Abstract

Invasive infections with Aspergillus fumigatus in ICU patients are linked to high morbidity and mortality. Diagnosing invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (IPA) in non-immunosuppressed patients is difficult, as Aspergillus antigen (galactomannan [GM]) may have other causes. This retrospective study analyzed 160 ICU surgical patients with positive GM in broncho-alveolar lavage fluid (BALF), classifying them based on AspICU criteria for suspected IPA (pIPA) or aspiration. Patients with pIPA had higher disease severity than those with aspiration, including higher dialysis rates, organ transplantation, corticosteroid use, and Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score. Aspergillus culture was positive in 47.0% of pIPA cases but only 2.6% of aspiration cases (p < 0.001). SOFA score at first positive GM in BALF independently predicted 28-day mortality. In surgical patients with a positive GM in BALF, aspiration is more likely if there’s no corticosteroid therapy, negative Aspergillus culture, and a history of aspiration events. Diagnosis of pIPA requires Aspergillus culture or prior corticosteroid therapy in this cohort of critically ill patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Invasive fungal diseases (IFD) have become a major threat in critically ill patients as the population at risk continues to rise1,2,3. Classical (host) risk factors for IFD, including neutropenia due to chemotherapy and allogeneic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), have been known for years4. New groups of patients without traditional risk factors are constantly being discovered. Examples include patients after solid organ transplantation (SOT); patients with liver or kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), malnutrition or diabetes mellitus; critically ill patients with sepsis; and patients taking corticosteroids (particularly with doses of > 20 mg of prednisone or equivalent daily)5. Past outbreaks with influenza and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) have also been associated with increased invasive Aspergillus infections with the lung as the mainly affected organ, termed virus associated pulmonary aspergillosis (VAPA). The outcome of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (IPA) in ICU patients is grim: mortality rates are often > 50%5,6,7.

The true incidence of IPA is difficult to establish because a definite diagnosis requires a lung biopsy with histopathological examination showing invasive growth. In critically ill patients with respiratory failure, an impaired coagulation status and hemodynamic instability, performing a lung biopsy might be too risky. Therefore, non-biopsy-guided diagnostic algorithms have been established, integrating clinical, radiological and microbiological features. One of these algorithms by EORTC/MSG was revised in 20084, but it was only applicable for patients under immunosuppression and/or with classical host factors. In 2012, Blot et al.8 reported the AspICU algorithm based on an external validation study incorporating ICU patients without traditional “host factors”. The AspICU study showed that the classical features on computed tomography (CT) scans, including the halo sign or the air-crescent sign, are rarely noted in patients without neutropenia. In these patients, an entry criterion to diagnose IPA in the AspICU algorithm is a positive lower respiratory tract specimen culture. Because researchers have described ≤ 65% sensitivity for lower respiratory tract specimen cultures after broncho-alveolar lavage (BAL)9, non-culture-based methods are urgently needed.

Galactomannan (GM) is a polysaccharide and a major component of the cell wall of Aspergillus spp10. Angioinvasion by Aspergillus spp. leads to the release of GM in the circulation11 and can be detected in different fluids (broncho-alveolar lavage fluid [BALF], serum and cerebrospinal fluid). BALF samples are superior to blood samples, especially in patients without neutropenia. In this population, a galactomannan index (GMI) in BALF reported as an optical density index (ODI) ≥ 1.0 is probably associated with an invasive disease. False-positive GM results have been described in a variety of situations such as Histoplasma infections10, therapy with intravenous human immunoglobulin12 or caspofungin administration13. A few case reports have indicated false-positive GM testing in patients after aspiration of enteral nutrition14 and in patients with aspiration pneumonia15. In another case, a patient with mucositis after HSCT had false-positive GM serum results caused by oral nutritional supplements16. Here, we examined the impact of false-positive GM results in BALF in a heterogeneous group of surgical patients who were specifically evaluated for the impact of aspiration.

Results

Baseline characteristics and demographics

We included a total of 160 patients in the study. Ninety-one patients (56.9%) were classified as non-IPA (colonisation only); we did not include these patients in the final analysis. In the remaining patients, 30 (18.8%) had pIPA and 39 (24.4%) had aspiration. The baseline characteristics of all included patients are displayed in detail in Table 1. Patients with aspiration were older compared with patients with pIPA (72 vs. 61 years, p < 0.01). Patients with pIPA showed a higher degree of illness: liver cirrhosis and SOT was more common in this group (50.0% vs. 5.1%, p < 0.001, and 63.0% vs. 0%, p < 0.001, respectively). Corticosteroid therapy was also significantly more common in patients with pIPA compared with patients with aspiration (97.0% vs. 21.0%, p < 0.001). The need for kidney replacement therapy was higher in patients with pIPA (40.0% vs. 7.7%, p = 0.001). The two groups also differed in terms of the ASA status (p = 0.04) and the SOFA scores at ICU admission (11 vs. 7 points, p < 0.01). The time spent in the ICU and the duration of mechanical ventilation was longer in patients with pIPA compared with patients with aspiration (47 vs. 28 days, p = 0.02 and 453 vs. 249 h, p = 0.07, respectively), indicating that patients with pIPA were more severely ill. In addition, the SOFA score in patients with pIPA was higher at the first detection of GM in BALF (13 vs. 11 points, p = 0.02). The first and highest GM values in BALF were significantly higher in patients with pIPA compared with patients with aspiration (5.8 vs. 2.7, p < 0.001 and 4.5 vs. 2.0, p < 0.01, respectively). Aspergillus fumigatus cultures from BALF were positive for 47.0% of patients with pIPA but only for 2.6% of patients with aspiration (p < 0.001). The patient groups differed significantly in terms of antifungal therapy; patients with pIPA received antifungal prophylaxis more often (23.0% vs. 5.1%, p = 0.04), a first-line antifungal therapy (90.0% vs. 38.0%, p < 0.001) and a switch to a second-line antifungal treatment (50.0% vs. 7.7%, p < 0.001) compared with patients with aspiration. Table 2 shows the microbiological test results and the corresponding antifungal treatments in all included patients.

Outcome

The primary outcome, mortality within 28 days after ICU admission, did not differ between patients with pIPA and aspiration (31% vs. 32%, p = 0.9).

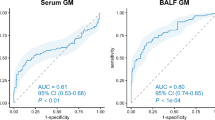

Uni- and multivariate analyses

Only an elevated SOFA score (an increase of 1 point) during first GM positivity was associated with an increased 28-day mortality risk (HR 1.20, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.04–1.39) in the multivariate analysis. By contrast, neither the highest GM value nor the SOFA score upon ICU admission were risk factors for 28-day mortality (p = 0.14 and p = 0.50, respectively). Table 3 lists the risk factors for death within 28 days after ICU admission.

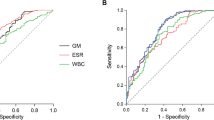

Probability of aspiration

We developed a logistic model including the use of corticosteroids and positivity of Aspergillus culture to predict the patient group membership. The model’s explanatory power was substantial with a co-efficient of discrimination (Tjur’s R2) of 0.65, and both effects were statistically significant: no usage of corticosteroids and a negative Aspergillus culture predict a high probability of belonging to the aspiration group (Fig. 1). We also calculated sensitivity and specificity for the probability of belonging to the pIPA group in our patient cohort. Interestingly, a combination of a first GM value in BALF and a positive A. fumigatus specimen culture from BALF had a sensitivity of 0.5 and a specificity of 0.86. The combination of the highest GM value in BALF and a positive A. fumigatus specimen culture from BALF showed a higher sensitivity (0.7) but a lower specificity (0.8). These findings again point towards the fact that a negative Aspergillus specimen culture can rule out pIPA in patients with a low-risk profile or signs of aspiration.

Enteral nutritional supplementation

We tested several enteral nutritional supplements with the Platelia™ Aspergillus ELISA in our department. Most striking was the fact that the higher the amount of soy in the supplements, the higher the measured GM values. In fact, every supplement tested positive for GM, but the lower the fraction of protein (and the less soy-based protein), the lower the GM values. Table S2 includes the values for the enteral nutritional supplements we tested. No difference was seen in terms of application of parenteral- or enteral nutrition between pIPA and ASP-patients in the last three days before GM detection in BALF (93% vs. 77%, p = 0.2 and 70% vs. 59%, p = 0.6 respectively). Additional information about the distribution of each supplement in each group is provided in Table S3.

Discussion

Here, we have described the prevalence and outcome of patients with positive GM detection in BALF due to aspiration or pIPA in a mixed cohort of surgical ICU patients. IPA is most often diagnosed in patients with “classical” risk factors (e.g. neutropenia, haematological malignancy and recipients of an allogeneic HSCT)4,10,17. The group of at-risk patients with non-traditional risk factors (e.g. SOT recipients, sepsis, severe viral infections, diabetes mellitus, COPD, malnutrition and liver cirrhosis) has increased steadily over the last 10–20 years18,19,20,21. The AspICU study8, an international, multicentre study examining the incidence of IPA in 30 ICUs in 8 countries, showed that > 90% of included patients had co-morbidities: respiratory diseases (including COPD), cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus and immunosuppressive therapy. We found similar results in our cohort. Most patients with pIPA presented with additional risk factors: >50% of patients were SOT recipients, 50% had heart insufficiency and 33% received corticosteroids because of sepsis. Even though some patients with pIPA lack traditional risk factors, they are usually more severely ill. For example, the SOFA scores in the AspICU cohort8 were higher in proven IPA (median 11, interquartile range [IQR] 7–14) or pIPA (median 9, IQR 6–12) compared with patients with Aspergillus colonisation only (median 5, IQR 2–9). In our study, patients with pIPA also showed significantly higher SOFA scores upon ICU admission (11 vs. 7 points) and during the first GM positivity (13 vs. 11 points) compared with patients with aspiration. This is in line with our last published study22, in which we also showed that patients with pIPA presented with higher SOFA scores upon ICU admission compared with patients with Aspergillus colonisation only (11 vs. 8 points, p = 0.04). In a retrospective study with patients with severe COVID-19 and concomitant COVID-19-associated pulmonary aspergillosis (CAPA), elevated disease severity (as assessed by the SOFA score) and the need for organ support were also significantly linked to a worse outcome23.

In a multicentre study based in Italy, previous use of corticosteroids, mainly due to autoimmune disease or COPD, was a major risk factor in developing IPA24. IPA risk is also augmented in patients receiving corticosteroids only during their hospital stay. This cohort of patients is increasing, especially those admitted to the ICU with septic shock and requiring high doses of vasopressors11. In our cohort, 97% of patients with pIPA received corticosteroid therapy, mostly due to SOT or sepsis. Corticosteroid therapy increases the susceptibility to opportunistic infections, including invasive aspergillosis25. This is primarily through its immunomodulatory effects on immune cells. For example, glucocorticoids reduce the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and LC3-associated phagocytosis (LAP), leading to an altered fungicidal ability of myeloid cells26. In a human ex vivo cell model with neutrophil granulocytes from healthy volunteers and A. fumigatus, the Aspergillus defence provided by neutrophil granulocytes was significantly stronger in the afternoon than in the morning, due to potentially (significantly) different cortisol levels measured in the included volunteers27. A systematic review and meta-analysis of patients with severe influenza clearly showed a significant relation between corticosteroid use and IPA6. Data regarding other underlying diseases, such as COVID-19, are more conflicting. A recently published meta-analysis with more than 6000 patients with COVID-19 indicated that treatment with corticosteroids is a significant risk factor for developing CAPA28, although the actual guidelines recommend 6 mg of dexamethasone per day, a potent glucocorticoid, for up to 10 days, in patients with severe COVID-1929. Corticosteroids should be prescribed with caution in critically ill patients, and physicians must weigh the risks against the benefits, especially in patients with a high risk for IPA.

Although the Platelia™ assay was initially only approved to measure GM in serum, BALF was added as a validated sample type in 201110. There is still a debate about the cutoff that should be used. With a GM cutoff of ≥ 1.0 in BALF, as proposed in the updated consensus definitions by EORTC/MSGERC in 202110, sensitivity ranges from 0.75 to 0.86 and specificity ranges from 0.94 to 0.95. Compared with GM in serum, the sensitivity of GM in BALF is similar in patients with or without haematological diseases and in patients with and without neutropenia.

The outcomes in our study did not differ between patients with pIPA and aspiration. This is most likely due to the timely and accurate diagnostic workup of patients with pIPA rather than IPA itself. Another reason might lie in the severe illness of all included patients. The SOFA scores during first GM positivity were > 10 points in all patients. Only an elevated SOFA score (an increase of 1 point) during first GM positivity was independently linked to an increased 28-day mortality risk.

As with false positive GM in serum30 (e.g. mucositis in patients after autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation) there are numerous possibilities of false positive GM in BALF, like infections with closely related fungi10 (e.g. Histoplasma capsulatum, Fusarium spp., Cryptococcus spp. and Penicillium spp.) or aspiration of enteral nutrition supplements15. To our knowledge, no study has systemically studied the impact of aspiration in critically ill patients as a potential source of false-positive GM in BALF.

Dysphagia is a well-known risk factor for aspiration and leads to an increased morbidity and mortality in ICU patients31. Depending on the patients screened and diagnostic tool used, up to 30% of ICU patients are diagnosed with dysphagia31,32. Higher age, tube feeding, sepsis and duration of mechanical ventilation are known risk factors for dysphagia32. In our own cohort, patients with aspiration were all mechanically ventilated over 10 days (a median of 249 h) and presented with an older age (> 10 years older than patients with pIPA), which are both common risk factor for dysphagia and aspiration33. In the NUTRIREA-2 trial34, the authors explored the impact of nutrition route (enteral vs. parenteral) on microaspiration in critically ill patients with shock in a mixed cohort of patients. Results showed that both ways of nutritional support led to high rates of microaspiration, although vomiting was significantly more common in the enteral feeding group (31% vs. 15%, p = 0.016). Because almost 90% of the included patients were admitted to the ICU because of a medical reason and only around 10% were admitted due to planned or urgent surgery, these results are not comparable to our study. Our cohort only included surgical patients. Most of these patients received both parenteral and enteral feeding simultaneously (data not shown). Therefore, it is not surprising that 24% of the patients included in our study showed signs of aspiration (and false-positive GM in BALF). The term “aspiration” is not clearly defined in the literature and no single theory has been accepted so far since it lacks clear definitions. The definition proposed in this manuscript by Mandell et al.35 is not the only definition but one that incorporates pathogenetic and predisposing factors and hence seemed to be the best available option. A recent review published by the Japanese Study Group on Aspiration Pulmonary Disease36 proposed clinical diagnostic criteria. This algorithm differed between “certain cases” (direct observation of aspiration) and “probable or suspected cases”, where swallowing function disorders were apparent in the latter diagnosis. This is very close to the diagnostic criteria used in our study.

Because we suspected the enteral nutritional supplements were responsible for the false-positive GM results, we tested several enteral supplements from different companies. Most interestingly, supplements with a high soy-based ratio showed higher GM values. Moreover, the GM values were slightly elevated in milk-protein-based supplements without soy. One reason might be that Aspergillus spp. were used in the fermentation process37. Galactomannan often contaminates the final solutions even after the filtration process10. Ansorg et al. already published over 20 years ago38 that vegetables, cereals and fruit contain components that react in the latex agglutination test The authors assumed that because of the specificity of the monoclonal antibody of the test, the components are probably GM and contamination. In recent reports, researchers have assumed that these contaminants enter the bloodstream through a disrupted gastrointestinal barrier (mucositis or graft-versus-host disease), resulting in false-positive GM serum test results. In our study, we did not directly test the BALF for the presence of nutritional components but assumed that some presence of nutritional supplements should have been the cause of false- positive GM BALF test results.

Only 1 of the 39 patients with aspiration showed a positive culture specimen for Aspergillus spp., even though GM in BALF was as high as 1.98 (IQR 1.25–4.32) and hence significantly higher than proposed by actual guidelines for GM cutoffs in BALF10. This finding supports our assumption that these patients presented with false-positive GM BALF test results. Nevertheless, 38% of patients with aspiration may have received an unnecessary antifungal therapy. This is worrisome because antifungal therapies with triazoles carry potential side effects in critically ill patients, like severe drug-drug interactions, dose-adjustment in severe kidney and liver failure, neurologic disturbances and QT prolongation39.

In summary, one can say that if there is clear evidence of aspiration, elevated GM values (independent of their maximum values) may not be linked to IPA. This is especially true in cases with missing risk factors such as glucocorticoid therapy. In our model, no use of corticosteroids together with a negative Aspergillus culture predicted a high probability of aspiration (Tjur’s R2 = 0.65). Nonetheless, even a positive Aspergillus culture specimen from BALF does not automatically reflect invasive Aspergillus growth, especially in the absence of abnormal medical imaging or appropriate signs and symptoms19.

Aspiration in patients with enteral nutritional supplements seems to be an important issue as a potential cause of false-positive GM BALF test results. Nevertheless, positive GM values (and other mycologic evidence of Aspergillus spp.) in BALF need to be seriously considered in critically ill patients. Interpretation should always involve the patient risk factors, including medical history underlying conditions and mycological results19.

Ethical statement

Statement of human rights: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were done in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee [approval by the institutional review board of the medical faculty of the University of Heidelberg, Germany (S-191/2018)] and with the declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent: The approval committee has waived informed consent.

Methods

Study design

This study was conducted retrospectively at a single surgical ICU at Heidelberg University Hospital, Heidelberg (Germany). Data were extracted from patients who were hospitalised between March 2014 and December 2019. Heidelberg University Hospital is a regional reference centre for SOT (especially kidney and liver). Informed consent was deemed unnecessary according to national regulations and due to the retrospective nature of the study. The presented protocol was approved by Institutional Review Board (IRB) (Ethics committee of the medical faculty, Heidelberg university hospital, Heidelberg, Germany: S-191/2018). In addition, the study was registered at the German Clinical Trials Register (DRKS-ID: DRKS00024735) as a secondary analysis of data published in 202322.

Patient population

Only adult (≥ 18 years) surgical ICU patients with at least one BALF sample with a GM ODI ≥ 1.0 according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Platelia™ Aspergillus enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay [ELISA], Bio-Rad, Marnes-la-Coquette, France) and one CT scan of the chest or chest X-ray were included in the study.

Patient data

Data were collected from an electronic medical record system (ISH®, SAP, Walldorf, Germany). The following items were extracted: underlying diseases (COPD, coronary artery disease, diabetes mellitus, heart insufficiency, liver cirrhosis, solid tumour, alcohol abuse, SOT, chemotherapy and history of stroke) and complications during the ICU stay (bacteraemia, need for dialysis, corticosteroid therapy and duration of mechanical ventilation). The American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification and the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score were collected to assess disease severity.

Outcomes

The primary endpoint was 28-day mortality (from any cause) after ICU admission. This endpoint was chosen due to fact, that major epidemiologic outcome studies in critical care patients chose the 28-day (or 30-day) mortality endpoint1,40. This makes our results comparable to other outcome studies in the intensive care setting.

Definitions

(p)IPA

IPA was defined according to the AspICU criteria (Table S1). According to Schröder et al.41 in addition to AspICU criteria, a GM ODI ≥ 1.0 in BALF samples also served as an entry criterion for IPA diagnosis. Patients fulfilling all four criteria (clinical data + radiological findings + host factors + mycological finding) were termed putative IPA (pIPA).

Aspiration

Aspiration was defined when either “definitive” or “probable” aspiration occurred during an ICU stay, triggering a bronchoscopy from the responsible staff. “Definitively aspirated” was defined as vomiting and/or documented aspiration. “Probably aspirated” (Fig. 2) was defined based on anamnesis, reported of BAL and chest CT/X-ray and documented risk factors for aspiration according to Mandell et al.35: signs and symptoms of impaired swallowing (documentation of impaired swallowing, operation due to oesophageal cancer, delirium, COPD, dementia, Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, intubation and tracheostoma); signs of impaired consciousness (history of stroke or reanimation); and a high probability that the gastric content reaches the lungs (documented reflux over the nasal-gastric tube or enteral feeding through the nasal-gastric tube).

Second-line antifungal therapy

The decision to add a new antifungal agent or to switch to another antifungal drug was driven by mycological evidence (e.g. direct [cultured] or indirect [GM] evidence of Aspergillus spp.) in BALF, radiological evidence (e.g. ongoing radiological evidence of IPA on chest CT/X-ray) or clinical evidence (e.g. a decrease in the respiratory status despite ongoing antifungal therapy).

Corticosteroid therapy

Corticosteroid therapy was defined as the use of prednisolone > 20 mg/day or another corticosteroid at an equivalent dosage during or before the hospital stay prior to the first GM detection in BALF.

Microbiology

Aspergillus spp. isolates, grown from respiratory specimen isolates, were investigated at the Department of Medical Microbiology and Hygiene, Bacteriology Division of University Hospital Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany. Only positive cultures with Aspergillus spp. were included in the study. GM testing was performed with the Platelia™ Aspergillus ELISA (Bio-Rad). Microbial growth in blood culture bottles was detected as described by Dubler et al.22.

BAL

BAL for invasively ventilated or awake patients was performed according to a local standardised protocol, which has been described in detail in a previous study22.

Statistics

The data was stored in Excel (Microsoft®, Redmond, WA, USA) and then analysed in R (cite with: R Core Team (2022). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL https://www.R-project.org/.) using the packages survminer (Alboukadel Kassambara, Marcin Kosinski and Przemyslaw Biecek (2021). survminer: Drawing Survival Curves using ‘ggplot2’. R package version 0.4.9. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=survminer) and survival (Therneau T (2021). _A Package for Survival Analysis in R_. R package version 3.2–13, < URL: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=survival>.) for survival analysis and gtsummary (https://doi.org/10.32614/RJ-2021-053) to display the data in tables. Continuous data are presented as the mean and standard deviation. Categorical variables are displayed as absolute and relative frequencies. The Mann–Whitney U-test or the chi-square test was used to calculate potential differences between the groups. Kaplan–Meier curves present survival information. Cox proportional hazards regression model with adjustment for potential confounders was used to identify risk factors for mortality (hazard ratio [HR]). Two-sided p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses.

Data availability

Data are available only on request. Please use the following contact information from the author: simon.dubler@uk-essen.de.

References

Vincent, J. L. et al. International study of the prevalence and outcomes of infection in intensive care units. JAMA 302, 2323–2329. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2009.1754 (2009).

Quenot, J. P. et al. The epidemiology of septic shock in French intensive care units: The prospective multicenter cohort EPISS study. Crit. Care 17, R65. https://doi.org/10.1186/cc12598 (2013).

Organization, W. H. WHO fungal priority pathogens list to guide research, development and public health action (2022).

De Pauw, B. et al. Revised definitions of invasive fungal disease from the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Invasive Fungal Infections Cooperative Group and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group (EORTC/MSG) Consensus Group. Clin. Infect. Dis. 46, 1813–1821. https://doi.org/10.1086/588660 (2008).

Koulenti, D., Garnacho-Montero, J. & Blot, S. Approach to invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in critically ill patients. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 27, 174–183. https://doi.org/10.1097/QCO.0000000000000043 (2014).

Shi, C. et al. Incidence, risk factors and mortality of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in patients with influenza: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mycoses 65, 152–163. https://doi.org/10.1111/myc.13410 (2022).

White, P. L. et al. A national strategy to diagnose coronavirus disease 2019-associated invasive fungal disease in the intensive care unit. Clin. Infect. Dis. 73, e1634–e1644. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa1298 (2021).

Blot, S. I. et al. A clinical algorithm to diagnose invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in critically ill patients. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med. 186, 56–64. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201111-1978OC (2012).

Prattes, J. et al. Risk factors and outcome of pulmonary aspergillosis in critically ill coronavirus disease 2019 patients-a multinational observational study by the European Confederation of Medical Mycology. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 28, 580–587. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2021.08.014 (2022).

Mercier, T. et al. Defining galactomannan positivity in the updated EORTC/MSGERC consensus definitions of invasive fungal diseases. Clin. Infect. Dis. 72, S89–S94. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa1786 (2021).

Townsend, L. & Martin-Loeches, I. Invasive aspergillosis in the intensive care unit. Diagnostics 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics12112712 (2022).

Liu, W. D. et al. False-positive aspergillus galactomannan immunoassays associated with intravenous human immunoglobulin administration. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 26, 1555. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2020.02.002 (2020).

Steinmann, J., Buer, J. & Rath, P. M. Caspofungin: Cross-reactivity in the aspergillus antigen assay. J. Clin. Microbiol. 48, 2313. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.00118-10 (2010).

Lheureux, O. et al. False-positive galactomannan assay in broncho-alveolar lavage after enteral nutrition solution inhalation: A case report. JMM Case Rep. 4, e005116. https://doi.org/10.1099/jmmcr.0.005116 (2017).

Tomita, Y., Sugimoto, M., Kawano, O. & Kohrogi, H. High incidence of false-positive aspergillus galactomannan test results in patients with aspiration pneumonia. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 57, 935–936. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02238.x (2009).

Murashige, N., Kami, M., Kishi, Y., Fujisaki, G. & Tanosaki, R. False-positive results of aspergillus enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays for a patient with gastrointestinal graft-versus-host disease taking a nutrient containing soybean protein. Clin. Infect. Dis. 40, 333–334. https://doi.org/10.1086/427070 (2005).

Bassetti, M. et al. EORTC/MSGERC definitions of invasive fungal diseases: Summary of activities of the Intensive Care Unit Working Group. Clin. Infect. Dis. 72, S121–S127. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa1751 (2021).

Ledoux, M. P., Guffroy, B., Nivoix, Y., Simand, C. & Herbrecht, R. Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 41, 80–98. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0039-3401990 (2020).

Blot, S., Rello, J. & Koulenti, D. Diagnosing invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in ICU patients: Putting the puzzle together. Curr. Opin. Crit. Care 25, 430–437. https://doi.org/10.1097/MCC.0000000000000637 (2019).

Schauwvlieghe, A. et al. Invasive aspergillosis in patients admitted to the intensive care unit with severe influenza: A retrospective cohort study. Lancet Respir. Med. 6, 782–792. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30274-1 (2018).

Koehler, P. et al. Defining and managing COVID-19-associated pulmonary aspergillosis: The 2020 ECMM/ISHAM consensus criteria for research and clinical guidance. Lancet Infect. Dis. 21, e149–e162. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30847-1 (2021).

Dubler, S. et al. Impact of Invasive Pulmonary aspergillosis in critically Ill Surgical patients with or without solid organ transplantation. J. Clin. Med. 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12093282 (2023).

Dubler, S. et al. Effect of Dexamethasone on the incidence and outcome of COVID-19 Associated Pulmonary aspergillosis (CAPA) in critically ill patients during first- and second pandemic Wave-A single Center experience. Diagnostics 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics12123049 (2022).

Tortorano, A. M. et al. Invasive fungal infections in the intensive care unit: A multicentre, prospective, observational study in Italy (2006–2008). Mycoses 55, 73–79. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0507.2011.02044.x (2012).

Lewis, R. E. & Kontoyiannis, D. P. Invasive aspergillosis in glucocorticoid-treated patients. Med. Mycol. 47(Suppl 1), S271–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/13693780802227159 (2009).

Latge, J. P. & Chamilos, G. Aspergillus Fumigatus and aspergillosis in 2019. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 33. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00140-18 (2019).

Michel, S. et al. Targeting the granulocytic defense against A. Fumigatus in healthy volunteers and septic patients. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24129911 (2023).

Gioia, F., Walti, L. N., Orchanian-Cheff, A. & Husain, S. Risk factors for COVID-19-associated pulmonary aspergillosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Respir. Med. 12, 207–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(23)00408-3 (2024).

Group, R. C. et al. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 384, 693–704. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2021436 (2021).

Rachow, T. et al. Case report: False positive elevated serum-galactomannan levels after autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation caused by oral nutritional supplements. Clin. Case Rep. 4, 505–508. https://doi.org/10.1002/ccr3.516 (2016).

Zuercher, P., Moret, C. S., Dziewas, R. & Schefold, J. C. Dysphagia in the intensive care unit: Epidemiology, mechanisms, and clinical management. Crit. Care 23, 103. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-019-2400-2 (2019).

Zuercher, P. et al. Dysphagia incidence in intensive care unit patients with coronavirus disease 2019: Retrospective analysis following systematic dysphagia screening. J. Laryngol. Otol. 136, 1278–1283. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022215122001517 (2022).

Zuercher, P. et al. Risk factors for Dysphagia in ICU patients after invasive mechanical ventilation. Chest 158, 1983–1991. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2020.05.576 (2020).

Nseir, S. et al. Impact of nutrition route on microaspiration in critically ill patients with shock: A planned ancillary study of the NUTRIREA-2 trial. Crit. Care 23, 111. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-019-2403-z (2019).

Mandell, L. A. & Niederman, M. S. Aspiration pneumonia. N. Engl. J. Med. 380, 651–663. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1714562 (2019).

Ueda, A. & Nohara, K. Criteria for diagnosing aspiration pneumonia in Japan—A scoping review. Respir. Investig. 62, 128–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resinv.2023.11.004 (2024).

Dowdells, C. et al. Gluconic acid production by aspergillus terreus. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 51, 252–257. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1472-765X.2010.02890.x (2010).

Ansorg, R., van den Boom, R. & Rath, P. M. Detection of aspergillus galactomannan antigen in foods and antibiotics. Mycoses 40, 353–357. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0507.1997.tb00249.x (1997).

Boyer, J., Feys, S., Zsifkovits, I., Hoenigl, M. & Egger, M. Treatment of invasive aspergillosis: How it’s going, where it’s heading. Mycopathologia 188, 667–681. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11046-023-00727-z (2023).

Bassetti, M. et al. A multicenter study of septic shock due to candidemia: Outcomes and predictors of mortality. Intensive Care Med. 40, 839–845. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-014-3310-z (2014).

Schroeder, M. et al. Comparison of four diagnostic criteria for invasive pulmonary aspergillosis-A diagnostic accuracy study in critically ill patients. Mycoses 65, 824–833. https://doi.org/10.1111/myc.13478 (2022).

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.D. designed the study and wrote the manuscript. M.E. acquired most of the data and revised the manuscript. C.L. revised the manuscript. T.B. drafted the manuscript and substantially revised it. S.Z. helped to interpret microbiological data. P.S. helped to interpret microbiological data. B.B. supported statistical analysis. F.R. acquired and interpreted radiological data. P.K. acquired radiological data. Y.L.H. acquired and interpreted data. M.W. designed the study and helped to interpret the data. All authors have approved the submitted version and agreed both to be personally accountable for the author’s own contributions and to ensure that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work, even ones in which the author was not personally involved, are appropriately investigated, resolved, and the resolution documented in the literature.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Additional information with conflict-of-interest statement: Paul Schnitzler, Bettina Budeus, Yuan Lih Hoo, Fabian Rengier, Michael Etringer, Christoph Lichtenstern, Paulina Kalinowska and Stefan Zimmermann declare no conflict of interest. Simon Dubler received research funding from Stiftung Universitätsmedizin Essen (Essen, Germany). Simon Dubler received honoraria for lectures from Akademie für Infektionsmedizin e.V. Thorsten Brenner received grants from Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG), Dietmar Hopp Stiftung, Stiftung Universitätsmedizin Essen and Innovationsfonds des Gemeinsamen Bundesausschusses (G-BA). Thorsten Brenner received honoraria for lectures from CSL Behring GmbH, Schöchl medical education GmbH, Biotest AG, Baxter Deutschland GmbH, Boehringer Ingelheim Pharma GmbH, Astellas Pharma GmbH, B. Braun Melsungen AG, MSD Sharp & Dohme GmbH, Daiichi Sankyo Deutschland GmbH, Akademie für Infektionsmedizin e.V., Lücke Kongresse GmbH, Pfizer Deutschland GmbH, MVZ Labor Dr. Limbach & Kollegen GbR. TB pending patents with BRAHMS GmbH. Thorsten Brenner participation on advisory board with Baxter Deutschland GmbH and Bayer AG. Markus A. Weigand received grants from DFG-Graduate school and DZIF-TIARA Cohort. Markus A. Weigand received consulting fees from MSD, Mundipharma, Gilead, Pfizer, Shionogi, Eumedica, Coulter, Biotest, Sedana, SOBI and Böhringer. Markus A. Weigand received honoraria for lectures from MSD, Pfizer and Gilead. MAW pending patents on EPA / 25.10.17 / EPA 17198330, Delta like ligand for diagnosing severe infections. Markus A. Weigand leadership role in DSG and PEG.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dubler, S., Etringer, M., Lichtenstern, C. et al. Implications for the diagnosis of aspiration and aspergillosis in critically ill patients with detection of galactomannan in broncho-alveolar lavage fluids. Sci Rep 15, 1997 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85644-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85644-5