Abstract

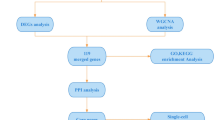

Obesity (OB) and atherosclerosis (AS) represent two highly prevalent and detrimental chronic diseases that are intricately linked. However, the shared genetic signatures and molecular pathways underlying these two conditions remain elusive. This study aimed to identify the shared diagnostic genes and the associated molecular mechanism between OB and AS. The microarray datasets of OB and AS were obtained from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) analysis and the weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) were conducted to identify the shared genes. Then least absolute shrinkage selection (LASSO) algorithm was used for diagnostic genes discovery. The diagnostic genes were validated using expression analysis and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves. Furthermore, Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was used to investigate molecular pathways and immune infiltration related to the diagnostic genes. TF-gene and miRNA-gene networks were also constructed by utilizing the NetworkAnalyst tool. By intersecting the key module genes of WGCNA with DEGs in OB and AS, 56 shared genes with the same expression trend were identified. Using LASSO algorithm, we obtained two shared diagnostic genes, namely SAMSN1 and PHGDH. Validation confirmed their expression patterns and robust predictive abilities. GSEA revealed the crucial roles of SAMSN1 and PHGDH in disease-associated pathways. Additionally, higher immune cell infiltration expression was found in both diseases and strongly linked to the diagnostic genes. Finally, we constructed the TF-gene and miRNA-gene networks. We identified SAMSN1 and PHGDH as potential diagnostic genes for OB and AS. Our findings provide novel insights into the molecular underpinnings of the OB-AS link.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

OB is a complex, multi-factor chronic metabolic disease primarily characterized by excessive accumulation of body fat and weight increase1. It has reached pandemic levels worldwide. According to the World Health Organization, more than 1.9 billion adults were overweight in 2016, with over 650 million classified as obese2. OB is a major risk factor for numerous health problems, including type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, certain cancers, musculoskeletal disorders, and respiratory conditions3. The adverse health effects of OB are largely mediated by metabolic and inflammatory alterations associated with excess adiposity4. Excess fat deposition, particularly in visceral organs, leads to insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, chronic low-grade inflammation, and oxidative stress5,6. These OB-related disorders can directly or indirectly impact the structure and function of various organ systems, ultimately increasing the risk of comorbidities and mortality7.

AS is a progressive inflammatory disorder characterized by the accumulation of lipids, inflammatory cells, and fibrous elements within the arterial wall8. It is the primary underlying cause of cardiovascular diseases, including myocardial infarction, stroke, and peripheral artery disease, which collectively account for nearly one-third of global deaths annually9. The development of atherosclerotic lesions involves a complex interplay of endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress, lipid accumulation, and chronic inflammation10,11.

Numerous large-scale epidemiological studies have consistently demonstrated a strong positive correlation between OB and the incidence and severity of AS and its clinical manifestations12. Mechanistic studies support this association, suggesting that OB-induced alterations, such as adipose tissue inflammation, insulin resistance, and dyslipidemia, may contribute to endothelial dysfunction and accelerate the atherogenic process13. However, a comprehensive understanding of the shared genetic signatures and regulatory networks underlying the OB-AS connection remains elusive. Identifying common diagnostic genes and dissecting the shared pathways involved in the pathogenesis of these two conditions could provide important insights into their comorbidity and inform the development of more effective diagnostic and therapeutic strategies.

In this study, we performed an integrated bioinformatics analysis leveraging transcriptome datasets from clinical samples of obese, atherosclerotic, and healthy individuals. Our research provides a comprehensive overview of the potential molecular links between OB and AS, offering valuable insights into the shared diagnostic biomarkers and underlying pathological mechanisms. The findings from this study may guide future experimental investigations and contribute to the development of novel diagnostic and therapeutic interventions targeting the comorbidity of OB and AS.

Methods

Data selection

The datasets related to OB and AS were retrieved from GEO (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo). GSE151839 (OB), GSE44000 (OB), GSE2508 (OB), GSE28829 (AS), GSE100927 (AS), and GSE57691 (AS) were selected for bioinformatic analysis. Details of GEO datasets used in the study were shown in Table 1. Among them, GSE151839 and GSE44000 were used as discovery cohorts for the OB, and GSE28829 and GSE100927 were regarded as discovery cohorts of AS. Besides, GSE2508 and GSE57691 were the validation cohort of OB and AS, respectively. The details of these datasets were consolidated in Table 1. Using “sva” R package (version 3.50.0) to remove the batch effects, GSE151839 and GSE44000 were combined into a new dataset, which contained 17 normal samples and 17 obese samples. Besides, GSE44000 and GSE10092 were also combined into a new dataset, which included 48 normal samples and 85 atherosclerotic samples. Principal component analysis (PCA) was used to assess whether the batch effect was eliminated.

Differential gene expression analysis

The Limma package (version 3.58.1) was used to identify DEGs between two groups. “Adjusted P value < 0.05 and |Fold Change| > 1.5” were defined as the threshold for identifying the DEGs. Heatmaps and volcano plots were generated using the R packages pheatmap (version 1.0.12) and ggplot2 (version 3.5.1), respectively.

WGCNA analysis

WGCNA (version 1.72-5) is an algorithm to cluster genes into different modules and investigate the relationships between modules and disease14. The “pickSoftThreshold” function was employed to determine the optimal soft-power threshold to construct a weighted adjacency matrix, which was then transformed into the topological overlap matrix. A hierarchical clustering dendrogram was constructed and similar gene expressions were divided into different modules. Finally, the modules that were strongly associated with clinical traits were identified.

Functional enrichment analysis

The WebGestalt platform (https://www.webgestalt.org/) was employed to perform gene functional enrichment analysis. P-value < 0.05 was defined as the criteria of significant terms. The top 10 significantly enriched GO and pathway terms were selected for analysis.

Screening of candidate diagnostic genes by LASSO

LASSO is a machine learning method that considers both the goodness of fit of regression coefficients and the absolute magnitude of those coefficients for significant variables selection15. We used the “glmnet” package (version 4.1-8)in R to perform LASSO analysis to investigate the potential candidate genes for the diagnosis of OB and AS.

Curve analysis of ROC

ROC analysis was carried with R package “pROC” (version 1.18.5) to assess the diagnostic values of the diagnostic genes. Area under the curve (AUC) was calculated to determine the sensitivity and accuracy of the diagnostic genes in the obese and atherosclerotic dataset.

Single-gene GSEA

Single-gene GSEA was performed to investigate the possible roles of hub genes using the “clusterProfiler” package (version 4.10.1). All samples were divided into high-expression and low-expression groups based on the median of the prognostic genes, and GSEA was conducted to explore the enrichment of KEGG pathways in different groups. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Immune cells infiltration analysis

Single-sample GSEA (ssGSEA) in the “GSVA” R package was used to analyze the immune infiltration of OB and AS. The correlation between infiltrating immune cells and prognostic genes expression was then calculated using Spearman’s correlation.

Prediction the association between TFs, miRNAs and genes

TF-gene and miRNA-gene networks were constructed by utilizing the NetworkAnalyst tool (http://www.networkanalyst.ca/). The TF-gene network was constructed by JASPAR database. The miRNA-gene network was established using miRTarBase database.

Statistical analysis

We utilized R software (version 4.3.2) for all data analyses. Differences between two groups were analyzed using Student’s t-test or the Wilcoxon test. Furthermore, correlation analyses were conducted using Pearson correlation analysis. GraphPad Prism software (version 9) was used for plotting the images, with P < 0.05 as the threshold of significance for all statistical analyses.

Results

Identification of DEGs in OB and AS

Before the bioinformatic analysis, we tested the batch effects of the obese and atherosclerotic groups and found that the batch effects of the two diseases were apparent (Fig. 1A, B). The data after batch correction were presented in Fig. 1C and D, which reflected that the batch effect of the merged data has been eliminated. The “limma” R package was applied to identify DEGs between the two groups. In the obese dataset, 1171 DEGs were identified, comprising 743 up-regulated and 428 down-regulated genes. In the atherosclerotic dataset, 1052 DEGs were identified, with 719 up-regulated and 333 downregulated genes (Table S1). The volcano maps were used to show the expression pattern of DEGs in both diseases (Fig. 2A, C), and the heat maps demonstrated top 100 DEGs of the two diseases (Fig. 2B, D).

Discovery of DEGs in OB and AS. (A) Volcano plot of DEGs in the obese dataset created by merging GSE151839 and GSE44000. (B) Heatmap presenting the top 100 DEGs in the obese dataset. (C) Volcano plot of DEGs in the atherosclerotic dataset created by merging GSE28829 and GSE100927. (D) Heatmap presenting the top 100 DEGs in the atherosclerotic dataset.

WGCNA network construction and module identification

To explore the potential correlation between the diseases and key genes, we performed WGCNA. A power of β = 5 was used for both obese and atherosclerotic dataset to ensure the creation of a scale-free network (Fig. 3A, B). A total of 10 modules were identified in obese dataset, and 7 modules were identified in atherosclerotic dataset (Fig. 3C, D). To identify the genes related to the progression of both diseases, we analyzed the association between the modules and clinical phenotypes. For OB, the turquoise module had the strongest correlation (|r| = 0.76, P < 0.001) (Fig. 3E). For AS, the turquoise module showed the strongest correlation (|r| = 0.72, P < 0.001) (Fig. 3F, Table S2).

Identification of shared genes and functional enrichment analysis

The intersection of the genes screened by differential expression analysis and WGCNA in OB and AS was drawn by a Venn diagram, and 71 intersection genes were obtained (Fig. 4A). Then 56 genes after excluding genes with opposite expression trends in two datasets were selected for further analysis (Table S3). The WebGestalt platform was used to perform gene functional enrichment analysis of these genes. The GO analysis showed that the shared genes were related to catecholamine metabolic process, catechol-containing compound metabolic process, and B cell activation (Fig. 4B). The pathway functional analysis showed that these genes were involved in thiamine metabolic pathways, IL1 and megakaryocytes in OB, and leptin signaling pathway (Fig. 4C).

Discovery of the common diagnostic genes through LASSO algorithm

To further identify candidate diagnostic genes with a significant characteristic value for classifying the disease and control groups, LASSO algorithm was used based on the above 56 shared genes. In the obese group, the LASSO regression algorithm identified 6 potential candidate genes with a substantial impact on the diagnosis (Fig. 5A, B). Similarly, the LASSO algorithm identified 21 featured genes in the atherosclerotic group (Fig. 5C, D). Details of the LASSO results of OB and AS can be found in Table S4. Finally, SAMSN1 and PHGDH were chosen as the common diagnostic gene after intersecting the candidate genes in OB and AS (Fig. 5E).

The screening of obese and atherosclerotic diagnostic genes using LASSO algorithm. (A) LASSO coefficient profiles of diagnostic genes in obese dataset. (B) Ten cross-validation to select the optimal parameter log (λ) in obese dataset. (C) LASSO coefficient profiles of diagnostic genes in atherosclerotic dataset. (D) Ten cross-validation to select the optimal parameter log (λ) in atherosclerotic dataset. (E) Venn diagram showing the overlapping diagnostic genes in obese and atherosclerotic dataset.

Candidate biomarker expression level and diagnostic value

Next, we analyzed the SAMSN1 and PHGDH expression levels in the two datasets. Compared to normal groups, SAMSN1 expressed higher both in the obese (P < 0.001) and atherosclerotic groups (P < 0.001) (Fig. 6A, E), while PHGDH had lower expression in both diseases (Fig. 6B, F). Next, ROC analysis was performed to evaluate the specificity and sensitivity of the two diagnostic genes. The results for the obese biomarkers were favorable, with SAMSN1 (AUC = 0.927) (Fig. 6C) and PHGDH (AUC = 0.938) (Fig. 6D) exhibiting robust predictive performance. Similarly, in the atherosclerotic group, SAMSN1 (AUC = 0.788) (Fig. 6G) and PHGDH (AUC = 0839) (Fig. 6H) showed reliable predictive capabilities.

Expression pattern and diagnostic value of SAMSN1 and PHGDH. (A,B) Expression of SAMSN1 (A) and PHGDH (B) in the OB’s dataset. (C,D) ROC curve of SAMSN1 (C) and PHGDH (D) in the OB’s dataset. (E,F) Expression of SAMSN1 (E) and PHGDH (F) in the AS’s dataset. (G,H) ROC curve of SAMSN1 (G) and PHGDH (H) in the AS’s dataset.

Validation of the diagnostic genes’ expression

Next, we validated the expression of these two diagnostic genes in external datasets. Results showed that SAMSN1 expression was elevated in both the obese and atherosclerotic groups compared to normal groups, whereas PHGDH expression was lower in both conditions (Fig. 7A-D).

Single-gene GSEA of the diagnostic genes

To further identify the potential enriched regulatory pathways involved of the two diagnostic genes, we conducted single-gene GSEA analysis of SAMSN1 and PHGDH in obese and atherosclerotic datasets. Enrichplot was used to show the top 5 activating and inhibiting pathways for each gene in two disease groups. In obese dataset, the two genes were mainly involved in metabolic pathways such as citrate cycle, fatty acid metabolism, pyruvate metabolism and propanoate metabolism (Fig. 8A, B). In atherosclerotic dataset, these genes were mainly enriched in muscle contraction and cardiomyopathy (Fig. 8C, D).

Immune infiltration analysis

We further investigated the difference in immune infiltration in both diseases. The proportion of immune cells was shown as a bar plot in each group. Compared with the normal samples, α-DC, B cells, cytotoxic cells, DC, iDC, Macrophages, Mast cells, Neutrophils, T cells and Th1 cells were all increased in both two diseases (Fig. 9A, B). Moreover, the relationships between the diagnostic genes and immune cell proportions were investigated. In obese samples, SAMSN1 expression was significantly positively correlated with macrophages and Th1 cells, while negatively correlated with Th17 cells. However, PHGDH expression showed a positive correlation with Th17 cells and negative correlation with B cells, cytotoxic cells and macrophages (Fig. 9C). In atherosclerotic samples, SAMSN1 expression was significantly positively correlated with macrophages and neutrophils, while negatively correlated NK cells. PHGDH expression had a positive correlation with NK cells and negative correlation with macrophages (Fig. 9D). These results showed that immune function is crucial to the development of OB and AS.

Immune infiltration analysis of OB and AS. (A) Comparison of immune infiltration between normal control and obese patients. (B) Comparison of immune infiltration between normal control and atherosclerotic patients. (C) Correlation between SAMSN1 and PHGDH expression and immune cells in the obese dataset. (D) Correlation between SAMSN1 and PHGDH expression and immune cells in the atherosclerotic dataset.

Gene regulatory network construction

Finally, we constructed the gene regulatory networks highlighting the key transcription factors (TFs) and microRNAs (miRNAs) that potentially mediate the crosstalk between OB and AS. The TF-gene network contained 13 nodes and 13 edges. SAMSN1 and PHDGH were regulated by 7 and 6 TFs, respectively. FOXC1 and YY1 were found to interact with both SAMSN1 and PHDGH. Further, putative sites between key TFs and diagnostic genes were predicted with relative profile score threshold 90% using JASPAR database (Table S5). On the other hand, the miRNA-gene network contained 68 nodes and 69 edges (Fig. 10A). SAMSN1 and PHDGH were regulated by 24 and 45 miRNAs respectively. Hsa-mir-124-3p, hsa-mir-7-5p and hsa-mir-101-3p were found to interact with both SAMSN1 and PHDGH (Fig. 10B). Details of the regulatory gene-miRNA networks obtained can be found in Table S6.

Discussion

Emerging evidence increasingly supports the notion that the pathogenesis of AS shares significant characteristics with OB, particularly in the context of insulin resistance, a common metabolic dysfunction. Insulin resistance not only affects glucose metabolism but also plays a crucial role in lipid metabolism and inflammatory responses, both of which are central to the development of AS16. Notably, obesity can exacerbate the progression of AS through various mechanisms, including the secretion of pro-inflammatory adipokines and the accumulation of visceral fat, which is closely associated with cardiovascular risk17,18. Moreover, these two conditions often coexist, creating a vicious cycle that further complicates treatment and management strategies for affected individuals. While there is substantial research focused on OB and AS individually, there is a noticeable gap in studies examining their common molecular mechanisms. Thus, it is imperative to understand the link between OB and AS.

Through integrated bioinformatic approaches combining differential expression analysis, WGCNA, and LASSO regression, we identified the shared molecular signatures between OB and AS, highlighting SAMSN1 and PHGDH as potential diagnostic biomarkers for both conditions. Furthermore, GSEA revealed that the co-pathogenesis of these diseases was rooted in the abnormal metabolism of various metabolites linked to the tricarboxylic acid cycle. This disruption led to the aberrant activation of immune cells and an exaggerated immune response in affected individuals. Collectively, our findings on these novel diagnostic genes and the underlying molecular mechanisms offered new clinical insights for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with OB and AS.

SAMSN1 is a member of a novel gene family characterized by putative adaptors and scaffold proteins containing SH3 and SAM domains19. Although the direct relationship between SAMSN1 and OB or AS has not been fully established, emerging studies suggest its potential involvement in the pathogenesis of other diseases, including certain cancers and neurological disorders20,21. On the other hand, PHGDH encodes the enzyme 3-phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase, which plays a crucial role in the serine biosynthesis pathway22. This pathway is essential for producing serine, an important amino acid involved in protein synthesis and other biomolecular processes. Disruptions in the PHGDH gene can lead to serine deficiency disorders and have been implicated in various cancers due to its regulatory role in regulating cellular metabolism23. A study reported that liver hepatocyte-specific PHDGH KO mice showed a notable weight increase and impaired systemic glucose metabolism, underscoring its importance in metabolic regulation24. Further investigation is warranted to clarify the mechanism of SAMSN1 and PHDGH in diagnosing OB and AS.

Chronic inflammation, driven by immune cell infiltration, plays a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of both OB and AS25. This inflammation is not merely a consequence of these conditions but is integral to their development. To explore this, we employed ssGSEA to compare the immune cell infiltration between the normal and disease groups. In OB, the expansion of adipose tissue is associated with the recruitment of various immune cell types, including macrophages, neutrophils, and different lymphocyte populations. These infiltrating cells secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines that promote insulin resistance and sustain an inflammatory environment26. Similarly, in AS, monocyte-derived macrophages and T cells are pivotal mediators of lesion formation. Macrophages accumulate oxidized lipids, transforming into foam cells, a hallmark of early atherosclerotic plaques27. Additionally, effector T cells such as Th1 and Th17 subsets infiltrate the arterial intima, amplifying pro-inflammatory signaling and plaque progression28. The complex interplay among metabolic disturbances, lipid accumulation, and immune dysregulation propagates chronic inflammation, fueling the development and complications of both OB and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

Additionally, our study constructed comprehensive gene regulatory networks that integrate TFs and miRNAs, which are crucial for mediating the molecular crosstalk between OB and AS. These networks serve as a framework to elucidate how dysregulated gene expression contributes to the pathophysiology of both conditions. Within this network, several key TFs and miRNAs were identified as potential master regulators that orchestrate the expression of shared dysregulated genes and pathways prevalent in OB and AS. Identifying these key regulators provides valuable insights into the potential mechanisms underlying the connection between OB and AS.

However, there are still some limitations in our study. Our results were based on the bioinformatic analysis, and there were not enough experimental data to confirm our results. Besides, the exact mechanisms of metabolic disorders mediated by SAMSN1 and PHGDH need further investigation. Therefore, our results still need to be verified through in vivo and in vitro studies. Nonetheless, this comprehensive analysis lays a solid foundation for future research aimed at unraveling the intricate relationship between OB and AS, ultimately paving the way for more personalized and effective management of these interconnected conditions.

Data availability

Publicly available datasets used in this study can be downloaded from the GEO database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author..

Code availability

The relevant code used in this study is available at https://github.com/180861/Bioinformatics-code.git.

References

Tchernof, A. & Després, J. P. Pathophysiology of human visceral obesity: an update. Physiol. Rev. 93, 359–404 (2013).

Mohanty, S. S. & Mohanty, P. K. Obesity as potential breast cancer risk factor for postmenopausal women. Genes Dis. 8, 117–123 (2021).

Perdomo, C. M., Cohen, R. V., Sumithran, P., Clément, K. & Frühbeck, G. Contemporary medical, device, and surgical therapies for obesity in adults. Lancet (London England) 401, 1116–1130 (2023).

Villarroya, F., Cereijo, R., Gavaldà-Navarro, A., Villarroya, J. & Giralt, M. Inflammation of brown/beige adipose tissues in obesity and metabolic disease. J. Intern. Med. 284, 492–504 (2018).

Ahmed, B., Sultana, R. & Greene, M. W. Adipose tissue and insulin resistance in obese. Biomed. Pharmacother. 137, 111315 (2021).

Neeland, I. J., Poirier, P. & Després, J. P. Cardiovascular and metabolic heterogeneity of obesity: Clinical challenges and implications for Management. Circulation 137, 1391–1406 (2018).

De Lorenzo, A. et al. Why primary obesity is a disease? J. Transl. Med. 17, 169 (2019).

Frostegård, J. Immunity, atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease. BMC Med. 11, 117 (2013).

Libby, P. et al. Atherosclerosis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 5, 56 (2019).

Belce, A., Ozkan, B. N., Dumlu, F. S., Sisman, B. H. & Guler, E. M. Evaluation of oxidative stress and inflammatory biomarkers pre and post-treatment in new diagnosed atherosclerotic patients. Clin. Exp. Hypertens. 44, 320–325 (2022).

Weber, C. & Noels, H. Atherosclerosis: current pathogenesis and therapeutic options. Nat. Med. 17, 1410–1422 (2011).

Csige, I. et al. The impact of obesity on the cardiovascular system. J. Diabetes Res. 2018, 3407306 (2018).

Lovren, F., Teoh, H. & Verma, S. Obesity and atherosclerosis: mechanistic insights. Can. J. Cardiol. 31, 177–183 (2015).

Langfelder, P. & Horvath, S. WGCNA: an R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinform. 9, 559 (2008).

Friedman, J., Hastie, T. & Tibshirani, R. Regularization paths for generalized Linear models via Coordinate Descent. J. Stat. Softw. 33, 1–22 (2010).

Di Pino, A. & DeFronzo, R. A. Insulin resistance and atherosclerosis: implications for insulin-sensitizing agents. Endocr. Rev. 40, 1447–1467 (2019).

Reardon, C. A. et al. Obesity and insulin resistance promote atherosclerosis through an IFNγ-Regulated macrophage protein network. Cell. Rep. 23, 3021–3030 (2018).

Silveira Rossi, J. L. et al. Metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular diseases: going beyond traditional risk factors. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 38, e3502 (2022).

Jiang, W., Ma, C., Bai, J. & Du, X. Macrophage SAMSN1 protects against sepsis-induced acute lung injury in mice. Redox Biol. 56, 102432 (2022).

Noll, J. E. et al. SAMSN1 is a tumor suppressor gene in multiple myeloma. Neoplasia (New York NY) 16, 572–585 (2014).

Sierksma, A. et al. Novel Alzheimer risk genes determine the microglia response to amyloid-β but not to TAU pathology. EMBO Mol. Med. 12, e10606 (2020).

Shen, L. et al. PHGDH inhibits ferroptosis and promotes malignant progression by upregulating SLC7A11 in bladder Cancer. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 18, 5459–5474 (2022).

Wang, K. et al. PHGDH arginine methylation by PRMT1 promotes serine synthesis and represents a therapeutic vulnerability in hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Commun. 14, 1011 (2023).

Hamano, M. et al. Hepatocyte-specific phgdh-deficient mice culminate in mild obesity, insulin resistance, and enhanced vulnerability to protein starvation. Nutrients 13 (2021).

Hulsmans, M., De Keyzer, D. & Holvoet, P. MicroRNAs regulating oxidative stress and inflammation in relation to obesity and atherosclerosis. FASEB J. 25, 2515–2527 (2011).

Kawai, T., Autieri, M. V. & Scalia, R. Adipose tissue inflammation and metabolic dysfunction in obesity. Am. J. Physiol. Cell. Physiol. 320, C375–C391 (2021).

Chistiakov, D. A., Melnichenko, A. A., Myasoedova, V. A., Grechko, A. V. & Orekhov, A. N. Mechanisms of foam cell formation in atherosclerosis. J. Mol. Med. 95, 1153–1165 (2017).

Chistiakov, D. A., Sobenin, I. A. & Orekhov, A. N. Regulatory T cells in atherosclerosis and strategies to induce the endogenous atheroprotective immune response. Immunol. Lett. 151, 10–22 (2013).

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank the researchers who uploaded their data to the GEO database.

Funding

This work was supported by Traditional Chinese Medicine Science and Technology Project of the State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine (GZY-KJS-2023-023), Shandong Provincial TCM science and technology project (Q-2023189), and Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation (No. ZR2023QH495).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Guoxia Li and Yunsheng Xu conceived the study idea. Wenrong An and Kegong Tang performed the data analysis. Juan Liu and Wenfei Zheng participated in the preparation of figures and tables. Wenrong An wrote the manuscript. Kegong Tang revised the manuscript. All authors approved the submitted version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

An, W., Tang, K., Liu, J. et al. Exploration of the shared diagnostic genes and molecular mechanism between obesity and atherosclerosis via bioinformatic analysis. Sci Rep 15, 2301 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85825-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85825-2