followed by sequence trimming with trimAl v1.416. A phylogenetic tree was constructed using IQ-TREE v1.6.617 with the Maximum Likelihood (ML) method, where all parameters were set to default except for the bootstrap analysis, which was repeated 1000 times. The phylogenetic tree visualization was carried out using the R package ggtree v3.10.118, and the visualization of the F5H conserved motif structures was done using the R package ggplot2 v3.5.119.

F5H cis-elements analysis

The 2-kb upstream sequences (UP2K) of the F5H coding region were extracted. Consensus cis-element motifs of the AP2 transcription factor, including AGCCGCC, GCCGAC, ACCGAC, CATGCA, CACATG, CAACA, CACCTG, CAAATG, CAACTG, ATCGAG, ATCTA, CCGCCTT, AAACCA, and CACCG, were curated from literature. These motifs were then analyzed within the TATA-box region, TATA-CAAT-box region, and the entire UP2K region using a custom PERL script.

Protein structure analysis

The protein structure and its interaction with the substrate were predicted using the “Protenix” server (https://protenix-server.com). The SMILES structure of coniferyl alcohol, the substrate of AsF5H protein, was retrieved by searching the PubChem website. The DNA sequence bound to AsAP2 protein was “ATCTA”. Subsequently, the results were visualized using the software “protein viewer”.

Validation of AsF5H activity in vivo

The gene sequences of F5H from A. sinensis and ATR2 from A. thaliana were codon-optimized and synthesized (Table S4). The final expression vector pRS426-pCCW12-F5H-tCYC1-pTDH3-AtATR2-tCPS1 were assembled by YeastFab method20 and transformed into BY4741 using Frozen-EZ Yeast Transformation II Kit (ZYMO) according to manufacturer’s instructions (Table S5). Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain BY4741 (MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0) was maintained in the laboratory. All the transformants were selected in synthetic dropout medium without uracil medium (SD-URA) plus 2% Glucose. A single colony was inoculated into 5 mL of SD-Ura liquid medium overnight at 30 °C and 220 rpm, and the preculture was transferred to a flask containing 50 mL of fresh medium for 1 day. Ferulic acid (Cat# 1270311,Sigma) was added to a final concentration of 10 mg/L for feeding experiments, and the cultures were incubated with shaking at 30 °C and 220 rpm for 5 days. Mass spectrometry detection was performed on a quadrupole mass spectrometer, Q‐Exactive (Thermo Fisher Scientific) equipped with an electrospray (ESI) source in negative mode. LC-MS/MS chromatography was performed on a Kinetex® 1.7 μm EVO C18(100×2.1 mm) column (Phenomenex).

Luciferase activity assay

The F5H promoter sequence was constructed into the pGreenII 0800-Luc (LUC) vector21, and the AP2 transcription factor CDS region sequence was constructed into the pGreenII-62SK vector21. The pGreenII 62-SK- TF AP2, pGreenII 0800-LUC-promoter F5H and their corresponding empty vectors were independently transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens (GV3101). Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 was obtained from Shanghai Weidi Biotechnology Co., Ltd,and selected on the LB media with kanamycin and rifampicin. The colonies carries with the desired vectors are picked and cultured in LB liquid medium with kanamycin and rifampicin for approximately 36-48 hours.

The cultivated cells were washed with MES buffer and resuspended in the 10 mL with the OD600 to around 1.2-1.6. Tobacco seeds were obtained from College of Life Sciences, Wuhan University. Bacterial solutions carrying the transcription factor and the targeted sequence were mixed in equal volumes, and acetosyringol was added until the final concentration was 150 uM. Tobacco leaves with a growth period of about one month and fully extended were selected. The mixed bacterial solution was injected into the back of the tobacco leaves using a 1 mL syringe. To ensure the consistency of experimental results, the bacterial solution of the control vector and the target vector to be tested were injected into different parts of the same leaf. The plants injected with Agrobacterium were cultured at around 28 °C for 48 hours, and the injected leaves were removed. A portion of the leaves were injected with 1 × D-luciferin (Biotium) using a 1 mL syringe, and the injection volume was determined based on the size and injection position of the leaves. The fluorescence imaging system CCD was used to take pictures and observe whether there was fluorescence in the area of tobacco plants injected with Agrobacterium. Take another part of the leaves injected with Agrobacterium tumefaciens but not injected with D-luciferin, and place them into different pre cooled grinding bowls according to experimental groups. Liquid nitrogen was added and the leaves were ground into powder form. The powder was taken into a 2 mL EP tube and an appropriate amount of lysis buffer was added. The mixture was fully lysed on ice for 15-30 minutes, centrifuged at 12000 r/min for 10 minutes, and the supernatant was taken. The dual luciferase reporter gene detection kit (JKR23008) was then used. 20 uL of lysis buffer was added to the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay plate, 100 μL of Luciferase Substrate was added, mixed well for 30 seconds, and the signal value of fluorescence emitted was measured. After measuring the fluorescence activity, 100 μL of stop&reaction buffer (with Renllia substrate) was added to terminate the reaction. REN was used to balance the systematic errors between various transformations, the relative activity of luciferase was calculated, and whether proteins interact with each other was determined. Four groups of Agrobacterium combinations were transferred into tobacco leaves, and two days later, they were removed and injected with D-fluorescein luminescent substrate. The fluorescence intensity was observed by CCD, and the qualitative and quantitative results are obtained.

Results

AsF5H gene is a genetic switch for ferulic acid

Ferulic acid and lignin biosynthesis originate from the shikimate pathway and proceed through the phenylpropanoid pathway (Fig. 1). Ferulic acid is synthesized via two distinct branches: the COMT pathway, involving enzymes such as cinnamate 4-hydroxylase (C4H), p-coumarate 3-hydroxylase (C3H), and caffeic acid 3-O-methyltransferase (COMT); and the CCoAOMT pathway, which includes 4-coumarate-CoA ligase (4CL), hydroxycinnamoyl-CoA:shikimate/quinate hydroxycinnamoyltransferase (HCT), and caffeoyl-CoA 3-O-methyltransferase (CCoAOMT). The CCoAOMT pathway primarily produces feruloyl-CoA for lignin biosynthesis, whereas free ferulic acid is mainly generated through the COMT pathway. Lignin biosynthesis further involves cinnamoyl-CoA reductase (CCR), cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase (CAD), and F5H. To identify genes associated with reduced root yield and quality—particularly those involved in the decline of bioactive metabolites such as ferulic acid, flavonoids, and coumarins, as well as the induction of root lignification—we retrieved all publicly available RNA-seq datasets for Angelica sinensis from the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA). These datasets encompass transcriptomes derived from a variety of tissues and developmental stages (Tables S1–S2). Our analysis focused on comparing root transcriptomes from early flowering (EF) and normal growth (NG) stages (Fig. 2a). A distinct cluster of genes with positive fold changes was significantly upregulated in EF roots, exhibiting strong statistical significance (−log10(p-value) > 10). In contrast, a smaller number of genes were significantly downregulated. Among the most highly upregulated genes was As09G05225, which encodes ferulate 5-hydroxylase (F5H; CYP84), showing both extreme fold change and statistical significance (−log10(p-value) ~20) (Fig. 2a). The marked upregulation of As09G05225 in EF roots suggests that this gene may play a central role in lignin biosynthesis and associated metabolic shifts during early bolting.

Integrated Multi-Omics Analysis in A. sinensis. (a) Volcano plot of differentially expressed genes (DEGs): Genes significantly upregulated (red) or downregulated (blue) during reproductive growth. As09G05225 (AsF5H) is highlighted as a key upregulated gene. (b) Phylogenetic tree and protein motif analysis: The phylogenetic tree illustrates the evolutionary relationships among various AsF5H gene family members from different species, including A. sinensis (Asi), Apium graveolens (Agr), Arabidopsis thaliana (Ath), Cucumis sativus (Csa), Daucus carota (Dca), Panax notoginseng (Pno), Populus trichocarpa (Ptr), Solanum lycopersicum (Sly), and Vitis vinifera (Vvi). The tree is rooted with three outgroup species. Adjacent to the phylogenetic tree is a motif analysis showing the distribution of 18 conserved motifs across the different gene family members. Each motif is represented by a colored block, with the color key provided on the right. (c) Expression heatmap: This heatmap displays the expression levels of three F5H homologs in various tissues of A. sinensis including flower, leaf, root, seed and stem. The expression levels are represented by color intensity, with darker colors indicating higher expression.

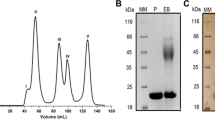

Two additional F5H-like genes—As07G02648 and As01G05286—were also identified in the A. sinensis genome. Phylogenetic analysis of F5H homologs from nine plant species showed that As09G05225 clusters closely with orthologs from Apium graveolens (Agr), Coriandrum sativum (Csa), and Daucus carota (Dca), indicating conserved function within the Apiaceae family (Fig. 2b; Table S3). However, transcriptomic data revealed that only As09G05225 is actively expressed (Fig. 2c), while the other two copies likely represent non-functional duplicates resulting from gene divergence. To validate the enzymatic function of As09G05225, we co-expressed a codon-optimized version of the gene with Arabidopsis thaliana NADPH–cytochrome P450 reductase (AtATR2) in Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain BY4741 (Tables S4–S5). LC-MS analysis of the yeast-expressed enzyme confirmed that As09G05225 encodes an active F5H capable of catalyzing the hydroxylation of ferulic acid to 5-hydroxyferulic acid (Fig. 3a), thereby regulating the metabolic flux toward syringyl lignin biosynthesis during early flowering.

Functional characterization of AsF5H activities in A. sinensis. LC-MS analysis: The left panel shows the retention time (RT) chromatogram of AsF5H enzyme activity, comparing the reaction products with and without the enzyme (EV). The right panel displays the mass spectrum of the reaction products, identifying 5-hydroxyferulic acid as a product of the AsF5H-catalyzed reaction. The mass spectrum includes the molecular ion peak [M+H]+ at m/z 209.05 and fragment ions at m/z 128.03, 189.08, and 131.07. The retention time for 5-hydroxyferulic acid is 3.15 minutes. (b) Protein structure modeling of AsF5H. (c)Catalytic mechanism of AsF5H.

F5H is a cytochrome P450 monooxygenase (EC 1.14.14.1) that catalyzes the regioselective hydroxylation of ferulic acid or coniferaldehyde at the 5-position of the aromatic ring. This reaction produces 5-hydroxyferulic acid or 5-hydroxyconiferaldehyde, precursors essential for the synthesis of sinapyl alcohol and syringyl lignin units. F5H enzymes, classified as CYP84A in Arabidopsis, are typically expressed in tissues undergoing secondary cell wall thickening. Structural modeling of AsF5H revealed a conserved cytochrome P450 architecture, featuring a central heme-binding domain where the iron atom catalyzes oxygen activation. The substrate-binding pocket is precisely positioned above the heme cofactor (orange) and accommodates ferulic acid (modeled in purple) through a network of hydrophobic and polar interactions (Fig. 3b). Key residues include ARG98, which likely forms hydrogen bonds with the ligand’s carboxyl group, and ALA115 and PHE116, which stabilize the aromatic ring. Surrounding hydrophobic residues—LEU377, LEU378, LEU379, ILE375, and LEU491—maintain the integrity of the binding environment. Additionally, ASP306 and GLY310 are located near the active site and may assist in proton transfer or substrate stabilization (Fig. 3c). This structural configuration is consistent with the enzyme’s regiospecific activity and its critical role in lignin biosynthesis.

AP2/ERF regulates the expression of the AsF5H gene

To elucidate the potential transcription factors (TFs) regulating AsF5H, we calculated correlation coefficients between AsF5H expression and all annotated TF genes in A. sinensis. This analysis identified 72 TF candidates showing strong correlations with AsF5H expression (Fig. 4a). To refine this list, we applied stricter criteria—selecting genes with a correlation coefficient > 0.65 and a Benjamini-Hochberg (BH) adjusted P-value < 0.005—indicating strong, statistically significant correlations. Further refinement was achieved through differential expression analysis using the LIMMA package to compare TF expression profiles between NG and EF groups (Fig. 4b, 4c). Among the top candidates, As08G00463 stood out. Functional annotation revealed that As08G00463 is homologous to the Arabidopsis ethylene-responsive transcription factor ERF53, a known regulator of drought stress responses (Table S6).

Correlation analysis and functional ranking of transcription factors (TFs) associated with AsF5H expression. (a) Pairwise correlation matrix of AsF5H with candidate transcription factors. The heatmap shows Pearson correlation coefficients, with positive correlations in blue and negative correlations in red. The curved orange lines highlight TFs that display a strong correlation with AsF5H expression. (b) Heatmap showing differential expression (log₂ fold change) of the top-correlated TFs in root tissue under early flowering (EF) compared to normal growth (NG) conditions. Red indicates upregulation, and blue indicates downregulation. (c) Functional ranking of TF candidates based on their correlation strength with AsF5H. The scatter plot displays.

The AP2/ERF transcription factor family is plant-specific and plays key roles in development, hormone signaling, and responses to environmental stress. Members are characterized by a conserved AP2/ERF DNA-binding domain and are classified into four main subfamilies: DREB, ERF/AP2, RAV, and Soloists. The DREB and ERF subfamilies are further subdivided into subgroups A-1 to A-6 and B-1 to B-6, respectively22. DREB proteins typically bind to Dehydration-Responsive Elements (DRE/CRT), which contain a core A/GCCGAC motif and are involved in responses to abiotic stresses such as drought, heat, and cold22. In contrast, ERF proteins bind to Ethylene-Responsive Elements (EREs), specifically the AGCCGCC (GCC-box) motif, and generally mediate responses to biotic stresses23,24.

A detailed analysis of the AsF5H promoter uncovered a distinct distribution of cis-regulatory elements across three key regions: the TATA–CAAT box, the TATA box, and the upstream 2K (UP2K) region (Fig. 5a). While the TATA–CAAT and TATA box regions contained sparse elements such as ABRE and G-box, the UP2K region displayed a dense and diverse array of motifs, including ABRE, GATA, and G-box elements. Notably, the UP2K region also contains eight tandem repeats of the ATCTA motif. The consistent presence of ABRE and G-box motifs across regions implies their regulatory importance, while the motif-rich UP2K region likely plays a central role in AsF5H transcriptional regulation. The protein structure modeling revealed that As08G00463 with a characteristic AP2/ERF domain, composed of three β-sheets and one α-helix (Fig. 5b). We investigated potential interactions between the AP2 domain and the ATCTA motif, but in silico predictions suggested weak and low-confidence binding (Fig. 5b). Given that A. sinesis is a non-model plant with limited genetic tools, we employed heterologous systems-Nicotiana benthamiana- to examine the interaction between AsAP2 and the AsF5H promoter. Transient expression assays in Nicotiana benthamiana leaves demonstrated that the UP2K fragment drove a significant increase in luciferase activity when co-infiltrated with 35S::AsAP2 (Fig. 5c and 5d). This strong activation in planta suggests that AsAP2 can function as a transcriptional activator of AsF5H under physiological conditions.

Analysis of AsF5H cis-regulatory elements and interaction with the transcription factor AsAP2 (a) Identification of cis-elements in the AsF5H promoter region. The promoter sequence of AsF5H was analyzed. Key motifs (highlighted in red), were enriched within the UP2K region. (b) Structural and functional model of AsAP2-mediated AsF5H regulation. The transcription factor harbors a conserved AP2 DNA-binding domain, composed of three antiparallel β-sheets (red) and one α-helix (blue), which is critical for DNA recognition. The predictive AP2 domain that may interact with ACTCA cis-elements in the AsF5H promoter. (c) Transient dual-luciferase assay in . benthamiana leaves showing activation of the AsF5H promoter by AsAP2. The luminescence signal represents luciferase activity driven by the AsF5H promoter. (d) Quantification of relative luciferase activity corresponding to (c). Data represent mean ± SE (n = 3). Statistical analysis was performed using Student’s t-test (**p < 0.001; ns, not significant).

Discussion

This study elucidates the molecular mechanisms governing ferulic acid metabolism and lignin biosynthesis in A. sinensis during early flowering, highlighting the pivotal roles of the AsF5H gene and its transcriptional regulator, AsAP2. During reproductive growth, AsF5H expression in roots exhibits a significant up regulation (Fig. 2a), redirecting metabolic flux toward lignin biosynthesis (Fig. 1). Consequently, ferulic acid content in roots declines markedly, while lignin precursors such as sinapaldehyde and sinapyl alcohol accumulate8. These findings underscore AsF5H’s role as a key regulatory node regulating ferulic acid metabolism and driving lignin synthesis. The biochemical assays by expressing AsF5H in yeast further confirm that the AsF5H-encoded protein possesses monooxygenase activity, catalyzing the conversion of ferulic acid to 5-hydroxyferulic acid (Fig. 3a), providing enzymatic validation of its metabolic function. Collectively, the interplay between AsF5H upregulation, reduced ferulic acid, and enhanced lignin accumulation offers a mechanistic explanation for prior observations, advancing our understanding of metabolic regulation in A. sinensis. These results align with prior studies3,4,5,7,8,9,25, reinforcing their validity.

AP2/ERF TFs are established regulators of specialized metabolite biosynthesis across plants. In N tabacum, they govern nicotine production26,27, while in Catharanthus roseus and Ophiorrhiza pumila, they control terpenoid indole alkaloid synthesis28,29,30,31. Similarly, Artemisia annua AP2/ERF TFs regulate artemisinin biosynthesis32,33, and solanaceous species rely on these TFs to modulate steroidal glycoalkaloids34,35,36. AsAP2 (As08G00463) was identified as the primary regulator of AsF5H. Tobacco co-transformation assays confirmed AsAP2’s specific binding to AsF5H promoter cis-elements and its transcriptional activation (Fig. 5c and 5d).

This study employed the luciferase assay in N. benthamiana to evaluate the interaction between AsAP2 and the promoter, primarily due to limitations associated with the yeast one-hybrid system. Although Y1H can detect direct DNA-protein binding in a simplified environment, it lacks plant-specific interaction factors, chromatin architecture, and post-translational modifications. These limitations may not only lead to false negatives but also introduce false positives due to non-specific binding or autoactivation phenomena37. In contrast, the transient expression assay conducted in N. benthamiana provides a more native-like physiological context, enabling AsAP2 to recruit co-activators or other regulatory proteins within authentic transcriptional complexes, thereby activating the target promoter more reliably.

While the present study establishes a regulatory role of AsAP2 regulating AsF5H in A. sinesis, further functional validation would provide more definitive evidence in ferulic acid metabolism. Ideally, mutant analysis or transgenic approaches could directly confirm their contributions; however, the absence of an efficient and stable genetic transformation system in A. sinensis currently limits such investigations. Likewise, controlled assessments of ferulic acid abundance and pathway gene expression by qRT-PCR would add complementary support. Nevertheless, it should be noted that both ferulic acid reduction during reproductive growth and the associated transcriptional changes have been consistently reported by several independent research groups, indicating that this is a common and robust phenotype of A. sinensis3,4,5,8,9. Continued methodological advances in transformation and controlled-environment assays will be essential to further dissect these regulatory mechanisms, and the present findings provide a solid foundation for such future studies.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study delineates the molecular basis of ferulic acid metabolism and lignification in A. sinensis. The identification of AsF5H as a metabolic switch and AsAP2 as its regulator provides a foundation for targeted genetic interventions to improve medicinal quality, bridging fundamental research and agricultural application.

Data availability

The original datasets are presented in the Supplementary files (Supplementary data). The data from this study are available from the corresponding author, Tsan-Yu Chiu, at qiucanyu@genomics.cn.

Abbreviations

- AP2:

-

APETALA2

- F5H:

-

Ferulate 5-hydroxylase

- PAL1 :

-

Phenylalanine ammonia-lyase 1

- 4CL :

-

4-Coumarate-CoA ligase

- LAC :

-

Laccase

- CO :

-

Constans

- PHYA :

-

Phytochrome A

- LHY :

-

Late elongated hypocotyl

- GA2OX1 :

-

Gibberellin 2-oxidase 1

- GASA1 :

-

Gibberellic acid-stimulated arabidopsis 1

- GA20OX1 :

-

Gibberellin 20-oxidase 1

- SUS6/SUS1 :

-

Sucrose synthase 6/1

- Amy2 :

-

Alpha-amylase 2

- INVA :

-

Alkaline/Neutral invertase A

- AGL62 :

-

Agamous-like 62

- SOC1 :

-

Uppressor of overexpression of constans 1

- MADS8 :

-

MCM1-agamous-deficiens-SRF 8

- ADC :

-

Arginine decarboxylase

- SAMDC :

-

S-adenosyl methionine decarboxylase

- VRN1 :

-

Vernalization 1

- FLC :

-

Flowering locus C

- C4H :

-

Cinnamate 4-hydroxylase

- COMT :

-

Caffeic acid O-methyltransferase

- CCoAOMT:

-

Caffeoyl-CoA O-methyltransferase

- MYB:

-

MYeloblastosis

- bHLH:

-

Basic helix-loop-helix

- TPSs:

-

Terpenoid synthases

- ACCs:

-

Acyl-CoA carboxylases

- PKSs:

-

Polyketide synthases

- PTs:

-

Prenyltransferases

- UP2K:

-

Upstream 2-kb region

- ATR2 :

-

Arabidopsis thaliana cytochrome P450 reductase 2

- BY4741:

-

Baker’s yeast strain BY4741

- SD-URA:

-

Synthetic dropout medium without uracil

- LC-MS/MS:

-

Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry/mass spectrometry

- ESI:

-

Electrospray ionization

- EVO C18:

-

Enhanced vortex organic C18

- CDS:

-

Coding sequence

- BD:

-

Binding domain

- Y1H:

-

Yeast one-hybrid

- SD-Leu:

-

Synthetic dropout medium without leucine

- AbA:

-

Aureobasidin A

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- LUC:

-

Luciferase reporter gene

- TF:

-

Transcription factor

- LB:

-

Luria-bertani medium

- MES:

-

2-(N-Morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid

- EP tube:

-

Eppendorf tube

- CCD:

-

Charge-coupled device

- REN:

-

Renilla luciferase (Internal Control)

- C4H :

-

Cinnamate 4-hydroxylase

- C3H :

-

p-Coumarate 3-hydroxylase

- HCT :

-

Hydroxycinnamoyl-CoA:shikimate/quinate hydroxycinnamoyltransferase

- CCoAOMT :

-

Caffeoyl-CoA 3-O-methyltransferase

- CCR :

-

Cinnamoyl-CoA reductase

- CAD :

-

Cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase

- EF:

-

Early flowering stage

- NG:

-

Normal growth stage

- CYP84:

-

Cytochrome P450 family 84

- DREB:

-

Dehydration-responsive element binding protein

- ERF:

-

Ethylene-responsive factor

- RAV:

-

Related to ABI3/VP1

- ERE:

-

Ethylene-responsive element

- ABRE:

-

Abscisic acid responsive element

- DRE/CRT:

-

Dehydration-responsive element/CRepeat element

References

Zhang, H. Y., Bi, W. G., Yu, Y. & Liao, W. B. Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels in China: Distribution, cultivation, utilization and variation. Genetic Res. Crop Evol. 59(4), 607–613. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10722-012-9795-9 (2012).

Zhao, K. J. et al. Molecular genetic and chemical assessment of radix Angelica (Danggui) in China. J. Agric. Food Chem. 51(9), 2576–2583. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf026178h (2003).

Li, D., Rui, Y. xin, Guo, S. duo, Luan, F., Liu, R., & Zeng, N. Ferulic acid: A review of its pharmacology, pharmacokinetics and derivatives. In Life Sciences Elsevier Inc. 284 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2021.119921 (2021)

Li, J. et al. Integrated transcriptomics and metabolites at different growth stages reveals the regulation mechanism of bolting and flowering of Angelica sinensis. Plant Biol. 23(4), 574–582. https://doi.org/10.1111/plb.13249 (2021).

Li, M., Li, J., Wei, J. & Paré, P. W. Transcriptional controls for early bolting and flowering in angelica sinensis. Plants https://doi.org/10.3390/plants10091931 (2021).

Yang, C., Yang, W., Chen, Y., Cheng, Q., & Chen, W. Improving renoprotective effects by adding piperazine ferulate and angiotensin receptor blocker in diabetic nephropathy: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. In International Urology and Nephrology Springer Science and Business Media B.V. 54(2):299-307 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11255-021-02927-2 (2022)

Han, X. et al. The chromosome-level genome of female ginseng (Angelica sinensis) provides insights into molecular mechanisms and evolution of coumarin biosynthesis. Plant J. 112(5), 1224–1237. https://doi.org/10.1111/tpj.16007 (2022).

Li, M., Cui, X., Jin, L., Li, M. & Wei, J. Bolting reduces ferulic acid and flavonoid biosynthesis and induces root lignification in Angelica sinensis. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 170, 171–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2021.12.005 (2022).

Li, S. et al. Integrating genomic and multiomic data for Angelica sinensis provides insights into the evolution and biosynthesis of pharmaceutically bioactive compounds. Commun. Biol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-023-05569-5 (2023).

Chen, Y. et al. SOAPnuke: a MapReduce acceleration-supported software for integrated quality control and preprocessing of high-throughput sequencing data. GigaScience https://doi.org/10.1093/gigascience/gix120 (2018).

Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 9(4), 357–359. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.1923 (2012).

Li, B. & Dewey, C. N. RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinform. 12(1), 323. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-12-323 (2011).

Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15(12), 550. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8 (2014).

Bailey, T. L. et al. MEME suite: tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Res. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkp335 (2009).

Edgar, R. C. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 32(5), 1792–1797. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkh340 (2004).

Capella-Gutiérrez, S., Silla-Martínez, J. M. & Gabaldón, T. trimAl: A tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics 25(15), 1972–1973. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btp348 (2009).

Minh, B. Q. et al. IQ-TREE 2: new models and efficient methods for phylogenetic inference in the genomic era. Mol. Biol. Evol. 37(5), 1530–1534. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msaa015 (2020).

Yu, G., Smith, D. K., Zhu, H., Guan, Y. & Lam, T. T. Y. ggtree: an r package for visualization and annotation of phylogenetic trees with their covariates and other associated data. Methods Ecol. Evol. 8(1), 28–36. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.12628 (2017).

Wickham, H. ggplot2 (Springer International Publishing, 2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-24277-4.

Guo, Y. et al. YeastFab: The design and construction of standard biological parts for metabolic engineering in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 43(13), e88. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkv464 (2015).

Hellens, R. P. et al. Transient expression vectors for functional genomics, quantification of promoter activity and RNA silencing in plants. Plant Methods https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-4811-1-13 (2005).

Sakuma, Y. et al. DNA-binding specificity of the ERF/AP2 domain of arabidopsis DREBs, transcription factors involved in dehydration- and cold-inducible gene expression. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 290(3), 998–1009. https://doi.org/10.1006/bbrc.2001.6299 (2002).

Guo, H. & Ecker, J. R. The ethylene signaling pathway: new insights. Curr. Opinion Plant Biol. 7(1), 40–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pbi.2003.11.011 (2004).

Shinozaki, K. & Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. Molecular responses to dehydration and low temperature: differences and cross-talk between two stress signaling pathways. Curr. Opinion Plant Biol. 3(3), 217–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1369-5266(00)80068-0 (2000).

Yu, G. et al. Transcriptome and digital gene expression analysis unravels the novel mechanism of early flowering in Angelica sinensis. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-46414-2 (2019).

De Boer, K. et al. Apetala2/Ethylene response factor and basic helix–loop–helix tobacco transcription factors cooperatively mediate jasmonate-elicited nicotine biosynthesis. Plant J. 66(6), 1053–1065. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04566.x (2011).

Shoji, T., Kajikawa, M. & Hashimoto, T. Clustered transcription factor genes regulate nicotine biosynthesis in tobacco. Plant Cell 22(10), 3390–3409. https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.110.078543 (2010).

Paul, P. et al. A differentially regulated AP2/ERF transcription factor gene cluster acts downstream of a MAP kinase cascade to modulate terpenoid indole alkaloid biosynthesis in Catharanthus roseus. New Phytol. 213(3), 1107–1123. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.14252 (2017).

Udomsom, N. et al. Function of AP2/ERF Transcription Factors Involved in the Regulation of Specialized Metabolism in Ophiorrhiza pumila Revealed by Transcriptomics and Metabolomics. Front. Plant Sci. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2016.01861 (2016).

Van Der Fits, L., & Memelink, J. (n.d.). ORCA3, a Jasmonate-responsive transcriptional regulator of plant primary and secondary metabolism. www.sciencemag.org

van der Fits, L. & Memelink, J. ORCA3, a Jasmonate-responsive transcriptional regulator of plant primary and secondary metabolism. Science 289(5477), 295–297. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.289.5477.295 (2000).

Lu, X. et al. AaORA, a trichome-specific AP2/ERF transcription factor of Artemisia annua, is a positive regulator in the artemisinin biosynthetic pathway and in disease resistance to Botrytis cinerea. New Phytol. 198(4), 1191–1202. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.12207 (2013).

Yu, Z.-X. et al. The jasmonate-responsive AP2/ERF transcription factors AaERF1 and AaERF2 positively regulate artemisinin biosynthesis in artemisia annua L. Mol. Plant 5(2), 353–365. https://doi.org/10.1093/mp/ssr087 (2012).

Cárdenas, P. D. et al. GAME9 regulates the biosynthesis of steroidal alkaloids and upstream isoprenoids in the plant mevalonate pathway. Nat. Commun. 7(1), 10654. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms10654 (2016).

Nakayasu, M. et al. JRE4 is a master transcriptional regulator of defense-related steroidal glycoalkaloids in tomato. Plant J. 94(6), 975–990. https://doi.org/10.1111/tpj.13911 (2018).

Thagun, C. et al. Jasmonate-responsive ERF transcription factors regulate steroidal glycoalkaloid biosynthesis in tomato. Plant Cell Physiol. 57(5), 961–975. https://doi.org/10.1093/pcp/pcw067 (2016).

Springer, N., de León, N., & Grotewold, E. (2019). Challenges of Translating Gene Regulatory Information into Agronomic Improvements. In Trends in Plant Science (Vol. 24, Issue 12, pp. 1075–1082). Elsevier Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tplants.2019.07.004

Acknowledgements

Supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No.2022YFD1201600). We acknowledge Qi Zhou did the Yeast-1-hybrid, Shujie Wang and Feng Zhang did the F5H enzymatic analysis. Xin Jin, Meng Xu., Shiming Li and Kang Yu performed the transcriptome and phylogenetic analysis.

Funding

This study was financially supported by HIM-BGI Omics Center, Hangzhou Institute of Medicine (HIM), Chinese Academy of Sciences, Hangzhou 310018, China. The funder did not participate in the designing, performing, or reporting of the current study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.W. and T.-Y.C. designed and performed the experiments and analyzed the data. J.F. conducted the motif and protein structure analysis. Z.Z. performed the correlation analysis. Q.L. assisted with transcriptome data retrieval. Z.W., J.F., and T.-Y.C. wrote the manuscript. P.W. and T.-Y.C. revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent for publication

All data analyzed in this study were derived from publicly available datasets, with corresponding SRA accession numbers detailed in Supplementary Table 1.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, Z., Fang, J., Liu, Q. et al. AsAP2 transcriptionally activates ferulate 5-hydroxylase, diverting ferulic acid metabolism toward lignin biosynthesis in Angelica sinensis.. Sci Rep 16, 3517 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33378-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33378-9