Abstract

Debris accumulation around bridge piers and abutments threatens stability by intensifying scour and risking collapse. While the effects of debris on individual bridge components have been studied, the combined influence of debris in the presence of both pier and abutment remains underexplored. This study experimentally examines how debris shape, thickness, and pier-abutment distance affect local scour depth under clear-water conditions. Experiments were conducted in 8 m long, 0.8 m wide, and 0.6 m deep flume, filled with 15 cm of uniform sand (\({d}_{50}=0.83\) mm, \({\sigma }_{g}=1.5\)) and operated at a constant discharge of 30 l/s. Results showed that increasing the relative thickness of rectangular debris from 0.09 to 0.39 lead to a 41% increase in scour depth at the pier and 47% at the abutment. Reducing the pier-abutment distance from 0.2 to 0.1 caused an increase in scour depth by 21% and 16%, respectively. Thicker debris enhanced vortex intensity, resulting in deeper scouring. Among the tested shapes, rectangular debris caused the most significant scour, while triangular debris had the least effect. In all cases, maximum scour occurred at the abutment. These findings emphasize the practical significance of considering debris-structure interactions to improve bridge safety and resilience in engineering design.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Bridges are essential components of transportation networks, providing critical connectivity across water bodies and flood-prone areas1. However, scour-induced failure remains one of the leading causes of bridge collapses worldwide, particularly during extreme hydrologic events2,3. Scour occurs as flowing water erodes sediment around bridge foundations, leading to progressive undermining and potential structural instability4. In the United States, it is estimated that nearly 60% of bridge failures are attributable to scour-related mechanisms5, and similarly, in New Zealand, at least one major bridge failure per year is linked to foundation scour4. If left unaddressed, local scour near bridge piers and abutments can cause severe damage or total structural failure.

The hydrodynamic processes around bridge piers and abutments are highly complex due to the presence of turbulent flow structures, including horseshoe vortices, wake vortices, and shear layers6. Numerous studies have been conducted to understand local scour behavior around bridge elements. Hong7 investigated the influence of pier proximity to abutments, concluding that nearby piers significantly affect the development and deepening of scour depths near abutments. Oben-Nyarko and Ettema8, however, found contrasting results, reporting that the presence of a pier near an abutment does not always substantially increase abutment scour depth. Meanwhile, Ataie-Ashtiani and Beheshti9 and Hang7 demonstrated that reduced pier–abutment distance intensifies horseshoe vortices and consequently increases scour depth. Melville6 emphasized the necessity of considering piers and abutments as a coupled system rather than isolated elements when evaluating scour mechanisms.

One of the problems that river and bridge engineers face is the accumulation of logs and woody debris upstream of the bridge piers and abutments in river bridges. These floating materials are transported by the flow, especially during floods, and can significantly increase local scour around the piers and abutments, altering the riverbed morphology and consequently raising the risk of bridge failure. In addition to causing environmental problems and obstructing flow, debris accumulation plays a crucial role in changing the shape of the riverbed and jeopardizing the structural stability of bridges. Parola et al. (2000) reported that debris accumulation around bridge piers can significantly influence hydrodynamic forces and local scour, depending on the various shapes, roughness, and porosity of the accumulated debris. Moreover, debris accumulation on bridge piers is an ongoing problem that can alter flow conditions, reduce the effective waterway capacity, and increase the risk of bridge failure (Kattell and Eriksson, 1998; Diehl, 1997).

.Debris can partially or fully block bridge openings, increasing flow constriction, turbulence intensity, and thus enhancing local scour around piers and abutments10,11. Laursen and Toch12, Melville and dongol13, Diehl14, Parola et al.15, Lagasse et al.16, Rahimi et al.17, Kosic et al.18 and Dadamahalleh et al.19 summarized the qualitative impacts of large woody debris accumulation on bridges, highlighting the associated risks of increased scour and structural vulnerability. Wallerstein and Thorne20 and Wallerstein et al.21, through studies based on Mississippi River conditions, attributed debris presence largely to bank erosion processes. Several experimental studies have specifically examined how debris characteristics—such as shape, thickness, and placement—affect local scour around piers. The accumulation of large woody debris has been found to enlarge both the width and depth of scour depths, with the severity depending on debris size and hydraulic conditions16,20. Schalko et al.22 found that large wood (LW) accumulation at bridge piers is primarily governed by the approach flow velocity and log length. Consistently, Palermo et al.23 demonstrated that large debris surrounding bridge piers increases shear stress, flow turbulence, and consequently the scour depth. According to Al-Jubouri et al.24, debris characteristics significantly influence local scour patterns. Furthermore, Pagliara et al.25 indicated that bed slope plays a critical role in scour morphology, especially in the presence of large debris accumulations. The type and placement of debris also influence scour intensity; Khalili et al.26 reported that buried debris causes greater scour depth and width compared to free debris, while Zhang et al.27 showed that dynamic debris jams can double scour depth and increase scour volume up to eight times, generating additional hydraulic head proportional to jam size and Froude number. Al-Khafaji et al.28 revealed that successive bridges can reduce downstream pier scour by 30–40%, whereas debris accumulation intensifies contraction scour by up to 40.5%. Research by Abousaeidi et al.29 demonstrated that debris thickness and pier-abutment proximity substantially influence scour depths. Their experiments indicated an inverse correlation between pier–abutment distance and scour depth, while debris thickness and length were positively associated with deeper scour depths. Notably, rectangular debris produced the most significant scour depths, followed by cylindrical and triangular shapes, with scour depths consistently higher near abutments compared to piers. While these studies have substantially advanced our understanding of scour mechanisms, a critical gap remains: most existing research has evaluated either structural distance or debris effects in isolation, without a combined analysis. Several experimental studies have investigated measures to reduce pier scour in the presence of debris. For instance, the use of slots, collars, and riprap has been shown to decrease scour depth, although their effectiveness depends on the shape and position of debris. Debris accumulation can also amplify morphological changes, such as increasing bedform heights, which can be partially mitigated by auxiliary structures like sills.30,31,32,33.

Despite significant progress in understanding local scour, the combined effects of debris geometry and pier–abutment interaction remain insufficiently studied. This study addresses this gap by examining how debris shape and thickness, together with the spacing between the pier and abutment, influence flow patterns and scour development. The results show that floating debris can substantially intensify scour around both piers and abutments, highlighting the importance of considering debris effects in the design and management of river structures. The main contribution of this research is the development of an integrated understanding of debris-induced scour mechanisms, which improves the accuracy of scour depth predictions and provides practical guidance to river engineers for the design and maintenance of hydraulic structures exposed to floating debris, ultimately supporting more resilient bridge infrastructure under flood conditions.

Materials and methods

Experimental setup

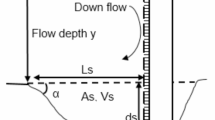

The experiments were conducted at the Water and Hydraulic Structures Laboratory of Department of Water Science and Engineering, Shahid Bahonar University of Kerman, Kerman, Iran. A straight rectangular flume, 8 m long, 0.8 m wide, and 0.6 m deep, with a flat concrete bed and glass sidewalls, was employed. Water was supplied from an underground reservoir using two centrifugal pumps, and the discharge was controlled by a volumetric flowmeter with an accuracy of ± 1%. Flow depth was regulated using an adjustable tailgate at the downstream end. A flow straightener installed at the inlet minimized turbulence and ensured uniform, steady flow conditions. A constant discharge of 30 L/s was selected, resulting in a flow depth of approximately 16.5 cm. The sediment bed consisted of uniform, noncohesive sand with a median particle size of d₅₀ = 0.83 mm and a geometric standard deviation σg = 1.5. These sediment characteristics were selected based on the criteria proposed by Raudkivi and Ettema34 (d₅₀ > 0.7 mm to avoid ripple formation) and by Chiew and Melville35 (σg < 1.3 to minimize sediment-heterogeneity effects). In addition, following Oliveto and Hager36, the flow depth was maintained above 20 mm to avoid roughness-induced suppression of scour depth, and according to Melville and Hadfield37, the pier-diameter–to–flow-depth ratio was kept below 0.7 to prevent scale effects on scour. The bridge substructure comprised a cylindrical steel pier (diameter = 30 mm) and a steel abutment (6 × 12 × 45 cm). Both elements were mounted on a false floor positioned 0.16 m above the main flume bed to realistically simulate a riverbed condition. The relative distance between pier and abutment different at 0.1 and 0.2 times the pier diameter to investigate interaction effects. Debris was simulated using fixed wooden models positioned upstream of the pier. Three debris shapes—rectangular, triangular, and semicircular (half-cylindrical)—were tested. The relative debris thickness varied from 0.09 to 0.39. These geometries were selected to represent typical forms of natural debris (e.g., floating logs). A schematic of the setup, model positions, and debris configurations is presented in Fig. 1.

All tests were performed under clear-water conditions. Scour equilibrium was defined following Kumar et al.38, as the stage at which bed-level variations were less than 1 mm over a 3-h period. Each experiment was continued for 7 h to ensure that equilibrium scour conditions were fully achieved (Fig. 2). Scour depth and bed topography were measured using a point gauge with a precision of 0.1 mm at predefined grid locations. After equilibrium was reached, these grid points were recorded to obtain detailed scour profiles. The three-dimensional scour hole morphology was subsequently plotted and analyzed using Surfer 16 software. This setup provided a controlled environment to examine the combined influence of debris characteristics and pier–abutment interaction on local scour evolution.

Dimensional analysis

Twenty key characteristic parameters affecting the local scour around bridge pier and abutment identified in Eq. 1.

where ds (scour depth), B (channel width), D (foundation diameter), \({d}_{ap}\)(distance between pier and abutment), d50 (average particle diameter of sediment), g (gravitational acceleration), h (flow depth), \({K}_{s}\) (roughness), \({K}_{p}\) (permeability of woody debris), La (abutment length), Ld (debris length), \(\text{SF}\) (debris shape factor) is determined based on the drag coefficients of various debris shapes. \({\text{T}}_{\text{d}}\) debris diameter), \({t}_{ex}\) (experimental time), \({t}_{eq}\) (equilibrium time), U (flow velocity), Wa (abutment width), Wd (debris width), ρ (fluid density), μ (kinematic viscosity of the fluid), ρs (sediment density) and σg is the geometrical standard deviation of sediment particles,. Using dimensional analysis based on the Buckingham π theorem, the following dimensionless relationship was derived. Using dimensional analysis based on the Buckingham π theorem, the following dimensionless relationship was derived, leading to Eq. (2). Since the debris bodies were smooth (\({K}_{s}=0\)) and non-permeability of woody debris (\({K}_{p}=0\)), their related parameters were not included in Eq. (2).

The dimensionless parameter B/h represents the aspect ratio indicating wide channel conditions, while \({\text{F}}_{\text{r}}\) and \({\text{R}}_{\text{e}}\) denote the Froude and Reynolds numbers, respectively. In river engineering analyses, such as pier and abutment scour studies, due to the non-dimensional of \({\text{F}}_{\text{r}}\) and \({\text{R}}_{\text{e}}\), the high range of Reynolds numbers in the flow, and the dominant influence of the Froude number, scaling errors are negligible and can be justifiably disregarded. According to the experimental conditions of this study, the effect of fluid viscosity parameters was neglected due to the large Reynolds number (\({R}_{e}\ge 2000\)). The sediment particle size, d50 = 0.83 mm, \({\text{G}}_{\text{s}}\) . \(\frac{{\text{d}}_{50}}{\text{h}}=0.005\) and \({\upsigma }_{\text{g}}\) < 1.3. All experiments were conducted for a duration equal to the equilibrium scour time (\({t}_{ex}/{t}_{eq}=1\)). In addition, some geometrical parameters of physical models (B, \({\text{L}}_{\text{a}}\), \({\text{W}}_{\text{a}},\) \({\text{L}}_{\text{d}}\) and \({\text{W}}_{\text{d}}\)) had constant values through all experiments. Since these parameters remained constant, they were excluded from the Eq. (2), resulting in the simplification of Eq. (2) to Eq. (3)

All parameters investigated in this study, including geometric, hydraulic, and sediment characteristics, are schematically illustrated in Fig. 3.

Results and discussion

The experiments in this research investigate the effect of debris on local scour around the bridge pier and abutment. Debris with different shapes (such as rectangular, semi-circular and triangular) and four values of the relative debris thickness (\({T}_{d}/h\)) (0.09, 0.19, 0.29 and 0.39) were attached to the bridge pier in a submerged state at a relative distance from the sediment bed surface. The bridge piers were positioned at relative distances of 0.1 and 0.2 from the bridge abutment (\({d}_{ap}/B\)). This section explains the effects of the relative thickness and shape of debris at different distances between the bridge pier and abutment, specifically for rectangular debris on local scour depth.

Influence of shape and relative thickness of debris on bridge pier and abutment scour

In this section, the effect of the relative thickness of debris (\({T}_{d}/h\)) on bridge pier and abutment scour was investigated. The experiments were conducted with three geometric shapes of debris: rectangular, semi-circular and triangular, with four relative thicknesses (\({T}_{d}/h\)) of 0.09, 0.19, 0.29, and 0.39.

Observations showed that as the relative thickness of debris (\({T}_{d}/h\)) increases, the scour depth also increases. With an increasing relative debris thickness (\({T}_{d}/h\)), more intense vortex systems developed around the bridge pier and abutment. These vortices detach sediment particles from the riverbed and transport them downstream with the main flow. This enhanced vortical action significantly influenced the maximum relative scour depth (\({d}_{s\_max}/h\)) at both the pier front and the abutment region.

According to Fig. 4, experiments conducted on the three debris shapes (rectangular, semi-circular, and triangular) at a relative distance of 0.1 from the abutment (\({d}_{ap}/B\)) under identical laboratory conditions demonstrate that the rectangular debris generates a larger scour depth compared to the semi-circular and triangular shapes. This can be attributed to the larger blockage effect of rectangular debris, which intensifies flow acceleration around the pier and enhances sediment entrainment. The sharper edges and flat surfaces of rectangular debris created stronger localized vortices compared to the smoother surfaces of semi-circular and triangular debris, thereby increasing scour depth in the pier and abutment regions.

Table 1 and Fig. 5 illustrate the effect of the relative thickness of debris (\({T}_{d}/h\)) for the three geometric shapes: rectangular, semi-circular, and triangular. At a relative distance of 0.1 between the pier and abutment (\({d}_{ap}/B\)), when the relative thickness (\({T}_{d}/h\)) of rectangular debris increased from 0.09 to 0.39, the maximum relative scour depth (\({d}_{s\_max}/h\)) increased by 42% in front of the bridge pier and by 47% at the front nose of the bridge abutment. Furthermore, at the same relative distance of 0.1 between the pier and abutment (\({d}_{ap}/B\)), as the relative thickness of the debris (\({T}_{d}/h\)) increased from 0.09 to 0.39, the maximum relative scour depth (\({d}_{s\_max}/h\)) in the presence of semi-circular and triangular debris increased by 30% and 45% in front of the bridge pier, and by 43% and 31% at the front nose of the bridge abutment, respectively. This result is consistent with the observations of Al-Jubouri et al. (2024), who reported that increasing the thickness of floating debris from T/Y = 0.25 to T/Y = 0.5 leads to an increase of up to 5 cm in scour depth around the bridge pier40.

These results underscore the amplifying role of debris thickness in exacerbating local scour through enhanced flow constriction and vortex formation, particularly in confined pier-abutment geometries. The observed increases align with the principle that debris accumulation intensifies shear stresses and turbulence around bridge elements, leading to deeper scour holes39,40. For rectangular debris, the higher scour amplification (42–47%) compared to semi-circular (30–43%) and triangular (31–45%) shapes can be attributed to its sharper edges, which promote greater flow blockage and horseshoe vortex development, consistent with experimental observations on debris-induced scour mechanisms11,24. Comparing parts (a) and (b) of Fig. 5 reveals that the maximum relative scour depth (\({d}_{s\_max}/h\)) at the front nose of the bridge abutment was consistently greater than the maximum relative scour depth (\({d}_{s\_max}/h\)) in front of the bridge pier. This pattern was most pronounced for rectangular debris, where abutment scour depths exceeded pier scour by up to 12% (47% vs. 42% increase relative to baseline), followed by semi-circular (13% difference: 43% vs. 30%) and triangular debris (14% difference: 31% vs. 45%, though triangular showed a reversed trend at the pier). These observations stem from clear-water scour experiments in a controlled flume, highlighting the amplified erosive forces at the abutment due to flow acceleration and vortex intensification in confined geometries. This disparity underscores the role of pier-abutment interactions in redistributing hydraulic forces, where the abutment nose experiences enhanced downflow and shear stresses from the converging flow field, leading to deeper scour holes compared to the pier front 24,41. The consistent superiority of abutment scour aligns with established scour mechanics, where abutment geometries promote stronger horseshoe vortices and secondary currents that erode sediment more aggressively than isolated pier-induced vortices. For rectangular and semi-circular debris, the abutment’s exposure to debris-induced flow constriction exacerbates this effect, resulting in greater relative depths, whereas triangular debris’s upstream positioning may partially shield the pier while still amplifying abutment scour through turbulence spillover11,39.

The results obtained from the analysis of experiments in this research demonstrate that the maximum relative scour depth (\({d}_{s\_max}/h\)) occurs when the debris is rectangular in shape. Therefore, the focus of this study and the experiments has been directed towards examining and analyzing the maximum scour depth under conditions where rectangular debris is present, and the results have been thoroughly discussed and evaluated. This approach is prudent for engineering practice, as it addresses the worst-case scenario for scour risk assessment and management. Effective debris management and scour protection measures should prioritize the removal of block-like debris and focus monitoring efforts on the vulnerable abutment region.

Interactive effect of bridge pier and abutment on scour in the presence of rectangular debris

In this research, experiments were conducted with rectangular debris of relative thicknesses (\({T}_{d}/h\)) of 0.09, 0.19, 0.29, and 0.39 at two relative distances of (0.1 and 0.2) between the bridge pier and abutment (\({d}_{ap}/B\)). Figure 6 illustrates the experiments conducted to measure scour depth around the bridge pier and abutment with rectangular debris of relative thickness (\({T}_{d}/h\)) = 0.19 at two relative distances (0.1 and 0.2) between the bridge pier and abutment (\({d}_{ap}/B\)).

The variation in the distance between the bridge pier and abutment (\({d}_{ap}/B\)) leads to changes in the flow cross-section, flow velocity, and shear stress exerted by the flow on the sedimentary bed6. In this research, by examining the interactive effect of the bridge pier and abutment on scour, it was determined that a decrease in the distance between the bridge pier and abutment (\({d}_{ap}/B\)) intensifies the flow velocity between them, leading to an increase in scour depth. According to Fig. 7, the maximum relative scour depth (\({d}_{s\_max}/h\)) at the bridge pier and abutment in the presence of rectangular debris with a relative thickness (\({T}_{d}/h\)) of 0.39 increased by 22% and 16%, respectively, at a relative distance (\({d}_{ap}/B\)) of 0.1 compared to a relative distance (\({d}_{ap}/B\)) of 0.2. This behavior is also consistent with Melville’s findings6; he states that reducing the spacing between structures leads to increased contraction scour and intensified vortex interaction, which can increase scour depth by approximately 20–25%. Furthermore, the results align with studies by Laursen and Toch12, as they demonstrated that the geometry of the pier and abutment and their reduced spacing lead to increased hydraulic forces, consequently raising scour depth by 15–30%12; a trend also observed in this research when comparing the two distances of 0.1 and 0.2. Regarding pier and abutment scour interaction, the findings of Oben-Nyarko and Ettema8 also confirm this behavior. They reported that the placement of a pier in close proximity to an abutment (approximately 0.1 to 0.2 times the pier width) causes the overlapping of horseshoe vortices, increasing combined scour depth by 10–20%3; a trend similar to the current results and the observed scour increase at a \({d}_{ap}\)/B = 0.1 distance. Furthermore, a comparison of the maximum relative scour depth (\({d}_{s\_max}/h\)) for three different shapes of debris (rectangular, semi-circular, and triangular) with relative thicknesses (\({T}_{d}/h\)) of 0.09, 0.19, 0.29, and 0.39 indicates that relative thicknesses (\({T}_{d}/h\)) less than 0.2 have a minimal impact on increasing the maximum scour depth, as these configurations result in limited flow blockage and subdued vortex formation, particularly when debris is placed upstream or near the bed, consistent with experimental observations on submersion ratios and debris elevation39,41,42.

These findings highlight the synergistic role of structural proximity and debris geometry in exacerbating local scour under clear-water conditions, where reduced \({d}_{ap}/B\) ratios enhance flow acceleration in the gap, promoting deeper erosion at both pier and abutment locations6,18. The 22% pier scour increase at \({d}_{ap}/B=0.1\) for rectangular debris underscores the pier’s greater sensitivity to contraction-induced downflow, while the 16% abutment rise reflects amplified shear stresses at the nose due to converging streamlines6,40. For lower \({T}_{d}/h (>0.017)\), the negligible amplification aligns with scenarios where debris submersion is insufficient to significantly alter the horseshoe vortex dynamics, leading to scour depths comparable to no-debris baselines39,41.

Table 2 and Fig. 8 illustrate the variations in the maximum relative scour depth (\({d}_{s\_max}/h\)) with respect to changes in the thickness of rectangular debris for two relative distances (\({d}_{ap}/B\)) of 0.1 and 0.2. Observations indicate that the maximum relative scour depth for debris with a relative thickness (\({T}_{d}/h\)) of 0.09 at a relative distance (\({d}_{ap}/B\)) of 0.1, compared to a relative distance (\({d}_{ap}/B\)) of 0.2 between the pier and bridge abutment, increased by 8% at the bridge abutment (\({d}_{s\_max(A)}/h\)) and by 4% at the bridge pier (\({d}_{s\_max(P)}/h\)). These modest increases at low \({T}_{d}/h\) highlight the onset of proximity-induced amplification, where closer spacing (\({d}_{ap}/B=0.1\)) subtly elevates baseline scour through minor flow accelerations, aligning with integrated models that predict 5–10% enhancements in confined channels even under minimal debris loading. At \({T}_{d}/h=0.09\), the 8% abutment increase versus 4% at the pier further underscores this asymmetry, with debris constriction in narrow gaps (\({d}_{ap}/B=0.1\)) disproportionately affecting the abutment due to amplified shear stresses40,41.

In summary, the interaction between a bridge pier and abutment creates a compounded scour hazard, which is severely exacerbated by the presence of rectangular debris. The key controlling factors are the relative distance (\({d}_{ap}/B\)) and the relative debris thickness (\({T}_{d}/h\)). A smaller distance (0.1) and a larger thickness (exceeding ~ 0.25) represent the worst-case scenario, with the abutment consistently showing greater vulnerability.

While studies such as those by Kandasamy and Melville44 primarily focused on flow intensity and its effect on piers and abutments, with less attention paid to the role of debris , the present research addresses this gap by investigating the shape and thickness of debris, demonstrating that debris with thicknesses exceeding 0.3h has a significant impact on increasing scour [current study]. Furthermore, the results regarding debris shape differences are consistent with the findings of Raikar and Dey45, who emphasized that the geometric characteristics of an obstruction can influence vortex patterns and consequently alter scour depth.

Longitudinal and transverse profiles of scour hole around bridge pier and abutment

The investigation of the scour hole along the flow path is crucial for understanding the scouring mechanism. Measuring longitudinal and transverse profiles of the scour hole and determining the scour volume in laboratory studies helps identify the dimensions and shape of the scour hole, which is useful for the calibration and validation of numerical models. Figure 9 illustrates the longitudinal profiles of scour around the bridge abutment, and Fig. 10 presents the profiles around the bridge pier, located along the upstream and downstream bed relative to the sediment depth, both with and without debris, for a discharge (Q) of 30 l/s.

As shown in these figures, the accumulation of debris enlarges scour hole dimensions and results in sediment transport to farther downstream locations. In other words, the accumulation of debris around these structures reduces the flow cross-section, generates stronger horseshoe and wake vortices around the bridge pier and abutment, and leads to larger scour depths. This process causes sediment erosion and transport downstream, as well as increased scour depth. Furthermore, when flow passes through the scour hole, due to the increased flow depth, the Froude number decreases before entering the downstream bed of the scour depth, resulting in less erosion compared to the upstream bed, aligning with experimental findings where downstream profiles show 20–30% reduced erosion due to wake-induced flow deceleration and lower shear stresses. As shown in the cross-sectional profile in Fig. 11, debris accumulation leads to an increase in the dimensions of the scour hole.

Therefore, the scour depth around the bridge abutment is consistently greater than that around the pier due to the formation of stronger vortices in its vicinity.

Figures 12 and 13 illustrate the topography and contour lines of the sedimentary bed after conducting the experiment with rectangular debris at four relative thicknesses (\({T}_{d}/h\)=0.09, 0.19, 0.29 and 0.39), at a relative distance of 0.2 between the bridge pier and abutment (\({d}_{ap}/B\)).

The results indicate that the thickness of debris significantly affects the local scour depth. Thicker debris generates stronger vortices around the pier and abutment, which enhance sediment entrainment from the bed and lead to deeper and more pronounced scour holes. These vortices increase turbulent energy near the bed and accelerate sediment transport downstream. Consequently, as the debris thickness increases, the local scour depth also increases. According to the experimental results, the scour holes at the pier and abutment were deepest in the presence of debris with a relative thickness of 0.39, which produced the strongest vortices, while debris with a relative thickness of 0.09 generated the weakest vortices and resulted in relatively shallower scour holes. In particular, the scour hole depth around the pier and abutment increased by about 89.19% compared to the control case in the presence of rectangular debris with a relative thickness of 0.39. For instance, the scour depth at the pier and abutment with debris of relative thickness 0.09 was approximately 60.72% lower than that observed with debris of relative thickness 0.39, consistent with wood debris studies showing low-thickness accumulations (\({T}_{d}/h<0.17\)) producing 50–70% shallower holes due to minimal vortex development . As observed, the scour volume increased with the relative thickness of the rectangular debris (\({T}_{d}/h\)), with the maximum volume occurring at \({T}_{d}/h=0.39\) and the minimum at \({T}_{d}/h=0.09\). The detailed topographic and contour maps (Figs. 12 and 13) are invaluable, as they visually and quantitatively capture the full three-dimensional nature of the scour hole, which is often more critical for structural stability than the maximum depth alone. The evolution of the scour hole’s planform shape with increasing debris thickness, from a localized depression to an extensive, merged erosion zone, clearly demonstrates the escalating risk to foundation integrity.

These profiles and volumes reveal the three-dimensional scour morphology, where debris-induced vortices expand the hole’s upstream extent and downstream deposition, with abutment scour holes showing 20–30% larger volumes than pier holes due to persistent main-channel exposure. The 89.19% depth increase at \({T}_{d}/h=0.39\) underscores rectangular debris’s role in vortex amplification, exceeding smoother shapes by 15–25% in comparable contractions.

Predicting maximum scour depth in the presence of debris

In this study, an empirical equation (Eq. 4) was developed to predict the maximum scour depth around the bridge pier and abutment in the presence of debris, and this equation was derived within the range of the experiments conducted in this research. In formulating this equation, the importance of incorporating the geometric properties of the debris as a key parameter was identified according to the Eq. 3 of the dimensional analysis. Previous studies have also emphasized the significant role of pier-abutment geometry in determining the patterns and intensity of scour.

According to this equation, the parameter \(\frac{{d}_{s}}{h}\) has a direct relationship with \(SF\) and \(\frac{{T}_{d}}{h}\), and an inverse relationship with \(\frac{{d}_{ap}}{B}\). SF values for rectangular, semicircular, and triangular debris were considered 1.5, 0.95, and 0.55, respectively (Munson et al., 2021, White, 2456). The derived empirical equation demonstrates high accuracy in predicting the maximum scour depth, with a determination coefficient (R2) of 0.997, indicating excellent agreement with the experimental results.

Table 3 presents a comparative summary of the results of previous studies and the findings of the present study regarding the effects of debris shape, relative debris thickness (\({T}_{d}/h\)), and relative pier–abutment distance (\({d}_{ap}/B\)) on local scour.

Conclusions

The accumulation of wood and other floating debris upstream of bridge piers and abutments is a critical issue in river and bridge engineering, as it can alter riverbed morphology, intensify localized scour, and compromise the stability of structures. To better understand these effects, this study experimentally investigated the influence of debris thickness and shape on local scour around a bridge pier and abutment, as well as the interactive effects between the pier and abutment in the presence of rectangular debris. Debris with rectangular, semi-circular, and triangular geometric shapes was used, with relative thicknesses (\({T}_{d}/h\)) of 0.09, 0.19, 0.29, and 0.39. The experiments were conducted at two relative distances of 0.1 and 0.2 between the bridge pier and abutment (\({d}_{ap}/B\)). The results demonstrated that debris thickness (\({T}_{d}/h\)) has a significant influence on scour around the bridge pier and abutment. As \({T}_{d}/h\) increases, stronger vortices are generated around the bridge pier and abutment, leading to an increase in the maximum scour depth. Observations revealed that the debris shape significantly affects the scouring process. In descending order, rectangular, semi-circular, and triangular debris created greater scour depths. At a relative distance of 0.1 (\({d}_{ap}/B\)), rectangular debris with a relative thickness (\({T}_{d}/h\)) of 0.24 increased the maximum scour depth (\({d}_{s}/h\)) in front of the bridge pier by 10.71% and 14.81% and at the abutment nose by 1.47% and 4.54%, compared to semi-circular and triangular debris with the same relative thickness, respectively. Furthermore, at the same relative distance of 0.2 (\({d}_{ap}/B\)), rectangular debris with \({T}_{d}/h\)=0.39 increased the maximum scour depth (\({d}_{s\_max}/h\)) around the bridge pier and abutment by 41.67% and 47.27%, respectively, compared to rectangular debris with \({T}_{d}/h\)=0.09. The results also indicated that increasing the distance between the bridge pier and abutment significantly impacts the scour depth volume; as this distance increases, the scour depth volume exhibit a corresponding increase. In the case of rectangular debris with \({T}_{d}/h\)=0.39, the maximum relative scour depth (\({d}_{s\_max}/h\)) in front of \({d}_{ap}/B\)=0.2 increased by 21.42% and 15.71%, respectively, compared to \({d}_{ap}/B\)=0.1. According to the results, the scour depth around the bridge abutment consistently exceeded that observed around the pier, which can be attributed to the formation of stronger vortices in the vicinity of the abutment. The findings demonstrated that the presence of debris in front of the bridge pier and abutment intensifies the scour depth, potentially leading to bridge failure and resulting in significant financial losses and casualties. Therefore, further research is necessary to prevent and mitigate scour development around bridge piers and abutments. Future studies could focus on investigating the influence of woody debris around abutments or groups of piers to provide a deeper understanding of their effects on scour characteristics and flow dynamics.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article. More information is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- B:

-

Width of flume

- \(D\) :

-

Diameter of pier

- \({d}_{s\_max}\) :

-

Maximum scour depth

- \({d}_{s\_max(P)}\) :

-

Maximum scour depth at pier.

- \({d}_{s\_max(A)}\) :

-

Maximum scour depth at abutment

- \({d}_{50}\) :

-

Average particle diameter of sediment

- \({d}_{aP}\) :

-

Distance between pier and abutment

- \({F}_{r}\) :

-

Froude number

- \({G}_{s}\) :

-

Specific gravity

- H :

-

Flow depth

- \({K}_{s}\) :

-

Roughness

- \({K}_{p}\) :

-

Permeability of woody debris

- \({L}_{a}\) :

-

Length of abutment

- \({L}_{d}\) :

-

Length of debris

- Q :

-

Discharge

- SF :

-

Debris shape factor

- \({T}_{d}\) :

-

Thickness of debris

- \({t}_{ex}\) :

-

Experiment time

- \({t}_{eq}\) :

-

Equilibrium time

- \({U}_{c}\) :

-

Critical velocity

- \({W}_{a}\) :

-

Width of abutment

- \({W}_{d}\) :

-

Width of debris

- \({\sigma }_{g}\) :

-

Geometric standard deviation of sediments particle

- Rec:

-

Rectangular

- Semi-C:

-

Semicircular

- Tri:

-

Triangular

References

Guikema, S. & Gardoni, P. Reliability estimation for networks of reinforced concrete bridges. J. Infrastruct. Syst. 15(2), 61–69. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)1076-0342(2009)15:2(61) (2009).

Millar, B., Hamill, G., Taylor, S. & Robinson, D. ArchIMEDES: Computer Vision Tracking of the Inherent Changes to Structural Stability of Masonry Arch Bridges. Resulting from Increased Bed Scour. e-J. Nondestruct. Test. https://www.ndt.net/?id=29586 (2024).

Khalid, M. & Danish, M. A. review of the scour management for mitigating the bridge failure. https://doi.org/10.47531/SIC.2022.33 (2019).

Melville, B.W. & Coleman, S.E. Bridge scour (Water Resources Publication, 2000).

Lagasse, P.F., Clopper, P.E., Zevenbergen, L.W. & Girard, L.W. Countermeasures to protect bridge piers from scour. NCHRP Report 593, National cooperative highway research program (Transportation Research Board of The National Academies, Washington, D.C, 2007).

Melville, B. Pier and abutment scour–an integrated approach. J. Hydraul. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9429(1997)123:2(125) (1997).

Hong, S. Interaction of bridge contraction scour and pier scour in a laboratory river model. M.S.thesis. Civil and Environmental Deep. Georgia Inst.of Technology (Atland, 2005).

Oben-nyarko, K. & Ettema, R. Pier and abutment scour interaction. J. Hydraul. Eng. ASCE 137, 1599–1605. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)HY.1943-7900.0000446 (2011).

Ataie-Ashtiani, B. & Beheshti, A. Experimental investigation of clear-water local scour at pile groups. J. Hydraul. Eng. 132(10), 1100–1110. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9429(2006)132:10(1100) (2006).

Panici, D. & Kripakaran, P. Characterizing the importance of porosity of large woody debris accumulations at single bridge piers on localized scour. Water Resour. Res. 59(9), e2022WR033531. https://doi.org/10.1029/2022WR033531 (2023).

Pagliara, S. & Carnacina, L. Influence of wood debris accumulation on bridge pier scour. J. Hydraul. Eng. ASCE https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)HY.1943-7900.0000289 (2011).

Laursen, L.M. & Toch, A. Scour around bridge piers and abutments. Bulletin, 4, Iowa road research board, https://publications.iowa.gov/id/eprint/20237 (1956).

Melville, B. W. & Dongol, D. M. Bridge pier scour with debris accumulation. J. Hydraul. Eng. 118(9), 1306–1310. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9429(1992)118:9(1306) (1992).

Diehl, T.H. Potential Drift Accumulation at Bridge. Report No. FHWARD -97–026 Hydraulic Engineering, No. 9 Federal Highway Administration Washington D.C (1997).

Parola, A.C., Apelt, C.J. & Jempson, M.A. Debris Forces on Highway Bridges. NCHRP Report No. 445 Transportation Research Record Transportation Research Board, Washington D.C; 176 (2000).

Lagasse, P.F., Zevenbergen, L.W. & Clopper, P.E. Impacts of debris on bridge pier scour In Scour and Erosion 854–863 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1061/41147(392)85.

Rahimi, E., Qaderi, K., Rahimpour, M. & Ahmadi, M. M. Effect of debris on piers group scour: An experimental study. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 22(4), 1496–1505. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12205-017-2002-y (2018).

Kosic, M., Prendergast, L. J. & Anzlin, A. Analysis of the response of a roadway bridge under extreme flooding-related events: Scour and debris-loading. Eng. Struct. 279, 115607. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2023.115607 (2023).

Dadamahalleh, P. A., Hamidi, M. & Khalili, A. M. Bed sill effect on bridge pier scour with debris obstruction: An experimental investigation. Innov. Infrastruct. Sol. Springer 9(5), 142 (2024).

Walleerstein, N. & Thome, C.R. Impact of wood debris on fluvial processes and channel morphology in stable and unstable stream 162 (US Army Research Development and standardization Group UK, London, 1996).

Walleerstein, N., Thome, C.R. & Doyle, M.W. Spatial distribution and impact of large woody debris in nor them Mississippi. in Proceedings of the conference a Management of Landscapes Disturbed by Channel Incision May 19–23 145–150 (1997).

Schalko, I., Schmocker, L., Weitbrecht, V. & Boes, R. M. Laboratory study on wood accumulation probability at bridge piers. J. Hydraul. Res. 58(4), 566–581. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221686.2019.1625820 (2019).

Palermo, M., Pagliara, S. & Roy, D. Effect of debris accumulation on scour evolution at bridge pier in bank proximity. J. Hydrol. Hydromech. 69(1), 108–118. https://doi.org/10.2478/johh-2020-0041 (2021).

Al-Jubouri, M., Ray, R. P. & Al-Khafaji, M. S. Unraveling Debris-Enhanced local scour patterns around non-cylindrical bridge piers: Experimental insights and innovative modeling. Sustainability 15(22), 15910. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152215910 (2023).

Pagliara, S., Palermo, M. & Cospolici, O. Effect of bed slope on scour morphology at bridge piers with debris accumulation. in Proceedings of the 10th International Symposium on Hydraulic Structures (ISHS 2024) 11–18 (ETH Zurich, 2024). https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-b-000675942.

Khalili, A. M., Hamidi, M. & Dadamahalleh, P. A. Experimental study of the effect of rectangular debris blockage on the scour hole development around a cylindrical bridge pier. Water Pract. Technol. 19(5), 1878–1892. https://doi.org/10.2166/wpt.2024.092 (2024).

Zhang, W., Nistor, I. & Rennie, C. D. Influence of debris jam formed by trees on bridge pier scour. J. Hydraul. Eng. 150(5), 04024035. https://doi.org/10.1061/JHEND8.HYENG-13688 (2024).

Al-Khafaji, M. S., Abdulameer, L. & Al-Awadi, A. T. Investigating the scour at piers of successive bridges with debris accumulation. J. Infrastruct. Preserv. Resil. 6, 23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43065-025-00138-y (2025).

Abousaeidi, Z., Qaderi, K., Rahimpour, M. & Ahmadi, M. M. Experimental investigation of the effect of debris accumulation on the local scour at bridge pier and abutment. J. Water Soil Conserv. https://doi.org/10.22069/JWSC.2018.12472.2714 (2018).

Hamidifar, H., Shahabi-Haghighi, S. M. B. & Chiew, Y. M. Collar performance in bridge pier scour with debris accumulation. Int. J. Sedim. Res. 37(3), 328–334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsrc.2021.10.002 (2022).

Hamidifar, H., Mohammad Ali Nezhadian, D. & Carnacina, I. Experimental study of debris-induced scour around a slotted bridge pier. Acta Geophys. 70(5), 2325–2339. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11600-021-00722-2 (2022).

Zanganeh-Inaloo, F., Hamidifar, H. & Oliveto, G. Local scour around riprap-protected bridge piers with debris accumulation. Iran. J. Sci. Technol. Trans. Civ. Eng. 47(4), 2393–2408. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40996-023-01034-9 (2023).

Mahdian Khalili, A., Akbari Dadamahalleh, P. & Hamidi, M. Experimental evaluation of dune formation downstream of pier scour hole with upstream debris accumulation. J. Hydraul. Struct. 10(1), 13–28. https://doi.org/10.22055/jhs.2024.45772.1281 (2024).

Raudkivi, A. J. & Ettema, R. Clear water scour at cylindrical piers. J. Hydraul. Eng. 109(3), 338–350. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9429(1983)109:3(338) (1983).

Chiew, Y. M. & Melville, B. W. Local scour around bridge piers. J. Hydraul. Res. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221688709499285 (1987).

Oliveto, G. & Hager, W. H. Temporal evolution of clear-water pier and abutment scour. J. Hydraul. Eng. 128(9), 811–820. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9429(2002)128:9(811) (2002).

Melville, B. W. Hadfield AC Use of sacrificial piles as pier scour countermeasures. J. Hydraul. Eng. 125(11), 1221–1224. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9429(1999)125:11(1221) (1999).

Kumar, V., Raju, K. G. R. & Vittal, N. Reduction of local scour around bridge piers using slots and collars. J. Hydraul. Eng. 125(12), 1302–1305. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9429(1999)125:12(1302) (1999).

Dias, A. J., Fael, C. S., & Núñez-González, F. Effect of debris on the local scour at bridge piers. in IOP conference series: materials science and engineering Vol. 471(2), 022024 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/471/2/022024.

Al-Jubouri, M., Ray, R. P. & Abbas, E. H. Advanced numerical simulation of scour around bridge piers: Effects of pier geometry and debris on scour depth. J. Marine Sci. Eng. 12(9), 1637. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse12091637 (2024).

Ebrahimi, M., Djordjević, S., Panici, D., Tabor, G., & Kripakaran, P. A method for evaluating local scour depth at bridge piers due to debris accumulation. in Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers-Bridge Engineering Vol. 173(2), 86–99 (Thomas Telford Ltd., 2020). https://doi.org/10.1680/jbren.19.00045.

Ebrahimi, M. et al. Experimental study on scour at a sharp-nose bridge pier with debris blockage. J. Hydraul. Eng. 144(12), 04018071. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)HY.1943-7900.0001516 (2018).

Al-Jubouri, M., Ray, R. P. & Al-Khafaji, M. S. Unraveling debris-enhanced local scour patterns around non-cylindrical bridge piers: experimental insights and innovative modeling. Sustainability 15(22), 159. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152215910 (2023).

Kandasamy, J. K. & Melville, B. W. Maximum local scour depth at bridge piers and abutments. J. Hydraul. Res. 36(2), 183–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221689809498632 (1998).

Raikar, R. V., & Dey, S. Scour of gravel beds at bridge piers and abutments. in Proceedings of the institution of civil engineers-water management Vol. 158(4), 157–162 (Thomas Telford Ltd, 2005). https://doi.org/10.1680/wama.2005.158.4.157.

Fakhimjoo, M. S., Ardeshir, A., Behzadian, K. & Karami, H. Experimental investigation and flow analysis of clear-water scour around pier and abutment in proximity. Water Sci. Eng. 16(1), 94–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wse.2022.12.001 (2023).

Funding

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.A. carried out the experiments, collected the data, and prepared the initial draft of the manuscript. M.R. and K.Q. conceptualized the study and supervised the overall progress of the project. Data analysis and contribution to the mechanistic interpretation were performed by Z.A., M.R., K.Q., M.M.A and M.R.M. The manuscript was critically reviewed and methodologically revised by M.R., K.Q., M.M.A., and M.R.M. All authors contributed to the writing and refinement of the final manuscript and approved its submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Consent for publication

The authors confirm that this work has not been published before, and its publication has been approved by all co-authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Abousaeidi, Z., Rahimpour, M., Qaderi, K. et al. New experimental configuration for investigation of debris accumulation effect on local scour at bridge pier and abutment. Sci Rep 16, 4261 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34364-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34364-x