Abstract

To efficiently utilize the olive germplasm resources in the Bailong River Valley region of Longnan, China, the oil content of fresh fruits from 98 olive germplasm samples and three maturity stages (Ⅰ, Ⅱ, Ⅲ) was determined and analyzed. Additionally, 13 oil-related traits were studied using variation, correlation, cluster, and principal component analyses (PCA), aiming to screen excellent germplasm resources through comprehensive evaluation. The results showed that the oil content of fresh fruits exhibits a wide range and increases with maturity: I: 28.00% ~ 60.20%; II: 32.50% ~ 64.60%; III: 34.10% ~ 64.80%. Oleic acid (C18:1) was the predominant fatty acid, and ‘Grisha’ exhibited the highest content across all three maturity stages. In terms of genetic variation, the coefficients of variation for 13 traits across 98 olive germplasm resources exhibited significant variability. PCA reduced the 13 traits to five principal components, which collectively accounted for a cumulative contribution rate of 77.87%. The comprehensive evaluation has identified the top five olive germplasm resources across three maturity stages, including ‘K2’, ‘Agiou orous’, ‘FS17’, among others. Cluster analysis classified germplasms into three distinct categories (Group I, II, III). Group I is recommended as core germplasm resources suitable for bulk commodity oil production. Group II represents ideal material for cultivating highly stable specialty oils and fats. Meanwhile, Group III offers valuable resources for developing hypoglycemic and lipid-lowering functional oils. This study establishes a foundation for olive breeding, cultivation promotion, and processing in Longnan, China.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Olive (Olea europaea L.), an oil crop belonging to the genus Olea in the Oleaceae family, is a prominent subtropical fruit tree and a key woody oil tree species. It is primarily distributed in Mediterranean coastal countries such as Spain, Italy, and Greece1. In China, Longnan City in Gansu Province, located at 33°N latitude, is designated as a “National Olive Demonstration Base.” It lies at the same latitude as the Mediterranean region, known as the “world’s golden zone for olive production,” making Longnan one of the prime cultivation areas for olives in China. The olive cultivation in Longnan is primarily concentrated in Wudu District2,3. Olive oil and edible olives are recognized as healthy food options. Notably, olive oil—particularly extra virgin olive oil (EVOO)—is rich in monounsaturated fatty acids, especially oleic acid (C18:1), which constitutes over 70% of its composition. Furthermore, as the fruit ripens, the quality of most varieties of olives improves significantly. It also contains polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), including linoleic acid (C18:2) and α-linolenic acid (C18:3)4,5. Additionally, olive oil is rich in sterols, with β-sitosterol being the primary component, typically constituting 75–90% of the sterol fraction. β-sitosterol is considered a primary contributor to the antioxidant activity and other beneficial effects associated with olive oil sterols6,7. Squalene is an open-chain triterpenoid compound, which has multiple physiological functions including enhancing superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity within the body, enhancing immune function, improving sexual function, as well as possessing anti-aging, anti-fatigue, and anti-tumor properties8,9. Additionally, the phenolic compounds and vitamin E present in olive oil contribute significantly to its functional components by providing various health benefits. Among these constituents, α-tocopherol predominates among vitamin E forms (accounting for over 80%) and plays a crucial role in scavenging reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated by endogenous systems10. Consequently, olive oil is recognized as a valuable vegetable oil that enjoys widespread use across the globe.

As far as we know, the oil content is one of the important indicators for evaluating the quality of olive fruits11,12. In Longnan City, Gansu Province, China, the critical period for oil accumulation begins in August every year and lasts until the harvest season in November. However, the oil content and composition are influenced by the variety13, the time and method of harvest14, environmental factors15,16, and extraction technology17. Caponio et al18. found that during the entire maturation process, the oil content in fresh olive fruits initially increases and then stabilizes. In a study on the qualitative characteristics of olive fruits cultivated in southwestern China, it was observed that during fruit maturation, both oil content and fruit weight increase rapidly, following an “S”-shaped accumulation pattern19. The fatty acid composition and the content of lipid concomitant substances are also critical indicators for assessing oil quality. Esti et al.20 found that during the maturation of the ‘Leccino’ and ‘Frantoio’ cultivars, C18:1 content increased while palmitic acid (C16:0) decreased, whereas linoleic acid (C18:2) content increased with maturity in the ‘Coratina’ cultivar but decreased in ‘Leccino’ and ‘Frantoio’. Previous studies have concluded that environmental conditions have a relatively low influence on fatty acid composition, with cultivar and maturity level being the most relevant factors affecting fatty acid profile and oil quality21,22.

Currently, research on olive fruit maturation both domestically and internationally primarily focuses on growth and development, phenotypic traits, fatty acid composition and content, oil content, and functional components3,22. To enhance oil quality and economic benefits for growers, and to determine the optimal harvest time, it is essential first to clarify the differences among olive oils extracted from fruits of different cultivars and at different maturity stages. Subsequently, the optimal harvest period can be selected based on varying trends in fatty acid categories and secondary lipid metabolites23,24. Accordingly, this study selected fresh fruit samples from 98 olive germplasms in the National Forest Tree Germplasm Resource Bank for Olives in Longnan City. Thirteen oil quality indicators were measured at three maturity stages: oil content, C16:0, palmitoleic acid (C16:1), stearic acid (C18:0), C18:1, C18:2, C18:3, arachidic acid (C20:0), cis-11-eicosenoic acid (C20:1), squalene, β-sitosterol, total polyphenols, and α-tocopherol. Through correlation analysis, PCA, and systematic cluster analysis, a comprehensive evaluation was conducted to elucidate quality differences among different olive cultivars and maturity stages. The aim is to provide a theoretical basis for guiding appropriate olive harvesting, ensuring optimal fruit quality, and promoting diversified utilization.

Materials and methods

Overview of the test site

The experimental site is located in the Bailong River Valley area of Wudu District, Longnan City, Gansu Province. It is situated at 33° 24’N, 104° 55’E, with an altitude of 1,079 m. The annual average temperature is 14.2℃ and the annual average sunshine duration is 1,560.4 h. The extreme maximum temperature is 35.6℃ and the minimum temperature is − 8.1℃. The annual average precipitation is 551.2 mm and the relative humidity is 61%. It belongs to the dry and hot river valley area of the northern subtropical zone, similar to the Mediterranean climate, and is suitable for the cultivation of olive oil.

Plant materials

The experiment was conducted in 2021 at the National Forest Tree Germplasm Resource Bank of Olive Trees in Longnan City, Gansu Province. A total of 98 germplasm samples were collected (Table 1), all of which were grafted in the spring of 2019. The rootstock was the Chenggu 18a variety. The tree growth was good, and the site conditions and planting management levels such as water and fertilizer were basically the same.

Sampling method

The maturity of the fruit is classified based on the color of the fruit skin. In this study, oil olive maturity is categorized into three grades: yellowish-green fruit skin represents first maturity (Ⅰ), predominantly purple fruit skin indicates second maturity (Ⅱ), and purple-black skin signifies third maturity (Ⅲ). During sampling, for each germplasm of the same variety, samples were randomly collected from different positions on various trees, ensuring that they were free from pests and diseases and exhibited consistent appearance (similar color, size, and shape). For each of the three maturity levels sampled, approximately 250 g of fruit was collected per variety. The physiological indicators such as fruit weight and both longitudinal and transverse diameters of 20 olive fruits were measured immediately. The remaining fruits were gathered and promptly refrigerated before being transported back to the Economic Forest Product Quality Inspection and Testing Center under the National Forestry and Grassland Administration for subsequent determination and analysis of their oil quality indicators.

Oil content

The collected fruits were dried in an oven at 105 °C until a constant mass was achieved before being crushed. The determination of oil content in these fruits was conducted following the “National Food Safety Standard—Determination of Fat in Foods.” A sample weighing 5 g was placed into a filter paper bag; petroleum ether (30–60 °C) served as the solvent for Soxhlet extraction to calculate oil content. This process was repeated three times to obtain an average value. The formula used for calculating oil content is: Oil content (%) = (mass of extracted oil / mass of fruit) × 100%. Detailed methodology follows that described by Emmanouilidou et al.25.

Fatty acid components

The method for determining fatty acid components was conducted in accordance with GB 5009.168–2016 “National Food Safety Standard—Determination of Fatty Acids in Foods” (China)26.

Squalene, β-sitosterol, total phenol, and α-tocopherol contents

The squalene content was quantified following LS/T6120-2017 “Grain and Oil Inspection—Determination of Squalene in Vegetable Oils—Gas Chromatography Method” (China). The β-sitosterol content determination adhered to NY/T3111-2017 “Determination of Sterol Content in Vegetable Oils—Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry” (China). Additionally, the assessment methods for total polyphenols and vitamin E contents were based on Li et al.27.

Data analysis

The data for each trait were processed using Excel 2021 to perform descriptive statistical analysis. The maximum value (MAX), minimum value (MIN), average value, standard deviation (SD), median, and coefficient of variation (CV) for each numerical trait were calculated. Factor analysis was conducted utilizing SPSS 23.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) statistical software. Correlation analysis, cluster analysis, and graphical plotting were performed using Origin 2024 (OriginLab, Northampton, Massachusetts, USA). Additionally, the membership function method and principal component analysis (PCA) were employed to conduct a comprehensive evaluation of oil content, fatty acid components, and active substances.

Results and discussion

Oil content of fresh fruits of 98 olive germplasm resources at three stages of maturity

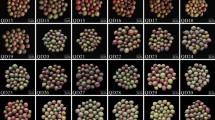

Taking the maturity appearance of four olive varieties (Adramittini, Ascolano Tenera, Coratina and Arbequina) as an example, as shown in Fig. 1, the appearance colors yellowish green—mostly purple—purple-black correspond to three maturity levels I—II—III respectively.

The oil content is a critical parameter for assessing the quality of olive fruits. It not only influences the oil yield but also correlates closely with the fatty acid composition and nutritional value of olives28. Generally, oil accumulation continues until full fruit maturity; however, the oil extraction rate may either increase or decrease depending on the maturity stage of the olive29. The statistical analysis of oil content across three maturity stages in 98 olive germplasm samples revealed a clear and significant trend characterized by initial accumulation followed by stabilization (Table 2). Although individual germplasm accessions exhibited considerable variation in oil content—ranging from 28.00 to 60.20% at the initial stage, the population-level mean values displayed a consistent pattern: oil content increased substantially from I to III, with only a marginal or statistically non-significant change observed between the second and third stages. For example, the accession exhibiting the highest final oil content (S74, 64.80%) showed a net increase of approximately 16 percentage points over the maturation period, closely aligning with the overall population trend. This pattern indicates that, in most cultivars, the primary phase of active oil biosynthesis is largely completed by the end of the second maturity stage, beyond which further accumulation reaches a plateau. These findings provide strong statistical support for defining the optimal harvest window to maximize oil yield as encompassing the latter two maturity stages.

The observed trend of initial increase followed by stabilization can be attributed to the physiological shift in fruit metabolism during ripening. Initially, oil content rises steadily on a dry weight basis, driven by active triacylglycerol synthesis and deposition. As ripening progresses, this trend stabilizes. Two key factors underlie this shift: the dilution effect of increasing fruit water content on dry-matter concentration metrics, and a likely redirection of metabolic resources toward the production of secondary metabolites or other physiological functions. These findings align with reports of a positive correlation between maturity and oil content30, as well as with patterns of peak accumulation at intermediate maturity followed by stabilization or slight decline 31,32.

Fatty acid composition

In this study, eight types of fatty acids were identified in all 98 tested virgin olive oils. C18:1, recognized as the most significant monounsaturated fatty acid in olive oil. From Table 3, it can be observed that the mean oleic acid content reached 72.01%, 70.58%, and 68.26% at three different maturity stages respectively, with coefficients of variation recorded at 6.44%, 6.97%, and 8.59%. These results indicate that variations in C18:1 across different varieties and maturity periods are not pronounced. At maturity levels I, II, and III, S12 exhibited the highest oleic acid contents at values of 82.90%, 79.19%, and 78.91% respectively; conversely, S56 (61.40%), S77 (58.90%), and S66 (51.90%) displayed the lowest contents. The content of C16:0 and C18:2 is the second highest (Table 3 and supplementary Table S1).

Meanwhile, the research indicated that the oleic acid content in most olive varieties decreased as maturity increased. Koseoğlu et al.33 observed that with the transition of olive skin color from green to black, there was a corresponding decrease in oleic acid levels within the olive oil. The linoleic acid content ranged from 5.01% to 11.81%, falling within the limits of 2.5%—21.0% established by International Olive Oil Council (IOOC). During the maturation process, both Memecik and Gemlik olive oils exhibited an increase in linoleic acid concentrations. de et al.34 noted that as fruit ripening progressed, percentages of palmitic acid and linoleic acid tended to decline, while oleic acid content peaked at the highest ripening index. Other studies have similarly reported a reduction in oleic acid alongside an increase in linoleic acid during maturation35,36. The could be explained by oleic acid desaturase, in which oleic acid is converted to linoleic acid37.

Nutrient composition analysis

Beyond its richness in essential unsaturated fatty acids, olive oil is also a significant source of bioactive compounds such as squalene and β-sitosterol. As presented in Table 3, analysis of 98 olive oil samples revealed the following squalene content ranges across three maturity levels: 544.30–10,698.00 mg/kg, 695.00–11,519.60 mg/kg, and 846.60–14,574.30 mg/kg, respectively. The corresponding mean β-sitosterol contents were 1460.93 mg/kg, 1439.71 mg/kg, and 1444.64 mg/kg. Germplasms exhibiting the highest squalene levels at each maturity stage were S8, S85, and S54, respectively (Table 3, Supplementary Table S2). In the study by Gunduz et al38., the β-sitosterol content of the ‘Saurani’ and ‘Karamani’ olive varieties decreased as ripening. Yu et al.39 reported a decrease in squalene content and a sharp increase in total sterol content with advancing maturity within the same olive variety. These trends are largely consistent with the findings of the present study. This results indicated that the β-sitosterol content of the olive oils was significantly affected by variety and ripening. Furthermore, our results indicate a gradual decline in total phenolic compounds as the fruit ripens, aligning with numerous reports on various olive cultivars40,41. The content of α-tocopherol also displayed considerable variability across samples, with coefficients of variation of 46.47%, 47.10%, and 47.91% at the three maturity levels. The mean α-tocopherol concentrations were 21.59, 21.52, and 21.36 × 10⁻2mg/g, respectively. Yu et al.39 found that the content of α -tocopherol decreased significantly with the increase of maturity. However, in this study, the content of α -tocopherolof the same variety decreased slightly with the increase of maturity, but the trend was not obvious. This difference may stem from factors such as variety, altitude, and oil extraction process.

Correlation analysis of oil quality indicators

Figure 2a, b, and c correspond to maturity stages Ⅰ, Ⅱ, and Ⅲ, respectively, displaying Pearson correlations among oil content, fatty acid components, and bioactive compounds (such as squalene, total polyphenols, and α-tocopherol). Among these, C18:1 and C18:2 consistently exhibited a very strong and statistically significant negative correlation across all three stages (r = -0.89), indicating an inherent relationship throughout maturation. At stage Ⅰ, C20:0 showed a significant positive correlation with C16:0 (r = 0.74), while C16:1 correlated negatively with C18:1 (r = -0.67) and positively with C20:0 (r = 0.67). Additionally, C20:1 was positively correlated with C18:1 (r = 0.51). In stage Ⅱ, the positive correlation between C20:0 and C16:0 slightly strengthened (r = 0.75), the negative correlation between C16:1 and C18:1 became somewhat more pronounced (r = -0.69), and C18:3 showed a positive correlation with C18:2 (r = 0.53). By stage Ⅲ, the positive correlation between C20:0 and C16:0 weakened (r = 0.62), whereas C16:1 displayed a very strong positive correlation with C20:0 (r = 0.81**), and the positive correlation between C20:1 and C18:1 significantly strengthened (r = 0.61).

This correlation pattern reflects metabolic regulation during oil maturation. The persistent strong negative correlation between oleic acid and linoleic acid stems from their competitive dependence on △12 fatty acid desaturase (FAD2) for synthesis. The stable activity of this enzyme throughout maturation leads to a metabolic trade-off between the precursor (C18:1) and the product (C18:2). The significant positive correlation between C20:0 and C16:0 in stages Ⅰ and Ⅱ reflects the elongation of C16:0 for long-chain saturated fatty acid synthesis during early maturation. The weakening of this correlation in stage Ⅲ suggests a downregulation of carbon chain elongation enzyme activity and a subtle shift in fatty acid synthesis flux later in maturation. Furthermore, correlations between bioactive compounds such as squalene and total polyphenols with fatty acids were generally weak and showed no consistent pattern. This indicates that their accumulation pathways are relatively independent of fatty acid metabolism, likely influenced by distinct regulatory mechanisms.

Comprehensive score analysis

PCA can be used to explain and analyze the differences among multi-dimensional samples, and further obtain the key comprehensive analysis factors of samples with a large number of intricate relationships42. In this study, PCA was performed on 13 quality indicators of olive fruits across three maturity levels (I, II, and III) (Table 4). Five principal components were extracted based on eigenvalues exceeding 1. The cumulative variance contribution rates for the components were 76.11%, 75.40%, and 73.75% respectively, indicating that these five components effectively encapsulated the primary information from the original indicators. I: PC1 (25.61%) primarily represents C16:1, C20:1, and C16:0; PC2 emphasizes β-sitosterol and total polyphenols; PC3 (13.38%) reflects unsaturated fatty acids (C18:3, C18:2, C18:1); PC4 includes C20:0 and C18:0; while PC5 (9.00%) highlights oil content and squalene. II: PC1 (27.40%) comprehensively encompasses C16:1, C16:0, and C20:1 with the highest loading attributed to C16:1; PC2 (16.11%) represents both C18:0 and C20:0; PC3 contains β-sitosterol along with C18:3; PC4 (10.62%) involves a combination of C18:2, C18:1, and total polyphenols; whereas PC5 is predominantly composed of oil content and squalene. III: PC1 (28.90%) integrates data from C16:0, C16:1, and C20:1; PC2 (14.65%) comprises β-sitosterol, C18:3, C18:2, and C18; PC3 signifies both C18:0 and C20:0. PC4 underscores squalene and oil content; PC5 (8 0.27%) is mainly characterized by total polyphenols.

Among the three maturity levels, PC1 was consistently dominated by C16:0, C16:1, and C20:1, accounting for 25.61% to 28.90% of the variance. This finding indicates that the composition of medium-chain fatty acids serves as the fundamental framework of olive oil. This observation aligns with the perspective of the IOOC, which emphasizes palmitoleic acid (C16:1) as a key indicator for geographical indication43. The relative abundance of this fatty acid increased with fruit maturity (from 0.34 to 0.39), reflecting a greater concentration on fatty acid accumulation during later stages of fruit metabolism44. The evolution observed in PC2 transitions from representing a “health factor” (β-sitosterol and total polyphenols) at I stage to a “mixed functional factor” (β-sitosterol alongside C18 series USFA) at III stage. This shift reveals a temporal coupling between active ingredients and fatty acid metabolism throughout maturation. In early stages, there was a high polyphenol load (0.97), consistent with the enrichment pattern typically seen in olive polyphenols during the green fruit stage45. Conversely, its association with USFA in later stages suggests that sterols may play a regulatory role in determining fatty acid composition46. Furthermore, both oil content and squalene were continuously co-loaded within either PC4 or PC5 across all three maturity stages; this confirms their co-evolution regarding oil accumulation and antioxidant capacity. Squalene functions as a triterpene precursor positively correlated with lipid synthesis47. Notably, polyphenols independently formed PC5 at maturity level III, underscoring the specificity inherent to late-stage metabolic pathways associated with polyphenols48.

Taking the proportion of the contribution rates corresponding to the five principal components to the total contribution rate as the weight, the comprehensive evaluation function of 98 olive germplasms was obtained (Table 5, Supplementary S3). Ⅰ: F = 0.34 PC1 + 0.24 PC2 + 0.18 PC3 + 0.13 PC4 + 0.12 PC5; II: F = 0.36 PC1 + 0.21 PC2 + 0.17 PC3 + 0.14 PC4 + 0.12 PC5; Ⅲ : F = 0.39 PC1 + 0.20 PC2 + 0.17 PC3 + 0.13 PC4 + 0.11 PC5; The principal component scores, comprehensive scores and rankings of each superior germplasm were calculated. Comprehensive evaluation identified the top five varieties for oil quality. I: K2 > FS17 > Nikiskii > Gai > Lyuan Manzanilla de Sevilla. II: Agiou orous > FS17 > Nikiskii > Megaritiki > Gai; III: Agiou orous > FS17 > Nikiskii > Lyuan Manzanilla de Sevilla > Megaritiki. At maturity I (early harvest), K2, FS17, and others demonstrated superior performance, which can be attributed to their elevated polyphenol content (PC2 weight 0.24) and favorable fatty acid profiles (PC1). This observation aligns with the “outstanding functionality” characteristics associated with early harvest oils. Furthermore, FS17 consistently ranks among the top two across all three maturity levels, its stability may result from the co-expression of fatty acid desaturase (FAD2) and sterol synthase (SQS)49. K2, which ranks first in early harvests due to its high polyphenol content, experiences a decline in ranking during late harvests. This trend is consistent with the degradation pattern of polyphenols as maturation progresses50,51. At II and III (mid-late harvest), Agiou orous and FS17 maintained a leading position owing to the dominance of C16:1 (PC1 weight 0.36–0.39) and their capacity to retain late squalene compounds (PC4). Generally, oxidative stability exhibited an increasing trend during the early stages of maturity but subsequently declined in the later stages51,52. Nevertheless, Agiou orous and FS17 continued to demonstrate superior oxidative stability compared to other late-maturing varieties.

In conclusion, FS17 is recommended as the primary cultivated variety for ensuring stable production; Agiou orous is suitable for producing mid-to-late harvest commercial oil; while K2 and Lyuan Manzanilla de Sevilla are appropriate for developing functional oils.

Cluster analysis

To further investigate the characteristics of 98 types of olive oil, 13 quality indicators were selected for cluster analysis. It can be observed from Fig. 3a–c and Table 6 that cluster analysis categorizes the samples into three distinct groups.

Group I exhibited high C18:1 and low C18:2 characteristics at I and II, subsequently evolving to a profile characterized by high oil content coupled with enhanced antioxidant capacity (high squalene or total polyphenols) at III. This progression indicates that the synthesis of secondary metabolites, such as squalene, is augmented during the later stages of maturation, thereby improving the overall quality of the oil53. Consequently, this group can serve as a core germplasm for bulk commodity oil production. Its elevated antioxidant properties in later stages may also contribute to an extended shelf life. In contrast, Group II undergoes significant transformations throughout its maturation process. At maturity stage I, it displays high oil content alongside robust antioxidant capacity; however, in maturities II and III, there is a notable reduction in saturated fatty acids accompanied by an increase in α-tocopherol content. As a key liposoluble antioxidant, the enrichment of α-tocopherol appears to be independent of variations in fatty acid composition, suggesting the presence of specific genetic regulatory modules49.

It is noteworthy that this germplasm maintains elevated antioxidant indicators across all three mature stages, rendering it an ideal candidate for cultivating highly stable specialty oils. During the maturation process of Group III, active components continue to accumulate: at maturity stage I, it exhibits low levels of saturated fatty acids while being rich in β-sitosterol and α-tocopherol; at maturity stage II, there are lower oleic acid levels along with increased concentrations of squalene and β-sitosterol; finally, at maturity stage III, palmitic acid levels rise significantly while oleic acid remains low. Notably, β-sitosterol has been shown to inhibit cholesterol absorption6,7, whereas squalene enhances cellular membrane antioxidant defenses8,9. Additionally, C16:1 was recognized as a rare fatty acid type capable of activating peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ), plays a role in improving glucose metabolism54 and regulating insulin sensitivity. Thus far-reaching implications suggest that this type of germplasm represents a valuable resource for developing hypoglycemic and lipid-lowering functional oils.

Conclusions

This study analyzed the key indicators of extra virgin olive oil (EVOO) derived from 98 olive varieties at three maturity levels (I, II, and III). The results indicate a wide range of oil content in the fruits, with the average oil content increasing from 47.19% (I) to 49.90% (III), suggesting that olives in the Longnan area possess high oil content. The average oleic acid content—a monounsaturated fatty acid and a critical quality indicator, decreased with advancing maturity (I: 72.01%; II: 70.58%; III: 68.26%), yet remained relatively high overall, thereby confirming the excellent quality of local oils. Regarding active compounds, squalene exhibited considerable variability and significantly increased with maturity. The contents of β-sitosterol (averaging approximately 1460–1444 mg/kg) and α-tocopherol (averaging around 21.5 × 10⁻2mg/g) were relatively stable across different maturity stages. Correlation analysis revealed a significant positive correlation between oil content and squalene; however, total polyphenols did not show significant correlations with other properties. Based on a comprehensive evaluation using PCA, it was determined that ‘FS17’ is suitable as the primary variety for stable production; ‘Agiou orous’ is appropriate for mid-to-late harvest commercial oil production; while ‘K2’ and ‘Lyuan Manzanilla de Sevilla’ are recommended for developing functional oils. Future research should integrate transcriptomics to analyze the molecular mechanisms underlying principal component variations and validate the universality of this comprehensive evaluation model on a larger field scale.

Data availability

The data used for the analysis in this study are presented in the article and supplementary File 1.

References

Talhaoui, N., Taamalli, A., Gómez-Caravaca, A. M., Fernández-Gutiérrez, A. & Segura-Carretero, A. Phenolic compounds in olive leaves: Analytical determination, biotic and abiotic influence, and health benefits. Food Res. Int. 77, 92–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2015.09.011 (2015).

Su, C. J., Sun, J. F., Zhu, W. Z. & Peng, L. History, distribution, and potential of the olive industry in China: A review. Sustainability 10, 1426. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10051426 (2018).

Yang, L. et al. Evolution of phenotypic traits and main functional components in the fruit of ‘Chenggu-32’ olives (Olea europaea L.) Cultivated in Longnan (China). J. Oleo. Sci. 69(9), 973–984. https://doi.org/10.5650/jos.ess19329 (2020).

Cunnane, S. C. Problems with essential fatty acids: time for a new paradigm?. Prog Lipid Res. 42(6), 544–568. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0163-7827(03)00038-9 (2003).

Katsiki, N., Pérez-Martínez, P. & Lopez-Miranda, J. Olive oil intake and cardiovascular disease prevention:“Seek and you shall find”. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 23(6), 64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11886-021-01496-1 (2021).

Lukic, M., Lukic, I. & Moslavac, T. Sterols and triterpene diols in virgin olive oil: a comprehensive review on their properties and significance, with a special emphasis on the influence of variety and ripening degree. Horticulturae https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae7110493 (2021).

Rallo, L. et al. Quality of olives: A focus on agricultural preharvest factors. Sci. Hortic. 233, 491–509. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2017.12.034 (2018).

Rondanini, D. P., Castro, D. N., Searles, P. S. & Rousseaux, M. C. Contrasting patterns of fatty acid composition and oil accumulation during fruit growth in several olive varieties and locations in a non-Mediterranean region. Eur. J. Agron. 52, 237–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eja.2013.09.002 (2014).

Beltrán, G., Bucheli, M. E., Aguilera, M. P., Belaj, A. & Jimenez, A. Squalene in virgin olive oil: Screening of variability in olive cultivars. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 118, 1250–1253. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejlt.201500295 (2016).

Bouymajane, A. et al. Characterization of phenolic compounds, vitamin E and fatty acids from Monovarietal Virgin Olive Oils of “Picholine marocaine” cultivar. Molecules 25, 5428. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25225428 (2020).

Ferro, M. D., Cabrita, M. J., Herrera, J. M. & Duarte, M. F. A new laboratory scale olive oil extraction method with comparative characterization of phenolic and fatty acid composition. Foods 12(2), 380. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12020380 (2023).

Wang, J. W. et al. Youth tree behavior of olive (Olea europaea L.) cultivars in Wudu, China: Cold and drought resistance, growth, fruit production, and oil quality. Sci. Hortic. 236, 106–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2018.03.033 (2018).

El Riachy, M., Hamade, A., Ayoub, R., Dandachi, F. & Chalak, L. Oil content, fatty acid and phenolic profiles of some olive varieties growing in Lebanon. Front. Nutr. 6, 458819. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2019.00094 (2019).

Polari, J. J. M. & MaryWang, S. C. Virgin olive oils from super-high-density orchards in California: Impact of cultivar, harvest time, and crop season on quality and chemical composition. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 123(3), 2000180. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejlt.202000180 (2021).

Zago, L., Squeo, G., Bertoncini, E. I., Difonzo, G. & Caponio, F. Chemical and sensory characterization of Brazilian virgin olive oils. Food Res. Int. 126, 108588. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2019.108588 (2019).

Dag, A. et al. Influence of time of harvest and maturity index on olive oil yield and quality. Sci. Hortic. 127(3), 366. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.9665 (2011).

De Ceglie, C. et al. Influence of horizontal centrifugation processes on the content of phenolic secoiridoids and their oxidized derivatives in commercial olive oils: an insight by liquid chromatography–high-resolution mass spectrometry and chemometrics. J. Agric. Food Chem. 68(10), 3171–3183. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.0c00455 (2020).

Caponio, F., Gomes, T. & Pasqualone, A. Phenolic compounds in virgin olive oils: Influence of the degree of olive ripeness on organoleptic characteristics and shelf-life. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 212(3), 329–333. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002170000268 (2001).

Cheng, Z. et al. The major qualitative characteristics of olive (Olea europaea L.) cultivated in southwest China. Front. Plant Sci. 8, 559. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2017.00559 (2017).

Esti, M., Gambacorta, G., Carrone, A. & Trivisonno, M. C. Caratteristiche qualitative e compositive di oli vergini di oliva prodotti in Molise. Riv Ital Sostanze Gr. 73(3), 101–106 (1996).

Miho, H., Moral, J., López-González, M. A., Díez, C. M. & Priego-Capote, F. The phenolic profile of virgin olive oil is influenced by malaxation conditions and determines the oxidative stability. Food Chem. 314, 126183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.126183 (2020).

Rosa, R. D. L., Talhaoui, N., Rouis, H., Velasco, L. & Leon, L. Fruit characteristics and fatty acid composition in advanced olive breeding selections along the ripening period. Food Res. Int. 54(2), 1890–1896. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2013.08.039 (2013).

Beltrán, G., Del Rio, C., Sánchez, S. & Martínez, L. Influence of harvest date and crop yield on the fatty acid composition of virgin olive oils from cv. Picual. J Agric Food Chem. 52(11), 3434–3440. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf049894n (2004).

Ferrara, L. A. et al. Olive oil and reduced need for antihypertensive medications. Arch Intern Med. 160, 837–842. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.160.6.837 (2000).

Emmanouilidou, M. G., Koukourikou-Petridou, M., Gerasopoulos, D. & Kyriacou, M. C. Oxidative stability, fatty-acid and phenolic composition of Cypriot monovarietal virgin olive oils with progressive fruit maturity. J. Food Compos. Anal. 104, 104191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfca.2021.104191 (2021).

Tao, F. & Ngadi, M. Recent advances in rapid and nondestructive determination of fat content and fatty acids composition of muscle foods. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 58(9), 1565–1593. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2016.1261332 (2018).

Long, L. et al. Fatty acids and nutritional components of the seed oil from Wangmo red ball Camellia oleifera grown in the low-heat valley of Guizhou. China. Sci Rep. 12(1), 16554. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-20576-y (2022).

Zipori, I. et al. Effect of macronutrient fertilization on olive oil composition and quality under irrigated, intensive cultivation management. J. Sci. Food Agric. 103(1), 48–56. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.12110 (2023).

Rio, C. D., Beltran, G., Sanchez, S. & Martinez, L. Seasonal changes in olive fruit characteristics and oil accumulation during ripening process. Sci. Food Agric. 84(13), 1783–1790. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.1887 (2010).

Tang, F. et al. Effect of variety and maturity index on the physicochemical parameters related to virgin olive oil from wudu (China). Foods 12(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12010007 (2022).

Nergiz, C. & Ergönül, P. G. Organic acid content and composition of the olive fruits during ripening and its relationship with oil and sugar. Sci. Hortic. 122, 216–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2009.05.011 (2009).

Yang, L. et al. Changes in quality and antioxidant properties of virgin olive oil of ‘Cornicabra’ according to fruit maturation in Longnan. China. J. Oleo Sci. 70(12), 1731–1740. https://doi.org/10.5650/jos.ess20289 (2021).

Köseoğlu, O., Sevim, D. & Kadiroğlu, P. Quality characteristics and antioxidant properties of Turkish monovarietal olive oils regarding stages of olive ripening. Food Chem. 212, 628–634. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.06.027 (2016).

de Mendoza, M. F. et al. Chemical composition of virgin olive oils according to the ripening in olives. Food Chem. 141(3), 2575–2581. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.05.074 (2013).

Ceci, L. N., Mattar, S. B. & Carelli, A. A. Chemical quality and oxidative stability of extra virgin olive oils from San Juan province (Argentina). Food Res. Int. 100, 764–770. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2017.07.074 (2017).

Alowaiesh, B., Singh, Z., Fang, Z. X. & Kailis, S. G. Harvest time impacts the fatty acid compositions, phenolic compounds and sensory attributes of Frantoio and Manzanilla olive oil. Sci. Hortic. 234, 74–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2018.02.017 (2018).

Ouni, Y., Flamini, G. & Zarrouk, M. The chemical properties and volatile compounds of virgin olive oil from Oueslati variety: Influence of maturity stages in olives. J. Am. Oil. Chem. Soc. 93, 1265–1273. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11746-016-2863-0 (2016).

Gunduz, G. & Konuskan, D. B. Fatty acid and sterol compositions of Turkish Monovarietal olive oils with regard to olive ripening. J. Oleo Sci. 72(1), 79–85. https://doi.org/10.5650/jos.ess22239 (2023).

Yu, L. et al. Chemical and volatile characteristics of olive oils extracted from four varieties grown in southwest of China. Food Res. Int. 140, 109987. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2020.109987 (2021).

de Torres, A. et al. Assessment of phenolic compounds in virgin olive oil by response surface methodology with particular focus on flavonoids and lignans. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 90, 22–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2017.12.003 (2018).

Hachicha Hbaieb, R., Kotti, F., Gargouri, M., Msallem, M. & Vichi, S. Ripening and storage conditions of Chétoui and Arbequina olives: Part I. Effect on olive oils volatiles profile. Food Chem. 203, 548–558. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.01.089 (2016).

Cecchi, L. et al. Clustering monovarietal extra virgin olive oil according to sensory profile, volatile compounds, and k-mean algorithm. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejlt.202200038 (2022).

Boskou, D., Blekas, G. & Tsimidou, M. Olive Oil Composition. Olive Oil (Second Edition). 41–72 (2006).

Stefanoudaki, E., Williams, M., Chartzoulakis, K. & Harwood, J. Olive oil qualitative parameters after orchard irrigation with saline water. J. Agric. Food Chem. 57(4), 1421–1425. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf8030327 (2009).

Ryan, D., Antolovich, M., Prenzler, P., Robards, K. & Lavee, S. Biotransformations of phenolic compounds in Olea europaea L. Sci. Hortic. 92(2), 147–176 (2002).

Vlahakis, C. & Hazebroek, J. Phytosterol accumulation in canola, sunflower, and soybean oils: Effects of genetics, planting location, and temperature. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 77(1), 49–53 (2000).

Guinda, Á. et al. Determination of major bioactive compounds from olive leaf. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 64(1), 431–438. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2015.05.001 (2015).

Ghanbari, R., Anwar, F., Alkharfy, K. M., Gilani, A. H. & Saari, N. Valuable nutrients and functional bioactives in different parts of olive (Olea europaea L.)-a review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 13(3), 3291–3340. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms13033291 (2012).

Hernández, M. L., Padilla, M. N., Mancha, M. & Martínez-Rivas, J. M. Expression analysis identifies FAD2-2 as the olive oleate desaturase gene mainly responsible for the linoleic acid content in virgin olive oil. J. Agric. Food Chem. 57(14), 6199–6206. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf900678z (2009).

Baccouri, O. et al. Chemical composition and oxidative stability of Tunisian monovarietal virgin olive oils with regard to fruit ripening. Food Chem. 109, 743–754. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.01.034 (2008).

Ghreishi Rad, S. A., Jalili, M., Ansari, F., Rashidi Nodeh, H. & Rashidi, L. Maturity impact on physicochemical composition and polyphenol properties of extra virgin olive oils obtained from Manzanilla, Arbequina, and Koroneiki varieties in Iran. Food Sci. Nutr. 11(9), 5396–5408. https://doi.org/10.1002/fsn3.3497 (2023).

Ben Youssef, N. et al. Effect of olive ripeness on chemical properties and phenolic composition of Chétoui virgin olive oil. J. Sci. Food Agric. 90, 199–204. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.3784 (2010).

Kalua, C. M. et al. Olive oil volatile compounds, flavour development and quality: A critical review. Food Chem. 100(1), 273–286 (2007).

Dicks, L. M. T. How important are fatty acids in human health and can they be used in treating diseases?. Gut Microbes. 16(1), 2420765. https://doi.org/10.1080/19490976.2024.2420765 (2024).

Funding

This research was funded by the Gansu Provincial Science and Technology Plan Project for Innovative Talents in Science and Technology (25JR6KA019), and the Gansu Province Leading Talent Program (GSBJLJ-2023-09).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.Y.J., W.J.W. conceived and designed the experiments. M.L. collected documents, drafted manuscripts, and organized data. G.M.J., J.L.Q., Y.F.Y. and C.C.Z. participated in most of the experiments and data collection. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, M., Wu, W., Jin, G. et al. Comprehensive evaluation of oil quality of 98 olive germplasms at 3 maturity levels from the Bailong River Valley area in Longnan, China. Sci Rep 16, 3734 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33724-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33724-x