Abstract

Duddingtonia flagrans is a nematode-trapping fungus that is widely used to control parasitic nematodes in livestock. After oral ingestion and passage through the digestive tract of animals, this microorganism captures nematodes in feces. Although many researchers have examined the safety of this fungus for humans, animals, and the environment, few reports have discussed the safety of nematode-trapping D. flagrans biologics for animals. In this study, D. flagrans safety was tested, while adverse effects and toxicities were examined in sheep. First, the nematode killing effects in naturally parasitized sheep after administration of lyophilized D. flagrans preparations were tested.lyophilized D. flagrans preparations were administered to sheep at various doses, followed by key blood factor monitoring and an examination of major tissues, organ lesions, and pathology. Lastly, lyophilized D. flagrans preparations were administered to sheep at various doses, followed by key blood factor monitoring and an examination of major tissues, organ lesions, and pathology. the nematode killing effects of naturally parasitized sheep after administration were tested. The results demonstrated that treatment with D. flagrans isolates significantly reduced developing larvae numbers in feces, with an efficiency of 92.99%. Lyophilized preparations had no observable effects on physiological parameters in sheep, thus indicating a wide safety range in target animals, with potentially minimal risks in veterinary clinical practice. Overall, D. flagrans freeze-dried biologics effectively helped to controlled parasitic infections, which are safe in animals like sheep, and thus may provide a practical platform for nematode-trapping fungi in veterinary clinical settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Currently, to biologically control parasites in livestock, anthelmintic drugs are widely applied but the misuse of these drugs has led to serious resistance issues; therefore, new control measures must be researched and developed1. One of the most important approaches is the exploitation of natural enemies, including predatory fungi that prevent and control parasites2. Predatory fungi are widely distributed in soils and exist in many ecosystems, from tropical areas to cold Antarctica and from terrestrial to aquatic ecosystems3.

Based on their discovery, considerable research efforts have been directed toward predatory fungi, their predatory properties, biochemical mechanisms, and clinical applications4. For example, the nematode-predatory fungus Duddingtonia flagransgenerates large numbers of thick-walled spores, which can pass through animal digestive tracts without inactivation in clinical use, and then germinate in feces5. With recognized predatory roles, D. flagrans then targets a variety of parasitic nematodes, such as Osertagia spp., Nematodirus, and Strongyloides stercoralis. More recently, Mendes et al. demonstrated that a solution of D. flagransconidia was effective in vitro against gastrointestinal nematodes in buffaloes when used alone and/or in association with ivermectin6. In Voinot et al., the daily administration of nutritional pellets enriched with M. circinelloides and D. flagrans spores, for a prolonged interval (2 years), prevented helminth infection (C. daubneyiand gastrointestinal nematodes) in dairy cattle under rotational grazing7. Critically, predatory activities increase with increased larvae numbers, thus the fungus has broad application values8,9,10,11,12. However, there is a dearth of information on predatory fungi safety profiles in target animals13. In a recent study, edible gelatins were desiccated and tested on captive bison maintained in a zoological garden under continuous pasturing. Lyophilized D. flagranspreparations had no effects on physiological parameters in bison14. Recently, Braga et al.15 demonstrated the efficacy and safety of Bioverm®, a commercial product based on D. flagrans chlamydospores (AC001), available in Brazil for the integrated control of helminth infections in farm animals. Despite the scientific efficiency and proven safety of D. flagrans(AC001) by oral administration, no reports have yet assessed possible harmful effects during gastrointestinal transit. Long-term clinical and anatomical-pathological studies on heifers fed parasitic fungal pellets on a daily basis were performed and showed no side-effects or specific lesions. Moreover, the risk of heifers being infected with trematodes was reduced and their health was improved16.

Duddingtonia flagrans has been positively developed as a biological agent in the United States, Sweden, and New Zealand for controlling parasitic nematodes15. Biological control with the predacious fungi D. flagrans still remains a promising free-living parasite regulator alternative for use in livestock17. To control ruminant parasitic nematodes, several studies examining D. flagrans as a biological control agent have shown excellent results18,19. The main advantages of D. flagrans include fewer resistance problems, a fully natural product, and environmentally friendly. To characterize potential primary and clinical applications, predatory D. flagranssafety profiles were examined in our study in target animals, with a view to their becoming widely accepted lyophilized biological agents1. Our study lays the foundation for future clinical applications and commercial production, and provides a reference for future in-depth predatory fungi studies.

Materials and methods

Fungal strain

A test strain of D. flagrans strain CIM1 (NCBI bio-sample accession number: SAMN05504105), was obtained from the Veterinary Parasite Laboratory of the Inner Mongolia Agricultural University, Hohhot, Inner Mongolia, China. D. flagrans was inoculated onto Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) (Beijing Landbridge, China) medium until the mycelium covered the dish surface16, then it was cut into 0.5 cm × 0.5 cm squares, added to a new dish, and incubated for 1 week at 25 °C. Next, the mycelium was cut into 0.5 cm × 0.5 cm squares and transferred to corn kernel medium at 25 °C for 3 weeks. Spore eluate was prepared by adding 1 mL Tween-80 to 500 mL of water, and then heating it to 121℃ for 15 min. Spores were eluted several times from the medium using spore eluent and then filtered on an ultra-clean bench. Samples then underwent vacuum freeze drying until a dry powder was obtained. We determined chlamydospore counts in the lyophilized formulation to be 2.13 × 108 chlamydospores/g. The Bottle were then sealed with sealing film, and stored at 4℃.

Animals

D. flagrans use in controlling helminth parasites

Experimental sheep (n = 30) were naturally infected with gastrointestinal nematodes on farms in Siziwang Banner, Ulanqab, Inner Mongolia, China, and had not been previously dewormed within 6 months of the trial. The Animal Experimentation Ethics Committee followed Chinese National Standard Laboratory Animal-Guidelines for the ethical review of animal welfare (GB/T 35892 − 2018). All animal protocols were reviewed by the Animal Experiments Ethics Committee at Inner Mongolia Agricultural University.

Animal safety experiments

The animal safety test site was located in the animal house of Inner Mongolia Agricultural University. 3–4 month old sheep were selected (n = 9). At 10 days before the trial, albendazole (99% purity; Kangmu Animal Pharmaceutical, China) was orally administered once. Ivermectin (99% purity; Kangmu Animal Pharmaceutical, China). was also subcutaneously injected for 3 consecutive days according to body weight, to ensure the absence of helminth infections.

Methods

In vivo efficacy of D. flagrans on nematode eggs and larvae in sheep feces

Thirty Small Tailed Han Sheep, 6 ~ 8 months old, and approximately 50 kg were randomly selected. Rectal feces were collected and examined for nematode infection. Ten sheep with a similar number of EPG infections were divided into groups, including ivermectin, D. flagrans biologic, and blank control groups. The D. flagrans group dose was 1 × 106chlamydospores/kg body weight (bw)20. Egg numbers per gram (EPG) and larvae per gram (LPG) of feces were measured and collected before and 1 week after the trial. Eggs in feces were counted using a modified McMaster technique to calculate EPG. Fecal samples were incubated at a constant temperature of 25 °C for 15 days. After this period, third-stage non-predatory larvae (L3) were isolated using the modified Baermann’s method21. Mean EPG and LPG values in groups were compared before and after dosing to determine D. flagrans effectiveness in controlling parasites.

In vivo safety experimental tests

Nine sheep with an average body weight = 18 kg were randomly divided into 5-fold dose (5 × 106 chlamydospores/kg bw), 10-fold dose (1 × 107 chlamydospores/ kg bw), and blank control groups. Each group consisted of three sheep, and corresponding doses were applied based on bw. Suspensions were administered as a single dose on an empty stomach by perfusion with a syringe.

Clinical observations

During trials, multiple key parameters were observed in sheep every day, including behavioral disorders, food and drink appetite, jaundice, respiratory rate, cough, neurological signs, diarrhea, edema, and developmental status. Behavioral disorders referred to excitement, depression, restlessness, and other abnormalities. Defecation represented constipation and diarrhea. During trials, sheep were fed high-quality alfalfa three times a day (morning, noon, and night).

Body temperature and weight measurements

Oral D. flagrans biological effects on body mass and weight gain were examined by weighing sheep before the trial and at days3, 7, 15, and 30 after dosing. Measurements were taken between 9 am and 10 am. on an empty stomach.

Routine blood tests

Blood samples were collected for routine blood tests at 3 days before the trial and then at days15 and 30 after dosing. The following biomarkers were measured using an automatic animal blood cell analyzer: WBC, Lym, Mon, Neu, Eo, Ba, RBC, MCV, Hct, MCHC, Hb, and MPV.

Organ histomorphology

At study end, all test sheep were euthanized according to ethical regulations. Euthanasia was conducted by intravenously injecting animals with phenobarbital (90 mg/kg body weight). This was formulated in accordance with Laboratory Animal-Guidelines for Euthanasia by the People’s Republic of China (GB/T39760-2021). The sheep dissected, and the abdominal cavity cut open to check for fluids or blood in the cavity. All soft ribs on the left side were cut using bone cutters, and ribs on left and right sides were broken by hand to expose the entire thoracic cavity to observe pleural colors and bleeding/adhesions. The following organs and tissues were checked by visual inspection: brain, cerebellum, kidney, heart, pancreas, liver, spleen, lung, stomach, ileum, jejunum, colon, cecum, and lymph nodes. All gross pathological lesions were photographed and recorded. The heart, liver, spleen, lungs, and kidneys were then taken fur further examinations. Excess connective tissue around organs was carefully peeled away and surface fluids blotted with filter paper before weighing and recording data. To calculate organ coefficients, the following equation was used: organ weight (g)/body weight (g) × 100%.

Statistical analysis

Experimental data were processed as the mean ± standard deviation, and ANOVA was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 22 software. Data were analyzed for normal distributions using Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Levene’ s tests. If variance was unevenly distributed, equivalent non-parametric tests (primarily Kruskal–Wallis analysis of variance) were used. A P < 0.05 value was considered significant.

Results

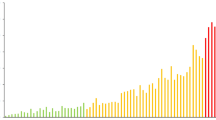

Nematode predation efficiency in feces after oral biologic administration

Mean EPG and LPG values in group were compared before and after dosing to determine the parasite effects of biologic agents. After treatment, fungi significantly reduced LPG development in feces. As shown (Table 1), results from ivermectin and D. flagrans biologic groups were significantly different (P < 0.05) when compared with the control group, while the D. flagrans group showed better effectiveness than the ivermectin group in terms of significant effects.

Clinical observations

One sheep in the 10-fold dose group had coughing symptoms, which was recovered within 48 h without treatment. Other sheep showed no abnormal changes in terms of respiration, spirit, appetite, or feces during the trial.

Body temperature and weight measurements

All body temperatures were within normal ranges except for one sheep, which was outside the range. However, no statistical differences were observed between dose groups at 3, 7, 15 and 30 days when compared with the pre-dose period (Table 2). Body weights in all groups increased, however, weight gain differences in groups before the trial and at days 7, 15, and 30 after the trial were not statistically significant (Table 3).

Pathological changes in sheep

No fluids were found in thoracic or abdominal cavities in any sheep. Similarly, no abnormal contents, abnormal position, or organ shape were discovered; and no dislocation, adhesion, torsion, or rupture changes were recorded. The shape, color, size, and texture of the heart, liver, spleen, lungs, kidneys, brain, and other organs were normal and were without bleeding, scar formation, nodules, or necrosis. Pancreas size, texture, and color were normal. Intestinal duct plasma membrane surfaces were normal in color, without adhesion, parasitic nodules, tumors, or hemorrhages. All pathological sections were normal (Fig. 1).

Routine blood test results

Routine blood biomarkers from the dose groups were within normal ranges before the trial and at days 15 and 30 after dosing. Differences between groups were not significant (Table 4).

Blood biochemistry results

Blood biochemical parameters were within normal ranges for each dose group before the trial and at days 15 and 30 after dosing. Differences between groups were not significant (Table 5).

Organ coefficients

The heart, liver, spleen, lungs, and kidney organs were weighed at autopsy and organ coefficients calculated for all sheep. There was no significant difference in organ coefficients between the experimental groups (Table 6).

Discussion

In this work, D. flagrans was shown to exert considerable predatory effect on fecal larvae in in vivo experiments. In 2011, Paz-Silva et al. examined D. flagrans predation efficiency on infective roundworm cyathostomin larvae and identified a 94% reduction in larvae, while D. flagransactivity increased with egg and larvae numbers in co-culture11. Ferreira et al. also examined the same predation efficiency on L3 after passing through the digestive tracts of rabbits pigs, and showed that L3 reductions in feces were 81.33%8. Wang showed a reduction of up to 100% in larvae numbers in feces when lyophilized D. flagransbiologic preparations were used in combination with anthelmintic drugs22. The number of L3 fecal co-cultures decreased substantially in sheep grazing in The Netherlands after treatment with D. flagransspores, but no differences were observed between EPGs, but severe haemonchosis occurs also in treated group23. Similarly, in a field study on three farms in Switzerland, co-cultured larval development was significantly inhibited but fecal EPGs were not significantly affected during D. flagransfeeding24. The fungal treatment group in this study significantly reduced LPG development in feces, but EPG did not show an effect, similar to our results. When D. flagranscame into contact with larval worms, they adhered to and immobilized them, allowing the fungus to penetrate cell walls and feed on the contents4. D. flagranscan also produce chlamydospores, which are a type of thick-walled resting spore25. This allows the fungus to maintain high environmental tolerance and pass through gastrointestinal tracts of grazing livestock without reducing germination rates or predation efficiency. The literature has reported that D. flagranschlamydospores can withstand gastrointestinal transportation and other undesirable environments to germinate, forming a predator-based, three-dimensional network structure that captures living larvae in feces15. Therefore, the continuous use of D. flagrans reduces infective larvae in pastures and has great potential to control reinfection by nematodes. These studies also suggested that D. flagrans had good validity in in vitro predatory activity, consistent with our observations. While the effectiveness of D. flagrans predation efficiency and its clinical application is undoubted, its safety profiles in target animals have been rarely reported.

In 2020, at the request of the European Commission, Bampidis et al. examined D. flagranssafety and predation efficiency (as a feed) and stated that it did not irritate the skin or eyes, but was sensitive to the respiratory tract26. No conclusions were drawn on its skin-sensitizing potential. In our study, after oral 5- and 10-fold D. flagrans administrative doses to sheep, we observed that preparations had no effects on key clinical traits, such as respiration, mental status, appetite, and fecal excretion in groups. After extensive measurements, only one sheep had a body temperature of up to 40℃, while the remainder were within normal ranges. The normal body temperature of a sheep is in the 38.3–39.9 °C range, and capture stress can cause a 0.5–1 °C increase in temperature during measurements. One sheep had coughing symptoms at blood collection, which were fully recovered after 48 h without treatments. Moreover, heavy rain occurred in Hohhot the day before symptom onset and the temperature dropped dramatically. Coughing symptoms were probably related to the cool weather, and no abnormalities were found after hematological analysis, which was not sufficient to indicate that the preparation influenced the normal physiological indicators of the sheep. Necropsy techniques allowed for a more thorough visual inspection of lesions in different organs and tissues in animals, which are vital when studying different drug effects on an organism. Autopsy results showed that no abnormal changes had occurred in organs and tissues and that pathological sections were normal. Organ coefficient values are commonly used in toxicological studies and in our study, organ coefficient differences between groups were not significant when compared with the control group. The safety profiles of lyophilized D. flagrans in sheep have shown that this agent has the potential for use in clinical and commercial applications.

The following study limitations were encountered. First, D. flagransstrains have enzymatic activity and can produce serine proteases27 which help improve feed digestibility and utilization in animals, and fungi have been found to be effective in degrading complex compounds in several studies28. But this needs to be further verified. Second, we did not assess whether D. flagranssecondary metabolites were carried into animal products and exerted effects on consumers. Third, in clinical applications, researchers have hypothesized that nematode-predatory fungi are not harmful to the environment and are safe. However, in recent years, these fungi have been reported to affect rotifer populations and density levels (rotifers improve wastewater quality during biological treatment)29,30. Similarly, high numbers of nematode-predatory fungi can endanger rotifer populations and therefore it is vital that in-depth studies examining nematode-predatory fungi effects on certain organisms in other environments are conducted. We observed that D. flagrans had some nematode repellent effects and were better than control drug effects. Our results provide a new strategy to control veterinary parasites in China, and also new reference data for studying plant-derived insecticidal active substances.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Fiałkowska, E., Fiałkowski, W. & Pajdak-Stós, A. The relations between predatory fungus and its rotifer preys as a noteworthy example of intraguild predation (IGP). Microb. Ecol. 79, 73–83 (2020).

Luns, F. D. et al. Coadministration of nematophagous Fungi for biological control over nematodes in bovine in the South-Eastern Brazil. Biomed Res. Int. 2018, 1–6 (2018).

Silva, A. R. et al. Biological control of sheep gastrointestinal nematodiasis in a tropical region of the southeast of Brazil with the nematode predatory fungi Duddingtonia flagrans and Monacrosporium thaumasium. Parasitol. Res. 105, 1707–1713 (2009).

Zhang, W., Liu, D., Yu, Z., Hou, B. & Wang, R. Comparative genome and transcriptome analysis of the nematode-trapping fungus duddingtonia flagrans reveals high pathogenicity during nematode infection. Biol. Control 143, 104159 (2020).

Tabata, A. C. et al. Biological control of gastrointestinal nematodes in horses fed with grass in association with nematophagus fungi Duddingtonia flagrans and Pochonia Chlamydosporia. Biol. Control 182, 105219 (2023).

Mendes, L. Q. et al. In vitro association of Duddingtonia flagrans with ivermectin in the control of gastrointestinal nematodes of water buffaloes. Rev. MVZ Cordoba 27, 3 (2022).

Voinot, M. et al. Integrating the control of helminths in dairy cattle: deworming, rotational grazing and nutritional pellets with parasiticide fungi. Vet. Parasitol. 278, 109038 (2020).

Ferreira, S. R., de Araújo, J. V., Braga, F. R., Araujo, J. M. & Fernandes, F. M. In vitro predatory activity of nematophagous fungi Duddingtonia flagrans on infective larvae of Oesophagostomum spp. after passing through gastrointestinal tract of pigs. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 3, 1589–1593 (2011).

Araujo, J. M. et al. Control of Strongyloides westeri by nematophagous fungi after passage through the gastrointestinal tract of donkeys. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 21, 157–60 (2012).

Braga, F. R. et al. Destruction of Strongyloides venezuelensis infective larvae by fungi Duddingtonia flagrans, Arthrobotrys robusta and Monacrosporium sinense. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 44, 389–391 (2011).

Paz-Silva, A. et al. Ability of the fungus Duddingtonia flagrans to adapt to the cyathostomin egg-output by spreading chlamydospores. Vet. Parasitol. 179, 277–282 (2011).

Hiura, E. et al. Fungi predatory activity on embryonated Toxocara canis eggs inoculated in domestic chickens (Gallus gallus Domesticus) and destruction of second stage larvae. Parasitol. Res. 114, 3301–3308 (2015).

Voinot, M. et al. Control of Strongyles in first-season grazing ewe lambs by integrating deworming and thrice-weekly administration of parasiticidal fungal spores. Pathogens 10, 1338 (2021).

Salmo, R. et al. Formulating parasiticidal Fungi in dried edible gelatins to reduce the risk of infection by Trichuris Sp. among continuous grazing bison. Pathogens 13, 82 (2024).

Braga, F. R., Ferraz, C. M., da Silva, E. N. & de Araújo, J. V. Efficiency of the Bioverm® (Duddingtonia flagrans) fungal formulation to control in vivo and in vitro of Haemonchus Contortus and Strongyloides papillosus in sheep. Biotech10, 62 (2020).

Voinot, M. et al. Safety of daily administration of pellets containing parasiticidal fungal spores over a long period of time in heifers. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 32, 1249–1259 (2021).

Buzatti, A. et al. Duddingtonia flagrans in the control of gastrointestinal nematodes of horses. Exp. Parasitol. 159, 1–4 (2015).

Mendoza-de Gives, P. Soil-borne nematodes: Impact in agriculture and livestock and sustainable strategies of prevention and control with special reference to the use of nematode natural enemies. Pathogens 11, 640 (2022).

Souza, D. C. et al. Compatibility study of Duddingtonia flagrans conidia and its crude proteolytic extract. Vet. Parasitol. 322, 110030 (2023).

Healey, K., Lawlor, C., Knox, M. R., Chambers, M. & Lamb, J. Field evaluation of Duddingtonia flagrans IAH 1297 for the reduction of worm burden in grazing animals: Tracer studies in sheep. Vet. Parasitol. 253, 48–54 (2018).

Wang, B. B. et al. In vitro and in vivo studies of the native isolates of nematophagous fungi from China against the larvae of trichostrongylides. J. Basic Microbiol. 7, 265–275 (2017).

Wang, W. R. Study on the clinical application model of nematode-trapping fungus-Duddingtonia flagrans (Master’s thesis of Inner Mongolia Agricultural University, 2018).

Eysker, M. et al. The impact of daily Duddingtonia flagransapplication to lactating ewes on gastrointestinal nematodes infections in their lambs in the Netherlands. Vet. Parasitol. 41, 91–100 (2006).

Faessler, H., Torgerson, P. R. & Hertzberg, H. Failure of Duddingtonia flagrans to reducegastrointestinal nematode infections in dairy ewes. Vet. Parasitol. 147(1-2), 96–102 (2007).

Simon, A., Theodor, P. P. & Wolfgang, H. HTSeq—A Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics 2, 166–169 (2015).

EFSA Panel on Additives and Products or Substances used in Animal Feed (FEEDAP) et al. Safety and efficacy of BioWorma® (Duddingtonia flagrans NCIMB 30336) as a feed additive for all grazing animals. EFSA J.18, e06208 (2020).

Braga, F. R. et al. Interaction of the nematophagous fungus Duddingtonia flagrans on Amblyomma cajannense engorged females and enzymatic characterisationof its chitinase. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 23, 584–594 (2013).

Kazda, M., Langer, S. & Bengeelsdorf, F. R. Fungi open new possibilities for anaerobicfermentation of organic residues. Energy Sustain. Soc. 4, 6 (2014).

Pajdak-Stosa, A., Wazny, R. & Fiałkowska. E. Can a predatory fungus (Zoophagus sp.) endanger the rotifer populations in activated sludge? Fungal Ecol. 23, 75–78 (2016).

Crook, E. K. et al. Prevalence of anthelmintic resistance on sheep and goat farms in the mid-atlantic region and comparison of in vivo and in vitro detection methods. Small Ruminant Res. 143, 89–96 (2016).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.M., L.J. and Z.F. conceived the study. Y.M., Z.L., Y.Z. and Q.L. performed the experiments. Y.M., Z.L., L.H., H.L. and R.W. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors have read and approved thefinal version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

The studies involving animals were reviewed and approved by Inner Mongolia Agricultural University of Ethics Committee. All animal protocols followed Animal Experimentation Ethics Committee regulations of the Inner Mongolia Agricultural University.

Informed consent

Informed consent was not required as the study did not involve human participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ma, Y., Jiang, L., Fan, Z. et al. Nematode controlling effects and safety tests of Duddingtonia flagrans biological preparation in sheep. Sci Rep 15, 1843 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85844-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85844-z