Abstract

Previous studies highlighting the pivotal function of the S100A8 protein have shown that inflammation and vascular endothelial harm play a major role in deep vein thrombosis (DVT) development, as evidenced by earlier studies highlighting the pivotal function of the S100 calcium-binding protein A8 (S100A8). Therefore, we aimed to establish a connection between S100A8 and DVT and investigate the role of S100A8 in DVT development. Blood specimens were taken from 23 patients with DVT and 31 controls. The fluctuation and association for S100A8 and interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β) in the specimens was assessed using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. We also used the human recombinant protein S100A8 to activate human umbilical vein endothelial cells and created a rat model to explore the possible relationship between them. Studies have shown that the infiltration of S100A8 sustains local inflammation and thrombus formation, which may exacerbate DVT by amplifying NLRP3/Caspase-1/IL-1β signals in the vascular endothelial cells.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT), characterized by atypical clogging of the deep vein affecting venous blood flow, is one of the prevalent peripheral vascular disorders1. Its occurrence is increased due to frequent events following major surgery or injuries, prolonged bedrest, limb fractures, progressive tumors, or pregnancy2,3. DVT often occurs in the deeper veins, such as those in the lower extremities or pelvic areas, where dislodged unstable blood clots may lead to pulmonary thromboembolism (PTE), which is often associated with a significant mortality rate. Every year, over 5 million people globally are affected by PTE4. Data reveals that untreated, persistent blood clots in patients with DVT result in approximately 0.3% of those with lower limb DVT experiencing post-thrombotic syndrome. This ailment leads to prolonged swelling and discomfort at the site of venous return blockage, greatly affecting life and employment and reducing daily activities and the ability to work. Therefore, stopping and reversing the progression of DVT are essential.

Notably, various immune components emitted by immune cells are vital in DVT development and progression. Therefore, examining immune indicators during DVT development might elucidate the fundamental mechanisms behind its onset or progression5. During the inflammatory response associated with DVT, immune cells migrate towards the endothelium, become activated, and release significant amounts of inflammatory substances. Furthermore, inflammatory agents are crucial in DVT development and progression6,7. Myeloid-related protein 8, the S100 calcium-binding protein A8 (S100A8), can create a hybrid form with S100A9. Preliminary research suggests that the S100A8/S100A9, primarily secreted by myeloid leukocytes in the blood, can adhere to living endothelial cells, stimulating the generation of diverse inflammatory compounds and prothrombotic reactions8,9,10. S100A9, derived from platelet cells, directly influences DVT by generating neutrophil extracellular traps and controlling venous thrombosis through its attachment to the CD36 receptor11,12. However, the exact molecular function of S100A8 in DVT development remains unclear.

Persistent inflammation-induced DVT hampers blood flow, with cell death and inflammation emerging as the main pathological elements13,14. Furthermore, within human thrombotic lesions, the damage or death of vascular endothelial cells is crucial in thrombi growth or progression15. However, this cell death is associated with apoptosis, necrosis, and pyroptosis16. Pyroptosis, a unique form of cellular death, originates from inflammatory vesicles and depends on activating caspase-1, resulting in the generation of Gasdermin D N-terminal (GSDMD-N) and the secretion of interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β)17. Localized cell death can result from the activation of various external factors, with studies connecting NLRP3-triggered cell death to damage to endothelial cells or thrombotic inflammation18, suggesting that focal death is crucial in venous thrombosis.

The complex relationship between blood clotting, endothelial cells, white blood cells, and inflammation is crucial in the onset of DVT6. Thrombosis is primarily due to dysfunction or harm to the endothelial cells19. Under typical health conditions, endothelial cells encounter complex signals and feedback systems to maintain fibrinolytic equilibrium in blood vessels20. However, during the inflammatory responses that occur in patients with DVT, white blood cells accumulate and release agents such as S100A8, disrupting regular vascular function and exacerbating DVT development6,21,22. Prior research has indicated increased S100A8 in the plasma, causing increased intercellular adhesion molecule 1 and β2 integrin Mac-1 levels in these cells and enhancing the adherence of vascular endothelial cells, contributing to DVT development23. Furthermore, recent studies show that IL-β1, a proinflammatory cytokine, induces oxidative stress and augments coagulation capacity in patients with DVT24,25. Therefore, these previous studies suggest a strong correlation between S100A8 and the primary onset of DVT. However, the specific association of S100A8 with DVT remains unclear.

Thus, in this study, we validated the increased concentrations of S100A8 protein and IL-1β in patients with DVT using clinical blood samples, and we examined how S100A8 induces endothelial cell dysfunction, which promotes DVT through the NOD-, LRR- and pyrin domain-containing protein 3 (NLRP3)/caspase-1/IL-1β pathway. We aimed to elucidate the essential link between S100A8 and IL-1β, illuminating the possible involvement of S100A8 in prothrombotic growth and providing new viewpoints on the evolution and treatment of DVT. Our results showed the intrinsic connection between S100A8 and IL-1β in endothelial cells and revealed S100A8’s role in prothrombotic progression.

Results

Basic details of clinical practice

Blood plasma specimens were examined from 31 individuals in the control group and 23 patients with DVT. Figure 1 shows each group’s attributes, comorbidities, and risk elements. There was no significant statistical difference between patients with DVT and the control group regarding age, sex, and body mass index (BMI) (P > 0.05; Fig. 1). In addition, we collected more detailed information on factors that may trigger the disease in patients (Document S1).

Basic details of clinical practice: The approximate information of the patients is listed in Fig. 1. Basic details of clinical practice, wherein the age, sex, and BMI of the patients are represented as mean ± SD, while the remaining items are expressed as the number of cases (proportion of the total sample). BMI, body mass index; SD, standard deviation.

The concentrations of S100A8 and IL-1β in human plasma

Compared with the control, the DVT group demonstrated significantly higher plasma concentrations of S100A8 (P < 0.001) and IL-1β (P < 0.001). Notably, both groups showed a significant positive correlation between the plasma levels of IL-1β and S100A8 (P < 0.001; Fig. 2).

Human plasma levels of S100A8 and IL-1β proteins and their correlation: (a) Compared with the control group, there was a significant increase in S100A8 plasma levels in the DVT group. (b) There was also a significant increase in the IL-1β blood levels in the DVT group. (c) A significant positive association was observed [ρ (rho) = 0.826, P < 0.001] between IL-1β and S100A8. ***Levels of significance include: P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05. DVT, deep venous thrombosis.

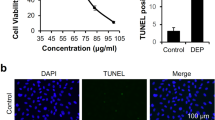

Levels of nuclear factor kappa B (RelA), NLRP3, caspase-1, IL-1β, and GSDMD RNA within human umbilical vein endothelial cells

Endothelial cell expression of nuclear factor kappa B [NF-kb] (RelA), NLRP3, caspase-1, GSDMD, and IL-1β RNA proportionally increased relative to S100A8 activation levels, differing from control groups. MCC950 did not significantly change the NF-kb (RelA) levels; however, it reduced the NLRP3, Caspase-1, GSDMD, and IL-1β levels in endothelial cells (Fig. 3). The primer data used in this experiment is presented in Document S2.

RNA levels of NF-kb(RelA), NLRP3, Caspase-1, GSDMD and IL-1beta in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) after intervention: (a) The 5 µg/mL and 10 µg/mL cohorts and the control group showed a significant difference in RelA RNA concentrations, whereas the discrepancy from the 2 µg/mL group was minimal. Furthermore, the S100A8 + MCC950 cohort exhibited notable fluctuations compared with the control group, unlike the 10 µg/mL cohort. (b) Significant differences were observed in NLRP3, caspase-1, and GSDMD RNA concentrations across all groups compared with the control group. Notably, a substantial gap in these differences was observed in the S100A8 + MCC950 group versus the 10 µg/mL group. (c) There was a significant variation in IL-1β RNA concentrations among the 5 µg/mL, 10 µg/mL, and S100A8 + MCC950 groups compared with the control. However, this difference was not significant in the 2 µg/mL group. Consequently, there was a significant difference between the S100A8 + MCC950 and 10 µg/mL groups. ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05, ns P > 0.05.

Levels of NF-kb (P65), NLRP3, caspase-1, IL-1β, and GSDMD in human umbilical vein endothelial cells

Elevated levels of NF-kb (P65), NLRP3, caspase-1, GSDMD-N, and IL-1β proteins were observed in endothelial cells, correlating with increased levels of S100A8 stimulation, compared with those in the control groups. MCC950 had minimal impact on NF-kb (P65) levels; however, it reduced the NLRP3, caspase-1, GSDMD-N, and IL-1β levels in endothelial cells (Fig. 4). The detailed data from the Western blot analysis is shown in Document S3.

Protein levels of NF-kb(p65), NLRP3, Caspase-1, GSDMD-N and IL-1beta in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) after intervention: (a) Notable differences were observed in the expression of NF-kb (P65), NLRP3, caspase-1, GSDMD-N, and IL-1β across the 2 µg/mL, 5 µg/mL, and 10 µg/mL groups compared with the control group. (b) Apart from the NF-kb (P65) expression, which revealed no significant variance between the S100A8 + MCC950 and 10 µg/mL group, other proteins exhibited notable differences in expression across the groups. (c) Significant differences were observed in NF-kb (P65) expression levels, whereas the expression of other proteins was not statistically significant compared with the control group. ***The statistical significance is noted as follows: P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05, nsP > 0.05.

Inflammatory cells and the S100A8 protein permeating DVT tissues

Upon examination, the extensive inferior vena cava (IVC) and thrombus tissue samples showed a dark red hue (Fig. 5a), with the DVT group displaying a higher mass-to-length ratio compared with the DVT + MCC950 group (P < 0.001; Fig. 5b). Unlike the control group, the DVT and DVT + MCC950 groups showed increased monocytes and lymphocytes within their lumen and vessel walls after thrombosis (Fig. 5d). The presence of S100A8 protein was significant in the DVT (P < 0.01) and DVT + MCC950 groups (P < 0.05) compared with the control group. However, there was no notable difference between the DVT group with the DVT + MCC950 group (P > 0.05; Fig. 5c and e). Additional information on haematoxylin & eosin (HE) staining and immunohistochemistry of animal specimens are presented in Document S4.

Mass-to-length ratio of thrombus tissue and the expression of inflammatory cells and S100A8 in the venous wall after MCC950 intervention in rats: (a) Tissue specimens from the DVT group showed a greater mass-to-length ratio than those from the MCC950 group. (b) Analysis of a vascular cross-section stained with haematoxylin and eosin, highlighting monocytes and several lymphocytes, revealed a thrombus buildup between the DVT and DVT + MCC950 groups. (c) The tissue samples underwent intense staining using S100A8. Compared with the control and DVT + MCC950 groups, the DVT group showed greater staining strength; however, the difference in staining intensity was not significant. DVT, deep venous thrombosis.

The expression of NLRP3 and IL-1β in DVT tissues

Notably, most of the NLRP3 and IL-1β regions that underwent staining and emphasizing were in the outer endothelial cells of the vein wall. Significant differences were observed in the NLRP3 and IL-1β concentrations across varied sample groups. In contrast to the DVT group, the MCC950 group demonstrated diminished NLRP3 activation, affecting IL-1β emission from endothelial cells (Fig. 6). The other immunofluorescence images are shown in Document S5.

The expression and correlation of NLRP3 and IL-1beta in the venous wall of rats after MCC950 intervention: (a) In vascular and thrombotic tissue areas, endothelial cells lining the veins exhibited elevated concentrations of NLRP3 and IL-1β. (b) The DVT group exhibited significantly higher levels of NLRP3 and IL-1β expression than the DVT + MCC950 group. Additionally, a notable correlation was observed between the stimulation of NLRP3 and the manifestation of IL-1β (ρ (rho) = 0.759; P < 0.001). ***Significance levels are P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05, nsP> 0.05. DVT, deep venous thrombosis; IL-1β, interleukin 1 beta.

Discussion

Venous thromboembolism occurs globally at an incidence of approximately 1 in 1,000, with approximately 250,000 new cases emerging yearly in China26,27. DVT is typically perceived as a condition impacting blood circulation, marked by a slow onset and potentially complex macrothrombotic disorders; however, it has an unclear pathogenesis19,28. Following a clinical evaluation of DVT, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) results showed a significant increase in the plasma levels of S100A8 and IL-1β proteins in patients9,29. Additionally, the onset and progression of DVT resulted in the penetration of inflammatory cells and S100A8 into areas of thrombosis. Therefore, our research indicates that plasma S100A8 triggers pyroptosis in endothelial cells and the manifestation and discharge of IL-1β in venous wall endothelial cells through the NLRP3/caspase-1/IL-1β pathway. Subsequent data support these results: Distinct concentrations of S100A8 and IL-1β were observed in the plasma of patients compared with controls, showing a strong correlation between these factors. Increased levels of NF-kb, NLRP3, caspase-1, IL-1β, and GSDMD in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were associated with the enhanced stimulation of the S100A8 protein. MCC950, specifically inhibiting NLRP3, may mitigate this association. With the onset and progression of DVT, the S100A8 secreted by various inflammatory cells penetrated rat venous thrombosis sites, accompanied by strong NLRP3 and IL-1β signals within the venous wall’s endothelial cells. Real-time polymerase chain reaction and Western blotting showed that the activation of the NLRP3/caspase-1/IL-1β pathway through the S100A8 recombinant protein in HUVECs initiated endothelial cell pyroptosis and resulted in IL-1β discharge.

Endothelial cells in the venous wall are vital connectors between blood components and venous tissues, and several studies suggest that endothelial dysfunction or harm caused by immune-inflammatory responses during venous thrombosis significantly contribute to DVT development6,30. Studies indicate that the activation of S100A8 can disrupt the endothelial barrier’s functionality by initiating the mitogen-activated protein kinase signalling pathway through the toll-like receptor and receptor for advanced glycation endproducts31. Moreover, Viemann et al. showed that the S100A8 protein induces cell death, resulting in extended damage to the stability of the endothelial cells. Harm to endothelial cells and the deterioration of the endothelial barrier amplify the local inflammatory response within blood vessels, leading to the discharge of several prothrombotic substances that intensify thrombosis32,33. Therefore, based on these findings, we explored the role of S100A8 in causing endothelial scorches in patients with DVT. We showed that HUVECs treated with recombinant S100A8 had increased levels of NF-kb, NLRP3, caspase-1, GSDMD-N, and IL-1β compared with the control groups, resulting in a closer arrangement of endothelium. In contrast, using MCC950, an NLRP3 inhibitor, significantly lowered the caspase-1, GSDMD-N, and IL-1β levels, reducing the venous thrombosis rate exacerbated by S100A8. This is consistent with the results reported by Chu et al. Their study and other previous studies34,35,36 suggest that DVT in cells could result from pyroptosis in endothelial cells and IL-1β release activated by S100A8.

Activating caspase-1 is vital for endothelial cell death, depending on a group of proteins known as inflammatory vesicles, with NLRP3 being the most significantly studied37,38. The activation of NLRP3 in endothelial cells initiates the conversion of pro-caspase-1 to its enzymatically active form, transforming and treating the cytokine until it matures and leads to cellular pyrokinesis in the presence of GSDMD39,40. Previous research has shown the crucial impact of NLRP3 activation in conditions associated with endothelial cell abnormalities, including diabetic retinopathy, atherosclerosis, and pulmonary hypertension41,42,43. However, the effects of NLRP3 on endothelial cells in patients with DVT have not been adequately studied. Therefore, we created a DVT model using IVC narrowing in Sprague-Dawley rats to mimic clinical thrombophilia44. Our results revealed a significant increase in S100A8, NLRP3, and IL-1β in sections of thrombosed vessels, and a reduced IL-1β expression when treated with MCC950.

In conclusion, clinical DVT cases exhibit a significant rise in human plasma S100A8 and IL-1β levels, as plasma S100A8 amplifies vascular endothelial pyroptosis by intensifying NLRP3/caspase-1/IL-1β pathway signals in venous endothelial cells and increasing their IL-1β production and secretion. A specific NLRP3 inhibitor effectively hinders S100A8 activation in endothelial cells, reduces caspase-1 stimulation, and diminishes IL-1β levels and release. Our results illuminate the intrinsic connection between S100A8 and IL-1β in endothelial cells, elucidating S100A8’s role in prothrombotic progression and confirming the infiltration of S100A8 sustains local inflammation and thrombus formation, which may lead to endothelial damage by amplifying NLRP3/Caspase-1/IL-1β signals in the vascular endothelial cells. it proposing new viewpoints on DVT management and development.

Limitations of the study

This study has some limitations. First, it was difficult to accurately identify the source of S100A8 in plasma. Additionally, S100A8 augments NF-kb in a concentration-dependent manner; however, how S100A8 impacts endothelial cells post NF-kb inhibition remains unclear. Therefore, the long-term prospects for vascular endothelial cells in rats with DVT were not explored.

STAR methods

Participants and comparison groups

The study recruited 23 patients with DVT and 31 controls to confirm or dismiss DVT based on the results of Doppler ultrasound and D-dimer examinations. Exclusion criteria included: (1) any other acute cardiac conditions; (2) autoimmune disorders; (3) any personal or familial history of venous thromboembolism; (4) previous use of anticoagulant-related drugs over the past 6 months; (5) instances of cancer; (6) being pregnant or after childbirth; (7) employing pacemakers; and (8) ongoing treatment with oestrogen or other hormonal medications. The study adhered to the Helsinki Declaration’s guidelines. Informed consent was obtained, and the study-related patient data and blood specimens underwent review and approval by the Hebei North College’s First Hospital Ethics Committee. Furthermore, to ensure the anonymity of participants, all blood specimens were redistributed and anonymized.

Human blood sample collection and enzyme-linked immunosorbent analysis (ELISA)

Patients fasted for 12 h (or throughout the night) before undergoing forearm venipuncture. Following collection, the collected blood was moved into tubes with sodium heparin anticoagulants and centrifuged at 3000 rpm at low speed for 10 min. Following the supernatant extraction, the patient’s plasma underwent protein analysis using the human S100A8 ELISA and IL-1β test kits (Shanghai Jining, 96T, China). Following the manufacturer’s instructions throughout the testing phase, the absorbance was measured with a wavelength set at 450 nm.

Cellular cultivation

Endothelial lineages derived from human umbilical veins (ZQ1099, Cellverse, China) were cultivated in Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium enriched with 10% bovine serum (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific), under conditions of 5% carbon dioxide and 37 °C in a moisture-regulated incubator. We used HUVEC broadcasts across between five and seven generations.

Activating HUVECs through the human recombinant S100A8 protein

HUVECs were divided into five separate categories using assorted induction methods: HUVECs, S100A8 at 2 µg/mL, S100A8 at 5 µg/mL, S100A8 at 10 µg/mL, and MCC950 at 10 µM. Throughout the intervention process, HUVECs had to be co-incubated with MCC950 (HY-12815 A; MedChemExpress, NJ, USA) for 2 h and then initiated using S100A8 (P00431; Solarbio, China). Following the cells’ induction, an ensuing treatment was administered 12 h later.

Separating RNA and performing reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

Complete RNA was isolated from HUVECs using the TRIZOL reagent (Invitrogen, CA, USA). Extracted RNA was converted into complementary DNA (cDNA) using a high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The initial strand of cDNA was amplified using the SYBR Green I incorporation method to evaluate the levels of messenger RNA (mRNA) expression using the ABI 7500 fast real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, USA). Following amplification, the 2−△△Ct method was used to determine comparative amounts of mRNA and the threshold cycle (Ct). Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase was used as the internal benchmark to normalize the data. Supplementary Table 2 details the sequences of primers used.

Western blotting technique

Proteins from all cell line groups were extracted using the radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (C1053; Applygen, China) combined with protease inhibitors (P1265; Applygen) and quantified through the bicinchoninic acid assay kit (P1511; Applygen). Furthermore, 20 µg of the protein was extracted and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane. The membranes were incubated with a range of antibodies, such as anti-RelA (K200045M; Solarbio, China), anti-NLRP3 (K010074P; Solarbio), anti-Caspase-1 (K001773P; Solarbio), anti-GSDMD-N (ab215203; Abcam, UK), and anti-IL-1β (3553-MSM7-P0; Thermo Fisher). Each membrane was kept overnight at 4 °C. The membranes were then treated with goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G secondary antibody (C31460100C; Thermo Fisher) and kept at 37 °C for 1–2 h. Targeted proteins were detected on PVDF membranes using an enhanced chemiluminescence kit (P0018S; Beyotime, China), and the blots obtained were recorded using a chemiluminescence apparatus (Clinx Science Instruments Co. Restricted, ChemiScope 6200, China) to capture blots.

Collecting rat venous thrombosis specimens

Each animal experiment was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Hebei North College and followed the guidelines of the animal Experiments Control and Supervision Committee. Furthermore, this study adheres to the recommendations of the ARRIVE guidelines (Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments; https://arriveguidelines.org). The research involved 7–8 week-old male Sprague Dawley rats sourced from Spefford (SCXK (Yu) 2020-0005, China). Each rat was housed in a pathogen-free indoor environment with controlled humidity, a temperature set at 24 ± 5 °C, and a cycle of 12 h of light and darkness. The rats had access to a clean diet and water. The animal research team had three cohorts, each comprising six individuals: the DVT model, the MCC950 + DVT model, and the control groups. The DVT group used an established model of blood flow restriction triggered using IVC binding. The rodents in the MCC950 + DVT cluster were administered an intraperitoneal dose of MCC950 (5 mg/mL/kg; HY-12815 A; MedChemExpress) some hours before undergoing IVC ligation. The control group rats did not undergo IVC ligation, and the rest of the procedure was similar to that used in the DVT model group. Notably, 48 h after developing the DVT stenosis model, the animals were euthanized by guillotine decapitation, tissue samples were collected from rats to measure IVC and thrombus lengths with a ruler, and their total weights were determined using a micro-weightier.

Utilizing haematoxylin and eosin staining, immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence methods on animal specimens

Rat IVCs were encased in paraffin, segmented into Sect. 5 μm thick, and stabilised with 4% paraformaldehyde, including thrombus tissue. Frequent histomorphological examinations were performed using haematoxylin and eosin staining methods. Tissue samples were subjected to immunostaining to identify S100A8 (K002925P; Solarbio) and CD31 (K010054M; Solarbio), targeting the detection of S100A8 invasion in endothelial cells. Immunofluorescence staining was used to ascertain whether endothelial cells displayed NLRP3 (K010074P; Solarbio) or IL-1β (3553-MSM7-P0; Thermo Fisher). After 1 h of permeabilisation with 0.6% Triton X-100, cells were stabilised in 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min, and subsequently covered with goat serum. Following an overnight incubation at 4 °C, the cells were subjected to additional incubation using anti-NLRP3 or IL-1β antibodies. This was followed by a 2-h incubation period at room temperature on a mixer with appropriate secondary antibodies. Consequently, diphenylindole was dispensed after staining for 20 min. The cells were photographed through a laser-scanning confocal microscope (model FV300, Olympus, Japan).

Statistical analysis

Every outcome was independently replicated at least three times. Within the correlation charts, dashed lines depict 95% confidence intervals, and the mean value, with a plus or minus sign variance, is presented. The two-tailed Student’s t-test was used for data comparison between two groups, with tests assessing equal variance and normal distribution. In cases wherein the data failed to satisfy the standards of equal variance or normality tests, the Mann–Whitney U-test, a nonparametric technique, was utilised. Furthermore, rank-centric one-way analysis of variance was used to perform multiple assessments, enhanced by applying the Bonferroni post hoc test. In cases where data failed to clear any of the tests, the Kruskal–Wallis nonparametric test, succeeded by the Dunn post hoc test, was utilised. Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS for Windows version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA, http://www.ibm.com/developerworks/spssdevcentral). A modification was applied to the ImageJ data to include the scanned images. Graphpad prism 9.0.0 (http://www.graphpad.com/updates/prism-900-release-notes) was used for graph plotting when a P-value < 0.05 threshold was deemed significant.

Data availability

Data are available for research purposes upon reasonable request to the corresponding author (MQ).

Materials availability

Materials from this study are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author (MQ). However, this study did not generate any new unique reagents.

References

Khan, F., Tritschler, T., Kahn, S. R. & Rodger, M. A. Venous thromboembolism. Lancet 398, 64–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32658-1 (2021).

Lutsey, P. L. & Zakai, N. A. Epidemiology and prevention of venous thromboembolism. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 20, 248–262. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41569-022-00787-6 (2023).

Anderson, F. A. Jr & Spencer, F. A. Risk factors for venous thromboembolism. Circulation 107 (Suppl 1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.0000078469.07362.E6 (2003).

Di Nisio, M., Van Es, N. & Büller, H. R. Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. Lancet 388, 3060–3073. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30514-1 (2016).

von Brühl, M. L. et al. Monocytes, neutrophils, and platelets cooperate to initiate and propagate venous thrombosis in mice in vivo. J. Exp. Med. 209, 819–835. https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20112322 (2012).

Budnik, I. & Brill, A. Immune factors in deep vein thrombosis initiation. Trends Immunol. 39, 610–623. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.it.2018.04.010 (2018).

Saghazadeh, A., Hafizi, S. & Rezaei, N. Inflammation in venous thromboembolism: Cause or consequence? Int. Immunopharmacol. 28, 655–665. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2015.07.044 (2015).

Gonzalez, L. L., Garrie, K. & Turner, M. D. Role of S100 proteins in health and disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell. Res. 1867, 118677. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbamcr.2020.118677 (2020).

Averill, M. M., Kerkhoff, C. & Bornfeldt, K. E. S100A8 and S100A9 in cardiovascular biology and disease. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc Biol. 32, 223–229. https://doi.org/10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.236927 (2012).

Sreejit, G. et al. S100 family proteins in inflammation and beyond. Adv. Clin. Chem. 98, 173–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.acc.2020.02.006 (2020).

Wang, Y. et al. Platelet-derived S100 family member myeloid-related protein-14 regulates thrombosis. J. Clin. Invest. 124, 2160–2171. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI70966 (2014).

Wang, Y. et al. Myeloid-related protein-14 regulates deep vein thrombosis. JCI Insight. 2, e91356. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.91356 (2017).

Aue, G. et al. Inflammation, TNFα and endothelial dysfunction link lenalidomide to venous thrombosis in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Am. J. Hematol. 86, 835–840. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.22114 (2011).

Navarrete, S. et al. Pathophysiology of deep vein thrombosis. Clin. Exp. Med. 23, 645–654. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10238-022-00829-w (2023).

Ma, H. et al. Endothelial transferrin receptor 1 contributes to thrombogenesis through cascade ferroptosis. Redox Biol. 70, 103041. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2024.103041 (2024).

Yuan, J. & Ofengeim, D. A guide to cell death pathways. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 379–395. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41580-023-00689-6 (2024).

Kovacs, S. B. & Miao, E. A. Gasdermins: Effectors of pyroptosis. Trends Cell. Biol. 27, 673–684. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tcb.2017.05.005 (2017).

Yao, F. et al. HDAC11 promotes both NLRP3/caspase-1/GSDMD and caspase-3/GSDME pathways causing pyroptosis via ERG in vascular endothelial cells. Cell. Death Discov. 8, 112. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41420-022-00906-9 (2022).

Chang, J. C. Pathogenesis of two faces of DVT: New identity of venous thromboembolism as combined micro-macrothrombosis via unifying mechanism based on two-path unifying theory of hemostasis and two-activation theory of the endothelium. Life (Basel). 12, 220. https://doi.org/10.3390/life12020220 (2022).

Wu, C., Kim, P. Y., Swystun, L. L., Liaw, P. C. & Weitz, J. I. Activation of protein C and thrombin activable fibrinolysis inhibitor on cultured human endothelial cells. J. Thromb. Haemost. 14, 366–374. https://doi.org/10.1111/jth.13222 (2016).

Shantsila, E. & Lip, G. Y. The role of monocytes in thrombotic disorders. Insights from tissue factor, monocyte-platelet aggregates and novel mechanisms. Thromb. Haemost. 102, 916–924. https://doi.org/10.1160/TH09-01-0023 (2009).

Sreejit, G. et al. Neutrophil-derived S100A8/A9 amplify granulopoiesis after myocardial infarction. Circulation 141, 1080–1094. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.043833 (2020).

Ryckman, C., Vandal, K., Rouleau, P., Talbot, M. & Tessier, P. A. Proinflammatory activities of S100: Proteins S100A8, S100A9, and S100A8/A9 induce neutrophil chemotaxis and adhesion. J. Immunol. 170, 3233–3242. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.170.6.3233 (2003).

Bester, J., Matshailwe, C. & Pretorius, E. Simultaneous presence of hypercoagulation and increased clot lysis time due to IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-8. Cytokine 110, 237–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cyto.2018.01.007 (2018).

Fei, J. et al. TXNIP activates NLRP3/IL-1β and participate in inflammatory response and oxidative stress to promote deep venous thrombosis. Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood). 248, 1588–1597. https://doi.org/10.1177/15353702231191124 (2023).

Heit, J. A. Epidemiology of venous thromboembolism. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 12, 464–474. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrcardio.2015.83 (2015).

Cheuk, B. L., Cheung, G. C. & Cheng, S. W. Epidemiology of venous thromboembolism in a Chinese population. Br. J. Surg. 91, 424–428. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.4454 (2004).

Stone, J. et al. Deep vein thrombosis: Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and medical management. Cardiovasc. Diagn. Ther. 7 (Suppl 3), S276–S284. https://doi.org/10.21037/cdt.2017.09.01 (2017).

Cao, G., Zhou, H., Wang, D. & Xu, L. Knockdown of lncRNA XIST ameliorates IL-1β-induced apoptosis of HUVECs and change of tissue factor level via miR-103a-3p/HMGB1 axis in deep venous thrombosis by regulating the ROS/NF-κB signaling pathway. Cardiovasc. Ther. 2022, 6256384. (2022). https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/6256384

Henke, P. Endothelial cell-mmdiated venous thrombosis. Blood 140, 1459–1460. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2022017938 (2022).

Wang, L., Luo, H., Chen, X., Jiang, Y. & Huang, Q. Functional characterization of S100A8 and S100A9 in altering monolayer permeability of human umbilical endothelial cells. PLoS ONE. 9 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0090472 (2014). e90472.

Viemann, D. et al. Myeloid-related proteins 8 and 14 induce a specific inflammatory response in human microvascular endothelial cells. Blood 105, 2955–2962. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2004-07-2520 (2005).

Viemann, D. et al. MRP8/MRP14 impairs endothelial integrity and induces a caspase-dependent and -independent cell death program. Blood 109, 2453–2460. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2006-08-040444 (2007).

Zhang, Y. et al. Inflammasome activation promotes venous thrombosis through pyroptosis. Blood Adv. 5, 2619–2623. https://doi.org/10.1182/bloodadvances.2020003041 (2021).

Chu, C. et al. miR-513c-5p suppression aggravates pyroptosis of endothelial cell in deep venous thrombosis by promoting caspase-1. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 10, 838785. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2022.838785 (2022).

Zeng, W. et al. The selective NLRP3 inhibitor MCC950 hinders atherosclerosis development by attenuating inflammation and pyroptosis in macrophages. Sci. Rep. 11, 19305. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-98437-3 (2021).

Toldo, S. & Abbate, A. The role of the NLRP3 inflammasome and pyroptosis in cardiovascular diseases. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 21, 219–237. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41569-023-00946-3 (2024).

Huang, Y., Xu, W. & Zhou, R. NLRP3 inflammasome activation and cell death. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 18, 2114–2127. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41423-021-00740-6 (2021).

Shi, J. et al. Cleavage of GSDMD by inflammatory caspases determines pyroptotic cell death. Nature 526, 660–665. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature15514 (2015).

Wang, K. et al. Structural mechanism for GSDMD targeting by autoprocessed caspases in pyroptosis. Cell 180, 941–955e20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.002 (2020).

Kong, H., Zhao, H., Chen, T., Song, Y. & Cui, Y. Targeted P2X7/NLRP3 signaling pathway against inflammation, apoptosis, and pyroptosis of retinal endothelial cells in diabetic retinopathy. Cell. Death Dis. 13, 336. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-022-04786-w (2022).

Yalcinkaya, M. et al. BRCC3-mediated NLRP3 deubiquitylation promotes inflammasome activation and atherosclerosis in Tet2 clonal hematopoiesis. Circulation 148, 1764–1777. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.123.065344 (2023).

Villegas, L. R. et al. Superoxide dismutase mimetic, MnTE-2-PyP, attenuates chronic hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension, pulmonary vascular remodeling, and activation of the NALP3 inflammasome. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 18, 1753–1764. https://doi.org/10.1089/ars.2012.4799 (2013).

Liu, H. et al. Inferior vena cava stenosis-induced deep vein thrombosis is influenced by multiple factors in rats. Biomed. Pharmacother. 128, 110270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110270 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the approval of this study by the First Affiliated Hospital of Hebei North University, as well as the equipment support and technical guidance provided by the Central Laboratory of the First Affiliated Hospital of Hebei North University and the Animal Laboratory of Hebei North University.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ming Qu: Conceptualization (lead) and resources (equal). Junyu Chi: Writing-review and editing (lead); statistical analysis (lead); conceptualization (equal); formal analysis (equal); Qitao Wang and Zhen Wang: Investigation (lead); data collection (lead); conceptualization (equal). Wenjie Zeng and Yangyang Gao: data collection (lead) and investigation (equal). Xin Li, Wanpeng Wang and Jiali Wang: formal analysis (lead), drafting of the manuscript (equal), data collection (equal).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Study approval statement: The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Hebei North University (Approval No.K2020240; 2022/03/30). All participants have obtained informed consent and have signed the “Informed Consent Form for Clinical Specimens of the First Affiliated Hospital of Hebei North University” in written form. The animal studies adhered to Hebei North University’s animal Ethics Review guidelines (Approval No.HBNU2023012006; 2023/03/06). Furthermore, this research complies with the ARRIVE guidelines (https://arriveguidelines.org) for documenting animal experiments, ensuring all experimental methods adhere to local legal and ethical norms.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chi, J., Wang, Q., Wang, Z. et al. S100 calcium-binding protein A8 exacerbates deep vein thrombosis in vascular endothelial cells. Sci Rep 15, 831 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85322-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85322-6