Abstract

Medical image segmentation is a fundamental task in computer-aided diagnosis, playing a crucial role in organ structure analysis, lesion delineation, and treatment planning. However, current Transformer-based segmentation networks still face two major challenges. First, the global self-attention in the encoder often introduces redundant connections, leading to high computational cost and potential interference from irrelevant tokens. Second, the decoder shows limited capability in reconstructing fine-grained boundary structures, resulting in blurred segmentation contours. To address these issues, we proposed an efficient and accurate framework for general medical image segmentation. Specifically, in the encoder, we introduce a frequency-domain similarity measure and construct a Key-Semantic Dictionary (KSD) via amplitude spectrum cosine similarity. This enables stage-wise sparse attention matrices that reduce redundancy and enhance semantic relevance. In the decoder, we design a learnable gradient-based operator that injects boundary-aware logits bias into the attention mechanism, thereby improving structural detail recovery along object boundaries. On ACDC, the framework delivers a 0.55% gain in average Dice and a 14.6% reduction in HD over the second-best baseline. On ISIC 2018, it achieves increases of 1.01% in Dice and 0.21% in ACC over the second-best baseline, while using 88.8% fewer parameters than typical Transformer-based models. On Synapse, it surpasses the strongest prior approach by 1.03% in Dice and 6.35% in HD, yielding up to 8.36% Dice improvement and 52.46% HD reduction compared with widely adopted Transformer baselines. Comprehensive results confirm that the proposed frequency-domain sparse attention and learnable edge-guided decoding effectively balance segmentation accuracy, boundary fidelity, and computational cost. This framework not only suppresses redundant global correlations and enhances structural detail reconstruction, but is also robust to different medical imaging modalities, providing a lightweight and clinically applicable solution for high-precision medical image segmentation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Medical image segmentation is a cornerstone of computer-aided diagnosis, underpinning a wide spectrum of clinical tasks1. By providing accurate delineation of anatomical structures and pathological regions, segmentation yields quantitative and objective information that supports functional assessment, disease progression monitoring, and individualized treatment planning. For instance, in cardiac imaging, precise segmentation of the ventricles and myocardium is vital for reliable computation of functional indicators such as ejection fraction2,3. In oncology, robust tumor boundary delineation enables volumetric analysis, longitudinal follow-up, and radiotherapy target definition4. Similarly, in dermatology, accurate localization of skin lesions plays a critical role in early melanoma detection and population-level screening5. Consequently, both the precision and efficiency of segmentation models have a direct impact on clinical decision-making and therapeutic outcomes6.

The advent of deep learning has greatly advanced the development of automated medical image segmentation. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have dominated this field for years, achieving strong results on various public benchmarks7. Nonetheless, CNNs are inherently limited by their local receptive fields, which restrict their ability to capture long-range contextual information. This shortcoming makes them less effective for complex anatomical structures or ambiguous lesion boundaries. To overcome these limitations, Transformer architectures have recently been introduced into medical image analysis8. Benefiting from the global self-attention mechanism, Transformers can model long-range dependencies and integrate global contextual cues, thereby enhancing the segmentation of multi-scale and morphologically diverse structures. Transformer-based frameworks such as TransUNet9 and Swin-Unet10 have reported promising outcomes across multiple imaging modalities, including cardiac MRI, abdominal CT, and dermoscopic images.

Despite these encouraging results, Transformer-based segmentation networks continue to face two significant challenges. First, the encoder’s global self-attention requires the computation of a full token-to-token similarity matrix, which incurs quadratic complexity in both computation and memory usage11,12. This not only increases resource demands but also introduces redundant correlations that dilute semantic relevance and may incorporate irrelevant information. Second, while the decoder benefits from global context, it remains insufficient in reconstructing fine-grained boundary details, often producing blurry or inaccurate contours13,14. Such limitations are especially detrimental in clinical contexts where boundary precision is essential, such as differentiating subtle myocardial borders in cardiac imaging or outlining infiltrative tumor margins. These challenges hinder the efficiency, robustness, and broader clinical adoption of Transformer-based medical image segmentation methods15,16.

To overcome the aforementioned limitations, we proposed a general medical image segmentation framework that balances computational efficiency with segmentation accuracy. The framework introduces targeted improvements to both the encoder and the decoder, aiming to simultaneously reduce redundant computations and enhance boundary reconstruction.

In the encoder, we incorporate a frequency-domain similarity measurement strategy. Specifically, local feature representations are transformed into the frequency domain, where cosine similarity of the amplitude spectra is employed to evaluate the correlation between tokens. Based on these correlations, a Key-Semantic Sparse Dictionary Attention (KSSDA) mechanism is constructed, which retains only the most relevant token interactions within each stage. By replacing the dense global self-attention with stage-wise sparse attention matrices, KSSDA effectively suppresses irrelevant token interference and avoids the quadratic computational burden, thereby yielding more compact and efficient feature representations.

For the decoder, we design a Learnable Edge-Guided Decoding (LEGD) module. Unlike fixed filters such as Sobel or Prewitt, this operator is implemented with trainable convolutional kernels, enabling adaptive extraction of boundary responses from feature maps. The resulting boundary strength map is then integrated into the attention mechanism by injecting a logits bias, guiding the decoder to emphasize structural details along object boundaries. LEGD not only enhances sensitivity to complex boundary variations but also alleviates common issues such as contour blurring or boundary misalignment.

By combining KSSDA in the encoder with LEGD in the decoder, the proposed framework achieves a favorable trade-off between reduced computational complexity and improved segmentation accuracy, delivering both efficient feature extraction and high-quality boundary reconstruction. In summary, our contributions are twofold. First, the proposed frequency-domain KSSDA encoder reduces redundant global correlations and lowers attention complexity, offering more compact representations while improving Dice by 4–5% and reducing HD by over 7 mm in controlled ablation settings. Second, the LEGD decoder enhances boundary modeling through adaptive gradient-based cues, yielding up to average 3.6% Dice improvement and 3.1 mm HD reduction over fixed edge operators. When integrated into a unified architecture, these components enable consistent performance gains across ACDC, ISIC 2018, and Synapse, achieving average 8.1% higher Dice and up to 40.6% lower HD than recent Transformer-based baselines, while operating with a lightweight 11.8 M parameter design that is substantially smaller than typical Transformer counterparts.

Related work

CNN-based segmentation methods

Early approaches to medical image segmentation were predominantly based on CNN architectures, among which U-Net17 stands out as the most influential model. U-Net employs a symmetric encoder–decoder design with skip connections between corresponding layers, enabling the effective fusion of low-level spatial details and high-level semantic information. This architecture achieved groundbreaking success in two-dimensional medical image segmentation tasks. Building on this foundation, several variants of the U-shaped architecture have been proposed. V-Net18 extended U-Net into three dimensions by introducing 3D convolutions, allowing direct processing of volumetric data and demonstrating strong performance on MRI and CT segmentation. U-Net++19 enhanced multi-scale feature representation by introducing nested and dense skip pathways, yielding improved results in both organ and lesion segmentation. Attention U-Net20 incorporated attention gating modules into the decoder, enabling the model to focus adaptively on target regions, which is particularly beneficial for segmenting small organs or lesions. More recently, nnU-Net21 introduced a self-adaptive framework that automatically configures network depth, kernel size, and preprocessing strategies according to the characteristics of each dataset. Owing to its automation and strong generalization ability, nnU-Net has achieved state-of-the-art performance in multiple international medical image segmentation benchmarks and is widely regarded as a powerful baseline.

Despite the remarkable success of these U-shaped CNN models, their inherent reliance on local receptive fields limits their ability to capture long-range dependencies. As a result, CNN-based methods often struggle with complex anatomical structures and ambiguous boundaries22. These limitations have motivated the introduction of Transformer architectures into medical image segmentation, leveraging global self-attention mechanisms to compensate for the shortcomings of CNNs in modeling long-range contextual relationships23.

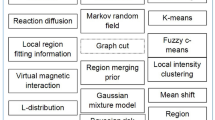

Transformer-based segmentation methods

To address the limitations of CNNs in modeling long-range dependencies, Transformer architectures have been increasingly adopted in medical image segmentation. A representative work, TransUNet9, integrates a CNN encoder with a Transformer module, thereby combining local feature extraction with global context modeling. Swin-Unet10 employs a hierarchical Swin Transformer24 to build a pure Transformer-based U-shaped architecture, achieving competitive performance across multiple modalities, including cardiac MRI, abdominal CT, and dermoscopic images. Furthermore, UNETR22 leverages a ViT as the encoder and incorporates skip connections to directly fuse Transformer features into the decoder, demonstrating strong performance in 3D segmentation tasks. Other approaches such as MedT25 and SwinBTS26 explore multi-scale or cross-modality designs, further improving the adaptability and effectiveness of Transformer-based segmentation frameworks.

More recent works have sought to balance accuracy and efficiency. MISSFormer27 introduces a lightweight multi-scale Transformer, preserving global modeling capability while reducing computational overhead. UCTransNet28 proposes a channel-interactive Transformer module to enhance semantic representation, particularly effective for small organ segmentation. DS-TransUNet29 incorporates a dual-scale Transformer design to improve adaptability to organs and lesions of different sizes. SwinFPN30 integrates hierarchical Swin Transformers with a feature pyramid network to strengthen cross-scale feature fusion. The latest UniverSeg31 framework extends Transformers toward universal medical image segmentation across diverse tasks and modalities, showcasing strong generalization ability. Collectively, these studies highlight the growing impact of Transformers in advancing medical image segmentation. Several works32,33,34 have further adapted Transformer-based frameworks to volumetric data, achieving efficient 3D segmentation and underscoring their versatility in medical imaging.

Attention methods

Although Transformers have demonstrated great potential in medical image segmentation, existing approaches still face notable limitations. In the encoder, global self-attention requires the computation of a full token-to-token similarity matrix, which incurs quadratic complexity in both computation and memory, leading to redundancy and irrelevant correlations that hinder efficiency and scalability. In the decoder, while global context is effectively modeled, the reconstruction of fine-grained boundary details remains insufficient, often resulting in blurry or shifted contours that are undesirable in clinical applications.

(1) Linear Attention Methods: The main idea is to approximate the self-attention mechanism and reduce the computational complexity from \(O({n^2})\)to \(O(kn)\), thereby enabling efficient modeling of long sequences. Representative examples include: Linformer35, which projects the Key and Value into a low-dimensional space via low-rank approximation, avoiding the need to construct the full similarity matrix and validating the low-rank property of attention; Performer36, which introduces orthogonal random feature maps to approximate the softmax kernel, reformulating attention into a linear form with unbiased estimation; Nyströmformer37, which applies the Nyström method to approximate the attention matrix using a subset of landmarks, reducing computational cost while preserving global structure; Linear Transformer38, which rewrites attention as an inner product of kernelized queries and keys, enabling efficient cumulative computation during inference; FlashAttention39, which unlike approximation-based methods, FlashAttention achieves exact attention computation with reduced memory footprint and latency by reordering memory access patterns and optimizing kernels. These methods have achieved notable success in NLP and computer vision and are now being increasingly adopted in medical image analysis to reduce computational burdens and improve scalability.

(2) Sparse Attention Methods: These approaches reduce complexity by enforcing sparsity in the attention connections while preserving global modeling capacity. For instance, Longformer40 employs a combination of local sliding windows and global tokens; BigBird41 integrates random, global, and block-local connections to balance efficiency and expressivity; Sparse Transformer42 accelerates sequence modeling via block-sparse patterns; and Reformer43 leverages reversible residual layers and locality-sensitive hashing (LSH) to reduce memory usage.

These efficient attention mechanisms provide practical alternatives to dense self-attention and have inspired follow-up research on designing lightweight and scalable Transformers for medical image segmentation.

Contribution

The main contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

(1) Frequency-domain sparse attention: The proposed Key-Semantic Sparse Dictionary Attention reduces redundant global correlations and lowers attention complexity while enhancing feature compactness. It improves average Dice by up to 0.55% and reduces HD by 14.6% over the second-best baseline, while requiring 88.8% fewer parameters than typical Transformer-based encoders.

(2) Learnable edge-guided decoding: The Learnable Edge-Guided Decoding module strengthens contour reconstruction through adaptive gradient-based boundary cues. It brings up to 1.03% Dice and 6.35% HD improvement over the strongest prior method, achieving as much as 8.36% Dice and 52.46% HD gains relative to widely adopted Transformer baselines.

Methodology

Data collection and processing

We conducted experiments on three publicly available datasets of different modalities, namely the Automated Cardiac Diagnosis Challenge (ACDC) dataset, the ISIC 2018 skin lesion segmentation dataset, and the Synapse multi-organ segmentation dataset. A detailed comparison of their characteristics is provided in Table 1. Specifically, Table 1 summarizes the key attributes of the datasets used in this study, including imaging sequences, data partitioning, annotated regions, image resolution, the number of classes, and imaging modalities.

ACDC: The ACDC dataset comprises 100 cardiac MRI scans acquired from different subjects, with imaging performed using cine-MRI (bSSFP) sequences. The dataset was divided into training, validation, and testing subsets in a 7:1:2 ratio. Specifically, the training set includes 70 cases (1,304 slices), the validation set contains 10 cases (182 slices), and the test set consists of 20 cases (370 slices), each accompanied by corresponding segmentation masks. Each MRI volume is composed of multiple two-dimensional slices, with annotations provided for three cardiac structures: the left ventricle (LV), the right ventricle (RV), and the myocardium (MYO). Each 2D slice has an in-plane resolution of approximately 216 × 256 pixels, and each MRI volume contains about 9 slices on average, with annotations for three cardiac structures and a single imaging modality.

ISIC 2018

The ISIC 2018 dataset is designed for skin lesion analysis, with images acquired through RGB dermoscopy. In total, 2,594 dermoscopic images are provided by the organizers. For our experiments, we allocated 1,815 images for training, 259 for validation, and 520 for testing. The annotations correspond to the skin lesion regions, and each image has a resolution of 600 × 450 pixels (RGB). The dataset contains one segmentation class and is based on a single imaging modality.

Synapse

The Synapse dataset consists of 30 contrast-enhanced abdominal CT scans, totaling 3,779 axial slices, provided by the MICCAI 2015 Multi-Atlas Abdominal Labeling Challenge. Each scan contains between 85 and 198 slices with an in-plane resolution of 512 × 512 pixels, and the voxel spacing is approximately 0.54 × 0.54 × (2.5–5.0) mm³. Annotations are available for eight abdominal organs, including the aorta, gallbladder (GB), left kidney (KL), right kidney (KR), liver, pancreas (PC), spleen (SP), and stomach (SM). The dataset involves 8 classes and a single imaging modality.

Network architecture

The overall framework of our method follows a typical encoder–decoder paradigm, where we make two targeted modifications to enhance both feature representation and boundary reconstruction, as illustrated in Fig. 1.

On the encoder side, we replace the conventional CNN backbone with a KSSDA Transformer to achieve efficient global feature modeling. Specifically, the input medical image is first partitioned into non-overlapping patches and embedded into a high-dimensional feature space, forming a sequence of tokens. These token sequences are then processed by the KSSDA Transformer. Unlike standard dense self-attention, KSSDA introduces a KSD that is constructed via amplitude spectrum cosine similarity within each stage. This dictionary selectively preserves only the most relevant token interactions, thereby suppressing redundant connections and reducing quadratic complexity. Moreover, the KSD is shared across all layers within each stage, ensuring consistent semantic modeling and yielding more compact and discriminative feature representations.

For the decoder, we design a LEGD module dedicated to recovering fine-grained boundary structures. Instead of relying on fixed gradient filters, LEGD employs Learnable Edge Filters, whose weights are initialized with classical Sobel and Scharr kernels to provide strong edge-detection priors at the early stage of training. During optimization, these filters are updated as trainable parameters, enabling adaptive extraction of boundary responses tailored to medical imaging data. The resulting edge strength maps are not only used as auxiliary boundary features but also injected into the attention mechanism as logits bias, explicitly guiding the decoder to emphasize boundary regions of organs and lesions.

By integrating KSSDA in the encoder for sparse and efficient feature extraction and LEGD in the decoder for boundary-aware refinement, the proposed architecture achieves a favorable balance between computational efficiency and segmentation accuracy, delivering precise structural delineation with enhanced boundary quality.

KSSDA transformer

In the preceding section, we described the overall network design. Here, we provide a detailed account of the proposed Key-Semantic Sparse Dictionary Attention Transformer, as illustrated in Fig. 2, which aims to reduce the computational burden of conventional self-attention while maintaining strong global modeling capability for medical image segmentation. Standard self-attention constructs a full pairwise similarity matrix of size \({{\mathbb{R}}^{n \times n}}\), requiring quadratic complexity \(O({n^2})\) in both computation and memory, where n is the number of tokens. When applied to high-resolution medical images, this quickly becomes a computational bottleneck. Furthermore, the dense matrix often encodes numerous redundant or irrelevant token interactions, which consume resources without contributing to meaningful representation learning. This motivates the development of a sparse mechanism that selectively preserves only the most semantically relevant dependencies.

To address this issue, we introduce a frequency-domain approach for token similarity estimation. Let the feature sequence at the -th stage be defined as in Eq. (1):

Each token vector \(f_{i}^{{(s)}}\) is transformed into the frequency domain using a one-dimensional Fourier transform, after which the normalized amplitude spectrum is obtained, as shown in Eq. (2):

The correlation between tokens is then measured by cosine similarity in the amplitude spectrum space in Eq. (3):

Compared with spatial-domain similarity, amplitude-based similarity is invariant to phase shifts and local misalignments, thus offering a more stable and robust measure of structural and textural relationships in medical images.

From the similarity matrix, each token retains only its top-k most relevant neighbors in Eq. (4):

This selection defines a KSD that serves as a sparse mask in Eq. (5):

The dictionary is shared across all layers and attention heads within a stage, ensuring semantic consistency and reducing redundant computations. With the KSD mask, attention computation no longer operates over all tokens. The conventional self-attention can be written as as Eq. (6):

where \(Q,K,V \in {{\mathbb{R}}^{{n_s} \times d}}\). In KSSDA, the operation becomes, as shown in Eq. (7):

with \({M^{(s)}} \in {\{ 0, - \infty \} ^{{n_s} \times {n_s}}}\) representing the mask derived from the dictionary. This ensures that only the top-k positions for each query participate in softmax normalization, while the remaining entries are effectively ignored. Equivalently, each queryi can directly gather its k neighbors in Eq. (8):

where \(\tilde {K}_{i}^{{(s,h)}},\tilde {V}_{i}^{{(s,h)}} \in {{\mathbb{R}}^{k \times {d_h}}}\). In this way, the normalization domain of softmax is explicitly reduced from \({n_s}\) to k.This sparsification leads to significant computational savings. The complexity of standard attention is \(O(H \cdot n_{s}^{2} \cdot {d_h}) \approx O(n_{s}^{2})\). while the proposed KSSDA reduces it to \(O(H \cdot {n_s} \cdot k \cdot {d_h})+O({n_s} \cdot {d_s} \cdot \log {d_s}) \approx O(k{n_s})\), where the second term corresponds to the Fourier transform required to build the dictionary. Since this cost is shared within a stage, its impact is minor. Importantly, because \(k \ll {n_s}\), the overall savings in both computation and memory are substantial.

LEGD module

To enhance the capability of the segmentation network in modeling boundary regions of medical images, we propose a LEGD module as shown in Fig. 3. In medical imaging, organ and lesion boundaries are often characterized by abrupt voxel intensity changes or discontinuous textures, making edge information particularly critical for accurate delineation. However, conventional Transformer decoders typically struggle to reconstruct fine-grained contours, resulting in blurred or shifted boundaries. To address this issue, LEGD introduces edge-aware bias into the attention mechanism, explicitly reinforcing structural boundary modeling and thereby improving reconstruction accuracy.

Unlike traditional edge detectors with fixed kernels, the convolution filters in LEGD are defined as trainable three-dimensional parameters. For initialization, they are assigned the weights of classical Sobel and Scharr operators, which are designed to extract gradient information along the x, y, and z directions. For example, the Sobel kernels are initialized as:

Similarly, the Scharr kernels are initialized as:

During training, these convolutional kernels are updated through backpropagation, enabling them to evolve from classical operators into adaptive filters specialized for medical imaging. The use of Sobel and Scharr for initialization leverages their complementary strengths: Sobel is robust to noise and effective for detecting low-contrast boundaries, while Scharr offers improved rotational invariance and sensitivity to structural details, which is advantageous for delineating irregular anatomical regions. This initialization allows the model to inherit useful priors while retaining adaptability during optimization, thereby improving its applicability across different modalities and organs. Extending the design into three dimensions further strengthens boundary modeling, where kernels in the x direction capture vertical gradients, those in the y direction highlight horizontal structures, and those in the z direction account for inter-slice variations, ensuring consistency and continuity in volumetric CT and MRI data.

Formally, given an input feature map \(F \in {{\mathbb{R}}^{n \times d}}\), the edge responses along the three axes are defined as shown in Eq. (9):

The directional responses obtained from the x, y, and z kernels provide complementary information about gradient variations along different spatial axes. To achieve a coherent representation of boundary strength, these components are combined into a single edge magnitude by aggregating their squared values. This fusion not only preserves directional sensitivity but also produces a rotation-invariant measure of edge intensity as shown in Eq. (10):

Followed by normalization to produce an edge strength map in Eq. (11):

This edge strength map is subsequently incorporated into the attention mechanism as a logits bias, imposing an explicit constraint on boundary-related regions during the computation of attention weights. As shown in Eq. (12), this bias term adjusts the attention distribution to emphasize edge-sensitive regions, thereby encouraging the model to capture fine structural variations more effectively. This design not only enhances the network’s responsiveness to complex and irregular boundaries but also alleviates the common issues of blurred or shifted contours observed in conventional decoders.

Through this design, the LEGD module integrates the advantages of Sobel and Scharr initialization with the adaptability of learnable filters, enabling stronger edge sensitivity. This approach preserves the global modeling capability of the decoder while significantly improving the precision and fidelity of reconstructed anatomical boundaries, particularly for complex structures in volumetric CT and MRI data.

Evaluation metrics and loss function

To comprehensively evaluate the segmentation performance on ACDC, ISIC 2018, and Synapse, we select a set of complementary metrics. Dice and mIoU are used to measure region overlap and global segmentation accuracy, while HD assesses boundary precision, which is crucial in clinical practice. For ISIC 2018, additional metrics including SE, SP, ACC, and Recall are reported to better reflect performance under class imbalance, ensuring both sensitivity to lesions and robustness against false positives. Together, these metrics provide a balanced evaluation of accuracy, boundary quality, and clinical reliability. To comprehensively assess segmentation performance, we adopt a set of complementary evaluation metrics that jointly capture region overlap, boundary precision, and class-level discriminability. The Dice coefficient is used to quantify the spatial overlap between the predicted mask and the ground truth, formulated as shown in Eq. (13):

where TP, FP, and FN denote true positives, false positives, and false negatives. To evaluate the accuracy of contour alignment, the Hausdorff Distance (HD) is employed, defined by Eq. (14):

where x and y are the ground-truth and predicted contours, and \(D( \cdot , \cdot )\) represents the Euclidean distance. For ISIC 2018, which involves lesion detection under class imbalance, we additionally report classification-oriented metrics. Sensitivity (SE) measures the ability to correctly identify positive samples in Eq. (15):

while Specificity (SP) evaluates the correct identification of negative samples in Eq. (16):

The overall Accuracy (ACC) is expressed as shown in Eq. (17):

Recall, which is equivalent to sensitivity in binary cases, is given by Eq. (18):

Finally, the mean Intersection over Union (mIoU) provides an average IoU score across categories in Eq. (19) :

where C is the total number of classes. Collectively, these metrics provide a comprehensive and balanced evaluation, covering regional overlap, contour fidelity, and classification reliability.

Since the ACDC, ISIC 2018, and Synapse datasets involve multi-label medical image segmentation tasks, we employ the Dice loss to guide the overall optimization of the network by enforcing region-level overlap consistency between predictions and ground truth. To further mitigate class imbalance across different categories, we incorporate the Binary Cross-Entropy (BCE) loss as an auxiliary term. The final combined objective is formulated in Eq. (20), which integrates both Dice and BCE components to achieve stable and balanced training.

Result

Implementation detail

Our model was implemented using PyTorch 2.0.1, and all experiments were carried out on a cloud computing platform equipped with four NVIDIA A100 GPUs. Throughout the training process, we employed the AdamW optimizer to update parameters, with the initial learning rate set to 1e-3, a weight decay of 1e-5, and the number of training epochs fixed at 500. In our experiments, we employed ITK-SNAP for result visualization, which can be freely obtained from the official website at https://www.itksnap.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php? n=Downloads.SNAP4.

ACDC dataset comparison experiment

To assess the segmentation capability of our proposed model, we first conducted experiments on the ACDC dataset. Under identical experimental settings, we further compared our method against six state-of-the-art medical image segmentation models, including TransUNet, MISSFormer, Swin-Unet, LeViT-Unet, MedFormer, and LaplacianFormer. All models were trained and evaluated using the same preprocessing pipeline, training configurations, and evaluation metrics, ensuring a fair and consistent comparison.

The quantitative results are summarized in Table 2, which reports the performance of our model against several representative segmentation approaches across multiple evaluation metrics, including mean Dice coefficient (Dice), mean Intersection-over-Union (mIoU), and Hausdorff Distance (HD). As shown, our method consistently achieves superior segmentation accuracy. Specifically, it attains Dice scores of 96.62 for the left ventricle (LV), 90.95 for the right ventricle (RV), and 90.03 for the myocardium (MYO), surpassing all competing methods. Notably, in the critical LV segmentation task, our model outperforms TransUNet, Swin-Unet, LeViT-Unet, and MedFormer by absolute Dice gains of 1.25%, 0.79%, 1.00%, and 1.12%, respectively, while also exceeding the LaplacianFormer by 0.88%. In terms of mIoU, our model achieves class-wise scores of 93.35 (LV), 89.05 (RV), and 84.69 (MYO), yielding an average of 89.03, further confirming its robustness across multiple cardiac structures.

(a) Short-axis view of a representative original MRI slice. (b) Expert manual segmentation result. (c–i) Visualization of the prediction results from seven segmentation models. The yellow rectangular box represents the areas where the segmentation model’s result image differs significantly from the standard label image.

In terms of boundary accuracy measured by the Hausdorff Distance (HD), our model demonstrates remarkable performance. For the segmentation of the left ventricle (LV), right ventricle (RV), and myocardium (MYO), the HD values achieved are 7.11 mm, 8.71 mm, and 9.55 mm, respectively. Compared with the state-of-the-art LaplacianFormer, which reports HD values of 8.43 mm, 9.98 mm, and 11.32 mm, our method reduces the error by 15.6%, 12.7%, and 15.6%, respectively. These results indicate that introducing the LEGD module into the decoder effectively handles challenging boundary regions. Overall, on the high-quality ACDC dataset, our approach delivers stronger segmentation performance than other leading methods.

Figure 4 presents the visual comparison of segmentation results on the ACDC dataset across our model and six competing methods. Specifically, (a) shows the short-axis view of a representative original MRI slice, (b) depicts the expert manual annotation, and (c–i) illustrate the predictions of the seven segmentation models. The yellow boxes highlight regions where the model outputs deviate from the ground-truth labels. As observed in Fig. 4, our method not only achieves substantial improvements in quantitative metrics but also delivers visually more precise segmentations, particularly along the boundaries of the myocardium and right ventricle. Comparative analysis of panels (c–i) further demonstrates that, in segmenting key cardiac anatomical structures, our model which integrating a sparse attention mechanism with a learnable edge-guided decoding module shows clear advantages in terms of regional consistency, boundary delineation, fine-grained detail recognition, and robustness against misclassification.

ISIC 2018 dataset comparison experiment

Table 3 reports the experimental results of our method compared with seven state-of-the-art models on the ISIC 2018 dataset. As shown, our model achieves scores of 92.90 (SE), 97.98 (SP), 84.32 (mIoU), 91.04 (Dice), and 96.26 (ACC), demonstrating strong robustness across different datasets. In particular, our method achieves a 0.37% relative improvement in mIoU, 1.73% in Dice, and 1.46% in ACC over the second-best MedFormer, further confirming its superior segmentation capability.

We further introduced the number of parameters as an additional evaluation metric to highlight the lightweight nature of our model. As shown in the Table 3, TransUNet has the largest parameter size, reaching 105 M, which makes it a considerably heavy architecture. In contrast, MedFormer (12.48 M) and BRAU-Net++ (14.39 M) can already be regarded as relatively compact designs. Remarkably, our model contains only 11.77 M parameters, the smallest among all compared approaches, approximately 1/9 of TransUNet, and even lower than many existing lightweight frameworks. Despite its extremely small parameter count, our method still surpasses mainstream models in key metrics such as mIoU, Dice, and ACC. This demonstrates that by constructing a semantic sparse dictionary in the frequency domain, our approach effectively reduces redundant connections and mitigates the interference of irrelevant tokens commonly encountered in global Self-Attention. These results confirm that our model achieves high segmentation accuracy while maintaining a lightweight architecture.

Among the compared approaches, the four models with the highest Dice scores are our model with a Dice of 91.04%, BRAU-Net + + reaching 90.03%, MedFormer achieving 89.49%, and Swin-UNet with 89.46%, as shown in Fig. 5. Although these architectures employ strong multi-scale designs or attention mechanisms, our method still delivers the highest segmentation accuracy. This improvement is largely attributed to the frequency-domain semantic sparse dictionary, which suppresses redundant token interactions and reduces background interference that frequently appears in dermoscopic images. As a result, the model extracts more discriminative lesion features and produces clearer and more stable boundary representations. Notably, the model reaches this performance with roughly twelve million parameters, significantly smaller than most lightweight competitors and less than one-ninth of the heaviest baseline. Despite its compact size, the method consistently outperforms mainstream models, demonstrating the effectiveness of the proposed sparse representation strategy.

Synapse dataset comparison experiment

To further validate the generalization ability of our model across different imaging modalities, we conducted not only performance evaluations on the ACDC and ISIC 2018 datasets, but also extensive comparative experiments on the Synapse multi-organ abdominal CT dataset. These experiments were designed to assess the robustness and accuracy of our method under diverse medical imaging scenarios.

The experimental results are summarized in Table 4, which compares our model with several representative segmentation methods across multiple evaluation metrics. Specifically, the table reports the overall Dice score and Hausdorff Distance (HD), as well as the Dice scores for individual organs, including the aorta, gallbladder, left and right kidneys, liver, pancreas, spleen, and stomach. As shown, our method achieves an average Dice of 84.54 and an HD of 14.59, representing an improvement of approximately 8.36% in Dice and a reduction of about 52.46% in HD compared with TransUNet. Notably, our approach obtains the lowest HD among all methods, indicating that it not only maintains high segmentation accuracy but also substantially enhances boundary consistency.

For several key organs, including the liver (95.83), spleen (92.86), and stomach (86.03), our model achieves the best or near-best segmentation accuracy. For more challenging organs such as the aorta and pancreas, although RWKV-Unet shows competitive performance with local advantages, our method still demonstrates superior overall performance in terms of both mean Dice and HD, further confirming its robustness in handling complex anatomical boundaries. Taken together, these results highlight that our method delivers a globally optimal balance, ensuring both high segmentation accuracy and stable performance across organs.

In addition, we compared the visualization results of the top four models, including (c) MISSFormer, (d) RWKV-Unet, (e) EMCAD and (f) Our Model, ranked by Dice score against the (a) Raw Data and (b) Ground Truth annotations, as illustrated in Fig. 6. The figure clearly shows that our method provides more accurate and continuous delineation of organ boundaries, particularly for challenging structures such as the pancreas and gallbladder, where it preserves structural integrity better than other high-performing models. These observations are consistent with the quantitative results in Table 4, where our approach achieves the best performance in terms of both mean Dice and HD, underscoring its superior robustness in segmenting complex multi-organ anatomical regions.

Ablation experiment

To evaluate the effectiveness of the KSSDA and LEGD modules, we conducted ablation studies on three datasets: the ACDC cardiac dataset, the ISIC 2018 skin lesion dataset, and the Synapse multi-organ abdominal dataset, with the results summarized in Tables 5 and 6, and 7.

As shown in Table 5, when employing Self-Attention or Linformer, the overall segmentation accuracy drops notably, with mean Dice scores of 85.56 and 86.53, and HD values of 22.16 mm and 12.78 mm, respectively. This indicates that under constrained computational budgets, Self-Attention and Linformer are limited in their ability to capture long-range dependencies, resulting in inferior segmentation performance. In contrast, incorporating the KSSDA module into the encoder significantly boosts Dice scores, particularly for the LV (95.25) and RV (88.72) regions. Furthermore, introducing the Learnable Edge-Guided Decoding (LEGD) module in the decoder notably improves boundary accuracy, as reflected by a substantial reduction in HD, achieving even lower values than the full model, which demonstrated the LEGD’s positive effect on boundary reconstruction and contour precision. While LEGD alone achieves a slightly lower HD, the full model yields the best overall balance across Dice and boundary metrics. The complete model achieves the best overall performance, with mean Dice of 92.53, and Dice scores of 96.62, 90.95, and 90.03 for LV, RV, and MYO, respectively, while reducing HD to 8.45 mm. These results highlight that the combination of spectral feature embedding and edge-guided mechanisms provides complementary advantages, enabling not only high segmentation accuracy but also improved boundary consistency.

From the ablation results on the ISIC 2018 dataset shown in Table 6, it can be observed that using conventional self-attention alone leads to a large parameter size (29.13 M) while yielding limited segmentation performance (Dice of only 84.09). When replacing it with Linformer, the parameter count decreases to 15.24 M, and the Dice score improves to 89.74, suggesting that linear attention offers a better trade-off between efficiency and accuracy. Incorporating the KSSDA module further reduces the parameter size to 9.06 M and enhances overall performance, achieving 87.41 of SE, 97.35 of SP, 88.24 of Dice, and 93.07 of ACC. Adding the LEGD module yields an additional Dice gain of approximately 7.27% compared with the fixed-operator setting, indicating that LEGD effectively strengthens boundary representation and alleviates mis-segmentation in ambiguous regions. By combining both KSSDA and LEGD, the complete model leverages their complementary strengths to jointly capture global semantics and local structural details in skin lesion segmentation. This integration of linear attention mechanisms with dynamic learning strategies not only enhances segmentation accuracy but also substantially reduces the overall parameter count.

The boundary heatmap comparisons in Fig. 7 provide clear evidence of the effectiveness of the proposed boundary-enhanced mechanism.

Specifically, Swin-UNet and MedFormer often produce diffuse or unstable boundary activations, indicating that their feature extractors struggle to localize fine-scale contour transitions. Although BRAUNet + + sharpens certain edge regions, its responses remain inconsistent and tend to break around irregular lesion shapes or low-contrast boundaries.In contrast, our model yields uniformly concentrated and structurally coherent boundary responses. The activation maps tightly adhere to the true lesion outline, capturing subtle curvature changes and avoiding the fragmented or noisy patterns observed in other models. This demonstrates that the integration of KSSDA and LEGD enables the network to effectively suppress irrelevant background signals while selectively enhancing edge-related tokens. Overall, the visual evidence confirms that the proposed boundary-aware modules not only strengthen contour representation but also improve robustness across diverse lesion types.

To further examine the contributions of the KSSDA and LEGD modules, we performed ablation studies on the Synapse dataset, with the results summarized in Table 7. Comparing Self-Attention, Linformer, and KSSDA, it can be observed that incorporating KSSDA achieves the most substantial parameter reduction, requiring only 9.04 M parameters, which is approximately 86.46% fewer than Self-Attention (66.80 M), highlighting the advantage of sparse attention. On the other hand, contrasting the Scharr operator with the LEGD module demonstrates that LEGD is particularly effective for boundary refinement, improving the Dice score to 82.98 and reducing HD to 16.03. As shown in Table 7, the complete model achieves the best overall performance, with 84.54 of Dice, 14.59 of HD, and only 11.91 M parameters, confirming the effectiveness of the proposed approach.

To further isolate the individual contributions of the KSSDA and LEGD modules, we conducted module-wise ablation experiments on both the ACDC and Synapse datasets, as summarized in Table 8. The baseline model without either component yields limited performance on both benchmarks. Introducing KSSDA alone provides substantial gains in global semantic modeling, improving Dice by 4.89% on ACDC and 5.42% on Synapse, while reducing HD by 6.87 mm and 6.98 mm, respectively. In contrast, enabling LEGD alone primarily strengthens boundary localization, improving HD by 13.21 mm on ACDC and 17.42 mm on Synapse. When both modules are combined, the full model achieves the highest accuracy across both datasets, with Dice scores of 92.53 on ACDC and 84.54 on Synapse, accompanied by the lowest HD values. These findings demonstrate that KSSDA and LEGD offer complementary benefits, KSSDA enhances long-range semantic dependencies, while LEGD refines boundary structures, jointly enabling substantial improvements in segmentation accuracy and contour precision.

As shown in Table 9, the proposed KSSDA module achieves a favorable balance between inference speed, training efficiency, and memory consumption. Compared with standard self-attention, KSSDA reduces inference time from 2.48 s/iter to 1.85 s/iter, decreases training time from 2.73 s/iter to 1.67 s/iter, and lowers memory usage by approximately 31%. Moreover, KSSDA provides competitive efficiency relative to other linear-attention variants such as Linformer, Performer, and Linear Transformer, while maintaining lower memory consumption than all of them. These results demonstrate that the sparsity-driven design of KSSDA effectively improves computational efficiency without sacrificing segmentation performance.

We further investigated the impact of the parameter k in the frequency-domain similarity–based sparse attention mechanism. Optimization experiments were conducted on the ACDC and Synapse datasets, with the results presented in Figs. 8 and 9.

Results in Figs. 8 and 9 are obtained from k-only ablations on validation folds, which may differ from the final test-set metrics reported in Tables 2 and 4.

We first conducted experiments on the ACDC dataset to determine the optimal value of k. As shown in Fig. 8, the best performance was achieved when k = n/3, yielding a Dice of 90.5. This suggests that at an optimal spectral dimension, the model effectively balances global and local feature representations, thereby improving region overlap. In contrast, when k = n/8 or k = n, the Dice drops significantly, indicating that excessive compression results in insufficient structural information, while over-expansion may introduce noise and redundant features, both of which degrade segmentation quality. On the Synapse dataset, the best result occurs at k = 2n/3, where the Dice reaches 89.5, suggesting that this dataset is more sensitive to mid-to-high dimensional spectral embeddings, and that moderately increasing the feature dimension can enhance the representation of complex abdominal structures.

The variation trend of HD95 is consistent with that of the Dice, further validating the findings. On the ACDC dataset, the lowest HD95 of 2.0 mm occurs when k = n/3, confirming that this spectral configuration also provides the most accurate boundary localization. Similarly, on the Synapse dataset, the HD95 reaches its minimum value of 2.0 mm at k = 2n/3, indicating that an appropriate choice of k benefits boundary delineation. In contrast, as illustrated in the Fig. 9, when k = n/8 or k = n, the HD95 values increase, suggesting that selecting k either smaller or larger than two-thirds compromises the robustness of boundary segmentation.

The two sets of experiments consistently demonstrate that selecting an appropriate range of k enables a better trade-off between regional consistency and boundary accuracy. The ACDC dataset tends to achieve optimal performance at moderate spectral dimensions, whereas the Synapse dataset benefits more from higher, yet not excessive, dimensional settings. These findings indicate that while different datasets vary in their sensitivity to spectral space scaling, the overall trend remains consistent: neither excessive compression nor full preservation of all features is desirable.

Summary

This study introduces a boundary-aware sparse Transformer architecture for medical image segmentation, aiming to overcome two persistent issues in existing Transformer-based models: the computational expense of dense global self-attention and the insufficient recovery of detailed boundaries. To address the first challenge, the encoder employs a Key-Semantic Sparse Dictionary Attention mechanism, where token correlations are computed in the frequency domain through amplitude spectrum cosine similarity, producing stage-wise sparse attention that reduces redundancy while maintaining semantic fidelity. For boundary refinement, the decoder integrates a Learnable Edge-Guided Decoding module, which utilizes trainable filters initialized from Sobel and Scharr operators to dynamically capture edge information. These edge features are injected into the attention process as bias, guiding more accurate contour reconstruction. Evaluations on three public datasets ACDC, ISIC 2018, and Synapse show that the proposed framework consistently improves segmentation accuracy and boundary quality, while also achieving substantial reductions in parameters and computational cost, underscoring its efficiency and generalizability across imaging modalities.

Data availability

The ACDC, ISIC 2018, and Synapse datasets are publicly available and can be accessed at https://www.creatis.insa-lyon.fr/Challenge/acdc/, https://challenge.isic-archive.com/data/, and https://www.synapse.org/, respectively.

References

Pinto-Coelho, L. How artificial intelligence is shaping medical imaging technology: a survey of innovations and applications. Bioengineering 10, 1435 (2023).

Bernard, O. et al. Deep learning techniques for automatic MRI cardiac multi-structures segmentation and diagnosis: is the problem solved? IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 37, 2514–2525 (2018).

El-Taraboulsi, J., Cabrera, C. P., Roney, C. & Aung, N. Deep neural network architectures for cardiac image segmentation. Artif. Intell. Life Sci. 4, 100083 (2023).

Tran, K. A. et al. Deep learning in cancer diagnosis, prognosis and treatment selection. Genome Med. 13, 152 (2021).

Codella, N. C. F. et al. Skin lesion analysis toward melanoma detection: a challenge at the 2017 International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI), hosted by the International Skin Imaging Collaboration (ISIC). IEEE 15th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI 2018), 168–172 (2018). (2018).

Wang, H. et al. A comprehensive survey on deep active learning in medical image analysis. Med. Image Anal. 95, 103201 (2024).

Yao, W. et al. From CNN to transformer: a review of medical image segmentation models. J. Imaging Inf. Med. 37, 1529–1547 (2024).

Dosovitskiy, A. An image is worth 16×16 words: transformers for image recognition at scale. Preprint at (2020). https://arxiv.org/abs/2010.11929

Chen, J. et al. TransUNet: Transformers make strong encoders for medical image segmentation. Preprint at (2021). https://arxiv.org/abs/2102.04306

Cao, H. et al. Swin-UNet: Unet-like pure transformer for medical image segmentation. Eur. Conf. Comput. Vis. 2022, 205–218 (2022).

Lin, X., Wang, Z., Yan, Z. & Yu, L. Revisiting self-attention in medical Transformers via dependency sparsification. Med. Image Comput. Computer-Assisted Intervention – MICCAI. 2024, 555–566 (2024).

Xing, Z., Ye, T., Yang, Y., Liu, G. & Zhu, L. SegMamba: long-range sequential modeling Mamba for 3D medical image segmentation. Proc. Med. Image Comput. Comput.-Assisted IntervMICCAI. 578–588 (2024). (2024).

Wu, Z. et al. TransRender: a transformer-based boundary rendering segmentation network for stroke lesions. Front. Neurosci. 17, 1259677 (2023).

Zhang, X. et al. SMTF: sparse transformer with multiscale contextual fusion for medical image segmentation. Biomed. Signal. Process. Control. 87, 105458 (2024).

Xing, Z., Yu, L., Wan, L., Han, T. & Zhu, L. NestedFormer: nested modality-aware transformer for brain tumor segmentation. Proc. Med. Image Comput. Comput.-Assisted IntervMICCAI. 140–150 (2022). (2022).

Xing, Z., Zhu, L., Yu, L., Xing, Z. & Wan, L. Hybrid masked image modeling for 3D medical image segmentation. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inf. 28, 2115–2125 (2024).

Ronneberger, O., Fischer, P. & Brox, T. U-Net: convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. Int. Conf. Med. Image Comput. Comput. -Assisted Interv (MICCAI 2015). 9351, 234–241 (2015).

Milletari, F. et al. V-Net: Fully convolutional neural networks for volumetric medical image segmentation. Proc. 2016 Fourth Int. Conf. 3D Vis. (3DV), 565–571 (2016).

Zhou, Z. et al. UNet++: a nested U-Net architecture for medical image segmentation. In Deep Learning in Medical Image Analysis and Multimodal Learning for Clinical Decision Support (DLMIA 2018 / ML-CDS 2018), Lecture Notes in Computer Science 11045, 3–11 (2018).

Oktay, O. et al. Attention U-Net: learning where to look for the pancreas. Preprint at (2018). https://arxiv.org/abs/1804.03999

Isensee, F. et al. nnU-Net: Self-adapting framework for U-Net-based medical image segmentation. Preprint at (2018). https://arxiv.org/abs/1809.10486

Hatamizadeh, A. et al. UNETR: transformers for 3D medical image segmentation. Proc. IEEE/CVF Winter Conf. Appl. Comput. Vis. (WACV), 574–584 (2022).

Shen, Z. et al. COTR: convolution in transformer network for end to end polyp detection. 7th International Conference on Computer and (ICCC), 1757–1761 (2021). (2021).

Liu, Z. et al. Swin Transformer: hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. Proc. IEEE/CVF Int. Conf. Computer Vision (ICCV), 10012–10022 (2021).

Valanarasu, J. M. J. et al. Medical transformer: gated axial-attention for medical image segmentation. Med. Image Comput. Comput. -Assisted Interv – MICCAI. 2021, 36–46 (2021).

Jiang, Y. et al. SwinBTS: a method for 3D multimodal brain tumor segmentation using Swin transformer. Brain Sci. 12, 797 (2022).

Huang, X., Deng, Z., Li, D. & Yuan, X. MISSFormer: an effective medical image segmentation transformer. Preprint at (2021). https://arxiv.org/abs/2109.07162

Wang, H. et al. UCTransNet: rethinking the skip connections in U-Net from a channel-wise perspective with transformer. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 36, 2441–2449 (2022).

Lin, A. et al. DS-TransUNet: dual Swin transformer U-Net for medical image segmentation. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 71, 1–15 (2022).

Wittmann, B. et al. MIDL. SwinFPN: leveraging vision transformers for 3D organs-at-risk detection. Medical Imaging with Deep Learning (2022). (2022).

Butoi, V. I. et al. ICCV. UniverSeg: universal medical image segmentation. Proc. IEEE/CVF Int. Conf. Computer Vision 21381–21394 (2023). (2023).

Zhou, H. Y. et al. nnFormer: interleaved transformer for volumetric segmentation. Preprint at (2021). https://arxiv.org/abs/2109.03201

Lan, L. et al. BRAU-Net++: U-shaped hybrid CNN-Transformer network for medical image segmentation. Preprint at (2024). https://arxiv.org/abs/2401.00722

Gao, Y. et al. A data-scalable transformer for medical image segmentation: architecture, model efficiency, and benchmark. Preprint at (2022). https://arxiv.org/abs/2203.00131

Wang, S. et al. Linformer: self-attention with linear complexity. Preprint at (2020). https://arxiv.org/abs/2006.04768

Choromanski, K. et al. Rethinking attention with Performers. Preprint at (2020). https://arxiv.org/abs/2009.14794

Xiong, Y. et al. Nyströmformer: a Nyström-based algorithm for approximating self-attention. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 35, 14138–14148 (2021).

Katharopoulos, A., Vyas, A., Pappas, N. & Fleuret, F. Transformers are RNNs: fast autoregressive transformers with linear attention. Proc. 37th Int. Conf. Mach. LearnICML. 5156–5165 (2020). (2020).

Dao, T., Fu, D. Y., Ermon, S., Rudra, A. & Ré, C. FlashAttention: fast and memory-efficient exact attention with IO-awareness. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 35, 16344–16359 (2022).

Beltagy, I., Peters, M. E. & Cohan, A. Longformer: the long-document transformer. Preprint at (2020). https://arxiv.org/abs/2004.05150

Zaheer, M. et al. BigBird: Transformers for longer sequences. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 33, 17283–17297 (2020).

Child, R., Gray, S., Radford, A. & Sutskever, I. Generating long sequences with sparse transformers. Preprint at (2019). https://arXiv.org/abs/1904.10509

Kitaev, N., Kaiser, Ł. & Levskaya, A. Reformer: the efficient transformer. Preprint at (2020). https://arxiv.org/abs/2001.04451

Xu, G. et al. LeViT-UNet: make faster encoders with transformer for medical image segmentation. Pattern Recognit. Comput. Vis. – PRCV 2023 (Lecture Notes in Computer Science), 42–53 (2023).

Azad, R. et al. MICCAI. Laplacian-Former: overcoming the limitations of vision transformers in local texture detection. Int. Conf. Med. Image Comput. Comput.-Assisted Interv. 736–746 (2023). (2023).

Wang, H. et al. Mixed Transformer U-Net for medical image segmentation. ICASSP 2022 IEEE Int. Conf. Acoustics, Speech & Signal Processing (ICASSP), 2390–2394 (2022).

Heidari, M. et al. WACV. HiFormer: hierarchical multi-scale representations using transformers for medical image segmentation. Proc. IEEE/CVF Winter Conf. Appl. Comput. Vis. 6202–6212 (2023). (2023).

Rahman, M. M. & Marculescu, R. Medical image segmentation via cascaded attention decoding. Proc. IEEE/CVF Winter Conf. Appl. Comput. VisWACV. 6222–6231 (2023). (2023).

Jiang, J. et al. RWKV-UNet: improving U-Net with long-range cooperation for effective medical image segmentation. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2501.08458 (2025).

Ruan, J., Li, J. & Xiang, S. VM-UNet: Vision Mamba UNet for Medical Image Segmentation. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2402.02491(2024).

Rahman, M. M., Munir, M. & Marculescu, R. EMCAD: efficient multi-scale convolutional attention decoding for medical image segmentation. Proc. IEEE/CVF Conf. Comput. Vis. Pattern RecognitCVPR. 11769–11779 (2024). (2024).

Funding

This research was supported by the Yancheng City Health Commission Medical Research Project (YK2024056), Yancheng Science and Technology Bureau - Yancheng Key Research & Development (Social Development) Program (YCBE202319, YCBE202456), Specialized Clinical Medicine Research Project of Nantong University (2024LQ027), The Special Funds for Science Development of the Clinical Teaching Hospitals of Jiangsu Vocational College of Medicine (20229167), College-local Collaborative Innovation Research Project of Jiangsu Medical College (202490127).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C. L.: Software, Methodology, Performed experiments, Writing—original draft preparation, review and editing, Visualization, Project administration. Q. L.: Investigation, Data curation and analysis, Software, Validation. J. S.: Guidance. All authors have discussed and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, C., Liu, Q. & Song, J. Boundary-enhanced sparse transformer for generalizable and accurate medical image segmentation. Sci Rep 16, 2191 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33686-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33686-0