Abstract

Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae (Xoo) is a bacterial pathogen responsible for bacterial leaf blight (BLB) in rice, which can result in significant yield losses of up to 70%. A study evaluated the spread of Xoo in rice fields using environmental samples and employed colorimetric loop-mediated amplification (cLAMP) and PCR for detection. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) was used to measure infection levels. The research compared infection severity between a susceptible rice variety, Phitsanulok 2 (PSL2), and a resistant variety, PSL2-Xa21. Results showed that Xoo infection decreased from the leaves to the roots, but the bacteria persisted in soil and water for up to 12 and 6 weeks, respectively. The cLAMP assay, with the LpXoo4009 primer, effectively detected Xoo at low concentrations in both soil and water. Additionally, common grasses found in rice fields, such as Eriochloa procera, Echinochloa crus-galli and Chloris barbata were identified as temporary reservoirs for Xoo, facilitating its spread. The Xoo pathogen is distributed from infected leaves to roots and then from roots to the soil and nearby water. Grasses in the fields contribute to the perpetuation of the infection cycle serving as potential reservoirs that maintain the pathogen’s presence in the environment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae (Xoo) is a gram-negative bacterium causing bacterial leaf blight (BLB) in rice (Oryza sativa L.), significantly impacting global production of this vital crop and leading to yield losses of up to 70%1,2. The symptoms manifest on the leaves of young plants as pale green to grey-green, water-soaked streaks near the leaf tips and margins3. Xoo transmission in rice occurs in different ways such as through water, soil, grass weeds and rice seed4,5,6.

However, solid evidence to explain the distribution routes of Xoo in various parts of rice is lacking. Several studies demonstrated that rice pathogens spread and infected water, soil, and grass in rice field surrounding areas1,7. Nino-Liu et al.8 suggested that during periods of new cultivation, the rice field environment acted as a host for Xoo infection. Grain straw and various grasses found in rice fields such as yonghu grass (Lepthloa chinensis), water shrub grass (Zizania latifolia), cut grass rice (Leersia oryzoides), and pork chestnut grass (Cyperus rotundus) have been examined as potential habitats for Xoo9,10,11.

Molecular techniques are now extensively employed for accurate detection of pathogens causing this disease in rice such as the polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR–RFLP) technique12. The multiplex polymerase chain reaction (mPCR) technique has also been used for the simultaneous detection of multiple pathogens in the same reaction including Xoo and Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzicola (Xoc)13. Xoo detection by real-time PCR (RT-PCR) was developed to facilitate the simultaneous detection of three important rice pathogens Xoo, Xoc, and Burkholderia glumae in infected rice seeds and leaves14. However, PCR has limitations because it requires a complex process with sophisticated equipment that is unsuitable for examining field samples13,15. Our recent study successfully established a colorimetric loop-mediated isothermal amplification (cLAMP) technique to detect Xoo in rice fields, enabling specificity, precision, speed, and ease of use under isothermal conditions with the temperature controlled at 60–65 °C using a heating block16. The LAMP technique can detect many plant disease pathogens including Xoo in rice17 and leaf spot disease (Xanthomonas fragariae) in strawberries18. The LAMP technique is now increasingly applied to accelerate plant pathogen detection17,18,19.

However, the distribution route of Xoo is poorly understood, and this study investigated the potential spread of Xoo in rice from infected leaves and Xoo exudation from rice to nearby environments including soil, water, and grasses by cLAMP, PCR, and quantitative PCR (qPCR). Understanding the movement patterns of Xoo in rice plants and their spread into the environment will allow accurate planning of management and prevention strategies against Xoo outbreaks, thereby effectively reducing rice yield losses.

Results

Xoo-responsive characteristics of rice varieties PSL2 and PSL2-Xa21

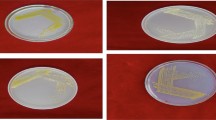

Two rice varieties, PSL2 and PSL2-Xa21, were used as models to examine the distribution and exudation of Xoo. Both varieties were inoculated at 55 days old with varying concentrations of Xoo: 2.5 × 101, 2.5 × 105, and 2.5 × 108 CFU/mL. Noticeable changes in morphology were observed at 14 and 28 DAI. PSL2 was more susceptible to Xoo compared to PSL2-Xa21, as evidenced by significant manifestations such as leaf rolling, wilting, and drying in PSL2 inoculated with Xoo at 2.5 × 101 CFU/mL, whereas PSL2-Xa21 inoculated with highest concentrations displayed only minor lesions of bacterial leaf blight (BLB), primarily confined to small lesions approximately 4 cm in lesion length caused by clipping (Fig. 1A and C). On examination at 28 DAI, PSL2 rice exhibited severe disease symptoms including rapid wilting and plant death at concentrations ranging from 2.5 × 101 to 2.5 × 108 CFU/mL, with average lesion lengths 10.41, 21.25, and 42.94 cm, respectively (Fig. 1C), whereas PSL2-Xa21 rice showed heightened leaf blight symptoms compared to day 14, although some healthy leaves with minimal disease severity were still evident. The average lesion length was two times shorter than PSL2 at 2.5 × 101 and 2.5 × 105 CFU/mL but three times at 2.5 × 108 CFU/mL (Fig. 1B and C).

Manifestation of lesions on rice leaves of PSL2 and PSL2-Xa21 varieties inoculated with Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae (Xoo). Rice leaves of PSL2 and PSL2-Xa21 varieties were inoculated by Xoo at different concentrations of 2.5 × 101, 2.5 × 105, and 2.5 × 108 CFU/mL and the negative control was inoculated with water (WC) by the clipping method. The control (CT) rice was unclipped. The lesion leaf appearance was observed at 14 DAI (A) and 28 DAI (B) and the results of the average lesion lengths on rice leaves for each concentration at 14 and 28 DAI (C).

Xoo distribution and exudation in rice by cLAMP, PCR and qPCR

To investigate the route of Xoo distribution and exudation from the Xoo-infected leaves, PSL2 and PSL2-Xa21 rice cultivars were inoculated with different concentrations of Xoo at 2.5 × 101, 2.5 × 105, and 2.5 × 108 CFU/mL. Various tissues including leaves, stems and roots were monitored. The water and rhizosphere soil were also tested for Xoo presence by cLAMP, PCR, and qPCR to determine whether Xoo was exudated from the root to the environment. Xoo was applied to the foliage of PSL2 and PSL2-Xa21 rice cultivars. At 14 and 28 DAI, our findings revealed the presence of Xoo infection in clipped leaves of both rice varieties at 14 DAI in all concentrations tested by PCR and cLAMP techniques. Examination of unclipped leaves encompassing older (unclipped-O), and newly emerged leaves (unclipped-N) post-inoculation, showed no evidence of Xoo infection throughout the 28 DAI period in both varieties. Subsequent assessment of Xoo infection in stems and roots of both rice varieties using PCR and cLAMP techniques at 14 DAI indicated infection in stems and roots at all concentration levels. Moreover, Xoo were detectable in soil and water samples from PSL2 rice in all concentrations starting from 14 DAI. However, in PSL2-Xa21 rice, Xoo were only detected in some soil and water samples subjected to high Xoo inoculation concentrations at 28 DAI (Fig. 2A and B).

Xoo distribution routes in rice plants and Xoo exudation to soil and water in PSL2 and PSL2-Xa21 rice varieties after 14 and 28 days of infection (14–28 DAI). The rice tissues used for Xoo detection included unclipped new leaves (Unclipped-N), unclipped old leaves (Unclipped-O), clipped leaves, stem, root, soil and water. Detection of Xoo infection by PCR technique (A) and cLAMP technique (B) analyzed by the amounts of bacteria in the samples using quantification PCR (qPCR) (C). Diagram of Xoo infection levels from rice leaves to environments nearby based on PCR, cLAMP, and qPCR techniques (D). The unclipped leaves were used as the control (CT) and the water-clipped leaves were used as the mock control (WC). The positive control (+) was genomic DNA of Xoo. Non-DNA template was used as negative control (NC) to determine whether the reaction was contaminated. The grouping of gels was cropped from different gels and their original images are in Supplementary Information 1.

Xoo quantitation in the studied samples above was also analyzed by qPCR using Xoo4009 primer. The pattern of the amount of Xoo infection corresponded to detection by the PCR and cLAMP methods. At 28 DAI in PSL2 rice varieties exposed to Xoo inoculation at all concentration levels, Xoo were detected in all parts of the rice plant (leaves, stems, roots) as well as in the soil and water of the experimental pots. The highest average quantity of Xoo, at 1.16 × 107 copies/μL, was found in the leaves of rice plants that received the highest level of Xoo inoculation, with bacterial quantities decreasing from leaves to roots. In water samples from the pot, the average quantity of Xoo was 1.47 × 101 copies/μL. Conversely, in PSL2-Xa21 rice varieties, Xoo were only detected in leaves that had received Xoo inoculation, while Xoo exudation into soil and water samples from rice plants exposed to high Xoo inoculation concentrations was restricted (Fig. 2C). Results suggested that following inoculation on rice leaves, Xoo tended to move from leaves to roots, with a likelihood of releasing Xoo from the roots into the surrounding soil and water near the infected rice plants (Fig. 2D).

Xoo persistence in soil and water

The study investigated the persistence of Xoo in both water and soil samples over time under controlled conditions. In water samples, the presence of Xoo was examined for 8 weeks post-inoculation. Within the first 1–2 weeks, Xoo were detectable at the lowest concentrations of 2.5 × 102 and 2.5 × 103 CFU/mL, respectively (Fig. 3A). Throughout weeks 3–4, Xoo persisted, despite the lowest concentration of 2.5 × 106–2.5 × 107 CFU/mL (Fig. 3A). However, by weeks 5–6, Xoo were only detectable at the lowest concentration of 2.5 × 108 CFU/mL (Fig. 3A). Eventually, during weeks 7–8, no Xoo were detected, indicated by a pH-induced color change in positive reactions (Fig. 3A). This indicated that the detectable concentration decreased over time, showing persistence for up to 6 weeks and the effectiveness of cLAMP in detecting Xoo in water samples.

Sensitivity of PCR and cLAMP techniques and evaluation of the persistence of Xoo in water and soil samples after inoculation for 8 weeks and 5 months, respectively. Assessment of the persistence of Xoo inoculation for 8 weeks at a concentration of 2.5 to 2.5 × 108 CFU/mL along with the negative control (NC) by PCR and cLAMP techniques using Xoo4009 and LpXoo4009 primers. (A), Xoo in soil samples following Xoo inoculation for 20 weeks at concentrations starting at 0.125 to 0.125 × 108 CFU/g and the negative control (NC) (B). The grouping of gels was cropped from different gels and their original images are in Supplementary Information 1.

Similarly, soil samples were prepared with varying Xoo concentrations and examined for the presence of Xoo over 20 weeks a period. Initially, during the first 1–2 weeks, Xoo were detectable at the lowest concentration of 0.125 × 103 CFU/g (Fig. 3B). However, over time, particularly in weeks 3–4, the minimum detectable concentration decreased to 0.125 × 105 CFU/g. At weeks 8 and 12, Xoo was still detected but at a limited concentration of 0.125 × 106 CFU/g (Fig. 3B). From 16 weeks onward, neither PCR nor cLAMP techniques detected Xoo in soil samples at any concentration level (Fig. 3B). Results exhibited a decline in detectable Xoo over time in soil samples, with persistence observed for up to 12 weeks.

Xoo-infectable grasses in paddy fields

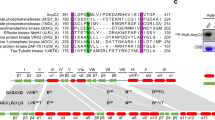

Based on the rbcL gene sequences, the grass species used in this study were identified as Eriochloa procera (Retz.) C.E.Hubb. (G1), Echinochloa crus-galli (L.) P.Beauv. (G2), Chloris barbata Sw. (G3), Bothriochloa decipiens (Hack.) C.E.Hubb. (G4), Echinochloa ugandensis Snowden & C.E.Hubb. (G5), Dinebra chinensis (L.) P.M.Peterson & N.Snow (G6), Cenchrus ciliaris L. (G7), Digitaria ciliaris (Retz.) Koeler (G8), Ischaemum rugosum Salisb. (G9). To assess as potentially serving as reservoirs of the pathogen of grass species commonly found in rice fields, the infectivity of Xoo was carried out. Symptoms of disease on grass leaves were observed at 7 DAI, exhibiting that the leaves of almost all grass species inoculated with Xoo exhibited symptoms of yellowing and drying, except for the leaves of Bothriochloa decipiens and Cenchrus ciliaris (Fig. 4A). The Xoo pathogen was examined using PCR and cLAMP techniques with Xoo4009 and LpXoo4009 primers, respectively and detected through a color change caused by pH alteration from pink to yellow (Fig. 4B). DNA amplification was confirmed by the LAMP technique using agarose gel electrophoresis (Fig. 4B). Conventional PCR used for Xoo detection in grass species also obtained ~ 302 bp-amplicon in seven species (Fig. 4B), except for G4 and G7 samples, possibly recognized as Bothriochloa decipiens and Cenchrus ciliaris. The phylogenetic relationships between the grasses were constructed to relate to Xoo infectivity. Results showed that seven grass species infected with Xoo including Eriochoa procara (G1), Echinochloa crus-galli (G2), Chloris barbata (G3), Echinochloa ugandensis (G5), Dinebra chinensis (G6), Digitaria ciliaris (G8), and Ischaemum rugosum (G9) were not sister clades but relatively dispersive (Fig. 4C). Bothriochloa ischaemum (G4) and Dactyloctenium aegyptium (G9) were closely related species in the same clade, with Bothriochloa decipiens (G4) tolerant to Xoo infection. Results suggested that Xoo infection did not correlate with the genetic proximity of grass and rice species.

Infectivity of Xoo in nine varieties of grass samples within rice fields by cLAMP and PCR, confirming the identification of grass species through grouping and genetic relationship analysis with Xoo infection using a phylogenetic tree. Characteristics of the leaves of nine species of grass samples and the leaves of rice used as the control (O. sativa) after seven days of inoculation (A). Increasing amounts of DNA from grass samples using the cLAMP using LpXoo4009 primer and PCR using Xoo4009 primer by changing the color of the solution inside the test tube of cLAMP and agarose gel electrophoresis of cLAMP and PCR (B). Relationships between Xoo infection and the phylogenetic tree of grasses and rice species of rbcL gene of grass samples (C). The grass species used in this study include Eriochoa procara (G1), Echinochloa crus-galli (G2), Chloris barbata (G3), B. ischaemum (G4), Echinochloa ugandensis (G5), Dinebra chinensis (G6), Cenchrus ciliaris (G7), Digitaria ciliaris (G8), Dactyloctenium aegyptium (G9) and Oryzae sativa (control). For PCR and LAMP assay, water was used instead of DNA template as the negative control (NC). Seven grass species were infected with Xoo (dark blue bars), while the other two non-infected grass species were represented as gray bars. The other grass species were not inoculated by Xoo as indicated by light blue bars. Their sequences were retrieved from GenBank for constructing the phylogenetic tree. The grouping of gels was cropped from different gels and their original images are in Supplementary Information 1.

Xoo distribution in Xoo-artificially inoculating rice field

Sampling of rice (leaves, stems, roots), soil, and water samples from the experimental rice field was conducted, followed by examination using the PCR and cLAMP techniques. Results showed no dispersion of Xoo in the tested rice leaves, soil, and water samples. Subsequently, Xoo was cultivated in the rice field when the rice plants were 55–60 days old. After three months of cultivation, samples were collected from the rice plants including unclipped and clipped leaves, rice seeds, stems, and roots as well as soil and water samples from around the area. Xoo was detected in four clipped leaf samples from six, rice seeds and stems were detected in five all positive, roots and soil samples tested positive for Xoo in three and one out of four samples, respectively while one water sample tested positive out of five samples (Table 1 and Supplemental Fig. 1). Nine months after infection, samples consisting of dried leaves, water and soil were examined for Xoo using the PCR and cLAMP techniques, with no Xoo detected (Table 1 and Supplemental Fig. 1). These findings indicated that the cLAMP technique detected Xoo in the environment three months after infection. Therefore, the inoculation of Xoo through rice leaves into the soil allows the pathogen to persist in the soil, as evidenced by Xoo detection in roots water and soil samples.

Discussion

Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae (Xoo) is a disease pathogen responsible for bacterial leaf blight (BLB) in rice, causing significant yield losses ranging from 20 to 50%20. Controlling and preventing BLB outbreaks is challenging because Xoo may remain latent or infect various environments including soil, water sources, and even grass weeds4. The disease can spread extensively to neighboring areas, leading to larger infections in rice fields14. Early detection of the pathogen, even before the symptoms appeared in rice plants, could effectively control and prevent disease spread, thus mitigating the epidemic impact17. Our recent study highlighted the effectiveness of cLAMP as a rapid, accurate, and resource-efficient method for detecting Xoo, potentially facilitating in-field testing16. In this study, a cLAMP approach was implemented to investigate the distribution of Xoo and explore whether the pathogen could travel from infected leaves and be exudated from roots into the soil and water in two rice varieties, as the susceptible rice PSL2 and the resistant variety PSL2-Xa21, as well as the potential infection of grass weeds commonly found in rice fields. Our findings demonstrated the movement of Xoo from infected leaves toward roots, with Xoo in roots released to the rhizosphere and subsequently to nearby water. Many grasses in the rice field were infected by Xoo as potential reservoirs for latent Xoo infection, thereby contributing to continued infection in subsequent rice crops.

In an artificial inoculation of Xoo to investigate the Xoo distribution and exudation in rice, two rice varieties, PSL2 and PSL2-Xa21, have been used as a model. PSL2 rice is widely grown in the lower northern region due to its high yield. However, it is susceptible to BLB caused by the Xoo pathogen, resulting in significant damage upon infection21. PSL2 has been bred to resist the Xoo infection by introgression of the Xa21 gene from IRBB21 rice variety as PSL2-Xa21. The PSL2 and PSL2-Xa21 rice varieties were inoculated with different concentrations of Xoo. Results showed that PSL2 rice exhibited more severe symptoms of BLB, including leaf rolling, drying, and rapid spread throughout the rice than the PSL2-Xa21 variety at 14 and 28 DAI. The PSL2-Xa21 rice at 28 DAI exhibited remarkably shorter lesion length compared to PSL2 rice. This indicated that PSL2-Xa21 had moderate resistance to Xoo. Xa21 is a disease resistance gene that encodes a receptor kinase-like protein derived from Oryza longistaminate22. Xa21 recognizes RaxX, a sulfated microbial peptide, mimicking the action of PSY (plant peptide containing sulfated tyrosine). However, PSY does not trigger the defense response of Xa21 like RaxX. Therefore, rice plants carrying the Xa21 gene can initiate a defense response against BLB23.

Both rice varieties were infected with Xoo via leaf clipping to study its pathogenesis. Samples from leaves, stems, roots, water, and soil were collected and analyzed using PCR, cLAMP, and qPCR to detect and quantify Xoo presence and distribution. Xoo was detectable in rice leaves, stems, roots, and in environmental sources including soil and water of both varieties. Xoo can invade and destroy plant cells, leading to internal infection in various rice tissues. Xoo infection in rice secretes RaxX, a sulfated microbial peptide, which can mimic the action of PSY receptor and other types of sulfated peptides such as phylosulfokine (PSK), root meristem growth factor (RGF), casparian strip integrity factor (CIF), and twisted seed1 (TWS1) located outside various plant cells, which play roles in various processes related to plant growth and development similar to PSY22. Therefore, RaxX can effectively bind to receptors before invading cells, allowing Xoo to damage cells in all parts of the rice plant23. Interestingly, unclipping leaves (unclipped-O) and newly emerging leaves after Xoo inoculation (unclipped-O) were absent for Xoo. It was postulated that Xoo traveled against gravity force via water flow in the xylem vessels8, similar to the pathogen Ralstonia solanacearum in tomato24. At 28 DAI, rice plants inoculated with Xoo showed leaf rolling and drying. Xoo formed plaques in the vascular systems that clogged the vessels, thereby impacting water transportation for the whole plant8. Further studies to explain this scenario need to be performed. Moreover, our findings showed that infecting Xoo on leaves led to Xoo release in rhizosphere soil and water in pots of both rice varieties. High Xoo amounts were detected in soil and water at high starting concentrations, while PLS2-Xa21 inoculated with low and moderate Xoo concentration did not release Xoo in water at 28 DAI. At 14 DAI, Xoo was not detected in soil and water, suggesting that Xa21 delayed BLB disease progression. The variation in Xoo detection in water by PCR, cLAMP, or qPCR was inconsistent. PCR and qPCR are more sensitive than cLAMP for DNA extraction from water contaminated with inhibitors25. In addition, at very low amount of starting DNA, stochastic effect influences the variation in DNA amplification due to random sampling of DNA molecules, leading to ambiguity of DNA amplification result. To mitigate this issue, we suggest two possible ways including increasing DNA input and performing technical replicates. Nevertheless, Xoo can be released from roots to the rhizosphere and subsequently into nearby water. Xoo can spread by water in rice fields or irrigation water, and dispersed by wind, rain, insects, or other means, leading to disease transmission to other rice plants or nearby areas8. Thus, preventing the exudation of Xoo from the roots of infected rice would control or halt Xoo outbreaks and reduce yield loss. PLS2-Xa21 exhibited moderate resistance to Xoo infection as a recommended variety in Xoo outbreak agricultural areas such as the lower northern part of Thailand.

Results suggested that Xoo may travel in rice plants down from the leaves to the roots, causing contamination in the surrounding environments through soil, water and grass weeds. However, this study had limitations (i) There was no solid evidence to confirm whether Xoo traveled via the vascular system, and (ii) it was not known whether the exudated Xoo were alive or dead and contributed to infection in rice plants. Further studies using suitable approaches are required to observe Xoo in the vascular system of rice under confocal microscopy via green fluorescence protein (GFP)-containing Xoo26 or to determine whether Xoo were alive or dead using PCR or qPCR via staining propodium monoazide (PMA)27,28.

Our findings showed that Xoo was exudated from infected rice to soil and nearby water. Two experiments were performed to determine: (i) the limit detection of cLAMP for Xoo detection in soil and water and (ii) how long Xoo could persist in soil and water under controlled laboratory conditions. The cLAMP assay showed a high ability to detect Xoo in soil and water. The lowest detected concentrations in soil and water samples were 0.125 × 103 CFU/g and 2.5 × 102 CFU/mL, respectively. The cLAMP assay was more sensitive than PCR. The cLAMP method relies on automatic cycling and robust DNA strand displacement occurring under constant temperature conditions. This process involves two main phases as an initial step and a subsequent combination of cycling amplification with elongation/recycling, while PCR requires three temperature steps. The cLAMP technique also reduces the risk of cross-contamination compared to other methods because it is checked by observing the color change from outside the tube by a dye sensitive to changes in pH in a single step16,29. Thus, there is no need to open the test tube to add additional dye. Xoo was detected as DNA remaining in soil for 12 weeks and in water for only 6 weeks, with minimal DNA concentrations detected at 0.125 × 106 CFU/g and 2.5 × 108 CFU/mL, respectively. The Xoo in the soil persisted longer than in the water because the soil contained substrates and essential minerals conducive to bacterial growth30,31. Xoo are aerobic and thrive longer in soil samples compared to water samples6. In this study, molecular approaches were used to detect the remaining Xoo DNA and not indicate the active Xoo. Further studies should investigate active Xoo in soil or water to reflect the capability of rice infection.

Grass weeds were also considered to be a potentially latent reservoir of Xoo. Numerous previous studies revealed that grass weeds such as Cyperus rotundus, Leptochloa chinensis, L. panacea, Leersia oryzoides, Zizania latifolia as well as additional host species like Cenchrus ciliaris, Cynodon dactylon, Cyperus difformis, Cyperus rotundus, Echinochloa crus-galli, Leersia hexandra, Leersia oryzoides, Megathyrsus maximus, Oryza longistamina, Paspalum scrobiculatum, Urochloa mutica, Zizania aquatica, Z. palustris, and Zoysia japonica can act as hosts for Xoo, surviving through winter in moist areas1,4,32,33,34. In this study, Xoo infection in grass weeds was conducted by collecting samples around Naresuan University, Phitsanulok, Thailand. Nine species of grass weeds were collected and identified based on morphological characteristics along with DNA barcode sequences from rbcL regions. Results showed that Xoo infected seven grass weed species including Eriochoa procara, Echinochloa crus-galli, Chloris barbata, Echinochloa ugandensis, Dinebra chinensis, Digitaria ciliaris, and Ischaemum rugosum but excluding Bothriochloa decipiens and Cenchrus ciliaris. A survey of grass weed species in rice fields in the northeastern region of Thailand covering 179 plots revealed common grass weed species such as Paspalum scrobiculatum L., Cynodon dactylon L., Panicum repens L., and Echinochloa colonum (L.)7. Mizukami and Wakimoto9, discovered that Xoo survived in the rhizosphere of grass weeds such as Leersia sp. and Zizania sp., as well as in the stem bases and roots of rice stubble. The wild grass, Leersia hexandra, can also be infected with different pathovars of X. oryzae, allowing a better understanding of the evolution of pathogenicity in rice agroecosystems11. Notably, grass species with Xoo infection were not grouped in a sister clade, indicating that Xoo infectability was independent of genetic relationships, and might involve the genetic variation of Xoo toward the adaptation to infect other grass species with Xoo susceptibility. However, pathogen interaction of Xoo with various hosts needs to be further investigated to better understand the underlying mechanisms of Xoo infection, and address Xoo outbreak control measures for sustainable development in rice agroecosystems. Xoo infection in these grass weeds demonstrated that the pathogen temporarily resided in rice weed populations, awaiting opportunities to re-infect rice fields. Therefore, weed control around rice fields can also mitigate the spread of BLB.

These results showed that Xoo was distributed from the infected leaves to the roots and then released into rhizophores in the soil and nearby water. To mimic the rice crop, rice in the field was inoculated by Xoo, and Xoo distribution was monitored as exudation after inoculation for over 9 months. Three months after Xoo inoculation, Xoo was detectable in rice seeds, leaves, stems, roots, soil, and water, consistent with the rice in controlled condition pots. However, in rice fields, it is possible to detect Xoo in soil and water because the ooze from the leaves drops into the water, contributing to contamination in water and soil nearby. Nine months after inoculation, Xoo was undetectable in soil, water and dried clipped leaves, consistent with the persistence in controlled soil, with Xoo DNA detected for up to 3 months. Our findings suggested that after harvesting, it is advisable to let the field lie fallow for at least 3 months to reduce the risk of reinfection and reduce soil and water sources of the pathogen as temporary reservoirs in the rice field before planting the next rice crop Destroying grass weeds would also help to reduce pathogen infection. Weeds in rice fields offer a temporary host for Xoo and Xoc,

Materials and methods

Bacterial culture of Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae

Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae (Xoo) strain SK2-3 isolated from Sukhothai province, Thailand35 was cultured using the streak plate technique on nutrient broth (NB) medium (peptone 10 g/L, beef extract 3 g/L, NaCl 5 g/L, and pH 7.0) under 28 °C for at least 72 h. The colonies were gathered to make the cell suspensions by dissolving in distilled water (Invitrogen, USA) and then adjusted to obtain optical density at 600 nm (OD600) as 0.2 and estimated for amount of bacterial colony at 2.5 × 108 CFU/mL36,37. The Xoo suspensions were freshly prepared before inoculation in rice and grasses to examine the Xoo infection and distribution.

DNA amplification by colorimetric LAMP (cLAMP), PCR and quantitative PCR (qPCR)

To detect the Xoo presence, a cLAMP assay containing a pH-sensitive indicator, phenol red, was conducted to monitor the pH solution drop by observing a change in color from pink to yellow resulting from DNA polymerization in the LAMP process releasing a proton into the solution29. The reaction was carried out according to our previous study16 consisting of 12.5 µL of WarmStart® colorimetric LAMP 2X Master mix (New England Biolabs, USA), 0.2 µM of each external primer (F3 and B3; Table 2), 0.8 µM of each internal primer (FIP and BIP; Table 2), and 2 µL of DNA template, and adjusted to 25 µL with UltraPure™ DNase/RNase-free distilled water (Invitrogen, USA). For every experiment, the Xoo4009 region-harboring plasmid (Supplemental Table 1) was used as the positive control and distilled sterile water was used instead of DNA as the negative control. The optimal temperature for the cLAMP assay was determined as 63 °C for 40 min in a MiniAmp Plus Thermal Cycler (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), heat block or water bath. The cLAMP results were visualized by directly changing the color of the reaction from pink to yellow for positive while the negative results exhibited the pink solution without the need for opening the test tube, thereby reducing the risk of contamination (carryover) of the LAMP product to the surrounding environment. The cLAMP product was subjected to 2% ethidium bromide-containing agarose gel electrophoresis and visualized under an ultraviolet (UV) transilluminator (Cleaver Scientific, USA).

Conventional PCR was also used to validate the results of cLAMP. A final volume of 25 µL consisted of 2X DreamTaq PCR Master mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), 0.2 µM of primer (Xoo4009F and Xoo4009R; Table 2), 20 ng of DNA template and adjusted to 25 µL with distilled sterile water. MiniAmp Plus Thermal Cycler (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) was used for the DNA amplification protocol with programmed temperature of DNA amplification consisting of pre-denature at 95 °C for 5 min, 35 cycles of denature at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 60 °C for 30 s and extension at 72 °C for 30 s, with a final extension at 72 °C for 7 min. The PCR products were subjected to 2% ethidium bromide-containing agarose gel electrophoresis and visualized under an ultraviolet (UV) transilluminator (Cleaver Scientific, USA).

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed to estimate the extent of Xoo infection in the specimens. Reactions were prepared using Xoo4009 primer38 at a final volume of 20 µL consisting of 2X Sensifast No-ROX solution (Bioline, USA), 0.2 µM of each primer (Table 2), 1 µL plant extract or 10 ng of DNA template and adjusted to 20 µL with distilled water. For DNA amplification protocol, CFX96 Touch Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad, USA) was used, with the temperature condition for DNA amplification pre-denature at 95 °C 5 min, 35 cycles of denature at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 60 °C for 30 s, and extension at 72 °C for 30 s. The melting curve analysis consisted of denaturation at 95 °C for 15 s, and then annealing at 60°C for 15 s for DNA duplexes to be randomly formed until reaching 95 °C. Fluorescence data were collected at every 0.2 °C and the fluorescent signal was captured for 10 s at each step of temperature increase. To quantitatively determine the amount of Xoo infection, a standard curve was created based on the serial 10-dilution of a Xoo4009-harboring plasmid concentration of 1.29 × 108 in a range of 0–1.29 × 108 copies/μL. The cycle threshold (Ct), obtained from amplification plots of different concentrations and logs of different concentrations, was performed using a linear regression model to obtain an equation that demonstrated the relationship between Ct and the log of the concentration (Supplemental Fig. 2). Then, the Ct values of the amplification plots obtained from different rice specimens were used to determine the amount of Xoo in terms of copy number based on the given equation of a standard curve. These calculated pathogen quantities for each sample were then utilized to generate a heat map using R software to demonstrate the pathogen quantities in each specimen.

Investigation of Xoo distribution in rice by artificial inoculation

Phitsanulok 2 (PSL2) and Phitsanulok 2 with the Xa21 gene (PSL2-Xa21) rice varieties were cultivated in experimental pots (22 cm × 24.5 cm (height x diameter)). Each pot was planted with three seedlings. The watering regimen was meticulously controlled until the rice plants reached 55 days. Subsequently, the rice plants were artificially infected by Xoo by the clipping method36,37. A Xoo suspension solution (OD600 = 0.2) was dissolved in distilled water at 2.5 × 108 CFU/mL and made into a tenfold dilution as 25 and 2.5 × 105 CFU/mL to clip the rice leaves at 15 leaves per pot. Sterile water was used for clipping in both PSL2 and PSL2-Xa21 as a mock. The control pots were unclipped rice leaves. Each treatment was performed in duplicate. To determine whether Xoo distribution passed from leaf to root and was exudated from root to soil and water in the pot, all rice pots were covered with plastic bags on the clipping day, and the water was added by directly pouring into the pot for 4 weeks to protect Xoo contamination from dropping out ooze from the leaves to water and soil directly (Fig. 5).

Treatments for artificial Xoo inoculation with various concentration of PSL2 and PSL2-Xa21 rice varieties by the clipping method. The PSL2 and PSL2-Xa21 varieties were inoculated with different Xoo concentrations of 2.5 × 101, 2.5 × 105 and 2.5 × 108 CFU/mL. The control treatments consisted of two types including unclipped control (CT) and leaves clipped by water (WC). Rice samples including leaves, stems, roots, soil and water were collected 14 days after infection (DAI) (A) and 28 DAI (B).

Various tissues from the rice plants were collected including unclipped rice leaves to assess the Xoo distribution by cLAMP, PCR, and qPCR. The tissues were divided into two types as old leaves that sprouted before inoculation (unclipped-O) and new leaves that sprouted after inoculation (unclipped-N), as well as clipped rice leaves, stems, and roots from both varieties at 14 and 28 days after infection (DAI) for two pots each (Fig. 5). Each specimen was used for DNA extraction following different approaches as described below.

The unclipped and clipped leaf samples at 14 DAI and 28 DAI were collected to measure the length of the lesions in centimeters from the clipping point to the end of the lesion (yellow area). In rice leaves showing symptoms of the disease, we cut the area under the lesion at 1 cm to obtain a leaf size of 1.5 × 1.5 cm. This was then cut into smaller pieces with clippers, placed in a 1.5 mL microcentrifuge test tube, and added with 100 µL of distilled water before mixing in a vortex for 2 min, keeping at room temperature for an hour, and then incubating at 95 °C for 30 min. After that, the sample was centrifuged at 8000×g for 5 min. The supernatant was aspirated and used as the DNA template for detecting Xoo by PCR, cLAMP, and qPCR techniques.

A Genomic DNA Isolation Kit (Plant) (GeneDireX, Taiwan) was used to obtain DNA from the rice stem and root for Xoo detection at 14 DAI and 28 DAI because the hard tissues enriched with polysaccharide from the secondary cell walls of the stem and root could interfere with the DNA amplification. Rice stem samples were cut at 2 cm above the root zone, 2 cm in length. The rice roots were cleaned with sterile water to remove soil and weighed at 2 g for DNA extraction. All specimens were thoroughly washed with distilled water before being finely ground using liquid nitrogen in a pestle and mortars. The fine powder was used for DNA isolation according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The quality and quantity of the extracted DNA were assessed using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer. The DNA obtained from these specimens was used as a template for Xoo detection by cLAMP, PCR and real-time PCR.

Xoo exudation from roots to soil and water and surrounding environments

Xoo exudation into the surrounding environment was also investigated. The rhizosphere soil was collected to isolate DNA and detect Xoo by cLAMP, PCR, and qPCR. The soil was weighed at 250 mg to isolate DNA using a DNasey®PowerSoil®Pro Kit (QIAGEN, Germany). The water in the rice pot of each treatment at 14 DAI and 28 DAI of both varieties was collected for 1.5 mL to isolate DNA and detect Xoo by cLAMP, PCR, and qPCR. This water was centrifuged at 8000×g for 1 min and the supernatant was aspirated into a new tube and centrifuged again at 10,000×g for 1 min. Then, the supernatant was removed, the sediment was aspirated into a new 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube with 50 μL of ddH2O and incubated at 95 °C for 30 min before performing DNA amplification. The DNA obtained from the soil and water was measured for quality and quantity using Nanodrop (Thermo Scientific, USA).

Determination of Xoo persistence in soil and water

A previous study demonstrated that Xoo existed in soil and water to promote soil and water-borne diseases. To test this hypothesis, we examined how long Xoo existed in soil and water under experimental conditions at ambient temperature. To determine Xoo persistence in soil, sterile soil samples (100 g) were placed in a container, and Xoo (5 mL) at different concentrations from 2.5 to 2.5 × 108 CFU/mL was inoculated at 1.25 CFU/g. Soil samples (250 mg) were collected at 1, 2, 3, 4, 12, 16, and 20 weeks. The DNA in the soil samples was isolated using a DNasey®PowerSoil®Pro Kit (QIAGEN, Germany). To determine Xoo persistence in water, 100 mL of sterile distilled water in a 250 mL-flask was mixed with 10 mL of various concentrations of Xoo at 2.5–2.5 × 108 CFU/mL. The Xoo-containing water was kept for 8 weeks at ambient temperature under experimental conditions. A 1.5 mL aliquot of water was collected every week to isolate DNA and detect Xoo presence. The collected water was centrifuged at 8000×g for 1 min, and then the supernatant was aspirated into a new tube and centrifuged again at 10,000×g for 1 min. The sediment was then aspirated into a new 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube with 50 μL ddH2O and incubated at 95 °C for 30 min before performing DNA amplification cLAMP and PCR were performed for Xoo detection in soil and water.

Evaluation of Xoo infection in grasses

Grasses found within and around the paddy field were collected from rice fields at Naresuan University, Phitsanulok, Thailand. Nine grass species were planted in pots and identified for species taxonomy based on morphological characteristics such as inflorescences, leaves, and stems (Supplemental Figs. 3 and Table 2). However, only morphology-aided species identification was insufficient. In this study, all species were subjected to DNA barcoding, ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase large subunit (rbcL) (forward: ATGTCACCACAAACAGAAAC, reverse: CTTCACAAGCAGCAGCTAGTTC, amplicon size 1362 bp)39. Three grass leaf samples of each species were collected for DNA extraction using a PureDireX plant extraction kit (GeneDireX, Taiwan) to amplify DNA barcodes by PCR, and all PCR products were sequenced by Sanger sequencing (Macrogen, Korea). All the DNA sequences obtained were analyzed for species identification by BLAST and deposited in GenBank (Supplemental Table 2). A phylogenetic tree was constructed by neighbor-joining using the MEGAX program to clarify the genetic relationships among rice and grass species.

The grass leaves were inoculated using the clipping method to examine the feasibility of Xoo infection by Xoo suspension at concentrations of 2.5 × 108 CFU/mL. Each species was clipped for 3–5 leaves. After Xoo inoculation, the grass leaves showed symptom development during 7 DAI. Three grass leaves were collected for each species. The leaves were cut 2 cm below the lesion to obtain 1.5 × 1.5 cm squares, and ground with liquid nitrogen. DNA extraction was conducted following the manufacturer’s instructions using a PureDirex plant extraction kit (GeneDireX, Taiwan). The DNA obtained was amplified by PCR and cLAMP techniques to detect Xoo presence. Grass species with Xoo infectable phenotypes were aligned with the phylogenetic tree of DNA barcodes to determine whether Xoo susceptible grass species had a genetic background.

Distribution of Xoo in artificially inoculated rice fields

The persistence of Xoo in the natural rice field environment was evaluated by collecting samples of rice plants (leaves, stems, and roots), soil, water, and grass, both before and at 3 and 9 months after Xoo inoculation. PSL2 rice varieties were planted at Wang Thong Rice Research Center, Phitsanulok Province in January 2022. The rice seedlings were transplanted in five rows, each containing 15 plants, spaced 25 × 25 cm apart. When rice growth reached 55 days, Xoo inoculation was performed using the clipping method38 with a bacterial concentration of 108 CFU/mL (in March 2022). Sampling involved collecting rice plant samples (leaves, stems, and roots), and soil samples from around the roots to track the path of Xoo from the rice roots, water samples, and grass samples within and around the rice field. The sampling area was divided into nine zones. The samples were collected 1 h before inoculation and at 3 and 9 months after inoculation in the same experimental area. Xoo were then detected using PCR and cLAMP techniques.

Data availability

Sequence data that support the findings of this study have been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) with accession numbers in Supplemental Table 2. Data is provided within supplementary information files which Supplemental Tables 1–2 and Figs. 1–3 are provided within Supplementary Information 2.

References

Mew, T. W. & Natural, M. P. Management of Xanthomonas Diseases 1st edn, 341–362 (Chapman and Hall, 1993).

Savary, S. et al. The global burden of pathogens and pests on major food crops. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 3(3), 430–439 (2019).

Ghasemie, E., Kazempour, M. & Padasht, F. Isolation and identification of Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae the causal agent of bacterial blight of rice in Iran. J. Plant Prot. Res. 48, 53–62 (2008).

Ou, S. H. Rice Diseases 2nd edn. (Commonwealth Mycological Institute, 1985).

Dilzahan, H. A. et al. Biocontrol of soil diseases and soil profile associated with rhizosphere of rice (Oryza sativa Subsp. Japonica) growing paddy fields in Kansai region, Japan. Acta Agric. Scand. B Soil Plant Sci. 70, 444–455 (2020).

Rahma, H., Rahman, E. & Marhamah, S. Diversity of endophytic fungi from shallots as a Fusarium oxysporum biological control agent. J. Biopest. 16, 115–123 (2023).

Tomita, S. et al. Differences in weed vegetation in response to cultivating methods and water conditions in rainfed paddy fields in north-east Thailand. Weed Biol. Manag. 3, 117–127 (2003).

Nino-Liu, D. O., Ronald, P. C. & Bogdanove, A. J. Xanthomonas oryzae pathovars: Model pathogens of a model crop. Mol. Plant Pathol. 7, 303–324 (2006).

Mizukami, T. & Wakimoto, S. Epidemiology and control of bacterial leaf blight of rice. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 7, 51–72 (1969).

Karim, R. S., Man, A. B. & Sahid, I. B. Weed problems and their management in rice fields of Malaysia: An overview. Weed Biol. Manag. 4, 177–186 (2004).

Lang, J. M. et al. A pathovar of Xanthomonas oryzae infecting wild grasses provides insight into the evolution of pathogenicity in rice agroecosystems. Front. Plant Sci. 10, 507 (2019).

Zhang, C. et al. PCR-RFLP identification of four Chinese soft-shelled turtle Pelodiscus sinensis strains using mitochondrial genes. Mitochondrial DNA 26, 538–543 (2015).

Cui, Z. et al. Multiplex PCR assay for simultaneous detection of six major bacterial pathogens of rice. J. Appl. Microbiol. 120, 1357–1367 (2016).

Lu, W. et al. Molecular detection of Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae, Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzicola, and Burkholderia glumae in infected rice seeds and leaves. J. Crop Prot. 2, 398–406 (2014).

Rigano, L. A., Marano, M. R., Castagnaro, A. P., Do Amaral, A. M. & Vojnov, A. A. Rapid and sensitive detection of citrus bacterial canker by loop-mediated isothermal amplification combined with simple visual evaluation methods. BMC Microbiol. 10, 1–8 (2010).

Buddhachat, K. et al. One-step colorimetric LAMP (cLAMP) assay for visual detection of Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae in rice. J. Crop Prot. 150, 105809 (2021).

Lang, J. M. et al. Sensitive detection of Xanthomonas oryzae pathovars oryzae and oryzicola by loop-mediated isothermal amplification. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 80, 4519–4530 (2014).

Bühlmann, A. et al. Erwinia amylovora loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) assay for rapid pathogen detection and on-site diagnosis of fire blight. J. Microbiol. Methods 92, 332–339 (2013).

Ruinelli, M. et al. Comparative genomics-informed design of two LAMP assays for detection of the kiwifruit pathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae and discrimination of isolates belonging to the pandemic biovar 3. Plant Pathol. 66, 140–149 (2017).

Yasmin, S. et al. Biocontrol of bacterial leaf blight of rice and profiling of secondary metabolites produced by rhizospheric Pseudomonas aeruginosa BRp3. Front. Microbiol. 8, 287562 (2017).

Kamhun, W., Pheng-Am, S., Uppananchai, T., Ratanasut, K. & Rungrat, T. Effects of nitrogen levels on sucrose content, disease severity of Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae and yield of hybrid rice (BC4F5). Agric. Nat. Resour. 56, 909–916 (2022).

Song, W. Y. et al. A receptor kinase-like protein encoded by the rice disease resistance gene, Xa21. Science 270, 1804–1806 (1995).

Ercoli, M. F. et al. Plant immunity: Rice XA21-mediated resistance to bacterial infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 119, 2121568119 (2022).

Khokhani, D., Lowe-Power, T. M., Tran, T. M. & Allen, C. A single regulator mediates strategic switching between attachment/spread and growth/virulence in the plant pathogen Ralstonia solanacearum. Mbio 8, 10–1128 (2017).

Nwe, M. K., Jangpromma, N. & Taemaitree, L. Evaluation of molecular inhibitors of loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP). Sci. Rep. 14, 5916 (2024).

Han, S. W., Park, C. J., Lee, S. W. & Ronald, P. C. An efficient method for visualization and growth of fluorescent Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae in planta. BMC Microbiol. 8, 1–9 (2008).

Nocker, A., Sossa-Fernandez, P., Burr, M. D. & Camper, A. K. Use of propidium monoazide for live/dead distinction in microbial ecology. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73(16), 5111–5117 (2007).

Joo, S., Park, P. & Park, S. Applicability of propidium monoazide (PMA) for discrimination between living and dead phytoplankton cells. PLoS ONE 14, e0218924 (2019).

Tanner, N. A., Zhang, Y. & Evans, T. C. Jr. Visual detection of isothermal nucleic acid amplification using pH-sensitive dyes. Biotechniques 58, 59–68 (2015).

Vega, N. W. O. A review on beneficial effects of rhizosphere bacteria on soil nutrient availability and plant nutrient uptake. Rev. Fac. Nac. Agron. Medellin 60, 3621–3643 (2007).

Foladori, P., Bruni, L. & Tamburini, S. Bacteria viability and decay in water and soil of vertical subsurface flow constructed wetlands. Ecol. Eng. 82, 49–56 (2015).

Li, Z. K. et al. A “defeated” rice resistance gene acts as a QTL against a virulent strain of Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae. Mol. Gen. Genet. 261, 58–63 (1999).

Reddy, A. P. K., Mackenzie, D. R., Rouse, D. I. & Rao, A. V. Relationship of bacterial leaf blight severity to grain yield of rice. Phytopathology 69, 967–969 (1979).

Valluvapridasan, V. & Mariappan, V. Alternate hosts of rice bacterial blight (BB) pathogen Xanthomonas campestris pv. oryzae. Int. Rice Res. New 14, 27–28 (1989).

Carpenter, S. C. et al. An xa5 resistance gene-breaking Indian strain of the rice bacterial blight pathogen Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae is nearly identical to a Thai strain. Front. Microbiol. 11, 579504 (2020).

Ke, Y., Hui, S. & Yuan, M. Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae inoculation and growth rate on rice by leaf clipping method. Bio-protocol 7, e2568–e2568 (2017).

Sagun, C. M., Grandmottet, F., Suachaowna, N., Sujipuli, K. & Ratanasut, K. Validation of suitable reference genes for normalization of quantitative reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction in rice infected by Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae. Plant Gene 21, 100217 (2020).

Lang, J. M. et al. Genomics-based diagnostic marker development for Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae and X. oryzae pv. oryzicola. Plant Dis. 94, 311–319 (2010).

Cameron, K. M. A comparison and combination of plastid atpB and rbcL gene sequences for inferring phylogenetic relationships within Orchidaceae. Aliso 22(1), 447–4642006 (2006).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Naresuan University (NU), Thailand and the National Science, Research and Innovation Fund (NSRF), Thailand under Grant Number R2566B027, with partial support from the Global and Frontier Research University Fund, Naresuan University, Thailand; Grant number R2566C051.

Funding

This research was supported by Naresuan University (NU), Thailand and the National Science, Research and Innovation Fund (NSRF), Thailand under grant number R2566B027, with partial support from the Global and Frontier Research University Fund, Naresuan University, Thailand; Grant Number R2566C051.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.B.: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing—original draft. O.R.: Investigation, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft. P.I.: Methodology. K. R.: Specimens, Project supervisor. K.S.: Specimens, Project supervisor. T. R.: Specimens for Xoo inoculation in rice field. All authors: Writing—review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ritbamrung, O., Inthima, P., Ratanasut, K. et al. Evaluating Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae (Xoo) infection dynamics in rice for distribution routes and environmental reservoirs by molecular approaches. Sci Rep 15, 1408 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85422-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85422-3

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Molecular and phenotypic diversity of bacterial leaf blight resistance in green super rice germplasm

BMC Plant Biology (2026)