Abstract

Drought is a significant challenge to winter wheat production. Its impact can be mitigated by preventing plant moisture stress through precision agriculture. Remote sensing and machine learning have proven effective for managing moisture stress in winter wheat. This study highlights the potential of new indices that combine visible (VIS) and near-infrared (NIR) bands along with canopy temperature (Tc), to monitor plant moisture content (PMC) and leaf moisture content (LMC) in winter wheat under irrigation treatments: W0 (no irrigation), W1 (45–65%), W2 (55–75%), W3 (65–85%), W4 (75–95%) of field capacity, and Z (irrigation and rainfall). Our findings show that the ratio stress index (RSI), with band combinations such as RSI7(650, 428), RSI8(663, 422), and RSI9(671, 450), performs better in tracking PMC and LMC, demonstrating high correlation and improved average prediction metrics for vegetation index (VI) models with R2, RMSE, and MAE of 0.838, 2.791, and 2.093 respectively, for LMC and VI-Tc input models with 0.850, 2.731, and 2.105 for PMC. Incorporating Tc into RSI models enhances prediction accuracy, increasing R² by up to 13.82% in the RSI-Tc-SVM-PMC model and decreasing RMSE and MAE by 15.89% and 18.33%, respectively. Therefore, a combination of RSI-Tc-SVM-ANN is recommended to monitor winter wheat moisture stress.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Agricultural drought is a significant limiting factor for agricultural production, with reports suggesting a probability greater than 80% for yield loss due to agricultural droughts1. As water resources become increasingly scarce, and agriculture accounts for 70% of freshwater withdrawal2. Effective water management practices, including soil water management, irrigation, and soil water conservation, are essential to sustain productive farming2. Remote sensing has demonstrated its effectiveness in tackling drought challenges in agriculture3,4,5. It offers the opportunity to monitor plant moisture content (PMC), leaf moisture content (LMC), soil moisture content (SMC)5, canopy temperature (Tc)4, photosynthesis, stomatal conductance4, chlorophyll levels6,7, and disease infection8 promptly, with high spatial and temporal resolution, showcasing its versatility.

Plant moisture is crucial for numerous biophysical and biochemical processes that regulate plant growth, development, and yield. Generally, PMC can be monitored in several ways, focusing on various parameters, including canopy moisture9, whole-plant moisture, leaf moisture, equivalent water thickness10, leaf relative water content, leaf fuel moisture11, and water potential12. Monitoring PMC through remote sensing has become a beneficial endeavor for alleviating moisture stress in farms, as this approach can identify moisture stress before other methods13. This feature is achieved by measuring canopy spectral reflectance and canopy temperature (Tc). The measured reflectance is further processed to form vegetation indices, which reveal essential information about a plant’s status based on its interaction with light within each spectrum.

Several approaches have been developed to form vegetation indices for monitoring PMC, utilizing a combination of wavelengths across the spectrum. It is widely reported that pigments, chlorophyll, and carotenoids14 influence the reflectance changes in the VIS. The NIR reflectance is influenced by leaf internal structure, canopy structure, plant age, and LAI, while the plant’s internal moisture influences the shortwave infrared (SWIR). From this backdrop, vegetation indices are being formed to monitor PMC and leaf moisture content (LMC).

Although VIS and NIR reflectance are viewed as indirect indicators of moisture stress in plants, these regions of the spectrum are recently being reported as capable of monitoring droughts in farmlands with equal effectiveness5,14,15,16. Sukhova et al.14,15,17, having conducted both laboratory and field experiments with pea and wheat plants in experiment pots, reported that ratio index (RI) (659, 553 nm), (613, 605 nm), and (670, 432 nm) and normalized red-green index (659, 553 nm) were suitable for monitoring soil drought and could identify changes in plant within four days of drought initiation, thus giving a new dimension of the use of VIS bands. Although these findings were significant, their work involved potted peas and wheat, which were not fully representative of typical farming conditions. Furthermore, their measurement of reflectance using a thermal camera necessitates an improved method for reflectance measurement. Li et al.18 then reported using UAV multispectral and hyperspectral data within the 400–1000 nm wavelength range for monitoring winter wheat and summer maize water content and yield prediction with ratio and normalized indices. Their work reported the importance of the VIS and novel indices for monitoring PMC. In their work, novel indices outperformed traditional indices. Since this work used a UAV system, which is more complicated and requires more competence to complete, and focused on only two growth stages (flowering and filling), a more straightforward and easier-to-use method that covers more growth stages will be a handy and safer approach; the spectroradiometer approach covers this scope and provides a more straightforward approach. Tian et al.19 also reported that the new indices performed better in predicting rice leaf nitrogen content. This implies that new band combinations for monitoring moisture stress in plants, both directly and indirectly, are possible.

Moreover, other than direct moisture stress monitoring, remote sensing has been employed to monitor moisture stress in plants indirectly; one such use is the application of thermal infrared cameras for monitoring plant canopy temperature4 which is an indirect method of moisture monitoring. According to the literature, as plants experience less available soil moisture, high temperature, and other environmental factors affecting moisture availability, they react by closing their stomata20. This leads to less transpiration and photosynthesis, thus increasing the surface leaf temperature21. Infrared thermal cameras detect the temperature change20, hence reflecting plants’ moisture status. Additionally, several other works have reported using machine learning models for predicting plants’ characteristics using remotely sensed data22,23,24,25. These combinations become a vital partnership for monitoring farmland plant moisture stress.

In an effort to improve the current status of water management in the face of the changing environments in which farmers farm, this work intended to form novel indices, concentrated in the VIS and NIR, from spectroradiometer-measured canopy reflectance and fuse them with canopy temperature that are capable of monitoring PMC and LMC at various growth stages of winter wheat. This will then enhance moisture stress monitoring by combining these approaches into a few indices and models and capitalizing on the high sensitivity of the VIS-NIR bands to stressors (including moisture stress), thereby preventing reliance on a single moisture stress monitoring approach and conventional water stress indices, which can sometimes be affected by environmental factors and fail to provide meaningful results. This approach ensures reliable monitoring of moisture stress, thereby providing a robust method for preventing moisture stress in winter wheat fields, guiding timely irrigation scheduling, and laying a scientific basis for decision-making in farmland water management.

Results

Canopy reflectance and water content of winter wheat across growth stages

Canopy spectral reflectance showed a continuous changing pattern across growth stages (Fig. 1). Notably, as the growth progressed, there was an increase in reflectance in the VIS and SWIR bands, while the NIR bands exhibited a decrease in reflection. This trend suggests that spectral reflectance is influenced by the moisture content, age, and growth stage of winter wheat, making it a valuable tool for monitoring moisture stress in winter wheat plants. As observed, the highest NIR reflectance was recorded at the booting stage and continued to decrease as the growth stages progressed up to maturity (Fig. 1). After the flowering stage of winter wheat, the moisture content continued to decline across all treatments, despite SMC showing both increasing and decreasing trends during the same period. This is a noticeable trend as plants mature. The grains, leaves, and stems generally lose moisture as plants senesce with age.

Novel vegetation index and canopy temperature (Tc) correlation with plant moisture content (PMC), and leaf moisture content (LMC)

The two novel indices and Tc showed a significantly negative correlation with PMC and LMC at various growth stages and throughout the growing season. Most importantly, different indices exhibited the highest correlations at different stages of growth. As shown in Table 1 (correlation results), the novel indices outperformed the published indices further for monitoring moisture content in wheat. SRWI (R = 0.86***), RSI10(600, 739) (R = 0.88***), and NDSI1(499, 764) (R = 0.89***) had the highest overall correlation with PMC for their respective index types. RSI had the best growth stage performance with RSI9(671, 450) (R = 0.45ns) at elongation, RSI7(650, 428) (R = 0.71***) at booting, RSI6(530, 764) (R = 0.83***) at flowering and RSI8(663, 442) (R = 0.93***) at the ripening stages. NDSI9(506, 1100) (R = 0.73***) had the highest correlation at the filling stage, while WBI (R = 0.5*) and MSI (R = 0.72***) had the highest correlations at heading and dough stages, respectively. With LMC, RSI had the best growth stage performance, having had the highest correlation coefficient at elongation (R = 0.66**), flowering (R = 0.74***), filling (R = 0.82***), dough (R = 0.89***), and ripening (R = 0.87***) in addition to the overall growth cycle data (R = 0.69***). These performances suggest that the new indices are more suitable for monitoring winter wheat moisture stress than the published indices in our study. The corresponding p-values and significance are better indicated in Table 1 and its note.

Correlations were conducted by treatment to assess the suitability of the new indices further. Interestingly, as evidenced in Table 2, there were highly significant correlations between PMC and various index types. At the treatment level, the Pearson correlation coefficient for all indices with PMC ranged from 0.93 to 0.98, with the strongest correlation (RSI7 (R = 0.98***)) observed in the W4 treatment (significance in Table 2). The LMC correlations indicated that RSI achieved the best performance overall, with the highest R of 0.87*** in W2. A strong correlation was also found between Tc and PMC across treatments. These correlation results suggest that these new indices can potentially monitor moisture stress characteristics in winter wheat fields.

Machine learning prediction of plant moisture content (PMC)

To evaluate the indices’ predictive abilities, four machine learning models — random forest (RF), partial least squares regression (PLSR), support vector machine (SVM), and artificial neural network (ANN)- were fitted to the data. 70% (104) of the data was used for model training, while 30% (40) was used for testing the models. This 30% data was not used in model training and was set aside for model testing. For model tuning and parameterization, we employed the cross-validation (k = 10) and grid search method, where the models were tuned, and the best parameter combinations that produced the lowest RMSE were selected. This ensures that the best possible parameters are utilized for modelling.

Firstly, models were built with only vegetation indices as the input data. With the VIs as the only input data, the RSI-ANN model achieved the best performance, yielding an R² of 0.849, RMSE of 2.736, and MAE of 2.131. The NDSI-ANN model yielded the second-best results, with an R² of 0.844, RMSE of 2.784, and MAE of 2.284. With the published indices, the best performance was achieved by the PLSR model, yielding an R² of 0.831, an RMSE of 2.895, and an MAE of 2.231 (Table 3). Our work shows that the novel indices outperform the notable water stress monitoring indices. The Tc was added as input data to the models to better explore the benefits of multi-source data fusion for these indices in stress monitoring. This addition generally improved the performance of the models and indices in predicting PMC. With this inclusion, the RSI-ANN model had an R2 of 0.850, RMSE of 2.726, and MAE of 2.078 (Fig. 2), the NDSI-ANN model achieved an R2 of 0.842, RMSE of 2.803, and MAE of 2.293 (Fig. 3) and the ANN and published VI model had an R2 of 0.866, RMSE of 2.577, and MAE of 1.820 (Fig. 4). In addition, incorporating Tc into prediction models improved performance over the metrics presented in Table 3.

Figure 2 presents the prediction metrics of machine learning using RSI-Tc as input data to predict PMC. Notably, there are good prediction metrics across all models. As revealed, error metrics are also appreciable.

Shows the PMC model testing metrics for the ratio stress index (RSI) combined with Tc as input data for machine learning models. a is the random forest model, b is the partial least squares model, c is the support vector machine model, and d is the artificial neural network model. Error metrics are presented in percentage. The green line is the regression line, while the red dashed line is the 1:1 ratio line. The higher point density indicates the regions with more samples, while the proximity to the regression line indicates model accuracy.

Shows the PMC model testing metrics for the normalized drought stress index (NDSI) combined with Tc as input data for machine learning models. a is the random forest model, b is the partial least squares model, c is the support vector machine model, and d is the artificial neural network model. Error metrics are presented in percentage. The green line is the regression line, while the red dashed line is the 1:1 ratio line. The higher point density indicates the regions with more samples, while the proximity to the regression line indicates model accuracy.

Shows the PMC model testing metrics for the published indices combined with Tc as input data for machine learning models. a is the random forest model, b is the partial least squares model, c is the support vector machine model, and d is the artificial neural network model. Error metrics are presented in percentage. The green line is the regression line, while the red dashed line is the 1:1 ratio line. The higher point density indicates the regions with more samples, while the proximity to the regression line indicates model accuracy.

Figure 5 presents the variable importance for the random forest model. In the RSI model, RSI9, RSI10, and RSI6 were the top three contributing indices, while the Tc was the fourth most important variable (Fig. 8a). With the NDSI model, the contribution of Tc is not well pronounced, though it increased the overall prediction accuracy of the model. The published indices model saw the NDVI, SRWI, WI, OSAVI, and Tc as the top contributing variables.

ML prediction performance of LMC

The LMC prediction model, using the new indices as input data, further demonstrated a promising performance compared to the published indices, with the SVM model combined with RSI producing the highest R² of 0.824, RMSE of 2.910, and MAE of 2.111 (Table 3). The SVM and NDSI model achieved an R² of 0.732, an RMSE of 4.165, and an MAE of 2.701 (Table 3), whereas the published indices and RF model achieved an R² of 0.752, an RMSE of 3.454, and an MAE of 2.299. Again, the RSI achieved the best performance. The VIs combined with Tc further improved the performance of the models, as presented in Table 6; Figs. 6, 7 and 8. The SVM-RSI-Tc model R2 increased to 0.851 (3.338%), while RMSE reduced to 2.673 (8.148%) and MAE to 2.075 (1.677%). The SVM-NDSI-Tc model increased the testing R2 to 0.770 (5.149%), reduced RMSE to 3.323 (7.313%), and MAE to 2.424 (4.634%). RF, Tc, and published indices model improved the prediction R2 by 0.792 (5.384%), while also reducing RMSE and MAE by 3.160 (8.52%) and 2.237 (2.669%), respectively. Index-wise, the RSI-Tc combination achieved the best performance in predicting LMC, while the SVM model had the best performance among ML models. The better performance of the ANN and SVM models can be attributed to their ability to model complex, nonlinear relationships between the target and predictor variables, a feature that is highly present in spectral vegetation indices and the PMC relationship.

Presents the RSI-Tc LMC prediction metrics. a is the random forest model, b is the partial least squares model, c is the support vector machine model, and d is the artificial neural network model. Error metrics are presented in percentage. The green line is the regression line, while the red dashed line is the 1:1 ratio line. The higher point density indicates the regions with more samples, while the proximity to the regression line indicates model accuracy.

Illustrates the NDSI-Tc LMC prediction models metrics, where a is the random forest model, b is the partial least squares model, c is the support vector machine model, and d is the artificial neural network model. Error metrics are presented in percentage. The green line is the regression line, while the red dashed line is the 1:1 ratio line. The higher point density indicates the regions with more samples, while the proximity to the regression line indicates model accuracy.

Shows the published indices-Tc LMC prediction metrics, where a is random forest, b is partial least squares regression, c is the support vector machine model, and d is the artificial neural network model. The red dashed line is the 1:1 ratio line, while the green line is the regression line. The higher point density indicates the regions with more samples, while the proximity to the regression line indicates model accuracy.

Discussion

Agricultural drought has become a key challenge for winter wheat production. Monitoring and preventing its occurrence promptly in farmlands are crucial for improved wheat production. This can be effectively achieved by remote sensing. The combination of different bands across the spectrum has proven effective in monitoring various biophysical and biochemical characteristics of plants in diverse environments and conditions.

In our work, we examined the feasibility of band combinations (vegetation indices) between the NIR and VIS, with the VIS bands focused on the blue and green bands. Our work revealed that the combination of bands between VIS and NIR (400–1100 nm) and VIS-VIS bands (400–671 nm) ranges can effectively monitor winter wheat moisture stress at critical growth stages. These results are consistent with findings reported in other works14,15,16,17,18,26,27, who reported that VIS indices performed better in monitoring the canopy water content of summer maize compared to traditional water-sensitive indices.

Although this region has been mainly linked to photosynthesis15 and pigment-related characteristics, it is also reported that photosynthesis, chlorophyll, and pigments are affected by water stress, which subsequently reduces the absorption prowess of chlorophyll and other leaf pigments, thereby increasing reflectance in the visible region28,29,30. This makes this spectral region very sensitive to changes in plant moisture.

As moisture stress intensifies, it triggers physiological responses in the internal structures of leaves, resulting in changes in spectral response to incoming radiation. These interactions can further express stress levels in winter wheat30. With reports that the VIS presents the highest correlation coefficient in winter wheat compared to other spectral regions31, blue and green bands have been less frequently reported for monitoring winter wheat moisture stress. However, there are reports of their use for disease detection in plants and yield prediction32,33,34. An et al.6 reported the suitability of visible bands in predicting rice’s chlorophyll content and their effect on canopy spectral reflectance.

Our work reveals that ratio and normalized band selections in the VIS and NIR bands range are essential tools for monitoring moisture stress in winter wheat at critical growth stages (Figs. 2 and 3). As shown in Table 2, apart from the elongation stage, there is a significant correlation between the calculated indices and PMC, indicating the sensitivity of both indices to moisture content during reproductive growth stages, consistent with other reported findings27. Like other reported indices, the created indices can be employed as a key monitoring tool for water stress monitoring in winter wheat from the booting to harvest stages. Interestingly, the RSI demonstrated a better growth stage monitoring ability for PMC, with RSI calculated using two VIS bands (RSI7, RSI8, and RSI9) exhibiting the best performance. The ability of these indices to predict winter wheat’s moisture content has a positive implication for winter wheat farming, as it ensures timely stress detection and precision irrigation control, thereby preventing moisture stress to winter wheat at critical growth stages.

At the treatment level (Table 2), these indices show significant correlation with PMC. These highly substantial correlations confirm that these indices can be used at treatment levels to monitor water stress, ensuring timely irrigation scheduling. In addition to the superior growth stage correlations, the RSI, when used as input data for the SVM model, further produced the best performance in predicting the PMC of winter wheat (Table 3). In conclusion, the better performance of the new indices over the published indices validates the need for further applying new band combinations to monitor moisture stress in winter wheat fields.

When Tc was included as input data for PMC prediction, the SVM showed notable improvements, with the best performance characterized by increased R2 across all input data and enhanced accuracy. With the RSI-Tc, there was an increase of 13.820% in R2, a decrease of 15.890% and 18.327% in RMSE and MAE, respectively. Although the published indices-ANN model obtained the highest prediction accuracy (Table 3), the RSI and NDSI closely follow the trend of improved performance by the SVM across all indices, putting it in strong contention for consideration as a formidable ML model for moisture stress monitoring in winter wheat.

LMC plays a significant role in plant growth and development, as it controls physiological processes such as photosynthesis, transpiration, nutrient uptake, and PMC control35 through its regulation of the stomata. Canopy reflectance from winter wheat canopies, spanning the VIS-SWIR regions, has been reported to monitor changes in plant water status36. Due to this critical role, our work endeavored to monitor LMC using novel indices and compared their performance with those of notable moisture content monitoring indices. As presented in Table 2, there is a strong correlation between LMC and all three types of indices, with the RSI exhibiting the best treatment-wise performance. At individual growth stages (Table 1), the RSI exhibits its best performance with RSI7, RSI8, and RSI9, which are calculated from two VIS bands that present the best performance. This performance trend is also seen at the treatment level (Table 2). With the prediction models, there is an acceptable output from the four ML models presented in this work for predicting LMC. With input data of vegetation indices (Table 5), other than PLSR-published indices (R2 = -3.105) and NDSI-ANN models (R² = 0.489), all other combinations produced an R² ≥ 0.578, with the RSI combinations showing superior performance. Comparatively, the LMC prediction performance was less accurate than that of the PMC prediction. This outcome is because other parts of winter wheat (stems and spikes) also affect canopy reflectance beyond the leaf level. This result was also reported by Zhang et al.37. With these outputs, it can be concluded that the VIS is a crucial tool for monitoring winter wheat moisture stress due to its outstanding performance in tracking LMC in winter wheat fields.

The better performance of the RSI and NDSI (generally VIS-NIR bands) over the conventional vegetation indices used in this work has been reported in literature and linked to some physiological and biochemical plant features. Plant chlorophyll and pigments are sensitive to plant moisture and are affected by the slight changes in internal moisture content and they are key contributors to reflectance in the VIS38. NIR reflectance is influenced by the by leaf internal structures, canopy coverage, and general plant health, which are highly sensitive to plant moisture. These mentioned physiological parameters react to stress at a very fast pace. These regions also responsd to other stressors39. These conditions provide an extra advantage over the SWIR bands, which mostly rely on acute moisture stress. This leads to better performance of the VIS-NIR bands in moisture stress monitoring.

The varying sensitivity of vegetation indices to specific plant biophysical features has also been reported in the literature. This phenomenon has been linked to several conditions and characteristic features, ranging from environmental factors (solar angle, soil background), plant features (canopy structure, leaf angle inclination, leaf area index, leaf internal moisture and cell structures, as well as leaf chlorophyll and pigments), and viewing geometry. Prudnikova et al.40 reported that soil background and soil variability influence VIS and NIR canopy spectral reflectance at the early growth stages of winter wheat. Also, at early growth stages, background materials influence spectral reflectance41. These influences are reduced with the growth and proper coverage of the plant canopy. With the plant canopy structure, the leaf area index, canopy coverage, and leaf inclination angles directly influence the amount of solar radiation that is intercepted and reflected42. These underlying factors, in addition to plant health, internal moisture, and structural makeup, play a crucial role in the varying sensitivity of vegetation indices to moisture content in plants across different growth stages.

Agricultural drought can harm winter wheat, but early detection and prompt remediation can help mitigate damage. Specifically, drought leads to a decrease in soil moisture, reducing plant water content43. These effects trigger several physiological changes in plants, varying according to the drought’s duration and severity. Fortunately, these changes can be detected using various remote sensing tools, including ground-based spectrometers and thermal imagers21. A reduction in plant moisture triggers responses that impact LAI, photosynthesis, cell health, chlorophyll levels, and stomatal function. As plants experience moisture stress, they adjust their stomata to limit water loss, which raises the leaf surface temperature—detectable by thermal imagers31. This temperature change results from both internal plant conditions and environmental factors, expanding the application of this technology in moisture stress monitoring. Since both spectral reflectance and canopy temperature reflect moisture levels in winter wheat, combining these measurements improves moisture stress detection more than using either method alone, as shown in our study. We evaluated the impact of Tc as input data in models using three types of indices, presented in Table 4. In the LMC prediction models, the SVM demonstrated the most significant positive influence, with all inputs contributing to an increase in R2 and a decrease in the error metrics. RF also had a significant effect, with the highest R2 increase of 16.426% and the highest reduction in RMSE by 15.808%. The index type with the most consistent performance across all models was the NDSI. Results indicate an increase in R², ranging from 2.209% to 16.426%, while the error was reduced by 1.649% to 15.808%. It can then be concluded that the Tc inclusion in the LMC prediction models had the most significant influence on the SVM and NDSI performance, with the RSI combined with PLSR and ANN exhibiting the poorest performance. The use of canopy temperature and its derivative parameters as a proxy for moisture stress in plants, and their application in controlling irrigation, has also been reported by other studies21,44. We therefore conclude that including Tc in VIs ML models for monitoring plant moisture stress yields a better prediction accuracy. Still, care must be taken to select the best match between model and input types.

Machine learning models have become a valuable tool for modelling remotely sensed data to monitor plants’ biophysical and biochemical characteristics due to their ability to learn the complex interactions and relationships between target(s) and predictor(s) variables23,45. In our work, we applied four machine learning models to predict the PMC of winter wheat and further validated the models. Model evaluation results indicate that the ANN model using published indices-Tc as input achieved the best performance, with R², RMSE, and MAE values of 0.866, 2.577, and 1.820, respectively, for PMC simulation, and the ANN-RSI-Tc combination achieved R², RMSE, and MAE values of 0.850, 2.726, and 2.078, respectively. (Table 3; Fig. 2d). With the vegetation indices as input, the ANN model produced the best PMC simulation across all input types (Table 3). The PMC simulation performance metrics (averaging the model with only VIs and VIs-Tc) showed that the highest R2 was achieved by the ANN model across inputs 0.843, 0.850, and 0.847, respectively, for NDSI, RSI, and the published indices, respectively. The performance of LMC models exhibited better SVM performance, as measured by both individual input data and the average R² for all data types and models used for modeling. The SVM-RSI-Tc combination achieved the best metrics with R2, RMSE, and MAE of 0.851, 2.673, and 2.075, respectively. These outstanding performances of the ML models in predicting PMC and LMC are consistent with findings from other studies18,25,46. These findings have significant implications for monitoring moisture stress in winter wheat.

Conclusion

Moisture stress in winter wheat has a far-reaching impact on growth, development, yield, and food security. In this work, we reported two approaches (VIs and VIs-Tc) to alleviate winter wheat moisture stress through direct monitoring of plant moisture and leaf moisture through canopy reflectance and its derived vegetation indices, and indirectly monitoring plant canopy temperature with infrared thermal imagers, and fusing the multi-source data in ML models. We can safely conclude that the indices (RSI and NDSI) are valuable tools for monitoring moisture stress in winter wheat fields. As reported, the RSI, with prominent VIS band combinations of RSI7(650, 428), RSI8(663, 422), and RSI9(671, 450), demonstrated a good ability to monitor PMC and LMC across different growth stages and treatments. The NIR and VIS band combinations (400 –600 nm) further showed strong potential for detecting moisture stress in winter wheat fields, a feature that is less reported. Fusing these VIS-derived indices with canopy temperature as input data for ML models improves the accuracy of ML model predictions. These improvements lay scientific foundations for stress monitoring and irrigation control in winter wheat fields, thereby alleviating moisture stress.

Limitation of the study

It is worth mentioning that this work covered one year and a single experiment site. Future work will focus on assessing these indices and fusion methods across different sites and years to further consolidate their valuable contributions to monitoring moisture stress in winter wheat fields.

Materials and methods

Study site and treatment

The research was conducted at the Qiliying Comprehensive Experimental Base, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (35°18′11′′N and 113°55′34′′E), located at an elevation of 81 m above sea level. The site experiences an average annual rainfall of 573.4 mm, with approximately 70% of the rainfall occurring during the summer. The yearly average temperature is 14 °C, and the annual solar radiation is 4900 MJ m− 2 yr− 1, with 189–240 frost-free days per year. The experimental soil has a bulk density of 1.46 g/cm3, a field capacity of 24.77%, and a porosity of 41.17% at a soil depth of 0–60 cm.

Winter wheat was planted on October 18, 2024, with row spacing of 20 cm and a seeding rate of 227.27 kg per hectare and was harvested on May 29, 2025. Irrigation was applied using drip lines spaced 40 cm apart with emitters spaced 30 cm apart. Six irrigation treatments were used: W0 (no irrigation), W1 (45–65% soil moisture), W2 (55–75% soil moisture), W3 (65–85% soil moisture), W4 (75–95% soil moisture), with plot sizes of 3.4 m x 2.03 m, and Z with 2 m x 2 m, representing normal farmers’ irrigation and rainfall. The soil moisture levels were intended to create varying moisture availability to plants, thereby introducing varying stress levels, which could trigger varying physiological responses from the plants47,48. These physiological responses further influence canopy reflectance, which can be captured by remote sensing equipment49. Each treatment had three replicates. Soil moisture within the 0–60 cm depth was monitored gravimetrically, and irrigation amounts were calculated based on the difference between the current soil moisture and the target maximum soil moisture level for each treatment. An initial irrigation of 227.27 mm was applied before sowing to provide moisture for early growth and overwintering, along with a compound fertiliser.

Irrigation treatments commenced during the regreening period on March 6, 2025. Fertiliser was applied according to local recommendations for the research location. Irrigation was measured using flow meters. The Z treatment received a total of 446.95 mm of rainfall and irrigation during the treatment period. The total irrigation amounts per treatment are: 0 mm, 260.06 mm, 276.28 mm, 362.53 mm, and 372.69 mm for W0, W1, W2, W3, and W4, respectively, excluding the pre-sowing irrigation.

Spectral reflectance, canopy temperature, and plant moisture data collection

Canopy spectral reflectance was measured using a handheld spectroradiometer, the PSR + 3500 (Spectral Evolution Inc., Lawrence, MA, USA), with a wavelength range of 350–2500 nm, at a height of 1 m, providing a 25° field of view above the canopy on clear-sky days with little or no wind interference from 10:30 am to 11:30 am Beijing Time on clear sky days with little or no winds. Before each measurement, the instrument was calibrated using a reference plate with 99% reflectance, and this calibration was repeated every 15 min. The spectroradiometer has resolutions of 3 nm at 700 nm, 8 nm at 1500 nm, and 6 nm at 2100 nm. The spectroradiometer resampled each measurement to produce 2151 narrow bands as the final output. The instrument was fitted with a fore-optic fibre cable for reflectance measurement6. The instrument was set to average twenty-five scans per measurement, and every plot was scanned at four different points and averaged to represent the reflectance of the plot per measurement day. Reflectance measurements were done on March 17, 25, April 2, 10, 18, 26, and May 4 and 12.

Canopy temperature was measured between 11:30 am and 12:30 pm Beijing Time using an infrared thermal camera (InFRec G100, NEC, Tokyo, Japan)4. This measurement was performed at a vertical distance of 1 m from the target (canopy) at a 45° angle immediately following the daily spectral measurement on data collection days. The InFRec G100 can provide the average temperature for target areas within the field of view without needing further calculations. It was programmed to have five focus points and give the average temperature for each focus point. Emissivity was set at 0.98, and the InFRec G100 was calibrated before daily measurements. The equipment performed periodic self-calibrations during the measurement. Measurements were made at full canopy closure points.

Five wheat plants, which included all tillers from each germinated seed, were collected and placed in a Ziplock plastic bag for measurement of their moisture content (PMC). An additional plant leaf (including all tillers from a single germinated seed) was collected for LMC measurement on all data collection days. These plants were collected from the second rows on either side of the plots, maintaining a distance of 50 cm from the beginning of each row. Both leaf and plant moisture samples were collected from the same points on specific data collection days and alternately between the two rows. This was done to prevent losing all plants at a particular point and maintain a good canopy cover, which will enable the continuation of the experiment. They were weighed fresh, initially dried in an oven at 105 °C for 30 min, and then dried at 80 °C until a constant weight was achieved to obtain the dry weight. Soil samples were simultaneously collected in the 0–60 cm layers to calculate soil moisture50. The average soil moisture for all layers was considered the soil moisture within the root zone and used as the basis for irrigation calculation. PMC, LMC, and gravimetric soil moisture content (SMC) were calculated using the following two Eqs. (1–3):

Where PFW, PDW, LFW, LDW, WS, and DS are fresh plant weight (g), dry plant weight (g), fresh leaf weight (g), dry leaf weight (g), wet soil (g), and dry soil (g), respectively.

Spectral band selection for index calculation and index selection for modelling

Firstly, the visible and near-infrared bands have been reported as sensitive bands to both biotic and abiotic plant stressors and have been used to identify and differentiate these stresses51. For example, Koh et al.52 reported the use of VIS and NIR bands for classification of drought-induced physiological changes in plant colouration, while Vásquez et al.53 reported that there is a contrasting interaction with radiation between the VIS and NIR. The chlorophyll content in healthy leaves absorbs more incident rays in the VIS while reflecting incident rays in the NIR. As plant moisture reduces, chlorophyll and other plant pigments are also affected and are thereby reduced39. These changes affect leaf internal and canopy structures, thereby influencing the reflection in incoming incident rays. These changes are captured by remote sensing and analysed to reflect the status of the plants. Fully harnessing the potential of these regions will lay a solid technical foundation for monitoring plant stress promptly and developing low-cost remote sensing devices54. Based on these underlying phenomena, our work focused on these regions of the spectral wavelength to monitor moisture stress in winter wheat.

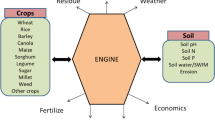

To begin, all two-band combination indices were generated18, which included all bands in the VIS and NIR regions. These band combinations were used to calculate vegetation indices, which were correlated with PMC. The highest R² from band combinations within the VIS and NIR was selected, thereby revealing the most sensitive bands for monitoring PMC. These bands were further used for monitoring leaf moisture content (LMC). The goal for these band selections was to select band combinations between VIS (blue, green) and VIS (red) bands. These combinations will highlight the significance of these bands (VIS bands) in monitoring moisture stress in farmlands. The following band combinations focused on the VIS (blue, green) and NIR bands. These combinations will then highlight the importance of the blue and green electromagnetic spectrum region in moisture monitoring stress in combination with the NIR. These highlights will further extend the VIS moisture stress monitoring ability beyond the traditionally recognized red and/or red-edge regions of the spectrum. This revealed the best band combinations for index formation. Two index types are used in this work. One type used the normalized two-band combination between NIR and VIS bands (Eq. 4), and the other used the ratio between two bands in Eq. (5) (VIS-VIS and VIS-NIR). The normalized drought stress index (NDSI) utilized the normalized formula, while the ratio stress index (RSI) employed the ratio formula.

The two formula types were:

Where Band1 and Band2 are random wavelengths within the VIS and NIR.

Based on the coefficient of determination (R2) and sorting out as explained above for the selection criteria, the best wavelength combinations were selected and listed in Table 5.

Normalised drought stress index (NDSI) and ratio stress index (RSI). The reflectance at the two specified wavelengths was used to calculate the indices, with the first corresponding to Band 1 and the second to Band 2.

Three feature selection algorithms were used to select the best indices for model building. They are the recursive feature elimination (RFE), the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regression, and the random forest algorithm (RFA). RFE is a feature selection algorithm that gradually removes the less essential variables while maintaining the most important ones55. LASSO regression applies the L1 regularisation to penalise the absolute size of the coefficient, thus shrinking some to zero and performing feature selection, and preventing overfitting. RF is an ensemble-based approach that uses variable importance to rank features based on the scores from individual trees. After each feature selection method was completed, all VIs for a specific index type were ranked from the most important to the least important for the target variable. The first set of selected indices was those selected by the three feature selection methods in the top seven. Then, the balance indices were selected from VIs that were selected at least twice by two of the three feature selection methods in their top ten ranked VIs. The selected indices were used as input data for model building.

To further assess the performance of the new band combination indexes, some previously used indices for moisture stress monitoring were calculated and used in this work. These indices and their calculation formulas are presented in Table 6. All previously published indices were used in model building.

Machine learning models

This work used four machine learning models: partial least squares regression (PLSR), RF, support vector machines (SVM), and artificial neural networks (ANN) to predict PMC and SMC. A statistical modelling method called partial least squares regression (PLSR) identifies latent components accounting for variation in predictors and responses. Because PLSR is so versatile (e.g., it makes few assumptions and handles collinear variables effectively), it is invaluable as a data exploration approach63. Tin Kam Ho developed the non-parametric, supervised, ensemble machine learning algorithm known as RF regression, which uses a set of decision trees to generate predictions. RF is a well-liked option for regression and classification tasks, as it uses ensemble learning techniques to produce precise and dependable predictions by employing multiple decision trees instead of a single model. RF’s primary goal is to create a “forest” by merging multiple decision trees, typically through bootstrap aggregation, also known as “bagging.” One of RF’s main advantages is that it can withstand overfitting, even with many features64. SVM is another famous machine learning model that has proven to be a good fit for modelling plant characteristics in remote sensing. Some researchers have reported its better performance23. ANNs are supervised, non-parametric machine learning techniques that mimic how the human brain processes information to model complex issues for decision-making or prediction. Neural networks are superior to alternative regression models in several ways. These include their ability to represent known or non-linear correlations between variables, resilience to noisy inputs, capacity to generalize input variables, and absence of variable-specific assumptions5.

For model tuning parameters, we implemented the cross-validation and grid search approach as further explained by An et al.6. Model performance was assessed using the root mean square error (RMSE), mean absolute error (MAE), and the coefficient of determination (R²), which were calculated using Eqs. (6–8), respectively.

Where RMSE is the root mean square error, MAE is the mean absolute error, R2 is the coefficient of determination, n is the total number of observations in the dataset, yi is the observed value at sample i (runs from 1 to n), ∑ indicates adding up all terms from i = 1 to i = n, \(\widehat {{{{\text{y}}_{\text{i}}}}}\) is the predicted value of the dependent variable at the i-th observation, \({{\bar {y}}}\) is the mean of the observed values, \(\overline {{{{\hat {\rm y}}}}}\) is the mean of the predicted values, |.| is the absolute value.

All data were analysed using R programming (R Core Team, 2023, Vienna, Austria) and OriginPro, Version 2025 (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA) for plotting graphs and statistical analysis.

Data availability

All data will be available upon reasonable request through the corresponding authors.

References

Leng, G. & Hall, J. Crop yield sensitivity of global major agricultural countries to droughts and the projected changes in the future. Sci. Total Environ. 654, 811–821. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.10.434 (2019).

Naganjali, K. et al. Revamping water use in agriculture: techniques and emerging innovations. J. Sci. Res. Rep. 30, 1055–1066. https://doi.org/10.9734/JSRR/2024/V30I72215 (2024).

Patiluna, V. et al. Using hyperspectral imaging and principal component analysis to detect and monitor water stress in ornamental plants. Remote Sens. (Basel). 17, 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17020285 (2025).

Ma, S. et al. Water deficit diagnosis of winter wheat based on thermal infrared imaging. Plants 13, 745. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants13030361 (2024).

Vahidi, M., Shafian, S. & Frame, W. H. Precision soil moisture monitoring through drone-based hyperspectral imaging and PCA-driven machine learning. Sensors 25, 856. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25030782 (2025).

An, G. et al. Using machine learning for estimating rice chlorophyll content from in situ hyperspectral data. Remote Sens. (Basel). 12, 3104. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs12183104 (2020).

Haboudane, D., Miller, J. R., Tremblay, N., Zarco-Tejada, P. J. & Dextraze, L. Integrated narrow-band vegetation indices for prediction of crop chlorophyll content for application to precision agriculture. Remote Sens. Environ. 81, 416–426. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0034-4257(02)00018-4 (2002).

Ashraf, A. et al. Remote sensing as a management and monitoring tool for agriculture: potential applications. Int. J. Environ. Clim. Change. 13, 324–343. https://doi.org/10.9734/ijecc/2023/v13i81957 (2023).

Ustin, S. L., Riaño, D. & Hunt, E. R. Estimating canopy water content from spectroscopy. Isr. J. Plant. Sci. 60, 9–23. https://doi.org/10.1560/IJPS.60.1-2.9 (2012).

Elsherif, A., Gaulton, R. & Mills, J. Estimation of vegetation water content at leaf and canopy level using dual-wavelength commercial terrestrial laser scanners. Interface Focus 8, 96. https://doi.org/10.1098/RSFS.2017.0041/ASSET/28D0DAB9-D91E-4102-B45A-8B8791F7A6D6/ASSETS/GRAPHIC/RSFS20170041F12.JPEG (2018).

Zhang, F. & Zhou, G. Estimation of vegetation water content using hyperspectral vegetation indices: a comparison of crop water indicators in response to water stress treatments for summer maize. BMC Ecol. 19, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12898-019-0233-0/FIGURES/4 (2019).

Holtzman, N. M. et al. L-Band vegetation optical depth as an indicator of plant water potential in a temperate deciduous forest stand. Biogeosciences 18, 739–753. https://doi.org/10.5194/BG-18-739-2021 (2021).

Brown, D. & Poole, L. Enhanced Plant Species and Early Water Stress Detection Using Visible and Near-Infrared Spectra 765–779 (Springer, 2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-9819-5_55

Sukhova, E. et al. Complex analysis of the efficiency of difference reflectance indices on the basis of 400–700 Nm wavelengths for revealing the influences of water shortage and heating on plant seedlings. Remote Sens. (Basel). 13, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs13050962 (2021).

Sukhova, E. et al. New normalized difference reflectance indices for estimation of soil drought influence on pea and wheat. Remote Sens. (Basel) 14, 569. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs14071731 (2022).

Sukhova, E. et al. Modified photochemical reflectance indices as new tool for revealing influence of drought and heat on pea and wheat plants. Plants 11, 745. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants11101308 (2022).

Sukhova, E. et al. Broadband normalized difference reflectance indices and the normalized red–green index as a measure of drought in wheat and pea plants. Plants 14, 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14010071 (2025).

Li, Z. et al. Novel spectral indices and transfer learning model in Estimat moisture status across winter wheat and summer maize. Comput. Electron. Agric. 229, 123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2024.109762 (2025).

Tian, Y. C. et al. Assessing newly developed and published vegetation indices for estimating rice leaf nitrogen concentration with ground-and space-based hyperspectral reflectance. Field Crops Res. 120, 299–310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fcr.2010.11.002 (2011).

Ihuoma, S. O. & Madramootoo, C. A. Recent advances in crop water stress detection. Comput. Electron. Agric. 141, 267–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2017.07.026 (2017).

Van Zyl, J. L. Canopy temperature as a water stress indicator in vines. South. Afr. J. Enol. Viticulture 7, 785. https://doi.org/10.21548/7-2-2326 (2017).

Zhang, Z. et al. Inversion of crop water content using multispectral data and machine learning algorithms in the North China plain. Agronomy 14, 586. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy14102361 (2024).

Zhuang, T. et al. Coupling continuous wavelet transform with machine learning to improve water status prediction in winter wheat. Precis. Agric. 24, 2171–2199. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11119-023-10036-6 (2023).

Wang, Y. et al. Estimating maize leaf water content using machine learning with diverse multispectral image features. Plants 14, 973. https://doi.org/10.3390/PLANTS14060973 (2025).

Wu, Y. et al. Combining machine learning algorithm and multi-temporal temperature indices to estimate the water status of rice. Agric. Water Manag. 289, 108521. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.AGWAT.2023.108521 (2023).

El-Hendawy, S. E. et al. Potential of the existing and novel spectral reflectance indices for estimating the leaf water status and grain yield of spring wheat exposed to different irrigation rates. Agric. Water Manag. 217, 356–373. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.AGWAT.2019.03.006 (2019).

Zhou, Z., Ecol, B., Zhang, F. & Zhou, G. Estimation of vegetation water content using hyperspectral vegetation indices: a comparison of crop water indicators in response to water stress treatments for summer maize. BMC Ecol. 19, 18–18. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12898-019-0233-0 (2019).

Zygielbaum, A. I., Arkebauer, T. J., Walter-Shea, E. A. & Scoby, D. L. Detection and measurement of vegetation photoprotection stress response using PAR reflectance. Isr. J. Plant. Sci. 60, 37–47. https://doi.org/10.1560/IJPS.60.1-2.37 (2012).

Genc, L. et al. Determination of water stress with spectral reflectance on sweet corn (Zea Mays L.) using classification tree (CT) analysis. Zemdirbyste 100, 81–90. https://doi.org/10.13080/z-a.2013.100.011 (2013).

Skendžić, S., Zovko, M., Lešić, V., Pajač Živković, I. & Lemić, D. Detection and evaluation of environmental stress in winter wheat using remote and proximal sensing methods and vegetation indices—a review. Divers. (Basel). 15, 481. https://doi.org/10.3390/d15040481 (2023).

Gao, C. et al. Estimation of canopy water content by integrating hyperspectral and thermal imagery in winter wheat fields. Agronomy 14 , 2569. https://doi.org/10.3390/AGRONOMY14112569 (2024).

G, R. & Srinivasan, M. Detection and Estimation of damage caused by thrips thrips tabaci (Lind) of cotton using hyperspectral radiometer. Agrotechnology 3, 896. https://doi.org/10.4172/2168-9881.1000123 (2014).

Pourazar, H., Samadzadegan, F. & Dadrass Javan, F. Aerial multispectral imagery for plant disease detection: radiometric calibration necessity assessment. Eur. J. Remote Sens. 52, 17–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/22797254.2019.1642143/ASSET/275A0F3F-1B23-41E4-A6BA-AC156898F845/ASSETS/IMAGES/TEJR_A_1642143_ILG0002.JPG (2019).

Cao, Q. et al. Improving in-season estimation of rice yield potential and responsiveness to topdressing nitrogen application with crop circle active crop canopy sensor. Precis Agric. 17, 136–154. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11119-015-9412-Y/METRICS (2016).

Li, C. et al. Hyperspectral Estimation of winter wheat leaf water content based on fractional order differentiation and continuous wavelet transform. Agronomy 13, 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/AGRONOMY13010056 (2022).

Zhang, J. et al. Comparison of new hyperspectral index and machine learning models for prediction of winter wheat leaf water content. Plant. Methods 17, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/S13007-021-00737-2/FIGURES/10 (2021).

Zhang, C., Liu, J., Shang, J. & Cai, H. Capability of crop water content for revealing variability of winter wheat grain yield and soil moisture under limited irrigation. Sci. Total Environ. 631-632, 677–687. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.03.004 (2018).

Carter, G. A. & Knapp, A. K. Leaf optical properties in higher plants: linking spectral characteristics to stress and chlorophyll concentration. Am. J. Bot. 88, 677–684. https://doi.org/10.2307/2657068 (2001).

Rapaport, T., Hochberg, U., Cochavi, A., Karnieli, A. & Rachmilevitch, S. The potential of the spectral ‘water balance index’ (WABI) for crop irrigation scheduling. New Phytol. 216, 741–757. https://doi.org/10.1111/NPH.14718 (2017).

Prudnikova, E. et al. Influence of soil background on spectral reflectance of winter wheat crop canopy. Remote Sens. 11, 1932. https://doi.org/10.3390/RS11161932 (2019).

Li, W. et al. RSARE: a physically-based vegetation index for estimating wheat green LAI to mitigate the impact of leaf chlorophyll content and residue-soil background. ISPRS J. Photogram. Remote Sens. 200, 138–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isprsjprs.2023.05.012 (2023).

Zou, X. & Mõttus, M. Sensitivity of common vegetation indices to the canopy structure of field crops. Remote Sens. (Basel). 9, 253. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs9100994 (2017).

Nanda, M. K., Giri, U. & Bera, N. Canopy temperature-based water stress indices: potential and limitations. In Advances in Crop Environment Interaction 365–385 (Springer, 2018).

Colaizzi, P., Evett, S., O’shaughnessy, S. A. & Howell, T. A. Using Plant Canopy Temperature to Improve Irrigated Crop Management (Springer, 2012).

Shi, B. et al. Improving water status prediction of winter wheat using multi-source data with machine learning. Eur. J. Agron. 139, 256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eja.2022.126548 (2022).

Zhang, X. et al. Improving the prediction performance of leaf water content by coupling multi-source data with machine learning in rice (Oryza sativa L). Plant. Methods. 20, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1186/S13007-024-01168-5 (2024).

Cervera-Díaz, M., León-Chávez, M. F., Santiesteban-Toca, C. & Lozoya, C. Greenhouse smart irrigation based on soil moisture and vegetation index measurements. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Conference on Technologies for Sustainability, SusTech 2023; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc. 20–24 (2023).

Owino, L., Söffker, D., Nicholas Koumboulis, F. & Kouvakas, N. How much is enough in watering plants? state-of-the-art in irrigation control: advances, challenges, and opportunities with respect to precision irrigation. Front. Control Eng. 3, 982463. https://doi.org/10.3389/FCTEG.2022.982463 (2022).

Tunca, E., Selim Köksal, E., Öztürk, E., Akay, H. & Çetin Taner, S. Accurate estimation of sorghum crop water content under different water stress levels using machine learning and hyperspectral data Emre Tunca · Eyüp Selim Köksal · elif Öztürk · Hasan Akay · Sakine Çetin Taner. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-023-11536-8 (2024).

Zheng, X., Yu, Z., Shi, Y. & Liang, P. Differences in water consumption of wheat varieties are affected by root morphology characteristics and post-anthesis root senescence. Front. Plant. Sci. 12, 256. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2021.814658 (2022).

Navarro, A. et al. Sorting biotic and abiotic stresses on wild rocket by leaf-image hyperspectral data mining with an artificial intelligence model. Plant Methods 18, 45. https://doi.org/10.1186/S13007-022-00880-4 (2022).

Koh, S. S. et al. Classification of plant endogenous States using machine learning-derived agricultural indices. Plant. Phenomics. 5, 256. https://doi.org/10.34133/PLANTPHENOMICS.0060 (2023).

Vásquez, R. A. R., Heenkenda, M. K., Nelson, R. & Segura Serrano, L. Developing a new vegetation index using cyan, orange, and near infrared bands to analyze soybean growth dynamics. Remote Sens. . 15, 2888. https://doi.org/10.3390/RS15112888 (2023).

Sulaiman, P. S., Khalid, F., Azman, A., Kahar, Z. A. & Hanafi, M. Reviewing vegetation indices for mobile application: potentials and challenges. J. Adv. Res. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 35, 33–46. https://doi.org/10.37934/ARASET.35.2.3346 (2024).

Wen, P. et al. Adaptability of wheat to future climate change: effects of sowing date and sowing rate on wheat yield in three wheat production regions in the North China plain. Sci. Total Env. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.165906 (2023).

Rouse, R. W. H., Haas, J. A. W. & Deering, D. W. ’aper A 20 monitoring vegetation systems in the great plains with ERTS (2024).

Gao, B. C. NDWI - a normalized difference water index for remote sensing of vegetation liquid water from space. Remote Sens. Environ. 58, 257–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0034-4257(96)00067-3 (1996).

Rondeaux, G., Steven, M. & Baret, F. Optimization of soil-adjusted vegetation indices. Remote Sens. Environ. 55, 95–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/0034-4257(95)00186-7 (1996).

Zarco-Tejada, P. J., Rueda, C. A. & Ustin, S. L. Water content estimation in vegetation with MODIS reflectance data and model inversion methods. Remote Sens. Environ. 85, 109–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0034-4257(02)00197-9 (2003).

Ceccato, P., Flasse, S., Tarantola, S., Jacquemoud, S. & Grégoire, J. M. Detecting vegetation leaf water content using reflectance in the optical domain. Remote Sens. Environ. 77, 22–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0034-4257(01)00191-2 (2001).

Penuelas, J., Pinol, J., Ogaya, R. & Filella, I. Estimation of plant water concentration by the reflectance water index WI (R900/R970). Int. J. Remote Sens. 18, 2869–2875. https://doi.org/10.1080/014311697217396 (1997).

Peñuelas, J., Gamon, J. A., Fredeen, A. L., Merino, J. & Field, C. B. Reflectance indices associated with physiological changes in nitrogen- and water-limited sunflower leaves. Remote Sens. Environ. 48, 135–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/0034-4257(94)90136-8 (1994).

Sawatsky, M. L., Clyde, M. & Meek, F. Partial least squares regression in the social Sciences. Quant. Methods Psychol. 11, 52 (2015).

Sajjad Abdollahpour, S., Buehler, R., Le, C., Nasri, H. T. K. & Hankey, A. S. Built environment’s nonlinear effects on mode shares around BRT and rail stations. Transport. Res. Part D: Transport Env. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2024.104143 (2024).

Funding

This work was funded by the “Agricultural Science and Technology Major Project”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author Contributions: James E. Kanneh: Conceptualisation, Methodology, Investigation, Software, Formal analysis, Visualisation, Writing—original draft, Writing—Review & editing. Jinglei Wang: Conceptualisation, Methodology, Writing—Review & editing, Supervision, Data curation, Validation, Project administration, Funding acquisition. Caixia Li: Conceptualisation, Methodology, Writing—Review & editing, Supervision, Data curation, Validation, Project administration. Yanchuan Ma: Methodology, Software, Writing—Review & editing, Validation. Shengli Li: Writing—Review & editing, Validation. Daokuan Zhong: Investigation, Writing—Review & editing. Zuji Wang: Investigation, Writing—Review & editing. Djifa Fidele Kpalari: Writing—Review & editing. BE Madjebi Collela: Writing—Review & editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kanneh, J.E., Wang, J., Li, C. et al. Novel indices and multi-source data fusion for monitoring plant moisture stress in winter wheat fields. Sci Rep 16, 3836 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33905-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33905-8