Abstract

In Ethiopia, spicy hot red pepper, locally known as berbere, is a common food additive that is consumed in a variety of forms, which have high antioxidant potentials. The antioxidant activity of selected spices, such as garlic, ginger, cardamom, and black cumin, and hot red pepper (HRP) as well as both raw and cooked experimental and commercial spicy hot red pepper were evaluated using 2, 2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), 2’-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS), ferric ion (Fe3+) reducing antioxidant power (FRAP), and ferrous ion (Fe2+) chelating activity (FICA) assays. The IC50 of DPPH and ABTS of garlic were the lowest of all selected spices; conversely, they had the strongest free radical scavenging activities. The FRAP of ginger, and FICA of garlic were the strongest of all selected spices. The antioxidant potential of raw experimental (ESP), and commercial (CSP) spicy hot red pepper were stronger than the plain spices; however, cooked commercial spicy HRP or sauté (CSS) was the strongest of all following uncooked commercial spicy HRP (CSP). The DPPH and ABTS, and FRAP and FICA, respectively ranked in ascending order: HRP < ESP < ESS < CSP < CSS, and HRP < ESP < CSP ≤ ESS < CSS. Correlations between DPPH versus total flavonoid content (TFC), ABTS versus total phenolic content (TPC), FRAP versus TPC, and FICA versus condensed tannin content were strong in plain spices. The DPPH against TPC and TFC, ABTS against TFC, FRAP against TFC, and FICA against TPC correlated strongly in both raw and cooked spice mixture products. Spices used for popular Ethiopian spicy hot red pepper powder production, and both raw and cooked mixture of them are promising sources of antioxidants with positive health effects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Spices are used to reduce oxidative rancidity and minimize harmful substances, including heterocyclic amines1. Spices include certain bioactive compounds that have been attributed to the presence of antioxidants2,3, which scavenge free radicals in human bodies4. Natural antioxidants in herbs and spices include carotenoids, polyphenols, volatile oils1, and vitamins5.

Synthetic antioxidants like butylated hydroxyl toluene (BHT) and butylated hydroxyl anisole (BHA) used as primary antioxidants to arrest free radicals6. However, consumers prefer natural antioxidants due to their biological properties. Natural antioxidants have been discovered to exhibit a number of biological properties, including anticarcinogenic, antimutagenic, antidiabetic, hypolipidemic, and anti-inflammatory actions, in addition to preventing lipid oxidation in foods1. As a result, studies on natural, healthy, and nontoxic potential antioxidant additions are gaining popularity7. Spices can be used as drugs, flavoring, seasoning, coloring, and occasionally as preservatives. Due to the presence of phenolic antioxidative and antimicrobial components, spices have the capacity to preserve food8.

Natural antioxidant biomolecules that are either water-soluble or lipid-soluble are present in garlic (Allium sativum L.), ginger (Zingiber officinale Rosc.), black cumin (Nigella sativa L.), korarima (Aframomum corrorima (Braun) P.C.M. Jansen), hot red pepper (HRP), clove (Syzygium aromaticum), turmeric (Curcuma domestica), and black pepper9. Hot red peppers are valued for their aesthetic appeal, flavor, and health benefits, and are excellent sources of carotenoids, ascorbic acid, and polyphenols. Peppers also have functional, nutritional, and physiological importance10,11.

Many antioxidants are inactivated by heat treatment; however, some processing steps may improve the status of antioxidants by transforming them into more active compounds, like the deglycosylation of onion quercetin. Cooking causes compositional changes in peppers, such as capsaicinoid compounds11,12, and stewing increases antioxidant13. The effect of cooking on antioxidant activity is not always uniform and may be influenced by the food matrix, cooking method, and cooking duration11.

Hot red pepper, chili, and bell pepper are only a few of the peppers that Ethiopians produce and eat. Adult Ethiopians consume HRP at a higher rate compared to tomatoes and the majority of other vegetables14. Ginger, garlic, cardamom, and black cumin contributed enormous amounts to making spicy HRP. This study aimed to determine whether spices mixed with HRP to produce popular Ethiopian spicy HRPs strengthened both raw and cooked experimental spicy hot red pepper antioxidant potential.

Results and discussion

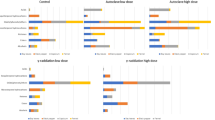

The DPPH radical scavenging activity of the spices arranged in descending order: garlic (67%) > cardamom (63%) > ginger (60%) > black cumin (56%) (Fig. 1a). Moreover, DPPH radical scavenging ability of HRP and spicy HRP was 67%, 63%, 59%, 57%, and 53%, respectively, for raw and cooked commercial and experimental spicy hot red pepper and HRP powder (Fig. 1b). The DPPH• radical scavenging activity (%) of the spices mixture and its cooked powder was significantly higher than that of individual spices, while weaker than that of the standard ascorbic acid. The study found that selected spices and their mixtures (raw and cooked), contained free radical scavengers or inhibitors, possibly acting as primary antioxidants. The DPPH+ radical concentration significantly reduced due to the spice extracts scavenging ability, which was dose-responsive.

The IC50 (inhibition concentrations) values for DPPH of the spices ranked in ascending order: garlic, cardamom, ginger, and black cumin (Table 1). However, the rankings reversed for DPPH radical scavenging activity (%). The IC50 of DPPH for powders of HRP and ESP, cooked experimental spicy hot red pepper or sauté (ESS), raw commercial spicy hot red pepper (CSP), and cooked commercial spicy hot red pepper or sauté powder (CSS) expressed as µg mL− 1 displayed in Table 2. The CSS ranked stronger than ESP and ESS in terms of their capacity to scavenge DPPH. However, their inverse relationship with the IC50 value of DPPH revealed that HRP > ESP > ESS > CSP > CSS and they were significantly (p < 0.05) different from one another.

The DPPH radical scavenging activity of the spices found to be concentration-dependent in spice extracts, meaning that as concentration increases, so does the radical scavenging potential15. The DPPH radical scavenging activity of garlic found to be weaker than previous studies of Eman et al.16 (11.4%), while ginger had a four-fold higher antioxidant scavenging capacity than previous studies of Idris et al.’s17, with an IC50 value of 625.7 µg mL− 1 in the ginger infusion. Cooking significantly increased the DPPH scavenging potential (p < 0.05) in experimental and commercial spice mixtures that agreed with Roncero-ramos et al.18. (11.20%). The study suggests that dried spice extracts contain compounds that can easily donate electrons or hydrogen and stabilize free radicals.

The IC50 value of the DPPH radical scavenging activity of garlic was lower than the findings of Lenkova et al.19 (17.17 mg mL− 1), indicating that the antioxidant scavenging potential of garlic was stronger than that of the work stated in the previous study. Compared to the present finding, the radical scavenging activity in garlic was stronger than Hasna et al.’s20 finding due to a higher IC50 value of DPPH = 1000. The trend observed in this study in plain spices15 finding that garlic had the weakest DPPH radical scavenging activity. The disparity might be attributed to different dryness levels and treatments of the ginger17. Little is known about the antioxidant activity of Aframomum corrorima, despite the fact that it is frequently utilized in Ethiopian food and traditional medicine21. Cardamom’s DPPH radical scavenging activity was lower than previously reported by Engeda et al.22 in cardamom seed powder (97 µg mL− 1). The IC50 value for DPPH radical scavenging activity was lower than that reported by Mariod et al.23 (2.26 mg mL− 1) in seedcake powder, and Dalli et al.’s24 report (3.8 mg mL− 1) of black cumin.

The study reveals that red pepper has a four times stronger DPPH radical scavenging activity than previous research by Sim and Sil25, with a IC50 of 772.68 µg mL− 1. The IC50 for DPPH in HRP was similar to Zhuang et al.’s26 value (190.70 µg mL− 1). The IC50 analysis demonstrated that ESP and CSP potential to scavenge free radicals were weak compared to Bag and Chattopadhyay’s27 study, the IC50 values of DPPH in µg mL− 1 for a mix of coriander and cumin (62.52), coriander and mustard (76.52), and cumin and mustard (80.42). The IC50 of DPPH in spicy HRP was higher compared to Loizzo et al.’s28 finding in Ethiopian spice blend, which contains almost similar amounts of allspice, cardamom or korarima, cloves, fenugreek, ginger, black pepper, and salt) (34.8 µg mL− 1). As a result, the IC50 of DPPH in ESP and CSP suggests that the antioxidant’s ability to scavenge free radicals is weaker than the previously reviewed data. Raw CSP found to be more effective at scavenging DPPH than raw ESP, but the IC50 in CSP was lower than in ESP. This could be due to differences in herbs and spices used, and partial fermentation processes used to produce CSP. Generally, these inconsistencies might be due to differences either in strength or in the concentration of reducing substances, mainly phenolic25, and differences in treatment, extraction techniques, and environmental conditions29. The present findings and review of previous studies, confirmed the hypothesis that the IC50 value is inversely related to antioxidant capacity30.

The study showed that garlic had a higher inhibitory potential than other spice samples at all concentrations, with a maximum percentage of inhibition of 61%, followed by cardamom (50%), ginger (54%), and black cumin (58%) (Fig. 2a). The ABTS scavenging potential of HRP, raw and cooked ESP, ESS, CSP, and CSS ranked in ascending order: HRP (55%) < ESP (61%) < ESS (63%) < CSP (65%) < CSS (69%) (Fig. 2b).

The IC50 of ABTS radical scavenging activity by garlic, ginger, cardamom, and black cumin was 64.76, 76.50, 84.77, and 75.52 µg mL− 1, respectively (Table 1). However, black cumin revealed strong antioxidant radical scavenging activity next to garlic with a significant (p < 0.05) difference, but both of them were significantly weaker than that of the Trolox reference standard (IC50 = 48.29 µg mL− 1). The IC50 values of ABTS in µg mL− 1 for HRP (77.63), ESP (62.31), ESS (61.00), CSP (56.11), and CSS (52.02) were significantly (p < 0.05) different (Table 2).

The IC50 value of CSS was the lowest of all; it had a much stronger free radical scavenging potential than the others but less than the Trolox (IC50 = 48.29 µg mL− 1). Similar to the ABTS scavenging potential, DPPH is concentration dependent. The ABTS radical scavenging activity (%) of garlic extract was weaker than Eman et al.’s16 finding. In general, the trends in ABTS scavenging ability of both raw and cooked extracts were similar to that of DPPH radical scavenging activity, which was consistent with Adefegha and Oboh31 findings in O. gratissimum extracts. However, the results of raw and cooked mixed products contradicted the findings of Hwang et al.11, who found that the ABTS radical scavenging activity of raw HRP reduced after cooking. This might be due to cooking factors (temperature, cooking time, and portion size).

Garlic has stronger ABTS antioxidant activity that supported by Shang et al.32. This study demonstrated significant antioxidant activity when compared to the earlier work of Otunola and Afolayan15 in garlic (IC50 of 0.66 mg mL− 1) and ginger (IC50 of 0.04 mg mL− 1). The ABTS radical scavenging activity of pepper was weaker than that of Otunola and Afolayan’s15, who discovered that the IC50 of 0.45 mg mL− 1. A similar result also noticed in a mixture of garlic, ginger, and pepper (IC50 = 0.10 mg mL− 1). The blend of garlic, ginger, and cayenne pepper has IC50 for DPPH and ABTS, respectively, < 31.2 and 68.75 mg mL− 1 33. The findings in spices mix powder was inconsistent with the findings of earlier work reviewed here. The ABTS radical scavenging activity in raw CSP was stronger than that of raw ESP; conversely, the IC50 of ABTS in CSP was lower than that of ESP. The antioxidant activity of CSS was greater than that of ESS. This could be due to types and proportions of herbs and spices mixed and the processing methods employed in CSP production.

The FRAP of ginger (98.52 mg TE g− 1) was comparably stronger than the other spices, which rated in descending order: garlic, black cumin, and cardamom, with a significant (p < 0.05) difference (Tables 1 and 2). The FRAP ranged from 91.12 to 94.68 mg TE g− 1, except for ESS and CSP; the others were significantly (p < 0.05) different from each other. Garlic showed better FRAP, which agreed with Shang et al.32. The FRAP of the ginger was lower than that of other studies by Amirul et al.34. (330 mg TE g-1). As far as it is known, no previous study examined the antioxidant potential of cardamom using the FRAP assay. The black cumin showed significant antioxidant activity similar to Dalli et al.24. The reducing activity of HRP was weaker than that reported by Amirul et al.34. on the same species of chili burung (439 mg TE g− 1). The FRAP was weaker than that of Otunola and Afolayan’s15 finding on an extract of mixture of garlic, ginger, and pepper. This is similar to experimental and commercial spices mix powders. The uncooked CSP showed a greater ability to reduce FRAP than the uncooked ESP. The stronger reducing power perceived in CSP was possibly due to the excessive concentration of reducers in its powder than in ESP, which agreed with Akhtar et al.35. The reason may be the type and quantity of herbs and spices used to make CSP, and partial fermentation. The inconsistencies between the studies may be attributed to the form of spices (dry or fresh), the parts of spices used (root, bulb, or leaf), and extraction techniques17,36.

The FICA in mg QE g− 1 for spices ranked in the following order: cardamom, ginger, black cumin, and garlic, but garlic and ginger were statistically different at p < 0.05 (Tables 1 and 2). The HRP and spicy HRPs had FICA ranging from 23.33 to 25.40 mg QE g− 1, which was significantly (p < 0.05) different from one another; however, ESS, CSP, and CSS revealed no difference. The present finding was in-line with the findings of Chan et al.37, who discovered that six of the 26 ginger species (Curcuma longa, Kaempferia galanga, Alpinia galanga, Etlingera elatior, Zingiber spectabile, and Etlingera maingayi) had the strongest ferrous ion chelating ability. The FICA of cardamom was higher than Ali et al..’s36 report on the same genera of cardamom, but the findings for black cumin was weaker than that report presented by the same author, and the results in HRP were more effective than black pepper (the same species). All raw ESP and CSP showed a significant increase in FICA as compared to plain spices, which confirmed by Shaimaa et al.38. Uncooked CSP had a somewhat stronger FICA than uncooked ESP. Additional chelators that exist in mixed herbs and spices that may result in high concentrations may cause the chelating potential of CSP, which supported by Akhtar et al.35. The types and quantities of herbs and spices used to manufacture CSP, as well as partial fermentation, may cause variances. Generally, dissimilarities in all assays might be associated with maturity stages and environmental conditions36,37.

The effects of cooking on the antioxidant capacities may differ depending on cooking method, localization of the structures and conditions (temperature, cooking time, portion, cutting, presence of oxygen and water), and pH values39. In this investigation, while cooking decreased the IC50 of DPPH in spices mix between ESP and ESS = 5.41% and between CSP and CSS = 67.52%, cooking strengthened and improved the samples capacity to scavenge free radicals. This conclusion also validated by Adegoke et al.40. in all cooked paste samples. In this study, the cooked spices mix’s antioxidant activities (DPPH, ABTS, FRAP, and FICA) increased, which was consistent with Shaimaa et al.38. Spices mix showed stronger antioxidant activity when cooked than raw, which was in-line with Ornelas-Paz et al.29 that boiling jalapeno peppers increased their antioxidant activity.

However, study by Zhao et al.41 found that coagulation following heating could reduce extraction ability and reduce free radical scavenging activity. Boiling had a slight negative impact on antioxidant activity and that antioxidant compounds leaching into the cooking water may have brought about this negative impact. Hwang et al.11 found that boiling, steaming, microwave heating or baking, stir-frying, or roasting weakened the antioxidant capabilities of HRPs. Cooking losses cause antioxidants to be released, destroyed, or created as redox active metabolites42. Cooked CSS demonstrated the highest antioxidant activity among plain spices, and raw and cooked spices mix powders. However, it performs weaker than the reference standard ascorbic acid (IC50 = 26.26 µg mL− 1). This might be because commercial spices mix HRP powder contains additional types of herbs and spices, different mixed proportions, partial fermentation, and they may contain more water-soluble extractable bioactive compounds. The cooking effect on antioxidant capacity is not always constant, which might be associated with the nature of the food matrix and the type of cooking method43. Furthermore, the type and physical form of the sample, genetics, environmental conditions, and analytical methods, a loosening of antioxidant moieties, dehydration of the food matrix, improved extractability of antioxidant compounds such as phenols29, or leaching of antioxidant compounds into the cooking water when decanting is involved as a cooking method41.

The phytochemicals that did not exhibit a correlation with antioxidant activity at p < 0.05 excluded (data not shown). The results of the study indicate that there were significant differences between the raw powder forms of spices and HRP as well as raw and cooked powders of the mixture. However, the cooked mixture or sauté powders showed the greatest increase in phytochemical content following the raw mixture powders. There was no significant difference in the TPC of major spices ranging from 12.77 to 13.13 mg GAE g− 1 between garlic and ginger, and cardamom and black cumin. There was a significant (p < 0.05) difference in the TFC of black cumin, ginger, garlic, and cardamom, respectively, 12.92, 12.73, 12.65, and 12.43 mg QE g− 1. The TPC for HRP, ESP, ESS, CSP, and CSS were 0.43, 13.62, 14.21, 13.76, and 13.96 mg GAE g− 1, respectively, with a significant difference between ESS, ESP, and HRP at p < 0.05. The TFC ranked in ascending order from 13.21 to 15.14 mg QE g− 1, with significant (p < 0.05) differences. Phytochemical content arranged in ascending order: CSS > CSP > ESS > ESP > plain spices including HRP. Flavonoids and other phytochemicals like phenolics better found in mixture powders, both raw and cooked, than in plain spices. The study’s findings provided valuable insights into the potential benefits of mixing and cooking spices to enhance the phytochemical content of spicy HRP. The TPC and TFC increased for both uncooked and cooked spice mixture HRP powders, which agreed with Shaimaa et al.38. that TPC and TFC increased after boiling for Thai red curry paste and sweet and chili pepper, respectively. This may be because spices milling-based mixing and cooking the resulting mixture, degrades spices cell wall and increases surface area, which improves the efficiency of phytochemical extraction and increases the phytochemical content of both raw and cooked ESP, ESS, CSP, and CSS, a popular Ethiopian food additive, promising sources of phytochemicals when compared to spices alone. This is true if and when decanting is not used as cooking technique44.

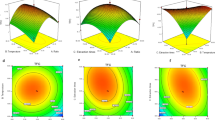

The percentage DPPH free radical scavenging activity, FRAP, and FICA found to have a very strong correlation with TFC and total saponins, TPC, and CTC, respectively, with a correlation coefficient (r) greater than 0.84, but the correlation between FICA and CTC was negative. On the other hand, there was a very weak correlation between percentage ABTS radical scavenging activity and TPC (Fig. 3). The DPPH and ABTS radical scavenging activities (%) showed a very strong correlation with TPC (r = 0.9360) and TFC (r = 0.9565), as well as TFC (r = 0.9207) and CTC (r = 0.8258), respectively. The FRAP and FICA were very strongly correlated with TPC and TFC, with a correlation coefficient (r) greater than 0.89 (Fig. 4).

The positive correlation between DPPH radical scavenging activity (%) against TFC and total saponins, ABTS radical scavenging activity (%) and TPC, FRAP, and TPC, as well as FICA and CTC, suggested that TPC, TFC, total saponins, and CTC of selected spices associated with primary antioxidant activities (DPPH, ABTS, and FRAP), as well as secondary antioxidant activities (FICA). The current finding in spices was consistent with previous research by Zhang et al.45. revealed that free radical scavenging activity was positively correlated with TPC and TFC. The weak relationship between the percentages of ABTS scavenging potential and TPC in selected spices played a weak role in ABTS radical scavenging activity. The negative correlation between FICA and CTC suggests that CTC reduced effect on FICA, which agreed with Giulia and Roberto’s10 findings. The current finding was in-line with the previous study done by Ali et al.36 who reported a strong correlation between DPPH, ABTS, FRAP and FICA, and TFC, suggesting that higher TFC levels have a powerful ability to scavenge DPPH and ABTS, reduce FRAP, and chelate FICA in spicy HRP. The relationship between DPPH radical scavenging activity (%) and TPC in this study is stronger than that found by Jelena et al.46 (r = 0.7071), suggesting that sterols, tocopherols, ascorbic acid, and carotenoids may be the primary antioxidants rather than phenolics. The DPPH and ABTS radical scavenging activities (%) strongly correlated with TFC, as well as FRAP with TPC, which agreed with the correlation analysis of Zhang et al.45.

The current finding was in-line with the finding of Derbie et al.47, observed a very strong correlation between ABTS and DPPH radical scavenging activities. The correlation result of FRAP and ABTS radical scavenging activity (%) was very strong, which agreed with Jelena et al.46. This is because ABTS radical scavenging activity and FRAP use a similar redox reaction47. The correlation between FICA versus DPPH radical scavenging activity (%) and FRAP was very strong, and it agreed with the findings of Jelena et al.46. The differences between studies could be attributed to the variety of tested samples, concentrations, and antioxidant activity assays used.

Conclusion

The study found that cooked spicy HRPs have stronger antioxidant activity than raw spices mixtures. Next to the cooked spices mixture, the raw spices mixture demonstrated a significant increase in antioxidant activity in all assays. The strong correlation observed between antioxidant activities (DPPH, ABTS, FRAP, and FICA) and the levels of TPC, TFC, CTC, and total saponins in both plain and mixed spices further supports the role of polyphenols as a source of antioxidants in spicy HRP. Overall, the study concludes that milling-based mixing spices and water assisted cooking, particularly stewing, the resulting mixture significantly strengthens the antioxidant potential of both experimental and commercial spicy HRPs. This makes mixed and cooked spice mixtures a preferred choice over plain spices alone as a food additive. Moreover, the bioactive compounds found in spices and spicy HRPs have the potential to serve as natural alternatives to controversial synthetic antioxidants (BHT and BHA), which are commonly used as food additives.

Materials and methods

Sample preparations extraction

Fresh garlic, ginger, cardamom, black cumin, dry HRP, and commercial spicy hot red pepper powder collected from small- and medium-scale spice processors in Hawassa, Ethiopia. The samples cleaned, sun dried and ground finely. A 100% plain HRP, garlic, ginger, cardamom, and black cumin powders prepared, and a portion of it proportionately mixed at 67.5%, 13.5%, 9.5%, 6.8%, and 2.7%, respectively, which referred to as raw experimental spicy hot red pepper (ESP) powder48,49. A portion of experimental and commercial spicy HRP powders cooked with water, simmered at 85℃ at the seventh minute, and called cooked spicy HRP or sauté. The sauté made without the use of preliminary ingredients used to make Ethiopian stew. The sauté was oven dried and finely ground. The samples sieved, packed, and stored for extraction.

A finely milled 2 g of each raw and cooked sample mixed with 40 mL of ethanol: H2O (70: 30, v/v). The contents shook for 8 h using an orbital shaker (GFL 3005, GEMINI, Apeldoorn, Netherlands), with a speed of 120 rpm at room temperature. The solution filtered using Whatman No. 1 filter paper and evaporated at 50 °C under reduced pressure in a rotary vacuum evaporator (Buchi, 3000 series, Switzerland). Stock solutions of different extracts performed in triplicate with 70% aqueous ethanol (v/v) at a concentration of 5 mg mL[− 1 35, 50. The working solutions for antioxidant activity analysis prepared from various extract stock solutions at different concentrations. The stock and working solutions stored in sealed amber bottles at -20℃ until further investigation.

2, 2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl, or 1, 1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) free radical scavenging activity assay

When the DPPH scavenged by an antioxidant through hydrogen donation or radical scavenging ability to form a stable DPPH, resulting in reduced or non-radical form DPPH-H, the color changed from purple (DPPH) to a reduced yellow (2, 2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazine) molecule. The absorbance reduction measured at wavelength 517 nm by the DPPH assay (Sigma-Aldrich, AppliChem, Darmstadt, Germany). The DPPH radical scavenging activity (%) is widely used to evaluate the free radical scavenging activity of many plant extracts36, with some modifications. Various extract concentrations (ranging from 25 to 250 µg mL− 1) put into different test tubes. A freshly prepared 1 mL of 0.004% DPPH solution (w/v) added to each of the test tubes. The solvent manually shook into the test tubes until the necessary volume of solution (4 ml) reached. The reaction mixture and the ascorbic acid (C6H8O6) reference standard (Sigma Aldrich AppliChem, Darmstadt, Germany) vortexed and left to stand at room temperature in the dark for 30 min. The absorbance of the final solution measured at 517 nm against the blank using a Thermo Scientific Multiscan Go Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Oy, Ratastie, Finland). Methanol used as an absolute blank. The reaction mixture without a sample developed the most intense color (the color changes from violet to yellow on reduction by hydrogen or electron donation). The color decreased with an increasing volume of extract added.

The half-maximum inhibitory concentration (IC50) is the quantity of antioxidants required to reduce the stable and purple-colored, DPPH radical into yellow 2, 2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazine to reach 50% reduction. The values of the samples that caused 50% inhibition (IC50 value) calculated using a linear regression plot of percentage inhibition against the concentration of the extract (50 to 250 µg mL− 1). Antioxidants that possess stronger scavenging abilities have lower IC50 values2.

2, 2’-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS+) free radical scavenging activity assay

The food industry and agricultural researchers frequently use the ABTS assay to evaluate the antioxidant capacities of foods12. The ABTS method is well known for being a quick method for determining antioxidant activity and could be a convenient instrument for screening samples and varieties in order to obtain high levels of natural antioxidants in foods38. The ability to scavenge free radicals assessed using the ABTS radical cation converted back to decolorization during this test. The reaction between 7 mM ABTS in water and 2.45 mM potassium persulfate (1:1) produced blue-green ABTS.+, which then stored at room temperature in the dark for 12 to 16 h before use. The radical scavenging activity experiment measured at 734 nm using a microplate well12 with some modifications. A 200 µL ABTS working solution and a 10 µL extract solution at various concentrations added to the container, shaken well, and protected from light for 7 min. The absorbance measured at 734 nm using Thermo Scientific Multiscan Go Spectrophotometer. Trolox (6-hydroxy-2, 5, 7, 8-tetramethylchroman-2-carboxylicmacid (Sigma Aldrich, AppliChem, Darmstadt, Germany), a water-soluble analog of Vitamin E, served as the reference standard and distilled water as the blank. For this test, the extract solution diluted to have an absorbance value ranging from 0.2 to 0.8. The ABTS radical scavenging activity (%) calculated using the formula below:

The IC50 value of the ABTS+ (bluish-green) radical calculated by constructing a standard curve (percentage inhibition against concentration of the extract (15 to 90 µg mL− 1) using a linear regression equation 9,12.

Ferric ion (Fe3+) reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) assay

The FRAP assays method involves a single electron reaction between ferric ion (Fe3+) and single electron donor antioxidants. It is based on the reduction of the complex of ferric iron and 2, 3, 5-triphenyl-1, 3, 4- triaza-2-azoniacyclopenta-1, 4-diene chloride (TPTZ) to the ferrous form at low pH. With a few modifications, the FRAP experiment carried out in accordance with Munteanu and Apetrei51. The antioxidants reduce ferric tripyridyltriazine (Fe3+-TPTZ) to the blue-colored complex ferrous tripyridyltriazine (Fe2+-TPTZ), which serves as the foundation of the FRAP assay method. Free radical chain breaking takes place by donating a hydrogen atom. A 96-well plate filled with 180 µL of the FRAP assay working solution (300 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 3.6), 10 mM TPTZ, and 20 mM (FeCl3) in the ratio of 10:1:1 (v: v: v)), and 5 µL of each extract added, shaken well, and then incubated at 37 °C for 15 min in a dark place. The absorbance measured at a wavelength of 593 nm using Thermo Scientific Multiscan Go Spectrophotometer. As the reference standard and the blank, respectively, Trolox and distilled water used. The Trolox concentration selected with an absorbance value range of 0.2 to 0.8 to generate a standard curve. The FRAP determined by constructing the standard curve against Trolox (y = 0.0238x + 0.2199, R2 = 0.9648; y = absorbance, x = concentration obtained from the Trolox calibration curve (µg mL− 1), and R2 = the square of the correlation coefficient, r). The FRAP antioxidant activity assay in terms of milligrams of Trolox equivalent per gram (mg TE g− 1) of dry extract calculated using the equation:

where C stands for FRAP (mg TE g-1). c stands for the concentration obtained from the Trolox calibration curve (µg mL-1). V stands for volume of extract solution in milliliters. m stands for the weight of dry extract in grams.

Ferrous ion (Fe2+) chelating activity (FICA) assay

The FICA of the prepared extracts measured using a modified version of the Sudan et al.52 methods. The ferrozine complex containing Fe2+ at 562 nm absorbance used to measure the extract’s capacity to chelate Fe2+. Chelating agents, on the other hand, prevent the formation of complexes; as a result, the red color of the complex is decreased. Therefore, measuring color reduction allows the estimation of the coexisting chelator’s chelating activity. Briefly, 100 µL of each test extract (1 mg mL-1) took and raised to 3 mL with methanol. Methanol (740 µL) added to 20 µL of 2 mM FeCl2. The reaction initiated by the addition of 40 µL of 5 mM ferrozine to the mixture. After 10 min of incubation at room temperature, the mixture’s absorbance measured at 562 nm using Thermo Scientific Multiscan Go Spectrophotometer. Distilled water served as the blank, which used for error correction due to the unequal color of the sample solutions. The FICA quantified by constructing a standard curve against quercetin (y = 0.0885x + 0.3578, R2 = 0.9803).

The FICA antioxidant activity assay expressed using mg QE g− 1 of dry extract, and the results calculated as follows:

Where C = FICA (mg QE g-1). c = concentration obtained from the quercetin calibration curve (µg mL− 1). V = volume of extract solution in milliliters. m = weight of dry extract in grams.

Phytochemical content

The study investigated the phytochemical content of raw spices, HRP, and raw and cooked spicy HRP powders, for a correlation study with antioxidant activity. Total phenolic content (TPC), total flavonoid content (TFC), condensed tannin content (CTC), and total saponins determined, respectively, by the Folin-Ciocalteu36,53, aluminum chloride (AlCl3)36,54, vanillin condensation55,56, and the gravimetric40,56 methods.

Experimental design and statistical analysis

A study conducted in Hawassa, Ethiopia, using a preliminary survey to select spice locations, varieties, and processing enterprises. Six medium- and small-scale enterprises selected and samples collected using simple random sampling. Simple random sampling then used to collect samples from the identified businesses. The experimental design was a completely randomized design, with factorial treatment combinations affecting phytochemical content and antioxidant activity. Statistical analysis performed using SAS JMP_14 software (Cary, North Carolina, USA) and Tukey’s HSD multiple rank test at a significance level of p < 0.05. The results presented as the mean ± SD.

Data availability

All relevant data of this article is included within the article.

References

Brewer, M. S. Natural antioxidants: Sources, compounds, mechanisms of action, and potential applications. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 10 (4), 221–247. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-4337.2011.00156.x (2011).

Ene-obong, H., Onuoha, N., Aburime, L. & Mbah, O. Chemical composition and antioxidant activities of some indigenous spices consumed in Nigeria. Food Chem. 238 (1), 58–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.12.072 (2018).

Macario, E. et al. Agroindustrial science escuela de ingeniería agroindustrial garlic (Allium sativum L) and its beneficial properties for health: A review el ajo (Allium sativum L) y sus propiedades beneficiosas para la salud: Una revisión. Agroindustrial science 10 (1), 103–115 (2020). https://doi.org/10.17268/agroind.sci.2020.01.15

Thandiwe Alide, P., Wangila & Kiprop, A. Effect of cooking temperature and time on total phenolic content, total flavonoid content and total in vitro antioxidant activity of garlic. BioMed. Cent. Res. Notes. 13, 564. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-020-05404-8 (2020).

Daniel, A. Review on use of bioactive compounds in some spices in food preservation. Food Sci. Qual. Manag. 87 (5), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.7176/FSQM (2019).

Leykun Tigist Senay. Systematic review on spices and herbs used in food industry. Am. J. Ethnomed. 7 (5), 20. https://doi.org/10.36648/2348-9502.7.1.20 (2020). http://www.imedpub.com/ethnomedicine/

Altemimi, A. et al. Extraction, isolation, and identification of bioactive compounds from plant extracts. Plants 6(4), 38–42 (2017). https://doi.org/10.3390/plants6040042

Qing Liu, X. et al. Antibacterial and antifungal activities of spices. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18, 1283. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18061283 (2017).

Embuscado, M. E. Spices and herbs: natural sources of antioxidants: A mini review. J. Funct. Foods. 18, 811–819. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jff.2015.03.005 (2015).

Giulia, B. & Roberto, L.S. Characterization of hot red pepper spice phytochemicals, taste compounds content and volatile profiles in relation to the drying temperature. J. Food Biochem. 42, 2675. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfbc.12675 (2018).

Hwang, I. G., Shin, Y. J., Lee, S., Lee, J. & Yoo, S. M. Effects of different cooking methods on the antioxidant properties of hot red pepper (Capsicum annuum L). Prev. Nutr. Food Sci. 17 (4), 286–292. https://doi.org/10.3746/pnf.2012.17.4.286 (2012).

Hamed, M., Kalita, D., Bartolo, M. E., Jayanty, S. S. & Capsaicinoids polyphenols and antioxidant activities of Capsicum annuum: Comparative study of the effect of ripening stage and cooking methods. Antioxidants 8 (9), 2–17. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox8090364 (2019).

Opara, E. I. & Chohan, M. Culinary herbs and spices: Their bioactive properties, the contribution of polyphenols and the challenges in deducing their true health benefits. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 15 (10), 19183–19202. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms151019183 (2014).

Wubalem, G. A seminar review on hot red pepper (Capsicum) production and marketing in Ethiopia. Cogent Food Agric. 5, 2–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2019.1647593 (2019).

Otunola, G. A. & Afolayan, A. J. Evaluation of the polyphenolic contents and some antioxidant properties of aqueous extracts of garlic, ginger, cayenne pepper and their mixture. J. Appl. Bot. Food Qual. 86, 66–70. https://doi.org/10.5073/JABFQ.2013.086.010 (2013).

Eman, M., Hegazy, A., Sabry, Wagdy, K. B. & Khalil Neuroprotective effects of onion and garlic root extracts against Alzheimer’s disease in rats: Antimicrobial, histopathological, and molecular studies. J. Biotechnol. Comput. Biol. Bionanotechnol.. 103 (2), 153–167. https://doi.org/10.5114/bta.2022.116210 (2022).

Idris, N. A., Yasin, H. M. & Usman, A. Heliyon voltammetric and spectroscopic determination of polyphenols and antioxidants in ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe). Heliyon 5(3), e01717 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e01717

Roncero-ramos, I., Mendiola-lanao, M., Pérez-clavijo, M. & Delgado-andrade, C. Effect of different cooking methods on nutritional value and antioxidant activity of cultivated mushrooms. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 68 (3), 287–297. https://doi.org/10.1080/09637486.2016.1244662 (2017).

Lenkova, M., Bystrická, J., Tóth, T. & Hrstkova, M. Evaluation and comparison of the content of total polyphenols and antioxidant activity of selected species of the genus Allium. J. Cent. Eur. Agric. 17 (4), 1119–1133. https://doi.org/10.5513/JCEA01/17.4.1820 (2016).

Hasna Bouhenni, N. K. et al. Analysis of bioactive compounds and antioxidant activities of cultivated garlic (Allium sativum L.) and red onion (Allium cepa L.) in Algeria. Int. J. Agric. Environ. Food Sci. E-ISSN. 4 (10), 550–560. https://doi.org/10.31015/jaefs.2021.4.15 (2021).

Eyob, S., Appelgren, M., Rohloff, J., Tsegaye, A. & Messele, G. Traditional medicinal uses and essential oil composition of leaves and rhizomes of korarima (Aframomum corrorima (Braun) P.C.M. Jansen) from southern Ethiopia. S. Afr. J. Bot. 74(2), 181–185. (2008). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sajb.2007.10.007

Engeda Dessalegn, G., Bultosa, G. D., Haki, Chen, F. & Rupasinghe, H. P. V. Antioxidant and cytotoxicity to liver cancer HepG2 cells in vitro of korarima (Aframomum corrorima (Braun) P.C.M. Jansen) seed extracts. Int. J. Food Prop. 25 (1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/10942912.2021.2019268 (2022).

Mariod, A. A., Ibrahim, R. M., Ismail, M. & Ismail, N. Antioxidant activity and phenolic content of phenolic rich fractions obtained from black cumin (Nigella sativa) seedcake. Food Chem. 116 (1), 306–312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.02.051 (2009).

Dalli, M. et al. Nigella sativa L. phytochemistry and pharmacological. Biomolecules 12 (12), 12–20. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom12010020 (2022).

Sim, S. K. H. & Sil, H. Y. Antioxidant activities of hot red pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) pericarp and seed extracts. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 43 (10), 1813–1823. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2621.2008.01715.x (2008).

Zhuang, Y., Chen, L., Sun, L. & Cao, J. Bioactive characteristics and antioxidant activity of nine peppers. J. Funct. Foods. 4 (1), 331–338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jff.2012.01.001 (2012).

Bag, A. & Chattopadhyay, R. R. Evaluation of synergistic antibacterial and antioxidant efficacy of essential oils of spices and herbs in combination. PLoS ONE. 10 (7), 11–17. https://doi.org/10.1371/J.pone.0131321 (2015).

Loizzo, M. R. et al. In vitro antioxidant and hypoglycemic activities of Ethiopian spice blend berbere. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 62 (7), 740–749. https://doi.org/10.3109/09637486.2011.573470 (2011).

Ornelas-Paz, J. et al. J. D. Effect of cooking on the capsaicinoids and phenolics contents of Mexican peppers. Food Chem. 119(4), 1619–1625 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.09.054

Hossain, M. B., Brunton, N. P., Barry-Ryan, C., Martin- Diana, A. B. & Wilkinson, M. Antioxidant activity of spice extracts and phenolics in comparison to synthetic antioxidants. Rasayan J. Chem. 1 (4), 751–756 (2008).

Adefegha, S. A. & Oboh, G. Phytochemistry and mode of action of some tropical spices in the management of type-2 diabetes and hypertension. Afr. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 7 (7), 332–346. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJPP12.014 (2013).

Shang, A. et al. Bin. Bioactive compounds and biological functions of garlic (Allium sativum L.). Foods 8(7), 2–30 (2019). https://doi.org/10.3390/foods8070246

Gloria, A. O. & Anthony, J. A. In vitro antibacterial, antioxidant and toxicity profile of silver nanoparticles greensynthesized and characterized from aqueous extract of a spice blend formulation. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 32 (3), 724–733. https://doi.org/10.1080/13102818.2018.1448301 (2018).

Amirul, A. M. D. et al. Evaluation of phenolics, capsaicinoids, antioxidant properties, and major macro-micro minerals of some pungent and sweet peppers and ginger land-races of Malaysia. J. Food Process. Preserv. 10 (3), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/jf14483 (2020).

Akhtar, N., Ihsan-ul-Haq & Mirza, B. Phytochemical analysis and comprehensive evaluation of antimicrobial and antioxidant properties of 61 medicinal plant species. Arab. J. Chem. 11 (8), 1223–1235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2015.01.013 (2018).

Ali, A. et al. F. R., and R. Comprehensive profiling of most widely used spices for their phenolic compounds through lc-esi-qtof-ms2 and their antioxidant potential. Antioxidants 10 (5), 717–721 (2021). https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox10050721

Chan, E. W. C. et al. Effects of different drying methods on the antioxidant properties of leaves and tea of ginger species. Food Chem. 113, 166–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.07.090 (2009).

Shaimaa, G. A., Mahmoud, M. S. & Mohamed, M. R. Effect of heat treatment on phenolic and flavonoid compounds and antioxidant activities of some Egyptian sweet and Chilli pepper. Nat. Prod. Chem. Res. 4 (3), 2–5. https://doi.org/10.4172/2329-6836.1000218 (2016).

Swati, Banerjee & Adak, K. Effect of cooking temperature and time period on phytochemical content and in vitro antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity of the leaf extracts of typhonium trilobatum (a less focussed edible herbal plant). Int. J. Sci. Res. (IJSR). 1, 2319–7064. https://doi.org/10.21275/art20164457 (2017).

Adegoke, B. H., Adedayo, A. E., Temilola, D. & Proximate Phytochemical and sensory quality of instant pepper soup mix. J. Culin. Sci. Technol. 14 (1), 59–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/15428052.2015.1080642 (2016).

Zhao, C. et al. Effects of domestic cooking process on the chemical and biological properties of dietary phytochemicals. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 85 (7), 55–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2019.01.004 (2019).

Do, T. N. & Hwang, E. Effects of different cooking methods on bioactive compound content and antioxidant activity of water spinach (Ipomoea aquatica). Food Sci. Biotechnol. 24 (3), 799–806. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10068-015-0104-1 (2015).

Elizabeth, I., Opara & Chohan, M. Culinary herbs and spices: Their bioactive propertis, the contribution of polyphenols and the challenges in deducing their true health benefits. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 15, 19183–19202. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms151019183 (2014).

Alide, T., Wangila, P. & Kiprop, A. Effect of cooking temperature and time on total phenolic content, total flavonoid content and total in vitro antioxidant activity of garlic. BioMed. Cent. Res. Notes. 13 (2), 3–6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-020-05404-8 (2020).

Zhang Ruifen, Q. et al. Phenolic profiles and antioxidant activity of litchi pulp of different cultivars cultivated in Southern China. Food Chem. 136 (10), 1169–1176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.09.085 (2013).

Jelena, S. et al. Stojanovic. Chemometric characterization of twenty-three culinary herbs and spices according to antioxidant activity. J. Food Meas. Charact. 13, 2167–2176. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11694-019-00137-0 (2019).

Derbie, A., Assefa, Young–Soo, K. & Ramesh, K. Saini. A comprehensive study of polyphenols contents and antioxidant potential of 39 widely used spices and food condiments. J. Food Meas. Charact. 12 (3), 1548–1555. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11694-018-9770-z (2018).

Medalcho, T. H., Ali, K. A., Augchew, E. D. & Mate, I. J. Aflatoxin B1 detoxification potentials of garlic, ginger, cardamom, black cumin, and sautéing in ground spice mix red pepper products. Toxins 15, 307. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins15050307 (2023).

Medalcho, T. H., Ali, K. A., Augchew, E. D. & Mate, I. J. Effects of spices mixture and cooking on phytochemical content in Ethiopian spicy hot red pepper products. Food Sci. Nutr. 00, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1002/fsn3.3886 (2023).

Gupta, D. Methods for determination of antioxidant capacity: A review. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 6 (2), 546–566. https://doi.org/10.13040/IJPSR.0975-8232.6 (2015).

Munteanu, I. G. & Apetrei, C. Analytical methods used in determining antioxidant activity: A review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 3380–3410. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22073380 (2021).

Sudan, R., Bhagat, M., Gupta, S., Singh,Journal & Koul, A. Iron (FeII) chelation, ferric reducing antioxidant power, and immune modulating potential of Arisaema jacquemontii (himalayan cobra lily). Biomed. Res. Int. 5, 6. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/179865 (2014).

Guldiken, B. et al. Phytochemicals of herbs and spices: Health versus toxicological effects. Food Chem. Toxicol. 119 (7), 37–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fct.2018.05.050 (2018).

Petra, M., Marija, S. & Lidija, J. Validation of spectrophotometric methods for the determination of total polyphenol and total flavonoid content. J. Assoc. Anal. Chem. Int. 100 (6), 1795. https://doi.org/10.5740/jaoacint.17-0066 (2017).

Jaadan, H. et al. Phytochemical screening, polyphenols, flavonoids and tannin content, antioxidant activities and FTIR characterization of Marrubium vulgare L. from 2 different localities of Northeast of Morocco. Heliyon 6 (11), e05609. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e05609 (2020).

Udu-Ibiam, O. E. et al. Phytochemical and antioxidant analyses of selected edible mushrooms, ginger and garlic from Ebonyi State, Nigeria. IOSR J. Pharm. Biol. Sci. 9 (3), 86–91. https://doi.org/10.9790/3008-09348691 (2014).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the Public University of Navarra (UPNA) for the laboratory experimental work permission particularly Prof. Juan Mate for his supply of consumables, and Dr. Idoya Fernández for her facilitation. We thank Dr, Tadesse Fikre for his software technical support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, T.H.M., K.A.A. and E.D.A.; methodology, T.H.M., E.D.A.; software, T.H.M.; validation, T.H.M. and E.D.A.; formal analysis, T.H.M.; investigation, T.H.M.; resources, T.H.M.; data curation, T.H.M.; writing—original draft preparation, T.H.M.; writing—review and editing, T.H.M. and E.D.A.; visualization, T.H.M.; supervision, K.A.A. and E.D.A.; project administration, T.H.M.; funding acquisition, T.H.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Medalcho, T.H., Ali, K.A. & Augchew, E.D. Effects of spices mixture and cooking on antioxidant activity in Ethiopian spicy hot red pepper powder. Sci Rep 15, 5203 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85952-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85952-w