Abstract

Leprosy is a debilitating disease that requires early detection for effective control, yet diagnosis still relies on clinical signs. Previous RNA-Seq analysis of coding genes from leprosy patients’ household contacts (HHC) who developed leprosy (progressors) and those who did not, revealed a 4-gene RNA signature, RISK4LEP, that predicted leprosy 4–61 months before clinical onset (AUC: 0.86). To improve this signature, the present study included non-coding genes and applied novel Differential Gene Expression (DGE) analyses and machine learning approaches to the RNA-Seq dataset. This strategy identified significant DGE between progressors and HHC for 40 genes. Next, the 10 most significantly different expressed genes, as well as genes from the optimal 3-gene signatures, were validated by RT-qPCR in an independent cohort. This analysis confirmed the diagnostic potential to discriminate progressors from HHC for 12 genes. Moreover, RPS21 and SNHG5 genes were each significantly higher expressed in progressors compared to diagnosed leprosy patients, suggesting their temporary role during early (preclinical) leprosy. Furthermore, the optimal 3-gene signature consisted of two non-coding genes and one coding gene (SNHG5, SNHG8, C6orf48; sensitivity: 88%; specificity: 88%; AUC: 0.96). This study thus identified an improved prospective host transcriptional risk signature in blood based on non-coding genes predicting the development of leprosy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Leprosy is a chronic infectious disease caused by Mycobacterium leprae or M. lepromatosis, likely transmitted via droplets from contagious patients1. About 170,000 new cases occur annually, mainly in low socio-economic regions1. The disease affects the skin and peripheral nerves and, if untreated, can cause irreversible disabilities, stigma, and social exclusion2. Leprosy presents various clinical forms, ranging from tuberculoid (TT) with low bacterial index (BI) and strong cellular immunity3 to lepromatous (LL) with high bacterial load and humoral response3,4. Intermediate forms include borderline tuberculoid (BT), borderline borderline (BB), and borderline lepromatous (BL)5. The WHO classifies cases as paucibacillary (≤ 5 lesions, no detectable bacilli) or multibacillary (> 5 lesions and/or positive skin smear)1,6,7.

Leprosy diagnosis is primarily clinical, based on skin lesions with sensory loss, peripheral nerve thickening, and detection of M. leprae8. The wide disease spectrum complicates diagnosis7, and often requires expertise of experienced clinicians to obtain invasive samples like skin smears or biopsies9. Early detection of leprosy is characterized as one of the main challenges to stop transmission and prevent irreversible handicaps due to tissue damage caused by M. leprae10,11,12. Therefore, the identification of host biomarkers that can identify M. leprae infection or the onset of disease in low-invasive samples would be a game-changer for leprosy control. In this respect, monitoring household contacts (HHC) remains crucial, as they are intensely and frequently exposed to the bacterium and thus at greater risk of developing leprosy7,13.

Since the identification of new host biomarkers can provide new insights into pathogenesis and ways to differentiate between the various spectral forms in the disease spectrum, including early disease and M. leprae infection without clinical signs14, the identification of host proteomic and transcriptomic biomarkers for leprosy has been studied intensely in the past years10,11,12,15,16,17,18,19.

Non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) are genomic elements that are not translated into proteins, playing a regulatory role in gene expression. Recently, the use of ncRNA as host biomarkers for infectious diseases has gained attention. This included microRNAs (miRNAs), which are small non-coding RNAs, and long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) that were found to be associated with the regulation of the immune response against M. leprae and disease progression20,21,22,23. The expression of some miRNAs was shown to discriminate leprosy patients from healthy subjects in a Brazilian cohort using skin specimens23,24 as well as blood samples23, thereby highlighting the possible role of non-coding genes for the diagnosis of leprosy23,24.

Previously, we identified a four-gene signature, designated RISK4LEP (MT-ND2, REX1BD, TPGS1, UBC), that differentiated HHC who later developed PB leprosy (designated progressors) from those who did not in a leprosy endemic population in Bangladesh10,25. As point-of-care (PoC) tests assessing RNA expression of host genes in fingerstick blood did not exist yet at the time of the previous study, we then focused on the identification of genes encoding for serum proteins that could be detectable in capillary blood using a lateral flow format, while excluding non-coding genes from the validation process.

Recently, Sutherland et al.. described the use of the Cepheid GeneXpert MTB-HR prototype, a finger-stick blood test measuring the RNA expression levels of three different genes (GBP5, DUSP3, and KLF2)26,27, to discriminate TB from other respiratory diseases (ORD), thereby highlighting the potential of host transcriptomic biomarkers in PoC diagnostic tests26,27.

Considering the regulatory roles of ncRNAs, a host transcriptomic biomarker signature that includes non-coding genes could provide a more complete insight into the overall transcriptome in leprosy pathogenesis. Therefore, the present study reanalyzed the RNA-Seq dataset, including ncRNA10,25, and combined three established methodologies (edgeR, DESeq2, and Limma-Voom), as well as two machine learning approaches (Random Forest-RF and Support Vector Machine-SVM), to establish an improved gene host biomarker profile able to predict leprosy. The results of this study can contribute to the improvement of early diagnosis and prediction of leprosy.

Materials and methods

Ethics

Ethical permission for leprosy patients’ samples was received from the National Research Ethics Committee (Bangladesh Medical Research Council) in Bangladesh (Ref no. BMRC/NREC/2010–2013/1534 and BMRC/NREC/2016–2019/214)28 and local ethical boards in the Netherlands (MEC-2012-589), and followed the Helsinki Declaration (version Fortaleza, Brazil, October 2013). Participants were informed about the study objectives in their local language and provided written informed consent before being included in the study. All participants were informed about their right to refuse to take part or withdraw from the study without consequences.

Description of cohorts

Between April 2013 and April 2018, HHC (n= 5,352) of newly diagnosed leprosy patients were enrolled in the study, and a first blood sample was collected (t = 1) from participants in four districts of the northwest region of Bangladesh. A more detailed description can be found in Tió-Coma et al.10.. Briefly, HHC were classified as individuals living in the same house, within the same compound, sharing a kitchen, or as direct (first) neighbors of individuals diagnosed with leprosy. Exclusion criteria included individuals with prior leprosy, those who refused consent, pregnant women, (treated) tuberculosis patients, children under five years old, individuals with liver disease or jaundice, and temporary residents29. HHC were monitored annually for at least 36 months to check for leprosy symptoms, with follow-up until 2022. HHC diagnosed with leprosy 4–61 months after t = 1 were classified as progressors. A second blood sample was collected from progressors at diagnosis, before starting multidrug therapy (t = 2). Progressors who presented with five or fewer skin lesions and BI = 0 were classified as PB, while those with more than five skin lesions were classified as MB6. An initial set was drawn from the cohort, consisting of 39 HHC and 39 progressors who were diagnosed with leprosy 4–61 months after recruitment10.

To validate the results from the initial set, a validation set was later drawn from the same follow-up, which included 12 HHC and 12 progressors (validation cohort) who were diagnosed with leprosy 4–61 months after recruitment. ECs are characterized as individuals from the general population of the same area who have had no known contact with leprosy patients30. The demographic information of the different groups is described in Supplementary Table S1.

RNA isolation, library preparation, and sequencing

Venous blood was collected in PAXgene tubes (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ), frozen until shipment on dry ice to Leiden University Medical Centre (LUMC, The Netherlands) for analysis. The RNA isolation from PAXgene tubes was automated using a QIAcube machine (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and PAXgene blood RNA kits (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA concentrations were measured by Qubit RNA BR Assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). The libraries for sequencing were prepared using NEBNext Ultra II Directional RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA), which includes poly(A) enrichment, and the globin reduction was performed using GLOBINclear kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Clustering and sequencing were performed in a NovaSeq6000 System (Illumina, San Diego, CA). The library preparation and sequencing followed the methodological approach outlined in previously10.

RNA-Sequencing analysis

RNA-Seq files were processed using the open-source BIOWDL RNA-Seq pipeline v2.0 (https://github.com/biowdl/RNA-seq/tree/v2.0.0) developed at Leiden University Medical Centre. The pipeline of the RNA-Seq used in this study was based on the framework established by previously10.

Reversed transcribed quantitative PCR (RT qPCR)

RNA was reverse-transcribed into cDNA by annealing phase at 25 °C for 5 min, extending phase at 42 °C for 60 min, and deactivation phase at 70 °C for 15 min using the GoScript™ Reverse Transcription System kit (Promega A5001) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Subsequently, a quantitative PCR was performed by mixing 10 µl of GoTaq® Probe qPCR Master Mix (Promega, A6102), 3 µl of nuclease-free water, 1 µl of the primer solution for the target gene (Supplementary Table S2), 1 µl of the primer solution for the reference gene GAPDH (Hs99999905_m1), and 5 µl of the cDNA sample. To monitor assay performance, ROX dye (Thermo Fisher) was added to the qPCR mix. Nuclease-free water was used as a negative control. cDNA was amplified using the following protocol: 2 min at 95 °C followed by 40 cycles of 15 s at 95 °C and 1 min at 60 °C in the QuantStudio 6 Flex Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). Relative target gene expression was determined by calculating ∆Ct using GAPDH as a reference gene. Since mRNA levels of immune genes were expressed as ΔCt values, larger values represent lower mRNA levels in the sample. To obtain the correct orientation, the ΔCt values were multiplied by −1.

Differential gene expression analysis using multi-method integration

Differential gene expression (DGE) was performed from RNA-Seq data10 analysis to identify genes differentially expressed between the leprosy progressor patients at t = 1 and the HHC group that presented statistical significance. DGE analysis was performed using three different established libraries, edgeR, DESeq2, and Limma-Voom, executed according to their guidelines31,32,33. In the edgeR and Limma-Voom, the raw counts were normalized for library sizes with the Trimmed Mean of the M-values (TMM) method. In the DESeq2 library, the median of ratios normalization method was used. The p-values were adjusted for multiple testing with the Benjamini-Hochberg statistical method to control the false discovery rate34. Genes with false discovery rates below 0,05 (adjusted p-values < 0,05) and above log2(1,5) or below -log2(1,5) threshold were classified as differentially expressed. These methods were applied to all genes, coding and non-coding genes, separately. The analyses were performed using R (version 4.4.1) and the RStudio program for Windows 11.

Machine learning approaches

The intersection of genes from the DGE analysis shared between the three libraries was divided into three categories: whole RNA-Seq, coding genes, and non-coding genes. Through two different feature selection techniques, the chi-square test and the recursive feature elimination (RFE), different group sizes between three and 20 genes were generated for each of the 3 categories. These groups were then applied in two different machine learning approaches, the Random Forest (RF) and the Support Vector Machine (SVM). For the RF method, the Leave One Out cross-validation (LOOCV) method was applied, consisting of iterations between one sample as a validation set and the remaining samples to train the model. This procedure was repeated five times. For the SVM, LOOCV was applied without the five-times iteration, since SVM is a deterministic approach. The analyses were performed in PyCharm Edu (version 2020.2.1) and scikit-learn (version 1.4.1) using Python (version 3.10) for Windows 11. To compare the different subgroups generated through RF and SVM, the area under the curve (AUC) score was determined using a test set. These methods were applied to the whole RNA-Seq, coding genes, and non-coding gene groups separately.

Based on the average of higher AUC score values from both RF and SVM approaches, the best group size of genes was chosen in the whole RNA-Seq, coding genes, and non-coding genes groups, totaling six groups. After that, the intersection genes between the RF and SVM approaches were selected in the three different gene groups. The genes in the intersection of RF and SVM were split into coding and non-coding genes and ranked according to previously determined order of significance by the EdgeR, DESeq2, and LimmaVoom libraries, resulting in three different rankings. The ten most significant genes of each library were compared, and the common genes were selected. The RISK4LEP gene signature was included in the intersection of common genes of these two different machine learning approaches. Based on the intersection of shared genes, the chi-square and the RFE methods were applied to generate subgroups of three genes, after which the subgroups were applied in RF and SVM.

Statistical analysis in the validation cohort

DGE analysis of RT-qPCR data of the validation cohort of progressors and HHC was performed by comparing the median expression between the two groups and was evaluated with the Mann-Whitney test. When the comparison was made with more than two groups, the difference in median expressions between groups was assessed with the Kruskal-Wallis test, followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. The DGE was considered significant when its corresponding p-value was below the 0,05 threshold. The analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (version 9.3.1) for Windows.

Results

Differential gene expression in blood between leprosy progressors and HHC before leprosy diagnosis

In a previous study, we analyzed RNA-Seq data of a cohort of HHC in Bangladesh to identify leprosy risk-predicting host transcriptomic biomarkers encoding for serum proteins that could apply to rapid PoC diagnostic tests. Therefore, non-coding genes were excluded from that analysis10. Since the potential of host transcriptomic biomarkers in PoC diagnostic tests26,35 was recently demonstrated for TB, the current study aimed to optimize the previously identified host transcriptomic biomarker signature that predicted risk of developing leprosy (RISK4LEP)10, by including also non-coding genes in the RNA-Seq data for evaluation of their discriminatory potential for progressors and HHC.

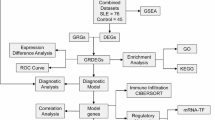

Since performing different analyses and combining various analytical frameworks can help mitigate bias and ensure reliable findings, identification of DGE between progressors (n = 39) and HHC (n = 39), using the same RNA-seq data10, was here performed through three different statistical analyses: the DESeq2, EdgeR, and LimmaVoom methods as summarized in the study design pipeline in Fig. 1 and further detailed in Supplementary Fig. S1.

Schematic overview of analyses used to discover host transcriptomic biomarkers predicting the risk for leprosy. Including both coding and non-coding genes from the RNA-Seq data, a funnel approach of statistical analysis identified 19 candidate biomarkers, of which 14 were testable in RT-qPCR and 12 validated as host transcriptomic biomarkers associated with risk of leprosy. FC: Fold Change; RFE: Recursive feature Elimination; RF: Random Forest; SVM: Support Vector Machine. * Three of the 4 genes in the RISK4LEP gene signature were added for comparative purposes; one of the genes (TPGS1) was among 37 genes identified by the current analysis.

From 58,741 genes included in total in the RNASeq dataset (coding and non-coding genes), the DESeq2 method identified 344 genes as significantly differentially expressed between progressors and HHC. Among these, 142 were upregulated and 202 were downregulated (Supplementary Figure S2). Using the EdgeR method, 367 DEGs were found, with 183 upregulated and 184 downregulated. The LimmaVoom method identified 187 DEGs, of which 101 were upregulated and 86 were downregulated. For each method, the 20 most significant genes are highlighted in the volcano plots in Supplementary Figure S2.

Comparison of the three analytical methods (DESeq2, EdgeR, and LimmaVoom) identified 108 genes that were identified by all 3 methods, including 62 coding and 46 non-coding (Figs. 2a, b, and c, respectively). DEG identified in the subgroups (coding or only non-coding genes) are described in Supplementary Tables S4 and S5, respectively.

Venn diagram representing DEGs of whole blood RNA expression of leprosy progressors (n = 39) and household contacts (HHC) (n = 39) in (a) the whole RNA-Seq dataset (b) coding, or (c) non-coding genes. DEGs were identified using three statistical methods (DESeq2, EdgeR, and LimmaVoom). Numbers within the diagrams indicate either the overlap of DEGs between the 3 methods or DEGs uniquely identified by each method.

Application of different machine learning approaches to identify genes capable of predicting leprosy development

Next, two different machine learning models (RF and SVM) were applied to the DEGs that were identified by all 3 methods mentioned above in either the whole RNA-Seq dataset (n = 108), coding (63), and non-coding (45) genes. In addition, using different feature importance parameters (RFE and chi-squared methods), groups of 3 to 20 genes were generated to identify the optimal gene combination (based on the AUC score) able to predict leprosy. Out of the 108 genes, 37 DEGs were identified by RF as well as SVM and included for further analysis (Supplementary Table S6). From these 37 genes, one gene was previously identified in the RISK4LEP signature (TPGS1). For the sake of comparison, we also included the other three RISK4LEP genes (MT-ND2, REX1BD, and UBC) for further validation10. Among these 40 DEG, 18 were coding and 22 were non-coding genes (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. S1; Supplementary Fig. S3).

Application of machine learning approaches to identify the optimal 3-biomarker signature to predict leprosy

To identify the best combination of genes that jointly identify progressors amongst HHC, feature selection was performed on the 40 selected genes to identify the optimal 3-gene combination in analogy to the 3-gene biomarker signature for active TB. In the RF approach, RFE identified SNHG8, C6orf48, and SNHG5 as the optimal gene combination (AUC:0.96; sensitivity (Sn): 88%; specificity (Sp): 88%; Supplementary Table S7). Using the chi-square method, the best 3 gene-combination consisted of UBC, RPL18AP3, and RPS21 (AUC: 0.85; Sn: 76%; Sp: 78%; Supplementary Table S7). In the SVM approach, RFE identified TRIM74, RP11-385D13.3, and TMEM238 as the best combination (AUC:0.94; Sn:85%; Sp:95%). When chi-square was applied in SVM, the same optimal gene set as in RF (UBC, RPL18AP3, and RPS21 genes) was obtained, but with an improved performance (AUC: 0.91; Sn:77%; Sp:85%).

Validation of host transcriptomic biomarkers for leprosy prediction

From the 40 genes, the ten most significant coding and non-coding genes were ranked, and the genes shared between the DGE approaches were selected (Supplementary Table S8). This selection, along with the groups containing the optimal 3-gene combinations, yielded 19 genes, of which 14 were commercially available for RT-qPCR purposes, characterized by C6orf48, UBC, MT-CO1, C12orf57, MZT2B, MT-ND2, TMEM238, DPM3, RPL13AP5, RPSAP58, SNHG8, SNHG5, RPS21, and TRIM74. These genes were tested in a different independent cohort of 12 progressors and 12 HHC from the same area in northwest Bangladesh for subsequent validation.

Of the 14 tested genes, 12 were significantly differentially expressed between progressors and HHC: RPSAP58, RPS21, C12orf57, SNHG5, DPM3, SNHG8, C6orf48, UBC, TMEM238, RPL18AP5, and TRIM74 were upregulated in the progressors group compared to the HHC, while MT-ND2 was downregulated (Fig. 3). No significant differences were found for MT-CO1 and MZT2B.

Differential gene expression (DGE) in whole blood samples between progressors and household contacts (HHC). mRNA levels were measured by RT-qPCR in whole blood RNA samples of progressors (n = 12) and HHC (n = 12). The Mann–Whitney U test was performed to determine the statistical significance between groups (adjusted p-values: * p < 0,05, ** p < 0,01, *** p < 0,001, **** p < 0,0001). Relative target gene expression was determined by calculating ∆Ct using GAPDH as a reference gene. Since mRNA levels were expressed as ΔCt values, larger values represent lower mRNA levels. ΔCt values were multiplied by −1.

The discriminatory potential of these genes in distinguishing progressors from HHC was assessed as well, and yielded the highest AUC values for RPSAP58, C12orf57, and RPS21 (0.96, 0.92, and 0.90, respectively) (Supplementary Fig. S4). Remarkably, RPSAP58 achieved a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 83%, underscoring its outstanding potential as a host biomarker for discriminate progressors from HHC. C12orf57 had a sensitivity of 83% and a specificity of 92%, whereas RPS21 achieved a sensitivity of 75% and a specificity of 92% (Supplementary Fig. S4).

To validate the optimal 3-gene signature (SNHG8, C6orf48, and SNHG5) found in the RNA-Seq analysis, NUM-scores (based on the sum of the number of individual positive biomarkers detected) were calculated using optimal cut-offs (Youden’s index)14,36, to evaluate discrimination between progressors and HHC in the validation cohort. This 3-gene signature achieved a Sn of 100% and Sp of 66,67% (AUC: 0.92; Supplementary Fig. S5). If we consider the second-highest Youden index value, this signature achieved a SN of 83,33% and Sp of 75%. These findings highlight the pivotal contribution of non-coding genes, in conjunction with coding genes, to improve early diagnosis and accurate prediction of leprosy.

Assessment of host transcriptomic biomarkers in leprosy patients

Since the RNA-Seq dataset was based on whole blood RNA expression levels in contacts of leprosy 4–61 months before diagnosis (progressors) or contacts never developed disease (HHC), we now also assessed the12 DEGs in MB, PB, and compared thee to the group of progressors and HHC as well as an endemic control (EC) group (Fig. 4). Progressors presented a higher expression of RPS21 and SNHG5 compared to PB patients and a higher expression of RPS21 and C12orf57 compared to EC and HHC, while SNHG5 and DPM3 presented a higher expression only related to HHC (Fig. 4). DPM3 also presented a significant downregulation in MB patients compared to EC and progressors (Fig. 4).

MB and PB patients showed significantly higher expression of SNHG8 and C6orf48 compared to HHC. SNHG8 also presented a higher expression in MB patients compared to progressors (Fig. 4). The C6orf48 presented significantly increased expression in the PB patients compared to EC. Furthermore, UBC expression was higher in MB patients compared to EC (Fig. 4).

TMEM238 and RPSAP58 presented significantly different DEGs between the groups PB, MB, progressors, EC, and HHC. Both genes presented a higher expression in the EC group compared to progressors and HHC. Furthermore, they also showed an upregulation in PB patients compared to HHC (Fig. 4). TMEM238 presented a higher expression in PB patients compared to MB patients and progressors. RPSAP58 also showed an upregulation in MB patients compared to HHC (Fig. 4). All the significantly DEGs are described in Supplementary Table S9. These findings describe the potential role of RPS21 and SNHG5 in the progression of leprosy, suggesting a temporary role during the early (preclinical) stages of the disease. The main results of this study are described in the Supplementary Fig. S5.

Differential gene expression (DGE) in whole blood samples between multibacillary (MB) patients, paucibacillary (PB), endemic controls (EC), progressors, and household contacts (HHC). The mRNA levels were measured by RT-qPCR in human samples of MB (n = 17), PB (n = 16), EC (n = 16), progressors (n = 12), and HHC (n = 12). The Kruskal-Wallis test, followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test, was performed to determine the statistical significance between groups (adjusted p-values: * p < 0,05, ** p < 0,01, *** p < 0,001, **** p < 0,0001). The horizontal lines indicate the median with the interquartile range. GAPDH was used as a reference gene, as highlighted in Fig. 3.

Discussion

Leprosy is a chronic infectious disease that can cause nerve damage, disability, and stigma if untreated2. M. leprae’s slow growth delays symptoms and potentially allows silent transmission37, while diagnosis still relies on clinical expertise and invasive tests9. A low complexity test based on host biomarkers that can be identified in minimally invasive samples would facilitate leprosy care. Recent advances in host transcriptomic biomarker signatures offer promising tools for diagnosis, early detection, and surveillance of leprosy10,11,12,18,19,38. The successful application of host transcriptomic biomarkers in PoC tests has been described for tuberculosis: the Cepheid GeneXpert MTB-HR test evaluates three genes (GBP5, DUSP3, and KLF2) that distinguish active TB from other respiratory diseases (ORDs) using fingerstick blood26,27,39, demonstrating the potential of host transcriptomic-based diagnostics as PoC tests.

Recent studies have demonstrated that non-coding genes, such as miRNAs and lncRNAs, are involved in the regulation of leprosy pathogenesis21,22,23. Cáceres-Durán et al.. highlighted a miRNA signature composed of hsa-miR-16-5p, hsa-miR-106b-5p, hsa-miR-1291, hsa-miR-144-5p, and hsa-miR-20a-5p, can discriminate between individuals without leprosy and leprosy patients40. The function of these miRNAs in leprosy patients may lead to the dysregulation of several biological pathways, such as apoptosis, autophagy, cell cycle regulation, and mitophagy40. These studies highlight the potential of non-coding genes as host biomarkers to improve leprosy diagnostics and provide insights into the immunopathology of this disease.

In this study, 12 individual genes were differentially expressed between progressors from HHC in a validation cohort, highlighting these host transcriptomic biomarkers as promising candidates for early leprosy. Also, the differential expression of these genes across progressors, PB, MB, EC, and HHC groups was evaluated.

An optimal 3-gene signature (SNHG5, SNHG8, and C6orf48) was identified, which achieved a sensitivity of 88% and specificity of 88% (AUC = 0.96), with higher expression in progressors compared to HHCs who did not develop disease. The C6orf48 gene is reported to be possibly involved in translation processes, in association with ribosomal proteins, in colon cancer41. Moreover, polymorphisms in this gene, located at chromosome 6 in the MHC III region, are positively correlated with the susceptibility to the development of breast cancer in a Chinese cohort42. For SNHG5, a long non-coding RNA (lncRNA), several functions have been described, such as cell survival, differentiation, and migration43. Similarly, this gene also plays a pivotal role in the development of different types of cancer43. For example, the inhibition of SNHG5 in the human leukemia cell line promotes the reduction of cell proliferation and induction of apoptosis44. SNHG5 is also involved in the modulation of immune responses, wherein the upregulation of this gene is related to a reduction of inflammation, once this gene binds to nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) p65 subunit, thereby promoting the signaling inhibition and reduction of the inflammatory response cascade45. This could indicate that SNHG5 participates in the regulation of immune response, in an attempt to dampen pro-inflammatory signaling as present in those HHCs who develop to PB leprosy. SNHG8, like SNHG5, belongs to the lncRNA family and shares functions with SNHG5, indicating its regulatory role in cellular functions, such as cell survival, differentiation, and migration46,47,48,49.

The 3-gene signature identified in the present study (SNHG5, SNHG8, and C6orf48) outperformed the RISK4LEP signature (MT-ND2, REX1BD, TPGS1, and UBC; Sn:87.5%; Sp: 72.3%; AUC: 0,86). In this study, the optimal 3-gene signature achieved a Sn of 100% and Sp of 67% (AUC: 0.92). This improvement highlights the value of incorporating non-coding genes, which can capture critical disease-related regulatory signals. When opting for higher specificity (75%), sensitivity was decreased to 83,33%. However, when targeting all individuals who will develop leprosy for prophylactic treatment, a higher sensitivity is preferred to minimize missed cases, although specificity remains important to avoid overtreatment.

The current data also showed that RPS21 and SNHG5 expression were significantly higher in progressors compared to PB patients and HHC who did not develop disease. The elevated expression of these genes in HHC who progress to disease later indicates a temporary activation of these genes during early (preclinical) disease, which decreases again after development of clinical PB disease. The gene RPS21 encodes a component of the 40 S ribosomal subunit50. This gene has been described as upregulated in metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma cells, reported as a promising prognostic biomarker for patients with this disease51,52. It has been reported that the increase of RPS21 is negatively correlated with GPX4 enzyme ubiquitination, a key regulator of ferroptosis. The stability of GPX4 leads to a reduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels and the inhibition of ferroptosis52. During M. leprae infection, a reduction of oxidative stress could favor bacterial survival and progression of disease. Furthermore, variants of other genes encoding ribosomal proteins, such as the mitochondrial ribosomal protein S5 (MRPS5) gene, were shown to contribute to risk for leprosy in a Chinese population53. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to report RPS21 and SNHG5 as promising host transcriptomic biomarkers for detecting leprosy in its early stages.

In our findings, the SNHG8 gene was found to be higher in MB patients compared to progressors. In line with our findings on the biomarker potential of lncRNA, Fava et al.., who identified a lncRNA with two isoforms, RP11-135D11.2, and an uncharacterized LOC105378318 gene with two variants, rs1875147 and rs10826321, which were potential risk factors for the development of leprosy type-1 reactions (T1R)22. Although downregulated in MB patients, the DPM3 gene also showed discriminatory potential. This gene encodes subunit 3 of the dolichol-phosphate mannose (DPM) synthase complex, which is comprised of two other subunits, DPM1 and DPM254,55. DPM synthase plays a role in a range of glycosylation processes, such as N-glycosylation and O-mannosylation56. Once downregulated in MB patients, this could indicate that glycosylation may be altered, like the synthesis of truncated N-glycans and hypo-O-mannosylated proteins57. All these processes would affect multiple immune response pathways, such as lymphocyte activation and immune signaling58, leading to a poor cellular immunity against M. leprae.

Although in the current study we analyzed multiple clinical groups, all samples were collected in Bangladesh. As socioeconomic, environmental, genetic, and demographic factors can influence RNA expression, future studies with cohorts from other countries are essential to validate our findings worldwide. However, evaluation of the DEGs from this study in an alternative cohort might be challenging, as the current analysis was based on > 9 years of sampling of HHCs without leprosy and active case finding by field staff due to the low number of HHCs who develop leprosy after infection, as well as the long incubation time of leprosy.

In summary, analysis of RNA-Seq data of HHC of leprosy patients in Bangladesh using a combination of novel DGE analyses and machine learning approaches resulted in validation of 12 genes differentially expressed between progressors and HHC (RPSAP58, RPS21, C12orf57, SNHG5, DPM3, SNHG8, C6orf48, MT-ND2, UBC, TMEM238, RPL13AP5, and TRIM74). Three of these genes, SNHG5, SNHG8, and C6orf48, jointly formed the most optimal 3-gene signature, which achieved a sensitivity of 88% and specificity of 88% (AUC = 0.96). Moreover, RPS21 and SNHG5 genes were significantly higher expressed in progressors compared to diagnosed PB patients. This study identifies promising new host biomarkers that may contribute to improved targeting of prophylactic measures to prevent leprosy, enhance prognosis and diagnosis, and provide a better understanding of the immunopathology of the disease.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

WHO. The World Health Organization has published its latest Global Leprosy. (Hansen Disease) Update, 2024: beyond zero Cases — What elimination of leprosy really means. in World Health Organization. 20, 365-384 (2024).

Rathod, S. P., Jagati, A. & Chowdhary, P. Disabilities in leprosy: an open, retrospective analyses of institutional records. Bras. Dermatol. 95, 52–56 (2020).

Saini, C., Ramesh, V. & Nath, I. CD4 + Th17 cells discriminate clinical types and constitute a third subset of Non Th1, Non Th2 T cells in human leprosy. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 7, e2338 (2013).

de Sousa, J. R., Sotto, M. N. & Simões Quaresma, J. A. Leprosy as a complex infection: breakdown of the Th1 and Th2 immune paradigm in the Immunopathogenesis of the disease. Front. Immunol. 8, 1635 (2017).

Ridley, D. S. & Jopling, W. H. Classification of leprosy according to immunity. A five-group system. Int. J. Lepr. Other Mycobact. Dis. 34, 255–273 (1966).

WHO. Guidelines for the diagnosis, treatment and prevention of leprosy. World Health Organization, 106 (2018).

van Hooij, A. & Geluk, A. In search of biomarkers for leprosy by unraveling the host immune response to Mycobacterium leprae. Immunol. Rev. 301, 175–192 (2021).

(WHO), W.H.O. Global leprosy (Hansen disease) update, 2023: Elimination of leprosy disease is possible – Time to act! World Health Organization. (2024).

Braet, S. M. et al. Minimally invasive sampling to identify leprosy patients with a high bacterial burden in the union of the Comoros. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 15, e0009924 (2021).

Tió-Coma, M. et al. Blood RNA signature RISK4LEP predicts leprosy years before clinical onset. EBioMedicine 68, 103379 (2021).

Leal-Calvo, T. et al. A new paradigm for leprosy diagnosis based on host gene expression. PLoS Pathog. 17, e1009972 (2021).

Ferreira, H. et al. Gene expression patterns associated with multidrug therapy in multibacillary leprosy. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 12, 917282 (2022).

Moet, F. J., Pahan, D., Schuring, R. P., Oskam, L. & Richardus, J. H. Physical distance, genetic relationship, age, and leprosy classification are independent risk factors for leprosy in contacts of patients with leprosy. J. Infect. Dis. 193, 346–353 (2006).

van Hooij, A. et al. Prototype multi-biomarker test for point-of-care leprosy diagnostics. iscience. 24, 102006-102016 (2021).

Zhou, Q. et al. Identification of potential biomarkers of leprosy: A study based on GEO datasets. Plos One. 19, e0302753 (2024).

van Hooij, A. et al. Application of new host biomarker profiles in quantitative point-of-care tests facilitates leprosy diagnosis in the field. EBioMedicine 47, 301–308 (2019).

Santos, M. et al. Distinct roles of Th17 and Th1 cells in inflammatory responses associated with the presentation of paucibacillary leprosy and leprosy reactions. Scand. J. Immunol. 86, 40–49 (2017).

Yuan, Y. H. et al. Transcriptomic analysis of Mycobacterium leprae-Stimulated response in peripheral blood mononuclear cells reveal potential biomarkers for early diagnosis of leprosy. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 11, 714396 (2021).

Das, M. et al. Mycobacterium leprae and host immune transcriptomic signatures for reactional States in leprosy. Front. Microbiol. 14, 1113318 (2023).

Santosh, B., Varshney, A. & Yadava, P. K. Non-coding rnas: biological functions and applications. Cell. Biochem. Funct. 33, 14–22 (2015).

Santana-da-Silva, M. N. et al. NcRNAs: an unexplored cellular defense mechanism in leprosy. Front. Genet. 14, 1295586 (2023).

Fava, V. M. et al. A genome wide association study identifies a LncRna as risk factor for pathological inflammatory responses in leprosy. PLoS Genet. 13, e1006637 (2017).

Salgado, C. G. et al. MiRNome expression analysis reveals new players on leprosy immune physiopathology. Front. Immunol. 9, 463 (2018).

Jorge, K. et al. Characterization of MicroRNA expression profiles and identification of potential biomarkers in leprosy. J. Clin. Microbiol. 55, 1516–1525 (2017).

Palmeirim, M. S. et al. Advancing Mycobacterium leprae transmission research: insights from the R2STOP fund. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 19, e0013370 (2025).

Sutherland, J. S. et al. Diagnostic accuracy of the cepheid 3-gene host response fingerstick blood test in a Prospective, Multi-site study: interim results. Clin. Infect. Dis. 74, 2136–2141 (2022).

Sutherland, J. S. et al. Performance of 2 Finger-Stick blood tests to triage adults with symptoms of pulmonary tuberculosis: A prospective multisite diagnostic accuracy study. Clinical Infect. Diseases, 81, 857-866, (2025).

van Hooij, A. et al. Quantitative lateral flow strip assays as User-Friendly tools to detect biomarker profiles for leprosy. Sci. Rep. 6, 34260 (2016).

Richardus, R. et al. The combined effect of chemoprophylaxis with single dose rifampicin and immunoprophylaxis with BCG to prevent leprosy in contacts of newly diagnosed leprosy cases: a cluster randomized controlled trial (MALTALEP study). BMC Infect. Dis. 13, 456. 10.1186 (2013).

Richardus, R. A. et al. The combined effect of chemoprophylaxis with single dose rifampicin and immunoprophylaxis with BCG to prevent leprosy in contacts of newly diagnosed leprosy cases: a cluster randomized controlled trial (MALTALEP study). BMC Infect. Dis. 13, 456 (2013).

Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated Estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15, 550 (2014).

Ritchie, M. E. et al. Limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, e47 (2015).

Robinson, M. D., McCarthy, D. J. & Smyth, G. K. EdgeR: a bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 26, 139–140 (2010).

Benjamini, Y. & Hochberg, Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. Roy. Stat. Soc.: Ser. B (Methodol.). 57, 289–300 (1995).

Fluss, R., Faraggi, D. & Reiser, B. Estimation of the Youden index and its associated cutoff point. Biom J. 47, 458–472 (2005).

Illarramendi, X. A promising whole-blood biomarker to aid leprosy control. EBioMedicine. 68, 103413 (2021).

Tió-Coma, M. et al. Whole blood RNA signatures in leprosy patients identify reversal reactions before clinical onset: a prospective, multicenter study. Sci. Rep. 9, 17931 (2019).

Wu, X. et al. Assessment of the cepheid 3-gene host response fingerstick blood test (MTB-HR) on rapid diagnosis of tuberculosis. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 12, 2261561 (2023).

Cáceres-Durán, M. et al. MicroRNA biomarkers in leprosy: insights from the Northern Brazilian Amazon population and their implications in disease immune-physiopathology. Front. Genet. 15, 1320161 (2024).

Maertens, A. et al. Functionally enigmatic genes in cancer: using TCGA data to map the limitations of annotations. Sci. Rep. 10, 4106 (2020).

Pan, Q. et al. Association of MHC class-III gene polymorphisms with ER-positive breast cancer in Chinese Han population. Genet. Mol. Res. 11, 4299–4306 (2012).

Han, W., Shi, J., Cao, J., Dong, B. & Guan, W. Latest advances of long non-coding RNA SNHG5 in human cancers. OncoTargets Therapy, 13, 6393–6403 (2020).

Gao, B., Li, S., Li, G. & Long Noncoding, R. N. A. lncRNA) small nucleolar RNA host gene 5 (SNHG5) regulates Proliferation, Differentiation, and apoptosis of K562 cells in chronic Myeliod leukemia. Med. Sci. Monit. 25, 6812–6819 (2019).

Han, Y. et al. Long non-coding RNA SNHG5 mediates periodontal inflammation through the NF-κB signalling pathway. J. Clin. Periodontol. 49, 1038–1051 (2022).

Qian, J. et al. Long non-coding RNA SNHG8 enhances triple-negative breast cancer cell proliferation and migration by regulating the miR-335-5p/PYGO2 axis. Biol. Direct. 16, 1–10 (2021).

Yu, B. et al. LncRNA SNHG8 promotes proliferation and inhibits apoptosis of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma via sponging miR-335-5p. Front. Oncol. 11, 650287 (2021).

Tian, X., Liu, Y., Wang, Z. & Wu, S. LncRNA SNHG8 promotes aggressive behaviors of nasopharyngeal carcinoma via regulating miR-656-3p/SATB1 axis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 131, 110564 (2020).

Khan, M. Z. I. & Law, H. K. W. Suppression of small nucleolar RNA host gene 8 (SNHG8) inhibits the progression of colorectal cancer cells. Non-coding RNA Res. 8, 224–232 (2023).

Bhat, K. S. & Morrison, S. G. Primary structure of human ribosomal protein S21. Nucleic Acids Res. 21, 2939 (1993).

Pan, J. et al. Identification of ribosomal protein S21 as a potential prognostic and immunotherapy biomarker for hepatocellular carcinoma. Asian J. Surg, 48, 137-149 (2024).

Wu, S., Wang, G., Gu, L., Zhang, Y. & Wang, Z. RPS21 enhances hepatocellular carcinoma development through GPX4 stabilization. Transl Oncol. 51, 102189 (2025).

Xing, Y. et al. Polymorphisms in mitochondrial ribosomal protein S5 (MRPS5) are associated with leprosy risk in Chinese. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 14, e0008883 (2020).

Maeda, Y. & Kinoshita, T. Dolichol-phosphate mannose synthase: structure, function and regulation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1780, 861–868 (2008).

Maeda, Y., Tanaka, S., Hino, J., Kangawa, K. & Kinoshita, T. Human dolichol-phosphate-mannose synthase consists of three subunits, DPM1, DPM2 and DPM3. Embo j. 19, 2475–2482 (2000).

Svahn, J. et al. Dilated cardiomyopathy and limb-girdle muscular dystrophy-dystroglycanopathy due to novel pathogenic variants in the DPM3 gene. Neuromuscul. Disord. 29, 497–502 (2019).

Chapman, A., Trowbridge, I. S., Hyman, R. & Kornfeld, S. Structure of the lipid-linked oligosaccharides that accumulate in class E Thy-1-negative mutant lymphomas. Cell 17, 509–515 (1979).

Radovani, B. & Gudelj, I. N-glycosylation and inflammation; the not-so-sweet relation. Front. Immunol. 13, 893365 (2022).

Ryan, S. O. & Cobb, B. A. Major histocompatibility complex: N-Glycosylation form and function. Glycoscience: Biology Med. Springer 643–648 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This work was made possible thanks to the Q.M. Gastmann-Wichers foundation (AG), the R2STOP Research grant from effect: hope, Canada, and the Mission to End Leprosy, Ireland; the Order of Malta-Grants-for-Leprosy-Research, and the Leprosy Research Initiative (LRI), together with the Turing Foundation (ILEP# 702.02.73 and # 703.15.07). MA was supported by LUMC Global, Fundação Oswaldo Cruz (FIOCRUZ), and Fundação para o Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico em Saúde (FIOTEC). Some figures for this article were created with BioRender.com.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: AGData curation: MA, SV, AR, EE, EG, AH, FVFormal analysis: MA, AR, EE, FV, AH, AGFunding acquisition: CM, AGSampling: MK, AS, KA, SSSample database: AH, JRInvestigation: MA, SV, LM, AR, EE, EG, AH, AGMethodology: MA, EG, SV, LM, AGProject administration: AGResources: AGSoftware: MA, SV, AR, EE, FVSupervision: AH, AGVisualization: MA, EG, AR, EE, AH, AGWriting – original draft: MA, CM, AGReview and editing: All authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Almeida, M.R., Gherardi, E., van Veen, S. et al. Advancing leprosy risk prediction through identification of a whole blood host transcriptomic biomarker signature including non-coding genes. Sci Rep 16, 3781 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33878-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33878-8