Abstract

This study investigates the critical impact of incipient sediment motion on sediment transport estimation and riverbed evolution prediction. In this research, we examine the effects of ice cover on the vertical distribution of flow velocity, establishing a mathematical relationship between the vertical average flow velocities in open channel and ice-covered flows. This leads to the derivation of a formula for incipient motion velocity under ice cover. Additionally, the study analyzes the riverbed evolution process under ice jam conditions. The proposed formula is applicable to both open channel and ice-covered flows, effectively capturing the characteristics of incipient sediment motion for non-cohesive and cohesive sediments. The calculated incipient motion velocities closely align with the empirical data from existing literature. The study reveals that the roughness of ice cover significantly influences the incipient motion velocity of sediment, with higher ratios of ice cover roughness to riverbed roughness promoting sediment initiation under more favorable hydraulic conditions. Furthermore, the riverbed beneath ice jams experiences significant scouring. Field observations indicate that when ice jams form in localized sections of the river, the displacement of the main flow can substantially increase flow velocity in areas away from the ice jam, leading to scouring in non-ice-jammed areas and sedimentation in ice-jammed areas. The uneven distribution of ice jam is likely a critical factor contributing to discrepancies between theoretical predictions and observed outcomes. The complexity and limited data associated with the initiation of cohesive sediments pose challenges in validating the proposed formula for these sediment types.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the higher latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere, over 60% of river systems experience seasonal ice cover during the winter months1. The presence of ice significantly alters the flow dynamics, which in turn modifies the processes of sediment transport and riverbed morphodynamics2,3,4,5. Despite the substantial influence of river ice on sediment transport and channel evolution during winter, this impact is often underappreciated. This oversight stems from the typically diminished discharge rates during the freezing period, coupled with the reduced flow velocity and diminished bed shear stress beneath ice cover, which collectively result in a significant decrease in sediment transport rates. Experimental data derived from flume studies reveal that, under ice cover, the transport rates of both suspended sediment and bedload can be reduced by up to 95% relative to comparable conditions in open channels6,7,8,9. Consequently, research has predominantly focused on the breakup period, during which the movement of river ice exerts the most dramatic effects on sediment transport and channel changes10,11. Nonetheless, even during periods of low discharge, specific ice regimes, such as ice jams, can still induce high rates of sediment transport12. Additionally, phenomena such as anchor ice formation and its subsequent release can mobilize substantial amounts of sediment, including larger particles such as cobbles that may remain stationary under open channel flow conditions13,14,15. The incipient sediment motion under these ice regimes can result in substantial scouring of the riverbed and bridge piers, with significant implications for both aquatic ecosystems and the structural integrity of hydraulic infrastructure. These effects are particularly pronounced in areas affected by ice jams16,17,18. Therefore, it is crucial to quantitatively evaluate the onset of sediment motion under ice cover to enhance predictions of riverbed evolution during the freezing period.

The processes governing sediment transport under ice cover and their impacts on riverbed erosion and deposition remain poorly understood, primarily due to the challenges posed by harsh winter conditions, limitations in monitoring technologies, and gaps in theoretical frameworks. Existing research has predominantly focused on the dynamics of suspended sediment transport beneath ice cover. It is generally accepted that sediment concentrations are significantly lower during the freezing period compared to ice-free conditions. Conversely, during the breakup period, suspended sediment concentrations can increase markedly, potentially exceeding levels observed during peak flood events10,12,19,20. Therefore, during the stable freeze-up period, riverbed evolution is predominantly driven by bedload transport. Two fundamental methods for quantifying incipient sediment motion are critical shear stress and critical velocity, both analyzed through the lens of sediment stability mechanics. Critical velocity is often preferred in field applications due to its practicality and ease of measurement, as it is based on the vertical average flow velocity21,22.

While extensive research has been conducted on the incipient motion velocity of sediment in open channel flow, covering a range of sediment types and conditions—including uniform and non-uniform sediments, cohesive and non-cohesive sediments, and the influence of vegetation23,24,25,26. Similar advances have not been made in understanding incipient sediment motion under ice cover. The complexity of incipient sediment motion processes necessitates laboratory-based experiments to determine the hydraulic conditions required for sediment transport. Through model testing27, derived a formula for incipient motion velocity of sediment under ice cover using dimensional analysis, concluding that the presence of ice lowers the location of the maximum flow velocity, thereby making incipient sediment motion more likely. Mathematical models that simulate bedload and suspended sediment transport, as well as riverbed deformation under the influence of river ice, underscore the importance of accounting for ice effects in studies of sediment transport and riverbed morphological changes in alluvial rivers28,29. Under specific ice regimes, such as ice jams, the formation and release of the jam can induce significant scouring of the riverbed, indicating that ice jam facilitate the incipient sediment motion17,30,31,32,33,34. While these studies have enhanced our understanding of sediment transport and riverbed evolution under ice cover, they have not provided a comprehensive quantitative expression for incipient motion velocity of sediment under ice cover, nor have they fully elucidated the dynamic mechanisms by which incipient sediment motion during freezing period influences riverbed evolution.

From a mechanical perspective, analyzing the forces acting on sediment particles to derive conditions for incipient sediment motion is a widely employed approach in sediment transport studies35. Whether in open channel or ice-covered flows, the distribution of forces acting on bedload sediment remains fundamentally unchanged. Thus, as long as the flow velocity reaches the critical threshold, incipient sediment motion will occur. For identical sediment particles, the critical velocity required for initiation remains consistent, with the presence of ice primarily altering the vertical distribution of flow velocity, thereby affecting the vertical average velocity and the velocity directly influencing bedload sediment36,37. In quantifying the threshold for incipient motion velocity, the near-bed flow velocity acting on the sediment is challenging in practical applications. Substituting vertical average flow velocity is advantageous as it enhances experimental operability and facilitates data acquisition. Building on this logical framework, we conduct a force analysis of bedload sediment and establish a mathematical relationship between flow velocities in open channel and ice-covered flows. This relationship is used to derive a formula for incipient motion velocity of sediment under ice cover, which is subsequently validated using experimental data from existing literature. Additionally, the study provides an explanation for the riverbed evolution process in ice-jammed area, aiming to reveal the dynamic mechanisms through which sediment transport during the freezing period influences riverbed evolution.

Theory

Forces and incipient motion velocity of sediment

Under ice-free and ice-covered conditions, the vertical distribution of flow velocity exhibits distinct patterns, which significantly influence the incipient motion of sediment. Assuming a uniform sediment distribution on the riverbed and a rolling initiation mechanism, a force analysis of the bedload sediment particles can be conducted, as illustrated in Fig. 1.

The forces driving incipient sediment motion include the drag force of flow \(({F_D})\) and the lift force \(({F_L})\), while the force resisting incipient sediment motion is the gravitational force of the sediment \((W)\). The corresponding expressions are as follows22:

where \({C_D}\) and \({C_L}\) are the coefficients of drag force and lifting, respectively; \(d\) is the sediment size; \(\gamma\) and \({\gamma _s}\) are the specific weight of water and sediment, respectively; \({a_1}\) and \({a_2}\) are the area coefficients of the sediment in the flow direction and the vertical direction, respectively; \({a_3}\) is the volume fraction coefficient of the sediment, when the sediment particles are approximated as spheres, \({a_3}={\pi \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {\pi 6}} \right. \kern-0pt} 6}\); \(g\) is the gravitational acceleration; and \(U\) is the vertical flow velocity at any water depth in open channel flow, when the velocity acts on sediment particles, it represents the instantaneous flow velocity acting on the sediment.

When dealing with cohesive sediments, it is essential to consider the cohesive force \((N)\) between sediment particles, which is one of the primary forces resisting incipient sediment motion. Due to the complexity of the origins and mechanisms of cohesive forces, there is no consensus on a single approach to quantifying these forces, leading to the development of various theoretical formulations35. Here, we refer to the approach of22, which posits that the cohesive force is related to the thickness of the voids between sediment particles, the horizontal projection area of the particles, and the vertical pressure exerted on the particles. The expression for the cohesive force is given as follows:

where \({a_4}\) is a coefficient, \({d_1}\) is a reference particle diameter selected for comparison with the sediment particle diameter, \(H\) is the water depth in open channel flow, \({H_a}\) is the height of the water column corresponding to atmospheric pressure, and \(s\) is an exponent.

Considering that after the formation of ice cover, the atmosphere no longer directly contacts the water surface, making it challenging to directly determine the vertical pressure on the sediment particles, the vertical pressure is still calculated based on a water column height of 10 m, similar to the conditions in open channel, i.e., \({H_a}=10 \; {\text{m}}\).

Based on the above results, the moment equilibrium equation for the critical conditions of incipient sediment motion can be established as follows:

where \({K_1}d\), \({K_2}d\), \({K_3}d\) and \({K_4}d\) represent the force arms of the forces \({F_D}\), \({F_L}\), \(W\) and \(N\), respectively.

Substituting Eqs. (1)–(4) into Eq. (5) and simplifying, we can obtain:

where the subscript c denotes the critical initiation condition.

The vertical distribution of flow velocity in open channel flow is expressed as follows:

where \({U_m}\) is the vertical maximum flow velocity in open channel flow, \(y\) is the height form the riverbed, \(m\) is the exponent of velocity distribution.

According to the principle of equal areas, we derive the following:

where \(\overline {U}\) is the vertical average flow velocity in open channel flow.

Then, it can be obtained that:

By substituting Eq. (9) into Eq. (7), the vertical flow velocity distribution in open channel flow can be expressed as follows:

Substituting the vertical average flow velocity for the incipient motion velocity of sediment, and assuming an exponential distribution for the flow velocity profile, as indicated in Eq. (10), and taking the characteristic height \(y=ad\), and then integrating into Eq. (6):

where \({C_1}=\frac{1}{{\left( {1+m} \right){a^m}}}\sqrt {\frac{{2{K_3}{a_3}}}{{{K_1}{C_D}{a_1}+{K_2}{C_L}{a_2}}}}\), \({C_2}=\frac{{{K_4}{a_4}}}{{{K_3}{a_3}}}\), \(m\)is the velocity distribution exponent in open channel flow.

Calibrated using the empirical data from previous study22, \({C_1}=1.34\), \({C_2}=0.00000496\), \(s=0.72,\) \(m=1/7\), with sediment density taken as \({\rho _s}=2650{\text{kg/}}{{\text{m}}^{{3}}}\), water density as \(\rho =1000 \; {\text{kg/}}{{\text{m}}^{{3}}}\), and the gravitational acceleration \(g=9.8 \; {\text{m/}}{{\text{s}}^{{2}}}\), the parameter values are substituted into Eq. (11) and simplified. Consequently, the formula for incipient motion velocity of sediment is derived as follows:

The relationship between the vertical average velocities in open channel and ice-covered flows

According to Einstein’s hypothesis, the entire flow cross-section is partitioned into an upper ice zone and a lower bed zone, with the plane of maximum velocity demarcating the boundary between these two zones38. The vertical flow velocity distribution is assumed to satisfy three key conditions: (1) the velocity distribution within both the ice zone and the bed zone adheres to an exponential profile; (2) the vertical average flow velocities in the ice zone and the bed zone are equivalent, \(\overline {{{u_i}}} =\overline {{{u_b}}}\); and (3) the energy slope in both the ice zone and the bed zone is also equal, \({J_i}={J_b}\)38. The vertical flow velocity distribution under ice cover is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Based on the partitioning results (where subscripts i and b represent the parameters corresponding to the ice zone and the bed zone, respectively), the vertical flow velocity in both zones adheres to an exponential distribution. Therefore, the vertical distribution of flow velocity in the ice zone and the bed zone is expressed as follows:

where \({u_m}\) is the vertical maximum flow velocity in ice-covered flow, \({h_b}\) is the water depth in bed zone.

According to the principle of equal areas, similarly, the vertical flow velocity distributions for both the ice zone and the bed zone can be obtained:

Assuming that the sediment begins to move when the near-bed flow velocity reaches a certain threshold, the flow velocities in ice-covered and open channel flows are considered equal. Equating Eq. (16) to Eq. (10):

where \({u_c}=\overline {{{u_b}}}\), \({U_c}=\overline {U}\), \({u_c}\) and \({U_c}\) represent the critical vertical average velocities for incipient sediment motion in ice-covered and open channel flows, respectively, both equivalent to the incipient motion velocity; \({y_c}\) is the critical height at which the flow acts on the sediment, typically taken as \({{2d} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{2d} 3}} \right. \kern-0pt} 3}\)35; the value of \({m}\) for open channel flow is given as 1/722, for ice-covered flow, exponents with two-power law distributions have been partially studied39,40, but for exponential distributions, due to the scarcity of relevant studies, the value of \({m_b}\) has not been clearly established. For simplicity, it is assumed that \(m={m_b}\). Therefore, we have:

This establishes the mathematical relationship between the incipient motion velocity in ice-covered and open channel flows. The value of \({h_b}\) or the location of the point of vertical maximum flow velocity is affected by the ice cover roughness.

According to the Manning formula:

where \({R_i}\) and \({R_b}\) are the hydraulic radius of the ice zone and the bed zone, respectively; \({n_i}\) and \({n_b}\) are the roughness coefficients of the ice cover and the riverbed, respectively.

According to the previous assumption, equating Eqs. (19) to (20):

For wide and shallow rivers, the hydraulic radius can be considered equal to the water depth, thus \({R_i}=h - {h_b},\) \({R_b}={h_b},\) leading to the following relationship:

Substituting Eq. (22) into Eq. (18), the relationship between the incipient motion velocity in ice-covered and open channel flows is obtained as follows:

By combining Eqs. (8) and (23), \(h \approx H\), the formula for incipient motion velocity in ice-covered flow can be obtained:

when the ice cover roughness (\({n_i}\)) is zero, the formula reduces to the incipient motion velocity for open channel flow.

In this study, the calculation of \({n_i}\) and \({n_b}\) can be performed according to the following steps.

The comprehensive roughness \({n_c}\) is first calculated using the one-dimensional difference equation for steady flow27:

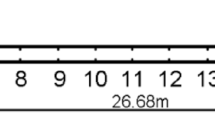

where \(\Delta Z\) and \(\Delta x\) represent the water level difference and distance between upstream and downstream, respectively; \(A\) is the flow cross-sectional area; \(Q\) is the discharge; \(\overline {B}\) is the average width; \(\overline {h}\) is the average water depth.

Then, \({n_b}\) can be obtained based on the values determined for comparable open water conditions. According to the Manning formula and the Darcy-Weisbach formula, we can obtain:

where \({R}\) and \({J}\) represent the hydraulic radius energy slope in open channel flow, respectively.

Finally, according to Belokon-Sabeneev’s comprehensive roughness formula, \({n_i}\) can be calculated41:

According to Eq. (24), the larger the ratio of ice cover roughness to riverbed roughness (\({{{n_i}} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{{n_i}} {{n_b}}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {{n_b}}}\)), the smaller the incipient motion velocity (\({u_c}\)). This observation is consistent with practical conditions: as the location of maximum vertical flow velocity shifts toward the smoother side, an increase in ice cover roughness moves the location of maximum vertical flow velocity closer to the riverbed, thereby increasing the near-bed velocity and facilitating incipient sediment motion. This finding is aligns with the study by previous study27. Ice jams, characterized by high roughness, causes the location of maximum vertical flow velocity to shift toward the riverbed.

Equation (24) further indicates that under the same conditions, the incipient motion velocity of sediment in open channel flow is greater than that in ice-covered flow, and as the roughness of the ice cover increases, the incipient motion velocity gradually decreases. Therefore, in ice-covered flow, the larger the ice cover roughness, the lower the incipient motion velocity. This implies that in areas affected by ice jams, the hydraulic conditions necessary for incipient sediment motion are more easily satisfied, rendering the riverbed more susceptible to scouring and deformation.

Validation of the Formula

The formula was validated using the experimental data from previous study27. The experiments were conducted in a recirculating flume with dimensions of 18.0 m in length, 0.50 m in width, and 0.60 m in depth, featuring glass walls and a concrete bottom. The sheet ice cover was simulated using a floating foam panel, the foam panels were modified by adding small wood pieces to create rough underside surfaces. The experiments were conducted under prismatic, steady, and uniform flow conditions. Three types of non-cohesive sediment with median grain sizes of 0.32 mm, 0.85 mm, and 1.32 mm were used. The ice cover roughness \({n_i}\) values were 0.0212 and 0.0347, and the riverbed roughness \({n_b}\) values were 0.0109, 0.0128, and 0.0139. The estimation of \({n_i}\) and \({n_b}\) is determined according to the steps outlined in Eqs. (25) to (27).

There were six Runs in total, each corresponding to a different roughness ratios between the ice cover and the riverbed. The main data in this experiment are summarized in Table 1.

Using Eq. (24), the incipient motion velocity of sediment under ice cover was calculated for each Run. The calculated values of incipient motion velocity were then compared with the measured values, as shown in Fig. 2. Except for the Case4, where the calculated incipient motion velocity was slightly overestimate, the remaining calculated values generally align with the measured values along the 45° line. Overall, the calculated incipient motion velocities under ice cover agree well with the experimental results, validating the effectiveness of the proposed formula.

To quantify the accuracy of the predicted incipient motion velocity of sediment under ice cover as determined by the proposed model, error statistics for the six Runs are carried out and shown in Table 2.

The mean absolute error (MAE) is defined as the average value of the difference between the calculated and measured incipient motion velocity under ice cover:

where \({n}\) is the sampling number of the measured incipient motion velocity for each Run.

The mean relative error (MRE) is expressed as:

Table 2. Error statistics of the incipient motion velocity of sediment for all Runs.

Based on the calculation results, the average MAE for all Runs of the incipient motion velocity of sediment is 5.60%, and the average MRE is 0.013 m/s, indicating that the formula proposed in this study demonstrates a high level of accuracy.

Discussion

The impact of the roughness ratio n i n b and water depth hon the incipient motion velocity of sediment

According to Eq. (24), the relationship between the incipient motion velocity and sediment size was calculated, and the results are shown in Fig. 3. Regardless of the roughness ratio (\({{{n_i}} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{{n_i}} {{n_b}}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {{n_b}}}\)), the incipient motion velocity curve exhibits a pattern of first decreasing and then increasing as the sediment size increases. This indicates that there is a minimum incipient motion velocity corresponding to the most easily initiated sediment size. When \(h=0.15 \, {\text{m}}\), the most easily initiated sediment size (\({d_c}\)) is approximately 0.16 mm, when \(h=3 \; {\text{m}}\), \({d_c}\) increases to about 0.20 mm. This indicates that as the water depth increases, the critical initiation size also increases. When \(d<{d_c}\), cohesive forces dominate, and the smaller the sediment size, the higher the incipient motion velocity. Conversely, when \(d>{d_c}\), gravity dominates, and the larger the sediment size, the higher the incipient motion velocity, which is consistent with the principles of incipient sediment motion22,35.

Taking \({{{n_i}} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{{n_i}} {{n_b}}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {{n_b}}}=1\) as an example, when the water depth \(h=0.15 \; {\text{m}}\) and the sediment size \(d=0.16 \; {\text{mm}},\) the incipient motion velocity \({u_c}\) is 21.11 cm/s. When the water depth increases to \(h=3 \; {\text{m}}\), \({u_c}\) increases to 37.43 cm/s. This means that as the water depth increases 20 times, the incipient motion velocity increases by approximately 1.8 times, indicating that under the same ice cover and riverbed conditions, the incipient motion velocity rises with increasing water depth. Similarly, when the water depth and sediment size remain constant, the incipient motion velocity also varies with changes in the roughness ratio. For a water depth of \(h=0.15 \; {\text{m}}\) and a sediment size of \(d=0.16 \; {\text{mm}}\), when \({{{n_i}} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{{n_i}} {{n_b}}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {{n_b}}}=1\) increases to \({{{n_i}} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{{n_i}} {{n_b}}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {{n_b}}}=2\) and \({{{n_i}} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{{n_i}} {{n_b}}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {{n_b}}}=3\), the incipient motion velocity \({u_c}\) decreases from 21.11 cm/s to 19.28 cm/s and 18.02 cm/s, respectively, representing decreases of 8.67% and 14.64%. This indicates that greater ice cover roughness results in a lower incipient motion velocity

The formula derived in this study is based on the incipient motion velocity formula by previous study22. The parameters of that formula were calibrated under shallow water depth conditions (\(h=0.15 \; {\text{m}}\)). Given that the water depth in natural rivers is significantly greater than that in model flumes, applying these parameters to assess incipient sediment motion in rivers may impact practical applications. However, the physical principles embodied in the formula remain valid; the greater the ice cover roughness, the more easily sediment is initiated, consistent with the findings of previous study27. Additionally, the formula indicates that even during the stable freeze-up period with very low flow rates, significant bed sediment transport may still occur under specific ice regime (e.g., ice jams), as noted by previous study12. The rougher the morphology of the ice cover bottom, the more pronounced the bed deformation, which is of great significance for predicting riverbed evolution in ice-covered rivers.

Riverbed erosion in ice-jammed river

When \({n_i}\) is large, such as in the case of an ice jam, the hydraulic conditions for incipient sediment motion become more favorable, leading to significant riverbed erosion. Observational data from the Inner Mongolia section of the Yellow River indicate a strong correlation between the presence of ice jam and riverbed evolution. Figure 4 shows the observed ice jam and riverbed topography at the Toudaoguai Hydrological Station cross-section during the winter of 2013–2014. On January 1, 2014 (Fig. 4(a)), after a stable ice cover had formed, a localized ice jam with a maximum thickness of approximately 2.2 m developed on the right side of the main channel. The cross-sectional area of the ice jam accounted for about 3/7 of the flow area. The cross-sectional shape of the main channel was roughly symmetrical on both sides, with the main flow of the river centered (from station distance 500 m to 580 m). The maximum water depth was approximately 4.1 m, with the water depth beneath the ice jam ranged from 0.3 m to 3.4 m.

From January 18 (Fig. 4(b)) to February 3 (Fig. 4(c)), the ice cover thickened, and the position of the ice jam remained unchanged, but the cross-sectional area of the ice jam decreased, and the ice jam on the right side disappeared. The main flow shifted to the left side, causing intense erosion on the left riverbed, with the maximum erosion depth reaching 3.1 m at station distance 440 m. By February 22 (Fig. 4(d)), the ice cover had continued to thicken, and the ice jam further shrank and deformed. The main flow remained on the left side, causing significant downcutting in the channel between stations distance 380 m and 520 m, with an erosion depth of 1.1 m at station distance 460 m. The original main channel (form station distance 540 m to 580 m) experienced sediment deposition, with a maximum deposition thickness of 0.8 m. The area where the riverbed elevation increased was also the main area where the ice jam accumulated. Erosion occurred in the right channel of the ice jam, with an erosion depth of 1.3 m at station distance 720 m.

During the breakup period, on March 11 (Fig. 4(e)), as the temperature rose, the ice cover in the left channel melted significantly, and the ice jam on both sides shrank simultaneously. During this phase, the main flow of the river remained on the left side, with the maximum water depth still located at station distance 440 m, remaining largely unchanged. The riverbed began to accumulate sediment overall, with a maximum elevation increase of about 0.5 m on the left side and about 0.3 m of sediment deposition under the ice jam. By March 19 (Fig. 4(f)), the ice cover on the left side completely melted, the ice jam continued to shrink, and the main flow remained on the left side of the channel, although it showed a tendency to shift to the right. Some ice cover and an ice jam about 1 m thick persisted on the right side of the channel. The riverbed saw significant sediment deposition, with the maximum thickness of 1.6 m occurring beneath the ice jam.

The observed data at the Toudaoguai hydrological station cross-section reveals that after the river freezes, irregularly shaped ice jams form under the ice cover. These ice jams gradually diminish over time, ultimately disappear as the river thaws. The presence of ice jams forces the main flow towards areas free of them, resulting in significant erosion and deposition adjustments within the cross-section. Slight deposition occurs beneath the ice jams, while the main flow progressively shifts away from these areas, leading to erosion in the regions without ice jam. As the ice jams gradually shrinks, the riverbed begins to silt up again, albeit at a slower rate. This process is driven by the ice jams’ alteration of flow velocity distribution, which affects the incipient sediment motion. The resulting bed deformation further redistributes flow velocity, influencing the erosion of the ice jams. As the ice jams shrinks, there influence gradually weakens. The changes in riverbed topography within the ice jam cross-section indirectly illustrate the pattern of increased ice jam leading to riverbed erosion; decreased ice jam leading to riverbed deposition.

In the river cross-section where the ice jam is present, the riverbed generally exhibits erosion, aligning with existing research findings34. However, due to the uneven distribution of ice jams in natural rivers, the high roughness generates substantial resistance, causing the main flow to shift. In areas without ice jams, the vertical average flow velocity increases significantly, surpassing the threshold velocity required to incipient sediment motion, thereby leading to erosion in these non-ice-jam areas. This phenomenon deviates slightly from the conclusions derived from theoretical Eq. (24). If the entire river cross-section were covered by an ice jam, meaning the cross-section was completely occupied by the ice jam, the roughness of the ice jam would directly influence incipient sediment motion, reducing the required velocity and energy for sediment mobilization, and resulting in overall riverbed erosion. This reflects the dynamic mechanism through which incipient sediment motion under ice cover influences the evolution of riverbed.

Limitations of the formula

In deriving the formula of incipient motion velocity in this study, certain assumptions were made regarding the flow velocity in both the ice-covered region and riverbed region. These assumptions are idealized and may not fully represent actual conditions. The derived formula takes into account the effect of cohesive forces and assumes that the sediment initiate movement primarily through rolling. However, the experiments used to validate involved non-cohesive sediment, and there is currently a lack of experimental data on the incipient motion velocity of cohesive sediment under ice cover. Therefore, the applicability of the formula to the initiation of cohesive sediment requires further consideration and verification in the future.

Additionally, the cohesive forces can significantly alter the mode of incipient sediment motion. While non-cohesive sediment typically initiates movement through rolling or sliding as granular materials, cohesive sediment may begin to move in a sheet or clump form under the influence of flow erosion42. Currently, most studies still treat the initiation of sediment under cohesive forces as the initiation of individual particles, which often leads results that often deviate considerably from actual conditions. Meanwhile, the proposed formula in this paper is specifically designed for prismatic, steady, and uniform flow conditions. It has not yet been validated using sediment incipient velocity data from natural river channels. Therefore, its applicability remains limited to prismatic, steady, and uniform flow conditions as well as physical model experiments. Future research should further investigate the impact of changes in the mode of initiation on the movement of cohesive sediment, strengthen the observation and validation of sediment incipient velocity under ice in natural river channels, and enhance our understanding and ability to predict these dynamics.

Conclusions

Quantitatively expressing incipient sediment motion under ice cover holds great importance for predicting riverbed evolution during winter. This study established a mathematical relationship between the vertical average flow velocities for open channel and ice-covered flows, derived a formula for incipient motion velocity of sediment under ice cover, and validated it with measured data. The formula is structurally simple, requires few physical parameters, and the calculated results align well with the measured data, demonstrating its effectiveness.

The findings highlight the significant impact of ice cover roughness on incipient motion velocity, suggesting that the hydraulic conditions for incipient sediment motion under ice cover become more favorable, particularly during special ice regime such as ice jams, where sediment is more prone to initiate and lead to riverbed erosion. The theoretical formula was further tested against observed riverbed evolution under ice jam conditions, revealing that in natural rivers, ice jam tend to accumulate or distribute within localized areas of the channel. The ice jam considerably increases flow resistance, causing the main flow to shift away from the ice jam, leading to erosion in non-ice-jam areas, while slight deposition occurs in the ice jam area. The difference from the theoretical formula is attributed to the uneven distribution of ice jams in natural rivers.

In conclusion, the riverbed cross-section affected by ice jams experiences increased roughness and altered flow velocity, making incipient sediment motion and subsequent riverbed erosion more likely. Due to the lack of experimental data on the incipient motion velocity of cohesive sediment, this study did not validate such cases. Moreover, cohesive sediment affects the initiation mode, and the influencing factors for cohesive sediment are more complex than for non-cohesive sediment, necessitating further consideration in future research.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Abbreviations

- \(F_{D}\) :

-

The drag force of flow

- \(F_{L}\) :

-

The lift force of flow

- \(W\) :

-

The gravitational force of the sediment

- \(N\) :

-

The cohesive force

- \(C_{D}\) :

-

The coefficients of drag force

- \(C_{L}\) :

-

The coefficients of lifting

- \(d\) :

-

Sediment size, it typically represents the median grain size

- \(d_{1}\) :

-

A reference particle diameter selected for comparison with the sediment particle diameter

- \(\rho\) :

-

The sediment density

- \(\rho_{s}\) :

-

The sediment density

- \(\gamma\) :

-

The specific weight of water

- \(\gamma_{s}\) :

-

The specific weight of sediment

- \(a_{1}\) :

-

The area coefficients of the sediment in the flow direction

- \(a_{2}\) :

-

The area coefficients of the sediment in the vertical direction

- \(a_{3}\) :

-

The volume fraction coefficient of the sediment

- \(a_{4}\) :

-

A coefficient

- \(g\) :

-

The gravitational acceleration

- \(h\) :

-

The water depth in ice covered channel

- \(H\) :

-

The water depth in open channel

- \(H_{a}\) :

-

The height of the water column corresponding to atmospheric pressure

- \(s\) :

-

An exponent

- \(K_{1} d\) :

-

The force arms of the forces \(F_{D}\)

- \(K_{2} d\) :

-

The force arms of the forces \(F_{L}\)

- \(K_{3} d\) :

-

The force arms of the forces \(W\)

- \(K_{4} d\) :

-

The force arms of the forces \(N\)

- \(y\) :

-

Characteristic height

- \(y_{c}\) :

-

The critical height at which the flow acts on the sediment

- \(u_{c}\) :

-

The incipient sediment motion in ice-covered flow

- \(u_{c,meseared}\) :

-

The measured incipient motion velocity in ice-covered flow

- \(u_{c,calculated}\) :

-

The calculated incipient motion velocity in ice-covered flow

- \(U_{c}\) :

-

The incipient sediment motion in open channel flow

- \(u_{m}\) :

-

The max vertical velocity in ice-covered flow

- \(h_{b}\) :

-

The height from the riverbed in bed zone

- \(U\) :

-

The vertical flow velocity at any water depth in open channel flow

- \(u_{i}\) :

-

The vertical flow velocity at any water depth in ice zone

- \(u_{b}\) :

-

The vertical flow velocity at any water depth in bed zone

- \(\overline{U}\) :

-

The vertical average flow velocity in open channel

- \(\overline{{u_{i} }}\) :

-

The vertical average flow velocity in ice zone

- \(\overline{{u_{b} }}\) :

-

The vertical average flow velocity in bed zone

- \(m\) :

-

The velocity distribution exponent in open channel flow

- \(m_{i}\) :

-

The velocity distribution exponent of the ice zone

- \(m_{b}\) :

-

The velocity distribution exponent of the bed zone

- \(R\) :

-

The hydraulic radius in open channel flow

- \(R_{i}\) :

-

The hydraulic radius of the ice zone

- \(R_{b}\) :

-

The hydraulic radius of the bed zone

- \(J\) :

-

The energy slope in open channel flow

- \(J_{i}\) :

-

The energy slope of the ice zone

- \(J_{b}\) :

-

The energy slope of the bed zone

- \(n_{i}\) :

-

The ice cover roughness

- \(n_{b}\) :

-

The riverbed roughness

- \(n_{c}\) :

-

The comprehensive roughness

- \(\Delta Z\) :

-

The water level difference between upstream and downstream

- \(\Delta x\) :

-

The distance between upstream and downstream

- \(A\) :

-

The flow cross-sectional area

- \(Q\) :

-

The discharge

- \(\overline{B}\) :

-

The average width in ice covered flow

- \(\overline{h}\) :

-

The average water depth in ice covered flow

References

Rokaya, P., Budhathoki, S. & Lindenschmidt, K. E. Trends in the timing and magnitude of ice-jam floods in Canada. Sci. Rep. 8, 5834 (2018).

Kämäri, M. et al. River ice cover influence on sediment transportation at present and under projected hydroclimatic conditions: RIVER ICE COVER INFLUENCE ON SEDIMENT. Hydrol. Process. 29, 4738–4755 (2015).

Krishnappan, B. G. Suspended Sediment Profile for Ice-covered flows. J. Hydrol. Eng. 109, 385–399 (1983).

Lotsari, E., Lintunen, K., Kasvi, E., Alho, P. & Blåfield, L. The impacts of near-bed flow characteristics on river bed sediment transport under ice-covered conditions in 2016–2021. J. Hydrol. 615, 128610 (2022).

Tsai, W. F. & Ettema, R. Ice cover influence on transverse bed slopes in a curved alluvial channel. J. Hydraul Res. 32, 561–581 (1994).

Ettema, R., Braileanu, F. & Muste, M. Laboratory Study of Suspended-Sediment Transport in Ice-Covered Flow. (1999).

Sayre, W. W. & Song, G. B. Effects of Ice Cover on Alluvial Channel Flow and Sediment Transport Process. (1979).

Smith, B. T. & Ettema, R. Ice-Cover Influence on Flow and Bedload Transport in Dune-Bed Channels. (1995).

Wuebben, J. L. A Laboratory Study of flow in an ice-covered sand bed Channel (The University of Iowa, 1986).

Beltaos, S. Extreme sediment pulses during ice breakup, Saint John River, Canada. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 128, 38–46 (2016).

Beltaos, S. & Burrell, B. C. Effects of river-ice breakup on sediment transport and implications to Stream environments: A review. Water 13, 2541 (2021).

Turcotte, B., Morse, B., Bergeron, N. E. & Roy, A. G. Sediment transport in ice-affected rivers. J. Hydrol. 409, 561–577 (2011).

Kempema, E. W. & Ettema, R. Anchor ice rafting: Observations from the laramie river. River Res. Appl. 27, 1126–1135 (2011).

Kerr, D. J., Shen, H. T. & Daly, S. F. Evolution and hydraulic resistance of anchor ice on gravel bed. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 35, 101–114 (2002).

Martin, S. Frazil Ice in Rivers and oceans. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 13, 379–397 (1981).

Li, G., Sui, J., Sediqi, S. & Dziedzic, M. Local scour around submerged angled spur dikes under ice cover. Int. J. Sediment. Res. 38, 781–793 (2023).

Manolidis, M. & Katopodes, N. Bed Scouring during the release of an ice Jam. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2, 370–385 (2014).

Namaee, M. & Sui, J. Local scour around two side-by-side cylindrical bridge piers under ice-covered conditions. Int. J. Sediment. Res. 34, 355–367 (2019).

Knack, I. M. & Shen, H. T. Sediment transport in ice-covered channels. Int. J. Sediment. Res. 30, 63–67 (2015).

Lau, Y. L. & Krishnappan, B. G. Sediment transport under ice cover. J. Hydraul. Eng. 111, 934–950 (1985).

Shields, A. Application of Similarity Principles and Turbulence Research to Bed-Load Movement. (1936).

Zhang, R. River Sediment Dynamics (China Water and Power, 1998).

Wang, X., Gualtieri, C. & Huai, W. Grain shear stress and bed-load transport in open channel flow with emergent vegetation. J. Hydrol. 618, 129204 (2023).

Xu, H., Lu, J. & Liu, X. Non-uniform sediment incipient velocity. Int. J. Sediment. Res. 23, 69–75 (2008).

Zhang, J. et al. An analytical study for predicting incipient motion velocity of sediments in ecological open channel flows. Phys. Fluids. 36, 046620 (2024).

Zhang, M. & Yu, G. Critical conditions of incipient motion of cohesive sediments. Water Resour. Res. 53, 7798–7815 (2017).

Wang, J., Sui, J. & Karney, B. W. Incipient motion of Non-cohesive Sediment under Ice Cover—An experimental study. J. Hydrodyn. 20, 117–124 (2008).

Ettema, R., Braileanu, F. & Muste, M. Method for estimating sediment transport in ice-covered channels. J. Cold Reg. Eng. 14, 130–144 (2000).

Knack, I. M. & Shen, H. T. A numerical model for sediment transport and bed change with river ice. J. Hydraul. Res. 56, 844–856 (2018).

Ettema, R. Review of alluvial-channel responses to River Ice. J. Cold Reg. Eng. 16, 191–217 (2002).

Kolerski, T. & Shen, H. Possible effects of the 1984 St. Clair River Ice Jam on Bed Changes. Can. J. Civ. Eng. 42, 696–703 (2015).

Smith, D. G. & Pearce, C. M. Ice jam-caused fluvial gullies and scour holes on northern river flood plains. Geomorphology 42, 85–95 (2002).

Sui, J., Karney, B. W., Sun, Z. & Wang, D. Field Investigation of Frazil Jam evolution: A Case Study. J. Hydraul Eng. 128, 781–787 (2002).

Sui, J., Hicks, F. & Menounos, B. Observations of riverbed scour under a hanging ice dam. Can. J. Civ. Eng. 33, 214–218 (2006).

Chien, N. & Wan, Z. Mechanics of Sediment Transport (American Society of Civil Engineers, 1999).

Muste, M., Braileanu, F. & Ettema, R. Flow and sediment transport measurements in a simulated ice-covered channel. Water Resour. Res. 36, 2711–2720 (2000).

Peters, M., Clark, S. P., Dow, K., Malenchak, J. & Danielson, D. Flow characteristics beneath a simulated partial ice cover: Effects of Ice and Bed Roughness. J. Cold Reg. Eng. 32, 04017017 (2018).

Einstein, H. A. Method of calculating the hydraulic radius in a cross section with different roughness. Appen. II of the paper formulas for the transportation of bed load. Trans. ASCE 107,561–597 (1942).

Bai, Y. & Duan, Y. The vertical distribution of suspended sediment and phosphorus in a channel with ice cover. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28, 37953–37962 (2021).

Sahu, S. N., Hossain, S., Sen, S. & Ghoshal, K. Sediment transport in ice-covered channel under non-equilibrium condition. Environ. Earth Sci. 83, 315 (2024).

Ghareh, A. et al. Estimation of composite hydraulic resistance in ice-covered alluvial streams. Water Resour. Res. 52, 1306–1327 (2016).

Zhu, Y. et al. Research on cohesive sediment erosion by flow: An overview. Sci. China Ser. E-Technol Sci. 51, 2001–2012 (2008).

Acknowledgements

The authors express their sincere gratitude to the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. U23A2012), Inner Mongolia Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. 2023QN05026), Inner Mongolia Agricultural University Excellent Doctoral Talent Project (Grant No. NDYB2022-28).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Hongchun Luo, writing-original draft, conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis; Honglan Ji, writing-review & editing, funding acquisition; Zijian Chen, data collection and editing; Bin Liu, visualization; Zhongshu Xue, validation; Zhijun Li, project administration.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Luo, H., Ji, H., Chen, Z. et al. An analytical study for predicting incipient motion velocity of sediments under ice cover. Sci Rep 15, 1912 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85884-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85884-5

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Effect of ice cover roughness on local scour around bridge piers

Scientific Reports (2026)

-

Ice velocity in the Yellow River bends using unmanned aerial vehicle imagery

Scientific Reports (2025)