Abstract

This paper presents the results of studies of the energy efficiency of an innovative implantable left ventricular assist device. One of the advantages of the proposed LVAD is in cases where end-stage left ventricular failure is accompanied by mitral valve regurgitation and pulmonary hypertension. Another advantage is minimally invasive implantation with minimal thoracic trauma, without disrupting the breathing process, which shortens the length of hospital stay. The best drive system for converting the rotary motion of the servo motor into reciprocating motion of the piston of the suction-discharge device was chosen. Two types of drive were considered, namely a yoke mechanism and a crank mechanism that were evaluated in terms of energy efficiency of the entire device. One of the most important conclusions is that both mechanisms have comparable operating parameters for balloon inflation and similar electrical energy consumption which amounts to comparable operating times for these mechanisms. However, the energy consumption of the yoke mechanism is slightly higher. At the same time the pressure in the left ventricle and aorta is slightly lower in comparison with a yoke mechanism. Furthermore, the results of the study also showed that the balloon pressures were significantly higher with crank drive, which may cause the balloons to wear out more quickly. The mass flow rates generated by both drives are similar with a slight advantage for the yoke mechanism. Finally, typical aortic, atrial and left ventricular pressure plots during the cardiac cycle are also shown.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Even despite the continuing development of pharmacological treatment, which can only slow down the process associated with advanced heart failure, heart transplantation is still the best option1. However, transplantation is not always feasible due to high mortality rates2 or lack of donors3. It is also important to bear in mind the large number of waiting patients4 and the high cost of the procedure5. One promising solution to these problems is a total artificial heart (TAH) that completely replace the diseased organ or ventricular assist devices that only support it. The process of developing both types of devices is not new and has been going on for decades6. Some examples include Imppella®, POLVAD7, Levitronix, CentriMag™, TandemHeart™, MicroMed DeBakey8, EXCOR® Berlin Heart, HeartMate 3™ and HeartWare™ (no longer on the market).

The general classification of such devices is based on their division into pulsatile flow pumps and continuous flow pumps. Interestingly, the former devices were dominant until 20099, while the later have been used almost exclusive since 201010. Pulsatile flow pumps, although they mimic the human heart well, are too heavy and large, making them not so portable. On the other hand, continuous flow pumps do not mimic the work of the human heart, but they are much smaller compared to their predecessors, which is of course related to patient mobility. However, it is important to bear in mind that small sizes are associated with significant rotational speeds, which can lead to thrombosis and haemolysis11,12, although the pump can be optimised in such a way as to reduce the rotational speed and thus the undesired phenomena such as haemolysis by reducing wall shear stresses caused by a reduciton of angular velocities while maximising pressure increases13. To the above list can be added a device to assist circulation in patients with end-stage heart failure14,15,16,17 that requires minimally invasive implantation. One of the advantages of the proposed device (pulsatile LVAD) in cases where end-stage left ventricular failure is accompanied by mitral valve regurgitation and pulmonary hypertension is that pulsatile flow in the left ventricle and aorta, and above all the absence of flow through the mitral valve during systole, is of great importance in the treatment of such conditions.

The main objective of the study was to select the best drive system for converting the rotary motion of the servo motor into reciprocating motion of the piston of the suction-discharge device of the above-mentioned innovative implantable left ventricular assist device (LVAD)14. Two drives providing reciprocating motion were selected for the study: the first with a yoke mechanism and the second with a crank mechanism. Both types of mechanisms are known in the literature and widely used, however, this does not apply to the blood pump industry. For example, a comparison of the two types of mechanisms is described in18, where feasibility of scotch yoke is studied rather than crank and slider mechanism. Some information on a modified yoke mechanism with a linear spring to the output slider is presented in19. The authors show that after cancellation of inertial effects the input torque due to friction in joints becomes constant, which makes it easier to control the entire mechanism. Another novel modification of such a drive is described in20, where the novel transmission mechanism is proposed to deal with problem associated with the reliance on resonance and the high expenses related to the large device dimensions. Yet another wave energy harvesting technique using the scotch yoke mechanism was proposed in21. In addition, a piezoelectric-electromagnetic hybrid wave energy harvester based on a scotch yoke mechanism is described in22. Furthermore, the contact problem of the scotch yoke mechanism was investigated in23 under elastohydrodynamic lubrication conditions, where some non-Newtonian behaviour of the lubricating oil was taken into account and extremely thin film thickness levels were predicted. Examples of the use of crank drive to cyclic change gas volume in a Stirling engine are discussed in24,25.

As can be seen, the application of both types of mechanisms is quite broad, but it is nevertheless difficult to find information in the available literature on how these mechanisms work when applied to drive the suction-discharge device used in an innovative left ventricular assist device. Both drives were evaluated here in terms of energy efficiency of the entire system. Various parameters in the pneumatic and hydraulic systems were also studied. The second important aspect was to obtain information on how long the various systems can run on charged batteries depending on the frequency of inflating and deflating balloons located in the heart model. The balloons in question here have a much more complex design compared to intra-aortic balloons. The former are described later in this article and the latter are described briefly e.g. in26.

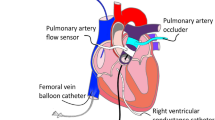

The innovative LVAD

The principle of operation of the device is illustrated in Fig. 1a and 1b. These figures show the geometry of the left ventricle at different stages in the cardiac cycle (systole and diastole). At the beginning of diastole, both balloons (valve (1) and ventricular (2) in Fig. 1a) are deflated. The valve balloon (1) is positioned in the lumen of the leaking mitral valve (3), which it replaces. Blood from the pulmonary vein (10) enters the left ventricle (5) via the atrium (6). It is also worth noting that the four main pulmonary veins are replaced by a single conduit (10) in the heart model. There is a mechanical counterpart in the hydraulic system in place of the aortic valve (8). This counterpart (artificial mechanical valve) is closed at the beginning of the diastole. At the end of the diastole, the valve balloon (1) is inflated with helium through a pneumatic line (9) to occlude the leaking mitral valve. In this way, blood flow from the atrium is stopped, which also prevents blood backflow to the lungs. In the next stage of the cardiac cycle (start of systole), the ventricular balloon (2) is inflated, which occurs shortly after the valve balloon (1) is inflated. This causes an increase in pressure \(p_v\) in the left ventricle (5). The consequence of the increased pressure is the opening of the mechanical aortic valve (8) and the ejection of blood into the aorta (4). This is followed by the end of the systole and the beginning of the diastole, when the valve balloon (1) is opened by its deflation. This results in the opening of the mitral valve (3) and the simultaneous deflation of the ventricular balloon (2). The sequence and corresponding synchronicity of inflating and deflating the individual balloons is due to the fact that they differ significantly in size and the respective location and number of helium inlet holes. The difference in size between the balloons is clearly visible in Fig. 1b. Moreover, the two balloons are connected by a narrowing (7) that tightly encircles the pneumatic line (9). The shape of the balloons is chosen to correspond to the anatomy of the heart.

The cyclic inflation and deflation of the balloons is associated with a pulsatile flow, which is consistent with the work of the heart itself. Furthermore, the inflation and deflation of the balloons is synchronised with the natural cycle of the heart based on the processing of ECG signals. These signals are analysed by the ODROID computer and are used to initiate the inflation and deflation of the balloons by means of a suction-discharge device (described in the next paragraph) via a pneumatic line (9).

Experimental studies

Experimental stand

To test the energy efficiency of the system for powering the left ventricular assist balloon assembly, a test stand was built as shown in Fig. 2. It mainly consists of two modules: an external portable device (case) and a device that simulates the operation of the circulatory system.

The circulatory system was equipped with a flexible heart model in which a set of balloons was placed: a ventricular balloon and a valve balloon. A valve balloon and a mechanical aortic valve (mechanical check valve) were used in the fluid flow line in order to ensure that the artificial blood was pumped using the work of the ventricular balloon. To ensure the flexibility of the heart muscle during the study, a flexible resin heart model was printed on a 3D printer (Fig. 3). A special transparent resin (Flexible 80A Formlabs) was used to print (Formlabs Form 3B 3D printer) the heart, which ensured that the ventricular and valve balloons could be observed. The patient’s CT data showing significant myocardial hypertrophy and LVEF (left ventricle ejection fraction) 17% were selected for printing16. The volume of the left ventricle was 315 cm\({}^3\), and that of the left atrium was 150 cm\({}^3\). The inlet (1) marks the point where fluid flows into the left atrium, while the outlet (3) marks the point where fluid flows out of the left ventricle. Also, at the bottom of the heart model the ventricular and valve balloon assembly (4) is attached.

A system that provides linear reciprocating motion should be used to drive the suction-discharge device. Highly dynamic electric linear actuators from companies such as Mitsubishi or LinMot can be used. In view of the need to accommodate this drive in a portable case, the Mitsubishi servo motors HG-KN13J were used because if its compactness. It is very important that the portable external suitcase with the battery-powered suction-discharged devices ensures the longest possible operation of the balloon set.

Two different drive assemblies of the suction-discharge device (Fig. 4) were prepared for the study to power a set of assist balloons. An assembly with a yoke mechanism and two guide rods was used to transfer power from the servo motor shaft to the compressor piston rod. The yoke mechanism is a mechanism in which the rotary motion of the crank is converted into reciprocating motion of the driven component. Finally, the second assembly prepared for testing to transfer power from the servo motor shaft to the compressor piston rod used a crank mechanism assembly.

These two drive units: the unit with the yoke mechanism and with two guide rods and the unit with the crank mechanism were tested for energy efficiency. The yoke unit tested (Fig. 5) is made up of the following components: crank, roller cooperating with the yoke, yoke, guide rods and linear guides.

Figure 6 shows the components of mechanisms converting rotary motion into reciprocating linear motion, made using traditional methods (machining) and by 3D printing. The use of 3D printing to fabricate the components allowed a significant reduction in the time to proceed with initial testing of the left ventricular assist device. Then, after testing the actuators with 3D printed components, some parts of the crank and yoke mechanisms were commissioned to be made from metal. Based on a number of tests, it was found that the 3D printed parts could withstand long-term operation just as well as those made of metal.

The drive assemblies with the suction-discharge device (Fig. 4) were the main part of the external portable case (Fig. 7). The case also contained: a meter (5) for measuring the electricity consumption of all electrical components of the external portable case (such as power, voltage, current), a meter (6) measuring the electricity consumption of the ODROID computer (ODROID XU4), 12/24V DC/DC converter to power the piston position sensor in the actuator and 12/5V DC/DC converter to provide 5V voltage to power the computer. Other elements include: a set of four batteries (7) connected in parallel (LI-ION 3s2p 12V, LP32700MJ1), a meter (8) measuring the energy consumption of a set of the Mitsubishi servo amplifier and Mitsubishi servo motor, a voltage converter (9) changing from 12/230V DC/AC, 12/24V DC/DC converter (10) to power the piston position sensor in the actuator to base the compressor system, ODROID computer (11).

Elements of the external portable case: (1)—suction-discharge device, (2)—yoke mechanism, (3)—mechanical gearbox 1/10 (Apex Dynamics AE050—yoke mechanism, SESAME PBE42-10—crank mechanism), (4)—Mitsubishi servo motor, (5)—meter for measuring the electricity consumption of all electrical components, (6)—meter measuring the electricity consumption of the ODROID computer and converters, (7)—batteries, (8)—meter measuring the energy consumption of the Mitsubishi servo amplifier and servo motor, (9)—voltage converter, (10)—12/24V DC/DC converter, (11)—ODROID computer.

Figure 8 shows the test stand for determining the battery power requirements (energy efficiency) of the servo motor and the components necessary for operation and control of the drive system. The tests carried out make it possible to diagnose the performance of the external LVAD. A hydraulic system pump in the form of a heart model with balloons inside pumps fluid through the hydraulic system components. Behind the heart model is a double-bladed mechanical check valve. This valve ensures that reverse flow is blocked when the ventricular balloon is deflated and fluid flows into the heart model. Compensating vessels simulating elastic human blood vessels are fitted to the system.

Pressure and temperature sensors were placed in the hydraulic (blood) and pneumatic system installation. Pressure sensors (ATM.1ST STS Sensor Technik Sirnach) allowed pressure to be measured at several locations in the hydraulic system installation, even in the left ventricle—ventricular pressure \(p_v\)—Spp and atrium \(p_{at}\) of the heart model. The helium pressure \(p_b\) in the pneumatic system close to the balloon assembly was measured with the SPAU-B2R sensor (Festo). In the hydraulic system, the flow rate was measured using an Optibatch 4011 C mass flow meter (Krohne). One of the components of the hydraulic system was also an electric heater, which enabled the temperature of the fluid in the system to be maintained to around \(36^\circ\)C. In addition, a temperature sensor placed in the artificial blood flow rate measuring device made it possible to determine the temperature of the liquid. The density of the liquid was also measured in the system.

The corresponding diagram in Fig. 9 shows the hydraulic, pneumatic and electrical systems of the test stand for testing the energy efficiency of the electrical system of an external portable case. The diagram shows: A1, A2—the tanks with a membrane to simulate the flexibility of the circulatory system, SpHe—helium pressure \(p_b\) sensor located in front of the set of balloons, Sp1—pulmonary veins pressure sensor, Sp3—aorta pressure \(p_{ao}\) sensor, Spp—atrium fluid pressure \(p_{at}\) sensor, Spk—fluid ventricular pressure \(p_v\) sensor, Q—mass flow meter, Z—fluid container, ZZ—mechanical check valve, NP—suction-discharge unit drive system, G1—a meter measuring the electricity consumption of all electrical components of the external portable case, G2—a meter measuring the energy consumption of a set of two Mitsubishi servo amplifier (MR-JE-10C) and Mitsubishi servo motor (HG-KN13J) components (measurement of power, voltage, alternating current), G3—a meter measuring the electricity consumption of the ODROID computer as well as 12/24V DC/DC converter and 12/5V DC/DC converter, PR1—converter Power Inverter LTC) from 12/230V DC/AC, PR2—12/5V DC/DC converter (YJ-240505X) to provide 5V voltage to power the ODROID computer, PR3—12/24V DC/DC converter (Elektroweb 1-W-022) to power the piston position sensor in the actuator to base the compressor system, C—ODROID computer, SeAm— Mitsubishi servo amplifier, Sa—a piston position sensor in the actuator to base the compressor system.

Test stand for energy efficiency study of the system for powering the left ventricular assist balloon assembly: (1)—flow reservoir replacing the pulmonary system, (2)—heart model, (3)—pulmonary veins pressure sensor, (4)—aorta pressure \(p_{ao}\) sensor, (5)—gas pressure \(p_b\) in the pneumatic system upstream of the balloon assembly, (6)—membrane tank, (7)—flow meter, (8)—external portable system with suction-discharge device (case), (9)—energy consumption meter for a set of Mitsubishi components, (10)—heater.

Diagram of the hydraulic, pneumatic and electrical system for testing the energy efficiency of the electrical system of an external portable case. A1, A2—the tanks with a membrane, SpHe—helium pressure \(p_b\) sensor, Sp1—pulmonary veins pressure sensor; Sp3—aorta pressure sensor \(p_{ao}\), Spp—atrium fluid pressure \(p_{at}\) sensor, Spk—fluid ventricular pressure \(p_v\) sensor, Q—mass flow meter, Z—fluid container, ZZ—mechanical check valve, NP—suction-discharge unit drive system, G1, G2, G3—meters measuring the electricity consumption, PR1, PR2, PR3—voltage converters, C—ODROID computer, SeAm—Mitsubishi servo amplifier, Sa—a piston position sensor.

From the measurements of energy consumption with meters G1, G2 and G3, it was possible to determine how long the electrical energy in the charged batteries was sufficient for and how the voltage on the batteries changed during the operation of the suction-discharge device. In the hydraulic system, the parameters of the circulatory system, i.e. the pressures in front of and behind \(p_{ao}\) the heart model, the pressures in the atrium \(p_{at}\) and left ventricle \(p_v\) of the heart model, as well as the flow rate, were measured and recorded. Tests of the left ventricular assist device were performed for balloon set operating frequencies of 40, 80, 120 and 160 cycles/min. The initial pressure \(p_b\) of the gas in the pneumatic system was approximately 75 to 90 mm Hg before proceeding to testing. The piston in the compressor was retracted.

Three portable external assemblies with suction-discharge devices (suitcases) were prepared for testing. The first drive unit with a yoke mechanism (Fig. 4) and with two guide rods, where a larger converter was used. The second drive unit differed from the first with a smaller converter. Finally, the third drive unit was equipped with a crank mechanism (Fig. 4) along with a smaller converter.

Measurement results and discussion

Testing of the energy efficiency of the drive unit with yoke mechanism began with an inverter 12/230V DC/AC of smaller dimensions and weighing approximately 0.22 kg. It was attached to the outside of the case due to the heat dissipation directly into the environment. The power source was four charged 3s2p 12V rechargeable batteries.

The smaller inverter allowed the system to achieve an operating time of up to 560 minutes at a balloon set operating frequency of 40 cycles/min. When the unit was operating at a frequency of 160 cycles/min, the stored energy in the batteries was sufficient for 150 minutes of operation. The intermediate operating times for 80 and 120 cycles/minute are shown in Fig. 10a. While the suction-discharge device was running, the electric batteries discharged and at around 10V the unit stopped working.

The use of a larger inverter in the electrical system, weighing approximately 0.55 kg, resulted in the system with the suction-discharge device only operating for approximately 300 minutes at 40 cycles/min. Furthermore, the increase in weight of the portable external case of 0.3 kg for the patient is significant. The twice shorter operating time and heavier weight of the inverter led to this solution being rejected in further studies.

The second drive unit of the external drive is the crank mechanism. This mechanism was fitted with 3D printed components and roller bearings. This time of operation, which is shown in Fig. 10b, was approximately 600 minutes for an operating frequency of 40 cycles/min and 175 minutes for 160 cycles/min. The use of the crank mechanism gave very similar results compared to the yoke mechanism. The operating time is minimally longer, especially for the lower values of the operating frequency of the suction-discharge device.

During the tests, several series of measurements were taken of the external portable device equipped with a yoke mechanism to determine the power P consumed by the electrical components of the case. To be sure of the test results, the tests of the assembly lasted for many hours. As can be seen from the characteristics shown in Fig. 11a, the power consumed by the components depends on the operating frequency of the suction-discharge device. The power consumed by all the components, depending on the measurement series, was between lines P1(1) and P1(2). The maximum power consumed by a set of two Mitsubishi components (amplifier and servo motor) can be described approximately by the relationship \(P_2 = 0.33 \,f + 1\) W or in more general form

where f is the operating frequency in \(\text {cycles}/\text {min}\), A is expressed in \(\text {W} \, \text {min} / \text {cycles}\) and B in W. In contrast, the maximum power consumed by all electrical components of the external portable case can be represented by the equation \(P_1 = 0.34 \,f + 14.5\) W. The power lost on the converter is in the range 5.5-8.5 W. The electrical power consumed by ODROID computer, 12/24V DC/DC and 12/5V DC/DC converters is approximately 6.4 W.

Analogous results for the crank mechanism are shown in Fig. 11b. This time, the maximum power consumed by the set of two Mitsubishi components can be described approximately by the relation \(P_2 = 0.32 \,f\) W and the maximum power consumed by all electrical components of the external portable case can be represented by the equation \(P_1 = 0.35 \,f + 10.5\) W.

Figure 12 shows the electricity consumption for the two mechanisms considered. The tests were carried out many times and the results are shown as maximum and minimum values. It can be seen from this plot that the electricity consumption with the yoke mechanism can be slightly higher than with the crank mechanism under the same operating conditions.

The flow rate \(\dot{m}\) in the circulatory (hydraulic) system is slightly higher with the yoke mechanism drive compared to the other drive (Fig. 13). For a frequency f of 160 cycles/min and an initial pressure \(p_b\) of 90 mm Hg in the pneumatic system with the compressor piston rod retracted, the flow rate using the yoke mechanism was 3.9 kg/min and for the crank mechanism it was 3.6 kg/min.

Pressure measurements show that, for the yoke mechanism, the pressure measured in the aorta \(p_{ao}\) (behind the heart model) for a ventricular and valve balloon inflation and deflation operating frequency of 80 cycles/min ranged from 32 to 113 mmHg (Fig. 14a). Measurements were made for an initial pressure \(p_b\) in the pneumatic system of 75 mmHg. For an initial pressure \(p_b\) of 90 mmHg, the differences were negligible, as the pressure \(p_{ao}\) ranged from 34 to 114 mmHg (Fig. 14c). For the crank mechanism, the measured pressure differences are slightly larger. Namely, for the case of an initial pressure \(p_b\) of 75 mmHg, we obtain a range from 28 to 115 mmHg (Fig. 14b), and for an initial pressure \(p_b\) of 90 mmHg: from 31 to 119 mmHg (Fig. 14d). Overall, in the aortic cases, the maximum pressure differences do not exceed 6 mmHg.

The situation is similar for the pressures \(p_v\) measured in the left ventricle. Thus, for a yoke mechanism and an initial pneumatic pressure \(p_b\) of 75 mmHg, the measurements show differences of -11 to 126 mmHg (Fig. 14a). For the crank mechanism, we obtain from -8 to 131 mmHg (Fig. 14b), again giving differences of no more than 5 mmHg. For an initial pressure \(p_b\) of 90 mmHg, we have corresponding pressures ranging from -12 to 127 mmHg for the yoke mechanism (Fig. 14c) and -8 to 134 for the crank mechanism (Fig. 14d). Thus, the maximum pressure differences do not exceed 8 mmHg depending on the type of mechanism and the initial pressure.

Larger differences in pressure measurements were recorded in the balloons \(p_b\). For an initial pneumatic pressure \(p_b\) of 75 mmHg, values ranging from -284 to 265 mmHg were obtained for the yoke mechanism (Fig. 14e) and from -283 to 314 mmHg for the crank drive (Fig. 14f), resulting in a 49 mmHg maximum pressure difference. For the case of an initial pressure \(p_b\) of 90 mmHg, pressures from -270 to 262 mmHg were obtained for the yoke mechanism (Fig. 14e) and from -270 to 324 mmHg for the crank mechanism (Fig. 14f), giving 62 mmHg of maximum pressure difference.

Conclusions

When testing the energy efficiency of the system for powering the left ventricular assist balloon assembly, two mechanisms were considered, namely yoke and crank. These mechanisms have comparable operating parameters for balloon inflation, fluid pumping in the hydraulic system and similar electrical energy consumption. It can be concluded that the operating times for these mechanisms are comparable. Electricity consumption with the yoke mechanism may be slightly higher than with the crank mechanism under the same operating conditions.

The pressure \(p_v\) in the left ventricle and aorta \(p_{ao}\) when using a crank mechanism is slightly higher than when using a yoke mechanism. However, the maximum pressure differences did not exceed 6 mmHg regardless of the initial pressure \(p_b\) in the pneumatic system. Significantly larger differences in measurements were observed for balloon pressures. For an initial system pressure \(p_b\) of 75 mmHg, the maximum differences were 49 mmHg and for an initial pressure \(p_b\) of 90 mmHg, even 62 mmHg. Larger pressure differences in the case of crank mechanism can lead to faster wear of the balloons. Equally importantly, higher balloon pressures \(p_b\) can make a difference when operating the drive system at high frequencies.

The device presented is intended to treat patients who have been incurable until now. Left ventricular failure is associated with mitral valve regurgitation in 50% of cases. The defect persists over time, causing an increase in pressure in the pulmonary circulation. Current drug therapy helps, but it also takes time, which is why we are dedicating this device to this group of patients with left ventricular failure and pulmonary hypertension.

The device is intended to provide support for several months also in home conditions. It should therefore be remembered that its purpose is to support circulation, not to replace it. There are no LVAD devices for this group of patients and the TAH devices available worldwide do not fill this gap. Despite the potential advantages, it is important to mention the limitations of the above studies, which may include:

-

The device requires further testing for thrombogenic potential.

-

The need for future in vivo validation is crucial.

-

Investigating a potential issue with ECG electrodes used to synchronise the LVAD with the natural heart, particularly when the LVAD is used at home. The simplest method is to read the recording from transcutaneous electrodes. This is a well-known, standardised method. However, it does not solve the problem of out-of-hospital treatment. One possible solution would be to place two electrodes inside the left ventricle, which, after signal cleaning, would transmit information to the drive. It should be mentioned that a simple QRST analysis is possible in a healthy heart. Patients with end-stage heart failure experience all possible arrhythmias, from atrial fibrillation to various types of conduction blocks. However, this problem has not yet been fully developed due to its complexity.

-

Improvement of a new polymer ensuring biocompatibility and tightness of the system during operation.

-

The tests were conducted on so-called artificial blood, which means that in order to obtain a liquid with the appropriate parameters, water was mixed with pharmaceutical glycerine.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Mancini, D. & Colombo, P. C. Left ventricular assist devices: A rapidly evolving alternative to transplant. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol.65(23), 2542–2555. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2015.04.039 (2015).

Roth, G. A. et al. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases and risk factors, 1990–2019: Update from the GBD 2019 study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol.76(25), 2982–3021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2020.11.010 (2020).

Quader, M. et al. Heart transplantation from donation after circulatory death donors: Present and future. J. Cardiac Surg.35(4), 875–885. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocs.14468 (2020).

Berk, Z. B. K. et al. Evaluation of in vitro hemolysis and platelet activation of a newly developed maglev LVAD and two clinically used LVADs with human blood. Artif. Organs43(9), 870–879. https://doi.org/10.1111/aor.13471 (2019).

Heidenreich, P. A. et al. Forecasting the impact of heart failure in the United States. A policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circ. Heart Failure6(3), 606–619. https://doi.org/10.1161/HHF.0b013e318291329a (2013).

Stewart, G. C. & Givertz, M. M. Mechanical circulatory support for advanced heart failure: Patients and technology in evolution. Circulation125(10), 1304–1315. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.060830 (2012).

Sarna, J., Kustosz, R., Major, R., Lackner, J. M. & Major, B. Polish artificial heart - New coatings, technology, diagnostics. Bull. Pol. Acad. Sci. Tech. Sci.58(2), 329–335. https://doi.org/10.2478/v10175-010-0031-5 (2010).

Noon, G. P., Morley, D., Irwin, S. & Benkowski, R. Development and clinical application of the MicroMed DeBakey VAD. Curr. Opin. Cardiol.15(3), 167–171. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001573-200005000-00008 (2000).

Teuteberg, J. J. et al. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Intermacs 2019 annual report: The changing landscape of devices and indications. Ann. Thorac. Surg.109, 649–660. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.athoracsur.2019.12.005 (2020).

Walther, C. P. et al. Implantable ventricular assist device use and outcomes in people with end-stage renal disease. J. Am. Heart Assoc.7(14). https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.118.008664 (2018).

Li, Y. et al. A new way to evaluate thrombotic risk in failure heart and ventricular assist devices. In Medicine in Novel Technology and Devices. Vol. 16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medntd.2022.100135 (2022).

Rogers, J. et al. Intrapericardial left ventricular assist device for advanced heart failure. N. Engl. J. Med.376, 451–460. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1602954 (2017).

Tesch, K. & Kaczorowska, K. The discrete-continuous, global optimisation of an axial flow blood pump. Flow Turbul. Combust.104, 777–793. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10494-019-00100-5 (2019).

PCT Application, Implantable left ventricular assist device and system for ventricular-assist for use in patients with end-stage heart failure PCT/PL2021/050004. https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=WO2021162564. Accessed 21 July 2025 (2025).

Tesch, K., Jasinski, R., Dabrowski, L. & Rogowski, J. Experimental investigation of the performance of an innovative implantable left ventricular assist device–Proof of concept. Appl. Sci.13, 973. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13020973 (2023).

Jasinski, R., Tesch, K., Dabrowski, L. & Rogowski, J. Innovative implantable left ventricular assist device-performance under various resistances and operating frequency conditions. Appl. Sci.13, 7785. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13137785 (2023).

Jasinski, R., Tesch, K., Dabrowski, L. & Rogowski, J. Effect of vascular lumen reduction on the performance and energy consumption of an innovative implantable LVAD. Appl. Sci.14, 284. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14010284 (2024).

Kumar, M. P., Akash, K. & Venkatesan, M. Scotch–Yoke mechanism for a syringe pump—A case study. 2016 IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 149, 012221. https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1757-899X/149/1/012221 (2016).

Arakelian, V., Le Baron, J-P. & Mkrtchyan, M. Design of Scotch yoke mechanisms with improved driving dynamics. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part K J. Multi-body Dyn. 230(4). https://doi.org/10.1177/1464419315614431 (2015).

Al Shami, E., Mayberry, L., Zhang, R. & Wang, X. A preliminary study of a novel wave energy converter of a scotch yoke mechanism-based power take-off. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess.60, 103533. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seta.2023.103533 (2023).

Hossain, M. Z. & Illias, H. A. Ocean wave energy harvesting via scotch yoke-based rotational generation. AIUB J. Sci. Eng.21(3), 167–175. https://doi.org/10.53799/ajse.v21i3.503 (2022).

Jia, S., Hong, C., Shi, G., Han, J., Xu, R., Xia, Y. & Xia, H. Scotch yoke structure inspired piezoelectric-electromagnetic hybrid harvester for wave energy harvesting. J. Intell. Mater. Syst. Struct. 35(20). https://doi.org/10.1177/1045389X241283121 (2024).

Al-Hamood, A., Jamali, H. U., Abdullah, O. I. & Senatore, A. Dynamics and lubrication analyses of scotch yoke mechanism. Int. J. Interact. Des. Manuf.13, 901–907. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12008-019-00545-y (2019).

Kropiwnicki, J. Analysis of start energy of stirling engine type alpha. Arch. Thermodyn.40(3), 243–259. https://doi.org/10.2478/ather.2019.130004 (2019).

Kropiwnicki, J. Application of stirling engine type alpha powered by the recovery energy on vessels. Pol. Maritime Res. 1(105) 27, 96–106. https://doi.org/10.2478/pomr-2020-0010 (2020).

Limbert, V. M. & Amiri, A. M. Intra-aortic balloon pump for patients with cardiac conditions: An update on available techniques and clinical applications. Reports 2(19). https://doi.org/10.3390/reports2030019 (2019).

Funding

This work was supported by the National Centre for Research and Development, Poland, POIR.01.01.01-00-1026/18.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RJ: conceptualisation; methodology; data curation; visualisation, investigation, validation. KT: conceptualisation; formal analysis; methodology; supervision; project administration; investigation; writing—original draft. LD: conceptualisation; methodology; data curation; visualisation, investigation. JR: conceptualisation; methodology; medical supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Institutional review board statement

This study was executed in strict accordance with the recommendations for Good Clinical Practice. The protocol was approved by the Independent Bioethical Committee with the permission number NNKBN 167/2017.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jasinski, R., Tesch, K., Dabrowski, L. et al. Study of the energy efficiency of various drive systems of an innovative implantable left ventricular assist device. Sci Rep 16, 4791 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34855-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34855-x