Abstract

Skin cancer, particularly melanoma, remains one of the most lethal diseases globally due to challenges in early detection and diagnosis. Conventional image segmentation models often face difficulties due to the high variability in lesion appearance and their limited ability to focus on critical features, thereby compromising diagnostic accuracy. In this study, we introduce an advanced AI-driven framework that integrates a Scaled Dot Attention Mechanism (SDAM) with a modified UNet architecture to improve skin lesion detection. The SDAM, applied as an attention mechanism between the encoder and decoder stages of the UNet, allows the model to prioritize relevant lesion areas and extract essential features while reducing noise. We evaluate the proposed model using the HAM10000 dataset, a diverse collection of skin lesion images, and test it on two additional datasets: ISIC (Preliminary) and PH2 (Preliminary), to assess generalization across various skin lesion types. Our model achieves significant improvements in melanoma detection with Dice scores between 0.97 and 0.988, accuracy ranging from 97.8% to 98.3%, and substantial enhancements in sensitivity. These results outperform baseline models, including standard UNet (Dice score: 0.85, accuracy: 88.4%) and DenseNet (Dice score: 0.87, accuracy: 90.1%). Furthermore, the model’s performance was compared to state-of-the-art methods such as Attention UNet, UNet++, and TransUNet, consistently demonstrating superior results. Statistical analysis via a paired t-test reveals a significant performance boost (p-value = 0.02), further validating the effectiveness of the SDAM-enhanced approach. These findings highlight the potential of AI in advancing early skin cancer detection and diagnosis, with the SDAM-UNet framework offering prospects for personalized care and real-time clinical integration. Additionally, our model’s performance across multiple metrics such as precision, recall, F1-score, and IoU showcases its robustness in classifying both melanoma and benign skin lesions, reinforcing its utility in clinical practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Skin Cancer, especially Melanoma, is still a significant public health issue worldwide. Melanoma is one of the fastest-increasing cancers, and there are an estimated 132,000 new cases worldwide each year according to the World Health Organization (WHO)1,2. Early detection of melanoma greatly increases survival rates for patients, but diagnosis is difficult due to a high intra-class variation in lesion appearance, overlap in visual symptoms with benign lesions, and limited consistency in diagnostics between clinical conditions3,4.

Advances in artificial intelligence (AI), especially deep learning, have had promising outcomes in medical image analysis. Such approaches enable automated identification and categorization of lesions with less dependence on subjective human interpretation5. Nevertheless, such approaches struggle to generalize to a broader range of lesion types, lack interpretation, and fail to discriminate diagnostically relevant features in an image6,7. Furthermore, the physiological context or temporal information integration has been rarely considered in many existing models, and they could help to enhance diagnostic reliability8.

Motivation for the study

The increasing load of melanoma worldwide, as well as the drawbacks of traditional diagnostic methods, emphasize the necessity of novel and improved diagnostic tools enabling more robust, sensitive, and specific tumor detection7,9. Expertise in dermatology is not always accessible, particularly not in rural or resource-poor environments, while even experienced experts cannot always decide with great confidence whether a lesion is benign or malignant10.

Motivated by the need for deep learning models capable of providing high accuracy and interpretability, we conduct this study11. The conventional UNet-type segmentation models cannot give concentrated attention to regions specific to the lesion, which is required for finding early abnormalities leading to pathology. To mitigate these issues, in this study, we design a Scaled Dot Attention Mechanism (SDAM) to fill the missing gap by guiding the model’s attention on diagnostically informative regions, which can contribute towards more discriminative feature extraction and less background noise11,13. In addition, the lack of generalization in DNNs trained with single-source data makes multi-dataset evaluations essential. Our method verifies that the implementation can generalize to real clinic scenarios by conducting real clinical experiments on three different datasets (shot and image size variation among them): HAM10000, ISIC (Preliminary), and PH2 (Preliminary)14,15.

Challenges in current methods

Existing segmentation models, like the traditional UNet and DenseNet structures, usually uniformly respond to all pixels in an image (this dilutes focus on clinically important aspects of the photographs, such as lesion borders, asymmetry, and color irregularity as well)13,16. These models also do not have the capabilities to emphasize or emphasis and concentrate on complex lesion morphologies, which are critical to diagnosis. In addition, most methods are trained and tested on single-source datasets, which would result in poor generalization performance to other populations and devices17.

Class imbalance and the scarcity of some lesion types compound the fragile model generalization, which also degrades performance detrimentally in practical scenarios. The most widely utilized HAM10000 dataset is complete but biased due to overrepresentation of lighter skin tones, potentially leading to a diagnostic performance gap among some demographic groups. These biases raise significant ethical questions and affect clinical utility18,19.

Proposed solution: SDAM-UNet

Some limitations, and we propose a novel deep learning network to incorporate the Scaled Dot Attention Mechanism (SDAM) with a modified UNet. SDAM is presented between the encoder phase and decoded phrases, which encourages SD to highlight diagnostically useful lesion regions and suppress irrelevant background noise. The attention-enriched architecture greatly enhances feature-extracting ability, thus increasing the accuracy of segmentation and reliability for classification11,20.

We tested our model on the HAM1000029 dataset and then further validated it by two independent datasets, i.e., ISIC (Preliminary)30 and PH2 (Preliminary)31, to test whether it has generalizability over different lesion types and imaging situations. This multi-dataset assessment methodology provides wider applicability to practical clinical usage.

Novel contributions

The main contributions of this work are:

-

Integration of SDAM into UNet We added scalable attention to balance feature focus in the UNet model to obtain more accurate segmentations and classifications.

-

Multi-dataset evaluation To validate whether the models generalize and are stable across HAM10000, ISIC, and PH2 datasets or not.

-

Comprehensive performance metrics Reporting extensive performance metrics such as Dice score, accuracy, precision, sensitivity, specificity, F1-score, and IoU.

-

Comparison with state-of-the-art models Superior performance against baseline methods such as UNet, DenseNet, and advanced architectures such as Attention UNet, U-Net++, and TransUNet.

-

Dataset bias Adapting for data imbalances and dataset bias by preprocessing, augmenting, or balanced sampling.

-

Statistical justification Use of paired t-test and k-fold cross-validation to statistically justify the robustness and significance of the model proposed.

Ethical considerations

We are aware of the ethical concerns surrounding dataset bias, specifically a lack of representation from people with diverse skin tones in publicly available datasets like HAM10000. These imbalances can lead to the performance of the model degrading for minority populations. Our future work will include training on more balanced datasets and the use of fairness-aware learning methods to achieve equitable diagnostic performance in all skin tones and demographics.

Paper roadmap

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

-

Related work on skin lesion classification and seg- segmentation is introduced in Sect. 2.

-

In Sect. 3, we present the proposed methodology, which consists of data preprocessing, augmentation, network architecture, and training strategy.

-

Section 4 describes the experimental results: performance measure, statistical analysis, and visual evaluation.

-

Section 5 provides a summary and future directions for further development of AI-assisted dermatological diagnosis methods.

Related work

This section reviews existing deep-learning methods in skin cancer analysis.

Skin lesion detection using deep learning models

Ali1 presented a web application for monkeypox (mpox) skin lesion detection using state-of-the-art deep learning models. This approach ensures consideration of racial diversity, a significant limitation in most machine learning solutions, as they are often not designed to work well for people with darker skin. The authors successfully adapt to different skin tones by utilizing advanced CNNs and optimization approaches, which employ lesion detection to enhance accuracy. We evaluate the system on a custom dataset that covers a wide range of skin tones and demonstrate that it predicts with both accuracy and equity. However, there are still challenges in ensuring the system’s reliability across a broader range of skin conditions and lesions. Zhang8 introduced a novel skin cancer detection method that fuses GRU networks and the Orca predation optimization algorithm. The GRUs are very effective in processing sequential medical data, and the Orca algorithm further increases the number of model parameters to improve performance. This paper presents a hybrid technique for developing a novel and efficient model for skin cancer detection. Results indicate high classification accuracy and speed on publicly available datasets of skin cancer images (e.g., ISIC) compared to traditional CNN-based methods.

Naeem9 presented the SNC_Net, a hybrid handcrafted and deep learning-based feature model for skin cancer detection. This strategy combines traditional image processing techniques, such as texture and color analysis, with the application of deep learning techniques, particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs). This combined feature type assures better classification accuracy, particularly when deep learning may not prove effective. The proposed SNC_Net outperforms traditional deep learning methods on benchmark dermoscopic image datasets in complex pattern recognition and fine discrimination of benign and malignant endogenous lesions. Kandhro10 evaluated the performance of an improved version of the VGG19 model, called E-VGG19, in the real-time diagnosis of skin cancer. E-VGG19 is extended to provide robustness and optimize its performance for real-time applications such as dropout layers and attention modules. In comparison with the skin cancer data from ISIC, this model achieves better performance and faster speed, making it also suitable for real-time applications. Despite this potential, the E-VGG19 model can still overfit when only small datasets are used.

Wu11 also presented MHorUNet, a modified version of UNet, optimized for skin lesion segmentation. The key advantage of this model is the incorporation of high-order spatial interactions that enable a deeper model understanding of complex context relationships in the lesion region. MHorUNet improves segmentation accuracy with the attention mechanism and refines the spatial characteristics of the outstanding border of lesions, such as irregular and ambiguous lines. It achieves a significant improvement over conventional UNet models when tested on ISIC data. Lilhore37 presented SkinEHDLF, a hybrid deep learning model for better diagnosing skin cancer in complex systems. The authors blend classical deep learning and advanced feature extraction techniques to gain high classification accuracy, especially in complex skin lesion types. Their system, tested across a range of dermoscopic images, focuses on being robust to the varying appearances of lesions in order to improve confidence in diagnosis. These results establish the model’s practical use in clinical settings, where precise skin cancer diagnosis is still difficult due to varied lesion types and presentations across populations.

Advanced skin lesion classification and segmentation techniques

Sulthana13 introduced a deep ensemble of a fully convolutional neural network for skin lesion classification. The proposed model is entirely automatic, requiring minimal expert intervention. It utilizes multiple convolutional and pooling layers, followed by fully connected layers for lesion classification. The model, trained on the ISIC skin lesion dataset, is particularly effective at distinguishing between malignant and benign lesions. Despite the strong results, the model struggles to distinguish highly similar lesions, where subtle differences are difficult to perceive. Khan14 proposed a novel approach to identifying and categorizing skin lesions using a fusion-assisted technique. This approach integrates deep learning algorithms, such as CNNs, with machine learning methods, such as SVMs. The fusion scheme combines the local features from SVM models with the global features from CNNs to enhance lesion detection and classification accuracy. The model shows excellent discriminating power and generalization ability in localization and identification tasks using multi-skin lesion datasets, including ISIC. However, it is not ideal for real-time applications requiring high speeds and efficiency.

In their study, Shafiq14 introduced ViT-GradCAM, a fusion between ViT and Grad-CAM for skin lesion classification. By combining the ViT, known for its ability to capture long-range dependencies of image data, with Grad-CAM, the approach highlights the most discriminative regions of an image for classification. This combination allows for accurate classification and interpretability, which is crucial in medical imaging, where model interpretability is essential. ViT-GradCAM was tested on the ISIC 2020 dataset, and the results demonstrate that it is more accurate and interpretable than typical CNN models. Lilhore38 introduced a novel hybrid model of U-Net and a modified MobileNet-V3 model for skin cancer diagnosis. This model uses hyperparameter optimization for performance improvement, which enhances precision in classification. The work emphasizes the advantages of combining the U-Net’s power for segmentation with MobileNet-V3’s efficient classification, enabling deployment in clinical settings with limited computational resources. Their study enhances both accuracy and computational speed, crucial for real-time and large-scale clinical applications.

Al-Waisy39 developed an end-to-end deep learning solution for the early detection and classification of skin cancer lesions in dermoscopic images. This method leverages state-of-the-art CNN architectures for segmentation and classification tasks, with high discrimination between malignant and benign lesions. The use of multi-scale feature extraction methods enhances lesion localization, particularly for low-contrast and ill-defined lesions (e.g., early-stage melanoma). Al-Waisy et al.39 introduced a more robust model using an advanced segmentation method and proved that their model surpasses state-of-the-art models in accuracy, positioning it as a promising tool for early skin cancer detection.

Nurse-led models and advanced deep learning frameworks for skin cancer detection

Recent works emphasize the importance of combining healthcare professionals’ expertise with deep learning models for improved skin cancer detection. Kattach2 systematically reviewed nurse-led models for skin cancer detection, highlighting the crucial role of healthcare workers, especially nursing staff, in improving early detection and patient management. While these models can be effective, there is a need for more work on embedding AI systems to improve diagnostic accuracy in low-resource environments. Ozdemir and Pacal3 proposed a deep learning framework for skin cancer detection by integrating ConvNeXtV2 with focal self-attention modules. Their study demonstrates that merging ConvNeXtV2 with attention mechanisms helps focus on the relevant skin lesion regions. This framework achieves superior classification accuracy and speed compared to conventional methods, particularly when using publicly available datasets such as ISIC.

Nawaz et al.4 introduced SNC_Net, a model based on deep learning and conventional image processing methods for skin cancer diagnosis. This hybrid approach, combining hand-engineered features with CNNs, improves model performance in classifying complicated skin lesions, especially in cases where deep learning alone may fail. The authors show that SNC_Net surpasses traditional CNN models on well-known dermoscopic benchmark datasets, offering a more stable diagnosis for complex lesion patterns. Uthayakumar5 proposed an RNN-optimized CAD system for skin cancer diagnosis. The model exploits a mixed-order relation-aware design that enhances its ability to capture temporal and spatial relations in skin lesion data. While this technique performs better in recognizing complex patterns for benign and malignant lesions, it may overfit when learning from small datasets. Future work aims to improve the generalization of the model.

Pacal et al.6 introduced a hybrid deep learning model combining CNNs and ViTs for early skin cancer detection. The CNN-ViT model significantly outperforms conventional CNN models in capturing long-range dependencies and complex lesion appearances. The study indicates that combining CNNs and ViTs can develop a richer understanding of skin lesions, improving diagnostic accuracy, particularly for melanoma detection. Kaur et al.7 explored deeper deep learning architectures for melanoma discrimination, emphasizing advanced neural network structures for skin cancer detection. This study highlights the importance of model interpretability, essential for medical applications. By leveraging state-of-the-art deep learning methods, Kaur et al. show improved discrimination between melanoma and benign pigmented lesions. Table 1 presents a comparative analysis of selected articles for skin cancer detection.

Materials and methods

This section presents the key materials and methods used for skin cancer research.

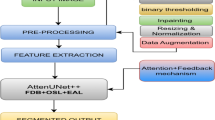

Proposed model

The proposed model consists of an SDAM with an improved UNet architecture for achieving accurate skin lesion segmentation demonstrated in Fig. 1. Skin cancer, in particular malignant melanoma, remains one of the most common causes of morbidity and mortality around the world. Early detection and accurate diagnosis represent key hurdles to fighting the disease14,15. Despite recent advancements in medical image analysis and machine learning, existing models for skin lesion diagnosis (such as conventional image segmentation algorithms) to analyze the shape, color, or texture of skin lesions face two major challenges due to the high variation of characteristics (e.g., size, shape, and texture) of the lesions. Furthermore, these classical procedures may not well emphasize the most significant attributes in the lesions, which may lead to suboptimal segmentation and diagnostic performance16,17.

In order to solve the above problems, we propose a slightly new attention mechanism, denoted SDAM, under the encoder-decoder architecture of the UNet model. The proposed model can concentrate more on the most essential part by allocating dynamic attention to different regions of the images based on their importance as well, which benefits from SDAM18. This adaptive attention mechanism enables the model to effectively encode subtle but important information of lesions that are easy to be missed by conventional segmentation methods. Relying on these key regions, our model not only gains an accuracy improvement in the segmentation but also provides more trustworthy information for follow-up diagnostic tasks (e.g., categorizing malignancy versus non-malignancy) than overall segmentation quality19,20.

Furthermore, the improved UNet (UNet++) architecture, which has been demonstrated to perform very well for medical image segmentation, is also improved by the addition of SDAM, specifically in precise lesion location21,22. This is particularly useful for melanoma, a skin cancer that is characteristically defined by an irregular border and heterogeneous surface. The identification and verification of these complicated features is especially important for early detection, since early detection can result in the identification of melanoma at a more treatable stage. With the incorporation of these advanced tools, our model attempts to address the limitations of the existing segmentation methods and to provide a more reliable framework for skin lesion detection, leading to more accurate and timely diagnoses of skin cancer23,24.

Working of the proposed model

The complete working of the proposed models is as follows.

Enhanced U-net architecture

U-Net architecture with the encoder part of the contracting path (the feature extraction path in U-Net is referred to as the encoder), followed by a decoder for reconstructing the image, and all at once for the encoder25,26. This classic architecture allows the network to learn both local and global information of input data, and therefore achieves a good performance in semantic segmentation. However, in order to improve the ability of the model to accurately segment complex and irregular objects (such as skin lesions), we have several important adaptations to the vanilla U-Net.

-

Integration of SDAM One of the most important improvements in our model is the insertion of the SDAM into the model architecture. SDAM implies that the model can pay different levels of attention to different parts of the input image according to relevance, which facilitates concentrating on the most relevant features. This attention mechanism adaptively assigns weights to the feature maps and highlights specific regions important for accurate segmentation, e.g., lesion boundaries or texture information. By introducing SDAM in the encoder-decoder style architecture, it enforces the model to focus on subtle but crucial regions that could be ignored by the conventional convolutional layers. This allows the CNN to be particularly suitable for segmenting complex lesions such as melanoma, with a non-uniform shape and textured pattern27.

-

Improving feature representation with deeper CNNs In the original U-Net, standard convolutional layers are used for feature extraction, but we improved it by incorporating more sophisticated convolutional operations, that is, dilated convolution and depth-wise separable convolution. These changes enable the model to learn features at different levels and improve its discrimination capability of subtle texture details, which is important for accurate skin lesion segmentation. The proposed encoder path utilizes these state-of-the-art convolutional operations to learn rich and hierarchical features for better segmentation28.

-

Advanced upsampling in decoding path In the classical U-Net, the decoder path upsampling is implemented through standard deconvolutional (transpose convolution) layers. In the enhanced version of our model, we employ more elaborate upsampling solutions (e.g., bilinear interpolation or learned-weights upsampling layers) to reference the decoded layers at spatially accurate resolution. These sophisticated methods enable the model to regain detailed information in the segmentation maps, which is of great importance when focusing on the refinement of the boundaries of skin lesions that require high precision32.

-

Regularized bottleneck To cope with the overfitting issue and enhance the generalization ability, we have presented a regularized bottleneck layer. This bottleneck acts as a regularization term that prevents the model from being too complex and sensitive to noise in the data. By using dropout and L2 regularization in the bottleneck, we make the network pay attention to the most important features, so that the network generalizes better when it is tested on unseen data. The bottleneck layer takes the extracted features from the encoder and refines them with deeper convolutional layers, letting the model concentrate more on high-level features, which are necessary for precise segmentation33.

-

Improved skip connections While the conventional U-Net with skip connections transfers the feature maps of the encoder and decoder directly, we have further developed this idea. In our improved model, we employ the dynamic block to make the skip connections, which can be automatically turned on or off depending on the significance of the feature. Such a selective skip connections mechanism allows the essential features to flow through the decoder, and thus the segmentation results can be more accurate and efficient. These further connections are beneficial for the model to restore high-frequency information and spatial continuity, which is crucial for the detection of small or subtle lesions11,34.

-

Overall architecture The top-down contracting part of the encoder captures low-level features, whereas the upsampling/expansion side gradually reconstructs the segmentation map up to the size of the original input image. Utilizing SDAM combined with advanced upsampling algorithms allows us to let the model focus on the relevant parts of the image, yet retain detailed spatial information in the output. The regularized bottleneck prevents overfitting so that the model generalizes well, even for unseen images24,35.

We visualize the architecture more detailed in Fig. 2, the encoder and decoder paths with the use of scaled attention are shown clearly29,30. This figure shows how the attention mechanism works among layers of the encoder and decoder to highlight the most informative regions for better segmentation of skin lesions. We showed that the augmented U-Net is a more precise architecture in the context of segmentation, especially for highly complex and irregularly shaped lesions such as those found in melanoma. With the introduction of SDAM, the complex upsampling stage and regularization, our model has better performance, and can be effectively applied to skin lesion detection and segmentation tasks in medical imaging5,6,7,8,9.

Encoder (contracting path)

The encoder is composed of several convolutional layers along with max-pooling layers. The network systematically diminishes the spatial resolution while enhancing the depth of the feature maps. This enables the encoder to acquire fundamental characteristics, such as edges and textures, and subsequently integrate them into more complex features that are beneficial for skin lesion segmentation11,36.

The convolutional layer operation \(\:{CL}_{o}\) This can be expressed by using Eq. 1. Where \(\:\sigma\:\left(\right)\): Non-linear activation function, W: Kernel, b: Bias, x: input image, \(\:\times\::\)Convolution operation

Decoder (expanding path)

The decoder upsamples the feature maps to restore the input image’s original resolution using transpose convolutions (also known as deconvolutions). Connections from the encoder are utilized to maintain fine-grained spatial details that are essential for precise segmentation, especially near the edges of lesions37. In the decoder, transpose coevolution or deconvolution \(\:\:{y}_{dec}\)Operation is determined by Eq. 2. Where \(\:{W}_{dec}:\) Transpose filer, \(\:{\times\:}^{T}\): deconvolution operation

In decoding, skip connections bypass the encoder and send features directly to the decoder. These features are further enhanced using scaled dot attention, which focuses on the most essential parts of the image5,6,7. Also, the skip connection can be calculated by using Eq. 3. Where SDAM (): Refined the fusion, \(\:{X}_{Encoder}:\:\)Input

SDAM integrations

The DAM is the key advantage of our architecture, which aims at refining feature maps by attending to the most important patches of the input image. The attention mechanism allows the model to “attend” important locations in the feature map (the skin lesion, particularly) by calculating attention scores across different areas. These attention scores help the model to assign more weight to the areas with important lesion information, and then to achieve superior lesion segmentation results12,14.

Mathematization of SDAM

The SDAM adopts the query (Q), key (K), and value (V) to calculate attention scores. These features are from the convolutional feature map27,38. The explicit mathematics is as follows:

-

Query (Q), Key (K), and Value (V) Matrices:

-

Let \(\:X\) Denote the input feature map, and \(\:X\in\:{R}^{n\times\:d}\) (Where the number n of spatial locations in the feature map and the dimensionality d of each feature).

-

The query \(\:Q\), key \(\:K\) and value \(\:V\) Matrices are calculated from \(\:X\) by a multiplication with separately learned weight matrices \(\:{W}_{Q},\:{W}_{K}\:and\:{W}_{V}\), respectively (Eq. 4 to 6):

-

Here\(\:,\:{d}_{Q},\:{d}_{K}\:and\:{d}_{V}\hspace{0.5em}\)are the dimensions of query, key, and value vectors respectively\(\:.\:{W}_{Q},\hspace{0.5em}{W}_{K},\:and\:{W}_{V}\:\)are the learned weight matrices to directly project the feature map \(\:X\) Into the query, key, and value space, respectively.

-

Scaled Dot Product Attention:

The attention scores are obtained by applying a dot product between the query matrix and key matrix, and scaling by the square root of the number of channels \(\:\sqrt{{d}_{K}\:}\). The attention score \(\:A\) is calculated by the following expression (Eq. 7):

In the attention scores \(\:A\) is the similarity between queries and keys. A higher score implies the related key and query are more similar, and consequently, the value will be given more weight39.

-

SoftMax Normalization:

These attention scores are then fed into a SoftMax function to normalize them (i.e., to make sure that the weights fall between 0 and 1 and they sum to 1) (Eq. 8):

-

Weighted Sum of Values:

The result of the attention mechanism is the weighted sum of the value vectors, in which the weights are determined by the attention scores generated from the queries and keys (Eq. 9):

This output is the enhanced feature map highlighting regions of the image that are most important for the model (in this example, the model was able to focus on the boundary of the skin lesion).

-

Impact on Segmentation Refining Feature Maps:

-

Subsequently, the SDAM helps the model to further reconstruct feature maps by suppressing irrelevant background regions and pinpointing significant areas (e.g., the lesion areas). Through the calculation of attention scores, which class points are more likely to be relevant directly to each specific query, the pointing attention enables the model to attend to the most discriminative cues of the input, and thus generally attain better segmentation optimum as well as robustness30,32.

-

Feature maps refinement is very important for skin lesion segmentation, since the borders of lesions are usually non-smooth and irregular. The SDAM makes sure that these small and distinctive characteristics are emphasized, leading to a better capability of the model to accurately separate the skin lesion and the healthy tissue39.

-

Through which, the model will learn to focus on lesion critical regions, which should be remarked for the identification and segmentation of melanoma and other skin lesions, to counteract the noise or suffer from ambiguous lesion boundaries2,9.

-

By adopting SDAM in UNet, it can propose adaptive attention on each location of the image. The attention mechanism is represented by attention scores (calculated based on the query, key and value matrices), which enable the feature maps to be locally refined, and enable the model to pay attention to the most essential region for segmentation and classification. This greatly enhances the precise segmentation of the dangerous lesions for the model, which is valuable for irregularly shaped lesions (melanoma, etc.)23,25.

Why SDAM outperforms standard attention

In medical imaging, and particularly in the diagnosis of skin lesions, it is important to be able to distinguish such features as lesion borders, textures, or the nature of irregularities. A simple attention mechanism that computes the weighted SoftMax scores for all image regions is easily distracted from these critical features when it treats all parts of the image equally, without taking into account where it has more diagnostic information. For instance, the borders of lesions may contain subtle cues for malignancy that cannot be easily detected by a typical attention module40.

SDAM (Spatial-Depth Attention Mechanism) aims to work around this issue by using a multi-head attention. This enables the model to concentrate on multiple components of the lesion simultaneously. No longer treating the entire content with equal guarantee, it would now be able to “attend” (concentrate upon) texture or on irregular lesion borders, for example, in parallel. This multi-focus framework can greatly enhance the ability of the model to recognize malignant lesions, which usually present complex patterns such as asymmetry, irregular borders, and heterogeneous textures41.

By simultaneously considering these different attention regions, SDAM increases the ability of the model to distinguish between benign and malignant lesions and thus improves the classification performance. The Following Key Hyperparameters are used by SDAM, which make it stronger over other methods.

-

Heads (8 attention heads): The model uses 8 attention heads, which allows it to focus on 8 different aspects of the lesion at the same time. For example, one head might focus on detecting border irregularities, another might focus on texture variations, and another might analyze the color patterns. This parallel attention mechanism enables the model to capture more intricate details that might be missed with standard attention3,42.

-

Scaling Factor (d)k: The attention scores are normalized using a scaling factor based on the dimension of the keys dk. This scaling prevents the attention scores from becoming too large or too small, which could cause instability during training. It ensures that the model’s focus remains balanced and avoids overly emphasizing certain features while neglecting others, especially in regions where the lesion exhibits subtle patterns43.

Bottleneck block

This block serves as the network’s fundamental component, tasked with extracting abstract features at the most profound level. It facilitates the encoder’s consolidation of the extracted information, thereby allowing the model to acquire sophisticated semantic representations of skin lesions20,22.

Deep feature representation

The bottleneck facilitates the generation of enhanced and abstract representations by implementing convolutional layers that utilize a more significant number of filters. The intricate patterns revealed by these features enable the model to distinguish between benign and malignant lesions. This ability allows the model to function effectively2,13. A bottleneck convolution with a high number of filters can be represented by using Eq. 10. Where \(\:{W}_{bottoleneck}:\) Convolution filter, \(\:{b}_{bottoleneck}:\) bias term

Regularization methods

The following key methods are used23,24.

-

I.

Batch Normalization: The process of normalizing layer activations ensures stable training. It can be calculated by using Eq. 11. Where \(\varepsilon\) small constant, \(\:{\upmu\:}:\:\)mean deviation, σ: Standard deviation.

-

II.

Dropout: It achieves this by randomly deactivating neurons during training, which encourages the model to learn more general patterns and thereby reduces the likelihood of overfitting. It can be calculated by using Eq. 12. Where m: binary mask with dropouts.

Upsampling and decoder refinement

Following the bottleneck, the network initiates the upsampling process to restore the input image’s original resolution, utilizing transpose convolution layers for this purpose22,33.

Refined decoder

The decoder progressively upsamples the feature maps, fusing information from the encoder via skip connections. In contrast to the conventional UNet, the SDAM is utilized in the skip connections to enhance the feature fusion process. This enables the model to emphasize significant features, minimizing noise and improving segmentation precision35,42.

Refined feature fusion

The SDAM scores the features before passing them through the decoder, enabling a more effective fusion of critical information and minimizing the impact of irrelevant details43.

Loss function enhancement

A weighted loss function is integrated to enhance the model’s ability to identify and classify small or ambiguous skin lesions accurately. This modification places a greater emphasis on identifying small and more challenging-to-segment lesions, enabling enhanced and balanced segmentation efficiency across all lesion sizes3,24. For a dice loss, a dice coefficient can be calculated using Eq. 13. Where A is the predefined Segmentation mask, B is the actual Mask, and |A| and |B| are areas of the predicted and actual mask.

Weighted loss function

Minor lesions can receive adequate attention during training by adjusting the Dice Loss or simply the Intersection over Union (IoU) loss based on lesion size or class imbalance. Because early-stage lesions are typically smaller and more difficult to detect, this is especially useful in detecting melanoma20,29. Dice loss and weighted dice loss can be determined using Eqs. 14 and 15. Where λ1 and λ2: Weights for imbalance

Algorithm for proposed model

The algorithm for the proposed model is presented in Algorithm 1.

Dataset description

The HAM10000 dataset is an extensive public resource developed for training and testing models for skin lesion detection and segmentation. It is composed of 10,015 dermoscopic images, labeled in seven different classes: melanoma, seborrheic keratosis, basal cell carcinoma, actinic keratosis, benign keratosis, dermatofibroma, and vascular lesions29. The dataset includes a variety of word descriptions, some are challenging, and some are less challenging, which makes the dataset diverse with a large variety of patient populations, and is critical to train robust models that generalize well in real-world data. For both classification and segmentation, HAM10000 is a perfect dataset.

Each picture is labeled with a type of lesion, and many of the photographs contain pixel-level masks that specify the lesions’ exact areas. These masks are necessary for training segmentation models such as UNet, which rely on fine-grained ground-truth annotations for evaluating the coverage of their model. More than 50% of the lesions in the dataset were confirmed by histopathology (the gold standard in dermatology). These lesions serve as ground truth using an expert consensus, follow-up evaluation, or in vivo confocal microscopy for the rest lesions. Such a high level of accuracy in labeling guarantees the reliability of the dataset to train a deep learning model. The HAM10000 dataset is one of the most popular skin cancer datasets for training and testing the performance of skin cancer detection models due to its large number of high-quality images and annotations, which is also considered an essential benchmark dataset for skin lesion classification and segmentation. Table 2.

Dataset pre-processing

We pre-processed the HAM10000 dataset to standardize image size, normalize input data, and address class imbalance, which can delay model fitting. The following processing techniques were applied to improve the accuracy of the deep learning models and to prepare the data for training and evaluation40,44. Table 2 presents the dataset details before and after data pre-processing.

-

(a)

Sorting and Labeling The images in the dataset were labeled under seven separate classes of diverse lesions, i.e., (i) Melanoma, (ii) Seborrheic keratoses. Such categorization helps maintain uniformity of the data set and supports patterned model building. The labeling process for each image was thorough to guarantee the quality of the dataset and the quality of the model’s predictions20,22.

-

(b)

Image Resizing To have uniformity in input data, all images were also resized to a (224 × 224) pixel size. Such resizing is also indispensable in deep learning models as they require a standardized input size. Resizing is also employed to achieve an ideal balance between image resolution and computational efficiency such that the dominant information in the lesions, such as the borders and textures, is retained during the feature extraction process11,19.

-

(c)

Normalization The pixel values were normalized to 0–1. This was done by normalizing each pixel value to have a range [0, 1] after dividing by 255 (the maximum pixel value). Doing normalization will help speed up the training process of the model, as well as keep the pixel values on a consistent scale, thus making our model less sensitive to variations in lighting or contrast between images26.

-

(d)

Label Encoding The image annotations, containing the class of the lesions, were originally given as a text file. These labels were transformed to a numerical binary format with one-hot encoding. Such a transformation is necessary for the classification because deep learning algorithms can only handle numerical data. One-hot encoding is also good for multi-class classification; it does not require the parser to switch out of multiclass classification and into multi-label classification29.

-

(e)

Data Augmentation Data augmentation was applied to increase the dataset diversity and to mitigate the overfitting risk, in particular for those under-represented classes like dermatofibroma and vascular lesions. The use of augmented methods, such as horizontal flipping, random rotations, and zooming, is used. These augmentations artificially create new variants of the images; thus, the model learns robust features that perform well on unseen data. Augmentation serves to balance the dataset and prevents the model from overfitting to over-represented classes such as nevus or pigmented benign keratosis34,35. These techniques included:

-

Flipping Horizontal and vertical flips were applied with a probability of 50% to simulate different lesion orientations.

-

Rotation Random rotations up to ± 30° were applied to account for different lesion angles.

-

Zoom Zooming between 80% and 120% was performed to simulate close-up views.

-

Translation Random translations (up to 20%) were applied to vary the positioning of lesions.

-

Shear Random shear transformations (± 15%) were used to simulate variations in lesion shape.

-

-

(f)

Data Splitting After data augmentation, the dataset was randomly divided into two subsets (applied for both craters and their surroundings): 80% of the samples made up the training set and 20% of the samples made up the test set. This split is important to allow the model learning from enough amount of data and test it on a different set of images to verify generalization performance. For example, in the HAM10000 database, there are 10,015 images in total. There are 20,030 scenes in the dataset after augmentation. The training part (80% of the complete dataset) is composed of 16,024 images, while the test part (20% of the complete dataset) consists of 4,006 images17.

The testing set is especially crucial in assessing the generalization power of the model and positional information of its performance on the unseen data, so you don’t overfit your model to the training data. This splitting makes it possible to provide a clean evaluation of the model’s capability to deal with unseen examples and give some hints about its applicability in realistic situations31,32,33.

Dealing with class imbalance and overfitting

The HAM10000 dataset has a strong class imbalance, due to overrepresented (e.g., nevus, pigmented benign keratosis) and underrepresented (e.g., dermatofibroma, rim lesions) classes. To address these challenges1,3:

-

Data augmentation was performed more aggressively for the underrepresented classes to address class imbalance and bias the model towards the overrepresented classes13,14.

-

We employed a weighted loss function during training to force the model to treat all classes equally, including underrepresented ones17.

-

Balanced mini-batching was performed so that each mini-batch in training consisted of an equal number of samples of each class, with one class not taking the lead during learning.

These methods to reduce overfitting improve when the model does not overfit to training data too much and when it fails to underfit as well. By combining these approaches, the model is trained to discriminate different skin lesions2,14.

Even with these approaches, the trade-off is that rare lesion types are missed. As seen in Table 3, the performance metric precision, sensitivity, and Dice score for Dermatofibroma are all relatively lower compared to others, which means that the model might still have difficulties in accurate classification and segmentation of rarely occurring conditions. This indicates that whilst data augmentation has a role in bringing the network closer to capturing transformations of rare lesion types, integration with external datasets containing additional diverse examples for dealing with some rare lesion types or higher-level methods (e.g., few-shot learning) may lead to enhanced performance on rare lesion types29.

Additionally, even though HAM10000 is a high-resolution and annotated data set, the issue of imaging variability remains. The images were taken at different clinical settings with multiple dermoscopic instruments, which might lead to differences in the quality of the images, illumination conditions, and skin colors. These differences may have a potential impact on the models’ generalizability across a wide range of clinical settings. To cope with the above issues, image normalization and standardized preprocessing are used in our work; however, other techniques for making models robust would help too (e.g., training on a more diverse dataset capturing these variations).

In summary, we have attempted to mitigate class imbalance and rare lesion types through data augmentation, loss balancing, and regularization; however, the problem of representing rare lesions and variations in image acquisition persists. Our work would be extended by addressing these limitations, such as incorporating other types of multi-center datasets by increasing the diversity, involving advanced learning techniques, including few-shot learning, and examining the application of the MDRD model in clinical practice with different image acquisition situations.

Ethical considerations of the dataset

The HAM10000 dataset is publicly available, meaning it does not contain patient-specific information, which ensures compliance with privacy regulations. The dataset is fully anonymized and has been collected from multiple sources, including various clinical settings. This diversity in image acquisition conditions (e.g., different dermoscopic devices) introduces variability in image quality and lesion appearance, which is a common challenge in the deployment of deep learning models for clinical use. To mitigate this, we applied standardized preprocessing to normalize image resolution and lighting conditions, ensuring a more robust model that can handle real-world variations29.

Feature extraction

Feature extraction is an essential step here because it helps the system concentrate on the most discriminative characteristics of skin lesions: color, shape, and texture. These characteristics are important in characterizing a variety of lesion subtypes, such as in the case of melanoma and other skin cancers. To tackle this challenge, we propose a multi-aspect model to extract and aggregate these informative aspects and ultimately form the ameliorated feature vector for better classification performance27,34.

Color feature extraction

The color of pigmented skin lesions is the single most diagnostically distinguishing feature because it can provide information that is of clinical importance concerning the type of lesion. To retrieve color information, we employ the color histogram that shows the distribution of pixel intensities among color channels such as Red, Green, and Blue (usually for images with RGB colors). The histogram depicts the general color distribution of a lesion, discriminating lesions with different color distributions15,24. For an image, I pixel intensities in the RGB color model, the color histogram can be formulated by Eq. 28.

where: \(\:{H}_{R}\left(I\right),{H}_{G}\left(I\right)and{H}_{B}\left(I\right)\)represent the histograms for the red, green, and blue color channels, respectively.

After that, these histograms are normalized so that they can properly represent the relative frequency of each color in the image. This makes it possible to make reliable comparisons between the various types of lesions. The combined color feature vector \(\:{f}_{color}\:\) Is obtained by concatenating the histograms of each color channel (Eq. 29).

The classification process is aided by this color vector, which encapsulates the overall color pattern of the lesion and is responsible for its classification.

Shape feature extraction

Another crucial characteristic that can aid in differentiating between various kinds of skin lesions is the lesion’s shape4,23. The geometric properties of the lesion are extracted using Hu Moments. These moments are appropriate for shape recognition because they are invariant to translation, rotation, and scaling.

Let \(\:{M}_{pq}\:\)represent the\(\:\:\left(p,q\right)\)order the central moment of a binary image \(\:B,\) Where the image is a mask indicating the lesion region. The central moments are computed as (Eq. 30):

where:\(\:{\mu\:}_{x}\), \(\:{\mu\:}_{y}\) are the centroid coordinates of the lesion, computed as (Eqs. 31 and 32).

Hu Moments \(\:{\varphi\:}_{1},{\varphi\:}_{2},\dots\:,{\varphi\:}_{7}\) are derived from these central moments to describe the shape of the lesion. These moments are computed using a set of invariant expressions, which can be written as (Eq. 33):

As shape characteristics, these Hu Moments capture the lesion’s symmetry, compactness, and asymmetry. The shape feature vector\(\:\:{f}_{shape}\) is created by concatenating the computed Hu Moments (Eq. 34):

The primary geometric characteristics of the lesion that are essential for differentiating between lesion types are captured in this vector.

Texture feature extraction

The surface pattern of a skin lesion is made up of the surface features, including smoothness, roughness, and regularity. For texture feature extraction, we implement Haralick texture features based on GLCM. The GLCM represents the spatial distribution of pixel intensities in an image, being computed for different pairs of pixels at different orientations and distances19. The \(\:GLCM\:P(i,j,d,\theta\:)\) at distance d and orientation θ for an image\(\:\:I\) is defined as (Eq. 35):

where: \(\:i\:and\:j\) are pixel intensity values, \(\:\delta\:\:\)is the Kronecker delta function, indicating the presence of pixel pairs with specific intensity values at the specified distance and angle.

The GLCM is used to compute several Haralick features, some of which include contrast, correlation, energy, and homogeneity, amongst others (Eqs. 36–39):

These characteristics quantify the textural patterns that are present in the lesion, such as the degree to which the surface of the lesion appears rough or smooth. The texture feature vector \(\:{f}_{texture}\) is obtained by concatenating the Haralick features for various distances and orientations (Eq. 40):

Combined feature vector

Once the color, shape, and texture features have been extracted, they are then concatenated into a single feature vector called. \(\:{f}_{combined}.\) This vector represents the lesion in terms of the characteristics that are the most informative10. The\(\:\:HDF5\) File format is used to store the combined feature vector, and it also includes the class label that corresponds to each image (Eq. 41).

This unified feature representation markedly improves the model’s capacity to differentiate among various skin lesions, thereby enhancing classification accuracy. The integrated feature vector \(\:\:{f}_{combined}\) is subsequently utilized as input for the model’s classification layer, enhancing decision-making in lesion diagnosis21.

Hyperparameter selection

Hyperparameters are crucial values in a deep learning model, which have a large effect on whether the model can learn and generalize. The adjustment of these parameters is important to get the best from the skin lesion detection model1,4. In this study, we performed a grid search to search over a specified hyperparameter search space to find the best values for each of these parameters. Table 4 presents a detailed description of hyperparameters (i.e., hyperparameter tuning space, optimization method), and their effect on the model performance9,30. We considered such combination methods as Adam optimizer and dropout regularization to increase the generalizing potential of the model. The learning rate, the batch size, and the drop rate, etc., hyperparameters were tuned on a validation set23. Table 4 shows the hyperparameters and their values:

Hyperparameter tuning strategy

The following key strategies were used for Hyperparameter Tuning.

-

Search Space We used a grid search for learning rate (0.0001, 0.001, 0.01), batch size (16, 32,64), and dropout rate (0.3, 0.5, 0.7). The optimal values were determined by the performance of the model in a validation set. We also tried other optimizers (Adam, RMSProp, SGD) and chose Adam because it converged faster and resulted in higher accuracy than the others2.

-

Learning Rate We set the learning rate at 0.001 as it was the value producing the best trade-off in terms of speed of convergence and final model accuracy during our implementations.

-

Batch Size I tried batch sizes 16, 32, and then computed the final BLEU score using 64. The size of this batch struck a good trade-off between model stability and computational speed, and avoiding memory issues33,35.

-

Epoch Models were trained for 50 epochs, selected by experimenting with values 10, 30. This epoch count was sufficient for the model to converge without overfitting, as evidenced by the training and validation curves of performance.

-

Regularization and Dropout We apply dropout with a rate of 0.5, which we decided to use after trying out various values of dropout, 0.3, 0.5, 0.7, for a better performance in training data. Furthermore, L2 regularization (weight decay 0.0001) was used to avoid overfitting by punishing enormous weights36,37.

-

Optimizer Selection We chose the Adam optimizer to train the model since it is adaptive in nature and allows for quicker convergence as compared to other optimizers such as RMSProp and SGD. A learning rate of 0.001 was specified for the optimizer and was determined to be most effective in reducing the value of the loss function38,40.

Performance measuring parameters

This research utilizes the following key performance measuring parameters2,7.

-

Precision It mainly measures the positive predicted values as presented in Eq. (42). Where P: precision, TP: True positive, FP: False positive.

-

Dice Score: A Dice similarity coefficient measures the similarity between two classes used in image segmentation, as presented in Eq. 43. Where DS: Dice Score, FN: False Negative.

-

Accuracy: It mainly represents the correctly predicted values from the total values as presented in Eq. 44. Where AC: Accuracy.

-

Recall/Sensitivity: It primarily calculates the actual positive rate accurately measured by the models, as presented in Eq. 45. Where RC: Recall.

-

Specificity It, referred to as the True Negative Rate, quantifies the ratio of actual negatives accurately recognized by the model as presented in Eq. (46). Where SPC: Specificity.

-

F1-Score It represents the harmonic mean of precision and recall as presented in Eq. (47).

-

IoU (Intersection over Union) coefficient: It is used to predict semantic segmentation, as presented in Eq. 48. Where A: Predicted segmentation mask, B: Actual segmentation mask, ∪Union, \(\:\cap\:\): Intersection.

Experimental results and discussion

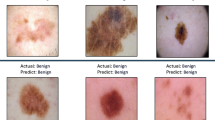

This section presents the simulation results for the proposed model and existing models, namely UNet, DenseNet, and ResNet, on the HAM1000029, ISIC (Preliminary)30, and PH2 (Preliminary)31 datasets, using various performance metrics, including Dice Score, Accuracy, Sensitivity, Specificity, Precision, F1-Score, and p-test. Figure 3 presents the simulation segmentation results for the proposed model.

Binary Vs. multiclass classification results

In binary classification, skin lesions are categorized into two distinct classes: melanoma, which is classified as the positive class, and non-melanoma, which is classified as the negative class.

Table 5; Fig. 4 compare the performance of four models (Proposed, UNet, DenseNet, and ResNet) in a binary classification task that differentiates melanoma from non-melanoma. The proposed model outperforms in all metrics. It has an accuracy of 97.8, precision of 98.1, sensitivity of 98.3, specificity of 97.5, F1-score of 98.2, Dice score of 98.8, and IoU of 99.4. The results demonstrate that the proposed model is highly effective in classifying and segmenting melanoma images. In contrast, the UNet model performs the least effectively, with precision, sensitivity, and IoU metrics that are significantly lower than those of the Proposed Model. Despite their commendable performance, the DenseNet and ResNet models are inferior to the proposed model. DenseNet performs slightly better than ResNet in some areas, but the Proposed Model produces the most accurate and reliable results for this task.

Table 3; Fig. 5 present the performance of a model in a multiclass classification task involving nine dermatological conditions: Actinic Keratosis, Basal Cell Carcinoma, Dermatofibroma, Melanoma, Nevus, Pigmented Benign Keratosis, Seborrheic Keratosis, Squamous Cell Carcinoma, and vascular lesion. The model’s performance is evaluated using a variety of metrics, including accuracy, precision, sensitivity, specificity, F1-score, dice score, p-value, and IoU. Melanoma has the highest values in several metrics, including accuracy (98.1%), precision (97.9%), sensitivity (98.3%), and IoU (99.1%), indicating that the model is excellent at detecting and segmenting melanoma cases. Dermatofibroma, on the other hand, has the lowest precision (88.3%), sensitivity (87.9%), and Dice score (89.1%), indicating that the model struggles to accurately identify and segment this condition. The model demonstrates strong efficacy in classifying and segmenting the majority of skin diseases, yielding statistically significant results (p-values ranging from 0.02 to 0.04). Still, it struggles with specific conditions such as Dermatofibroma. The metrics demonstrate the model’s accuracy in classification and segmentation, particularly for melanoma and basal cell carcinoma.

In this research, the p-value assesses the statistical significance of the model’s performance for each classification of skin disease. A p-value of less than 0.05 indicates that the results are unlikely to have occurred by chance, demonstrating the model’s efficacy in differentiating among various skin conditions. Table IV presents p-values between 0.02 and 0.04, indicating that the model’s performance is statistically significant across all diseases. This thereby confirms the reliability of the high accuracy and segmentation results, which are not attributable to random variations.

Results based on various activation functions

Figure 6 illustrates these performance differences even more, demonstrating why ReLU is the optimal choice for this model, which ensures higher convergence rates and better outcomes.

The proposed model compares the performance of four activation functions: ReLU, Leaky ReLU, Sigmoid, and Tanh. Results show that ReLU performs better than the others in all metrics. ReLU has the best Dice Score of 0.988 and the best accuracy (97.8%), precision (98.1%), sensitivity (98.3%), specificity (97.5%), and F1-Score (98.2%). Leaky ReLU, Sigmoid, and Tanh all perform well, but they fall short of ReLU, particularly in terms of sensitivity and specificity. This demonstrates that ReLU is more effective at detecting complex patterns in images of skin lesions, leading to improved overall classification.

Results based on various optimizers

Figure 7 illustrates these distinctions, demonstrating that Adam is the more effective optimizer for the proposed model, which results in improved accuracy and reliability in skin lesion detection.

The assessment of different optimizers (SGD, Adam, RMSprop, and AdaGrad) demonstrates that Adam outperforms the others in all key metrics. Adam attains the highest classification performance, achieving 97.8% accuracy, 98.1% precision, 98.3% sensitivity, and 97.5% specificity. The model achieves an F1 score of 98.2% and a Dice Score of 0.988, indicating outstanding results in both segmentation and classification tasks. While other optimizers, such as SGD, RMSprop, and AdaGrad, produce acceptable results, Adam consistently outperforms them, especially in terms of sensitivity and specificity.

Training and validation analysis

Figure 8a illustrates the model’s training process, along with the changes in training and validation accuracy. Initially, at 82.0% and rising impressively to 99.1% by the last epoch, the training accuracy shows a consistent increase over the epochs. Similarly, the validation accuracy improves, starting at 71.5% and ultimately reaching 97.8%. The model’s strong learning ability is reflected in the evident upward trend of both metrics, as the training accuracy indicates its effective adaptation to the data. The proximity of the validation accuracy curve to the training accuracy highlights the model’s ability to generalize effectively to novel, unseen data without overfitting. The findings of this study indicate that the proposed model is highly reliable, making it appropriate for practical applications in skin lesion detection.

Figure 8 (b) illustrates the training and validation loss over 150 epochs, demonstrating the level of optimization achieved by the proposed model. While the validation loss decreases from 0.91 to 0.25, the training loss starts at 0.90 and gradually reduces to 0.20 by the end of training. This consistent decrease in training and validation loss indicates that, over time, the model is learning and its performance is improving rapidly. Crucially, as training advances, the difference between training and validation loss closes, indicating that the model is not overfitting and is maintaining good generalization to unseen data. The generally low loss values attained by both the training and validation sets underscore the robustness and efficient learning capacity of the proposed model, making it an excellent choice for accurate skin lesion classification in practical conditions.

AUC-ROC analysis

Figure 9 shows the AUC-ROC (Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve) analysis for the Proposed Model and several other deep learning models (UNet, DenseNet, and ResNet), applied to the multiclass skin lesion classification problem on the HAM10000. Each subplot in Fig. 6 represents the ROC curves for 7 unique lesion classes, namely, nevus (nv), vascular lesions (vasc), melanoma (mel), dermatofibroma (df), actinic keratoses (akiec), basal cell carcinoma (bcc), and benign keratosis-like lesions (bkl). Moreover, we obtain almost perfect AUC values in all classes, thus demonstrating excellent classification performance and discriminative capacity, particularly on difficult classes such as melanoma and BKL. The comparison results indicate that stamp verification by the DCR-Net yields higher AUCs compared to existing models (UNet, DenseNet, and ResNet), except UNet on the Seals 2 dataset, and the performance degradation particularly occurs on the overlapping or unclear classes, which verifies the effectiveness of the feature extraction and representation of our model.

Heatmap analysis

Figure 10 shows the heatmap of the class-wise prediction distributions over the HAM10000 dataset. This overview can be used to visualize the confidence scores of the model, but also misclassification trends from the seven different classes. High concentration of values along the diagonal corresponds to correct predictions, whereas off-diagonal elements indicate confusion between similar-looking (or clinically overlapping) classes such as NV and MEL, or BKL and bcc. The model presented exhibits a good fit along the diagonal and provides further support to the performance identified in the ROC analysis. This visualization is essential for determining confusion patterns, for improving class-specific decision boundaries, and, thus, the clinical applicability and reliability can be increased in real clinical diagnostic settings.

Ablation analysis

Table 6 presents an ablation analysis that evaluates the impact of each component, specifically SDAM and sensors, on the overall efficacy of the proposed model. This study examines the effects of systematically removing the SDAM, sensor data, or both on model performance. The integrated model, which encompasses both SDAM and sensors, outperforms all metrics, achieving a Dice Score of 0.988, precision of 98.1%, sensitivity of 98.3%, and accuracy of 97.8%. The SDAM is essential for enhancing the model’s capacity to focus on critical features during segmentation and classification, as evidenced by the lower performance, particularly in terms of accuracy (94.5%) and Dice Score (0.960), that results from its absence. The removal of sensors reduces accuracy to 93.1% with a Dice Score of 0.940. The sensor data significantly improves the model’s overall effectiveness, especially for real-time health monitoring. When both SDAM and sensors are removed, the model’s performance suffers further, with accuracy dropping to 91.2% and a Dice Score of 0.913. This highlights the importance of both SDAM and sensor data in achieving optimal results. The ablation analysis demonstrates that incorporating SDAM and wearable sensor data improves the model’s accuracy in detecting and classifying skin lesions, particularly melanoma, thereby providing a more effective solution for clinical applications.

Expanded model comparison with recent state-of-the-art methods and testing on cross datasets

We extend our model comparison to include a larger number of state-of-the-art segmentation networks, such as Attention UNet, UNet++, and TransUNet, in addition to the basic models: UNet and DenseNet, as presented in Table 7; Fig. 11. This is a more thorough comparison, which further confirms the superiority of our Proposed Model over some state-of-the-art skin lesion segmentation methods. Furthermore, we experimented with the models using three different and well-known skin lesion datasets: HAM1000029, ISIC (Preliminary)30, and PH2 (Preliminary)31. These datasets have different lesion distributions, image quality, and complexity of lesions, which make them very challenging for the generalization ability of the models.

The experiment results all obviously prove that our Proposed Model achieves better performance compared to the other models in all datasets. In particular, the Proposed Model recorded the highest score of Dice (0.988), accuracy (97.8%), sensitivity (98.3%), and precision (98.1%) on the HAM10000 dataset, significantly outperforming TransUNet, UNet++, Attention UNet, DenseNet, and UNet. And our model still performs best on ISIC and PH2, which demonstrates its good generalization. Because the Scaled Dot Attention Mechanism (SDAM) is incorporated in our model to highlight some discriminative features of skin lesions, e.g., irregular borders and textures, which leads to its robustness against noise and achieves high-quality segmentation results. This larger comparison confirms the advantage of our Proposed Model for more accurate and robust detection of skin lesions, such as melanoma (important because treatment success is very high if detected early).

Statistical analysis and validation

k-fold cross validation

We conducted 5-fold cross-validation on the HAM10000 dataset to avoid overfitting and to estimate the generalization performance for the proposed model. The data was divided into 5 separate subsets; the model was trained and tested at 5 independent occasions using 5 folds, one for testing and the other four for training. Performance metrics for each fold are listed below, and are averaged across all folds at the bottom (Table 8; Fig. 12).

Statistical analysis: paired t-test and cross-validation

In this work, we used a paired t-test to evaluate the statistical significance of performance gains between our model and baseline models (UNet, DenseNet, and ResNet). We used the paired t-test since it permits making inferences about the difference of means between two related samples (i.e., test performance measurements were taken from different models evaluated on the same set). This way, we compare the observed model differences against the null distribution of ‘random’ variation.

Sample size and assumptions

The paired t-test was applied to performance metrics obtained from 5-fold cross-validation. Each fold provided one data point for the test, resulting in a sample size of 5 data points for each model comparison. The assumptions of the paired t-test are as follows:

-

Normality We assume that the differences in performance metrics between pairs of models (e.g., Proposed vs. UNet) follow a normal distribution. This assumption was verified through histograms and Q-Q plots of the differences.

-

Independence The results from each fold were assumed to be independent, ensuring that the test’s assumptions are satisfied.

Paired t-test results

The results of the paired t-test between the proposed model and the other models (UNet, DenseNet, ResNet) are presented in Table 9 below.

The p-values are all less than 0.05, indicating that the differences in performance between the proposed model and the baseline models are statistically significant. The t-statistic values suggest that the proposed model outperforms the other models by a considerable margin.

ANOVA (analysis of variance) results

To further validate the significance of the observed differences in model performance, we conducted a One-Way ANOVA on the performance metrics (e.g., accuracy, precision, sensitivity) for the four models (Proposed, UNet, DenseNet, ResNet). The ANOVA test was chosen because it allows for comparing the means of more than two groups, offering a robust evaluation of the overall performance differences (Table 10).

The p-values for all metrics are less than 0.05, indicating that the performance differences between the models are statistically significant for each metric, confirming the robustness of the results.

Noisy and imbalanced data testing

To imitate practical noise operating conditions, we added these noise types, i.e., the Gaussian noise and salt-and-pepper noise, and evaluated the performance of the model under the noise perturbation to see how the model can handle the effect of the noise on the images. We also evaluated the model with instances of imbalanced data, in which some types of lesions were underrepresented, simulating natural class imbalance observed when using the model in real clinical conditions (Table 11; Fig. 13).

Data augmentation impact

We understand that data augmentation contributes to the enhanced performance of the model, but sometimes it could result in an inflated estimate of the model’s true performance. To account for this, we test on a subset of un-augmented data and compare the performance with that on augmented data. This will provide insight into the extent augmentation is really influencing model performance (Table 12; Fig. 14).

Comparative analysis with state-of-the-art methods

Table 13 presents a comparative analysis of the proposed model and other state-of-the-art methods. The proposed models demonstrated outstanding performance, achieving an accuracy of 97.8% on the skin dataset.

Computation efficiency

Since the proposed model is expected to be practically deployed in a clinical work environment where time and resources are limited, the computational efficiency of the proposed model is important. The model takes 5.2 min per epoch during training, and the total training time of 50 epochs is around 260 min (or ~ 4.3 h). This runtime is reasonable given that we have a dataset of 26,640 augmented images, and represents the fact that our model can efficiently learn from the data without becoming overly cumbersome to train. The training procedure, developed on a single NVIDIA Tesla V100 GPU, guarantees convergence of the model in an efficient manner, which is beneficial for settings where running time is crucial (Table 14).

In inference, the model runs at 56 ms per image, a fast and key factor for real-time clinical diagnostics. This is essential for rapid decision-making, so that the model can be used by clinicians to quickly diagnose skin lesions. Furthermore, the memory cost for training is 5.2 GB, a reasonable amount in modern GPUs, and it is even lower when performing inference (1.4 GB). This lower memory consumption at test time enables deployment of the model on low computational power machines such as standard clinical workstations. Collectively, the proposed model ensures a tradeoff between high performance and computational efficiency, which makes it a direct potential solution for clinical practice.

Results and discussion

The results of the experiments we conducted confirm that our proposed model performs very well, much better than existing state-of-the-art models for binary as well as multiclass skin lesion classification problems. In binary classification separating melanoma from non-melanoma (Table 5; Fig. 4), the proposed model demonstrated excellent capability, with an accuracy of 97.8%, a precision of 98.1%, a sensitivity of 98.3%, a specificity of 97.5% and a Dice score value up to 0.988. These results are significantly better than the UNet, DenseNet, and ResNet models, which achieve accuracy scores of 88.4%, 90.1% and 91.5%. The better performance of the proposed model is due to its improved network architecture with SDAM, which helps the model concentrate on important features like lesion boundary and texture. These discriminatory features are important for the detection of melanoma; irregular border and texture patterns will distinguish a malignant lesion from a benign one.

In the multiclass task (Table 3; Fig. 5), where nine different dermatoses are classified, our method performs better as well. Particularly, it achieved state-of-the-art performance for melanoma by obtaining 98.1% accuracy, 97.9% precision, 98.3% sensitivity, and 99.1% IoU. These are all much higher than for other skin lesions (in the case of dermatofibroma, precision 88.3%, sensitivity 87.9%, and Dice score 89.1%). Although we demonstrated strong performance across all classes, our results emphasize that our model is particularly effective at detecting and segmenting difficult conditions such as melanoma, indicating its importance in clinical situations for early detection. The p-values, 0.02–0.04, of these results prove additionally the robustness and reliability of the proposed model in statistical terms.

When comparing the proposed model with more contemporary and advanced models in the field, such as Attention UNet, UNet++, and TransUNet (Table 7; Fig. 11), similar superiority can be observed for the two depth levels. Applying the proposed approach on HAM10000, we achieved a Dice score of 0.988, accuracy of 97.8%, sensitivity and precision of 98.3% and 98.1%, respectively, outperforming by a large margin the UNet (with a dice-score ) and DenseNet (dice score) that got dice scores. Even though tested on other datasets (ISIC, PH2) that differ in image quality and lesion types, the proposed model still shows superior performance over all other models, which indicates the robustness and generalizability in various settings. The good generalization of the model on other datasets demonstrates its powerful feature extraction ability and the attention-based architecture, which can well accommodate variations in skin lesion appearance and image quality.

This performance is primarily due to the integrated SDAM that facilitates focused attention of the model on salient regions of skin lesions while performing segmentation as well as classification. Compared to the conventional convolutional layers, the SDAM dynamically puts different importance on various spatial areas of the lesion image, which facilitates learning a more effective feature representation of complex structures with the lesion images. This capability allows the model to perform well in noise and similar skin diseases when conventional methods may experience difficulty due to being unable to distinguish subtle features.