Abstract

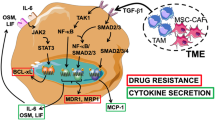

The emergence of targeted therapies for MET exon 14 (METex14) skipping mutations has significantly changed the treatment landscape for NSCLC and other solid tumors. The skipping of METex14 results in activating the MET-HGF pathway and promoting tumor cell proliferation, migration, and preventing apoptosis. Type Ib MET inhibitors, designed to selectively target the “DFG-in” conformation of MET, characteristically bind to the ATP-binding pocket of MET in a U-shaped conformation, extending into the solvent-accessible region and interact strongly with residue Y1230 through π-π interactions, have shown remarkable efficacy in treating METex14-altered NSCLC, including cases with brain metastases (BMs). Notably, vebreltinib and capmatinib have demonstrated superior blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeability in both computational and experimental models, highlighting their potential for treating the central nervous system (CNS) metastases. P-glycoprotein (P-gp) is highly expressed in the BBB, which limits the brain uptake of many highly lipophilic drugs. Despite challenges posed by P-gp mediated efflux, vebreltinib has emerged as a promising candidate for CNS treatment due to its favorable pharmacokinetic profile and minimal susceptibility to P-gp efflux. This study underscores the importance of molecular dynamics simulations in predicting drug efficacy and BBB penetration, providing valuable insights for the development of CNS-targeted metastases therapies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The mesenchymal epithelial transforming factor (MET) receptor tyrosine kinase and its variants are frequently implicated in a variety of solid tumors, notably gastrointestinal, head and neck tumors, and lung cancers. MET amplification or overexpression is not only seen in untreated patients, but also contributes to acquired resistance in metastatic EGFR-mutant non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). MET variation in NSCLC includes mutation, amplification, or gene fusion. Notably, MET exon 14 (METex14) skipping, occurring in 3–4% of NSCLC patients, is a significant MET aberration1,2.

Increased survival rates in NSCLC have unfortunately been accompanied by a rise in brain metastases (BMs), with over 30% of patients harboring MET alterations being at risk. These patients face a threefold higher mortality risk compared to those with wild-type MET3. The mechanism of BMs in NSCLC population is complicated. The metastatic cascade involves tumor cell shedding, hematogenous spread, penetration of the blood-brain barrier (BBB), and subsequent parenchymal colonization. While current therapeutic focus lies in managing established BMs, the potential of targeting tumor cells prior to visible metastasis formation represents a promising avenue. So far, METex14 skipping inhibitors have shown potential in this regard.

In March 2023, glumetinib4 was approved for marketing in China to treat adult patients with locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC harboring MET exon 14 skipping mutations. Notably, glumetinib demonstrated promising efficacy in treating brain metastases (BMs), achieving an 85% objective response rate (ORR) in 13 patients with METex14 NSCLC and baseline BMs5. This represents a significant advancement in the treatment of this challenging patient population. Subsequently, in November 2023, the National Medical Products Administration (NMPA) approved vebreltinib, a Class I innovative drug, for the treatment of locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC with MET exon 14 skipping mutations6. Vebreltinib demonstrated remarkable blood-brain barrier penetration, achieving a 100% ORR in patients with MET amplification and BMs7. In a groundbreaking development, vebreltinib received approval in April 2024 for treating IDH-mutant astrocytoma or glioblastoma with PTPRZ1-MET fusion genes8. This marks the second indication for vebreltinib in China and the first targeted therapy approved for treating patients with MET abnormalities in brain glioma.

MET tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) are broadly classified into type I, type II, and type III, with type I and type II being the predominant inhibitors with distinct binding mechanisms9. Type I MET inhibitors bind to the ATP-binding pocket in the “DFG-in” conformation of MET and are further divided into Ia and Ib subtypes. Type Ia inhibitors, such as crizotinib10, interact with the Y1230 residue, the hinge region, and the solvent front G1163. In contrast, type Ib inhibitors, including capmatinib11, tepotinib12, savolitinib13, glumetinib4 and vebreltinib6, exhibit strong interactions with the Y1230 residue and hinge region but lack interaction with G1163. Type II inhibitors, like cabozantinib14, merestinib15 and glesatinib16, bind the ATP-binding pocket in the inactive “DFG-out” state while extending into the hydrophobic allosteric pocket. Tivantinib is a type III inhibitor, which binds to allosteric sites distinct from the ATP binding site, and is reported to be non-ATP com petitive17. Notably, the recently approved type Ib inhibitors, glumetinib and vebreltinib, have demonstrated promising efficacy in treating advanced METex14 NSCLC. Furthermore, the success of vebreltinib in NSCLC patients with brain metastases and brain gliomas underscores its exceptional blood-brain barrier (BBB) penetration. This remarkable efficacy in the central nervous system (CNS) is attributed to the drug’s structural characteristics, including low molecular weight, high lipophilicity, and the ability to evade efflux by P-glycoprotein (P-gp)18.

This study focuses on five commercially available type Ib MET inhibitors (Fig. 1), comparing their binding modes, binding affinities, and blood-brain barrier penetration properties. We simulate their BBB penetration process and assess their potential as P-gp substrates, comprehensively evaluating the strengths of each drug. The insights gained from this analysis will inform the design of novel MET inhibitors with high selectivity and CNS permeability. Additionally, the developed drug permeability evaluation process can be applied to the development of other CNS-related drugs.

Methods

MD simulation of MET with drugs

In this study, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations19,20,21,22,23,24 were performed on five drugs and their complexes with MET. For tepotinib and capmatinib, crystal structures were available (PDB ID: 4R1V25 and 6SDE26, respectively). For the remaining drugs (vebreltinib, glumetinib, and savolitinib), complex structures were constructed using MOE-induced fit docking with 4R1V as a template, and missing residues 1150 and 1151 were patched using MOE27. All MD simulations were conducted using Amber22 with the GAFF228 and AMBER14SB29 force fields applied to the ligands and receptor, respectively. Ligand parameters were generated using the antechamber program with the AM1-BCC method30,31. Each complex was solvated in a cuboid TIP3P water box with periodic boundary conditions and neutralized with Na + or Cl- ions using tleap. Simulations employed the SHAKE algorithm32 to constrain bonds involving hydrogen atoms with a 2 fs time step, and electrostatic interactions were calculated using the Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) method33 with a 10.0 Å cutoff for long-range interactions. Prior to production runs, each complex underwent energy minimization with 10,000 steps of steepest descent followed by 10,000 steps of conjugate gradient. Subsequently, each system was gradually heated from 0 to 300 K in the NVT ensemble over 200 ps, followed by 1 ns equilibration in the NPT ensemble (300 K, 1 atm). Finally, 500 ns production MD simulations were performed in the NVT ensemble.

Construction of BBB mimetic bilayer

The CHARMM-GUI membrane builder34,35,36 was employed to construct a BBB mimetic bilayer using a four-component lipid model, balancing accuracy and computational resources. This model represents a consensus composition of human BBB membranes derived from reviews of human and porcine brain endothelial cells37, human and bovine brain endothelial cells, and brain capillary endothelial cells. The bilayer comprised 1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DMPC), 1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (DMPE), palmitoylsphingomyelin (PSM), and cholesterol (CHOL) in a 1:1:1:1 ratio, with 120 lipids and a 35 Å unilateral water layer thickness to ensure sufficient ligand movement. Counterions (K + or Cl-) were added to neutralize the system charge, along with 0.15 M KCl in the solvent, resulting in approximately 35,200 atoms per system.

PMF calculation

The CHARMM3638,39 force field was used for the bilayer, and drug topology parameters were generated using the CHARMM General Force Field (CGenFF) program40,41. Initially, energy minimization was performed for 1000 steps using the steepest descent method, followed by a 125 ps NVT simulation with solute constraints to relax the system. A 250 ps NPT simulation was then conducted at constant pressure (1 atm) and temperature (303 K) using the Berendsen coupling method42 for both. Lennard-Jones interactions were evaluated with a 1.2 nm cutoff, and the Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) scheme was employed for long-range electrostatics with periodic boundary conditions (PBC). All calculations were performed using GROMACS 202343,44.

Umbrella sampling was employed to calculate the free energy profiles. The drug was pulled from bulk water into the bilayer center along the z-axis, generating configurations with varying z-distances between the center of mass (COM) of the bilayer and the drug. A harmonic restraint with a force constant of 1000 kJ·mol⁻¹·nm⁻² and a pulling rate of 0.005 nm·ps⁻¹ were applied. Representative windows were selected with a COM spacing of 0.2 nm, spanning from the bilayer center to bulk water. Each simulation window, following a 1 ns equilibration, was run for 50 ns with a 2 fs time step. The COM z-distance between the bilayer and drug was maintained constant, and trajectories were saved every 50 ps. The weighted histogram analysis method (WHAM)45,46, implemented in GROMACS, was used to compute the free energy profile. Statistical errors were estimated using Bayesian bootstrap analysis with N = 50.

MD simulation of P-gp with drugs

A homology model of human P-gp was constructed based on crystal structure analysis and homology modeling, using the structure from 6QEX47 as a template. Missing residues 631–693 were modeled using SWISS-MODEL48. Subsequently, five drugs were individually docked into the P-gp substrate binding pocket using MOE induced fit docking to determine optimal binding conformations. For each drug, three poses were selected based on docking scores and visual inspection for further molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. All MD simulations were conducted using Amber22 with the GAFF228 and AMBER14SB29 force fields applied to the ligands and receptor, respectively. Ligand parameters were generated using the antechamber program with the AM1-BCC method30,31. Each complex was solvated in a cuboid TIP3P water box with periodic boundary conditions and neutralized with Na + or Cl− ions using tleap. Simulations employed the SHAKE algorithm32 to constrain bonds involving hydrogen atoms with a 2 fs time step, and electrostatic interactions were calculated using the Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) method33 with a 10.0 Å cutoff for long-range interactions. Prior to production runs, each complex underwent energy minimization with 10,000 steps of steepest descent followed by 10,000 steps of conjugate gradient. Subsequently, each system was gradually heated from 0 to 300 K in the NVT ensemble over 200 ps, followed by 1 ns equilibration in the NPT ensemble (300 K, 1 atm). Finally, 200 ns production MD simulations were performed in the NVT ensemble. The most stable trajectories were then analyzed for binding patterns.

MDCKII-MDR1 cell assay

The MDCKII-MDR1 cell model49 was used to assess drug permeability. Detailed experimental procedures are provided in the Supporting Information.

Results and discussion

Binding patterns of drug molecules with MET

Type Ib TKIs characteristically bind to the ATP-binding pocket of MET in a U-shaped conformation, extending into the solvent-accessible region alongside residues D1222, Y1230, and R1208. This conformation facilitates the formation of strong π − π stacking interactions with Y1230 of the A-loop, a key factor in the high selectivity of type Ib inhibitors.

To investigate the conformational dynamics of these inhibitors, we simulated the kinetics of five ligands in solution and analyzed the dihedral angle distribution of C3-C15-C1-N16 (using vebreltinib as an example) (Fig. 2). Dihedral angles between − 100° and 100° correspond to a U-shaped conformation, while angles outside this range indicate a more linear structure. Our results reveal that, with the exception of capmatinib, the distribution peak of dihedral angles for the other four drugs in solution favors the U-shaped state. Notably, vebreltinib’s distribution peak is closer to 0°, suggesting a more folded conformation that may facilitate entry into the ATP pocket. In contrast, capmatinib exhibits a broader dihedral angle distribution with a lower peak, indicating greater flexibility and a higher likelihood of transitioning between U-shaped and linear states, potentially hindering ATP pocket entry.

Binding patterns and key interactions between drug molecules and MET. Drug molecules are represented as colored sticks, key residues as white sticks. Hydrogen bond interactions are shown with yellow dashed lines, π-π interactions with green dashed lines, and hydrogen bond frequencies under dynamic are labeled on the graph.

All five drugs demonstrated strong MET binding affinity, with IC50 values below 10 nM4,6,50,51,52. To further elucidate their binding patterns and affinities, we constructed binding complexes and conducted long-term MD simulations. The simulations revealed stable binding modes for all five drugs (Fig. 3), consistently forming hydrogen bonds with the M1160 backbone amino group in the hinge region. Vebreltinib, savolitinib, glumetinib and capmatinib exhibited strong hydrogen bonds with M1160 via their 6 − 5 or 6–6 fused heterocyclic rings, with high frequencies of 91%, 96%, 99% and 97%, respectively. While tepotinib exhibited a slightly lower probability of hydrogen bonding with M1160 (84%), likely due to steric hindrance from its piperidine group protruding from the solvent front. Hydrogen bonds were also formed with D1222 in the DFG region on the right side. Notably, tepotinib demonstrated a higher probability of hydrogen bonding with D1222 (85%) compared to the other molecules, suggesting stronger binding due to the increased strength of N-O hydrogen bonds compared to N-N bonds. Additionally, π-π interactions with Y1230 played a crucial role in molecular stability, although this interaction was modulated by hydrogen bonding effects at D1222 and the stability of the terminal rotating region.

Interaction strength between drugs and residue Y1230 and its influencing factors. (A) Decomposed binding energy of Y1230, calculated by MM/GBSA. (B) The dihedral angle distribution of the rotatable bond significantly influences interaction with Y1230, where the four constituent atoms are depicted as spherical entities.

MM/GBSA analysis53, a common method for calculating small-molecule binding free energy, was employed to assess the binding affinity of the five drugs. Stable binding was observed for all five drugs, as evidenced by their binding free energies (Figure S1). Given the critical role of Y1230 in type Ib inhibitor binding, we focused our analysis on the specific contributions of Y1230 to ligand binding (Fig. 4A), the energy decomposition of the key residues M1160 and D1222 are shown in Figure S2. Free energy decomposition revealed that Y1230 contributed the most to vebreltinib binding, with a value of − 4.3 kcal/mol, double that of capmatinib. Since type Ib inhibitors typically extend into the solvent front, this region can influence ligand binding, particularly due to solvent effects and the presence of a rotatable bond that may affect the stability of the π-π interaction with Y1230. Analysis of the dihedral angle distribution of this rotatable bond during dynamics simulations (Fig. 4B) showed that vebreltinib and glumetinib have concentrated distributions near 0 degrees, indicating stable terminal structures with minimal rotation. This stability favors strong π-π interactions with Y1230, explaining the significant contribution of Y1230 to vebreltinib binding. However, the π-π interaction of glumetinib with Y1230 is weaker due to a lower probability (41%) of hydrogen bonding with D1222 in the DFG region. In contrast, capmatinib exhibited a broad dihedral angle distribution with a low peak, suggesting high flexibility and rotation of the terminal region, leading to weaker interactions with Y1230.

Type Ib MET inhibitors block MET activation by binding to ATP-binding sites in the MET kinase domain, thereby inhibiting the activation of the downstream MET signaling pathway. This inhibitory effect can reduce the proliferation, migration and invasion of tumor cells, thus producing an inhibitory effect on tumor growth. Therefore, we can improve the competitiveness with ATP to improve the drug efficacy. Our analysis of the interactions of five MET-targeting drugs and their solution conformations revealed that drugs favoring a U-shaped structure, particularly vebreltinib, have improved access to the ATP pocket. Further investigation of drug-target interactions showed that strong binding affinity is achieved through stable hydrogen bonding with the hinge region residue M1160 and π-π interactions with Y1230. Hydrogen bonding with D1222 and stability of the rotatable terminal structure are crucial for optimal interaction with Y1230, as a stabilized end region promotes stronger π-π interactions due to coplanar alignment with the drug’s ring moiety. Overall, our findings highlight the importance of considering both target binding and efficient binding pocket entry in the design of MET inhibitors.

Membrane permeation process analysis of drug molecules

For most drugs to reach their intended targets, they must first cross at least one cellular membrane. While high target affinity is essential for potency, poor membrane permeability can severely limit a drug’s efficacy in vivo. Drug transport across membranes primarily occurs through passive or active mechanisms. Active transport utilizes energy from processes such as ATP hydrolysis, whereas passive transport relies on simple diffusion without external energy input. The blood-brain barrier (BBB), formed by tight junctions between brain capillary endothelial cells, selectively restricts the passage of substances from the bloodstream into the brain. Overcoming this barrier poses a significant challenge in drug development, as it can greatly affect a compound’s ability to reach therapeutic targets within the central nervous system (CNS). Key physicochemical properties influencing membrane binding and diffusion include lipophilicity, molecular weight, and polarity. Lipinski’s Rule of 5, which employs four criteria (molecular weight ≤ 500 Da, octanol-water partition coefficient (logP) ≤ 5, ≤ 5 hydrogen bond donors, and ≤ 10 hydrogen bond acceptors), is often used to predict BBB permeability54.

Due to the critical importance of BBB penetration for CNS drugs, numerous strategies have been explored to enhance drug delivery across this barrier55,56,57. Computational methods offer several advantages over experimental approaches for predicting BBB permeability, including high throughput, low cost, and increased efficiency58. For instance, Siwy et al. employed all-atom replica-exchange umbrella sampling molecular dynamics simulations to investigate the partitioning of charged and neutral peptides into a BBB mimetic bilayer59. Liang et al. successfully predicted the BBB permeation of Erlotinib and JCN037 using molecular simulations, demonstrating good agreement with experimental results60.

The process of drugs passing across the BBB. (A) Free energy profiles of drugs passing across BBB based on the umbrella sampling dynamics, the x-coordinate is the distance of the drugs molecule from the center of the bilayer in the Z direction. Standard deviations from bootstrapping are shown in error bars. (B) Schematic diagram depicting drugs pass across the BBB (using vebreltinib as an example), with drug molecules shown as pink spheres, water solution as surface, and bilayer components (DMPC, DMPE, PSM, CHOL) as sticks in blue, green, pink, and orange, respectively.

In this study, we employed umbrella sampling to simulate the permeation process of five drugs across a BBB mimetic bilayer. Assuming symmetry in the transmembrane process, we focused solely on drug insertion into and movement towards the bilayer center (Fig. 5B). The convergence of umbrella sampling simulations is demonstrated in Figs. S3 and S4. Free energy profiles for BBB bilayer permeation were calculated using potential of mean force (PMF) analysis based on umbrella sampling, as shown in Fig. 5A. All five drugs exhibit significant energy barriers upon membrane entry, peaking at the bilayer center. However, vebreltinib and capmatinib demonstrate notably lower energy barriers within the membrane. Vebreltinib, in particular, displays an energy peak only 12.94 kcal/mol higher than that of the outer membrane, suggesting relatively facile membrane penetration. The flatter free energy profile of vebreltinib further supports this notion, suggesting enhanced BBB permeability. This observation aligns with the reported clinical efficacy of vebreltinib in treating brain metastases and gliomas. In contrast, savolitinib, glumetinib, and tepotinib encounter substantially higher energy barriers (> 25 kcal/mol), illustrating considerable difficulty in permeating the membrane.

Selected snapshots of drugs on the membrane surface and in the membrane center. The drugs are shown as sticks at about 25 Å z-distance from the center of the membrane and surface at about 0 Å z-distance from the center of the membrane. The bilayer is shown as lines with DMPC, DMPE, PSM, and CHOL in blue, green, pink and orange, respectively. The key lipids that interact with the drug on the membrane surface are shown as sticks, and the key hydrogen bond frequencies are labeled on the figure. The TPSA and LogP of drugs are calculated by MOE.

Notably, glumetinib exhibits an energy minimum at 25 Å from the membrane center, lower than in bulk solution (the green curve in Fig. 5A). Conformational analysis of all five molecules near this distance reveals close proximity to the membrane (Fig. 6). Specifically, glumetinib forms strong hydrogen bonds with the head amino group of DMPE with a 73% probability. This interaction, likely enhanced by glumetinib’s unique sulfone group, creates an energy trough near 25 Å. In contrast, the other four drugs exhibit weaker interactions with the membrane at this distance, suggesting that while glumetinib may readily associate with the membrane surface, this interaction could potentially hinder its transmembrane passage.

With the exception of vebreltinib, the remaining drugs also demonstrate a propensity for interaction with DMPE, highlighting the role of the charged amino group on DMPE in facilitating drug-membrane interactions. The hydrophobic nature of the membrane center makes molecular integration energetically costly. However, vebreltinib and capmatinib, with their relatively low topological polar surface area (TPSA), exhibit lower energies in the membrane center, translating to lower energy barriers for membrane integration and contributing to their favorable permeability profiles. Conversely, tepotinib, positively charged under neutral conditions, exhibits a low logP and a considerably higher energy requirement (approximately 35 kcal/mol) in the hydrophobic membrane center, making its transmembrane passage particularly challenging.

P-glycoprotein efflux analysis

The blood-brain barrier (BBB) is a selective barrier that protects the brain from potentially harmful substances while allowing essential nutrients to pass through. To penetrate this barrier effectively, drugs typically employ several key mechanisms, often leveraging the BBB’s unique structural features. Small, lipophilic molecules can cross the barrier via passive diffusion, taking advantage of the lipid-rich cell membranes, especially if they are neutral and under 400–500 Da. While many efflux transporters (like P-glycoprotein) work to remove drugs from the brain, drugs need to be designed to evade or inhibit these transporters, allowing higher concentrations to remain in the brain. P-glycoprotein (P-gp), encoded by the Multiple Drug Resistance 1 (MDR1) gene, is an important protein of the cell membrane that pumps xenobiotics out of cells. One critical active efflux mechanism is mediated by P-gp, which is highly expressed at the BBB, limiting the brain uptake of many lipophilic drugs. P-gp exhibits multiple substrate binding sites, enabling simultaneous interactions with various compounds61,62,63. Molecular docking was performed utilizing the the five drug molecules against the modeled P-gp protein (See the detailed modeling process in the “MD Simulation of P-gp with Drugs” subsection). MD simulations were then conducted to further analyze the molecular mechanism of the xenobiotics binding and the substrate-induced conformational changes in P-gp (Fig. S5). These simulations provide insights into the dynamic interactions between drugs and P-gp, crucial for understanding drug efflux and ultimately for designing drugs with improved BBB penetration64.

Binding patterns and key interactions between drug molecules and P-gp. Drug molecules are shown as colored sticks, key residues as white sticks. Hydrogen bond interactions are shown with yellow dashed lines and occupancy probabilities (numbers in percentage), CH-π or π-π interactions with green dashed lines.

The transmembrane domain of P-gp, primarily composed of non-polar residues (Phe, Leu, Val), facilitates interactions with substrates mainly through hydrophobic and van der Waals interactions. Its binding pocket’s deep location within the helical region also emphasizes the role of non-polar interactions. Meanwhile, a few polar residues like Tyr and Gln could also provide hydrogen bond donors. This aligns with findings by Li-Blatter et al., emphasizing the role of hydrogen bonding and weak electrostatic interactions (cation-π, CH-π, π-π) in P-gp’s substrate binding65. Binding mode analysis according to the MD simulation (Fig. 7) reveals distinct binding modes for five drugs: vebreltinib, savolitinib and glumetinib predominantly interact via π-π or CH-π interactions with F336, F343 and F983. Vebreltinib and savolitinib exhibit strong π-π interactions with F343 via their 6 − 5 fused heterocyclic rings, while glumetinib forms a similarly strong π-π interaction with F343 through its pyrazole ring. On the opposite side, glumetinib’s pyrazole ring establishes additional π-π interactions with F336, whereas vebreltinib and savolitinib engage in CH-π interactions with F336 through their cyclopropyl and methyl group on pyrazole ring, respectively. Furthermore, glumetinib has a strong π-π interaction with F983 via its 6 − 5 fused heterocyclic ring, savolitinib exhibits a strong π-π interaction with F983 through the pyrazole ring, but vebreltinib shows a weaker interaction with F983. The detailed interaction strengths are provided in the residues energy decomposition below. Glumetinib shows a higher propensity (85%) for hydrogen bonding with Y953 compared to vebreltinib and savolitinib (56–58%), potentially due to structural similarities leading to similar binding patterns. On the other hand, capmatinib forms strong hydrogen bonds with S344, E875 and Y310, alongside π-π interactions with F336 and F983 with its quinoline ring and 6 − 5 fused heterocyclic ring, respectively. Tepotinib exhibits strong π-π interactions with both F336 and F983 via its benzene ring, and also forms a unique interaction with F728 through its pyrimidine ring. Tepotinib also exhibits a unique strong hydrogen bond between its charged piperazine and Q725, another hydrogen bond with Y953. Consequently, this increases the likelihood of capmatinib and tepotinib being expelled from the brain as substrates for P-gp.

MM/GBSA calculations, based on the complex conformations from the last stable 50 ns of the MD trajectories, revealed distinct binding free energy profiles among the studied drugs (Fig. 8). Tepotinib displayed the highest binding affinity (− 71.3 kcal/mol) towards P-gp, primarily due to its positively charged functional group forming strong hydrogen bonding with Q725, as evidenced by the significant energy contribution of Q725 (− 6.34 kcal/mol). This suggests tepotinib’s potential as a P-gp substrate. While capmatinib also exhibited a high binding free energy (− 49.62 kcal/mol), vebreltinib, savolitinib, and glumetinib showed lower and comparable binding affinities (− 39.02, − 38.12 and − 39.73 kcal/mol, respectively). Residue-specific free energy decomposition analysis of π-π interactions (Fig. 8B) highlighted the contributions of F336, F343 and F983 to the binding of all five drugs. Notably, F728 contributed significantly only to tepotinib’s binding, further supporting its strong affinity.

Integrating the dynamical and thermodynamic data, tepotinib exhibits a unique strong hydrogen bond between its charged piperazine and Q725, another hydrogen bond with Y953, and π-π interactions with F336, F983 and F728. So tepoinib emerges as a likely P-gp substrate due to its stable binding mode and high binding free energy. Capmatinib, while exhibiting a stable binding mode, may be a weaker substrate due to its lower free energy compared to tepotinib. Conversely, vebreltinib, savolitinib and glumetinib are unlikely to be P-gp substrates due to their lower binding free energies, fewer hydrogen bonds, and predominant reliance on hydrophobic and π-π interactions. Given the complex conformational changes and functional regulation possibly involved in P-gp-mediated transport47,66, further investigation using advanced simulation techniques, such as enhanced sampling, is expected in the future study to elucidate the intricate mechanisms underlying substrate transport.

In summary, our molecular dynamics simulations of various drugs and P-gp have revealed that while the interior of P-gp is predominantly hydrophobic, the formation of hydrogen bonds between ligand polar atoms and P-gp significantly enhances their interaction. Consequently, this increases the likelihood of these ligands being expelled from the brain as substrates for P-gp. Therefore, when designing drugs, it is crucial to consider maintaining an appropriate level of lipophilicity in order to avoid excessive polarity that may hinder their ability to cross the blood-brain barrier and achieve desired therapeutic efficacy.

MDCK-MDR1 cell assay

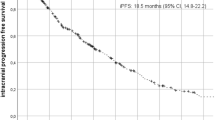

CNS metastasis is a common occurrence in patients with advanced NSCLC and poses challenges for treatment and prognosis. Among patients with METex14 alterations, 73% had metastatic disease67, with 17% (95% CI 10–27%; 14 out of 83 patients) having brain metastasis, including one patient with leptomeningeal disease. Additionally, 19% of patients (95% CI 11–29%; 16 out of 83 patients) developed brain metastasis later in their disease course. In total, CNS metastases were identified in 36% of patients (95% CI 10–27%; 30 out of 83 patients) with METex14-altered lung cancers. In clinical studies, vebreltinib, glumetinib, and capmatinib have shown good blood-brain permeability effects, with objective response rates (ORR) reaching 100%7, 85%5 and 54%68, respectively. Conversely, savolitinib and tepotinib had poor effects, with ORRs of less than 50%69,70. Consequently, for the next experimental analysis, we have opted for inhibitors with good blood-brain permeability effects.

The MDCK-MDR1 cell model serves as an efficient in vitro blood-brain barrier (BBB) screening tool for evaluating the CNS permeability of different drugs, guiding drug discovery efforts71. This model involves MDCK cells transfected with the human MDR1 gene, resulting in overexpression of polar-distributed P-gp. Unlike endogenous transporters in native MDCK cells, which can be disregarded, this transfected cell line is ideal for studying P-gp mediated transport phenomena. The MDCK-MDR1 cell model, a well-established in vitro tool for assessing blood-brain barrier (BBB) penetration, was employed to evaluate the CNS permeability of three clinically relevant type Ib MET inhibitors: vebreltinib, glumetinib, and capmatinib, which are known for their significant BBB-penetrating properties (Table 1).

The BBB consists of the pia mater between the blood circulation and brain parenchyma, the brain capillary endothelium with choroid plexus, and the surrounding glial membrane. This barrier rigorously limits drug penetration, with most drugs primarily entering brain cells via passive diffusion. Therefore, a higher apparent permeability coefficient indicates enhanced ability for drugs to traverse the BBB. BBB endothelial cells prominently express P-gp transporters at their apical surfaces. High efflux activity of these transporters diminishes BBB permeability. Most CNS drugs exhibit high passive permeability (Papp > 15 × 10− 6 cm/s), and an efflux ratio (ER) less than 2.5 suggests minimal susceptibility to P-gp efflux. The bidirectional permeability experiments revealed that vebreltinib exhibited a notably high apparent permeability coefficient (Papp(A−B) = 21.16 cm/s × 10− 6) and a low efflux ratio as 1.23, showing it may possess relatively robust brain distribution. Similarly, capmatinib exhibited a high permeability coefficient (Papp(A−B) = 24.06 cm/s × 10− 6) and a lower efflux rate as 1.11. Analysis by umbrella sampling simulations reveals that vebreltinib and capmatinib have favorable profiles for crossing the BBB, characterized by lower energy barriers of about 12.9 and 16.6 kcal/mol, respectively. The bidirectional permeability experiments revealed that vebreltinib and capmatinib exhibited a notably high apparent permeability coefficient which align well with the experimental data.

On the one hand, capmatinib was reported as a P-gp substrate72, agreeing with our findings that capmatinib showed the largest efflux permeability (Papp(B−A) = 26.72 cm/s × 10− 6) among the three drugs. On the other hand, the good blood-brain permeability effects of capmatinib may be due to its low passive diffusion free energy barrier (Fig. 5A). Glumetinib exhibited low efflux but a also low Papp(A−B) value, agreeing with the computational results that glumetinib had high passive diffusion free energy barrier while not intending to bind P-gp, showing its limited membrane penetration effectiveness, both influx and efflux.

Our findings underscore the importance of structural considerations in designing MET inhibitors that not only bind effectively to MET but also possess favorable pharmacokinetic properties for CNS penetration. These insights are critical for optimizing treatment strategies for NSCLC patients. While our focus is on MET abnormalities, NSCLC is a heterogeneous disease with various driver mutations (e.g., EGFR, ALK, ROS1) that can influence treatment responses. By understanding how different drugs interact with the MET pathway and their pharmacokinetic profiles, clinicians can tailor therapies based on a patient’s specific genetic makeup. For instance, patients with concurrent mutations might benefit from combination therapies that target multiple pathways simultaneously. Overall, these findings underscore the potential for a more individualized approach in managing NSCLC, ultimately aiming for improved outcomes.

Our transmembrane simulation model showed that vebreltinib and capmatinib exhibited low energy barriers for transmembrane crossing, suggesting they can penetrate cell membranes easily, consistent with their high experimental permeability. Our P-gp substrate binding model showed that capmatinib is likely to be a substrate of P-gp, and the experimental results showed that capmatinib has the largest efflux permeability and is the substrate of P-gp. So our models play a crucial role in the current development and testing of MET inhibitors. They facilitate an understanding of drug interactions at a molecular level, contributing to the design of more effective inhibitors with optimized pharmacokinetic properties. Models for clinical development typically focus on cellular responses and pharmacodynamics, while our models provide insights into drug permeation and membrane interactions. It’s advantages include higher throughput for screening drug permeability and a more realistic representation of the membrane environment, enabling better predictions of in vivo behavior.

Conclusions

Vebreltinib and glumetinib have demonstrated high objective response rates (ORR) in treating NSCLC with MET exon 14 mutations, particularly in patients with brain metastases. Vebreltinib also shows efficacy in treating mutant astrocytoma or glioblastoma, indicating broader potential beyond NSCLC. In this article, we focus on the efficacy and mechanisms of type Ib MET inhibitors, vebreltinib, glumetinib, capmatinib, tepotinib and savolitinib, in treating non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with MET exon 14 skipping mutations.

Type Ib MET inhibitors demonstrate potent binding to MET through a U-shaped binding mode and strong interactions with crucial residues such as Y1230. This specific binding pattern enhances their selectivity and efficacy against MET-exon 14 skipping mutations. Vebreltinib, in particular, is easier to adopts a U-shaped conformation that enables effective inhibition of kinase activity by facilitating entry into the ATP pocket. Our study primarily focused on the binding affinity and initial activity of the molecules, while favorable binding alone does not necessarily demonstrate efficacy. It’s important to demonstrate both proximal and distal pharmacodynamic (PD) effects to establish a stronger link to efficacy in future studies.

In order to evaluate the BBB permeability of drugs, we constructed a BBB membrane model to closely replicate the unique characteristics of the human BBB, which restricts drug permeability due to its highly selective nature. Key features of this model include a high density of tight junctions, specific transporter proteins, and low passive permeability, which collectively mimic the restrictive environment of the BBB. Additionally, this model incorporates relevant efflux transporters P-gp, which is essential for evaluating the active transport processes that influence drug absorption and retention in the brain. Analysis by umbrella sampling simulations reveals that vebreltinib and capmatinib have favorable profiles for crossing the BBB, characterized by lower energy barriers. This property is crucial for CNS drug delivery, as drugs with lower energy barriers are more likely to penetrate brain tissue effectively. P-gp is a main factor contributing to multi drug resistance and the consequent failure of chemotherapy. While vebreltinib, savolitinib and glumetinib show minimal interaction with P-gp, suggesting low susceptibility to efflux, capmatinib and tepotinib exhibit higher interaction with P-gp, indicating potential limitations in CNS penetration due to P-gp mediated efflux. Experimental permeability studies in the MDCK-MDR1 cell line corroborate simulation findings, showing that vebreltinib and capmatinib have higher permeability coefficients. Taken together, the results suggest vebreltinib possesses superior BBB permeability. These findings underscore the importance of structural considerations in designing MET inhibitors that not only bind effectively to MET but also possess favorable pharmacokinetic properties for CNS penetration. These insights are critical for optimizing treatment strategies for NSCLC patients with MET abnormalities and brain metastases.

In conclusion, the success of vebreltinib in treating CNS tumors highlights its potential as effective therapies for patients with MET abnormalities, emphasizing the need for continued development of drugs with improved CNS permeation and selectivity profiles. These insights and dynamic simulation methods pave the way for future advancements in targeted therapies for CNS tumors.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files; further inquiries can be directed to the author, Zheng Zheng: johnzhengzz@whut.edu.cn.

References

Frampton, G. M. et al. Activation of MET via diverse exon 14 splicing alterations occurs in multiple tumor types and confers clinical sensitivity to MET inhibitors. Cancer Discov. 5, 850–859 (2015).

Yeung, S. F. et al. Profiling of oncogenic driver events in Lung Adenocarcinoma revealed MET mutation as independent prognostic factor. J. Thorac. Oncol. 10, 1292–1300 (2015).

Rosset, M., Reifegerste, D., Baumann, E., Kludt, E. & Weg-Remers, S. [Trends in cancer information services over 25 years: an analysis of inquiries from patients and relatives made to the Cancer Information Service of the German Cancer Research Center from 1992 to 2016]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 62, 1120–1128 (2019).

Ai, J. et al. Preclinical evaluation of SCC244 (glumetinib), a Novel, Potent, and highly selective inhibitor of c-Met in MET-dependent Cancer models. Mol. Cancer Ther. 17, 751–762 (2018).

Yu, Y. et al. Gumarontinib in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer harbouring MET exon 14 skipping mutations: a multicentre, single-arm, open-label, phase 1b/2 trial. EClinicalMedicine 59, 101952 (2023).

Shih, J. et al. Abstract : Bozitinib, a highly selective inhibitor of cMet, demonstrates robust activity in gastric, lung, hepatic and pancreatic in vivo models. Cancer Res. 77, 2096–2096 (2017)

Yang, J. J. et al. 1379P preliminary results of phase II KUNPENG study of vebreltinib in patients (pts) with advanced NSCLC harboring c-MET alterations. Ann. Oncol., (2023).

Bao, Z. et al. PTPRZ1-METFUsion GENe (ZM-FUGEN) trial: study protocol for a multicentric, randomized, open-label phase II/III trial. Chin. Neurosurg. J. 9, 21 (2023).

Liu, Z. et al. Molecular insights on the conformational transitions and activity regulation of the c-Met kinase Induced by Ligand Binding. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 63, 4147–4157 (2023).

Curran, M. P. Crizotinib: in locally advanced or metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. Drugs 72, 99–107 (2012).

Dhillon, S. & Capmatinib First Approval Drugs 80, 1125–1131, (2020).

Markham, A. & Tepotinib First Approval Drugs 80, 829–833, (2020).

Markham, A. & Savolitinib First Approval Drugs 81, 1665–1670, (2021).

Yakes, F. M. et al. Cabozantinib (XL184), a novel MET and VEGFR2 inhibitor, simultaneously suppresses metastasis, angiogenesis, and tumor growth. Mol. Cancer Ther. 10, 2298–2308 (2011).

Yan, S. B. et al. LY2801653 is an orally bioavailable multi-kinase inhibitor with potent activity against MET, MST1R, and other oncoproteins, and displays anti-tumor activities in mouse xenograft models. Invest. New. Drugs. 31, 833–844 (2013).

Engstrom, L. D. et al. Glesatinib exhibits Antitumor Activity in Lung Cancer models and patients harboring MET exon 14 mutations and overcomes mutation-mediated resistance to type I MET inhibitors in nonclinical models. Clin. Cancer Res. 23, 6661–6672 (2017).

Calles, A. et al. Tivantinib (ARQ 197) efficacy is independent of MET inhibition in non-small-cell lung cancer cell lines. Mol. Oncol. 9, 260–269 (2015).

Hu, H. et al. Mutational Landscape of secondary Glioblastoma guides MET-Targeted trial in Brain Tumor. Cell 175(e1618), 1665–1678 (2018).

Bhardwaj, V., Singh, R., Singh, P., Purohit, R. & Kumar, S. Elimination of bitter-off taste of stevioside through structure modification and computational interventions. J. Theor. Biol. 486, 110094 (2020).

Tanwar, G. & Purohit, R. Gain of native conformation of Aurora A S155R mutant by small molecules. J. Cell. Biochem. 120, 11104–11114 (2019).

Kumar, A. & Purohit, R. Computational investigation of pathogenic nsSNPs in CEP63 protein. Gene 503, 75–82 (2012).

Singh, R., Bhardwaj, V. K., Das, P. & Purohit, R. Identification of 11β-HSD1 inhibitors through enhanced sampling methods. Chem. Commun. (Camb). 58, 5005–5008 (2022).

Purohit, R. et al. Studies on flexibility and binding affinity of Asp25 of HIV-1 protease mutants. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 42, 386–391 (2008).

K, B. & Purohit, R. Mutational analysis of TYR gene and its structural consequences in OCA1A. Gene 513, 184–195 (2013).

Dorsch, D. et al. Identification and optimization of pyridazinones as potent and selective c-Met kinase inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 25, 1597–1602 (2015).

Collie, G. W. et al. Structural and molecular insight into resistance mechanisms of first generation cMET inhibitors. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 10, 1322–1327 (2019).

Molecular Operating Environment (MOE), 2020.09 Chemical Computing Group ULC: Montreal, QC, Canada. (2022). https://www.chemcomp.com/Products.htm.

Wang, J., Wolf, R. M., Caldwell, J. W., Kollman, P. A. & Case, D. A. Development and testing of a general amber force field. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1157–1174 (2004).

Maier, J. A. et al. ff14SB: improving the Accuracy of protein side chain and backbone parameters from ff99SB. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 11, 3696–3713 (2015).

Jakalian, A., Bush, B. L., Jack, D. B. & Bayly, C. I. Fast, efficient generation of high-quality atomic charges. AM1-BCC model: I. Method. J. Comput. Chem. 21, 132–146 (2000).

Jakalian, A., Jack, D. B. & Bayly, C. I. Fast, efficient generation of high-quality atomic charges. AM1-BCC model: II. Parameterization and validation. J. Comput. Chem. 23, 1623–1641 (2002).

Ryckaert, J. P., Ciccotti, G. & Berendsen, H. J. C. Numerical integration of the cartesian equations of motion of a system with constraints: molecular dynamics of n-alkanes. J. Comput. Phys. 23, 327–341 (1977).

Essmann, U. et al. A smooth particle mesh Ewald method. J. Chem. Phys. 103, 8577–8593 (1995).

Jo, S., Kim, T., Iyer, V. G. & Im, W. CHARMM-GUI: a web-based graphical user interface for CHARMM. J. Comput. Chem. 29, 1859–1865 (2008).

Lee, J. et al. CHARMM-GUI Input Generator for NAMD, GROMACS, AMBER, OpenMM, and CHARMM/OpenMM simulations using the CHARMM36 Additive Force Field. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 12, 405–413 (2016).

Lee, J. et al. CHARMM-GUI Membrane Builder for Complex Biological Membrane Simulations with glycolipids and lipoglycans. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 15, 775–786 (2019).

Campbell, S. D., Regina, K. J. & Kharasch, E. D. Significance of lipid composition in a blood-brain barrier–mimetic PAMPA assay. J. BioMol. Screen. 19, 437–444 (2014).

Klauda, J. B. et al. Update of the CHARMM all-Atom Additive Force Field for lipids: validation on six lipid types. J. Phys. Chem. B. 114, 7830–7843 (2010).

Venable, R. M. et al. CHARMM all-Atom Additive Force Field for Sphingomyelin: elucidation of Hydrogen Bonding and of positive curvature. Biophys. J. 107, 134–145 (2014).

Yu, W., He, X., Vanommeslaeghe, K. & MacKerell, A. D. Jr. Extension of the CHARMM general force field to sulfonyl-containing compounds and its utility in biomolecular simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 33, 2451–2468 (2012).

Vanommeslaeghe, K. et al. CHARMM general force field: a force field for drug-like molecules compatible with the CHARMM all-atom additive biological force fields. J. Comput. Chem. 31, 671–690 (2010).

Berendsen, H. J. C., Postma, J. P. M., van Gunsteren, W. F., DiNola, A. & Haak, J. R. Molecular dynamics with coupling to an external bath. J. Chem. Phys. 81, 3684–3690 (1984).

Abraham, M. J. et al. High performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX 1–2. GROMACS, 19–25 (2015).

Van Der Spoel, D. et al. Fast, flexible, and free. J. Comput. Chem. 26. GROMACS, 1701–1718 (2005).

Kumar, S., Rosenberg, J. M., Bouzida, D., Swendsen, R. H. & Kollman, P. A. THE weighted histogram analysis method for free-energy calculations on biomolecules. I. The method. J. Comput. Chem. 13, 1011–1021 (1992).

Hub, J. S., de Groot, B. L. & van der Spoel, D. g_wham—A free weighted histogram analysis implementation including robust error and Autocorrelation estimates. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 6, 3713–3720 (2010).

Alam, A., Kowal, J., Broude, E., Roninson, I. & Locher, K. P. Structural insight into substrate and inhibitor discrimination by human P-glycoprotein. Science 363, 753–756 (2019).

Waterhouse, A. et al. SWISS-MODEL: homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, W296–w303 (2018).

Feng, B. et al. Validation of human MDR1-MDCK and BCRP-MDCK cell lines to improve the prediction of Brain Penetration. J. Pharm. Sci. 108, 2476–2483 (2019).

Liu, X. et al. A novel kinase inhibitor, INCB28060, blocks c-MET-dependent signaling, neoplastic activities, and cross-talk with EGFR and HER-3. Clin. Cancer Res. 17, 7127–7138 (2011).

Bladt, F. et al. EMD 1214063 and EMD 1204831 constitute a new class of potent and highly selective c-Met inhibitors. Clin. Cancer Res. 19, 2941–2951 (2013).

Jia, H. et al. Discovery of (S)-1-(1-(Imidazo[1,2-a]pyridin-6-yl)ethyl)-6-(1-methyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)-1H-[1,2,3]triazolo[4,5-b]pyrazine (volitinib) as a highly potent and selective mesenchymal-epithelial transition factor (c-Met) inhibitor in clinical development for treatment of cancer. J. Med. Chem. 57, 7577–7589 (2014).

Genheden, S. & Ryde, U. The MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA methods to estimate ligand-binding affinities. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 10, 449–461 (2015).

Pardridge, W. M. The blood-brain barrier: Bottleneck in brain drug development. NeuroRX 2, 3–14 (2005).

Di, L., Kerns, E. H., Fan, K., McConnell, O. J. & Carter, G. T. High throughput artificial membrane permeability assay for blood-brain barrier. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 38, 223–232 (2003).

Mensch, J. et al. Evaluation of various PAMPA models to identify the most discriminating method for the prediction of BBB permeability. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 74, 495–502 (2010).

Xiong, B. et al. Strategies for structural modification of small molecules to improve blood-brain barrier penetration: a recent perspective. J. Med. Chem. 64, 13152–13173 (2021).

Liu, L. et al. Prediction of the blood–brain barrier (BBB) permeability of Chemicals based on machine-learning and ensemble methods. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 34, 1456–1467 (2021).

Siwy, C. M., Delfing, B. M., Lockhart, C., Smith, A. K. & Klimov, D. K. Partitioning of Abeta peptide fragments into blood-brain barrier Mimetic Bilayer. J. Phys. Chem. B. 125, 2658–2676 (2021).

Liang, Y., Zhi, S., Qiao, Z. & Meng, F. Predicting blood–brain barrier permeation of Erlotinib and JCN037 by Molecular Simulation. J. Membr. Biol. 256, 147–157 (2023).

Dey, S., Ramachandra, M., Pastan, I. H., Gottesman, M. M. & Ambudkar, S. V. evidence for two nonidentical drug-interaction sites in the human P-glycoprotein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94 20, 10594–10599 (1997).

Martin, C. et al. Communication between multiple drug binding sites on P-glycoprotein. Mol. Pharmacol. 58, 624–632 (2000).

Loo, T. W., Bartlett, M. C. & Clarke, D. M. Simultaneous binding of two different drugs in the binding pocket of the human multidrug resistance P-glycoprotein. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 39706–39710 (2003).

Liu, W., Liu, Z., Liu, H., Westerhoff, L. M. & Zheng, Z. Free Energy calculations using the movable type method with Molecular Dynamics Driven protein–ligand sampling. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 62, 5645–5665 (2022).

Li-Blatter, X. & Seelig, A. Exploring the P-glycoprotein binding cavity with polyoxyethylene alkyl ethers. Biophys. J. 99, 3589–3598 (2010).

Verhalen, B. et al. Energy transduction and alternating access of the mammalian ABC transporter P-glycoprotein. Nature 543, 738–741 (2017).

Offin, M. et al. CNS Metastases in patients with MET exon 14–Altered lung cancers and outcomes with Crizotinib. JCO Precision Oncol., 871–876, (2020).

Garon, E. B. et al. Abstract CT082: Capmatinib in METex14-mutated (mut) advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): results from the phase II GEOMETRY mono-1 study, including efficacy in patients (pts) with brain metastases (BM). Cancer Res. 80, CT082–CT082 (2020).

Sakai, H. et al. Tepotinib in patients with NSCLC harbouring MET exon 14 skipping: Japanese subset analysis from the phase II VISION study. Jpn J. Clin. Oncol. 51, 1261–1268 (2021).

Lu, S. et al. Once-daily savolitinib in Chinese patients with pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinomas and other non-small-cell lung cancers harbouring MET exon 14 skipping alterations: a multicentre, single-arm, open-label, phase 2 study. Lancet Respir Med. 9, 1154–1164 (2021).

Jiang, L. et al. Application of a high-resolution in vitro human MDR1-MDCK assay and in vivo studies in preclinical species to improve prediction of CNS drug penetration. Pharmacol. Res. Perspect. 10, e00932 (2022).

NDA/BLA. Multi-disciplinary Review and Evaluation {NDA 213591}. July 24, (2019).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the support of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 22203064).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Zhenhao Liu, Wenlang Liu, Xinyi Shen, Hao Liu and Zheng Zheng conceived the idea and designed the experiment. Zhenhao Liu, Xinyi Shen and Tao Jiang performed the molecular dynamics simulations. Wenlang Liu and Xionghao Li performed the cell experiments. Zhenhao Liu, Hao Liu and Zheng Zheng analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Z., Liu, W., Shen, X. et al. Molecular mechanism of type ib MET inhibitors and their potential for CNS tumors. Sci Rep 15, 6926 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85631-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85631-w