Abstract

The caisson method is typically employed in foundation pit projects characterized by complex surrounding structures and challenging engineering geological conditions. The sinking process involves complex soil-structure interactions, particularly the sidewall friction between the caisson and the surrounding soil strata. This friction is a critical factor, as it not only determines the feasibility and safety of the sinking operation but also influences the pattern and magnitude of surrounding ground subsidence. This study aims to explore the mechanism of sidewall friction between the caisson and strata and its direct impact on controlling the sinking process and mitigating surrounding subsidence. The analysis is based on the large caisson engineering of Zhuchong Pump Station, located in Xinyang City behind the Chushandian reservoir. By conducting a numerical simulation of the sinking process and analyzing measured data from on-site subsidence monitoring points, this research reveals that the caisson induces a parabolic-shaped subsidence curve in the surrounding ground surface. The magnitude and extent of ground subsidence around the caisson increase with greater sinking depth and with proximity decreasing distance from the sidewall. The study further demonstrates that sidewall friction significantly influences ground subsidence. Specifically, lower friction in the initial sinking phase results in noticeable ground uplift due to reduced constraint on soil displacement. Conversely, higher friction leads to increased ground subsidence as the sinking depth progresses. The study reveals that the influence pattern of friction between the caisson sidewall and the surrounding soil on ground surface subsidence, and lower friction would result in pronounced ground uplift due to reduced constraint on surface displacement during the initial sinking phase, and higher friction would increase ground subsidence as the caisson sinking depth increases. The findings of this research may help provide a technical reference for subsidence control in similar large-scale caisson projects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Caisson, a hollow shell structure of massive, deep foundation elements capable of resisting large vertical and lateral loads, is used in geotechnical and marine engineering by excavating material from within its chamber. It is a robust engineering structure widely employed in foundation and underground construction, with advantages such as requiring no extensive excavation, possessing high structural integrity, and offering excellent durability. The sinking of a caisson relies on its self-weight to overcome the resistance at the base and the friction between the sidewall and surrounding soil. Once it reaches the design depth, the bottom is sealed with concrete. However, the subsidence of caisson may disturb the surrounding soil, leading to deformation and stress redistribution, which can result in functional impairment of adjacent structures. Therefore, it is essential to control the impact of caisson engineering on surrounding soil settlement, ensure both the safety of the caisson project itself and the stability of nearby structures1,2,3.

The research on caisson engineering primarily focuses on soil-structure interaction during sinking process. For instance, a combined finite element and field monitoring study of the Wuhan Yingwuzhou Yangtze River Bridge demonstrated that ground subsidence increases proportionally with sinking depth and can be mitigated by diaphragm walls4. The mechanical behavior of caissons has been extensively investigated. Studies have quantified the distribution of base resistance5,6,7 and developed models for sidewall friction and pressure distribution8,9, confirming their correlation with the soil’s internal friction angle10. Laboratory experiments and numerical simulations have played a crucial role in validation, examining sinking dynamics11, soil pressure12,13,14,15, and bearing capacity16,17,18,19,20. Advanced techniques such as image-based measurements have further analyzed the influence of blade geometry on sinking resistance21. The impact of caisson construction on surrounding soil has also been studied, including soil disturbance22,23,24, subsidence induced by dewatering25, and the correlation between strata subsidence and cutting-edge parameters26,27. Despite these efforts, the specific influence of the frictional force between the caisson sidewalls and the surrounding soil on surface subsidence-particularly in areas behind large reservoir dams- remains a critical knowledge gap that urgently needs to be addressed.

In this study, we first summarize the subsidence characteristics associated with the construction of a large caisson for the Zhuchong Pumping Station, located downstream of the Chushandian Reservoir in Xinyang City, Henan Province. This caisson project is situated behind the reservoir and adjacent to a major traffic route. It is essential to investigate the caisson’s sinking behavior and resulting subsidence characteristics to strictly control deformation of both the caisson itself and the surrounding structures. A key contribution of this work is the analysis of the deformation mechanism of surrounding strata induced by caisson sinking under different lateral friction coefficients between the strata and the caisson sidewall. We then developed a three-dimensional numerical model to study stratum deformation during the sinking process. As far as we know, our research is the first one that studies deformation of surrounding strata induced by a large caisson engineering project located downstream of a reservoir. The study aims to elucidate caisson subsidence behavior and provide actionable technical guidance for optimizing the planning and construction of large-diameter caissons in environmentally sensitive areas downstream of reservoir dams.

Study area

Engineering background

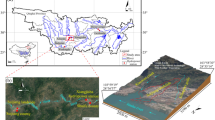

The urban and agricultural water supply demand in Xinyang has been increasing significantly. As part of the corresponding infrastructure, Zhu Chong Pumping Station, located downstream of the Chushandian Reservoir and adjacent to a heavily trafficked road, is a large-scale pumping structure with a depth of 25 m, an outer diameter of 38 m, and an inner diameter of 34 m. A caisson with 2 m thick concrete sidewalls was employed to mitigate potential subsidence of the reservoir embankment and avoid disruption to traffic resulting from groundwater pumping and deep pit open-cut excavation (shown in Fig. 1).

Engineering geological condition

The project is situated in the transitional zone between the eastern low hills of the Tongbai Mountain range and its alluvial plain. Tongbai Mountain range runs from northwest to southeast. Its eastern foothills feature gradually gentler terrain, with elevations ranging from 150 to 400 m. Major rivers in the area include the Huai River, the Youhe River, and the Shihe River. The engineering geology around the Zhuchong Pumping Station of heavy silty loam from the Upper Pleistocene (a period within the Quaternary) and Cretaceous sandy claystone, originating from alluvial and slope deposits. The strata are divided into five primary layers: heavy silty Q3 loam, heavy silty Q2 loam, completely weathered Cretaceous argillaceous sandstone, highly weathered Cretaceous argillaceous sandstone, and moderately weathered Cretaceous argillaceous sandstone (shown in Fig. 2). The mechanical properties of these strata are shown in Table 1.

Numerical model of caisson engineering

Numerical model

To investigate the mechanism of ground subsidence induced by open caisson sinking and to control the impact of caisson construction on surrounding surface subsidence—thereby preventing excessive subsidence that could damage adjacent structures such as embankments and roads—a finite element analysis was conducted using the numerical simulation. A numerical model was established with geometry corresponding to the actual scenario. Material properties were assigned to the model components. The top surface of the geological formation was defined as a free boundary, while the outermost sides and the bottom of the model were designated as fixed boundaries. Frictional interaction between the caisson sidewalls and the surrounding soil was incorporated through contact definitions. Analysis steps were configured to first achieve initial geostatic stress equilibrium. Subsequently, the processes of incremental excavation, sinking, and caisson extension followed by further sinking were simulated, as illustrated in Fig. 4. The sinking of the caisson was simulated primarily by sequentially ‘killing’ the soil elements within the caisson according to a predefined excavation depth and sequence. As the internal soil was removed, both the end resistance and the internal side friction acting on the caisson were reduced. Under the caisson’s self-weight, the stress state was redistributed until a new equilibrium was achieved, thereby simulating the stepwise and dynamic sinking process of the open caisson.

A three-dimensional numerical model was established to study the subsidence mechanism of the surrounding strata induced by the caisson construction, with the objective of mitigating its impact on adjacent structures, including the reservoir and the road. To facilitate the numerical simulation, a quarter model was utilized, leveraging geometric symmetry shown in Fig. 3. The dimensions of the numerical model, 100 m in length, 100 m in width and 50 m in height, were determined based on the stratigraphic characterics and the caisson dimensions. An isotropic constitutive model was adopted for the strata to simplify the computations, a simplification justified by the fact that caisson is located within the upper two strata, extending to a depth of 25 m shown in Fig. 2. The key physical parameters of the strata, as derived from the engineering geological investigation, are presented in Table 1. The caisson structure was assigned material properties corresponding to C30 reinforced concrete, with a Young’s modulus of 30 GPa, a unit weight of 23.5KN/m³, and a Poisson’s ratio of 0.2. In the numerical model, the strata and the reinforced concrete were simulated using the Mohr-Coulomb and linear elastic constitutive models, respectively.

The sinking phases of caisson

The on-site construction of the caisson comprises ten consecutive phases. It begins with the in-situ casting of the first caisson section, followed by the first sinking phase. In this phase, soil is excavated from within the caisson to induce a controlled subsidence of 5 m. Subsequently, the second caisson section is concreted in place, leading to the second sinking phase, where internal excavation is repeated to achieve a further 5-meter descent. This cycle of casting and controlled sinking continues iteratively until the fifth and final sinking phase reaches the designed elevation, as shown in Fig. 4. The caisson sinks primarily under its own weight, which overcomes the friction along its external walls and the resistance at the cutting shoe. Given the project’s location behind the reservoir dam and adjacent to a major traffic route, comprehensive dewatering techniques were employed to enable dry construction. This ensured a stable, dry working environment at the excavation base and allowed for rigorous control of ground deformation.

Simulation results

To facilitate numerical simulation, the geological strata in the model were simplified as isotropic. In the simulation of mechanical behavior, the strata and the sidewall were modeled using the Mohr-Coulomb model and rigid body constitutive models, respectively. According to the characteristics of strata, The friction coefficients at the interface between the strata and the caisson’s external wall, assigned based on the characteristics of each stratum, are shown in Table 2.

Simulation of original friction coefficient

The caisson sinking process and the associated ground subsidence, predominantly caused by sidewall friction, were simulated. The five primary sinking phases and evolution of subsidence are depicted in Fig. 5. The computed ground subsidence subsequent to initial 5-meter sinking phase is presented in Fig. 5a. In this phase, shallow soil layers, characterized by weak lateral restraint and low deformation resistance, undergo limited compression. A localized uplift phenomenon is observed, attributed primarily to the volume displacement of soil resulting from the intrusion of the caisson’s cutting edge. The subsidence patterns at the second phase, corresponding to a 10-meter sinking depth, are shown in Fig. 5b. With increasing sinking depth, strata subsidence develops progressively due to intensified lateral friction, whereas the uplift effect is significantly reduced. The subsidence patterns for the subsequent phases (third, fourth, and fifth) in Figs. 5c-e show that greater sinking depths increases frictional resistance, leading to a corresponding intensification of the subsidence.

Figure 6 illustrates the evolution of radial ground subsidence during the five sinking phases, with all deformation confined within an 18-meter radius. The deformation pattern after the first sinking phase, shown in Fig. 6, is characterized by ground uplift. This uplift reaches a maximum of nearly 1 cm adjacent to the caisson sidewall and diminishes with distance within a 10-meter influence zone. A transition from uplift to subsidence occurs from the second sinking phase onward. Subsequently, both the magnitude of the maximum subsidence and its radial influence range increase progressively with each subsequent sinking phase. At the final (fifth) sinking phase, the maximum subsidence reaches approximately 6.8 cm, with a corresponding influence range of 16 m.

Simulation of reduced friction coefficient

Figure 7 illustrates the ground subsidence resulting from caisson sinking with reduced interfacial friction, achieved by injecting lubricating mud between the caisson exterior and the surrounding strata. As shown in Fig. 7(a), slight ground uplift occurs adjacent to the caisson, attributable to lateral soil compression under the structure’s self-weight. Figure 7b presents the simulated surface subsidence after the second sinking phase at a depth of 10 m. The results clearly indicate that subsidence in Fig. 7b is significantly less pronounced than that in Fig. 5b, demonstrating the effectiveness of friction reduction in mitigating surface settlement. Figures 7c &e reveal a progressive increase in ground subsidence with greater sinking depth. Notably, throughout all sinking stages, the magnitude of subsidence remains consistently lower than that observed in the non-lubricated scenario.

Figure 8 presents the radial ground deformation profiles across five caisson sinking phases under friction reduced conditions. The first sinking phase (Fig. 8a) is characterized by ground heave, with a maximum uplift of 1.6 cm. This value is greater than the 1 cm heave observed in Fig. 6(a) under normal conditions, which can be attributed to the reduced lateral restraint provided by the lubricated interface. The mechanism for this heave involves a transfer of significant skin friction into the surrounding soil during the initial descent. This downward drag force, combined with radial confinement, disrupts the in-situ stress field, leading to a profound stress redistribution and consequent upward displacement of the soil mass, manifesting as a distinct annular heave zone. In the subsequent sinking phases (Fig. 8b and e), the deformation pattern shifts from heave to subsidence. Both the maximum subsidence magnitude and its radial influence range increase progressively, from 0.7 cm to 3.3 cm and from 11 m to 14 m, respectively.

Discussion

The results demonstrate that the original sidewall friction coefficient (Fig. 6) induces a maximum ground subsidence of 6.8 cm near the caisson, which is substantially greater than the 3.5 cm observed under reduced friction conditions (Fig. 8). Conversely, friction reduction leads to more pronounced ground uplift during the initial sinking phase. Furthermore, the radial influence distance of subsidence decreases from 16 m with original friction to 14 m with reduced friction. These findings confirm the critical role of sidewall friction in governing ground deformation patterns. Specifically, higher friction suppresses initial ground uplift by providing greater lateral constraint. However, this same mechanism amplifies cumulative subsidence with increasing sinking depth.

To quantitatively investigate the ground deformation mechanism, the surface displacement monitoring points were positioned along primary caisson axes to track deformation behavior comprehensively shown in Fig. 3(b). Displacement at monitoring points was measured three times daily using a high-precision total station with an accuracy of 0.1 mm. The reliability of our numerical model was then rigorously validated by comparing the on-site monitoring data with simulation results obtained using the reduced friction coefficient across all five sinking phases shown in Fig. 9. The value of ground heave monitored is smaller than that simulated shown in Fig. 8 due to some additional stress effects existing at the construction site. Overall, the measured deformation curves exhibit close agreement to that simulated. This strong correlation confirms the model’s accuracy in capturing the soil-structure interaction. Furthermore, both field data and numerical results conclusively demonstrate that after the initial phase of slight uplift, ground subsidence progressively intensifies in direct response to the increasing caisson sinking depth, a trend driven by the accumulating sidewall friction.

Our simulations definitively establish the sidewall friction coefficient as a critical factor governing the magnitude and pattern of ground deformation. A comparative analysis of Figs. 6 and 8 confirms that a reduction in this coefficient is an effective strategy for mitigating overall ground subsidence throughout the sinking process. Paradoxically, this beneficial effect is accompanied by a counterintuitive response in the initial phase: lower friction leads to more pronounced ground uplift. This phenomenon is attributed to the diminished lateral constraint provided by the surrounding soil, which allows for greater upward displacement as the caisson’s cutting edge intrudes into the ground with minimal resistance. Consequently, engineers must balance the long-term benefit of reduced subsidence against the short-term risk of initial heave when designing friction mitigation measures.

Conclusion

This study investigates the ground deformation mechanisms induced by the sinking process at Zhuchong Pumping Station through comprehensive numerical simulation. Our computational model quantitatively elucidates the evolution of ground deformation across five distinct sinking phases under two critical friction coefficients. The simulations demonstrate that reducing the sidewall friction coefficient significantly mitigates ground subsidence. The analysis also reveals a counterintuitive initial response: pronounced ground uplift during the first sinking phase, which is attributed to the week constraint offered by the overlying stratum. Spatially, the resultant subsidence is predominantly confined to the immediate vicinity of the caisson, exhibiting a radially attenuating profile. Furthermore, from the second phase onward, the subsidence magnitude shows a progressive intensification proportional to the incremental sinking depth.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in the manuscript and available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Niu, J. D. et al. Structural analysis for the Caisson of the pump room of Kidurong power plant based on finite element method. Water Resour. Hydropower Eng. 50 (9), 89–97 (2019).

Regtop, J. & Feddema, A. Investigations on the sinking process of large pneumatic caissons. Geotechnik 44 (4), 260–280 (2021).

Faizi, K., Faramarzi, A., Dirar, S. & Chapman, D. Development of an analytical model for predicting the lateral bearing capacity of Caisson foundations in cohesionless soils. Ocean. Eng. 218, 108112 (2020).

Deng, Y. S. et al. Stress of large cylindrical Caisson structure and its adjacent settlement. Rock. Soil. Mech. 36 (02), 502–508 (2015).

Guo, M. W. et al. Study on the variation of the bottom resistance during sinking stage of super large Caisson foundation. Chin. J. Rock Mechan. Eng. 40 (S1), 2976–2985 (2021).

Wang, Z. Z., Gong, W. M. & Dai, G. L. Numerical simulation analysis of a South anchorage Caisson. J. Nanjing Inst. Technol. (Natural Sci. Edition). 15 (01), 16–22 (2017).

Zhang, Z. C. et al. Analysis on sudden sinking behaviors of massive open Caisson in deep-thick soft clay area. Chin. J. Undergr. Space Eng. 16 (3), 933–943 (2020).

Jiang, B. N. et al. On-site monitoring of lateral pressure of ultra-deep large and subaqueous open Caisson during construction. Rock. Soil. Mech. 40 (04), 1551–1560 (2019).

Zhang, Z. J. et al. Coupling effects of pressed Caisson and uplift piles on surface settlement. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 46 (S2), 119–123 (2024).

Liang, S. J., Xu, W. & Xu, Z. Y. Earth pressure and frictional resistance analysis on open Caisson during sinking. J. Tongi Univ. (Natural Science). 42 (12), 1826–1832 (2014).

Handayanu Swamidas, A. S. J. & Bootton, M. Behavior of tension foundation for offshore structures under extreme pull-out loads. Proceedings of 18th International Conference on Offshore Mechanics and Arctic Engineering, St. johns. Newfoundland, Canada, 635–641 (1999).

Chiou, J. S. & You, J. Q. Three-dimensional finite element analysis of laterally loaded Bridge Caisson foundations in gravelly soil. Acta Geotech. 15 (11), 3151–3166 (2020).

Zhang, J. & Nepomuceno, E. G. Numerical simulation on the whole sinking process of open Caisson with an improved SPH method. Math. Probl. Eng. 1–9 (2021).

Mu, B. G., Ling, X., Zheng, W. F., Mei, G. X. & Ni, P. P. Model test and numerical simulation of open Caisson foundation under long-term lateral loading. Ocean Eng. 312, 119276 (2024).

Zhou, H. X. et al. Study of sinking resistance of large and deep caisson based on centrifugal model test.. Rock and Soil Mechanics 40(10), 3969–3976 (2019).

Qin, S. Q. et al. Research on design and sinking methods for super large Caisson foundation. Bridge Constr. 50 (05), 1–9 (2020).

Guo, M., Dong, X. & Li, J. Study on the earth pressure during sinking stage of super large caisson foundation. Appl. Sci. 11(21), 10488 (2021).

Zhang, Y. K., Li, D. Y. & Mao, D. W. Bearing capacity and soil deformation around modified Suction Caisson in clay under monotonic horizontal loading. Mar. Geores Geotechnol. 41 (9), 959–968 (2023).

Li, D. Y., Feng, L. Y. & Zhang, Y. K. Model tests of modified Suction caissons in marine sand under monotonic lateral combined loading. Appl. Ocean. Res. 48, 137–147 (2014).

Xia, H., Zhou, X., Zhou, M., Niu, F. & Zhang, X. Capacity of caissons in stiff-over-soft clay under combined V–HM loadings. Ocean. Eng. 229, 109007 (2021).

Chavda, J. T., Mishra, S. & Dodagoudar, G. R. Experimental evaluation of ultimate bearing capacity of the cutting edge of an open Caisson. Int. J. Phys. Modelling Geotechnics. 20 (5), 281–294 (2020).

Zhou, S., Zhou, M., Tian, Y. & Zhang, X. Numerical investigation of caisson with pad-eye stiffener installation into nonhomogeneous clay. Appl. Ocean. Res. 121, 103077 (2022).

Bai, Z., Gao, Y. & Yang, B. Key technologies for construction control of large double sinking wells in urban core areas in complex environments. Int. Core J. Eng. 9 (9), 113–119 (2023).

Liu, M. et al. Mechanical performance of deep circular Caisson sinking in deep layered soft soil. Math. Probl. Eng. 2022 (1), 5918374 (2022).

Mu, B. G. et al. Effect of supporting soil stiffness on internal force of Caisson during sinking. J. Southeast. Univ. (Natural Sci. Edition). 42 (5), 981–987 (2012).

Tan, G. H. et al. Settlement analysis of Caisson foundation under main tower of a long span cable-stayed Bridge for highway and railway. Rock. Soil. Mech. 40 (03), 1113–1120 (2019).

Ronan, R., Brian, B. S. & Byron, W. B. Undrained bearing capacity of the cutting face for an open Caisson. Géotechnique 72, 7, 632–641 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The study is supported by Henan Province Natural Science Foundation General Project (No. 242300420227) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 42207187).

Funding

The study is supported by Henan Province Natural Science Foundation General Project (No. 242300420227, 242300420225), National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 42207187), Key Research & Development and Promotion Projects of Henan Province (No. 242102320346) and the Key Scientific Research Projects of Henan Province Colleges (No. 23A440010).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Zheng Xu, Lejun Wang, Jinhui Tian and Xingsheng Zhang mainly developed the geotechnical numerical model and performed numerical analyses. Xingsheng Zhang, Jinhui Tian, Yurong Cui and Shuangshuang Wang wrote the main manuscript text, and all authors reviewed and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, Z., Wang, L., Cui, Y. et al. Research on ground deformation induced by large caisson construction at the Zhuchong pumping station in Xinyang, China. Sci Rep 16, 3516 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33489-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33489-3