Abstract

Cigarette smoke (CS) is a major risk factor for many respiratory diseases, including lung cancer, contributing to genomic instability, chronic inflammation, and impaired immune responses. Macrophages are among the most affected cell types, and CS-induced polarization has been increasingly associated with tumor promotion and reduced anti-tumor activity. G quadruplexes (G4) are non-canonical structures of RNA and DNA, enriched in G-rich sequences (such as telomeres or gene promoters), influencing several layers of gene expression regulation and DNA stability. More recently, genome-wide approaches have enabled high-resolution mapping of G4 structures in human cells, confirming the formation and functionality of G4 in multiple biological contexts. G4 structures can be bound and stabilized by small molecules such as RHPS4, with a consequent impairment of cell proliferation in cancer cells and downregulation of several pro-oncogenic factors. However, no studies have previously addressed whether CS exposure affects G4 formation or stability. Here, we found that CS exposure destabilizes G4 structure formation in cultured THP-1 monocytes differentiated into macrophages, antagonizing the effect of the G4 ligand RHPS4. In this context, CS exposure strongly induces the activation of IL-1β and TNF-α, both containing a G4 putative forming region in their promoters, suggesting that CS-linked cytokine modulation could involve a G4-dependent mechanism. Moreover, in proliferating THP-1, CS antagonizes the anti-proliferative effect of RHPS4 and has an opposite effect on the expression of G4 containing pro-oncogenic genes (like myc and bcl2). Overall, these findings showed for the first time a relationship between CS exposure and G4 structures, representing a new unexplored regulatory mechanism underlying smoking-related conditions and carcinogenesis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cigarette smoke (CS) is a major risk factor for lung cancer, causing 7.69 million deaths and 200 million disability-adjusted life-years globally in 20191. Despite a well-established epidemiological link, the underlying mechanisms are not completely understood. Notably, immune system imbalance, particularly pro-tumorigenic macrophage activity, has gained increasing attention as a key factor in lung cancer onset and progression2. Several studies have shown the capacity of tumor-associated macrophages to promote lung cancer cell proliferation, metastasis, and immunosuppression3,4. In addition, CS carcinogens, such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), affect both pulmonary innate and adaptive immunity in the lungs, causing the release of cytokines and inflammatory mediators from tumor inflammatory cells, including macrophages5,6,7,8. G-quadruplexes (G4) are non-canonical secondary structures of DNA found in guanine-rich DNA and RNA9. G4 are involved in several processes, such as DNA replication, transcription, RNA stability, and translation. Interestingly, gene promoters are enriched in guanine sequences, which easily undergo G4 structure formation, potentially influencing their expression9. Therefore, the stabilization or disruption of G4 motifs can either promote or inhibit gene expression, particularly of oncogenes, thereby affecting cancer cell growth and survival. Over the last two decades, extensive computational and experimental studies have revealed widespread potential and experimentally validated G4 structures across the human genome. Early analyses demonstrated that guanine-rich putative G4-forming sequences (PQS) are prevalent and non-randomly distributed in the genome, particularly enriched in promoters including many oncogenes10,11,12. More recently, genome-wide approaches such as G4-seq and G4 ChIP-seq have enabled high-resolution mapping of G4 structures in human cells, confirming the formation and functionality of G4 in multiple biological contexts13,14. Telomeres are nucleoprotein complexes that protect chromosome extremities, and their dysfunction can result in cell aging and genomic instability, which are considered hallmarks of numerous tumors, including lung cancer15. Telomeric DNA is constituted by double-stranded tandem repeats of the hexamer TTAGGG, which terminates with a protruding G-rich single strand. Telomeres are perfect substrates for G4 formation, both on the G-rich strand of DNA (especially during telomere replication or transcription, when the double helix is denatured) and on the protruding G-rich extremity called the G-overhang16. Consequently, at telomeres, G4 stabilization affects replication and induces the delocalization of telomeric shelterin factors, such as TRF2 and POT1, activating a DNA damage response pathway and eventually apoptosis17,18. Telomeres are prone to guanine oxidation, which can trigger the loss of telomeric DNA tracts and the activation of the DNA damage response pathway19. It is well known that the DNA damage response at telomeres can drive the establishment of an inflammatory phenotype in immune cells. Moreover, CS is known to change the telomere length in immune cells, such as macrophages, by affecting their activation, polarization, and immune responses, all associated with immune senescence, chronic inflammatory diseases, and less efficient immune surveillance against tumor microenvironment. Overall, G4 structures are potential targets in cancer therapy because of their involvement in oncogene expression, cellular replication, genomic stability, and immune system dysregulation. Several small molecules targeting G4 have been developed as potential anti-cancer therapeutics. Currently, one of the most effective and well-studied G4 ligands is RHPS4 (pentacyclic acridine, 3,11-difluoro-6,8,13-trimethyl-8Hquino [4,3,2-kl] acridinium methosulfate). It is characterized by a very high specificity for telomeric G417,20,21 and displays G4 stabilizing properties leading to in vitro and in vivo cytotoxicity in a wide panel of tumor cells. Based on the known involvement of both CS and G4 structures in lung cancer pathogenesis, and taking in account that small molecules targeting G4 could influence macrophage activity and general immunity, here we investigated here for the first time, the CS effects on G4 stability in an in vitro macrophage model, and the resulting effect on telomere dysfunction, DNA damage activation and gene expression through RHPS4 as a pharmacological tool.

Materials and methods

Preparation of CS extract

CS extract (CSE) was prepared bubbling ten Red Marlboro cigarettes (Phillip Morris; Cracow, Poland) without a filter through 250 ml of serum-free RPMI with a customized vacuum pump apparatus. The obtained suspension was adjusted to pH 7.4, filtered through a 0.20 μm pore to remove bacteria and large particles and stored at − 80 °C. In the CSE treatments, the cells were maintained in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% CSE, based on our previously published data22.

Cell culture and treatments

THP-1 cells (ATCCR TIB-202TM) which represent the most recognized in vitro model23, were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, Virginia, USA). The cells were grown in 75 cm2 tissue culture flasks and maintained at 2 × 105 cells/ml in RPMI-1640 medium containing 10% FBS, 2 mM L-glutamine, 200 U/ml penicillin, and 200 mg/ml streptomycin at 37 °C 5% CO2/95% humidified air. To obtain a macrophage-like phenotype, THP-1 cells were treated with 100 ng/ml phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA, Sigma-Aldrich) for two days to induce the typical hallmarks of macrophages and adhere to the plate prior to any additional treatment. The cells were then incubated with fresh medium for one day to allow cell recovery and exposed to the CSE or RHPS4 conditioned media.

Immunofluorescence and IF/FISH

At the end of treatments, cells were fixed in 2% formaldehyde, permeabilized in 0.25% Triton X-100 in PBS for 5 min at room temperature and blocked in 5% BSA for 1 h. Then, samples were processed for immunolabeling with BG4 antibody (1:500) (Absolute Antibody), followed by the anti-mouse IgG Alexa fluor 488 secondary antibody (1:1000) (Cell Signaling). Due to the nature of the BG4 antibody (a single-chain antibody), no isotype control is possible (Quantification was performed using Fiji software. Nuclei were segmented via DAPI signal, and BG4-positive foci were counted using automated spot detection. A background ROI was selected in a signal-free region to calculate the mean background intensity and its standard deviation (SD) and a minimum intensity threshold of mean background + 2 standard deviation was applied to define BG4-positive foci. At least 100 cells per condition were analyzed in three independent experiments. For IF/FISH staining, samples were re-fixed in 2% formaldehyde, dehydrated with ethanol series (70, 90, 100%), air dried, co-denatured for 3 min at 80 °C with a Cy3-labeled PNA probe, specific for telomere sequences (TelC-Cy3, Panagene, Daejon, South Korea), and incubated for 2 h in a humidified chamber at room temperature in the dark. After hybridization, slides were washed with 70% formamide, 10 mM TrisHCl pH 7.2, BSA 0.1%, and then rinsed in TBS/Tween 0.08%, dehydrated with ethanol series, and finally counterstained with DAPI (0.5 µg/ml, Sigma-Aldrich) and mounted on slides in mounting medium (Gelvatol Moviol, Sigma Aldrich). Fluorescence signals were acquired with a CrestOptics V3 confocal spinning disk mounted on a Nikon Ti2-E Inverted microscope with an integrated camera and a laser source (Lumencor). Colocalization presence was assessed by using the Matcol software24.

RT-PCR analysis

One million/well THP-1 cells were cultured and differentiated in 6-well plates and then treated with CSE for 24 h in presence or absence of 1µ RHPS4 for 24 h. Total RNA was obtained using Trizol reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and subjected to reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction using the high-capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RT-PCR was performed using TaqMan™ Universal PCR Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and TaqMan Gene Expression assays (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol on a QuantumStudio3™ Real-Time PCR System. GAPDH was used as a housekeeping gene to normalize mRNA expression. Data from all RT–PCR experiments were analyzed by normalizing to the endogenous control applying the comparative 2ˆ−ΔΔCt method, where ΔCt = CtmRNA – Ct housekeeping mRNA, whereas the relative quantification of differences in expression was conducted with ΔΔCt = ΔCtTREATMENT − ΔCtCTR.

Cell growth curve

THP-1 cells were seeded at a density of 105 cells/well in 24 multiwell plates. After 24 h the cells were treated with 10% CSE, 1µM RHPS4 or both consecutively. Control samples were treated with DMSO. Cell growth was monitored every two days, by counting the number of viable cells: 50 µl of cell suspension was mixed with Trypan blue staining solution, and the number of negative cells was scored manually in the Burker chamber.

DNA extraction and relative quantification of oxidized bases by quantitative PCR

Genomic DNA (gDNA) was extracted from cultured cells using the NucleoSpin DNA RapidLyse Kit (Macherey-Nagel) following the manufacturer’s instructions. To quantify the relative accumulation of oxidative bases at telomeric loci, the procedure described in13 was performed. Briefly, for each condition 400 ng of gDNA was incubated with 12 units of FPG (New England BioLabs) in 1× NEB buffer at 37 °C overnight. The quantitative real-time amplification (qPCR) was performed on 40 ng of digested or undigested gDNA in a 1xSYBR Green master mix (Applied Biosystems [AB]), including specific telomeric or 36B4 primers (see below). Following qPCR amplification, profiles of FPG-treated and FPG-untreated samples were compared by calculating the relative ΔCT (CT digested – CT undigested).

Primers:

36B4-FW CAGCAAGTGGGAAGGTGTAATCC.

36B4-RVCCCATTCTATCATCAACGGGTACAA.

Telo-8oxoG FW CGGTTTGTTTGGGTTTGGGTTTGGGTTTGGGTTTGGGTT.

Telo-8oxoG RV GGCTTGCCTTACCCTTACCCTTACCCTTACCCTTACCCT.

PQS analysis in-silico

TNFα (TNFA LOC100287329/NR_149045.1) and IL-1β (IL1B/NM_000576.3/NP_000567.1) promoter regions (up to 1200–1500 bp upstream the ATG) were analyzed by the QGRS mapper (https://bioinformatics.ramapo.edu/QGRS/analyze.php)10,11,12 with the default parameters: Max length: 30; Min G group: 2; Loop size: 0 to 36. The results were exported as excel tables with the calculated G-Score. The same sequences were analyzed by G4 hunter tool (https://bioinformatics.ibp.cz/#/analyse/quadruplex) with default parameters: threshold 1.2.

Guanine oxidation by CSE in test-tube conditions

The stability of guanosine was evaluated in a 10% RPMI CSE aqueous solution. A 100 µM guanosine solution in water was first analyzed by HPLC (Shimadzu Prominence system) using a C18 reversed-phase column (Phenomenex Kinetex, 4.6 × 150 mm, 5 μm) and a linear gradient from 0 to 40% acetonitrile in water (0.1% TFA) over 10 min at a flow rate of 0.6 mL/min to obtain the reference chromatographic profile. Subsequently, 100 µL of a 1 mM guanosine stock solution were added to 900 µL of 10% RPMI CSE and the mixture was incubated at 37 °C. Aliquots (20 µL) were collected at 0 and 24 h and analyzed under identical HPLC conditions. Figure 7A shows representative images.

Results

CS induces G4-structure destabilization

To monitor the effect of CS on nuclear G4 structures, macrophages obtained from PMA- differentiated-THP-1 were treated with 10% CSE, 100nM or 1µM RHPS4 for 24 h. Subsequently, standard immunofluorescence analysis was performed using a specific BG4 antibody. BG4-positive foci were detected and quantified using an automated spot analysis pipeline in Fiji. As BG4 can only bind stable structures, the antibody signals correspond to the presence or absence of stable G4 structures. Therefore, the percentage of cells expressing the BG4 signal was determined. CSE induced a significant decrease in BG4 positive cells compared to the control suggesting that CS could have G4 destabilization-properties (Fig. 1A). Treatment with 1µM RHPS4, which is a G4 stabilizer, showed a significantly higher percentage of cells expressing the BG4 signal than the control group, whereas 100nM RHPS4 had no effect (Fig. 1A).

CSE reduces BG4 staining. Macrophages derived from THP-1differentiated with PMA were incubated with CSE, RHPS4 100nM or 1µM for 24 h. Successively, cells were processed for immunofluorescence with an anti-BG4 antibody followed by a TRITC-conjugated secondary antibody, counterstained with DAPI and analyzed at fluorescence microscope. (A). Representative immunofluorescence merged images showing BG4 foci (pink), and nuclear DNA labeled with DAPI (blue) in the indicated samples (B): BG4-positive foci were quantified in Fiji: nuclei were segmented via DAPI, background intensity was measured in a signal-free ROI, and the detection threshold was set at mean background + 2 SD to discriminate true BG4 spots. Histograms represent the percentage of cells expressing BG4 signal. Microscopy was performed using 60X objectives and analyzed by Fiji software. Statistical analysis: one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. **=P < 0.01; ****=P < 0.0001.

Since G4 structures are enriched at telomeric regions, we further evaluated the effect of CSE on G4 stability at telomeric DNA by co-staining the samples with the anti-G4 antibody and a fluorescent telomeric probe and quantifying the number of colocalizations between the two signals (representative images are shown in Fig. 2A). By quantifying the number of telo/G4 colocalizing spots, we observed that 1 µM RHPS4 significantly increased both the total G4 spots and the telo/G4 colocalizing spots per nucleus (Fig. 2B). Coherently, also the average number of colocalizations per nucleus was increased by the RHPS4 treatment (Fig. 2C). More interestingly, the combination of CSE and RHPS4 led to a significant reduction in BG4 signal at genomic level (Fig. 2B) and to a significant reduction of the average number of tel/G4 spots (Fig. 2C), compared to the treatment with RHPS4 alone (Fig. 2A-C).

CSE counteracts G4 stabilization by RHPS4. Macrophages derived from THP-1differentiated with PMA were incubated for 24 h with CSE10%, in the presence of 1 µM RHPS4, or with 1 µM RHPS4 alone. DMSO was administered in control samples. After treatment, cells were processed for IF/FISH staining with anti-BG4 and Cy3-(TTAGGG)n PNA probe, and counterstained with DAPI. Representative images are shown in (A) at 60X magnification. Bar = 10 μm. (B)The histograms report the percentage of cells positive for anti-BG4 spots (Total BG4, grey bars) or positive for the presence of colocalization foci between anti-BG4 and Cy3-(TTAGGG)n spots in the indicated samples. (Tel-BG4, white bars). The mean of three independent experiments is shown. Bars are SD. Statistically significant differences were calculated with the one-way Anova test. *=P < 0.05; ***=P < 0.001; ****=P < 0.0001. (C) The graph reports the average number of Tel-BG4 colocalizations. Statistically significant differences were calculated with the Kruskal-Wallis test. *=P < 0.05; ***=P < 0.001; ****=P < 0.0001.

CS induces genomic and telomeric DNA damage

DNA damage is one of the main causes of oncogenic transformation of cells. Single and double DNA strand breaks can be monitored by measuring Ser 139 phosphorylation on histone H2AX (defined as γH2AX). The presence of γH2AX, labels unprotected and dysfunctional telomeres, which lead to genomic instability and accompany cancer progression. Therefore, we evaluated the induction of DNA damage at the genomic level and at dysfunctional telomeres by assessing the percentage of γH2AX-positive or TIFs (namely Telomere’s dysfunction Induced Foci, identified by the colocalizations between γH2AX and a telomeric probe) positive cells respectively, after exposure to CSE and/or G4 stabilization (Fig. 3B). Moreover, to evaluate the extent of telomeric damage at the single-cell level, we evaluated the average number of TIFs/nucleus (Fig. 3C). As shown in Fig. 3, exposure to CSE 10%, RHPS4 or both caused strand breaks at genomic and telomeric DNA, confirming CSE and RHPS4-induced genomic toxicity. Interestingly, exposure to combined treatment did not increase the percentage of damaged cells, nor the number of TIFs/nucleus (Fig. 3).

CSE and RHPS4 induce DDR in non-additive manner Macrophages derived from THP-1differentiated with PMA were treated as above described and processed for IF/FISH staining with anti-γH2AX antibody and Cy3-TTAGGG PNA probe, and counterstained with DAPI. Representative images are shown in (A) at 60X magnification. Bar = 10 μm (B) The histograms report the percentage of cells displaying γH2AX foci or TIFs (γH2AX- Cy3-TTAGGG colocalization foci) in the indicated samples. The mean of three independent experiments is shown. Bars are SD. Statistically significant differences were calculated with the two-way Anova test. *=P < 0.05; ***=P < 0.001; ****=P < 0.0001. (C) The graph reports the average number of TIFs. Statistically significant differences were calculated with the Kruskal-Wallis test. ***=P < 0.001; ****=P < 0.0001.

CS impairs G4 stabilization with an antagonistic effect on cell proliferation and oncogene expression

As a consequence of replication-dependent DNA damage, cell proliferation is generally affected by G4 stabilization. Growing THP-1 cells exposed to CSE and/or RHPS4 displayed a reduction in the growth rate (Fig. 4A). RHPS4 reduces cell survival in a time dependent manner, as already described, reaching the highest effect at 8 h. Conversely, CSE treatment initially slightly increases cell growth (Fig. 4A and B, day 4), while at the final endpoint it results in a decrease in the percentage of cell survival (Fig. 4A and B, day 8). Interestingly, the combined effect of CSE and RHPS4 results in antagonistic effect. In lung cancer, the transcription levels of different genes are frequently dysregulated and contribute to malignancy by regulating cancer cell growth and survival, activating cycle-promoting proteins, antiapoptotic protein levels, and cellular metabolism. Among these, c-MYC and BCL2 were the most significant containing G-rich regions that could adopt intramolecular G4 conformations. These G4 structures can act as transcriptional modulation elements and G4-interact molecules have been shown to regulate gene expression25,26. Therefore, to investigate the effect of CSE on these genes and their potential link to G4, we assessed their mRNA expression levels in cells exposed to CSE in the presence or absence of RHPS4. Consistent with its G4-destabilizing effect on, CSE induced a significant increase in c-MYC (Fig. 4C) and BCL2 (Fig. 4D) expression levels compared with the control group (p < 0.0001, respectively). Notably, the addition of 1µM RHPS4 showed a great reduction of MYC and BCL2 expression levels, confirming the antagonistic effects of CSE and RHPS4 on proliferative genes, which agrees with the effect on cell proliferation (p < 0.0001 and p < 0.0001, respectively) (Fig. 4C D).

CSE and RHPS4 effect on cell proliferation. Proliferating THP1 were exposed to the indicated treatments. The number of viable cells was monitored every two days and reported in the curves (A). The percentage of surviving cells at each endpoint in treated vs. DMSO samples was reported in the histograms (B). The mean of three independent experiments is shown. Bars are SD. Analysis of c-MYC (C) and BCL2 (D) mRNA expression levels in proliferating THP1 treated as indicated. All samples were run in triplicate, and results are shown as means ± SD. Statistical significance of differences was calculated by Ordinary one-way Anova. **= P < 0.01; ***=P < 0.001; ****=P < 0.0001.

CS induces guanine oxidation at telomeric and genomic sites and upregulates cytokine expression through a G4-dependent mechanism

Some authors have reported that the oxidation of guanine prevents the formation of Hoogsteen hydrogen bonds, which obstructs G4 formation and stability. Therefore, to investigate the molecular basis of the antagonistic effects between CSE and G4 stabilization, we measured the level of guanine oxidation, a common biomarker of oxidative stress, in both genomic and telomeric DNA of THP-1 exposed to CSE, by the 8-OXOG assay. Interestingly, exposure to CSE 10% significantly increased increases the level of guanine oxidation at both genomic and telomeric sites compared to untreated cells (p < 0.05 and p < 0.001, respectively), suggesting that guanine oxidation may directly contribute to CSE-induced destabilization of G4 structures, providing a mechanistic link between environmental stress and altered G4 dynamics (Fig. 5). Notably, the more pronounced increase in guanine oxidation at telomeric regions compared to genomic DNA could suggest that telomeric G4s may be particularly susceptible to CSE-induced oxidative stress, highlighting a potential mechanism by which CSE could preferentially destabilize telomeric G4s, with implications for telomere maintenance, genome stability, and overall cellular function (Fig. 5).

CSE induces guanine oxidation. Macrophages derived from THP-1differentiated with PMA were treated as indicated for 48 h. Then cells were collected, and genomic DNA was extracted and digested with FPG enzyme. Finally, real-time qPCR was performed with specific primers for the indicated regions of interest. Histograms report the fold increase in oxidized guanine levels (8-oxoGua) calculated with the ΔCt method (Ct FPG-digested—Ct undigested). Bars show the mean ± SD from three independent experiments. Statistical significance of differences was calculated by Ordinary one-way Anova. *= P < 0.005; ***=P < 0.001.

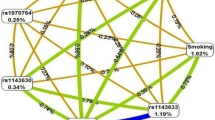

Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) contribute to the onset of a cancer-prone microenvironment by secreting pro-inflammatory factors that regulate proliferation, metastasis, angiogenesis, immunosuppression, and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT)27,28. For instance, TAMs-derived IFN-γ activates JAK/STAT3 and PI3K/AKT signaling pathways ultimately leading to increased Programmed Death- Ligand 1 (PD-L1) in lung cancer29,30. Moreover, macrophages are an important source of IL-1β and TNF-α which are driving cytokines of multiple pulmonary conditions, including cancer. The in-silico study of the regulatory sequences in IL-1β and TNF-α promoters, performed by the QGRS analysis software, showed the presence of putative quadruplex-forming regions in both promoters (Fig. 6A and B) confirmed by the G4hunter search (Supplementary Fig. 1A and B). Based on these results, we analyzed the ability of CSE to modulate the mRNA expression of both genes, finding that IL-1β and TNF-α mRNA was strongly increased by CSE exposure (p < 0.0001, respectively) (Fig. 6C and D). However, the addition of 1µM RHPS4 showed a great reduction in IL-1β and TNF-α expression levels (p < 0.0001, respectively) (Fig. 6C and D), suggesting that the upregulation of these cytokines by CSE could involve a G4-dependent mechanism.

CSE upregulates pro-inflammatory cytokines putatively through G4 destabilization. Identification of G4 putative forming sequences in the promoter regions of IL-1β (A) and TNF-α (B) with the QRGS analysis software. Analysis of IL-1β (C) and TNF-α (D) mRNA expression levels in, macrophages derived from THP-1 differentiated with PMA untreated, treated with CSE for 24 h, or with 1 µM RHPS4 for 24 h following 24 h of CSE exposure. All samples were run in triplicate, and results are shown as means ± SD. Statistical significance was calculated by Ordinary one-way Anova one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. ****=P < 0.0001.

Absence of direct guanine oxidation by CSE in test-tube conditions

Guanosine at 100 µM concentration was incubated with 10% CSE at 37 °C to directly assess whether the aqueous extract components could oxidize guanosine in the absence of cellular metabolism. HPLC-MS/MS analysis (Fig. 7) revealed no detectable formation of 8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanosine, indicating that CSE alone does not chemically induce guanine oxidation under these conditions. This result contrasts with our cellular data, where macrophage exposure to CSE produced robust accumulation of 8-oxoG in genomic and telomeric DNA, suggesting that oxidation requires a metabolically active environment.

Discussion

CS is a major risk factor for many respiratory diseases, including lung cancer. CS is a complex mixture containing over 4800 different compounds, including polycyclic aromatic carcinogens, tobacco-specific nitrosamines, catechols, aldehydes, and other constituents, which can lead to DNA damage directly or indirectly. Indeed, many of these molecules are reactive chemical carcinogens capable of directly binding DNA and inducing mutagenic lesions, while others promote oxidative stress and chronic inflammation, amplifying tumor-promoting processes31. In the lungs of smokers, CS causes inflammatory cascade activation and reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, which results in the accumulation of inflammatory cells32,33. Therefore, CS contributes to lung cancer development, impacting both cancer cell transformation and the tumor microenvironment. On one side, oxidative stress induced by CS alters DNA stability, contributing to the accumulation of prooncogenic mutations in pulmonary epithelial cells. Contemporarily, chronic inflammation contributes to the establishment of a tumor-prone microenvironment. Tumors consist not only of malignant cells but also of host-derived cells recruited from circulation. Among these, TAMs are the most abundant and support tumor progression by secreting pro-inflammatory factors that regulate proliferation, metastasis, angiogenesis, immunosuppression, and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT)22,30. G4 structures are non-canonical structures of nucleic acids forming at G-rich single stranded DNA or RNA, enriched at regulatory regions of the genome (promoters, introns, origins of replication, pericentromeres, and telomeres). Their presence imposes topological stress at G-rich sites during replication and transcription; therefore, specific helicases able to resolve G4 are required to complete those fundamental processes9. On the other hand, stabilization of these structures by specific ligands affects gene expression and DNA stability with opposite mechanisms34,35. Here, we demonstrate for the first time the role of CS in the destabilization of G4 structures in an in-vitro model of AMs. We found that CSE exposure can reduce the presence or stability of G4 structures in macrophages, with an opposite effect compared to RHPS4, a well-known G4 ligand. Moreover, pre-treatment of cells with CSE can also reduce the stabilizing properties of RHPS4 This surprising antagonism between CSE and RHPS4 is observable in both genomic and telomeric sites (these last being considered as preferred sites for RHPS4 binding), and reflected in the effects on DNA damage response, proliferation, and gene expression. Despite its destabilizing effect on G4, CSE can induce DNA damage at both the genomic and telomeric levels. Accordingly, a well-established link has been reported between CS exposure and DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) which represent the most lethal forms of DNA damage36,37,38. Indeed, genotoxins, including benzo(a)pyrene, nitrosamines, aldehydes and oxidants, released by tobacco combustion can induce various forms of DNA adducts which accumulate at multiple genetic loci leading to apoptosis, cell senescence, pro-inflammatory responses, epigenetic modifications and oncogenesis39,40,41,42,43. Nevertheless, we could not detect any additive or synergistic effects between CSE and RHPS4 on DNA damage induction in macrophages, nor on proliferation and survival in growing cells. A possible explanation for this apparent discrepancy resides in the mechanistic insights obtained through the 8-Oxo Guanine assay. The core of the G4 structure is the G-tetrad which consists of four G-rich chains with Hoogsteen hydrogen bonding, ensuring structural stability. Some authors have reported that guanine in G4 structures are highly susceptible to one-electron oxidation by CO3 ions which prevents the formation of Hoogsteen hydrogen bonds, triggering the dissociation of G46,44. Our data showed that CSE can promote guanine oxidation at both genomic and telomeric sites, contemporarily inducing oxidation-dependent DNA damage and destabilization of G4 structures due to a reduced capacity of oxidized guanines to form stable G tetrads. The observation of an increased levels of oxidized guanine after CSE exposure is in line with Deslee et al., who found a significant oxidation of nucleic acids localized to alveolar lung fibroblasts caused by CS-dependent ROS production45. As shown by our cell-free assessment of CSE-induced guanine oxidation, significant oxidative modification does not seem to occur in the absence of a metabolically active environment. Consequently, the destabilization of G-quadruplex DNA observed in cells is likely driven by indirect, cell-dependent oxidative processes rather than by any direct chemical effect of CSE on guanine46,47,48. The effect of G4 stabilization on gene promoter activity has been reported in several genes and experimental systems. G4 presence and stabilization represent an obstacle to transcription factor binding, consequently leading to an impairment of transcription initiation. Therefore, G4 destabilization is expected to result in upregulation of mRNA levels of G4-containing genes. In agreement with this, c-myc and bcl-2 mRNA were upregulated by CSE exposure, despite the inhibitory effect of CSE on proliferation. Consequently, CSE exposure induces a transient positive effect on cell growth, which is reversed by the accumulation of oxidative DNA damage, and eventually leads to an overall inhibition of cell survival, unveiling a complex network of pathways with opposite functional effects. IL-1β and TNFα are important cytokines participating in the pathogenesis of multiple pulmonary conditions including lung cancer44,45. AMs are a key source of these cytokines, especially following CS stimulation49,50. In recent years, different mechanisms underlying the effects of CS on cytokine secretion have been investigated. For instance, Zhang et al. reported that in patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), CS can induce pyroptosis through the NLRP3 inflammasome and caspase-1 cleavage, resulting in downstream molecule activation and an increase in IL-1β and IL-18 production7. In addition, Xu et al. suggested that CS can amplify LPS-induced macrophage secretion of IL-1β and TNFα through substance P release, which activates nuclear factor-κB via neurokinin 1 receptor (NK1R) binding28. However, CS can affect cytokine production through intricate and multiple downstream pathways. G4s has been proven to be involved not only in DNA replication, transcription and stability but also in the regulation of genes related to inflammation-derived disorders51,52,53. Previous investigations have identified G-rich sequences within the promoter regions of many cytokine-finding genes, including IL-6, IL-12, IL-17, TNFα and IL-1β54,55. Our in-silico study of the regulatory sequences in IL-1β and TNF-α promoters, showed the presence of putative quadruplex-forming regions. As expected, CSE was able to positively modulate the mRNA expression of both genes. Conversely, after stabilizing with RHPS4, we found an opposite trend in the mRNA levels of these cytokines. Even in the absence of deeper molecular investigation assessing a direct link between stabilization of the putative G4 forming region, and promoter activity, the data collected so far strongly suggests that CSE-linked cytokine modulation could involve a G4-dependent mechanism. It is important to note that our data are based on THP-1 derived macrophages, a widely used yet simplified in vitro model reflecting key features of human macrophage responses. Therefore, additional validation in primary macrophages, co-culture systems with lung cancer cells or in vivo models will be necessary to fully define the impact of CS on G4 stability within the lung microenvironment. Overall, our findings showed for the first time a relationship between CSE exposure and G4 structures, highlighting that G4 modulation could be implicated in CS-mediated effects on AMs properties. This evidence could allow future studies focused on a better understanding of the regulatory mechanisms underlying smoking-related conditions and carcinogenesis and provide a new and intriguing path for the pharmacological treatment of lung cancer.

Data availability

Data presented in the study are included in the article. Data are available upon request, and further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

References

Reitsma, M. B. et al. Spatial, temporal, and demographic patterns in prevalence of smoking tobacco use and attributable disease burden in 204 countries and territories, 1990â€2019: a systematic analysis from the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet 397, 2337–2360 (2021).

Kloosterman, D. J. & Akkari, L. Macrophages at the interface of the co-evolving cancer ecosystem. Cell 186, 1627–1651 (2023).

Liao, L. et al. The role and clinical significance of tumor-associated macrophages in the epithelial–mesenchymal transition of lung cancer. Front. Oncol. 15, (2025).

Sedighzadeh, S. S., Khoshbin, A. P., Razi, S. & Keshavarz-Fathi, M. Rezaei, N. A narrative review of tumor-associated macrophages in lung cancer: regulation of macrophage polarization and therapeutic implications. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 10, 1889–1916 (2021).

Cyprus, G. N., Overlin, J. W., Hotchkiss, K. M., Kandalam, S. & Olivares-Navarrete, R. Cigarette smoke increases pro-inflammatory markers and inhibits osteogenic differentiation in experimental exposure model. Acta Biomater. 76, 308–318 (2018).

Deslee, G. et al. Cigarette smoke induces nucleic-acid oxidation in lung fibroblasts. Am. J. Respir Cell. Mol. Biol. 43, 576–584 (2010).

Zhang, M. Y. et al. Cigarette smoke extract induces pyroptosis in human bronchial epithelial cells through the ROS/NLRP3/caspase-1 pathway. Life Sci. 269, 119090 (2021).

da Silva, C. O. et al. Alteration of immunophenotype of human macrophages and monocytes after exposure to cigarette smoke. Sci. Rep. 10, 1–13 (2020).

Varshney, D., Spiegel, J., Zyner, K., Tannahill, D. & Balasubramanian, S. The regulation and functions of DNA and RNA G-quadruplexes. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 459–474 (2020).

Huppert, J. L. & Balasubramanian, S. Prevalence of quadruplexes in the human genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, 2908–2916 (2005).

Huppert, J. L. & Balasubramanian, S. G-quadruplexes in promoters throughout the human genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, 406–413 (2007).

Chen, L., Dickerhoff, J., Sakai, S. & Yang, D. DNA G-Quadruplex in human telomeres and oncogene promoters: Structures, Functions, and small molecule targeting. Acc. Chem. Res. 55, 2628–2646 (2022).

Chambers, V. S. et al. High-throughput sequencing of DNA G-quadruplex structures in the human genome. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 877–881 (2015).

Hänsel-Hertsch, R. et al. G-quadruplex structures mark human regulatory chromatin. Nat. Genet. 48, 1267–1272 (2016).

Borges, G., Criqui, M. & Harrington, L. Tieing together loose ends: telomere instability in cancer and aging. Mol. Oncol. 16, 3380–3396 (2022).

Bryan, T. M. G-quadruplexes at telomeres: Friend or foe? Molecules 25, (2020).

Salvati, E. et al. Telomere damage induced by the G-quadruplex ligand RHPS4 has an antitumor effect. J. Clin. Investig. 117, (2007).

Di Maro, S. et al. Shading the TRF2 recruiting function: A new horizon in drug development. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, (2014).

Singh, A., Kukreti, R., Saso, L. & Kukreti, S. Oxidative stress: role and response of short guanine tracts at genomic locations. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20 (17), 4258 (2019).

Salvati, E. et al. A basal level of DNA damage and telomere deprotection increases the sensitivity of cancer cells to G-quadruplex interactive compounds. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, (2015).

Leonetti, C. et al. G-quadruplex ligand RHPS4 potentiates the antitumor activity of camptothecins in preclinical models of solid tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 14, (2008).

Mirra, D. et al. MiRNA signatures in alveolar macrophages related to cigarette smoke: assessment and bioinformatics analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 26, (2025).

Siddiqui-Jain, A., Grand, C. L., Bearss, D. J. & Hurley, L. H. Direct evidence for a G-quadruplex in a promoter region and its targeting with a small molecule to repress c-MYC transcription. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 99, 11593–11598 (2002).

Kumar, S. et al. Contrasting roles for G-quadruplexes in regulating human Bcl-2 and virus homologues KSHV KS-Bcl-2 and EBV BHRF1. Sci. Rep. 12 (1), 12–5019 (2022). (2022).

Chen, Y., Tan, W. & Wang, C. Tumor-associated macrophage-derived cytokines enhance cancer stem-like characteristics through epithelial–mesenchymal transition. Onco Targets Ther. 11, 3817–3826 (2018).

Xu, J., Xu, F. & Lin, Y. Cigarette smoke synergizes lipopolysaccharide-induced interleukin-1β and tumor necrosis factor-α secretion from macrophages via substance P-mediated nuclear factor-κB activation. Am. J. Respir Cell. Mol. Biol. 44, 302–308 (2011).

Polverino, F. et al. Similar programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression profile in patients with mild COPD and lung cancer. Sci. Rep. 12, (2022).

Zhang, X. et al. PD-L1 induced by IFN-γ from tumor-associated macrophages via the JAK/STAT3 and PI3K/AKT signaling pathways promoted progression of lung cancer. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 22, 1026–1033 (2017).

Vadhanam, M. V., Thaiparambil, J., Gairola, C. G. & Gupta, R. C. Oxidative DNA adducts detected in vitro from redox activity of cigarette smoke constituents. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 25, 2499–2504 (2012).

Genin, M., Clement, F., Fattaccioli, A., Raes, M. & Michiels, C. M1 and M2 macrophages derived from THP-1 cells differentially modulate the response of cancer cells to Etoposide. BMC Cancer. 15, 1–14 (2015).

Ito, K. et al. Cigarette smoking reduces histone deacetylase 2 expression, enhances cytokine expression, and inhibits glucocorticoid actions in alveolar macrophages. FASEB J. (2001).

Ciccia, A. & Elledge, S. J. The DNA damage response: making it safe to play with knives. Mol. Cell. 40, 179–204 (2010).

Mah, L. J., El-Osta, A. & Karagiannis, T. C. γH2AX: a sensitive molecular marker of DNA damage and repair. Leukemia 24:4 24, 679–686 (2010).

Mohanty, S. K., Chiaromonte, F. & Makova, K. D. Evolutionary dynamics of G-quadruplexes in human and other great ape telomere-to-telomere genomes. bioRxiv (2024).

Luo, Y. et al. Guidelines for G-quadruplexes: I. In vitro characterization. Biochimie 214 (Pt A), 5–23 (2023).

Bekker-Jensen, S. & Mailand, N. Assembly and function of DNA double-strand break repair foci in mammalian cells. DNA Repair. (Amst). 9, 1219–1228 (2010).

Aoshiba, K., Zhou, F., Tsuji, T. & Nagai, A. DNA damage as a molecular link in the pathogenesis of COPD in smokers. Eur. Respir. J. 39, 1368–1376 (2012).

Hecht, S. S. Progress and challenges in selected areas of tobacco carcinogenesis. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 21, 160–171 (2008).

Mirra, D. et al. Lung microRNAs expression in lung cancer and COPD: A preliminary study. Biomedicines 11, (2023).

Mirra, D. et al. MicroRNA monitoring in human alveolar macrophages from patients with Smoking-Related lung diseases: A preliminary study. Biomedicines 12, 1050 (2024).

Esposito, R. et al. The role of MMPs in the era of CFTR modulators: an additional target for cystic fibrosis patients? Biomolecules 13, 350 (2023).

Singh, A., Kukreti, R., Saso, L. & Kukreti, S. Oxidative stress: role and response of short guanine tracts at genomic locations. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, (2019).

Wu, S. et al. Crosstalk between G-quadruplex and ROS. Cell. Death Dis. 14, 1–16 (2023).

Barnes, P. J. The cytokine network in asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J. Clin. Invest. 118, 3546–3556 (2008).

Churg, A., Zhou, S., Wang, X., Wang, R. & Wright, J. L. The role of Interleukin-1β in murine cigarette smoke–induced emphysema and small airway remodeling. 40, 482–490 (2012).

Chang, K. H. et al. NADPH oxidase (NOX) 1 mediates cigarette smoke-induced superoxide generation in rat vascular smooth muscle cells. Toxicol. Vitro. 38, 49–58 (2017).

Li, N. et al. The role of oxidative stress in ambient particulate matter-induced lung diseases and its implications in the toxicity of engineered nanoparticles. Free Radic Biol. Med. 44, 1689–1699 (2008).

Hahm, J. Y. et al. 8-Oxoguanine: from oxidative damage to epigenetic and epitranscriptional modification. Exp. Mol. Med. 54, 1626–1642 (2022).

Thorley, A. J. et al. Differential regulation of cytokine release and leukocyte migration by lipopolysaccharide-stimulated primary human lung alveolar type II epithelial cells and macrophages. J. Immunol. 178, 463–473 (2007).

Drannik, A. G. et al. Impact of cigarette smoke on clearance and inflammation after Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med. 170, 1164–1171 (2004).

Guo, J. U. & Bartel, D. P. RNA G-quadruplexes are globally unfolded in eukaryotic cells and depleted in bacteria. Science 353, (2016).

Gosai, S. J. et al. Global analysis of the RNA-protein interaction and RNA secondary structure landscapes of the Arabidopsis nucleus. Mol. Cell. 57, 376–388 (2015).

Esnault, C. et al. G-quadruplexes are promoter elements controlling nucleosome exclusion and RNA polymerase II pausing. Nat. Genet. 57, (2025).

Bidula, S. Analysis of putative G-quadruplex forming sequences in inflammatory mediators and their potential as targets for treating inflammatory disorders. Cytokine 142, (2021).

Wang, X. et al. Genomic G-quadruplex folding triggers a cytokine-mediated inflammatory feedback loop to aggravate inflammatory diseases. iScience 25, (2022).

Acknowledgements

We wish to extend heartfelt thanks to Ms. Fiorella Masiello (Trenitalia) for providing the necessary logistic resources without which this study would not have been possible.

Funding

Partially supported by Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche - CNR (project DBA.AD005.225-NUTRAGE-FOE2021). We acknowledge co-funding from Next Generation EU, in the context of the National Recovery and Resilience Plan, Investment PE8 – Project Age-It: “Aging Well in an Aging Society” [DM 1557 11.10.2022].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing—original draft. ES: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing—original draft. RE: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, visualization. GS: Data curation, Project administration Software, Supervision, Validation, Writing—review & editing. FP: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Validation, visualization. AP: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation. RC: Data curation, visualization. SDM: Supervision, validation, Writing—review & editing SC: Supervision, validation, Writing—review & editing. BD: Conceptualization, Supervision, validation, Writing—review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mirra, D., Salvati, E., Esposito, R. et al. Cigarette smoke destabilizes G-quadruplex structures and antagonizes G4-ligand effects in macrophages. Sci Rep 16, 3988 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34041-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34041-z