Abstract

Enhancing the predictive accuracy of polygenic risk scores (PRS) can be achieved by incorporating imaging data, which captures disease-related phenotypic variations. This study aimed to evaluate the predictive performance of PRS, image-derived deep learning scores (IDS), imaging-derived phenotypes (IDPs), and clinical covariates. Additionally, IDP-proxy genetic scores (IGSs) were developed as substitutes for IDPs in cases where imaging data are unavailable. The study assessed the predictive performance of these variables for glaucoma using the XGBoost model. IDS was generated using a deep learning model trained on optical coherence tomography (OCT) images obtained from the UK Biobank. The dataset included 55,469 samples with OCT imaging data and 402,847 samples without OCT images. To accommodate cases without imaging data, IGSs were introduced as replacements for IDPs. The AUC was used to compare the performance of individual predictors and multimodal models. Among single predictors, IDS demonstrated the highest predictive performance, achieving an AUC of 0.7742, indicating its effectiveness in capturing glaucoma-related structural changes. IDPs and PRS showed lower AUCs of 0.7106 and 0.6150, respectively. The multimodal model integrating PRS, IDS, IDPs, and clinical covariates achieved the highest predictive accuracy with an AUC of 0.7921. When imaging data were unavailable, IGSs alone had a relatively low AUC (0.5467), but performance improved to 0.7397 when combined with PRS and clinical covariates, demonstrating their viability as substitutes for IDPs. This study highlights the effectiveness of deep learning-based image features in glaucoma risk prediction and demonstrates that integrating genetic, imaging, and clinical data enhances predictive accuracy. Additionally, IGSs provide a viable alternative to IDPs when imaging data are unavailable, ensuring reliable glaucoma risk assessment in resource-limited settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Polygenic risk scores (PRS) have emerged as a powerful tool for quantifying an individual’s genetic susceptibility to complex diseases by aggregating the effects of numerous genetic variants1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10. Unlike traditional genetic analyses that focus on single-gene associations, PRS captures the cumulative impact of multiple variants, offering a more comprehensive assessment of disease predisposition. This approach enhances disease risk prediction and plays a crucial role in personalized medicine, particularly for conditions with strong genetic components such as cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, neurodegenerative disorders, and autoimmune diseases. By identifying high-risk individuals, PRS facilitates early interventions and tailored preventive strategies, improving health outcomes at both individual and population levels.

Recently, the integration of PRS with clinical and imaging data has gained attention as a means to refine disease prediction models11,12,13,14,15. Imaging data such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography (CT) scans, and imaging-derived phenotypes (IDPs) provide valuable structural and functional insights into disease pathology. When combined with PRS, imaging data enhance the accuracy of personalized risk assessments by capturing early disease-associated changes that may not be detectable through genetic data alone. Traditional PRS models incorporate clinical covariates such as age, sex, and lifestyle factors, which, while informative, do not fully capture disease-related variability. The inclusion of imaging-derived features provides a more nuanced understanding of disease progression, leading to improved predictive models.

Advancements in deep learning have further expanded the role of imaging in disease prediction16,17,18. Deep learning models can extract intricate disease-specific patterns from image data, generating imaging-derived deep learning scores (IDS) that serve as novel biomarkers. These models enable the automated identification of subtle structural abnormalities linked to disease risk, making them a valuable addition to PRS-based frameworks. However, when direct imaging data are unavailable, IDP-proxy genetic scores (IGSs) can act as proxies for IDPs19. IGSs approximate IDPs using genetic predictors, allowing researchers to leverage imaging-related insights even in the absence of actual imaging data. A multimodal approach that integrates genetic scores, imaging features, and clinical covariates further enhances prediction accuracy, offering a robust framework for disease risk assessment. By combining the complementary strengths of genetic and imaging data, this approach improves risk stratification and mitigates challenges posed by missing data through alternative predictive models. This integrated strategy is driving advances in genome-based precision medicine, with significant implications for the early detection and management of complex diseases.

In this study, we apply this multimodal approach to glaucoma as a case study to demonstrate the benefits of integrating imaging-derived features and deep learning methods with PRS20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27. Using optical coherence tomography (OCT) images and genetic data, we generate IDS to capture disease-specific features, incorporate PRS to assess genetic susceptibility, and utilize IGSs as proxies for imaging-derived features when direct imaging data are unavailable. Finally, we explore a comprehensive multimodal model that integrates these elements to provide a scalable and effective solution for disease risk prediction. Through this study, we examine the potential of combining genetic, imaging-derived, and clinical data to enhance glaucoma prediction.

Methods

UK biobank

The UK Biobank is a large-scale, population-based health research resource that recruited over 500,000 individuals aged 40 to 69 between 2006 and 201020. Participants were invited through the National Health Service (NHS) and attended one of 22 assessment centers across the UK, where they provided extensive data, including genetic samples, imaging data, and detailed health and lifestyle information. The UK Biobank study was approved by the North West Multi-centre Research Ethics Committee (MREC), and all methods in this study were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. For genetic analysis, we focused on 458,316 participants of European descent with high-quality genetic data and comprehensive health and lifestyle records to ensure homogeneity. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were filtered based on a minor allele frequency (MAF) threshold > 0.01 and an imputation quality score > 0.8, resulting in a final dataset of 9,572,559 SNPs used for analysis.

Glaucoma and clinical covariates

Glaucoma cases were identified by integrating diagnostic codes and self-reported data. Participants were classified as having glaucoma if they met at least one of the following criteria: (1) an ICD-9 code of 365 or an ICD-10 code of H40 (excluding H40.01 and H42), (2) self-reported glaucoma in either the eye problems/disorders section or the non-cancer illness code section, (3) reported treatment with intraocular pressure-lowering medication, or (4) a history of laser therapy or surgical intervention for glaucoma. Among the total cohort of 458,316 participants, 13,805 individuals were identified as having glaucoma. Within the subset of 55,469 participants with OCT imaging data, 1,676 individuals met the glaucoma criteria. This comprehensive approach ensured accurate case identification by incorporating both clinical diagnoses and treatment histories.

Clinical covariates for this study were derived from data recorded during participants’ first assessment visit, encompassing sociodemographic, lifestyle, and health-related factors. Sociodemographic variables included age, sex, education level, and the specific assessment center attended. Lifestyle factors encompassed smoking status, alcohol consumption frequency, and physical activity levels, while health-related covariates included self-reported overall health status, the presence of long-term illnesses, and body mass index (BMI). By using values recorded at the initial visit, the analysis maintained consistency across participants and minimized potential temporal variability in covariate data. These variables were carefully selected for their relevance to glaucoma risk and their potential to enhance predictive models when integrated with imaging and genetic data. The baseline characteristics of glaucoma cases are summarized in Table 1.

PRS for glaucoma

To calculate glaucoma PRS for 458,316 participants, we employed a ten-fold cross-validation framework to maximize data utilization and minimize overfitting21. GWAS summary statistics for glaucoma were generated for each training set, and PRS for validation sets were computed using the LDpred method with Hapmap3 SNPs from the 1000 genome reference panel22,23. PRS values were standardized within each fold to ensure consistency. Candidate PRS models were tested under different proportions of causal variants, and the final PRS was selected based on the highest AUC performance, ensuring accurate and reliable prediction. We compare our glaucoma PRS scores with the standard glaucoma PRS scores (data field 26265) provided by the UK Biobank24. The standard PRS release includes polygenic scores for glaucoma calculated for all UK Biobank participants using external GWAS training data. By analyzing differences between these scores, we aimed to assess which PRS model more effectively captures genetic risk factors with greater precision and predictive power. PRS for each validation fold was computed using the same LDpred model estimated from the corresponding training folds, ensuring consistent PRS computation within each fold.

OCT image data and IDPs

In the UK Biobank, OCT imaging was performed on approximately 85,000 participants during baseline assessments using the TOPCON 3D OCT-1000 Mk2 device25. This non-invasive imaging technique provides high-resolution, cross-sectional images of the retina, capturing detailed structural information on retinal layers, thickness, and volume. Each OCT scan consists of 128 B-scans (numbered 0 to 127), with each B-scan represented as a grayscale image of 512 × 650 pixels. A standardized imaging protocol ensures uniform data quality, facilitating the downstream analysis of retinal features across the cohort.

From the UK Biobank OCT dataset, a total of 46 IDPs were selected for analysis. These include key retinal measurements such as overall macular thickness, retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) thickness, and ganglion cell-inner plexiform layer (GCIPL) thickness, which are crucial for assessing retinal morphology and health. Each IDP represents a quantitative structural measure of the retina, offering reproducible insights into its condition. Among the 458,316 study participants, individuals with all 42 key IDPs—excluding four with the lowest case proportions (data fields 27851, 27853, 27855, and 27857)—were classified as having imaging data, resulting in a total of 55,469 participants with corresponding OCT images. Supplementary Table 1 provides detailed information on the data fields, descriptions, sample sizes, number of cases, and training AUC values for glaucoma across all 46 IDPs.

All IDPs used in this study were not manually computed but were directly obtained from the UK Biobank as part of the curated OCT-derived phenotypes in Category 100079. These phenotypes were generated using established processing pipelines from previous large-scale OCT studies26,27, which extracted standardized retinal layer measurements and applied UK Biobank–recommended quality control procedures. Following Zhao et al. (2024), we retained IDPs with sample size >30,000 and restricted analyses to scans with an image-quality score >45 (data fields 28552 and 28553), thereby ensuring that all IDPs included were reproducible, quality-controlled imaging traits derived from validated UK Biobank pipelines.

IDS for glaucoma

To compute IDS for glaucoma, we considered a wide range of state-of-the-art architectures, including CNN-based models such as ResNet1816, ResNet5028 and DenseNet12129; Transformer-based models such as Swin Transformer30, ViT31, DeiT32, and XCiT33; and hybrid models such as PiT34 and ConvNeXt35. After careful evaluation, we selected the ConvNeXt architecture, a modern convolutional network that has been progressively updated to align with the design of ViT (Supplementary Figure 1). ConvNeXt integrates key innovations from ViT into a convolutional framework, such as replacing Batch Normalization with Layer Normalization and adopting the Gaussian Error Linear Unit (GELU) activation, which together provide more stable and efficient training. Furthermore, it substitutes standard 3×3 convolutions with large 7×7 depthwise convolutions, thereby expanding the receptive field without compromising computational efficiency. Through these design advancements, ConvNeXt achieves transformer-level performance while retaining the efficiency and inductive biases of traditional CNNs, making it a practical and effective choice for extracting meaningful imaging features to enhance disease risk prediction.

To obtain glaucoma IDS, we applied ConvNeXt to OCT images, generating predictions for each of the 128 B-scans per participant. The dataset was split into five folds for cross-validation to ensure robust model performance and reduce overfitting. The ConvNeXt model was modified by incorporating a dropout layer (rate = 0.4) prior to the linear layer to enhance generalization performance. Training was conducted using the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 0.0001, weight decay of 0.0001, and focal loss (alpha = 3, gamma = 2) to address class imbalance. The learning rate was automatically reduced by a factor of 0.1 when the validation loss did not improve for three consecutive epochs. Predictions from all five folds were combined to generate outputs for the entire dataset. To aggregate predictions across all 128 B-scans per participant, we utilized XGBoost to compute a single representative score, IDS. XGBoost was trained using hyperparameters selected through a grid search, and the final configuration with a learning rate of 0.01, maximum tree depth of 3, and L1 (alpha = 0.1) and L2 (lambda = 0.5) regularization yielded the highest cross-validated AUC. The model ran for 2000 rounds, with early stopping applied after 10 rounds of no improvement. A five-fold cross-validation was performed to ensure robust performance36. For each participant, the ConvNeXt model generated 128 prediction values from the 128 B-scan images, and these values served as the input features to the XGBoost model to produce a single participant-level IDS. All ConvNeXt training was performed on two Intel Xeon Gold 6238R CPUs and a multi-GPU setup consisting of three NVIDIA RTX 4090 and four RTX 3090 GPUs. With this configuration, model training required about 2 minutes per epoch, and the complete five-fold cross-validation process for extracting features from all 128 B-scans was finished in approximately 70 hours.

IGSs estimation based on GWAS for IDPs

IGSs are genetic scores for IDPs designed to assess organ health and disease risk using imaging data. Notably, IGSs can predict health status and genetic disease risk even in the absence of imaging data, making them particularly valuable for large-scale studies or settings with limited imaging resources. To compute IGSs, we utilized 46 IDPs from 55,469 participants to predict genetic scores for an additional 402,847 participants who lacked IDP data. First, we computed GWAS summary statistics for each IDP and then used these data to estimate genetic scores via LDpred, incorporating only HapMap3 SNPs. The fraction of causal variants was optimized to enhance predictive accuracy. By leveraging multiple IDPs, this approach extended IDP-derived genetic associations to a broader population, enabling robust genetic score predictions even without direct imaging data.

To evaluate the predictive accuracy of the estimated IGS values, we divided participants into three groups based on their IGS scores: the lowest 10%, the highest 10%, and the middle 80%. For the glaucoma trait, a chi-squared test was conducted to examine the association between disease status (case vs. control) and the three IGS-based groups (lowest 10%, middle 80%, and highest 10%).

Multimodal approach

We developed a multimodal framework to enhance glaucoma prediction by integrating PRS, IDS, IDPs, IGSs, and clinical covariates (i.e. age, sex, alcohol, smoke, illness, education, ethnic group and center). Age was treated as a continuous variable, and all other clinical covariates were included as categorical inputs. Each data modality underwent independent preprocessing and feature extraction, generating feature vectors used to train an XGBoost model. XGBoost was chosen for its robustness in handling high-dimensional and heterogeneous data. The training process included hyperparameter tuning and cross-validation to optimize performance and prevent overfitting. To evaluate the added value of multimodal integration, we trained baseline models such as logistic regression and lasso regression on individual modalities and compared their performance with the integrated model. By leveraging the complementary strengths of genetic, imaging and clinical data, this framework maximizes predictive accuracy. Additionally, by addressing the challenges of integrating diverse data sources, our approach provides a systematic and scalable methodology for disease prediction.

Results

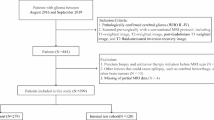

Overview of the study

Figure 1 illustrates the study framework, which presents a multimodal approach for glaucoma classification by integrating genetic, imaging-derived, and clinical data to enhance disease risk prediction. PRS is computed from genetic data using LDpred, while clinical covariates such as age, sex, smoking status, and medical history are incorporated. For individuals with OCT imaging data, IDPs are extracted and processed using ConvNeXt to generate IDS. For individuals without OCT imaging data, IGSs are generated using genetic predictors of IDPs, allowing the use of imaging-related information even when direct imaging is unavailable. All features, including PRS, IDS, IDPs, IGSs, and clinical covariates, are integrated into XGBoost for glaucoma classification, providing a flexible and comprehensive strategy for disease risk prediction.

Multimodal framework for glaucoma classification integrating genetic, imaging-derived, and clinical data. (a) For individuals with OCT imaging data, IDPs are extracted from OCT B-scan images and processed using a ConvNeXt model to generate IDS. PRS is computed from genetic data using LDpred-adjusted SNP effect sizes derived from glaucoma GWAS, and clinical covariates are incorporated. All modalities (IDS, PRS, IDPs, and clinical variables) are integrated using XGBoost to predict glaucoma status. (b) For individuals without OCT imaging data, IDPs from participants with OCT scans are used as phenotypes in GWAS; the resulting summary statistics are processed through LDpred to obtain LD-adjusted SNP effect sizes. These effects are then applied to genotype data from individuals without imaging to compute IGSs, providing genetic proxies for imaging-derived traits. Together with PRS and clinical covariates, these IGSs are used as inputs to XGBoost for glaucoma classification.

Prediction accuracy for glaucoma PRS

We computed glaucoma PRS for 458,316 participants using LDpred with HapMap3 SNPs and ten-fold cross-validation, based on GWAS summary statistics for glaucoma. To evaluate its performance, we compared our internally developed PRS with the standard PRS provided by the UK Biobank, which is derived from external GWAS data. Our internally developed PRS achieved an AUC of 0.6307, while the standard PRS attained a slightly higher AUC of 0.6513. Although our approach resulted in a marginally lower AUC, it reduces overfitting by partitioning the data and maximizing overall data utilization. This method also enhances internal validation, leading to a more reliable PRS evaluation. As shown in the scatter plot in Supplementary Figure 2, the correlation between the two PRS scores is 0.367, indicating moderate similarity. This suggests that both methods provide comparable estimates of genetic risk.

Prediction accuracy for glaucoma IDS

We applied ConvNeXt models to OCT images and generated glaucoma predictions for each of the 128 B-scans using five-fold cross-validation. To evaluate the predictive performance of individual B-scans, we computed the AUC for each B-scan separately. The AUC values ranged from 0.7250 (B-scan #52) to 0.7552 (B-scan #114), indicating moderate discriminatory ability at the single B-scan level (Supplementary Table 2). Most B-scans exhibited AUC values between 0.72 and 0.76, with a median AUC of approximately 0.74. Figure 2(a) presents a bar plot of these AUC values, illustrating the overall trend in individual B-scan performance. While these results confirm that single B-scan predictions contain meaningful predictive information, they also highlight the need to aggregate multiple B-scan predictions to improve robustness. This is further demonstrated in the next step, where we integrate these features using XGBoost to generate a more comprehensive predictive score, IDS.

Prediction accuracy for individual B-scan predictions, IDPs, and IGSs. (a) Bar plot of AUC values for individual B-scan predictions for glaucoma. (b) Bar plot of AUC values and heritability estimates for all IDPs. (c) Bar plot of AUC values for all IGSs, with -log10(p-values) from chi-squared tests evaluating associations between IGS groups and disease status.

Predictive performance of IGSs across OCT-Based IDPs

We evaluated the predictive performance of IGSs across 46 OCT-based IDPs. Heritability estimates for each IDP were computed using HapMap3 SNPs, with values ranging from 0.0046 to 0.3272 (Supplementary Table 3). These findings suggest a moderate genetic component for most IDPs, with certain IDPs (e.g., data fields 27851, 27853, 27855, and 27857) exhibiting relatively high heritability (>0.25). Figure 2(b) presents the heritability estimates and prediction accuracy for all IDPs. For each IDP, we computed an IGS for individuals without OCT images, who lacked IDP data, using GWAS summary statistics for IDPs via LDpred. We then assessed its discriminative ability using AUC, which ranged from 0.4976 to 0.5478, indicating that most IGSs had limited predictive performance when considered individually. To further evaluate the utility of individual IGSs, participants were grouped based on their IGS values, and chi-squared tests were conducted to examine associations with disease status (Supplementary Table 4). Among the 46 IGSs analyzed, 16 showed statistically significant p-values, suggesting a meaningful association with disease status. The prediction accuracy for all IGSs and the p-values from chi-squared tests are presented in Figure 2(c).

Predictive performance for glaucoma in individuals with OCT images

The prediction accuracy of various models, including PRS, IDS, IDPs, IGSs, and clinical covariates, for individuals with OCT images (N=55,469) is presented in the upper row of Table 2. The results evaluate both individual predictors and multimodal approaches that integrate multiple predictors using logistic regression, lasso regression, and XGBoost for individuals with imaging data.

Among single predictors, IDS consistently achieved the highest AUC across all methods. In XGBoost, IDS attained an AUC of 0.7742, outperforming PRS (0.6150), IDPs (0.7106), IGSs (0.6387), and clinical covariates (0.6778). Similarly, in logistic regression and lasso, IDS maintained the highest AUC, surpassing PRS, IDPs, IGSs, and clinical covariates. IDPs, which are closely related to image data, demonstrated stronger predictive performance than PRS and clinical covariates. Replacing IDPs with IGSs resulted in a slight reduction in performance but retained reasonable predictive power, suggesting that IGSs effectively capture part of the information provided by IDPs. Figure 3(a) illustrates the prediction accuracy of single predictors for glaucoma using XGBoost, with AUC values displayed in ascending order. Supplementary Figures 3(a) and 4(a) provide analogous comparisons for logistic regression and lasso, respectively.

Prediction accuracy of single predictors and multimodal approaches for glaucoma using XGBoost, with AUC values displayed in ascending order. (a) Bar plot of AUC values for single predictors, including PRS, IDS, IDPs, IGSs, and clinical covariates, in individuals with OCT images (N=55,469). (b) Bar plot of AUC values for multimodal approaches, including PRS + IDS, PRS + IGSs, PRS + IGSs + clinical covariates, and PRS + IDS + IDPs + clinical covariates, in individuals with OCT images (N=55,469). (c) Bar plot of AUC values for single predictors and multimodal approaches, including PRS, IGSs, and clinical covariates, in individuals without imaging data (N=402,847). Error bars represent the standard errors (SE) of the AUC estimates.

Multimodal approaches significantly improved predictive performance. The combination of all predictors (PRS + IDS + IDPs + clinical covariates) achieved the highest AUC in XGBoost (0.7921), outperforming other combinations such as PRS + IDS (0.7881), PRS + IGSs (0.6733), and PRS + IGSs + clinical covariates (0.7397). This highlights the benefits of integrating multiple features. While logistic regression and lasso also demonstrated improved performance with multimodal approaches, the performance gains were smaller compared to XGBoost. To assess potential redundancy between IDS and IDPs, we calculated pairwise correlations and found that values ranged from –0.26 to 0.10, with none exceeding 0.3. This indicates weak associations and minimal overlap. Moreover, in multimodal models, redundancy was further reduced by regularized methods such as XGBoost and lasso regression, which penalize and down-weight overlapping features. Figure 3(b) presents the prediction accuracy of different predictor combinations using XGBoost, with AUC values displayed in ascending order. For a comprehensive evaluation, Supplementary Figures 3(b), and 4(b) provide corresponding comparisons for logistic regression and lasso, respectively.

Predictive performance for glaucoma in individuals without OCT images

The prediction accuracy of various models, including PRS, IGSs, and clinical covariates, for individuals without OCT images (N=402,847) is summarized in the lower row of Table 2. The results evaluate both individual predictors and multimodal approaches that integrate multiple predictors using logistic regression, lasso regression, and XGBoost. In XGBoost, IGSs achieved an AUC of 0.5467, while PRS (0.6301) and clinical covariates (0.6979) demonstrated higher predictive performance. Logistic regression and lasso produced similar results. Adding IGSs to PRS alone resulted in a slight increase in AUC across all models. In XGBoost, the AUC increased from 0.6301 to 0.6340. When PRS, IGSs and clinical covariates were combined, the multimodal approach further improved performance across all models, achieving an AUC of 0.7397 in XGBoost. Figure 3(c) illustrates the prediction accuracy of different predictor combinations using XGBoost for participants without image data, with AUC values displayed in ascending order to highlight the impact of integrating multiple predictors. Supplementary Figures 3(c) and 4(c) provide analogous comparisons for logistic regression and lasso, reinforcing the trends observed in XGBoost. These results demonstrate that even in the absence of image data, incorporating multiple predictors, including IGSs, can enhance predictive performance.

Comparative evaluation of deep learning architectures for IDS

To assess the impact of different deep learning models on IDS generation, we systematically compared a range of deep learning architectures, including ResNet18, ViT, DeiT, XCiT, PiT, and ConvNeXt. Table 3 summarizes the predictive performance of these models when used as single predictors or integrated into multimodal approaches with PRS, IDPs, and clinical covariates. Across logistic regression, lasso regression, and XGBoost, ConvNeXt consistently achieved the highest AUC values, outperforming both CNN- and Transformer-based alternatives. These results highlight ConvNeXt as the most effective architecture for capturing imaging-derived features and justify its use in the main analyses presented in Table 2. Building on these comparisons, Figure 4 presents the performance of different IDS models using XGBoost. When evaluated as single predictors, ConvNeXt-based IDS provided superior discriminative ability compared with ResNet18, ViT, XCiT, PiT, and DeiT. Moreover, when combined with PRS, or further integrated with IDPs and clinical covariates, ConvNeXt continued to yield the highest AUC values. These findings reinforce the robustness of ConvNeXt in both single and multimodal prediction settings. Supplementary Figures 5 and 6 present results using logistic and lasso regression, showing patterns similar to those observed with XGBoost.

Prediction accuracy of individual deep learning-based IDS and multimodal approaches for glaucoma using XGBoost, with AUC values shown in ascending order. IDS were extracted with ResNet18, ViT, DeiT, XCiT, PiT, and ConvNeXt models. (a) Bar plot of AUC values for IDS extracted using ResNet18, ViT, DeiT, XCiT, PiT, and ConvNeXt in individuals with OCT images (N = 55,469). (b) Bar plot of AUC values for multimodal approaches combining PRS and IDS in individuals with OCT images (N = 55,469). (c) Bar plot of AUC values for multimodal approaches integrating PRS, IDS, IDPs, and clinical covariates in individuals with OCT images (N = 55,469). Error bars represent the standard errors (SE) of the AUC estimates.

Evaluation of model calibration using brier score

To assess model calibration, we additionally computed Brier scores. Supplementary Table 5 shows that ConvNeXt-based IDS achieved lower Brier scores than other single predictors, and multimodal combinations further reduced error, consistent with the AUC-based results in Table 2. Supplementary Table 6 compares different deep learning models for IDS and demonstrates that ConvNeXt consistently produced the lowest Brier scores, confirming its superior performance. Supplementary Figures 7 and 8 further illustrate these findings, demonstrating that ConvNeXt-based IDS provided the most accurate and well-calibrated predictions in both single and multimodal settings. These findings confirm that the main conclusions drawn from AUC analyses are robust when evaluated with Brier score.

SHAP-based interpretation of the multimodal models

To improve interpretability of the XGBoost-based prediction model, we performed SHAP (Shapley additive explanations) analysis on the fully integrated multimodal model for both individuals with and without OCT images. SHAP provides an additive decomposition of the model prediction, and global feature importance was quantified using mean absolute SHAP values. Because each modality contains multiple variables (e.g., clinical covariates and multiple IDPs), we summarized modality-level influence by aggregating SHAP values within each modality and normalizing them so that the modality-level contributions sum to one. For individuals with OCT images (N = 55,469), IDS exhibited the largest contribution to the multimodal model (47.1%), followed by clinical covariates (21.9%), PRS (16.1%), and IDPs (14.9%). For individuals without OCT images (N = 402,847), clinical covariates contributed most strongly (66.50%), followed by PRS (21.95%) and IGSs (11.55%). These results confirm that IDS is the dominant contributor for individuals with imaging data and demonstrate that SHAP provides a clear and interpretable assessment of relative modality-level contributions across the multimodal prediction models.

Discussion

This study evaluated the effectiveness of a multimodal approach that integrates PRS, IDS, IDPs, and clinical factors for glaucoma prediction, leveraging imaging data to enhance predictive accuracy. Additionally, it examined the potential of IGSs as an alternative predictive tool for cases where imaging data is unavailable. By combining genetic, imaging-derived, and clinical data, this approach aimed to improve risk stratification and address challenges posed by missing data. The study also explored the comparative utility of different predictive models, demonstrating how integrating multiple data sources can refine disease risk assessment and provide a more robust prediction framework.

Among participants with imaging data, IDS emerged as the strongest predictor, achieving the highest classification performance in XGBoost. In contrast, IDPs and PRS demonstrated lower predictive power individually. However, when all predictors were combined, the model achieved its highest performance, highlighting the value of integrating diverse data sources to improve accuracy. The superior performance of IDS over IDPs suggests that deep learning-derived features capture structural variations in a more nuanced manner than traditional imaging phenotypes. Specifically, IDPs are constrained to a small set of predefined structural measurements, which may overlook subtle or complex patterns of retinal change. In contrast, IDS leverages data-driven feature extraction from the entire OCT image, allowing the capture of microstructural variations, layer-specific texture changes, and nonlinear spatial relationships across the retina. These features may reflect early pathological alterations that extend beyond conventional IDP metrics such as thickness or volume, thereby providing a more comprehensive representation of glaucomatous damage. While IDPs are predefined based on expert knowledge, IDS leverages data-driven feature extraction, enabling it to detect subtle patterns linked to disease progression that may not be explicitly measured by conventional imaging biomarkers. This finding underscores the growing role of deep learning in medical imaging, particularly in the development of predictive models that extend beyond manually curated features.

Among participants without imaging data, this study highlights the potential of IGSs as substitutes for IDPs. Since IGSs are derived using both genetic and imaging information, they encode structural characteristics in a way that can be applied even in the absence of direct imaging data. This property makes IGSs functionally similar to PRS, as they can be computed solely from genetic data. However, their limited standalone performance suggests that while IGSs capture some structural information, they do not fully replicate the depth of detail provided by IDPs. Nonetheless, their ability to enhance PRS-based predictions indicates that incorporating imaging-derived genetic markers could be beneficial, particularly in datasets where traditional imaging phenotypes are inaccessible.

When comparing our results with prior multimodal glaucoma studies, it is important to note that many of those analyses were conducted on smaller case-control samples and often reported very high AUC values (≥0.90)37,38. However, these estimates are likely inflated due to limited sample size and the use of balanced case-control ratios. In contrast, our study utilized a large-scale UK Biobank cohort, including 55,469 individuals with OCT images and 402,847 without imaging, and applied strict cross-validation procedures. These design features likely yield more conservative but robust and generalizable AUC estimates (~0.79), highlighting the scalability and robustness of our multimodal framework. Direct head-to-head comparison with prior studies is therefore not feasible, but our findings remain broadly consistent with, and in some respects more reliable than, previously reported multimodal approaches.

This study has several limitations. First, IDS, derived from deep learning models, demonstrated limited performance in logistic regression and lasso models. This limitation may be attributed to the high-dimensional and non-normal characteristics of IDS data, making it less suitable for methods that assume linearity or normality. Second, while IGSs showed some promise as partial substitutes for IDPs among participants with imaging data, their predictive performance remained inferior to that of IDPs. Additionally, IGSs exhibited poor predictive power when used alone in the larger dataset without imaging data, and their marginal contribution when combined with PRS further underscores their limitations as complete replacements for IDPs. Third, although various deep learning models were considered, IDS was ultimately computed using ConvNeXt, a modern CNN that incorporates key innovations from ViT to achieve stable and efficient feature extraction. While ConvNeXt provided a practical and effective choice, further evaluation with other advanced architectures will be necessary to ensure optimal performance across diverse settings. Fourth, the generalizability of our findings may be limited, as the study relied on UK Biobank data, which consists primarily of individuals of European ancestry and may not fully represent other populations. This limitation highlights the need for external validation in cohorts of more diverse ancestries to ensure broader applicability of our results. Fifth, the study exclusively used B-scan data from OCT images, omitting other structural information such as optic disc and macula characteristics, as well as complementary imaging modalities such as fundus photography. The exclusion of these data may have restricted the predictive performance of our models, and future studies should aim to integrate a wider range of imaging modalities.

To address these limitations, future research will focus on several key areas. First, integrating fundus imaging alongside OCT B-scan data will be explored to leverage a broader range of structural information and enhance predictive performance. Second, while this study employed single 2D models, future efforts will compare and implement advanced 2D and 3D models. Notably, 3D models have the potential to incorporate spatial information from OCT data, which may further improve glaucoma prediction. Third, to enhance generalizability, future studies will train models on datasets beyond the UK Biobank, incorporating OCT data from diverse populations and applying these models to UK Biobank to assess external validity. In addition, future work will extend the model to non-European populations to evaluate cross-ancestry generalizability. Large-scale cohorts such as Biobank Japan and the Taiwan Biobank offer promising opportunities for external validation, either by computing IGSs using their genetic data or, where available, by training deep learning models on cohort-specific ocular imaging. Such collaborations will enable a more comprehensive assessment of model performance across diverse ancestral groups. Fourth, IDS will be computed using a variety of alternative deep learning architectures—including deeper CNNs, Transformer-based models, and hybrid networks—to evaluate the influence of model selection on prediction performance. Fifth, while IGSs were derived from IDPs in the current study, future work will explore the feasibility of constructing IGSs using IDS features from various deep learning models. This may allow IGSs to capture more complex imaging-derived information, extending their utility in settings without direct access to imaging data. Lastly, to improve the predictive performance of IGSs, further research will explore the integration of additional genetic and environmental data or the development of novel computational methodologies to enhance their utility as surrogate variables. In addition, although the predictive performance of IGSs was modest when used alone, they may provide practical value in resource-limited settings where OCT imaging is unavailable. Their utility is enhanced when combined with PRS and clinical covariates, and future work will focus on improving IGSs by deriving them from IDS features and integrating additional genetic and environmental information.

This study highlights the value of a multimodal approach in improving the predictive accuracy of glaucoma risk. While IDS and IGSs demonstrated potential in specific contexts, their limitations emphasize the need for further research to refine these predictors and enhance their applicability. This work provides a foundation for future studies to advance multimodal methodologies and develop innovative strategies for more effective glaucoma prediction.

Data availability

All data and code are available at https://github.com/khm1576/Multimodal for academic use. Additional data can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Reference

Lewis, C. M. & Vassos, E. Polygenic risk scores: from research tools to clinical instruments. Genome Med. 12, 44 (2020).

Torkamani, A., Wineinger, N. E. & Topol, E. J. The personal and clinical utility of polygenic risk scores. Nat. Rev. Genet. 19, 581–590 (2018).

Rietveld, C. A. et al. Replicability and robustness of genome-wide-association studies for behavioral traits. Psychol. Sci. 25, 1975–1986 (2014).

Choi, S. W., Mak, T.S.-H. & O’Reilly, P. F. Tutorial: a guide to performing polygenic risk score analyses. Nat. Protoc. 15, 2759–2772 (2020).

Wray, N. R., Goddard, M. E. & Visscher, P. M. Prediction of individual genetic risk to disease from genome-wide association studies. Genome Res. 17, 1520–1528 (2007).

Visscher Peter, M. et al. Common polygenic variation contributes to risk of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Nature 460, 748–752 (2009).

Kullo, I. J. et al. Polygenic scores in biomedical research. Nat. Rev. Genet. 23, 524–532 (2022).

Chatterjee, N., Shi, J. & García-Closas, M. Developing and evaluating polygenic risk prediction models for stratified disease prevention. Nat. Rev. Genet. 17, 392–406 (2016).

Chung, W. et al. Efficient cross-trait penalized regression increases prediction accuracy in large cohorts using secondary phenotypes. Nat. Commun. 10, 569 (2019).

Chung, W. Statistical models and computational tools for predicting complex traits and diseases. Genom. Inform. 19, e36 (2021).

Foley, S. F. et al. Multimodal brain imaging reveals structural differences in Alzheimer’s disease polygenic risk carriers: a study in healthy young adults. Biol. Psychiatry. 81, 154–161 (2017).

Scelsi, M. A. et al. Genetic study of multimodal imaging Alzheimer’s disease progression score implicates novel loci. Brain 141, 2167–2180 (2018).

Mehta, P. et al. Automated detection of glaucoma with interpretable machine learning using clinical data and multimodal retinal images. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 231, 154–169 (2021).

Kanyal, A. et al. Multi-modal deep learning from imaging genomic data for schizophrenia classification. Front. Psychiatr. 15, 1384842 (2024).

Venugopalan, J., Tong, L., Hassanzadeh, H. R. & Wang, M. D. Multimodal deep learning models for early detection of Alzheimer’s disease stage. Sci. Rep. 11, 3254 (2021).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proc. of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition 770-778 (2016).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Identity mappings in deep residual networks. In Computer Vision–ECCV 2016: 14th European Conference Amsterdam The Netherlands October 11–14 Proc., Part IV 14 630-645 (Springer, 2016).

Iandola, F. Densenet: Implementing efficient convnet descriptor pyramids. arXiv preprint arXiv:1404.1869 (2014).

Yang, X. et al. Multi-organ imaging-derived polygenic indexes for brain and body health. medRxiv, 2023.04. 18.23288769 (2023).

Allen, N. E., Sudlow, C., Peakman, T. & Collins, R. UK biobank data: come and get it. Sci. Transl. Med. 6, 224ed4 (2014).

Lee, A. et al. Type 2 diabetes and its genetic susceptibility are associated with increased severity and mortality of COVID-19 in UK Biobank. Commun. Biol. 7, 122 (2024).

Loh, P.-R. et al. Efficient Bayesian mixed-model analysis increases association power in large cohorts. Nat. Genet. 47, 284 (2015).

Vilhjálmsson, B. J. et al. Modeling linkage disequilibrium increases accuracy of polygenic risk scores. Am. J.Hum. Genet. 97, 576–592 (2015).

Thompson, D. J. et al. A systematic evaluation of the performance and properties of the UK Biobank Polygenic Risk Score (PRS) Release. Plos one 19, e0307270 (2024).

Han, X. et al. Automated AI labeling of optic nerve head enables insights into cross-ancestry glaucoma risk and genetic discovery in> 280,000 images from UKB and CLSA. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 108, 1204–1216 (2021).

Zhao, B. et al. Eye-brain connections revealed by multimodal retinal and brain imaging genetics. Nat. Commun. 15, 6064 (2024).

Yang, X. et al. Multi-organ imaging-derived polygenic indexes for brain and body health. medRxiv, 2023.04. 18.23288769 (2024).

Hu, J., Shen, L. & Sun, G. Squeeze-and-excitation networks. In Proc. of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition 7132-7141 (2018).

Huang, G., Liu, Z., Van Der Maaten, L. & Weinberger, K.Q. Densely connected convolutional networks. In Proc. of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition 4700-4708 (2017).

Liu, Z. et al. Swin transformer: Hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In Proc. of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision 10012-10022 (2021).

Dosovitskiy, A. et al. An image is worth 16x16 words: transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.11929 (2020).

Touvron, H. et al. Training data-efficient image transformers & distillation through attention. In International conference on machine learning 10347-10357 (PMLR, 2021).

Ali, A. et al. Xcit: Cross-covariance image transformers. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 34, 20014–20027 (2021).

Wang, W. et al. Pyramid vision transformer: A versatile backbone for dense prediction without convolutions. In Proc. of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision 568-578 (2021).

Liu, Z. et al. A convnet for the 2020s. In Proc. of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition 11976-11986 (2022).

Chen, T. & Guestrin, C. Xgboost: A scalable tree boosting system. In Proc. of the 22nd acm sigkdd international conference on knowledge discovery and data mining 785-794 (2016).

Huang, X. et al. Detecting glaucoma from multi-modal data using probabilistic deep learning. Front. Med. 9, 923096 (2022).

Xiong, J. et al. Multimodal machine learning using visual fields and peripapillary circular OCT scans in detection of glaucomatous optic neuropathy. Ophthalmology 129, 171–180 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the individuals who participated in the study. This research has been conducted using the UK Biobank Resource (application number 77890).

Funding

This work was supported by the Soongsil University Research Fund (New Professor Support Research) of 2020.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.C. and H.K. conceived and designed the experiments. H.K. and G.L. performed the experiments and analyzed the data, as well as generated the necessary materials and analysis tools. H.K. and W.C. primarily wrote and reviewed the manuscript, and H.K., G.L., and W.C. contributed to its revision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The UK Biobank has received approval from the North West Multi-centre Research Ethics Committee (MREC) as a Research Tissue Bank (RTB), allowing researchers to conduct studies within the RTB framework without requiring separate ethical approval. At recruitment, participants provided informed consent for research use, and all data were fully anonymized before access to ensure participant confidentiality. For this retrospective analysis, the requirement for additional informed consent was waived by the North West Multi-centre Research Ethics Committee (MREC).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, H., Lee, G. & Chung, W. Multimodal deep learning approaches for improving polygenic risk scores with imaging data. Sci Rep 16, 4012 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34153-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34153-6