Abstract

Rainfall-driven hazards such as landslides, debris flows, and earthen dam failures often arise when water changes the internal strain within sand. This study evaluates the ability of distributed acoustic sensing to monitor these strain changes in real time. We embed a fiber-optic cable in a sand-filled glass cylinder and run controlled dry- and wet-sand experiments to measure how strain develops as water infiltrates, saturates, and drains from the sand. The sensing system detects uneven water movement in dry sand and enables millimeter-scale estimates of infiltration rates, and in wet sand it tracks rising water levels, delayed strain peaks after saturation, and abrupt strain shifts during drainage. These results show that fiber-optic sensing captures subtle strain evolution throughout the full water-sand interaction cycle. The study demonstrates that fiber-optic sensing offers promising potential for real-time and cost-effective monitoring and early warning of rainfall-induced geohazards.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Landslides, mudslides, debris flows, cliff collapses, and earth dam failures are among the most destructive geohazards worldwide, causing about 5000 deaths each year1,2,3. Their occurrence is unevenly distributed, with Asia experiencing the highest frequency1. Triggers range from natural processes such as intense rainfall, earthquakes, and volcanic activity to human-induced factors including construction, deforestation, and mining1. Notable disasters include the 2001 Las Colinas landslide in El Salvador4, the 2024 Meizhou highway collapse in China5, and deadly cliff failures in California (2019)6 and Brazil (2022)7.

Backward erosion piping—where seepage removes soil and piping surges accelerate erosion—is the most dangerous failure mechanism for earthen dams and levees. Historic and recent disasters include the 1976 Teton Dam failure in the U.S.8 and the 2024 Dongting Lake Dam breach in China9.

Overall, these hazards share a common link: strain evolution driven by water–sand interactions. Real-time monitoring of these processes is essential for early warning, risk mitigation, and reducing loss of life, infrastructure damage, and environmental impacts.

Traditional landslide monitoring has advanced significantly over the past 50 years through mapping, remote sensing, geotechnical and geodetic instruments, and hydrogeological measurements10,11,12. These methods provide valuable geological, geomorphological, and hydrological data, but most rely on discrete sensors that are sparsely deployed, limiting spatial coverage, temporal continuity, and subsurface resolution. While new approaches such as wireless sensor networks13,14 and machine learning15 have been proposed, a real-time and cost-effective system with high spatial resolution remains lacking.

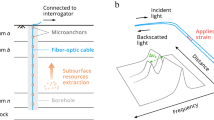

Distributed Acoustic Sensing (DAS) offers a promising solution by enabling continuous, high-resolution monitoring of strain responses over long fiber lengths16,17,18, filling a critical gap in tracking internal strain evolution associated with water–sand interactions. Fiber-optic Distributed Acoustic Sensing (DAS) is emerging as a transformative technology for real-time, efficient, and cost-effective landslide monitoring. By transmitting laser pulses through optical fibers and analyzing Rayleigh backscattering, DAS continuously measures dynamic strain along fibers up to 50 km long with meter-scale resolution and broad frequency sensitivity18,19. Fibers can be deployed in boreholes, trenches, or seafloors19,20, providing dense, real-time monitoring beyond the capability of traditional methods.

Field studies, such as the British Geological Survey’s Hollin Hill Landslide Observatory, have shown that DAS can detect strain evolution, velocity changes, and rainfall-induced slope instability with nanostrain-rate sensitivity21,22,23,24. Research demonstrates DAS’s ability to capture landslide processes from slow creep to rapid failure and to correlate seismic velocity variations with rainfall events25. Advanced machine learning methods further enhance DAS applications, achieving > 95% precision in detecting precursory rock collapses in Switzerland26.

Beyond landslides, DAS is increasingly applied to monitor rockfalls27, dam failures28, and coastal landslides29. Its combination of wide spatial coverage, real-time transmission, and integration with existing fiber-optic networks makes DAS a powerful tool for geohazard early warning and risk mitigation.

Laboratory-scale DAS experiments provide a cost-effective and controlled way to study landslide processes, offering faster insights than field surveys by simulating long-term behavior within short timeframes. Recent studies have demonstrated DAS’s ability to detect seismic events in sandpile experiments30 and to monitor strain evolution in sand–fiber systems influenced by water–sand interactions31. Building on this work31, dry- and wet-sand experiments reveal that DAS can capture different stages of water behavior—dripping, rising, holding, and draining—highlighting its potential for monitoring strain evolution and supporting geohazard early warning and risk mitigation.

Results

DAS instrumentation setup

The study uses laboratory-scale distributed acoustic sensing (DAS) experiments to measure and monitor strain variations caused by water–sand interactions. The setup consists of a DAS interrogator unit (IU), ODiSI 6101, and a 2.28-m optical fiber embedded in a glass cylinder filled with either dry (Fig. 1a) or wet sand (Fig. 1b). In the dry-sand experiment, water is dripped from an inverted plastic bottle onto the center of the cylinder (Fig. 1a). For the wet-sand experiment, a water control system is designed to regulate inflow and outflow to the water tank (Fig. 1b).

A central component is the sand–fiber system (Fig. 1c), in which the 2.28-m fiber, enclosed in a protective sleeve, is installed inside the glass cylinder (7.2 cm diameter, 31 cm height), together with six vertical reference fibers (labeled 1–6). Table 1 lists the distances between the six fiber segments, as well as their distances to the water-drip point in the dry-sand experiment. The fiber is routed through the sand cylinder using simple supports to avoid sharp bends. Specifically, the main fiber is routed through two circular cardboard guides located at the bottom (points A, C, and E) and top (points B and D) of the cylinder. To avoid sharp bends, five plastic bottle caps are placed at positions A–E as supports. Starting from the origin (O), the fiber sequentially connects with reference fibers #1 through #6 by descending and ascending between points A–E (Fig. 1c). This design enables continuous monitoring of strain evolution along six vertical segments within the cylinder.

DAS operates by transmitting laser light through the fiber and analyzing Rayleigh backscattered signals to detect distributed axial strain. While OTDR (optical time-domain reflectometer)-based DAS is suited for large-scale, dynamic field monitoring, this study employs OFDR (optical frequency-domain reflectometer)-based DAS because of its superior spatial resolution and sensitivity—ideal for resolving slow, small-scale strain changes in a laboratory setting. The ODiSI 6101 supports distributed strain sensing (and optionally temperature), but only strain is measured here due to budget constraints. A single strain channel with 2.6 mm sensor spacing and reduced temporal sampling (from 125 Hz to 2 Hz) is used to balance resolution, noise, and data volume.

Dry-sand experiment

The dry-sand experiment involves dripping water from an inverted plastic bottle onto a sand-filled glass cylinder (Fig. 1a), while strain evolution is monitored with a DAS interrogator unit. The objective is to obtain and analyze DAS responses to water–sand interactions at six fiber locations within the sand–fiber cylinder system.

Position–strain plots (Fig. 2a) show that as water infiltrates, pulse widths at all six fiber locations expand, indicating growth of the percolation zones and advancing infiltration fronts. The process is clearly three-dimensional and non-uniform, influenced by sand heterogeneity and fiber position relative to the water entry point. The largest compressive strains occur at the bottom support points A, C, and E (Fig. 2a, bottom frame), likely from the added water mass, while buoyant forces on fine grains contribute to a dynamic balance in strain distribution (upward arrows in Fig. 2a, bottom frame).

Strain time series (Fig. 2b) at fiber positions #1 and #2 reveal temporally increasing pulse widths, consistent with the downward migration of water fronts. These dynamic strain responses enable spatially and temporally resolved tracking of infiltration at all six fiber locations. Time–pulse width measurements define the depths affected by percolation and allow calculation of infiltration rates as functions of both time and depth. Results quantitatively highlight the three-dimensional, depth-dependent, and spatially variable nature of the infiltration process. Because the experiment lacks co-located moisture and pore-pressure sensors, these pulse widths should be interpreted as relative indicators of strain-affected zones along the fiber rather than absolute measures of wetting-front depth.

This dry-sand experiment demonstrates that DAS strain measurements can quantify strain amplitudes and provide continuous, high-resolution monitoring of the spatial and temporal evolution of water–sand interactions. The approach offers a novel method for quantifying infiltration dynamics and has direct relevance to water-related geohazards using DAS technology.

Wet-sand experiment

Geohazards such as landslides and piping surges are often triggered by the rapid saturation of sand or soil. Because these processes involve strong water–sand interactions, Distributed Acoustic Sensing (DAS) can play an important role in tracking strain variations during the transition from partially saturated to fully saturated conditions. Monitoring these changes in real time is critical for early warning and risk reduction. To explore this capability, we design a wet-sand experiment building upon the earlier dry-sand tests, with the goal of evaluating the effectiveness of DAS for monitoring spatiotemporal strain evolution during infiltration, full saturation, and subsequent drainage.

The instrument setup (Fig. 1b) for the wet-sand experiment uses the same interrogator unit and 2.28-m fiber with six embedded vertical segments as in the dry-sand test, but with modifications to allow controlled water exchange from the base of the wet-sand cylinder. The wet sand-filled glass cylinder is placed in a rectangular water tank connected by a pipe to a laboratory tap and sink, enabling both inflow and outflow control (Fig. 1b). To permit upward infiltration and downward drainage, the sealed baseplate from the dry-sand setup is replaced with a permeable membrane supported by a metal ring bracket that elevated the cylinder about 4 cm above the tank base. This design retained the sand while allowing water to rise into or drain out of the cylinder, thereby simulating natural saturation and drainage processes.

The fiber layout is shown in Fig. 1c. Endpoints O and P are used for calibration taps. Six vertical fiber segments are distributed throughout the sand column, with odd-numbered segments running downward (#1, #3, #5) and even-numbered ones upward (#2, #4, #6). Five support points (A–E) prevented bending; those at the base (A, C, E) are expected to experience compressive strains from water loading, while the upper supports (B, D) are less affected.

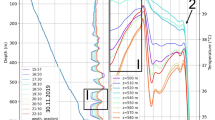

The experiment proceeds in three stages (Fig. 3). Water input begins at 15:36, raising the water level gradually until the tank is full at 16:36 (water-rise phase, 60 min). The water level is then held constant for 55 min (water-hold phase, until 17:31) before drainage begins via the sink outflow (drainage phase, 119 min). The total duration is nearly four hours, with continuous DAS monitoring throughout.

To analyze strain evolution during the wet-sand experiment, DAS data from the ODiSI 6101 interrogator unit are processed into waterfall plots (Fig. 3). In these plots, the horizontal axis represents fiber length (mm), the vertical axis time (min), and the color scale strain amplitudes (− 4 to 14 µɛ). Calibration taps appear at O and P, while support points A–E and the six vertical fiber segments provide distributed strain measurements within the wet-sand cylinder.

Water-rise phase (15:36–16:36): As the water level in the tank increased from 0 to 28 cm, strain amplitudes across the six fiber segments gradually increased (Fig. 3), shifting from near-zero (blue) to higher values (green–red). The advancing water–sand interaction zones are evident in the sloping trajectories of each fiber segment, from which average infiltration rates can be estimated. Segments close to the cylinder wall (#2, #3, #5) record stronger strain signals than those toward the center (#1, #4, #6), reflecting preferential infiltration along the boundary. At bottom supports A, C, and E, strain cycled upward and downward due to competing gravitational and buoyant forces, whereas top supports B and D remained nearly flat.

Water-hold phase (16:36–17:31): After the tank is filled, external input stops, but strain amplitudes continue to grow for ~ 30 min before stabilizing (Fig. 3), indicating a delayed transition from partial to full saturation. This lag suggests a time-dependent redistribution of water within the pore spaces, which could serve as an early-warning signal in natural geohazard systems. Peak strain values are most pronounced at segments #2, #3, and #5 and at bottom supports A, C, and E, consistent with the added water weight. Two brief, small-amplitude anomalies (90–105 min) spanning the entire fiber length were detected, most likely caused by unintentional external disturbance. While checking the water input/output system in preparation for the drainage phase, we may have lightly contacted the exposed black portion of the fiber (Fig. 1) that connects to the IU. After these two small pulses, the strain amplitudes returned to the consistent trend observed throughout the experiment. Therefore, these disturbances do not significantly affect the identification of the delayed peaks or the transition into the drainage phase.

Water-drainage phase (17:31–19:30): Once drainage began, strain amplitudes gradually decreased across all six fiber segments, as illustrated in Fig. 3 by the transition from red to blue, reflecting the progressive drop in water level as water exited the system. Segments #2–#5 responded immediately, while #1 and #6 show a lag, probably reflecting slower drainage in the central sand zone. Two abrupt strain variations are observed: a small overshoot immediately after drainage begins and a sharp drop ~ 20 min later, suggesting that rapid water-level changes may destabilize a fully saturated sand system. At supports A, C, and E, strains steadily decreased to baseline, reflecting removal of water load, while B and D remained consistently low.

Overall, the DAS waterfall plots clearly resolve the progression of infiltration, delayed saturation, and drainage within the wet-sand system, capturing both gradual and abrupt strain changes. These observations confirm the ability of DAS to monitor subtle hydro-mechanical processes relevant to water-saturation-related geohazards, demonstrating its potential for early detection and risk mitigation.

We illustrate the spatial strain evolution in six fiber segments across the entire wet-sand experiment (Fig. 4a), covering the water-rise (Fig. 4b), water-hold (Fig. 4c), and water-drainage (Fig. 4d) stages. Each four-panel plot shows fiber length vs. strain (left, horizontal axis = fiber length in mm, vertical = strain in µε) and corresponding waterfall plots for segment #3 (right), used as a representative example of spatiotemporal strain changes. Colored numbers (1–6) mark the fiber segments, letters (A–E) the support points, and spikes at O and P are calibration signals. In Figs. 4a and 25 colored curves capture strain profiles at selected times.

Water-rise phase (0–60 min): Nine color-coded curves (Fig. 4b) show progressive strain buildup. A flat profile at 0.5 min (blue) develops distinct peaks at bottom supports A, C, and E by 7 min. With rising water, these pulses broaden and split into double peaks around 15 min, reaching maximum widths across all six segments by 60 min.

Water-hold phase (60–115 min): Five curves (Fig. 4c) display six distinct strain pulses, each tied to a fiber segment. Although no more water entered, amplitudes continue to rise for ~ 30 min, peaking near 90 min, then slowly decline. This lag reflects the transition from partial to full saturation and may be a critical early-warning indicator in natural systems. Bottom supports (A, C, E) show high amplitudes due to gravitational and buoyant forces, while top supports (B, D) record weaker, downward-directed strains.

Water-drainage phase (115–234 min): Eleven curves (Fig. 4d) show steadily declining amplitudes as the water level fell, with pulses fading to near zero at supports A, C, and E. The experiment duration is insufficient to confirm full recovery to pre-experiment baselines.

Time-lapse analyses of all six fiber segments further illustrate the phase-specific strain dynamics. In particular, across all segments we observed ‘delayed strain peaks’ during the hold stage, followed by a ‘strain overshoot’ and a ‘sharp drop’ during the drainage phase. Fiber segment #2 (Fig. 5) is used as an example to describe these observations in detail. During the rise, strain increased sharply as water reached successive fiber depths. In the hold phase, amplitudes continue to grow, peaking ~ 30 min later, then decline gradually. During drainage, amplitudes decreased overall, with two abrupt changes: a small overshoot immediately after drainage begins (red arrow, Fig. 5a) and a sharp drop ~ 20 min later (black arrow, Fig. 5a). Extrapolation suggests near-zero strain would have been reached ~ 75 min after the experiment ended.

For consistency, we refer to the three principal transient strain features as: (1) the delayed strain peak occurring during the hold phase, (2) the strain overshoot immediately after drainage begins, and (3) the sharp strain drop approximately 20 min into drainage.

Unlike the dry-sand experiment, where strain primarily track localized infiltration fronts, the wet-sand setup captured the full cycle of water rise, delayed saturation, and drainage. The observed time lag before peak strain and the abrupt strain drops during drainage highlight processes unique to fully saturated systems, underscoring their added complexity and hazard potential compared to partially saturated sand.

The wet-sand experiment shows that DAS can resolve fine-scale strain dynamics across all infiltration stages. Key findings include:

-

Delayed peak strains during hold — strain continues to accumulate even after inflow stops, reflecting slow redistribution as sand transitions to full saturation.

-

Support-point sensitivity — higher strains at the base supports (A, C, E) reflect gravitational loading and buoyancy balance, while upper supports respond more weakly.

-

Heterogeneous responses — wall-adjacent fibers detect earlier and stronger infiltration than central fibers, revealing three-dimensional flow effects.

-

Abrupt transients during drainage — sudden overshoots and drops indicate that rapid water removal can destabilize saturated systems.

Together, these results confirm DAS as an effective tool for tracking strain evolution in wet sand and provide a controlled laboratory analogue for hydro-mechanical processes that drive water-related geohazards.

Discussions

We used DAS waterfall plots and strain-versus-length/time graphs to show that the DAS instrument, coupled with the sand-fiber system, effectively monitors spatiotemporal strain evolution during water rise, hold, and drainage. The system achieves high resolution (2.6 mm, 2 Hz sampling), capturing both gradual and abrupt strain changes linked to water–sand interactions.

Implications for geohazard monitoring

As quantified in the Results section, strain continues to accumulate for about 30 min after the water tank is full, reflecting delayed hydro-mechanical adjustment within the saturated sand column. This delayed strain response suggests a time lag between the partially and fully water-saturated states of the water-sand system, which may offer valuable lead time for early warning indicators of instability. Our wet-sand experiment also reveals two abrupt strain changes during the water-drainage stage: an initial strain overshoot of approximately 1 microstrain immediately after drainage begins and a sharp strain drop of about 2 microstrain occurring 20 min later. To prevent potential damage or collapse of the vulnerable water-sand system, a sudden drop in water level should be avoided when strain amplitudes are near their peak during the water-hold stage, as the additional overshoot may exacerbate stress conditions. The cause of the sharp strain drop remains unclear, but its implications for system stability warrant further investigation.

The delayed strain peak observed approximately 30 min after water input stops can be attributed to the well-known wetting-front lag phenomenon in unsaturated-soil infiltration. In rainfall-infiltration column experiments, Montoya-Dominguez et al. (2017)32 showed that volumetric water content at depth increases only after a measurable delay (‘lag time’), reflecting the downward advance of the wetting front and the diffusive redistribution of pore water governed by matric suction and unsaturated permeability. This lag time represents the interval required for the wetting front to reach a given depth and is an intrinsic hydraulic response of partially saturated soils. After external inflow ceases, water continues to redistribute, causing pore-water pressures to rise, effective stress to decrease, and compressive strain to continue increasing—consistent with the delayed strain peak detected by the DAS system. This behavior aligns with pore-pressure diffusion concepts widely applied in landslide hydrology and may serve as a useful early-warning indicator of subsurface wetting.

The abrupt strain drop immediately after drainage begins can be interpreted as a rapid hydro-mechanical transition driven by the sudden loss of matric suction and the collapse of capillary bridges. Tensile-strength measurements in unsaturated sands by Lu et al. (2007)33 show that capillary-induced tensile stress decreases sharply during drainage, producing sudden reductions in apparent cohesion and rapid rearrangement of the granular skeleton. Complementary rheological experiments by Chang et al. (2025)34 demonstrate that in wet granular media near saturation, even small decreases in water content can trigger abrupt strength reductions as loosely packed, capillary-supported grain networks collapse. When drainage starts in our experiment, pore-water pressure near the outlet drops toward atmospheric levels more quickly than the grain skeleton can mechanically adjust. This imbalance causes a rapid increase in effective stress and localized compaction. The resulting hydro-mechanical ‘drainage shock’ is therefore consistent with both unsaturated-soil tensile-strength behavior and capillary-controlled instabilities in wet granular systems.

The combined effects of wetting-front lag and abrupt capillary collapse indicate that hydrologically driven strain evolution in partially saturated sand is governed by both diffusion-controlled pore-pressure changes and nonlinear capillary-driven transitions. The lagged infiltration response documented by Montoya-Dominguez et al. (2017)32, together with the abrupt shear-strength shifts reported by Chang et al. (2025)34, demonstrates that such hydro-mechanical delays and discontinuities are intrinsic to wet granular materials and directly relevant to rainfall-triggered landslide processes. The high sensitivity of the DAS system to these transitions suggests that delayed strain peaks and drainage-related strain drops may serve as physically grounded precursory indicators of hydrologic forcing and potential instability in natural slopes.

Our experiments demonstrate that strain remains near zero without water–sand interaction, but rises sharply—up to ~ 15 µε—when sand transitions from partial to full saturation. Rising water expands the affected zones, while holding water leads to delayed strain peaks, and drainage causes a gradual return toward zero. This delayed peak response may serve as an early-warning indicator for instability. These findings underscore DAS as a powerful tool for monitoring water-saturation-driven hazards such as landslides, piping surges, and dam failures. For example, fibers placed in L-shaped wells or embedded horizontally in sand layers could track advancing water fronts for early warning.

These laboratory observations demonstrate that DAS captures the full hydro-mechanical response of water–sand systems, from infiltration through delayed saturation to drainage, providing a mechanistic basis for interpreting similar precursory signatures in natural slopes.

Challenges and limitations

In this study, we rely solely on DAS. Integrating DTS would provide complementary temperature information, as demonstrated in hydraulic fracture monitoring where strain increases correlate with temperature decreases35,36. Because OFDR is highly sensitive to temperature, we maintained both water and sand at a controlled room temperature of approximately 70 °F throughout the dry- and wet-sand experiments (each lasting several hours) to minimize thermal-strain noise. In future laboratory sand experiments, incorporating DTS will allow us to track temperature variations and quantify thermally induced contraction and expansion of the fiber. For future field applications, simultaneous DAS–DTS measurements will be essential for monitoring changes in water temperature and the advance of wetting fronts.

Another major limitation of the present study is the lack of accurate, independent calibration of the absolute positions of the fiber segments relative to the internal wetting front. In the wet-sand experiment, although the external water level was monitored, the internal water level within the sand column could not be measured directly. In the dry-sand experiment, visual observations show irregular downward movement of the wetting front along the glass cylinder wall, but its internal position relative to the six fiber segments is not independently known. Installing TDR moisture sensors or pore-pressure transducers collocated with the fiber segments would provide independent measurements of wetting-front position, enabling absolute quantitative calibration. Without such calibration, the pulse width and inferred wetting-front positions should be interpreted primarily as relative rather than absolute indicators of infiltration depth.

Overall, this study demonstrates that distributed acoustic sensing provides a physically grounded, high-resolution means for monitoring real-time hydro-mechanical changes in sand systems. The controlled laboratory findings presented here establish a foundation for scaling DAS techniques to field environments where early detection of rainfall-induced geohazards is critical.

Future directions and applications

The insights gained from our laboratory experiments are ultimately intended to address real geohazard monitoring challenges, but bridging the gap between laboratory and field conditions requires careful consideration. Comparing DAS installation conditions in both environments helps clarify this transition. In our laboratory setup, the fiber is only loosely coupled to dry or wet sand, which leads to relatively lower SNR. In contrast, field installations typically involve cementing the fiber-optic cable to the outside of a borehole casing or directly burying it in a trench—both methods that provide much stronger mechanical coupling. Consequently, strain-transfer efficiency and measurement SNR in the field are generally expected to exceed those in our loosely coupled laboratory tests, enabling high-quality DAS data acquisition.

We observe “delayed strain peaks,” “strain overshoots,” and “strain sharp drops” consistently across all six fiber segments, demonstrating spatial repeatability. However, additional wet-sand experiments will be required to further validate the repeatability of these phenomena in the time domain.

In future laboratory and field DAS experiments aimed at monitoring water–sand interactions, we plan to install TDR moisture sensors or pore-pressure transducers collocated with the DAS fibers to provide independent measurements of the wetting-front position. Such co-located sensing will enable absolute calibration of the DAS strain response and allow us to establish a more accurate and quantitative relationship between wetting-front position and strain-amplitude anomalies.

Accurate prediction of landslides and debris flows requires the ability to capture the earliest, extremely small acceleration signals, which are critical for precise failure-time forecasting. The transitional behavior during accelerating creep is particularly important, yet it is often difficult to detect. Studies of fast–slow transitions in accelerating creep of clayey soils induced by elevated pore-water pressure reveal pronounced transitional behavior and frequent deviations from empirical prediction models in many cases37,38. These findings highlight the importance of recognizing the transitional stage prior to failure when designing effective early-warning strategies. Such considerations should be fully incorporated into early-warning frameworks based on continuous DAS monitoring systems.

Scientists have long sought to predict landslide motion through pore-pressure and hydrological monitoring; however, in some cases, the observed kinematics are not fully consistent with hydrological conditions alone. Schulz et al. (2017)39 illustrated the complexity of landslide behavior across multiple timescales and emphasized the need to integrate diverse data sources. Studies by Liu et al. (2025)40 and Xu et al. (2011)41 further demonstrate that irrigation activities can induce landslides. Extending fiber-optic sensing to the monitoring of irrigation-induced landslides therefore represents a promising direction for future research. Comprehensive integration of observations, continuous monitoring, physical interpretation, and real-world applications—using DAS systems in combination with conventional hydrological monitoring tools—will substantially advance landslide early-warning capabilities.

Beyond hazard monitoring, DAS infiltration analysis could support agriculture (e.g., irrigation management) and civil engineering (e.g., leak detection). Recent work shows DAS can resolve vadose-zone soil moisture changes42, highlighting its versatility.

Methods

Sand properties

The sand used in the glass cylinder of our sand-fiber system—employed in our experiments—has several measured and analyzed properties, including grain size distribution, bulk density, and porosity. Grain size analysis (Table 2) reveals that the sample consists of 0.34% silt or clay (grain size < 0.0625 mm), 23.5% very fine sand (0.0625–0.125 mm), 75.7% fine sand (0.125–0.25 mm), and 0.27% medium sand (> 0.25 mm). The measured bulk density is 1630 kg/m³, and the estimated porosity ranges from 41.3% to 44.7% (Table 3), indicating that the dry sand is predominantly (over 99%) composed of fine to very fine grains and is loosely packed.

DAS interrogator selection

The DAS interrogator employs a laser source to transmit optical signals through the fiber and analyzes Rayleigh backscattered light—caused by microscopic imperfections within the fiber—to measure distributed axial strain or strain rate (i.e., acoustic and vibrational signals) along its entire length. DAS systems typically operate using one of two core principles: Optical Time Domain Reflectometer (OTDR) or Optical Frequency Domain Reflectometer (OFDR). OTDR-based DAS transmits light pulses over distances of tens of kilometers with high temporal sampling rates, making it well suited for large-scale, cost-effective monitoring of dynamic geohazards such as landslides, earthquakes, and volcanic eruptions. In contrast, OFDR-based DAS uses continuous-wave light sources in the frequency domain, offering higher sensitivity and finer spatial resolution, but at lower sampling rates. For our confined laboratory setup, where centimeter-scale strain changes develop slowly during water infiltration, OFDR provides the optimal balance of resolution and sensitivity.

In this study, we use a high-definition Optical Distributed Sensor Interrogator (ODiSI) 6101, developed by Luna Innovations (Fig. 1a, b), which operates on the OFDR principle. The system measures distributed axial strain along an optical fiber using Rayleigh backscatter. Although the ODiSI 6101 outputs strain rather than strain rate, we refer to it as a DAS interrogator rather than a Distributed Strain Sensing (DSS) unit to distinguish it from DSS systems based on Brillouin scattering. The ODiSI 6100 series also supports distributed temperature sensing (DTS) via Rayleigh backscatter, differing from Raman-based DTS systems. The ODiSI 6101 model allows up to eight parallel channels, enabling simultaneous DAS and DTS measurements with separate fibers; however, due to budget constraints, our unit is limited to a single channel and strain-only measurements. We note that concurrent DAS and DTS measurements would provide valuable additional insights into water–sand interactions in our future similar experiments.

For our experiments, we connect the single-channel ODiSI 6101 interrogator to a 2.28-m optical fiber embedded in a glass cylinder filled with either dry or wet sand. The interrogator supports a temporal sampling rate of up to 125 Hz and includes built-in downsampling. Sensor spacing can be configured at 0.65 mm, 1.3 mm, 2.6 mm, 5.6 mm, or 10.4 mm, with gauge length set either to the chosen spacing or to > ± 3 times that value. If the adjustable parameter is set to zero, gauge length equals sensor spacing. Tests confirm that all spacing parameters perform well, including the minimum 0.65 mm, but the default 2.6 mm spacing provided the best signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). In Fig. 6, we compare the SNR of DAS strain traces from three tests acquired with sensor spacings of 0.65 mm, 1.3 mm, and 2.6 mm. The overall waveform characteristics and trends are consistent across all three datasets, indicating good repeatability of the strain measurements. However, we observe a substantial increase in high-frequency noise as sensor spacing decreases from 2.6 mm (Fig. 6c) to 0.65 mm (Fig. 6a). The smallest spacing introduces numerous high-frequency, random glitches, suggesting that strain measurements become less stable at this resolution. Based on these comparisons, we conclude that the default 2.6 mm sensor spacing of the interrogator provides the most reliable and stable measurements for our experiments. Accordingly, we adopted 2.6 mm spacing with gauge length equal to the spacing. During the dry-sand experiment, we used the default temporal sampling rate of 125 Hz, but because water–sand strain evolution is relatively slow, we reduced the rate to 2 Hz with downsampling to minimize data volume in the wet-sand experiment.

DAS data processing

For the dry-sand experiment, we directly plotted the recorded strain data in selected time windows to illustrate the temporal evolution shown in Fig. 2. No additional preprocessing—such as detrending, filtering, or baseline correction—was applied. This decision avoids inadvertently removing low-frequency components that may reflect real strain contributions from the base supports (A, C, and E) or the hydro-mechanical balance between sand gravity and water buoyancy. Minimal preprocessing was used to avoid filtering out low-frequency strain variations associated with hydro-mechanical processes, which are essential to interpreting infiltration and drainage dynamics.

For the wet-sand experiment, we downsampled the temporal sampling rate to 2 Hz. Inspection of the strain–length records revealed that waveform shapes remained nearly unchanged within any given 30-second window. To enhance SNR, we therefore stacked the data over each 30-second interval, improving SNR by a factor of approximately 7.7 and reducing random, uncorrelated strain noise. The stacked records were then used to construct the waterfall plot in Fig. 3.

Infiltration process visualization

During the dry-sand experiment, DAS strain time series (Fig. 2b) display progressively widening pulse widths, reflecting the downward migration of water percolation fronts through the sand matrix. The broadening strain signatures indicate an increasing depth of mechanical coupling between the hydro-logically disturbed sand and the optical fiber. These dynamic responses enable both spatially and temporally resolved tracking of the infiltration front across all six sensing locations. Synchronized visual observations of the dry sand–fiber cylinder (Fig. 7) corroborate the DAS-based interpretations (Fig. 2b), clearly showing the downward advance of the water front.

In the wet-sand experiment, strain evolution during the water-rise phase is analyzed across different fiber positions (Fig. 8a) and compared with synchronized snapshots of external water level changes (Fig. 8b). At this stage, water is added to the surrounding rectangular tank via a laboratory tap, starting at 15:36. While the tank water level remained below the 4 cm thickness of the metal ring bracket, no strain responses are detected at any of the six fiber positions, as no direct water–sand interaction occurs.

At 15:43, roughly seven minutes after water input began, the tank water level reached 5 cm (red arrow in Fig. 8b), and the strain-position curve shows three distinct positive pulses. As the water continued rising to 6 cm and then to 12 cm, the pulses broadened and their amplitudes increased. Forty-one minutes into the experiment, when the water level reached 20 cm, the three pulses split into six, with noticeably wider widths and stronger amplitudes. By 16:36–60 min after water input began—the tank is full (28 cm water depth), and six well-defined pulses are observed, each exhibiting further broadening and amplification.

Infiltration rates

In the dry-sand experiment, we measure time intervals and corresponding pulse widths—representing depths affected by water percolation—at six fiber positions and summarized the results in a time–depth plot (Fig. 9a), using distinct symbols for each location. These measurements are then used to calculate infiltration rates (IR) as functions of both time (Fig. 9b) and depth (Fig. 9c). Across the six fibers, infiltration rates ranged from 1.0 to 1.5 mm/min (Fig. 9a, b), highlighting the three-dimensional nature of the infiltration process with depth-dependent and spatially varying characteristics. This dry-sand experiment demonstrates that DAS-based strain measurements can quantify strain amplitudes and enable continuous, high-resolution monitoring of the spatial and temporal evolution of water–sand interactions—one of the key mechanisms underlying certain water-related geohazards. Furthermore, the experiment introduces a novel DAS-based method for calculating millimeter-scale infiltration rates during the transition from dry to wet sand.

During the wet-sand experiment, infiltration rates and their standard deviations are determined from time-versus-fiber-length (depth) plots for six fiber segments (Fig. 10). In these plots, the horizontal axis represents time (minutes), while the vertical axis shows fiber length (millimeters), corresponding to the depth of each vertically embedded segment. Average infiltration rates are derived from the slopes of fitted straight lines, and standard deviations are estimated from rate variability. Rates ranged from 4.27 to 5.25 mm/min across the six locations. Segments #1, #3, and #5, oriented against the direction of water flow, show lower rates (4.27–4.69 mm/min), whereas #2, #4, and #6, align with the flow, exhibit higher rates (5.04–5.25 mm/min). These results underscore the three-dimensional variability of infiltration in the wet-sand matrix as it transitioned to saturation, reflecting spatial heterogeneity captured by the distributed fiber array.

To directly compare conditions, we analyzed infiltration rates (IR, in mm/min) and standard deviations (σ) for the six fiber segments in both dry and wet experiments (Fig. 11a). Infiltration rate ratios (IRR), representing relative increases from dry to wet sand, are presented in Fig. 11b. The results show that infiltration in wet sand is, on average, about four times faster than in dry sand. The slower infiltration in dry sand—together with factors such as compacted desert soils and the absence of organic matter to retain moisture—helps explain the occurrence of geohazards such as desert flash flooding.

Supporting evidence comes from field-scale DAS studies. Shen and Zhu (2025)43 reported that phase velocity variations are inversely correlated with subsurface water fluctuations and that hysteresis exists between phase velocity and water content during drying and wetting cycles. They interpret this hysteresis as the result of fluid redistribution within pores and the opening or closure of microcracks as moisture conditions change. Their findings align with our laboratory observation that infiltration proceeds more slowly in dry sand than in wet sand.

The DAS-based method used here to calculate infiltration rates in dry and wet sands can be extended to other soils and materials. Beyond geohazard research, DAS monitoring of water infiltration shows promise for agricultural applications, such as tracking irrigation to optimize water use. Although outside the scope of this study, this represents an important direction for future work. For example, Sen et al. (2024) demonstrated the use of DAS to characterize soil moisture dynamics in the vadose zone of semi-arid regions. Given the high sensitivity of DAS to waterfront movement shown in our experiments, another promising application lies in civil engineering—for detecting and precisely locating underground water leaks.

Instrumentation setup of the DAS-sand-fiber system. (a) Dry-sand setup, consisting of a DAS interrogator (red rectangle A), a sand-filled cylinder embedded with 2.28 m of optical fiber, and an inverted plastic bottle (yellow rectangle B) used to drip water onto the top of the cylinder. (b) Wet-sand setup, where the sealed plastic plate from the dry-sand test is replaced with a permeable plastic membrane, allowing water to enter through the cylinder base. The cylinder is mounted on a 4-cm-thick metal ring bracket, enabling upward water flow from the surrounding tank. A water pipe connected to the laboratory tap and sink forms the water input/output (I/O) system, which regulates water rise and drainage in the tank. (c) Sand–fiber system showing the start and end points (O and P) of the optical fiber (top) and the orientations of the six vertical fiber segments (bottom). Odd-numbered segments (#1, #3, and #5) descend, while even-numbered segments (#2, #4, and #6) ascend. Support points (A–E) prevent sharp bends in the fiber that could otherwise cause breakage.

Fiber position–strain distribution plots. (a) Fiber length (m) is shown on the horizontal axis and strain (µε) on the vertical axis. Colored horizontal arrows with numbers on the top indicate the positions of the six vertical fiber segments. At 14:29:30, six distinct negative strain pulses appear, each corresponding to one of the six vertical fiber sections, with measurable pulse widths. By 15:17, the widths increase, though not uniformly across all fiber positions. Downward bending of the strain curve is observed at bottom support points A, C, and E due to the added weight of percolated water, while no significant strain changes occur at the top support points B and D. At 16:17:47, the water–sand system reaches dynamic equilibrium between gravitational forces from water and sand (acting on support points A, C, and E) and buoyant forces (blue arrows) acting on all six fiber sections. (b) Time series of fiber position–strain distribution plots for fiber segments #1 and #2, with fiber length (m) on the horizontal axis and strain amplitude (µε) on the vertical axis. From 14:29:30 to 16:04:23, pulse widths gradually widen (highlighted by red arrows and blue dashed lines), reflecting increasing depths influenced by water percolation. The reverse-symmetric widening between segments #1 and #2 results from their opposite fiber orientations.

Waterfall plot of DAS data showing spatiotemporal strain evolution during the wet-sand experiment. The experiment consists of three phases: water rise, hold, and drainage. The horizontal axis represents optical fiber length (mm), the vertical axis shows time (minutes), and the color scale indicates strain amplitude (µε). Colored numbers and double-headed arrows mark the positions of the six fiber segments, while colored letters A–E denote the five fiber support points. The fiber start and end points are labeled O and P. For each segment, fiber length also corresponds to the depth of the vertical fiber (mm). Synchronized tank water levels (cm) are annotated along the time axis, segmented into the three experimental phases. Arrowed solid lines, color-coded by fiber segment (#1–#6), trace the downward migration of water–sand interaction zones; their slopes represent average infiltration rates. Arrowed dashed lines, also color-coded, show decreasing strain amplitudes during the drainage phase. Strain responses at the three bottom supports (A, C, and E) and strain changes at the two top supports (B and D) are highlighted with solid and dashed rectangles, respectively.

Four-panel plots showing strain evolution in six fiber segments during the wet-sand experiment. (a) Overview of all three phases—water rise, hold, and drainage—using fiber length vs. strain plots and a waterfall plot for fiber segment #3. Time-lapse variations of fiber length versus strain are shown for the full experiment (0.5 to 234 min) using 25 representative curves. b-d. Expanded views of the individual phases: (b) water rise, (c) water hold, and (d) water drainage. In each phase, the left subpanel displays fiber length vs. strain (horizontal axis: fiber length in mm; vertical axis: strain in µε), while the right subpanel shows the corresponding waterfall plot for fiber segment #3, capturing temporal variations. Colored numbers mark the six fiber segments, and colored letters A–E indicate fiber support points. Strain spikes at O and P are calibration signals produced by manually tapping the fiber at those positions.

Time-lapse strain evolution from fiber segment #2 during the three phases of the wet-sand experiment, corresponding to changes in the water level inside the cylinder. (a) Time–strain plot. (b) Corresponding waterfall plot for the same fiber segment. The red upward arrow marks a sudden strain increase immediately after the onset of water drainage, while the black downward arrow denotes a sharp strain decrease about 20 min later.

Visual documentation of water infiltration during the dry-to-wet transition. a–f. Sequential snapshots of the sand cylinder at selected times (14:29:30, 14:45:00, 15:00:00, 15:17:00, 15:30:00, and 16:17:47), illustrating the progressive downward migration of water infiltration fronts and the increasing depth of zones affected by percolation. These visual observations corroborate the strain evolution recorded by DAS along the embedded fiber.

Strain evolution and synchronized visual observations during the wet-sand experiment. (a) Time series of strain distribution along the fiber length, showing progressive broadening of strain pulse widths as the water level in the surrounding tank rises. (b) Corresponding synchronized snapshots documenting the rising tank water level and its effect on the wet-sand system inside the cylinder.

DAS-based quantification of water infiltration during the dry-sand experiment. a. Temporal variations in strain pulse widths for fiber segments #1–#6. The horizontal axis represents time (minutes), and the vertical axis shows the depth of the affected zone, expressed as pulse width (millimeters). These variations reflect the progressive influence of water percolation at different fiber positions. b-c. Calculated interval infiltration rates for the six fiber segments, derived from the pulse-width measurements in (a) Infiltration rates are plotted as functions of (b) depth and (c) time.

Time–fiber length analysis of infiltration in wet sand. Time–fiber length (depth) plots for six optical fiber segments during the water-rise phase, showing calculated infiltration rates (IR) and their standard deviations. The horizontal axis denotes time (minutes), and the vertical axis represents fiber length (millimeters), corresponding to the depth of each vertical fiber segment embedded at different positions within the wet sand-filled cylinder. The slopes of the fitted lines indicate average infiltration rates, while the variability among rates for each segment provides estimates of the standard deviations. These results illustrate the three-dimensional variability of infiltration within the wet-sand matrix as it approaches full saturation, highlighting spatial heterogeneity captured by the distributed fiber layout in the experiment.

Comparison of infiltration rates in dry and wet sand experiments. (a) Average infiltration rates (mm/min) and standard deviations (σ) for six fiber segments (#1–#6), derived from the dry-sand experiment (blue symbols/lines) and the wet-sand experiment (red symbols/lines). (b) Infiltration rate ratios (IRR) comparing dry and wet conditions: blue symbols/lines show dry-to-wet ratios, while red symbols/lines show wet-to-dry ratios. Arrows denote the mean IRR values across all six fiber segments, indicating that infiltration in wet sand is approximately four times faster than in dry sand.

Data availability

Data used in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Froude, M. J. & Petley, D. N. Global fatal landslide occurrence from 2004 to 2016. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 18, 2161–2181. https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-18-2161-2018 (2018).

Pollock, W. & Wartman, J. Human vulnerability to landslides. GeoHealth 4, e2020GH000287. https://doi.org/10.1029/2020GH000287 (2020).

Petley, D. Global fatal landslides in 2024. Eos.org. https://eos.org/thelandslideblog/fatal-landslides-in-2024 (2025).

Evans, S. G. & Bent, A. L. The Las Colinas landslide, Santa Tecla: a highly destructive flowslide triggered by the January 13, 2001, El Salvador earthquake. In Natural Hazards in El Salvador: Boulder, Colorado, Geological Society of America, Special Paper 375 (eds. Rose, W. I. et al.) 25–37 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1130/0-8137-2375-2.25.

Zheng, X. et al. Analysis of landslide on Meizhou-Dapu expressway based on satellite remote sensing. Geoenviron. Disasters. 12, 25. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40677-025-00331-x (2025).

USGS Pacific Coastal and Marine Science Center. Coastal erosion researcher quoted in news coverage of fatal California cliff collapse (2019). https://www.usgs.gov/news/coastal-erosion-researcher-quoted-news-coverage-fatal-california-cliff-collapse.

Petley, D. N. The fatal rock topple at Canyon de Furnas in Brazil. AGU Blogsphere (2022). https://blogs.agu.org/landslideblog/2022/01/10/canyon-de-furnas-1.

Barnes, M. Famous failures: revisiting major dam catastrophes. In ASDSO Annual Conference. Baltimore: Association of State Dam Safety Officials (1992). https://damfailures.org/case-study/teton-dam-idaho-1976.

Zhang, Z. et al. Comprehensive assessment of the recent dike breach at Dongting lake. Innov. Geosci. 2 (4), 100106. https://doi.org/10.59717/j.xinn-geo.2024.100106 (2024).

Whiteley, J. S., Chambers, J. E., Uhlemann, S., Wilkinson, P. B. & Kendall, J. M. Geophysical monitoring of moisture-induced landslides: a review. Rev. Geophys. 57, 106–145. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018RG000603 (2019).

Auflič, M. J. et al. Landslide monitoring techniques in the geological surveys of Europe. Landslides 20, 951–965. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10346-022-02007-1 (2023).

Casagli, N. et al. Landslide detection, monitoring and prediction with remote-sensing techniques. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 4, 51–64. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43017-022-00373-x (2023).

Das, K., Majumdar, S., Moulik, S. & Fujita, M. Real-time threshold-based landslide prediction system for hilly region using wireless sensor networks. In 2020 IEEE International Conference on Consumer Electronics - Taiwan (ICCE-Taiwan) (2020). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCE-Taiwan49838.2020.9258181.

Chaulya, S. K. et al. Landslide monitoring and prediction system using geosensors and wireless sensor network. Discov. Geosci. 2, 6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44288-024-00007-3 (2024).

Halder, K. et al. Improving landslide susceptibility prediction through ensemble recursive feature elimination and meta-learning framework. Sci. Rep. 15, 5170. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87587-3 (2025).

Mestayer, J. et al. Field trials of distributed acoustic sensing for geophysical monitoring. In 81st SEG Annual Int. Meeting Expanded Abstracts 4253–4257 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1190/1.3628095.

Miller, D. et al. Vertical seismic profiling using a fiber-optic cable as a distributed acoustic sensor. In 74th EAGE Conference and Exhibition, Expanded Abstracts, Y004. https://doi.org/10.3997/2214-4609.20148799 (2012).

Hartog, A. H. An Introduction to Distributed Optical Fibre Sensors (CRC, 2017). https://doi.org/10.1201/9781315119014.

Li, Y., Karrenbach, M. & Ajo-Franklin, J. B. Distributed Acoustic Sensing in Geophysics: Methods and Applications (American Geophysical Union and John Wiley & Sons, 2021). https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119521808.

Li, Y., Mellors, R. & Zhan, G. Distributed Acoustic Sensing in Borehole Geophysics (American Geophysical Union and John Wiley & Sons, 2024). https://doi.org/10.1002/9781394179275.

Clarkson, P. et al. Distributed Rayleigh sensing for slope stability monitoring. In Paper presented at the 55th U.S. Rock Mechanics/Geomechanics Symposium (2021).

Clarkson, P. et al. Verification of a distributed fiber optic sensing slope stability monitoring solution. In 56th US Rock Mechanics/Geomechanics Symposium (2022).

Cole, S. et al. In AGU Fall Meeting 2021. (AGU) (2021).

Cole, S., Clarkson, P., Karrenbach, M. & Yartsev, V. DAS dispersion image analysis for landslide monitoring. In SEG Technical Program Expanded Abstracts 637–641 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1190/image2022-3751838.1.

Ouellet, S. M. et al. Previously hidden landslide processes revealed using distributed acoustic sensing with nanostrain-rate sensitivity. Nat. Commun. 15, 6239. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-50604-6 (2024).

Kang, J. et al. Automatic monitoring of rock-slope failures using distributed acousticsensing and semi‐supervised learning. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2024GL110672. https://doi.org/10.1029/2024GL110672 (2024).

Xie, T. et al. Seismic monitoring of rockfalls using distributed acoustic sensing. Eng. Geol. 325, 107285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2023.107285 (2023).

Ghazali, M. F. et al. State-of-The-Art application and challenges of optical fibre distributed acoustic sensing in civil engineering. Opt. Fiber. Technol. 87, 103911. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yofte.2024.103911 (2024).

Cemiloglu, A. et al. Fiber-optic technologies for real-time monitoring of coastal landslides: a review of their role in early warning systems. Front. Earth Sci. 13, 1570413. https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2025.1570413 (2025).

Fumagalli, M. et al. In AGU Fall Meeting 2024. (AGU) (2024).

Li, Y. et al. In AGU Fall Meeting 2024. (AGU) (2024).

Montoya-Domínguez, J. D., García-Aristizábal, E. F. & Vega-Posada, C. A. One-dimensional experimental study of rainfall infiltration in unsaturated sand columns. Rev. Facult. Ingenier. 82, 74–81. https://doi.org/10.17533/udea.redin.n82a10 (2017).

Lu, N., Wu, B. & Tan, C. P. Tensile strength characteristics of unsaturated sands. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 133 (2), 144–154. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)1090-0241 (2007).

Chang, C., Ohno, K., Schulz, W. H. & Yamaguchi, T. Anomalous shear stress variation in wet granular medium: implications for landslide lateral faults. Geophys. Res. Lett. 52, e2024GL113816. https://doi.org/10.1029/2024GL113816 (2025).

Molenaar, M. M. & Barbara, E. C. Field cases of hydraulic fracture stimulation diagnostics using fiber optic distributed acoustic sensing (DAS) measurements and analyses. In Paper presented at the SPE Unconventional Gas Conference and Muscat, Oman (2013). https://doi.org/10.2118/164030-MS.

Ugueto, C. et al. Perforation cluster efficiency of cemented plug and perf limited entry completions; insights from fiber optics diagnostics. In Paper presented at the SPE Hydraulic Fracturing Technology Conference, The Woodlands, Texas, USA (2016). https://doi.org/10.2118/179124-MS.

Chang, C., Noda, H., Xu, Q., Huang, D. & Yamaguchi, T. Slow-to-fast transition and shear localization in accelerating creep of clayey soil. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2024GL111839. https://doi.org/10.1029/2024GL111839 (2024).

Chang, C. & Wang, G. Creep of clayey soil induced by elevated pore-water pressure: implication for forecasting the time of failure of rainfall-triggered landslides. Eng. Geol. 296, 106461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2021.106461 (2022).

Schulz, W. H. et al. Landslide kinematics and their potential controls from hourly to decadal timescales: insights from integrating ground-based InSAR measurements with structural maps and long-term monitoring data. Geomorphology 285, 121–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2017.02.011 (2017).

Liu, K., Huang, X. & Xu, L. Characterization of the mass transport and energy conversion of a rapid long-runout loess landslide using the finite–discrete element method. J. Geophys. Res.: Earth Surf. 130, e2024JF008032. https://doi.org/10.1029/2024JF008032 (2025).

Xu, L. et al. Landslides in the transitional slopes between a loess platform and river Terrace, Northwest China. Environ. Eng. Geosci. 17 (3), 267–279. https://doi.org/10.2113/gseegeosci.17.3.267 (2011).

Shen, Z. et al. Fiber-optic seismic sensing of vadose zone soil moisture dynamics. Nat. Commun. 15, 6432. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-50690-6 (2024).

Shen, J. & Zhu, T. Constraining water dynamics through unsaturated and saturated zones using fiber-optic seismic sensing data. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 666, 119507. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2025.119507 (2025).

Acknowledgements

D.L. and L.H. were supported by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) through the Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL), which is operated by Triad National Security, LLC, for the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) of the U.S. DOE under Contract No. 89233218CNA000001. Y.Z.’s team at the University of Houston acknowledges the funding from the Robert and Margaret Sheriff professorship that partially supports purchasing the DAS instrumentation and carrying out the lab experiment.

Funding

D.L. and L.H. were supported by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) through the Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL), which is operated by Triad National Security, LLC, for the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) of U.S. DOE under Contract No. 89233218CNA000001. Y.Z. and other UH personnel were supported by funding from the Robert and Margaret Sheriff Professorship for the University of Houston.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.L., M.S., and D.L. performed the research, designed the experiments, analyzed the data, interpreted the results, and wrote the manuscript. L.H. and Y.Z. obtained funding, discussed research ideas and results, and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Y., Sun, M., Zheng, Y. et al. Monitoring strain evolution in water-sand systems using distributed acoustic sensing for geohazard early warning. Sci Rep 16, 3949 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34069-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34069-1