Abstract

This study proposes a novel external steel-frame system equipped with viscoelastic nodal dampers for improving the seismic performance of reinforced concrete (RC) structures. The nodal dampers utilize viscoelastic materials to dissipate seismic energy through hysteretic shear deformation, thereby reducing the dynamic response of the main structure. An external steel frame is connected to the original RC frame through these dampers, forming an integrated load-bearing and energy-dissipating system. A series of shaking table tests were conducted on two models: the original RC frame and the retrofitted structure incorporating the external steel frame with viscoelastic nodal dampers. The tests investigated the acceleration and displacement responses under different seismic excitations, with peak ground accelerations ranging from 0.2 g to 1.0 g. The results demonstrate that the proposed system significantly enhances stiffness and energy dissipation capacity, effectively reducing floor acceleration and inter-story drift. Under moderate earthquakes, the external steel frame increases the overall stiffness, while under strong ground motion, the viscoelastic nodal dampers dominate energy dissipation. The maximum reduction in acceleration response reached 64%, and inter-story displacement was reduced by up to 52.4%. These findings confirm the system’s ability to provide both seismic strengthening and damping, offering a practical and sustainable solution for the seismic retrofit of existing RC structures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The protection of buildings against natural disasters, particularly earthquakes, has become a major focus of modern civil and structural engineering. This issue is especially critical in regions frequently exposed to moderate-to-severe seismic events, where both the safety of occupants and economic stability are at risk. Many existing buildings still fail to meet current seismic design requirements, underscoring the urgent need for more effective and sustainable reinforcement strategies. Traditional seismic strengthening techniques-such as local structural modifications, section enlargement, or the addition of external steel reinforcement can improve load-bearing capacity but often entail high costs, architectural disruption, and alterations to the original structural system1. Moreover, these conventional methods primarily rely on enhancing the inherent strength and stiffness of the structure, which may be insufficient to withstand extreme seismic excitations.

In contrast, energy-dissipation and damping technologies provide an efficient means of mitigating earthquake-induced damage by transforming mechanical energy into heat through the controlled deformation of damping components2,3,4. These systems reduce structural responses and limit damage propagation without extensive modification of the main load-bearing members. During severe earthquakes, damping devices dissipate energy through hysteretic shear deformation, enabling better control of lateral displacements and internal forces5,6,7,8. From a sustainability perspective, energy-dissipating and shock-absorbing systems offer economic and environmental advantages compared with traditional reinforcement, aligning with the concept of organic renewal—that is, extending the service life of existing buildings while maintaining functionality and minimizing material consumption. Consequently, energy-dissipating damping systems have become a vital branch of earthquake engineering, widely applied to bridges, tall buildings, and long-span structures. By incorporating replaceable damping elements, these systems enhance structural resilience, improve damping ratios, and reduce the risk of catastrophic failure under strong ground motion.

In the field of passive damping control, extensive research has been conducted on various types of damping and energy dissipation systems to improve the seismic resilience of structures. Han et al.9 introduced the concept of Tuned Liquid Column Dampers (TLCDs) for flexible structures and demonstrated their effectiveness in mitigating random seismic excitations through post-earthquake analyses. Similarly, Zhang et al.4 investigated the behavior of viscoelastic dampers in frame structures, analyzing the influence of damper support conditions and material parameters on structural damping ratios. Their work emphasized the importance of controlling the relaxation time coefficient and proposed a calculation method for evaluating seismic responses with viscoelastic damping. These studies confirmed that appropriately designed viscoelastic dampers could effectively reduce inter-story displacement and structural damage10,11,12,13,14.

Since the early introduction of vibration control concepts by J.T. Ryao15, various energy dissipation mechanisms have been explored and refined. Huckelbridge et al.16 showed that adding rocking walls can significantly reduce strength demands in buildings, while Yim et al.17 revealed that structural mass, damping ratio, and aspect ratio strongly influence rocking behavior. Ri-Hui Zhang18 examined the influence of temperature on viscoelastic damper performance and proposed optimal placement strategies for cost-effective mitigation. Numerical and experimental studies by Tezcan19 and INAI Eiichi20 validated the Maxwell and Voigt models, confirming that viscoelastic materials exhibit stable hysteretic characteristics under cyclic loading. Other studies have proposed diverse forms of metallic and friction dampers, such as displacement-type dampers for masonry structures21, honeycomb steel dampers22, and optimized metal damper layouts for cost-effective energy dissipation23. In recent years, researchers have extended damping concepts to semi-active and hybrid control systems. Peng24 optimized the parameters of magnetorheological (MR) dampers for reliable real-time control, while Yang Hai-xu et al.25 evaluated a nonlinear energy sink (NES) applied to reinforced concrete (RC) frames, showing remarkable energy dissipation capacity during strong earthquakes. Maida et al.26 investigated friction damper–RC frame interactions through finite element analysis, demonstrating that the diameter of deformed steel bars passing through the concrete significantly affects energy dissipation performance. Likewise, Reza Siami Kaleybar et al.27 compared different passive control systems in an eight-story steel frame and found that friction dampers produced the greatest reduction in structural response. He et al.28 experimentally verified that viscous dampers can substantially enhance the dynamic load capacity of precast concrete frames under cyclic loading.

Although these studies have significantly advanced the understanding of passive damping systems, several limitations remain. Most research has concentrated on internal or brace-type dampers, which are often difficult to install in existing buildings due to space and construction constraints. Furthermore, the interaction between external steel frames and joint-based (nodal) dampers-which can provide modular, replaceable, and externally attached energy dissipation-has rarely been investigated experimentally. Existing studies on viscoelastic materials have demonstrated their excellent damping potential, yet experimental validation in hybrid external frame systems remains scarce. Therefore, further research is needed to explore integrated external steel-frame structures equipped with viscoelastic nodal dampers, which can effectively combine stiffness enhancement and energy dissipation while maintaining construction simplicity and replaceability.

To address these gaps, this paper proposes a novel external steel-frame system equipped with viscoelastic nodal dampers29. This system dissipates seismic energy through hysteretic shear deformation of viscoelastic components, effectively protecting the main structure from excessive damage. In this configuration, the nodal dampers are installed at the joints between the external steel subframe and the original reinforced concrete (RC) frame, forming an integrated system that combines stiffness enhancement with energy dissipation capability. The external frame can be attached with minimal disturbance to building operations and can be coordinated with façade renewal projects. The modular design of the nodal dampers allows easy installation, maintenance, and post-earthquake replacement, aligning with sustainable and resilient construction principles. To evaluate its performance, shaking table tests were conducted on two models: the original RC frame and the retrofitted frame incorporating the external steel frame with viscoelastic nodal dampers. Under peak ground accelerations ranging from 0.2 g to 1.0 g, the tests compared acceleration, displacement, inter-story drift, and energy dissipation responses. The findings demonstrate that the proposed system effectively improves seismic resilience and provides a practical foundation for applying external energy-dissipating systems in structural engineering practice.

Experimental program

Original reinforced concrete frame structure

The experimental reinforced concrete structure is a four-story frame, symmetrically designed in both the X and Y axes, with a total height of 2525 mm. The rigid base measures 300 mm, making the actual model height 2225 mm. The model includes column sections measuring 62.5 mm×62.5 mm and a 40 mm thick floor slab. As the shaking table’s vibration and seismic wave input align with the X-axis, the external frame of the new structure is aligned accordingly. The construction process of the model involved steel bar arrangement and binding, formwork assembly, concrete pouring, and subsequent curing. Seismic reinforcement technology typically involves making partial modifications to existing structures. Despite meeting post-reinforcement requirements, implementing this concept can be costly and challenging due to objective factors. A damper is installed within the reinforced concrete structure using a steel frame, based on the node energy dissipation concept. The shear hysteretic performance of this shock-absorbing device reduces the structure’s self-consumed energy, improving its overall energy dissipation capacity and seismic performance.

Establishment of new external frame structure

The shaking table model was designed following the similitude principles specified in JGJ/T 101–201530, adopting a geometric similarity ratio of 1:8 between the model and the prototype to ensure comparable dynamic characteristics. The quality and reliability of the model were verified through strict model testing. The total mass of the model was determined by scaling the prototype’s total weight using the self-weight similarity coefficient. However, due to the differences in material properties between the model and the prototype, the resulting mass did not fully satisfy the required similitude conditions. Consequently, when subjected to seismic excitations scaled by the corresponding similarity coefficients, the input seismic energy of the model did not match that of the prototype under equivalent dynamic conditions. To address this discrepancy, supplementary counterweights were added to the structural model to meet the similitude-based mass requirements. The total mass of the superstructure was adjusted to 1.8 tonnes. Based on the measured compressive strength of the model concrete, the stress similarity coefficients were recalculated, and the final mass distribution and counterweights for each floor were determined, as summarized in Table 1.

Four operational conditions are outlined for the installation of nodal dampers in a building. The first condition involves placing nodal dampers on the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th floors at symmetrical positions. The second condition includes nodal dampers on the 3rd and 4th floors. The third condition specifies a node damper at a symmetrical position on the 4th floor. The fourth condition entails welding a connector at one side of each layer’s node position and securing the damper with a screw. The external steel frame, made of cold-formed square hollow steel measuring 50 mm×50 mm×3 mm, is reinforced with diagonal braces and rigidly connected to the traditional structure. The new structure described in this study incorporates a method of connection that enhances stiffness by distributing nodal dampers symmetrically. It includes 11 acceleration sensors and 11 displacement sensors positioned on steel frames spanning floors 2 to 4, as well as on central columns from floors 1 to 4 in the Y direction. Speed sensors are placed on steel frames across floors 2 to 4, with four additional sensors on central columns of floors 1 to 4 in the Y direction. Removal of the external steel frame results in the structure reverting to a traditional configuration. The fabrication and installation of the attached steel frame are shown in Fig. 1. The number of sensors and signal acquisition system channels is limited, requiring strategic placement of sensors at key positions on the structure to gather comprehensive measurement point data. The sensor arrangement can be visualized in Fig. 2.

Each nodal damper is installed at the joint between the external steel subframe and the original RC frame. The damper is welded to a steel connector on the subframe and anchored to the RC beam-column joint through an embedded steel plate and high-strength bolts, forming a semi-rigid connection capable of transmitting both shear and axial forces. This hybrid anchorage ensures reliable load transfer between the two frames while allowing limited relative displacement for viscoelastic deformation. During the shaking-table tests, no slippage or separation was observed at the interface, confirming that the connection provided sufficient stiffness and integrity to guarantee coordinated motion between the steel and concrete frames.

Input seismic wave and operating conditions

Three seismic waves were selected for the shaking table tests: the El Centro (1940), Taft (1952), and Lanzhou artificial waves, each with a duration of approximately 30 s. Before the seismic excitation, the model structure was subjected to white-noise tests to identify its fundamental dynamic properties. The selected ground motions were applied to both the original reinforced concrete (RC) frame and the composite steel–RC frame equipped with nodal dampers under four seismic intensity levels—frequent 8-degree, rare 7-degree, rare 8-degree, and rare 9-degree earthquakes—with peak ground accelerations ranging from 0.2 g to 1.0 g, as summarized in Table 2. The selection and number of seismic records comply with the Chinese Code for Seismic Design of Buildings (GB 50011 − 201031 and the Code for Seismic Test Methods of Buildings (JGJ/T 101–201530, which recommend using no fewer than three representative ground motions. Accordingly, the El Centro, Taft, and Lanzhou artificial waves were chosen to represent typical far-field, near-field, and artificial design excitations, respectively. Each record was amplitude-scaled to target peak ground accelerations of 0.2 g, 0.4 g, 0.8 g, and 1.0 g corresponding to different seismic intensity levels, while maintaining its original frequency characteristics to ensure consistency of the energy content and waveform features.

Determination of damper parameters

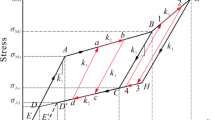

The experiment involved a damper composed of two steel plates with viscoelastic material in between. When an external force is applied, the atoms in the damper’s molecular chain shift from disorder to sliding. Once the force is removed, the molecular chain returns to its original state, releasing the absorbed energy. This process not only dissipates energy but also reduces structural vibration. Three dampers were randomly selected for testing. A jack was mounted horizontally on a reaction frame using angle steel, and the damper was firmly attached to the base. Horizontal displacement of the damper was measured with a push rod displacement sensor. The Donghua dynamic measuring instrument recorded changes in force and displacement during the experiment, as shown in Fig. 3. The cyclic loading test followed a displacement-controlled protocol based on JGJ/T 101–201530, repeated for three cycles at each level. The third cycle, representing the stable hysteretic stage, was used for performance evaluation and is shown in Fig. 4. After simplifying the hysteresis curve into a double-line model, the mechanical parameters of the damper were analyzed and computed, as detailed in Table 3.

The analysis of the damper’s hysteresis curve shows a stable and full loop, demonstrating its efficient energy dissipation even under small displacements. With increasing displacement amplitudes after yielding, the damper exhibits significant strain hardening. Specifically, the post-yield stiffness is 0.143 kN mm−1, the yield force is 2.12 kN, the equivalent stiffness is 0.23 kN mm−1, and the equivalent damping ratio reaches 13.9%, confirming its reliable hysteretic performance and energy dissipation stability.

Experimental phenomena

In In traditional RC structures, pronounced vibrations occur due to insufficient inherent damping, leading to persistent oscillations after excitation. In contrast, the redesigned steel-reinforced system exhibits significantly reduced vibrations, with sharp declines in both displacement and acceleration, and rapid attenuation following excitation. The shear deformation mechanism efficiently transfers seismic energy to the viscoelastic nodal dampers, facilitating effective energy dissipation within the structural framework. During shaking table tests, varying seismic inputs and increasing peak ground accelerations (PGAs) led to progressive crack development in the model. Under three seismic waves with a PGA of 0.4 g (rare intensity-8 earthquake), the structure exhibited visible sloshing and minor vibrations. Post-test inspection revealed fine cracks at the connections between the second-floor beam and right-edge column, and between the third-floor right-edge column and its corresponding beam, as shown in Fig. 5. No significant overall deformation was observed, while white-noise analysis indicated a slight reduction in natural frequency, suggesting minor yielding within the structure.

Subjected to three seismic waves with a peak acceleration of 0.8 g (rated 8 in rarity), the model structure experienced notable vibrations. Although no visible signs of yielding were present, there was initial damage and fragmentation observed. Cracks were identified on the top layer of the structure, along with extensive cracks and fractured concrete debris at the base. As shown in Fig. 6, the existing cracks displayed a tendency to widen.

Subjected to three seismic waves with a peak acceleration of 1.0 g (rated 9 in rarity), existing cracks continued to propagate and deepen. The middle section of the second-tier column exhibited horizontal penetration, as shown in Fig. 7. Substantial detachment occurred between the second-floor beam and the left edge column, with cracks propagating deep into the structure. Cracks at the junction between the second-floor beam and the right-side column of the model structure extended in three directions, accompanied by significant concrete spalling. The steel reinforcement within the model structure was visible, and visual inspection revealed no significant buckling. Despite being predominantly damaged, the model structure still retains its capacity to withstand vertical loads.

Under a 0.2 g seismic excitation, the model structure exhibited no visible deformation, remaining in the elastic stage. As the peak ground acceleration (PGA) increased to 0.4 g, minor cracks appeared, leading to a slight reduction in stiffness. Further increases in acceleration caused these cracks to widen progressively, ultimately resulting in concrete spalling and localized failure. The failure mode was relatively uniform, with cracks distributed across all stories. In comparison, the pure RC frame showed crack concentration mainly at column hinges, while the hybrid structure with external steel frames demonstrated superior seismic performance, despite more visible cracking. The external frames increased global stiffness, redistributing forces and inducing plastic hinges at beam–column joints. Structural regions without external reinforcement experienced lower stress levels and less damage. Even under 1.0 g excitation, the structure retained its vertical load-bearing capacity, with only minor floor cracking, confirming its efficient energy dissipation and enhanced seismic resilience.

Experimental results

Structural acceleration response

Acceleration data from three seismic waves were input into both a pure frame structure model and a steel-concrete frame structure model with nodal dampers. The collected data was then analyzed to compare the time-history curves of the two structures. As shown in Fig. 8, four operational conditions were evaluated in comparison with the pure frame structure: a three-layer arrangement, a double-layer arrangement, a single-layer arrangement, and a unilateral arrangement on each layer. The acceleration curve for the fourth layer of both structures was chosen at a peak acceleration of 0.4 g during the Lanzhou artificial wave, with similar results observed under other seismic waves, as shown in Fig. 9.

The acceleration response of each floor serves as a critical index for assessing the dynamic characteristics of the model structure. The model structure was subjected to three sequential seismic waves: the Taft, EL-Centro, and Lanzhou artificial waves, with peak accelerations ranging from 0.2 g to 1.0 g. Acceleration sensors were strategically placed on each floor. Prior to installation, all sensors were calibrated to ensure the collection of valid data. In light of discussions regarding the optimal arrangement of nodal dampers, four distinct operational conditions were delineated for analysis. The acceleration damping coefficient for each layer is calculated as the difference between the maximum acceleration of each layer in the pure frame and that in the new structure. This difference is then divided by the maximum acceleration of each layer in the pure frame, as delineated in Eq. (1). Specific values are presented in Tables 4, 5, 6 and 7.

where: Ka is the acceleration damping coefficient (%), Ha.i. is the maximum acceleration (m/s2) of each layer of the pure frame structure. Haj is the maximum acceleration value (m/s2) of each floor of the steel-concrete frame structure with additional nodal dampers.

Damping devices are installed on the second, third, and fourth layers. When subjected to identical seismic conditions, the shock absorption capacity of both Taft and El Centro waves improves as the peak acceleration of earthquake waves increases, reaching a maximum effectiveness of 54%. However, this improvement trend eventually diminishes. In contrast, under the same seismic conditions, the artificial wave absorption effect observed in Lanzhou is more significant, resulting in a notable shock absorption effect with an effectiveness of 52%.

The second set of operational conditions involves the connection of the damping device at the third and fourth levels. Under these conditions, as peak acceleration increased due to the same seismic wave, the shock absorption efficacy of the El Centro wave remained consistent, whereas the performance of the Tsft and Lanzhou artificial waves demonstrated a decline. The data indicate that, under the Taft waves, the shock absorption performance at these two levels is optimal, achieving a 66% reduction in vibration.

The damping devices were arranged in a three-tier configuration under the specified working conditions. Under identical seismic excitations, the stability of the three dampers remained around 58% as the peak ground acceleration (PGA) increased. Among the seismic inputs, the Taft wave exhibited the best damping performance, achieving 66% effectiveness at PGAs of 0.2 g and 0.4 g, outperforming the El Centro and Lanzhou artificial waves. At higher PGAs (0.6 g and 1.0 g), the El Centro wave showed improved damping efficiency, reaching a maximum of 63%, indicating the system’s adaptive energy dissipation capability under increasing seismic intensity.

Under Working Condition 4, the damper was installed on one side of the structure. The second floor exhibited the highest damping efficiency under the Taft wave (72%), whereas the first floor achieved maximum damping effectiveness under the El Centro and Lanzhou artificial waves, at 71% and 64%, respectively. As the peak ground acceleration (PGA) increased under different seismic excitations, a progressive decline in damping efficiency was observed for all wave inputs. This reduction is primarily attributed to the development of structural damage and the consequent degradation of the damper’s energy dissipation capacity. A comparative analysis of the acceleration responses between the external steel-frame structure with nodal dampers and the pure RC frame is presented in Fig. 10, illustrating the superior damping performance and vibration control of the proposed system under varying seismic conditions.

Acceleration comparison curve of steel frame structure with external joint damper and pure frame structure. (a) EL Centro peak acceleration 0.2 g curve, (b) EL Centro peak acceleration 0.4 g curve, (c) EL Centro peak acceleration 0.8 g curve, (d) EL Centro peak acceleration 1.0 g curve, (e) Lanzhou artificial wave peak acceleration 0.2 g curve, (f) Lanzhou artificial wave peak acceleration 0.4 g curve, (g) Lanzhou artificial wave peak acceleration 0.8 g curve, (h) Lanzhou artificial wave peak acceleration 1.0 g curve, (i) Taft wave peak acceleration 0.2 g curve, (j) Taft wave peak acceleration 0.4 g curve, (k) Taft wave peak acceleration 0.8 g curve, (l) Taft wave peak acceleration 1.0 g curve.

Analysis of the peak acceleration response and damping effectiveness across each layer of the model structure reveals:

(1) Initially, as peak acceleration increases, so does the damping effect. However, in the fourth working condition, a linear decline in damping effectiveness is observed, indicative of a reduction in the model structure’s stiffness and an increase in damage due to escalating seismic activity, working condition sequence, and other external factors, signaling the transition of the structure into a profound elastic-plastic phase.

(2) Diverse seismic waves impact the damping effectiveness differently: the Taft wave yields superior damping on the second and third floors, peaking at 72%. The El Centro wave demonstrates maximum damping at 71% in the third layer at PGAs of 0.8 g and 1.0 g. Conversely, the Lanzhou artificial wave exhibits the least effectiveness, with a mere 58% damping across the structure.

(3) Examination of the curve reveals that the seismic performance across various working conditions exhibits a trend of improvement relative to that of a pure frame structure. The Taft wave demonstrates the most significant damping effect, most pronounced in the third layer, followed by the second, with the first layer showing the weakest response; conversely, the El Centro wave exhibits a consistent decline in damping effectiveness. Under the Lanzhou artificial wave, particularly at PGAs of 0.2 g and 0.4 g, the fourth layer’s damping effectiveness is minimal and irregular, suggesting potential instrumental inaccuracies during testing.

(4) Under the influence of the Taft and El Centro waves, the model structure’s vibration reduction is notably pronounced, achieving 64%. Damping under condition one is minimal; however, with the Lanzhou artificial wave, damping is most effective in working condition 7 at 45%, followed by condition 8 at 41%, with condition 1 exhibiting the poorest performance. This indicates that increasing the number of dampers does not necessarily enhance performance. Optimal control over the placement and quantity of dampers is crucial for maintaining the structural stiffness without significantly increasing its acceleration, thereby effectively achieving desired outcomes.

Structural displacement response

Four experimental conditions were conducted, and seismic excitation tests using the Taft, El Centro, and Lanzhou artificial waves were performed sequentially. Figure 11 presents the interstory displacement curves for each condition under various peak ground accelerations (PGAs).

Displacement curves under different peak accelerations. (a) EL Centro wave peak inter-layer displacement 0.8 g curve, (b) EL Centro wave peak inter-layer displacement 1.0 g curve, (c) Lanzhou artificial wave peak inter-story displacement 0.8 g curve, (d) Lanzhou artificial wave peak inter-story displacement 1.0 g curve, (e) Taft wave peak inter-layer displacement 0.8 g curve, (f) Taft wave peak inter-layer displacement 1.0 g curve.

The displacement response of the structure during seismic excitation was recorded using a cable displacement sensor. The displacement damping coefficient was defined as the difference between the measured displacements of two adjacent floors, from which the maximum interstory displacement was obtained. The coefficient was calculated by subtracting the displacement of the pure frame from that of each experimental condition, as expressed in Eq. (2). Analysis of the interstory displacement curves shows that, under all three seismic waves, the fourth floor exhibited the most significant damping effect, with a generally positive correlation between damping efficiency and story height. The calculated results are summarized in Tables 8, 9, 10 and 11, where values in brackets denote measured displacements, and those outside represent the corresponding damping coefficients.

where, Ks denotes the displacement damping coefficient (%); Hsi represents the interstory displacement (mm) of the original RC frame; and Hsj refers to the interstory displacement (mm) of the steel–concrete frame equipped with viscoelastic nodal dampers.

Analysis of the curve and table data on interlayer displacement reveals the following:

(1) Under identical seismic wave conditions, as peak acceleration increases, there is an observable increase in inter-story displacement across all experimental conditions, accompanied by a decrease in structural stiffness and damping ratios. Compared to the pure frame structure, the new structure exhibits lower interlayer displacement values, indicating enhanced shock absorption capabilities. As peak acceleration exceeds 0.4 g, a reduction in damping effectiveness is observed: EL Centro from 66% to 53%, Taft wave from 83% to 26%, and Lanzhou artificial wave from 76% to 48%. This reduction is attributed to structural damage. Additionally, the damping effect becomes increasingly pronounced with the elevation of the floors. For instance, on the fourth floor under identical peak accelerations (PGA = 0.2 g) from different seismic waves, the Taft wave exhibits the most significant damping effect, ranging from 78% to 92%, followed by the Lanzhou artificial wave (75% to 84%), with the EL Centro wave demonstrating the least, at approximately 55%.

(2) In the linear elastic stage, the displacement across each layer of the new structure changes linearly, demonstrating an effective failure mechanism. Displacement at the first layer of the model structure increases most rapidly, followed by the second layer, while the third and fourth floors experience slower growth. The reduction in horizontal lateral stiffness in the model structure indicates that failure initiates at the first layer and progresses upward. Compared to the pure frame, the growth in the new structure is slower, reflecting an overall failure mechanism, in contrast to the interlayer failure mechanism observed in the pure frame model.

(3) The curve indicates that the damping effect on the fourth layer is significantly superior to that on the other three layers. In working condition 3 on the fourth floor, the damping effect is most pronounced, reaching up to 92%. On the second and third floors, the damping effect under working condition 4 is notably evident. The primary reason for this is that in working condition 3, dampers are exclusively installed on the fourth floor, whereas in working condition 4, dampers are placed on each side, effectively dissipating energy and damping while maintaining structural stiffness.

Structural shear response analysis

The story shear force of the structure can be obtained by Eq. (3):

where, Vj(t) represents the jth floor shear time history; mj represents the quality of the jth floor; aj(t) denotes the acceleration time history of the jth floor relative to the base. Taking the input table peak acceleration of 0.4 g and 0.8 g as an example, the maximum floor shear force of the pure frame structure and the attached steel frame structure with additional nodal dampers is shown in Fig. 12.

Comparison of floor maximum shear under different working conditions. (a) EL Centro wave peak acceleration 0.8 g floor shear, (b) EL Centro wave peak acceleration 1.0 g floor shear, (c) Lanzhou artificial wave peak acceleration of 0.8 g floor shear, (d) Lanzhou artificial wave peak acceleration of 1.0 g floor shear, (e) Taft wave peak acceleration 0.8 g floor shear, (f) Taft wave peak acceleration 1.0 g floor shear.

Under varying peak ground accelerations (PGAs), the floor shear force in the retrofitted structure occasionally increases due to the enhanced stiffness and damping introduced by the nodal dampers—particularly at 0.8 g (El Centro wave) and 1.0 g (Taft wave). Overall, the attached steel-frame system with viscoelastic nodal dampers exhibits a general reduction in story shear, indicating effective energy dissipation. As shown in Fig. 10, the El Centro wave causes more pronounced variations in shear distribution among floors, whereas the Taft and Lanzhou artificial waves display similar shear trends and damping ranges. These differences highlight the wave-dependent behavior of the system and emphasize the importance of optimized damper configuration to achieve balanced damping performance across all stories.

Conclusion

This study presents a hybrid energy-dissipating structural system integrating an external steel frame, viscoelastic nodal dampers, and the original reinforced concrete (RC) frame. The dampers, installed at RC frame joints via a subframe, enable shear hysteretic energy dissipation, significantly enhancing the structure’s seismic resilience. To assess performance, shaking table tests and numerical simulations were performed on both the original RC frame and the retrofitted hybrid system. Analyses of acceleration, displacement, story shear, and hysteretic behavior under varying seismic excitations demonstrated the system’s superior damping efficiency and clarified its mechanical response mechanisms. These results provide a practical reference for external steel-frame retrofit design and contribute to the optimization of damper configuration and structural detailing in seismic applications.

(1) Under a peak ground acceleration (PGA) of 0.2 g, the model structure remained within the elastic range, whereas at 1.0 g, cracking and concrete fracture propagation indicated an elastic–plastic response. The integration of viscoelastic nodal dampers and external steel frames fundamentally altered the failure mechanism, transforming it from a local interstory mode to a global failure pattern. This transition improved load redistribution, delayed localized damage, and enhanced the seismic resilience and ductility of the overall structure.

(2) Experimental observations and data analysis reveal that damage primarily concentrated near the base of the model, while the upper stories exhibited stronger damping effects. This behavior results from the rigid connection between the external steel frame and the RC base, which increased the stiffness and bending moment concentration in the lower region, thereby limiting deformation and energy dissipation. Conversely, the upper stories, characterized by greater interstory drift, allowed larger damper deformation, leading to more effective energy absorption and improved seismic response at higher elevations.

(3) Comparative analysis of response curves under different working conditions shows that Working Condition 4 achieved the highest damping efficiency, while Working Condition 1 was the least effective. Intermediate configurations displayed variable responses across floors. Excessive dampers increased global stiffness, restricted deformation, and reduced energy dissipation efficiency. These findings emphasize that optimal damper placement and quantity—rather than total number—are critical to achieving balanced stiffness and damping characteristics.

(4) The damper configuration strongly influences the seismic response and overall energy-dissipating behavior of the structure. Compared with the pure RC frame, the retrofitted system exhibited significantly reduced acceleration, interstory displacement, and story shear. The best-performing configuration achieved up to 64% reduction in acceleration and 52.4% reduction in interstory displacement, confirming that rational damper distribution and interaction control are key to maximizing the efficiency of hybrid energy-dissipating systems in seismic retrofitting applications.

Data availability

The experimental·data used·to support·the findings of this study are included·in·the article.

References

Wang, C., Sarhosis, V. & Nikitas, N. Strengthening/retrofitting techniques on unreinforced masonry structure/element subjected to seismic loads: A literature review. Open. Constr. Building Technol. J. 12 (1), 251–268. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6243-052X (2018).

Ghaderi, P. & Goshtaei, S. M. Smart vibration control of structures with unknown structural parameters using integrated virtual synchronization method/linear-quadratic regulator approach. Adv. Control Applications: Eng. Industrial Syst. 2 (3), e48. https://doi.org/10.1002/adc2.48 (2020).

Veismoradi, S. et al. Development and parametric study of a new self-centering rotational friction damper. Eng. Struct. 235, 112097. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2021.112097 (2021).

Zhang, M. & Pang, H. Analysis of damping performance of frame structure with viscoelastic dampers. Eng. Comput. 38 (2), 913–928. https://doi.org/10.1108/EC-02-2020-0116 (2021).

Tremblay, R. et al. Seismic testing and performance of buckling-restrained bracing systems. Can. J. Civ. Eng. 33 (2), 183–198 (2006).

Elias, S. & Matsagar, V. Research developments in vibration control of structures using passive tuned mass dampers. Annu. Rev. Control. 44, 129–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arcontrol.2017.09.015 (2017).

Papagiannopoulos, G. A., Katsimpini, P. S. & Hatzigeorgiou, G. D. Research on the seismic response of hybrid Concrete/Steel structures equipped with the Seesaw system. Vibration 7 (4), 1190–1209. https://doi.org/10.3390/vibration7040061 (2024).

Katsimpini, P., Papagiannopoulos, G. & Hatzigeorgiou, G. A thorough examination of innovative supplementary dampers aimed at enhancing the seismic behavior of structural systems. Appl. Sci. 15 (3), 1226. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15031226 (2025).

Han, B. K. & Won, Y. J. Stochastic seismic performance of TLCD for the passive control of structures. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2, 273–280. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02830481 (1998).

Dutta, A. K., Deb, S. K. & Dutta, A. Design of an active controller for Quincy Bayview Bridge, Illinois, U.S.A. Against seismic excitation-Part II: control implementation. Struct. Control Health Monit. 15 (8), 1078–1104. https://doi.org/10.1002/stc.231 (2010).

Pozo, F. & Rodellar, José, A. L. Acceleration Feedback Control of Hysteretic Base-Isolated Structures: Application to a Benchmark Case. Ifac Proc. Vol. 41(2), 2526–2531. https://doi.org/10.3182/20080706-5-KR-1001.00426 (2008).

Xu, H. et al. Shaking table test and investigation of rocking effect in a high-rise isolated structure. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Struct. Build. 8, 174. https://doi.org/10.1680/jstbu.20.00268 (2021).

Zhou, Y. et al. A displacement-based seismic design method for Building structures with nonlinear viscoelastic dampers. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 19 (11), 4535–4585. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10518-021-01135-8 (2021).

Xie, L. et al. Uniform damping ratio-based design method for seismic retrofitting of elastoplastic RC structures using viscoelastic dampers. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 128, 105866. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soildyn.2019.105866 (2020).

Yao, J. T. P. Concept of structural control. J. Struct. Div. 98 (7), 1567–1574. https://doi.org/10.1061/JSDEAG.0003280 (1972).

Clough, R. W. & Huckelbridge, A. A. Preliminary Experimental Study of Seismic Uplift of a Steel frame[M] (Earthquake Engineering Research Center, College of Engineering, University of California, 1977).

Yim, C. S., Chopra, A. K. & Penzien, J. Rocking response of rigid blocks to earthquakes. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn.. 8 (6), 565–587. https://doi.org/10.1002/eqe.4290080606 (1980).

Zhang, R. H. & Soong, T. T. Seismic design of viscoelastic dampers for structural applications. J. Struct. Eng. 118 (5), 1375–1392. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9445(1992)118:5(1375) (1992).

Tezcan, S. S. & Uluca, O. Reduction of earthquake response of plane frame buildings by viscoelastic dampers. Eng. Struct. 25 (14), 1755–1761. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2003.07.001 (2003).

INAI, E. & FUJIMOTO, T. Earthquake response characteristic of steel frame with viscoelastic damper. STEEL Constr. Eng. 11 (44), 63–74. https://doi.org/10.11273/jssc1994.11.44_63 (2004).

Benedetti, A., Landi, L. & Merenda, D. G. Displacement-based design of an energy dissipating system for seismic upgrading of existing masonry structures. J. Earthquake Eng. 18 (4), 477–501. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632469.2014.897274 (2014).

Lee, M., Lee, J. & Kim, J. Seismic retrofit of structures using steel honeycomb dampers. Int. J. Steel Struct. 17, 215–229. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13296-015-0101-5 (2017).

Li, Z. & Shu, G. Optimal placement of metallic dampers for seismic upgrading of multistory buildings based on a cost-effectiveness criterion using genetic algorithm. Struct. Des. Tall Special Build. 28 (6), e1595. https://doi.org/10.1002/tal.1595 (2019).

Peng, Y. & Zhang, Z. Optimal MR damper–based semiactive control scheme for strengthening seismic capacity and structural reliability. J. Eng. Mech. 146 (6), 04020045. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)EM.1943-7889.0001768 (2020).

Yang, H. et al. Shaking table test study on seismic performance of RC frame structure with NES[C]. Structures. 47, 153–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.istruc.2022.11.057 (2023).

Maida, Y. & Sakata, H. Finite element analysis of reinforced concrete frames with Bracing-Friction dampers for seismic resistance. J. Earthquake Eng. 27 (14), 3975–3991. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632469.2022.2153946 (2023).

Siami, R. & Tehrani, P. Effects of using different arrangements and types of viscous dampers on seismic performance of intermediate steel moment frames in comparison with different passive dampers. Structures 33 (5), 3382–3396. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.istruc.2021.06 (2021).

He, W. et al. Experimental research on the seismic characteristics of a precast frame structure with a viscous damper. J. Earthquake Eng. 27 (4), 959–980. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632469.2022.2033360 (2023).

Zhang, C. et al. Experimental and numerical investigation on seismic performance of retrofitted RC frame with sector lead viscoelastic damper. J. Building Eng. 44, 103218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2021.103218 (2021).

Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China (MOHURD). Code for Seismic Design of Buildings (GB 50011–2010, 2016 Edition) (China Architecture & Building, 2016) (in Chinese).

Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China (MOHURD). Code for Seismic Test Methods of Buildings (JGJ/T 101–2015) (China Architecture & Building, 2015) (in Chinese).

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jinsheng Shen: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Software, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization Qianpeng Nie: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Software, Resources, Methodology, Data curation, Conceptualization. Shaozhuo Jia: Investigation, Data curation, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shen, J., Nie, Q. & Jia, S. Shaking table tests and analysis of the seismic behavior of external steel frames with viscoelastic nodal dampers. Sci Rep 16, 4157 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34291-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34291-x