Abstract

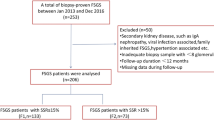

Glomerular endothelial cells (GECs) are pivotal in developing glomerular sclerosis disorders. The advancement of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) is intimately tied to disruptions in lipid metabolism. Sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P), a molecule transported by high-density lipoproteins (HDL), exhibits protective effects on vascular endothelial cells by upregulating phosphorylated endothelial nitric oxide synthase (p-eNOS) and enhancing nitric oxide (NO) production. Nevertheless, the abundance of S1P within HDL in individuals with FSGS and minimal change disease (MCD) is yet to be elucidated, and its defensive role in GECs necessitates empirical confirmation. A total of 14 FSGS patients, 16 MCD patients, and 16 healthy controls (NC) were included in the study, with FSGS and MCD confirmed by renal biopsy. After blood sample collection, HDL was isolated and categorized into intact HDL, phospholipid-depleted HDL(apo-HDL), phospholipid-remained HDL(phoHDL), and recombinant HDL (rHDL). Various HDL samples, comprising intact, apo-HDL, pho-HDL and rHDL, were co-cultivated with human renal glomerular endothelial cells (HRGECs). Western blotting was utilized to quantify p-eNOS levels and assess PI3K-AKT pathway activation. Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analyzed S1P concentrations, while real-time quantitative PCR evaluated the expression of enzymes involved in S1P metabolism. Fluorescence labeling methods measured NO levels, and an immunofluorescence colocalization assay investigated Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1 (S1PR1) expression in GECs across distinct kidney tissue groups. The HDL from FSGS patients demonstrated a significantly enhanced ability to promote p-eNOS expression and NO release in HRGECs compared to MCD patients and healthy controls. Additionally, the synthesis activity of S1P in renal tissues of FSGS patients was markedly higher than that observed in MCD patients and healthy controls, suggesting that S1P may play a crucial protective role in the progression of FSGS. Immunofluorescence staining showed that compared with MCD and NC, the expression of S1PR1 in GECs of FSGS patients was significantly decreased. Recombinant HDL with added S1P promoted the increase of p-eNOS in HRGECs. Knockdown of S1PR1 using siRNA reduced the expression of p-eNOS and NO release. The mechanism underlying the regulation of p-eNOS expression by rHDL was associated with the PI3K-AKT signaling pathway. The enhanced presence of S1P on HDL could serve as a diagnostic marker to differentiate FSGS from MCD. Incorporating S1P into HDL enhances glomerular endothelial cell function, suggesting that the S1P/S1PR pathway might offer a promising therapeutic avenue for FSGS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Minimal change disease (MCD) and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) are two primary manifestations of idiopathic nephrotic syndrome, each characterized by distinct pathological features1. Differentiating between FSGS and MCD can often be challenging due to the focal nature of scar tissue and the limitation of tissue sampling techniques. However, the two conditions are associated with different therapeutic strategies and prognostic outcomes. Typically, MCD does not progress to end-stage renal disease (ESRD), whereas FSGS is recognized as the leading cause of ESRD resulting from primary glomerular disease2. Therefore, it is imperative to investigate alternative methodologies for distinguishing between these two conditions and examine the underlying mechanisms contributing to their differences.

While podocytes and mesangial cells have been extensively studied for their roles in the pathogenesis of FSGS, recent research also highlights the early involvement of dysfunctional GECs. The dysfunction in GEC dysfunction contributes to podocyte injury and mesangial cell activation, ultimately leading to the progression of glomerulosclerosis3.In contrast, in MCD, the absence of pathological changes in GECs and the resulting glomerular vascular sclerosis may serve as a potential distinguishing feature between these two conditions.

HDLs play a pivotal role in the transport of cholesterol from peripheral tissues to the liver, thereby maintaining cholesterol homeostasis. Additionally, HDLs exhibit a range of protective effects on endothelial cells, such as antioxidant, anti-apoptotic, anti-inflammatory, anti-thrombotic, and anti-proteolytic activities. Notably, they enhance vasodilation through the production of nitric oxide (NO), underscoring their importance in vascular health4. Nephrotic syndrome can significantly alter the structure and function of HDLs5. However, there is no relevant research on how the structure and function of HDL in FSGS patients change and what impacts they have on the disease.

Sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) is a bioactive lysophospholipid that regulates a wide array of vital cellular functions. HDLs serve as the primary and vehicle for S1P, transporting approximately 60% of the total S1P content in plasma, thereby playing a pivotal role in its distribution and circulation6. Upon binding to its receptors (S1PR1-5), S1P triggers various G-protein-mediated intracellular signaling cascades, resulting in a spectrum of cellular responses. Among endothelial cells, S1PR1 is the most abundantly expressed receptor, followed by S1PR2 and S1PR37. S1P exerts endothelial protection by activating eNOS, which subsequently prompts the generation of NO within endothelial cells8.

In the context of FSGS and MCD, alterations in S1P content within HDL and their subsequent effects on GECs remain poorly understood. This study aims to investigate and validate these alterations through experimental research.

Methods

Participant recruitment

Patient recruitment and sample collection methods were taken reference from our recently published study, where patients with MCD and FSGS were diagnosed through renal biopsy while excluding other potential diseases9. The baseline characteristics, including the lipid profiles of patients in each group, are presented in Supplementary Table 1. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval from the Ethics Committee of Fujian Medical University Union Hospital (Fujian, China, 2023QH020). Prior to participation, informed consent was obtained to ensure voluntary agreement and full understanding.

Cell culture

Human renal glomerular endothelial cells (HRGECs), procured from ScienCell Research Laboratories (Carlsbad, CA, USA), were cultured in an endothelial cell-specific medium formulated with 5% fetal bovine serum, 1% endothelial cell growth factor supplement, and 1% antibiotic-antimycotic solution, all components supplied by the same laboratory. Cells were kept in a controlled environment at 37 °C, fully humidified, and gassed with 5% CO2 and 95% air to ensure optimal growth conditions.

Isolation, selective delipidation, and reconstitution of HDL

HDL was isolated according to established protocols10. Blood samples from NC (N), FSGS patients (F), and MCD patients (M) were collected in EDTA-coated tubes. LDL (density: 1.019–1.063 g/ml) and HDL (density: 1.063–1.210 g/ml) fractions were isolated from pooled plasma via ultracentrifugation at 550,000 g for 5 h at 4 °C. HDL was further purified through dialysis against sterile PBS over three days in a dark, 4 °C setting to remove contaminants. HDL purity was verified by 12% SDS-PAGE, and its concentration was precisely quantified using an apoA-I-specific assay kit (Solarbio, SEKH-0093, Beijing, China), and adjusted to 30 µg/mL for subsequent experiments. N-HDL refers to HDL from NC, and F-HDL refers to HDL from FSGS patients.

Professor Zheng’s reported method11 was adopted for selective lipid removal. In brief, HDL was mixed with diisopropyl ether in a 1:2 ratio and agitated for 24 h at 4 °C, followed by centrifugation to isolate phoHDL (containing proteins and phospholipids) in the aqueous layer. Alternatively, HDL was treated with a butanol-diisopropyl ether blend (40:60) at a 1:2 ratio and agitated for 30 min at room temperature to obtain apoHDL (solely proteinaceous HDL) in the aqueous phase. Both fractions were filtered before use. To prepare recombinant high-density lipoproteins (rHDL) for subsequent uses, S1P was incorporated into N-HDL at the desired concentration, followed by overnight rotation at 4 °C to ensure proper integration12.

To evaluate the efficiency of delipidation and the purity of different HDL fractions, non-targeted mass spectrometry analysis was performed on apo-HDL and pho-HDL samples. The results showed that apo-HDL samples had significantly lower levels of HDL’s key lipid components, including phospholipids and cholesterol, compared to pho-HDL, confirming the effectiveness of the delipidation process. The composition of HDL fractions was normalized based on apoA-I concentration. Detailed mass spectrometry data are presented in Supplementary Excel file named ‘purity identification of apoHDL and pho-HDL’.

S1P detection by UPLC-MS/MS

HDL-associated S1P levels were quantitated utilizing the established technique13. In essence, serum samples were combined with 50 µL of the internal standard C17-sph (1000 µg/L) and then precipitated using a methanol-to-sample ratio of 1:4. After centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 15 min, the clear supernatant was collected for UPLC-MS/MS analysis. Each sample was prepared uniquely for two LC/MS methodologies. For positive ion mode analysis, specific aliquots were introduced onto a Waters ACQUITY Premier HSS T3 Column (1.8 μm, 2.1 mm ID x 100 mm length). The mobile phase was composed of 0.1% formic acid in water (solvent A) and 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile (solvent B). The elution gradient initially started at 5% B, gradually increasing to 20% B in 2 min, then ramped up to 60% B over 3 min, followed by a swift rise to 99% B within 1 min, which was maintained for 1.5 min. Afterward, the mobile phase was rapidly returned to 5% B within 0.1 min and held for 2.4 min to stabilize the column. Throughout the analysis, the column was maintained at 40 °C, the flow rate was set to 0.4 mL/min, and the injection volume was 4 µL. For the negative ion mode analysis, a separate aliquot was prepared using the identical elution gradient as for the positive ion mode. Representative examples of primary and secondary spectra are provided in Supplementary Figure S1-2.

RNA isolation and real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

Eight 5-µm paraffin sections were excised from the renal biopsy wax blocks of patients with FSGS, MCD, and adjacent renal tissues resected due to renal tumor, respectively. Total RNA extraction was performed using the paraffin-embedded tissue total RNA extraction kit (Tiangen, Beijing, China). The NanoDrop One (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) was utilized to determine the total RNA content. Reverse transcription and RT-qPCR were performed with the reverse transcription and RT-qPCR kit (Sangon, Shanghai, China). Real-time quantitative PCR was conducted using the ABI 7500 system (Applied Biosystems, MA, USA). Relative gene expression levels were calculated using the 2-∆∆Ct method. GAPDH was used as the internal control, The primer sequences used in this study are provided in the supplementary Table 2.

Western blotting

Cultured cell proteins were extracted with RIPA buffer (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Abmole, Houston, USA). Protein levels were measured using a BCA kit (Solarbio, Beijing, China).Equal amounts of protein were electrophoresed on 7.5% gels and transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore, MA, USA). The membranes underwent blocking and overnight incubation with primary antibodies targeting Phospho-eNOS, eNOS, Phospho-PI3K, PI3K, Phospho-Akt, Akt, and α-tubulin (Abmart, Shanghai, China). Subsequent washing steps were followed by secondary antibody application, enabling visualization of immunoreactive bands through chemiluminescence imaging (Bio-Rad, CA, USA). Band densitometry was quantitatively analyzed using ImageJ software (NIH), ensuring accurate quantification of protein expression and phosphorylation levels.

Cellular NO release assay

The intracellular NO release was quantitatively assayed using a fluorescent microscope and a NO-specific probe (DAF-FM DA, Beyotime, Shanghai, China). Cells were seeded at a density of 2 × 10^4 cells per well in 24-well plates and treated with distinct HDL types (F-HDL, N-HDL, apo-HDL, pho-DHL, rHDL) for 6 h. Following thorough washing with PBS, cells were incubated with the probe for 30 min to label intracellular NO. Fluorescence images were captured using a fluorescence microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) and semi-quantitatively analyzed with ImageJ software (NIH). Meanwhile, the nitrate/nitrite quantification assay kit (Cat. No.S0021S) provided by Beyotime Biotechnology was used to measure the amount of NO released in the culture supernatant. The detection data have been included in Supplementary Figure S3.

Immunofluorescence staining

Immunofluorescence staining of kidney tissue sections utilized a two-label, three-color detection kit (ImmunoWay, TX, USA). The protocol encompassed dewaxing, antigen retrieval, and blocking with peroxidase for 15 min at room temperature. Following three PBS washes, primary antibodies targeting S1PR1 (1:100, Abmart, Shanghai, China) and CD31 (1:200, Abmart, Shanghai, China) were applied at optimized concentrations. Next, secondary antibodies were administered per the manufacturer’s instructions. After additional PBS washes, nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (Beyotime, Shanghai, China). Fluorescent images were then captured using the fluorescence microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany).

Statistical analysis

All experiments were conducted in triplicate to ensure reproducibility. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM), unless otherwise specified. Statistical comparisons were performed in one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), using the GraphPad Prism software 8.0. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

HDL in FSGS has the potential to enhance the expression of p-eNOS and NO release in HRGECs, in contrast to MCD and NC

To explore the distinct impacts of HDL on GECs across FSGS, MCD patients, and healthy individuals, we cocultured HDL samples from each group with HRGECs. Our observations revealed significant differences in HDL’s ability to regulate p-eNOS expression and NO production in HRGECs between the three groups (Fig. 1a-d and Supplementary Fig. S4). These findings suggest functional disparities between HDL from FSGS and MCD patients, particularly regarding their capacity to promote endothelial health within the context of their respective renal diseases.

HDL in FSGS enhances p-eNOS and NO release in HRGECs, contrasting MCD and NC. (a,b) Western blot analysis of p-eNOS level in HRGECs cocultured with various groups of HDLs at 30 µg/ml for 6 h. (c) The immunofluorescence images exhibit the intracellular NO levels across different cell groups, which have been detected utilizing a NO bioprobe (Scale bar: 100 μm). (d) A quantitative analysis of intracellular NO levels was using ImageJ.Statistical analysis using GraphPad Prism 8.0 software and employed One-way ANOVA to compare differences among multiple groups. Data presented as mean ± SEM, N = 3, with significance levels marked as *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. All experiments were replicated three times.

The ability of FSGS HDL to restore the protective function of HRGECs is attributed to its phospholipid composition

To control for differences in the lipid composition of HDL, lipid-removed HDL isolated from patients with FSGS and MCD was used to treat HRGECs. Notably, the lipid-removed HDL of FSGS (F- apoHDL) demonstrated a slightly stronger regulation of p-eNOS expression and NO release compared to the lipid-removed HDL of MCD (M-apoHDL). Both F-apoHDL and M-apoHDL exhibited a partial loss of their ability to upregulate p-eNOS expression and stimulate NO production (Fig. 2a-d and Supplementary Fig. S5a), indicating that these effects are partially mediated by lipid components rather than being solely attributable to protein.

FSGS-HDL restores HRGECs function due to its phospholipid composition. (a,b) Western blot analysis of p-eNOS level in HRGECs cocultured with various groups of apoHDLs at 30 µg/ml for 6 h. (c,d) The immunofluorescence images and quantitative analysis exhibit the intracellular NO levels across different cell groups, which have been detected utilizing a NO bioprobe. (e,f) Western blot analysis of p-eNOS level in HRGECs cocultured with various groups of pho-HDLs at 30 µg/ml for 6 h. (g,h) Using a NO-sensitive fluorescent probe, the intracellular NO expression in different cell groups was detected and analyzed (Scale bar: 100 μm). Data presented as mean ± SEM, with significance levels marked as *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Statistical analysis employed one-way ANOVA. All experiments were replicated three times.

To further investigate the influence of individual lipid components, we isolated apolipoprotein-rich HDL (phoHDL) from FSGS and MCD patients and incubated them with HRGECs. Interestingly, FSGS-derived phoHDL (F-phoHDL) reinstated the stimulatory effects on p-eNOS expression and NO production to levels similar to those observed with MCD-derived phoHDL (M-phoHDL) (Fig. 2e-h and Supplementary Fig. S5b). This observation underscores the pivotal role of phospholipids in mediating these responses in both FSGS and MCD contexts.

S1P levels are elevated in the lipid component of HDL in FSGS compared to MCD and NC

To assess plasma and HDL-associated S1P concentrations, we analyzed samples from 14 FSGS patients, 16 MCD patients, and 16 NC using UPLC-MS/MS. Given S1P’s preferential binding to HDL in plasma, we adjusted total plasma S1P levels by plasma HDL content to derive HDL-bound S1P levels. Notably, HDL-normalized S1P levels were significantly elevated in FSGS patients compared to MCD patients (Fig. 3a; FSGS vs. MCD: 229.5 ± 20.86 ng/mg vs. 148.4 ± 10.93 ng/mg; P < 0.01). While HDL-normalized S1P levels were slightly higher in MCD patients than NC, this difference did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 3a; MCD vs. NC: 148.4 ± 10.93 ng/mg vs. 140.8 ± 11.77 ng/mg; P > 0.05).

The levels and synthesis of S1P in FSGS are higher than MCD and NC. (a) S1P levels in HDL of various groups were measured by UPLC-MS/MS. (b) The enzymes involved in the synthesis and degradation of S1P were detected in renal tissues of different diseases using RT-qPCR. (c,d) The colocalization and expression of S1PR1 and CD31 were detected by Multiple immunofluorescence. IF showed that compared with MCD and NC patients, the expression of S1PR1 in GECs of FSGS patients was significantly decreased (scale bar: 50 μm). Data presented as mean ± SEM, N = 3, with significance levels marked as *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001,ns: non-significance. Statistical analysis employed one-way ANOVA. All experiments were replicated three times.

To evaluate the differential regulation of S1P synthesis in renal tissues of FSGS versus MCD, we isolated total RNA from each group and employed real-time qPCR to quantify the expression of key enzymes: sphingosine-1-phosphate lyase (SPL), sphingosine kinase 1/2 (SPHK1/2), and sphingosine-1-phosphate phosphatase 1/2 (SPP1/2). Our analysis revealed a prominent upregulation of SPHK1/2 in FSGS patients compared to MCD and NC, coupled with a conspicuous downregulation of SPL and SPP1/2 levels (Fig. 3b).

To investigate the potential causes of the activation of the S1P synthesis pathway, we employed immunofluorescence colocalization to assess the expression of S1PR1 in GECs. Immunofluorescence staining revealed that the expression of S1PR1 in GECs from patients with FSGS was significantly decreased compared to that in patients with MCD and NC patients (Nephrectomy due to benign renal tumor), the expression of S1PR1 in GECs of FSGS patients was significantly decreased (Fig. 3c-d). The activation of S1P synthesis in FSGS may serve as a compensatory mechanism in response to the loss of S1PR1 on GECs.

The endothelial protective effect of HDL in FSGS is dependent on the S1P/S1PR1 signaling axis

To investigate the impact of sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) on the regulation of endothelial function in GECs, we prepared rHDL with varying concentrations of S1P and cocultured them with HRGECs. Our results demonstrated that FSGS HDL, enriched with S1P, significantly upregulated the expression of p-enos and NO release in HRGECs (Fig. 4a-d and Supplementary Fig. S6a).

HDL’s endothelial protection in FSGS relies on S1P/S1PR1 signaling. (a,b) The reconstitution of S1P on HDL enhances the endothelial protective function of HDL in a dose-dependent manner. A Western blot analysis was conducted to assess the level of p-eNOS and a fluorescent probe was utilized to detect the NO levels in HRGECs cocultured with varying concentrations of S1P recombinant on rHDLs (equal to 30 µg/ml of HDL) for 6 h. (c,d) Using S1PR1-SiRNA to reduce the expression of S1PR1 in HRGECs, Western blot was performed to detect the expression level of p-eNOS, and a NO probe was utilized to measure the intracellular NO levels (scale bar: 100 μm). In panels (a-c), N-HDL was used as the basis for S1P enrichment to prepare rHDL. The indicated µM concentrations correspond to the final S1P levels in HDL after reconstitution. Data presented as mean ± SEM, N = 3, with significance levels marked as *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Statistical analysis employed one-way ANOVA. All experiments were replicated three times.

Furthermore, when S1P receptor 1 (S1PR1) was knocked down using siRNA (Designed and synthesized by Sangon Biotech, China), this protective effect of FSGS HDL was abolished (Fig. 4g-h and Supplementary Fig. S6b), indicating that the protective function of FSGS HDL on HRGECs is indeed dependent on S1P signaling.

The regulation of endothelial function by S1P is related to the activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway

S1P has been demonstrated to activate the PI3K/AKT pathway, resulting in an upregulation of p-eNOS expression14. To further investigate the relevance of this relationship in our studied diseases, HDL samples derived from NC, patients with MCD, and FSGS were employed for coculture HRGECs.Our experimental results showed a particularly prominent activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway in the FSGS group (Fig. 5a-c and Supplementary Fig. S7a).

S1P modulates endothelial function via PI3K/AKT pathway activation. (a-c) Western blot analysis of p-PI3K, p-AKT relative level in HRGECs cocultured with various groups of HDLs. (c-e) Western blot analysis of p-PI3K, p-AKT relative level in HRGECs cocultured with various concentrations of S1P recombinant on rHDLs for 6 h. (f-h) Using the specific inhibitor of PI3K, LY294002 (10.0 µmol/L), Western blot analysis was conducted to assess the relative levels of p-PI3K and p-AKT in HRGECs cocultured with F-HDL. Various groups of HDLs equal to 30 µg/ml. Data presented as mean ± SEM, N = 3, with significance levels marked as *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Statistical analysis employed one-way ANOVA. All experiments were replicated three time.

To further investigate the specific impacts of S1P, rrHDLs containing varying levels of S1P were prepared and cocultured with HRGECs. Notably, within exposure to rHDLs containing different concentrations of S1P, we observed a marked phosphorylation of PI3K and AKT, which progressively increased with the elevation of S1P concentration. Remarkably, this response remained consistent even after extended incubation periods, suggesting a durable activation of the associated To further elucidate the role of the PI3K/AKT pathway in mediating the effects of S1P, the specific inhibitor of PI3K, LY294002 (Abmole, USA), was utilized. When HRGECs were cocultured with LY294002, the stimulatory effects of rHDLs on HRGECs function were attenuated. This finding highlight the crucial role of PI3K/AKT activation in the regulation of HRGECs function by S1P (Fig. 5g-i and Supplementary Fig. S7c).

Discussion

In current scientific and medical context, electron microscopy is considered the gold standard for diagnosing glomerular nephropathies (GN), particularly in identifying the pathological characteristics of FSGS and MCD. However, challenges arising in the clarity of extracted tissue samples, which can be attributed to technical limitations or damage during processing, may hinder accurate diagnosis. Furthermore, insufficient sampling of glomeruli, typically requiring a minimum of 23 glomeruli, can lead to a missed diagnosis of FSGS, thereby posing a significant limitation in the diagnostic process15. While several studies have explored the potential value of specific biomarkers in differentiating FSGS from MCD, the current research landscape in this domain remains relatively nascent2.

Favourable HDL function plays a crucial role in safeguarding cardiovascular health and overall well-being by facilitating reverse cholesterol transport and exhibiting potent anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and anti-thrombotic properties. However, in individuals with nephropathy-associated proteinuria or chronic kidney disease (CKD), significant changes in the lipid profile alongside various facets of HDL metabolism, structure, and function can occur5. Recent studies on plasma lipidomics in CKD patients have revealed a significant association between increased proteinuria and specific changes in the lipid composition of HDL16. Our previous studies have investigated the role of HDL in diabetic nephropathy, revealing that HDL from diabetic patients with nephropathy demonstrates a more pronounced decline in its capacity to promote cell migration compared to HDL from diabetic individuals without nephropathy. This diminished function is attributed to elevated glycosylation levels in the affected HDL17. Currently, there is a lack of studies examining the compositional and functional changes of plasma HDL in other specific kidney diseases. Our study indicates that HDL in FSGS has the potential to enhance the expression of p-eNOS and NO release in GECs, in contrast to MCD and NC. This finding suggests that compensatory changes in HDL composition in FSGS may promote functional recovery in GECs.

In nephrotic syndrome, changes in HDL are not limited to alterations in ApoA-I levels. Studies have shown that other components of HDL, such as phospholipids, sphingolipids, and apolipoproteins, also undergo significant changes, which may impact HDL’sfunctionality in disease conditions5. These findings suggest that the structural and compositional integrity of HDL is critical for its protective roles, and further comprehensive investigations into the dynamic changes of HDL components in nephrotic syndrome are warranted. Phospholipids and sphingolipids constitute approximately 25 to 30% of the HDL components and play a pivotal role in determining the functionality of HDL. They modulate the surface charge and fluidity of HDL, facilitate binding to cellular receptors, and directly contribute to the anti-atherogenic properties of HDL18. Recent research has revealed significant correlations between elevated levels of albuminuria and increased relative concentrations of specific sphingolipids within HDL16. An impaired phospholipid or sphingolipid composition in HDL may contribute to HDL dysfunction in patients with diabetes19. Zheng and coworkers have isolated HDL phospholipid components from diabetic patients to investigate their effects on vascular endothelial cells11. By adopting a similar methodology, we separated HDL fractions from patients with FSGS, MCD, and healthy individuals. Our findings suggest the importance of lipid composition in the functional differences of HDL in FSGS and MCD, and implicating specific lipid components, such as phospholipids, as critical mediators of HDL’s influence on endothelial function in these renal diseases.

Previously, sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P), a sphingolipid, was primarily regarded as a structural element of biological membranes. However, over the past four decades, S1P has emerged as a crucial regulator of various cellular functions, encompassing cell growth, differentiation, proliferation, apoptosis, and inflammation20. The origins of S1P in blood have been recently identified. While hematopoietic cells, notably erythrocytes and platelets, serve as the primary sources of S1P in plasma, vascular endothelial cells are also involved in the synthesis and release of S1P16. Upon examining the HDL lipid fraction in FSGS, we observed a significant increase in S1P levels, compared to those in MCD cases and healthy individuals. These findings suggest that the activation of S1P during the progression of FSGS, potentially implicates the involvement of GECs in this process.

S1P is synthesized by sphingosine kinase 1 and 2 (SphK 1 and 2), after which it is exported into the extracellular space21. The degradation of S1P mainly occurs via two primary pathways: in addition to S1P lyase, which decomposes S1P into phosphoethanolamine and fatty aldehyde, S1P phosphatases 1 and 2 (SPP1 and SPP2) also contribute to its breakdown as members of the type 2 lipid phosphate phosphohydrolase family22. To elucidate the differential S1P synthesis in renal tissues of FSGS and MCD, we extracted total RNA from both groups and analyzed the expression of SPL, SPHK1/2, and SPP1/2 using RT-qPCR. Our findings revealed a significant upregulation of SPHK1/2 and downregulation of SPL and SPP1/2 in FSGS patients compared to MCD and NC groups. Endothelial S1PR1 mediates the vascular development, protection, and recovery of the kidney23. This research has confirmed that the impaired expression of S1PR1 in GECs of FSGS may stimulate the activation of S1P synthesis in the kidney.

Lee et al.12 demonstrated that sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) formed by model-rHDL particles selectively activates S1P receptor 1 (S1PR1) upon internalization. Notably, rHDL without S1P supplementation did not exhibit this effect, indicating that S1P transported within HDL selectively activates S1PR1. Following a similar approach, we constructed rHDL and discovered the underlying protective mechanism of FSGS HDL in GECs. This suggests that targeting the S1P/S1PR1 pathway may provide potential therapeutic strategies for treating FSGS and related kidney diseases. Modulating S1P signaling represents a promising approach to ameliorating endothelial dysfunction and promoting renal health in patients with these conditions.

Moreover, the enhanced stability of HDL-bound S1P compared to its albumin-bound form could significantly impact the distinct kinetics of receptor activation and signaling cascades. The hydrophobic tail of S1P inserts into the phospholipid monolayer of HDL, while its head group interacts with the aqueous phase. Through rotational mixing and low-temperature incubation, S1P is uniformly distributed on the HDL surface and stably bound12.Notably, HDL-bound S1P acts as a preferential agonist for the endothelial cell receptor S1P1, mitigating vascular inflammation. While S1P exerts pleiotropic effects by engaging multiple receptors, the stimulation of S1P1 by HDL-bound S1P, subsequently activating the PI3K-AKT pathway, emerges as a pivotal mechanism for rejuvenating endothelial cell function24. Our investigation provides new insights into the molecular pathways through which S1P exerts protective effects on renal endothelial cells, particularly in the context of FSGS. The observed attenuation of GECs function upon inhibition of the PI3K/AKT pathway suggests potential therapeutic targets for kidney diseases. Future studies are warranted to further explore the therapeutic implications of targeting this pathway in the management of kidney diseases.

This study has several limitations. First, the sample size was relatively small and derived from a single medical center, limiting the generalizability of our findings to larger and more diverse populations. Second, our lipidomic analysis primarily focused on the quantification and functional validation of S1P in HDL, while other lipid components such as LPC, SM, and sphingosine were not comprehensively analyzed. Preliminary non-targeted analyses showed no significant differences, which warrants further investigation with larger-scale targeted lipidomic studies. Third, our findings are based on in vitro models of HRGECs, which may not fully replicate the complex in vivo pathophysiological mechanisms of FSGS and MCD. Finally, while we demonstrated the short-term effects of S1P on endothelial function, the potential long-term impacts of S1P exposure or therapeutic modulation were not addressed in this study.

Conclusion

In summary, this study reveals significant disparities in HDL-linked S1P concentrations among individuals with FSGS versus MCD. These findings illuminate the underlying mechanisms of these nephrotic conditions and suggest potential avenues for diagnosis and treatment. Further exploration in this area may lead to innovative therapeutic interventions targeting FSGS and related glomerular disorders.

Data availability

All data are available in the main text or supplementary material.

Abbreviations

- S1P:

-

Sphingosine-1-phosphate

- HDL:

-

High density lipoprotein

- GECs:

-

Glomerular endothelial cells

- FSGS:

-

Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis

- MCD:

-

Minimal change disease

- p-eNOS:

-

Phosphorylated endothelial nitric oxide synthase

- NO:

-

Nitric oxide

- F-HDL:

-

FSGS highdensity lipoprotein

- M-HDL:

-

MCD highdensity lipoprotein

- N-HDL:

-

Normal highdensity lipoprotein

- rHDL:

-

Reconstituted HDL

- SPL:

-

Sphingosine-1-phosphate lyase

- SphK1/2:

-

Sphingosine kinases 1/2

- SPP1/2:

-

Sphingosine-1-phosphate phosphatases 1/2

References

Rovin, B. H. et al. KDIGO 2021 clinical practice guideline for the management of glomerular diseases. Kidney Int. 100 (4), S1–276 (2021).

Sohi, G. K. A review of glomerular diseases: focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) and minimal change disease (MCD). Sci. McMaster Undergrad. Sci. J. 1 (2), 9–17 (2019).

Sol, M. et al. Glomerular endothelial cells as instigators of glomerular sclerotic diseases. Front. Pharmacol. 11, 573557 (2020).

Tran-Dinh, A. et al. HDL and endothelial protection. Br. J. Pharmacol. 169 (3), 493–511 (2013).

Vaziri, N. D. HDL abnormalities in nephrotic syndrome and chronic kidney disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 12 (1), 37–47 (2016).

Karliner, J. S. Sphingosine kinase and sphingosine 1-phosphate in the heart: a decade of progress. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA Mol. Cell. Biol. Lipids 1831 (1), 203–212 (2013).

Lucke, S. & Levkau, B. Endothelial functions of sphingosine-1-phosphate. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 26 (1), 87–96 (2010).

Levkau, B. Sphingosine-1-phosphate in the regulation of vascular tone: a finely tuned integration system of S1P sources, receptors, and vascular responsiveness. Circ. Res. 103 (3), 231–233 (2008).

Chen, Q. et al. Proteomic analysis of idiopathic nephrotic syndrome triggered by primary podocytopathies in adults: regulatory mechanisms and diagnostic implications. J. Proteome Res. 23 (6), 2090–2099 (2024).

Chung, B. H., Wilkinson, T., Geer, J. C. & Segrest, J. P. Preparative and quantitative isolation of plasma lipoproteins: rapid, single discontinuous density gradient ultracentrifugation in a vertical rotor. J. Lipid Res. 21 (3), 284–291 (1980).

Tong, X. et al. The compensatory enrichment of sphingosine – 1- phosphate harbored on glycated high-density lipoprotein restores endothelial protective function in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 13 (1), 82 (2014).

Lee, M. H. et al. HDL3, but not HDL2, stimulates plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 release from adipocytes: the role of sphingosine-1-phosphate. J. Lipid Res. 51 (9), 2619–2628 (2010).

Hannun, Y. A. & Obeid, L. M. Principles of bioactive lipid signaling: lessons from sphingolipids. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 9 (2), 139–150 (2008).

Cartier, A. & Hla, T. Sphingosine 1-phosphate: lipid signaling in pathology and therapy. Science 366 (6463), eaar5551 (2019).

Smeets, B. et al. Detection of activated parietal epithelial cells on the glomerular tuft distinguishes early focal segmental glomerulosclerosis from minimal change disease. Am. J. Pathol. 184 (12), 3239–3248 (2014).

Lidgard, B. et al. High-density lipoprotein lipidomics in chronic kidney disease. Clin. Chem. 69 (3), 273–282 (2023).

Li, Y. et al. HDL in diabetic nephropathy has less effect in endothelial repairing than diabetes without complications. Lipids Health Dis. 15 (1), 76 (2016).

Camont, L. et al. Small, dense high-density lipoprotein-3 particles are enriched in negatively charged phospholipids: relevance to cellular cholesterol efflux, antioxidative, antithrombotic, anti-inflammatory, and antiapoptotic functionalities. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 33 (12), 2715–2723 (2013).

Denimal, D. et al. Significant abnormalities of the HDL phosphosphingolipidome in type 1 diabetes despite normal HDL cholesterol concentration. Atherosclerosis 241 (2), 752–760 (2015).

Carr, J. M., Mahalingam, S., Bonder, C. S. & Pitson, S. M. Sphingosine kinase 1 in viral infections. Rev. Med. Virol. 23 (2), 73–84 (2013).

Vickers, K. C. & Remaley, A. T. Lipid-based carriers of microRNAs and intercellular communication. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 23 (2), 91–97 (2012).

Gatfield, J. et al. Sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) displays sustained S1P1 receptor agonism and signaling through S1P lyase-dependent receptor recycling. Cell Signal. 26 (7), 1576–1588 (2014).

Perry, H. M. et al. Endothelial sphingosine 1–phosphate receptor–1 mediates protection and recovery from acute kidney injury. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 27 (11), 3383–3393 (2016).

Galvani, S. et al. HDL-bound sphingosine 1-phosphate acts as a biased agonist for the endothelial cell receptor S1P 1 to limit vascular inflammation. Sci. Signal. 8(389) (2015).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the patients who participated. We also thank Doctor Lin Mei from the First Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University for her assistance with our experimental technology.

Funding

This research was supported by Joint Funds for the innovation of Science and Technology, Fujian province (2020Y9074 to Lixin Wei), by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82070727 to Lixin Wei), and by Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province (2020J011024 to Lixin Wei).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LXW QLC Conceived and designed the experiments.RYG JMX ZXY CRY collected the samples. YFX QPY LFL SHC carried out the experiments. WJL YGL performed the statistical analysis. YFX wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

The study was conducted in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval from the Ethics Committee of Fujian Medical University Union Hospital (Fujian, China, 2023QH020). Prior to participation, informed consent was obtained to ensure voluntary agreement and full understanding.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xiong, Y., Ye, Q., Liu, L. et al. The compensatory enrichment of sphingosine-1-phosphate on HDL in FSGS enhances the protective function of glomerular endothelial cells compared to MCD. Sci Rep 15, 1530 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85865-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85865-8