Abstract

Microglia are heterogeneous macrophage cells that serve as the central nervous system’s resident immune cells. During neuro-related diseases, CNS resident macrophages change their molecular, cellular, and functional properties—that collectively define “states”—in response to specific neural perturbations. Neurovascular diseases elicit state changes, by promoting increased vascular permeability among microvessels and thus altering blood–brain barrier integrity. Here, we used a mouse model of brain arteriovenous malformation (bAVM)—mediated by endothelial loss of Recombination signal binding protein for immunoglobulin kappa J region (Rbpj)—to investigate changes to brain resident macrophage states during neurovascular disease pathogenesis. We found increased area of Ionized calcium-binding adapter molecule 1 (Iba1) expression in Rbpj-deficient bAVM tissue, as well as Iba1 + cell hypertrophy, increased cell number, and hyperproliferation within areas of increased Iba1 + density. Hypertrophic cells had increased cell body areas and decreased process length, suggesting a transition in surveillance state. Gene expression data revealed region-specific molecular changes to Iba + cells, suggestive of altered metabolic activity. CNS resident macrophages isolated from cortical and cerebellar regions showed profiles consistent with cytokine-associated immunogenic responses and an immunovigilant pathogen-recognition response, respectively. Thus, our findings demonstrate region-specific changes to CNS resident macrophages during Rbpj-deficient bAVM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Microglia are a subset of motile macrophages that alter their physiological states to contribute to the maintenance of central nervous system (CNS) homeostasis. In select states, microglia provide immunogenic surveillance, while in others, microglia initiate appropriate immune responses. Microglia are known to react to neuropathological conditions—those altered states, which were previously identified as “reactive,” “M1/M2,” or “pro-inflammatory (neurodegenerative/neurotoxic) and anti-inflammatory (neuroprotective),” provide critical information about possible changing roles for microglia during disease1. More recently, the field has shifted from this binary, inflammation-centered classification toward a more spectrum-based classification to include intermediate and overlapping phenotypes, as well as newly emerging molecular, cellular, and functional factors associated with microglial activation2,3,4. In some states, microglia produce chemokines and cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) and various interleukins as part of a pro-inflammatory response5 and express select genes CD11, CD32 and CD866, while in other states, microglia produce anti-inflammatory factors such as interleukin (IL) 10 and express genes such as CD2066. While such expression profiles among microglial populations contribute to an understanding about the cell state, other cellular features must also be considered. Changes in cell biological properties, including altered morphology, proliferation, and migratory behaviors can also be assessed7. Surveillant microglia typically have a relatively small cell body and long cytoplasmic processes; however, those morphological properties may change, as microglia may retract their processes and concomitantly enlarge their cell bodies, leading to bushy and/or ameboid morphologies8. During a change in CNS activity or health, microglia can become hyperproliferative, contributing to an increased number of microglial cells in an affected CNS area9. During neurovascular disease or injury, for example, microglia have been shown to migrate to sites of injury to “seal” damaged microvessels and to phagocytose tissue debris10,11. Further evidence for directed migration of microglia has been shown during ischemic stroke, in which microglia sense chemoattractant gradients and move toward ischemic tissue regions7. Analysis of multiple, different microglial parameters is necessary to accurately understand the response of and roles for these heterogeneous cells during specific pathogenic conditions.

CNS microglia communicate and function closely with the brain’s neurovascular unit (NVU), an anatomical and functional collection of neural and vascular cells—endothelial cells, pericytes, perivascular astrocytes, capillary basement membrane, and according to some reports, microglia—that interdependently promote development and maintenance of the blood–brain barrier (BBB)12,13. In the brain, a subset of microglia referred to as capillary-associated microglia (CAMs) have been defined14,15 and have been shown to influence neurovascular development and angiogenesis14. Specifically at regions of brain microvessels that lack astrocytic endfeet coverage, microglia directly interact with cellular components of the vessels16, such as forming cell–cell junctions with microvascular endothelial cells17,18 and through direct contact with pericytes and the shared pericyte-endothelial cell basement membrane, to support NVU communication16. During ischemic stroke and its accompanying BBB disruption, microglia promote vascular repair and remodeling and induce a cascade of signaling events involving release of inflammatory cytokines19,20 and the pro-angiogenic vascular endothelial growth factor19. These data suggest microglia states are altered during neurovascular injury.

Brain arteriovenous malformations (bAVM) are neurovascular abnormalities in which a healthy capillary network is supplanted by abnormally enlarged arteriovenous (AV) shunts that deliver blood directly from artery to vein21. In human patients, bAVMs have a 34% risk of rupture and account for 2% of all hemorrhagic strokes21. Data from human bAVM tissue samples and from animal models suggest that bAVMs are heterogeneous, in terms of causal disease initiation and progression12,22,23. To investigate CNS resident macrophage states during bAVM, we used an established mouse model in which endothelial Recombination signal binding protein for immunoglobulin kappa J region (Rbpj)-deficiency from birth leads to hallmarks of bAVM in frontal cortex and cerebellum within two weeks24,25. In endothelial Rbpj-deficient mice, bAVM pathologies manifest in a regionally and temporally regulated manner with severe perturbations to NVU components and functions, including endothelial cells, pericytes, their shared basement membrane, cerebellar neural cells, motor behavior, and BBB integrity22,24,25,26. Because of the loss of neurovascular capillary beds in bAVM, we hypothesized that CNS resident macrophage states, including changes to cellular, molecular, and functional properties, will be altered during pathogenesis of Rbpj-deficient bAVM.

Results

Expanded Iba1 expression corresponded to abnormal vasculature in Rbpj-mutant cortex and was observed regionally in Rbpj-mutant cerebellum, as compared to controls, at P14 and P21

To analyze CNS resident macrophage response during bAVM, we bred ligand-inducible Cdh5(PAC)-CreERT2, Rbpjflox/wt (control) and Cdh5(PAC)-CreERT2; Rbpjflox/flox (Rbpj-mutant) mice. Brain AV connections in heterozygous control mice showed capillary-like diameters and did not differ from Cdh5(PAC)-CreERT2; Rbpjwt/wt (wild-type) mice (Supplementary Fig. 1), consistent with similar findings for liver sinusoid diameter in these genetic cohorts27. To determine whether sex is a biological variable for AV connection diameter, we separated data into female and male datasets but did not observe differences among any cohort (Supplementary Fig. 1D–E). We administered Tamoxifen on postnatal day (P)1 and P2 to initiate Cre-ERT2-responsive deletion of Rbpj specifically from vascular endothelium—absence of endothelial Rbpj from P7 was previously reported22,24,25. To establish an operational method to identify microglia in brain tissue sections, we co-immunostained against a set of cell markers, including Iba1 (expressed by microglia and circulating macrophages; expression changes as microglia state changes), TMEM119 (expressed by microglia), and CD68 (expressed by microglia;). In P14 and P21 control and mutant tissue, most Iba1 + cells co-expressed the microglial marker TMEM119, as follows: P14 control cortex (91.89%) and cerebellum (88.39%); P14 mutant cortex (76.5%) and cerebellum (90.84%); P21 control cortex (92.37%) and cerebellum (86.5%); P21 mutant cortex (90.76%) and cerebellum (86.38%) (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 2). Comparing matched (age and brain region) control and mutant cohorts, we found a statistically significant difference between control and mutant cells in P14 cortex, suggesting that endothelial Rbpj deletion and vascular injury may recruit more Iba1 + macrophages to affected tissue regions. To assess the impact of endothelial Rbpj deletion on CNS resident macrophages, in the context of vascular abnormalities, we analyzed Iba1 expression, whose upregulation is widely reported as a state change in microglia following brain tissue injury6, on midsagittal sections through P14 and P21 brain tissue (Fig. 2A). Concurrently, endothelial cells were highlighted by membrane-localized (m)GFP, a CreERT2-responsive genetic marker expressed by Rosa26mT/mG28, an allele bred into control and Rbpj-mutant mice. Initial observations revealed increased mGFP + endothelial area at P14 and P21 (Fig. 2B-E), suggesting abnormal vasculature, consistent with previous findings24,26. Examination of Iba1 + expression indicated Iba1 + expansion in mutant cortical tissue, as compared to controls (Fig. 2B–E). While regions with expansive Iba1 expression did not exclusively overlap with areas exhibiting severe vascular anomalies, expanded Iba1 expression was exclusively observed in mutant mice with mGFP + abnormal vessels, suggesting a link between Rbpj-deficient vascular abnormalities and expansion of microglial Iba1 expression. Because we previously reported region-specific effects on brain tissue in our Rbpj-mutant mice24,25,26, we extended our analysis to the cerebellum. In cerebellum, we noted qualitative differences in Iba1 + area in different cerebellum regions, with expansion evident in Rbpj-mutant white matter and granular layers, but not molecular layers, as compared to controls, at P14 (Supplementary Fig. 3A–B′) and P21 (Supplementary Fig. 3C–D′). This pattern of Iba1 + expression in the cerebellum suggests region-specific CNS resident macrophage subpopulations may promote region-specific responses within the cerebellar microenvironment, following endothelial Rbpj deletion.

A subset of resident brain macrophages in early postnatal cortex co-expressed Iba1, TMEM119, and CD68. (A–B) In P14 cortex, immunostaining against Iba1 (red) and TMEM119 (green) showed the majority of Iba1 + cells co-express microglia marker TMEM119 in control and mutant tissue. (C–D) High magnification images showed co-localization of Iba1 (red) with microglia markers TMEM119 (green) and CD68 (white). (E) Quantification of the percentage of Iba1 + cells that co-express TMEM119. (F–G) In P21 cerebellum, the majority of Iba1 + cells co-expressed TMEM119 in control and mutant tissue. (H–I) High magnification images showed co-localization of Iba1, TMEM119, and CD68. (J) Quantification of the percentage of Iba1 + cells that co-express TMEM119. n = 4 for all cohorts.

Expanded Iba1 expression was visualized with abnormal vasculature in Rbpj-mutant cortex, as compared to controls, at P14 and P21. Co-labelling of mGFP + endothelium (green) and Iba1 + microglia (red) in (A) the cortex of control and mutant mice at (B–C) P14 and (D–E) P21 qualitatively showed enlarged and dense vessels situated within dense populations of Iba1 + cells.

Increased Iba1 expression, Iba1 + cell number, and Iba1 + cell proliferation was found in Rbpj-mutant cortex and was found regionally in Rbpj-mutant cerebellum, as compared to controls, at P14 and P21

We next quantified Iba1 + area in cortex and cerebellum tissue from P14 and P21 control and Rbpj-mutant mice. At both P14 and P21, we measured increased percentage of Iba1 + area per tissue area in Rbpj-mutant cortex (Fig. 3A–C,F) and cerebellum (Supplementary Fig. 3B–F′). Because sex as a biological variable has been reported to define select microglial states4,29, we analyzed Iba1 + expression area in separate datasets from P21 mice and found increased Iba1 + area in both females and males (Fig. 3F; Supplementary Fig. 3F). Expansion of Iba1 expression was accompanied by an increased number of Iba1 + cells in the cortex at P14 (Fig. 3D) and P21 (Fig. 3G, separated into female and male cohorts), and in the cerebellum at P21 (Supplementary Figure 3G–G′, combined, female, male cohorts). During analysis of the cerebellum, we noted differences in Iba1 expression in different cerebellum layers. At P14 and P21, we found increased Iba1 + expression area in cerebellar white matter and granular layers (Supplementary Fig. 4A–D,F–G), but not cerebellum molecular layers (Supplementary Fig. 4A,B,E,H), as compared to controls. We found increased Iba1 + cell number in the cerebellar white matter at P14 and P21 (Supplementary Fig. 4C′,F′) but not in the cerebellar granular and molecular layers at P14 or P21 (Supplementary Fig. 4D′,E′,G′,H′). To determine whether hyperproliferation contributes to increased cell number, we performed an EdU incorporation assay at P14 (EdU administered at P12, P13, P14) and P21 (EdU administered at P19, P20, P21). By P14 and P21, the percentage of Iba1 + ;Edu + cells (proliferative CNS resident macrophages) was increased in Rbpj-mutant cortex (P14, Fig. 3A′′′,B′′′,E and P21 Fig. 3H) and cerebellar white matter (Supplementary Fig. 4A′′,B′′,C′′’,F′′), compared to controls. No change was observed in cerebellar granular (Supplementary Fig. 4D′′,G′′) and molecular (Supplementary Fig. 4E′′,H′′) layers. To determine whether apoptotic cell death might contribute to altered Iba1 + number between control and Rbpj-mutant brain tissue, we counted Iba1 + ;TUNEL + cells. No evidence for altered Iba1 + cell death was found in Rbpj-mutant tissue at P14 or P21, in any brain region analyzed (cortex, Supplementary Fig. 5A–D; cerebellum Supplementary Fig. 5E–L). Together, these data suggest that hyperproliferation of Rbpj-mutant CNS resident macrophage leads to increased number of Iba1 + cells, which contributes to Iba1 + area expansion in Rbpj-mutant cortex and cerebellar white matter.

Microglia exhibited an increase in Iba1 expression, cell number, and proliferation at P14 and P21 in mutant cortex as compared to controls. Representative images of (A–A′′′) control P14 and (B–B′′′) mutant P14 are shown. Staining is represented with DAPI in blue for cell nuclei, Iba1 + cells in red, and Edu + cells in white. (A′′′, B′′′) Iba1 + ;Edu + cells, indicative of proliferative microglia, are circled in white. P14 analysis showed: (C) increased percentage of Iba1 + area (P = 0.0006, n = 9 for both control and mutant), (D) increased number of Iba1 + cells (P = 0.0029, n = 5 controls, n = 5 mutants), and (E) increased number of Iba1 + ;Edu + proliferative microglia (P = 0.0480, n = 4 controls, n = 3 mutants). (F) P21 analysis (two-way ANOVA) showed increased percentage of Iba1 + area, as analyzed by sex. Female control vs. Female mutant, P = 0.0002. Male control vs. Male mutant, P = 0.0016. Female control vs. Male control, P = 0.5354. Female mutant vs. Male mutant, P = 0.9481. Females, n = 7 controls and n = 6 mutants. Males, n = 5 controls and n = 4 mutants. (G) P21 analysis (two-way ANOVA) showed increased number of Iba1 + cells, as analyzed by sex. Female control vs. Female mutant, P = 0.0244. Male control vs. Male mutant, P = 0.0159. Female control vs. Male control, P > 0.9999. Female mutant vs. Male mutant, P = 0.9846. Females, n = 3 for controls and mutants. Males, n = 3 for controls and mutants. (H) increased number of Iba1 + ;;Edu + proliferative microglia (P = 0.0451, n = 4 controls and mutants). (I) RT-qPCR data demonstrated elevated Iba1 RNA expression in isolated P14 cortical microglia of mutants (P = 0.0260, n = 3 for both control and mutant) and (J–J′) increased Iba1 protein expression in the whole cortex (P = 0.0063, n = 3 for both control and mutant).

To quantify cellular Iba1 expression, we isolated CNS resident macrophages from cortex only, and from cerebellum only at P14, and we measured increased Iba1 expression, via RT-qPCR, in all cells from Rbpj-mutants, compared to controls (P14 cortex, Fig. 3I; P14 cerebellum, Supplementary Fig. 4I). Following on our Iba1 transcript data, we isolated cortical CNS resident macrophages from P14 brain tissue and found increased expression of Iba1 protein in mutant cortex (Fig. 3J–J′; Supplementary Fig. 4J–J′), as compared to controls.

Increased Iba1 + density was evident throughout Rbpj-mutant cortex at P14 and P21

To investigate CNS resident macrophage dynamics, we identified distinct areas of increased Iba1 + density, defined as at least a two-fold increase in the number of Iba1 + cells (refer to Methods) within brain tissue regions. We scored these density zones from 0 (low-Iba1 + density) to 3 (high-Iba1 + density) (Supplementary Fig. 6A–D). By P14 and P21, our observations revealed an increased number of high-Iba1 + density zones throughout Rbpj-mutant cortex, with varying degrees of severity, as compared to controls (P14, Fig. 4B–D; P21, Fig. 4E–G). This consistency over time suggests sustained or progressive changes in microglial behavior in the mutant cortex. While Iba1 + density in the cerebellum was not as consistent or pronounced as in the cortex, qualitative observations indicated its presence. This suggests a degree of variability in the formation of density zones between different brain regions. In cerebellum, most areas with high-Iba1 + density occurred within the white matter, with fewer instances of dense zones found in other cerebellar regions (refer to Supplementary Fig. 4B and Supplementary Fig. 5F).

High-Iba1 + density zones was observed in mutant mice compared to controls at P14 and P21, with increased cell number and proliferation within high-Iba1 + density zones. (A) Schematic depicts midsagittal cortical region used in analyses. Immunostaining against Iba1 in (B) control and (C) mutant showed high-Iba1 + density in mutant cortex at P14 and at P21, (E) control versus (F) mutant. Quantitative density score analysis for (D) P14 (P = 0.0001, n = 9 for control and mutant) and (G) P21 (P = 0.0039, n = 5 for control and mutant). Pairwise analyses were conducted for the (H) number of Iba1 + microglia in non-infiltrated versus infiltrated regions at both P14 (P = 0.0186) and P21 (P = 0.0074), and for the (I) percentage of proliferation at P14 (P = 0.0051, n = 4 for control and mutant) and P21 (P = 0.0452, n = 4 for control and mutant). Analysis for comparison of low-Iba1 + density zone and control samples is shown for (J) number of Iba1 + microglia at P14 (P = 0.6233, n = 4 for control and mutant) and P21 (P = 0.5610, n = 4 for control and mutant) as well as for the (K) percentage of proliferation at P14 (P = 0.2243, n = 4 for control and mutant) and P21 (P = 0.8576, n = 4 for control and mutant).

Upon comparing cortical high-Iba1 + density zones with adjacent low-Iba1 + density zones, we found distinct CNS resident macrophage populations. Pairwise comparisons from low- and high Iba1 + density zones from individual mutant cortices showed a range of approximately three- to six-fold increase in the number of Iba1 + cells, by P14 and P21 (Fig. 4H), thus underscoring the localized nature of altered CNS resident macrophage states within these zones. Analysis of Iba1 + cell proliferation within high and low-Iba1 + density zones revealed an increased percentage of Iba1 + ;EdU + cells within high-Iba1 + density zones (Fig. 4I). No changes were found in the percentage of TUNEL + ;Iba1 + cells in P14 and P21 high-Iba1 + density zones versus low-Iba1 + density zones in Rbpj-mutant cortex (Supplementary Fig. 6E–F). While we did not assess CNS resident macrophage migration directly, as contributing directly to the increased density within high-Iba1 + density zones, we did not find a decreased number of Iba1 + cells or an increased number of proliferating Iba1 + cells in the mutant low-Iba1 + density zones , as compared to control tissue, which would have suggested the nearby cells were recruited toward the high-Iba1 + density zones. These findings suggest that within select Rbpj-mutant tissue regions—defined as high-Iba1 + density zones—elevated Iba1 + cell proliferation promotes increased microglial density, without concomitant cell death.

We compared low-Iba1 + density zones from Rbpj-mutant cortex to control cortex and found no significant differences in the density of Iba1 + cells (Fig. 4J) or in the percentage of Iba1 + ;EdU + cells (Fig. 4K) at P14 or P21. It is likely that low-Iba1 + density zones within Rbpj-mutant cortex maintain a baseline level of CNS resident macrophages presence and activity, like that observed under normal physiological conditions in control cortex. This contrasts the heightened CNS resident macrophages presence in the high-Iba1 + density zones, thus underscoring the localized nature of response.

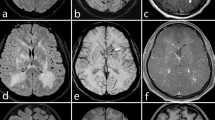

Increased density of Iba1 + /TMEM119 + /CD68 + microglia correlated with areas of increased vessel permeability in P14 Rbpj-mutant brain tissue

To determine whether microglia and/or non-CNS resident immune cells would preferentially associate with damaged vessels within bAVM tissue, we assessed extravasation of fluorescein-labelled circulating Dextran (4 kDa) and microglia density (Fig. 5). As expected, there was no evidence for Dextran leakage in control cortex or cerebellum, and Iba1 + and CD68(low) + cells were distributed throughout this tissue (Fig. 5B,D,G,I). However, in Rbpj-mutant cortex and cerebellum, a high density of Iba1 + and CD68(high) + cells were observed in swathes of tissue with Dextran extravasation (Fig. 5C,E,H,J). Increased density of Iba1 + ;CD68(high) + cells adjacent to sites of vessel leakage may result from extravasation of Iba1 + ;CD68(high) + non-CNS resident macrophages to those tissue regions, localized upregulation of immune cell markers in CNS resident or extravasated non-CNS resident immune cells, and/or localized proliferation of CNS or non-CNS resident immune cells.

Increased density of Iba1 + /CD68 + microglia was associated with areas of increased vascular permeability in P14 Rbpj-mutant brain tissue. (A) Schematic depicts midsagittal cortical region used in analyses. (B–E) Immunostaining against Iba1 (red) and CD68 (white) in control (B, D) and mutant (C, E) cortex at P14 demonstrated increased density of Iba1 + /CD68 + microglia in areas of increased vascular extravasation of 4 kDa fluorescein-conjugated Dextran (green). DAPI labeled cell nuclei (blue). (F) Schematic representation of the midsagittal cerebellum regions. (G–J) Immunostaining against Iba1 (red) and CD68 (white) in control (G, I) and mutant (H, J) cerebellum at P14 demonstrated increased density of Iba1 + /CD68 + microglia in areas of increased vascular extravasation of 4 kDa fluorescein-conjugated Dextran (green).

Iba1 + cells within high-Iba1 + density zones showed altered cell morphologies by P14 and P21 in Rbpj-mutant mice, as compared to controls

We next analyzed Iba1 + cell morphologies within infiltration zones, reasoning that CNS resident macrophages may may alter their cell shape state during Rbpj-bAVM. Cell tracings of high-magnification images revealed that P14 and P21 control Iba1 + cells displayed relatively small cell bodies and long, branching process, typical of a surveillant state (P14, Fig. 6A–A′; P21, Fig. 6E–E′). Within P14 and P21 Rbpj-mutant high-Iba1 + density zones, Iba1 + cells appeared bushy, with visibly enlarged cell bodies and comparatively shortened processes (P14, Fig. 6B′–B′′; P21, Fig. 6F–F′′), and some exhibited an ameboid morphology, entirely lacking processes and possessing larger cell bodies (P14, Fig. 6B′′′). Morphometric quantification revealed significantly increased cell body area of P14 and P21 cortical CNS resident macrophages in Rbpj-mutants (P14, Fig. 6C; P21, Fig. 6G), accompanied by decreased process length, as compared to controls (P14, Fig. 6D; P21, Fig. 6H). The morphological changes in CNS resident macrophages may be predictive of the functional state of these cells and suggest a persistent shift, over time, from a surveillant morphological state towards a higher-migratory state in Rbpj-mutant CNS resident macrophages. The persistence of these changes from P14 to P21 suggests a sustained alteration in morphological state in Rbpj-deficient mutants.

Iba1 + cells within cortical high-Iba + density zones showed altered cell morphologies by P14 and P21 in Rbpj-mutant mice, as compared to controls. (A–B) High magnification images of Iba1 + cells from P14 controls and mutants. (A′, B′–B′′′) Cell tracings of Iba1 + cells showed morphological changes in P14 mutant microglia. (E–F) High magnification images of Iba1 + cells from P21 controls and mutants. (E′, F′–F′′) Cell tracings of Iba1 + cells showed morphological changes in P21 mutant microglia. Quantification of cell body areas shown in (C) P14 (P = 0.0410) and (G) P21 (P = 0.0388); quantification of cell process length shown in (D) P14 (P < 0.0001) and (H) P21 (P = 0.0002). Black cells in images represent Iba1 + cells; in illustrations, cell bodies are grey, and processes are black. A sample size of n = 4 for both control and mutant groups was used.

Iba1 + cells showed increased cell body area in cerebellar white matter and granular layer, with reduced cellular processes in white matter of Rbpj-mutants by P14 and P21

We similarly assessed Iba1 + cell morphology in cerebellar white matter (Supplementary Fig. 7A–B′′), granular (Supplementary Fig. 7G–H′), and molecular layers (Supplementary Fig. 7M–N′). By P14 and P21, we found increased cell body area (P14, Supplementary Fig. 7B–B′′,C; P21, Supplementary Fig. 7E), coupled with decreased process length (P14, Supplementary Fig. 7B–B′′,D; P21, Supplementary Fig. 7F), in Rbpj-mutant cerebellar white matter, as compared to controls, suggesting a shift in CNS resident macrophage morphological state. By contrast, the granular layer showed increased cell body area (P14, Supplementary Fig. 7I; P21, Supplementary Fig. 7K), but no changes in process length (P14, Supplementary Fig. 7J; P21, Supplementary Fig. 7L), while the molecular layer showed no changes in cell body area (P14, Supplementary Fig. 7O; P21, Supplementary Fig. 7Q) or process length (P14, Supplementary Fig. 7P; P21, Supplementary Fig. 7R). These distinct morphological patterns within the Rbpj-mutant cerebellum, over time, suggest sustained, region-specific variations in CNS resident macrophage state, which may impart different functional consequences among cerebellar layers in Rbpj-mutant brain tissue.

CNS resident macrophages from Rbpj-mutant cortex and cerebellum displayed molecular phenotypes along a spectrum of classical pro-, intermediate-, and anti-inflammatory markers

We used flow cytometry to uncover molecular profiles for Rbpj-mutant CNS resident macrophages isolated from whole cortex and whole cerebellum tissues. We immunolabelled against CD45 and CD11b to identify CD45high;CD11b + cell populations in controls and mutants (Fig. 7A,B). Quantitative analysis showed an increased percentage of CD45int/high;CD11b + cells (Fig. 7E) and decreased percentage of CD45low;CD11b + cells (Fig. 7F) in P14 Rbpj-mutant cortex, as compared to controls, indicating altered CNS resident macrophage molecular state in Rbpj-mutants. Using these CD45high;CD11b + cohorts, we further immunostained against CD86 (classically pro-inflammatory) and CD206 (classically anti-inflammatory) (Fig. 7C,D) to assess relative expression of CD86 (high/low) and CD206 (high/low) among CD45int/high;CD11b + cells. Quantification showed significant increases in CD206-;CD86 + , CD206 + ;CD86-, and CD206 + ;CD86 + CNS resident macrophage states (Fig. 7G). Notably, the increase in CD45high;CD11b + cells expressing CD86 was more pronounced than that observed in other states, suggesting that CNS resident macrophages from Rbpj-mutant cortex may be skewed toward a CD45high;CD11b + ;CD86 (classically pro-inflammatory) state and that non-CNS resident macrophages from peripheral circulation may have infiltrated brain parenchyma via extravasation from leaky brain vessels. The increased proportion of CNS resident macrophages in the intermediate state (CD45high;CD11b + ;CD206 + ;CD86 +) suggests a complex and dynamic change in the Rbpj-mutant brain tissue microenvironment, in which non-CNS macrophages infiltrate bAVM tissue and CNS resident macrophages enter a state of transition or a response to diverse signaling cues.

Flow cytometry analysis identified distinct resident macrophage populations in control and mutant mouse cortex at P14. (A–B) Percentages of CD45int/high;CD11b + and CD45low;CD11b + cells isolated from P14 control and mutant whole cortex tissue. (C–D) Distribution of CD45int/high;CD11b + cells, as relates to expression of CD206 and CD86. (E) Rbpj-mutant cortex showed increased percentage of CD45int/high;CD11b + cells (P = 0.0018) and (F) decreased percentage of CD45low;CD11b + cells (P = 0.0002), as compared to controls. (G) Cortex microglia from mutant and control brain fell into distinct subpopulations, based on CD86 and CD206 expression: CD86-;CD206 + (P = 0.0433), CD86 + ;CD206 + (P = 0.0350), and CD86 + ;CD206- (P = 0.0051). A sample size of n = 3 for both control and mutant groups was used, with each analysis encompassing 10,000 events per sample.

Flow cytometry analysis of the cerebellum revealed an increased percentage of CD45int/high;CD11b + cells (Supplementary Fig. 8A–D,E) and decreased percentage of CD45low;CD11b + cells (Supplementary Fig. 8F) in P14 Rbpj-mutant cerebellum, as compared to controls. This finding underscores an altered CNS resident macrophage molecular state in cerebellum, consistent with data from cortex. However, in the cerebellum there were no changes in CD206 or CD86 expression levels in the CD45int/high;CD11b + cells, as compared to controls (Supplementary Fig. 8G). These data suggest a distinct molecular profile for CNS resident macrophages in the cerebellum, as compared to their cortical counterparts.

Gene expression changes suggested differential CNS resident macrophages states in cortex and cerebellum by P14 in Rbpj-mutant brain

To uncover a more comprehensive molecular profile for cortical and cerebellar CNS resident macrophages, we selected a panel of factors described in altered states for gene expression analysis using RT-qPCR. Candidate factors were selected, based on their roles in cell signaling events that promote or inhibit tissue inflammation or that are involved in antigen recognition, previously described as immunovigilance. Compared to controls, CNS resident macrophages isolated from P14 Rbpj-mutant cortex showed increased expression of the following: CD14, a gene generally indicative of a robust immunogenic response (Fig. 8A, dark gray bar); TNFα (Tumor Necrosis Factor α), CD32 (encoding an Fc gamma receptor), and IL-1β, known mediators of inflammatory responses in the CNS, with CD32 expression exhibiting more than a fivefold increase and IL-1β over a twofold increase in expression in Rbpj-mutants, compared to controls (Fig. 8A, white bars); and Arg1 (Arginase 1), CD163 (encoding a scavenger receptor), and Tgfβ (Transforming growth factor β), mediators of anti-inflammatory and tissue-repair processes, with Arg1 expression greater than threefold in mutants (Fig. 8A, light gray bars). Decreased expression of IL-10, by almost fourfold in Rbpj-mutants (Fig. 8A), suggests transition toward an inflammatory response state, as increased IL-10 expression has been shown to inhibit inflammatory response30. Collectively, these results suggest complex regulation of CNS resident macrophages in the cortex. Our data indicate that resident CNS macrophages in Rbpj-mutant brain tissue predominantly express genes encoding inflammatory-response signaling factors, which may have significant implications for cortical function and pathology in the context of Rbpj-deficient bAVM.

Gene expression changes suggested differential CNS resident macrophage states, suggestive of functional abnormalities, in cortex and cerebellum from P14 Rbpj-mutant brain, as compared to controls. (A) Altered transcript expression in mutant cortex CNS resident macrophages, normalized to control, and categorized by gene product functional roles. CNS resident macrophages from Rbpj-mutant cortex showed abnormal expression of inflammatory response mediators, including Tnfα (P = 0.0285), CD32 (P = 0.0108), IL-1β (P = 0.0014); of anti-inflammatory/tissue repair factors, including Arg1 (P = 0.0475), IL-10 (P = 0.0130), CD163 (P = 0.0374), Tgfβ (P = 0.0080). Mutant CNS resident macrophages showed increased expression of a general immunogenic response factor CD14 (P = 0.0221). (B) Altered transcript expression in mutant cerebellum CNS resident macrophages, normalized to control. CNS resident macrophages from Rbpj-mutant cerebellum showed abnormally expressed Stat1 (P = 0.0469), H2D1 (P = 0.0105), H2AB1 (P = 0.0176), Clec4e (P = 0.0110), CD32 (P = 0.3290), IL-10 (P = 0.0447). (C) Altered expression of metabolic genes in mutant cortex CNS resident macrophages, normalized to control. CNS resident macrophages from Rbpj-mutant cortex showed increased expression of Snat1 (P = 0.0046) and Glut3 (i = 0.0469), and no change in expression of Glut5 (P = 0.3076). All transcripts were assessed with a sample size of n = 3.

For gene expression analysis in CNS resident macrophages isolated from cerebellum, we selected genes previously shown to be upregulated and functionally relevant specifically in cerebellar microglia31. Compared to controls, CNS resident macrophages isolated from P14 Rbpj-mutant cerebellum showed no change in CD32 (inflammatory mediator described above) and showed decreased expression of H2D1 (encodes class I MHC) (Fig. 8B). CNS resident macrophages from Rbpj-mutant cerebellum also showed increased expression of the following: Stat1, integral to immunoregulation; H2AB1, encodes class II major histocompatibility complex (MHC) in antigen recognition; Clec4e, a key molecule in pathogen recognition; and IL-10 (Fig. 8B). Flow cytometry data confirmed no altered expression of CD86 and CD206 (Supplementary Fig. 8). Collectively, this pattern of expression suggests a distinctive profile for cerebellar CNS resident macrophages in Rbpj-mutant bAVM, when compared to their counterparts in Rbpj-mutant cortex. This profile suggests a state of immunovigilance – preparation for antigen recognition during an immunogenic response31.

Cortical CNS resident macrophages showed gene expression changes consistent with metabolic dysfunction by P14 in Rbpj-mutant brain tissue

To begin identifying changes in CNS resident macrophage function during Rbpj-deficient bAVM pathogenesis, we analyzed expression of molecules critical for regulating metabolic needs of the brain and indicators of mitochondrial and cellular health. RT-qPCR analysis for CNS resident macrophages isolated from P14 cortex revealed increased expression of Snat1 (encodes glutamine transporter primarily metabolized in mitochondria) and Glut3 (encodes glucose transporter broadly expressed by neural cells) (Fig. 8C). These findings suggest metabolic dysfunction in the Rbpj-mutant cortex, perhaps associated with an elevated inflammatory response during Rbpj-deficient bAVM. No change was seen in expression of Glut5 (fructose transporter specific to microglial cells) (Fig. 8C), suggesting a pathology-specific metabolic response.

Discussion

Our findings demonstrate that during Rbpj-deficient bAVM, CNS resident macrophages display altered cell biological, molecular, and functional states, in a regionally regulated manner. Increased Iba1 expression serves as one indicator of altered cell state in neuro-related disorders6. In Rbpj-mutant cortex and cerebellum, we observed expanded areas of Iba1 expression and increased Iba1 + cell number, states that were not dependent on sex of the mice, and increased cell body areas of Iba1 + cells in tissue sections and increased cellular expression of Iba1 transcripts and protein in isolated CNS resident macrophages—these data provided initial evidence for changes to CNS resident macrophages in the context of Rbpj-deficient bAVM and align with characteristics of responses identified in other neurovascular and neurodegenerative diseases6,32. While sex has been reported as a biological variable regulating microglia migration and Iba1 + cell density in adult mouse cortex29,33, our analyses included data from early postnatal mice. These P14 and P21 mice have not been exposed to adult-level sex hormones, which could contribute to sex differences among microglia states. Among different brain regions, the patterns of state change vary—for example, the cortex and cerebellar white matter showed cell hypertrophy and hyperproliferation related to Iba1 expansion, while the cerebellar granular layer showed hypertrophy and Iba1 expansion independent of hyperproliferation. These findings inform on the responses of CNS resident macrophages during bAVM, and they underscore the need to study various aspects—molecular, cell biological, and metabolic, functional—of such responses.

Our results demonstrate that in the Rbpj-mutant cortex and in cerebellar white matter and granular layers (but not in cerebellar molecular layers), Iba1 + cells showed cell body hypertrophy. In Rbpj-mutant cortex and cerebellar white matter (but not in granular or molecular layers), Iba1 + cells showed process retraction. These data are consistent with cellular transition in state and suggest brain region-specific CNS resident macrophage responses. Indeed, in healthy brain tissue, CNS resident macrophages exhibit remarkable heterogeneity and have diverse molecular and cellular properties across different brain regions31,34. CNS resident macrophage cell density varies significantly, with a higher concentration found in the cortex compared to the cerebellum. Within the cerebellum, white matter has the highest density of CNS resident macrophage, followed by the granular layer, and finally, the molecular layer with the lowest density31,34. In healthy cerebellum, Iba1 + cells are less ramified and more motile, compared to those in the cortex, likely attributable to their sparser distribution necessitating increased mobility for effective surveillance of cerebellar parenchyma35. Our observations of altered cell morphologies align with these findings, identifying the densest CNS resident macrophage population in the cerebellar white matter, followed by the granular layer, then the molecular layer.

We found dense clusters of Iba1 + cells throughout Rbpj-mutant brain, but with prominently high-Iba1 + density in the cortex. Our data suggest that increased cellular density within high-Iba1 + density zones likely results from a combination of increased Iba1 + cell proliferation and infiltration by non-resident, peripherally derived macrophages extravasating from compromised cerebrovascular structures into the brain parenchyma. Further, Iba1 + cell density in Rbpj-mutant low-Iba1 + density zones was comparable to cell density in control tissue. Thus, despite Rbpj-mutant cellular changes to more rounded, migratory-typical morphologies, we cannot determine from our current experimental data whether migration of Iba1 + cells from low-Iba1 + density zones into high-Iba1 + density zones contributes significantly to the increased Iba1 + cell population within high-Iba1 + density zones. Interestingly, high-Iba1 + density zones were not necessarily located adjacent to the most severe vascular abnormalities in Rbpj-mutant brain tissue; however, Iba1 + ;TMEM119 + ;CD68 + microglia showed greater cell density in areas of Dextran extravasation, suggesting infiltration of non-CNS resident macrophages into brain parenchyma and perhaps localized microglial response to increased vessel permeability. As our bAVM model develops abnormal vasculature throughout the brain, CNS and non-CNS resident macrophages may populate areas with the most vascular and neural tissue damage. These observations are consistent with human bAVM studies, where clustering of inflammatory cells, referred to as “infiltration,” has been documented36,37 and with other mouse models of bAVM, in which high-Iba1 + density patterns have been described38. While the mechanistic drivers of CNS and non-CNS resident macrophage infiltration remain unknown, one hypothesis posits that the NVU releases purinergic mediators, such as ATP and ADP, which recruit CNS resident macrophages in response to vascular anomalies18, hinting at a potential mechanism for cellular infiltration to oppose inflammation-induced tissue damage.

CNS resident macrophages, traditionally described along within a spectrum from pro-inflammatory/neurotoxic to anti-inflammatory/neuroprotective, perform diverse roles in CNS health and disease5. Our flow cytometry analyses, using classically recognized factors – CD86 and CD206—involved in immunogenic responses, revealed significant expression of both markers in the cortex, but not in the cerebellum. This dual expression within the cortical CNS resident macrophage population prompted further examination to determine the predominant molecular profile state in the cortex. While we found increased expression of both pro- and anti-inflammatory genes, we noted a significant decrease in IL-10, which suggests inhibition of transition toward an anti-inflammatory response30. These data suggest CNS and non-CNS resident macrophages in the Rbpj-mutant cortex are shifted toward a classically pro-inflammatory immunogenic response. Combined with cortical data, our findings demonstrate region-specific resident macrophage state changes in the context of endothelial Rbpj-mediated bAVM.

In the cerebellum, we explored an alternative immuno-related state of “immunovigilance,” characterized by expression of pathogen recognition transcripts and heightened immune responsiveness35. Our analyses showed gene expression data consistent with immunovigilant CNS resident macrophages in the Rbpj-mutant cerebellum. Despite our flow cytometry data showing no change in cerebellar CD86 expression, we observed significant increases in Stat1 and H2AB19 expression, suggesting antigen/pathogen recognition39 and thus primarily immunovigilant roles for cerebellar CNS resident macrophages.

When pathologically activated, the functional roles for CNS and non-CNS resident macrophages are perturbed, impacting cellular metabolic demand. Metabolic reprogramming has been identified as a pivotal component of microglial state transition, in which these cells exhibit a shift towards glycolysis for energy production, increasing glucose uptake, lactate production, and IL-1β secretion39,40,41,42. Our molecular data revealed increased IL-1β expression in cortical CNS resident macrophage from Rbpj-mutants, suggesting a metabolic shift and enhanced glycolysis. This adaptation is (1) particularly critical in hypoxic conditions to promote cell survival39 and (2) suggestive of an immunogenic response, as such cells rely predominantly more on glucose consumption to meet metabolic demand39,40,42. Our experiments also showed increased of expression of Snat1, which encodes a microglial-specific glutamine transporter and is required for glutamine metabolism43. Consistent with our data, in the human neurodevelopmental disease Rett syndrome, SNAT1 dysregulation leads to impaired metabolic function in microglia43. Our data showed increased expression of Glut3 in Rbpj-mutant CNS resident macrophages, supporting the idea of altered cell metabolism in Rbpj-deficient bAVM. Glut3, a glucose transporter expressed by microglia, plays a role in adapting to altered brain metabolism, as its increased expression in activated microglia has been shown to serve as a protective mechanism against cell damage44. Inflammatory signals can further modulate Glut3 expression, consistent with our observations of increased Glut3 expression in mutant cortical CNS resident macrophages. By contrast, Rbpj-mutant cortical cells showed no change in Glut5 expression – Glut5 encodes a fructose transporter predominantly found in microglia and does not respond to ischemic or hypoxic conditions45, such as those imposed by bAVM. These findings underscore a complex reprogramming of cellular metabolism in CNS resident macrophages, leading to cellular dysfunction and likely to effects on surrounding neural tissue.

An intriguing consideration is whether perturbations in CNS and/or non-CNS resident macrophages actively participate in bAVM pathogenesis and exacerbate the neurovascular disease. Given the tightly regulated and coordinated communication within the NVU, effects on one cell type have been shown to impart consequences to others, particularly in pathological conditions such as neurovascular disease25,26. Identifying consequences to CNS and/or non-CNS resident macrophages during bAVM may inform on novel targetable factors and inspire investigations into whether targeting specific cellular properties could offer therapeutic benefit to bAVM patients, potentially preserving brain tissue and alleviating symptoms.

Methods

Adherence to experimental guidelines and mouse genetics

All experiments, including methods for anesthesia, euthanasia, and assessment of humane endpoint, were performed in accordance with (1) Ohio University’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) protocol number 16-H-024; (2) Animal Welfare Assurance Number, A3610-01, on file with the National Institutes of Health’s Office of Laboratory Animal Welfare; (3) Ohio University United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) license 31-R-0082; (4) USDA Animal Welfare Act Regulations and the Public Health Service Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Animals; (5) accreditation by the Association for the Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International (AAALAC). Experimental protocols involving animal subjects (mice) were approved by the Ohio University IACUC, under protocol 16-H-024. Experiments were performed in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines.

Mouse lines used were: Cdh5(PAC)-CreERT246, provided by Taconic Biosciences; Rbpjflox 47, provided by Tasuku Honjo (Kyoto University); and Rosa26mT/mG28, provided by Jackson Laboratory [GT(Rosa)26SorTM4(ACTB–tdTomato–EGFP)Luo: JAX stock #007576]. At postnatal day (P) 1 and P2, 100 μg of Tamoxifen (Sigma) in 50 μL of peanut oil (Planters) was injected intragastrically, as previously described24. PCR based genotyping was performed, as previously described24 on Bioer GenPro Thermal Cycler, except Rosa26mT/mG genotyping was performed by tail biopsy tissue fluorescence, using a Nikon NiU microscope.

Tissue harvest and processing

Brain tissue was harvested following intracardial perfusion and simultaneous euthanasia by exsanguination. Mice were perfused with 1% paraformaldehyde (PFA). For tissue sections, brains were hemisected, cryopreserved in 30% sucrose, and stored at − 80 °C. Mid-sagittal cryosections, 10–12 μm thick, were collected with a CM-1350 cryostat (Leica) and stored at − 80 °C. For vascular permeability assay, Fluorescein-conjugated 3000 molecular weight (MW) dextran (Thermofisher) and heparin (5 units per 10 g body weight, Alfa Aesar) were injected via inferior vena cava and brain tissue was harvested following transcardial perfusion with 1X PBS. Brains were hemisected, fixed in 4% PFA overnight, embedded in optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound, and stored at − 80 °C. Mid-sagittal cryosections 20 μm thick were collected via cryostat in 80 μm increments and stored at − 80 °C. For whole cortex preparation, a 2–3 mm thick slice of frontal cortex was removed with a scalpel.

Immunostaining, Edu incorporation, TUNEL and fluorescent imaging

Endothelial cells were genetically labeled with mGFP. Immunostaining against Iba1 + was performed with a 2% PFA fixation at room temperature (RT) for 10 min. Followed by 3 × PBS washes at RT. Cryosection slides were then blocked with 5% donkey serum and 0.1% Triton-X in 1X PBS. Combinations of primary antibodies Rabbit anti-Iba1 (Wako cat# 019–19741, 1:500), Rat anti-CD68 (Thermofisher cat# 14-0681-80, 1:300), and mouse anti-TMEM119 (Cell Signaling, cat # 98778, 1:100) were diluted in block, and slides were incubated at 4 degrees overnight in a humidity chamber. Post primary incubation, slides were washed with PBS-T (PBS + 0.1%Triton-X). Secondary antibodies were AlexaFluor®647 Donkey Anti-Rabbit (Jackson ImmunoResearch), AlexaFluor®647 Donkey Anti-Rat (Jackson ImmunoResearch), Alexa488® Donkey Anti-Rabbit (Jackson ImmunoResearch), Cy3 Donkey Anti-Mouse (Jackson ImmunoResearch), or Cy3 Donkey Anti-Rabbit (Jackson ImmunoResearch), each diluted 1:500 in block. Slides were incubated in humidity chamber for 2 h at RT. Slides were washed in PBS-T, then in PBS, followed by 3 min in 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) for nuclei labeling. Click-iT TUNEL Alexa Fluor 647 Imaging Kit (Invitrogen) was used following manufacturer’s instructions to assess apoptotic cells. Click-iT EdU AlexaFluor 647 Imaging Kit (Invitrogen) was used to test proliferation. EdU incorporation assay was performed by injecting mice intraperitoneally with 10 μg/gram of body weight with EdU at P8–10 or P12–14 or P19-21. On the day of harvest (P10 or P14 or P21), tissue was harvested 2 h post-injection. Detection of EdU used Click-iT™ Plus chemistry, with AlexaFluor® 647 component following manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen). This step was performed after secondary antibody but before DAPI application. Then slides were mounted with ProLong Gold™ (Invitrogen) and imaged using Nikon NiU microscope and NIS Elements Software.

Delineating high-Iba1 + density and low-Iba1 + density zones

High-Iba1 + density zones were defined as regions with Iba1 + cell density at least twice that observed in adjacent low-Iba1 + density zones. This definition was based on quantitative measurements of microglial density, ensuring accurate delineation between high and low-Iba1 + density regions. Once these zones were identified, we adopted a scoring system ranging from 0 (low-Iba1 + density) to 3 (high-Iba1 + density) to categorize the degree of density. This scoring was based on a set of criteria, including the extent of area covered by the density of microglial cells, and the degree of deviation from typical microglial density observed in control and low-Iba1 + density zone in mutant brain tissue.

Morphology analysis

To select cells, a grid was overlaid on the brain tissue image, and randomized number generator identified a grid point for cell selection and morphology analysis. For cell body area measurements, eight cells were measured; for dendrite measurements, five cells were selected and 1–3 processes per cell were measured. The researcher was not blinded to genotype information; however, the analyses were repeated, with consistent results, 6 months apart.

Cell isolation

Single cell isolation of microglia was achieved as described48 with minimal modifications. Mouse brains were harvested by rapid decapitation at P14 and P21. Brain stem and the olfactory bulbs were dissected away. The brains were dissected to pool 3–4 mouse cortices and cerebellum separately. The tissues were kept on ice in sterile 1 × DPBS and mechanically digested with a scalpel and 5 ml syringe then passed through a 70 µm cell strainer (Thermo Scientific). A discontinuous Percoll gradient was utilized by diluting GE Percoll (Cytiva) into an 100% stock isotonic Percoll (SIP) at a 9:1 ratio with 10 × PBS48. Discontinuous gradient was layered, from bottom to top, with 70% SIP with resuspended cells, 50% SIP, 35% SIP and DPBS (0% SIP) as described48. All centrifugations, except for Percoll gradient centrifugation, were performed at 600 g for 6 min at RT and Percoll gradients were centrifuged at 2000 g for 20 min at RT. Following Percoll gradient centrifugation, microglia were present and visible as a band of cells between 5.5 and 7 ml and were collected48 for RNA and protein extraction.

RNA extraction and RT-qPCR

RNA extraction from isolated microglia was performed with a PureLink RNA Mini Kit (Thermo Fischer Scientific) under sterile conditions, in an RNA-dedicated space and according to manufacturer instructions. RNA was quantified with Nanodrop. RT-qPCR was performed with qScript One-Step SYBR Green RT-qPCR (Quantabio) on a CFX Connect Real-Time PCR Detection System (BioRad), using CFX Maestro 2.0 Software for Windows PC (BioRad). Quantification was performed with a comparative CT method on Microsoft Excel49. All mouse primers used are detailed in Supplementary Table 1. Pilot microglia isolations were checked for contamination with RT-qPCR via Cq value comparison (Supplementary Table 2).

Protein extraction and Western blotting

Isolated microglial protein was extracted in 1X RIPA buffer. Protein concentration was estimated using Precision Red (Cytoskeleton, Inc.) and NanoDrop One spectrophotometer. Proteins were separated using an 8% polyacrylamide separating/resolving gel, 4% stacking gel, and electrophoresis. Protein was transferred to PVDF membrane, and membrane was blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin in tris-buffered saline with Tween-20, before incubating with primary antibodies. Primary antibody dilutions: rabbit anti-Gapdh (1:1,000) (Cell Signaling Technologies); rabbit anti-Iba1 (Wako cat# 019–19,741) (1:1,000). HRP-conjugated secondary antibody anti-rabbit (1:1,000) (Cell Signaling Technologies). Chemiluminescent substrate was applied to the membrane, and bands were detected and quantified with BioRad ChemiDoc XRS + and ImageLab software.

Flow cytometry

Single cell suspensions for cortex and cerebellum from P14 mice (see above) were incubated with PE-Cy7 Rat Anti-Mouse CD45, FITC Rat Anti-Mouse CD11b, APC Rat Anti-Mouse CD86 and PE Rat Anti-Mouse CD206 for 30 min at RT. All antibodies for flow cytometry were acquired from BD Pharmingen. Aria Flow Cytometer was used to collect the necessary data. Prior to data collection the flow cytometer was calibrated with the following controls: CD45low/INT cells only, CD11b + cells only, CD86 + cells only, CD208 + cells only and unstained cells as well as FMO (fluorescence minus one) controls: FMO for CD45 = stain with CD11b, CD86, CD206; FMO for CD11b = stain with CD45, CD86, CD206; FMO for CD86 = stain with CD45, CD11b, CD206; FMO for CD206 = stain with CD45, CD11b, CD86.

Data analysis

Adobe Photoshop (Creative Cloud) and FIJI (National Institutes of Health) were utilized for cell counting and morphology analyses. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism and Microsoft Excel. Unpaired Student’s t-tests with Welch’s correction and Paired t-tests were used to compare values between control and mutant mice. P-values < 0.05 were considered significant, as follows: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001, ns = not significant.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in a OneDrive repository, https://catmailohio-my.sharepoint.com/:f:/r/personal/nielsenc_ohio_edu/Documents/Microglia%20manuscript_Nakisli/Nakisli%20Microglia_bAVM%20Data%20Availability?csf=1&web=1&e=zX4zsu.

References

Cherry, J. D., Olschowka, J. A. & O’Banion, M. K. Neuroinflammation and M2 microglia: the good, the bad, and the inflamed. J. Neuroinflamm. 11, 98 (2014).

Zhou, T. et al. Microglia polarization with M1/M2 phenotype changes in rd1 mouse model of retinal degeneration. Front. Neuroanat. 11, 77 (2017).

Bachiller, S. et al. Microglia in neurological diseases: A road map to brain-disease dependent-inflammatory response. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 12, 488 (2018).

Paolicelli, R. C. et al. Microglia states and nomenclature: A field at its crossroads. Neuron 110, 3458–3483 (2022).

Guo, S., Wang, H. & Yin, Y. Microglia polarization from M1 to M2 in neurodegenerative diseases. Front. Aging Neurosci. 14, 815347 (2022).

Jurga, A. M., Paleczna, M. & Kuter, K. Z. Overview of general and discriminating markers of differential microglia phenotypes. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 14, 198 (2020).

Patel, A. R., Ritzel, R., McCullough, L. D. & Liu, F. Microglia and ischemic stroke: a double-edged sword. Int. J. Physiol. Pathophysiol. Pharmacol. 5, 73–90 (2013).

Ziebell, J. M., Adelson, P. D. & Lifshitz, J. Microglia: Dismantling and rebuilding circuits after acute neurological injury. Metab. Brain Dis. 30, 393–400 (2015).

Pepe, G. et al. Selective proliferative response of microglia to alternative polarization signals. J. Neuroinflamm. 14, 236 (2017).

Grossman, R. et al. Juxtavascular microglia migrate along brain microvessels following activation during early postnatal development. Glia 37, 229–240 (2002).

Carbonell, W. S., Murase, S.-I., Horwitz, A. F. & Mandell, J. W. Migration of Perilesional Microglia after Focal Brain Injury and Modulation by CC Chemokine Receptor 5: An In Situ Time-Lapse Confocal Imaging Study. J. Neurosci. 25, 7040–7047 (2005).

Adhicary, S., Nakisli, S., Fanelli, K. & Nielsen, C. M. Neurovascular Development. In Reference Module in Biomedical Sciences B9780128188729002000 (Elsevier, 2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-818872-9.00106-0.

Krithika, S. & Sumi, S. Neurovascular inflammation in the pathogenesis of brain arteriovenous malformations. J. Cell. Physiol. 236, 4841–4856 (2021).

Zhao, X., Eyo, U. B., Murugan, M. & Wu, L. Microglial interactions with the neurovascular system in physiology and pathology. Dev. Neurobiol. 78, 604–617 (2018).

Bisht, K. et al. Capillary-associated microglia regulate vascular structure and function through PANX1-P2RY12 coupling in mice. Nat. Commun. 12, 5289 (2021).

Morris, G. P. et al. Microglia directly associate with pericytes in the central nervous system. Glia 71, 1847–1869 (2023).

Haruwaka, K. et al. Dual microglia effects on blood brain barrier permeability induced by systemic inflammation. Nat. Commun. 10, 5816 (2019).

Császár, E. et al. Microglia modulate blood flow, neurovascular coupling, and hypoperfusion via purinergic actions. J. Exp. Med. 219, e20211071 (2022).

Qin, C. et al. Dual functions of microglia in ischemic stroke. Neurosci. Bull. 35, 921–933 (2019).

Jolivel, V. et al. Perivascular microglia promote blood vessel disintegration in the ischemic penumbra. Acta Neuropathol. (Berl.) 129, 279–295 (2015).

Nakisli, S., Lagares, A., Nielsen, C. M. & Cuervo, H. Pericytes and vascular smooth muscle cells in central nervous system arteriovenous malformations. Front. Physiol. 14, 1210563 (2023).

Adhicary, S. et al. Rbpj deficiency disrupts vascular remodeling via abnormal apelin and Cdc42 (cell division cycle 42) activity in brain arteriovenous malformation. Stroke https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.122.041853 (2023).

Winkler, E. A. et al. A single-cell atlas of the normal and malformed human brain vasculature. Science 375, eabi7377 (2022).

Nielsen, C. M. et al. Deletion of Rbpj from postnatal endothelium leads to abnormal arteriovenous shunting in mice. Development 141, 3782–3792 (2014).

Chapman, A. D. et al. Endothelial Rbpj is required for cerebellar morphogenesis and motor control in the early postnatal mouse Brain. Cerebellum https://doi.org/10.1007/s12311-022-01429-w (2022).

Selhorst, S., Nakisli, S., Kandalai, S., Adhicary, S. & Nielsen, C. M. Pathological pericyte expansion and impaired endothelial cell-pericyte communication in endothelial Rbpj deficient brain arteriovenous malformation. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 16, 974033 (2022).

Cuervo, H. et al. Endothelial notch signaling is essential to prevent hepatic vascular malformations in mice: Notch Signaling Prevents Hepatic Vascular Malformations in Mice. Hepatology 64, 1302–1316 (2016).

Muzumdar, M. D., Tasic, B., Miyamichi, K., Li, L. & Luo, L. A global double-fluorescent Cre reporter mouse. Genesis 45, 593–605 (2007).

Boghozian, R., Sharma, S., Narayana, K., Cheema, M. & Brown, C. E. Sex and interferon gamma signaling regulate microglia migration in the adult mouse cortex in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 120, e2302892120 (2023).

Laffer, B. et al. Loss of IL-10 promotes differentiation of microglia to a M1 phenotype. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 13, 430 (2019).

Tan, Y.-L., Yuan, Y. & Tian, L. Microglial regional heterogeneity and its role in the brain. Mol. Psychiatry 25, 351–367 (2020).

Kenkhuis, B. et al. Co-expression patterns of microglia markers Iba1, TMEM119 and P2RY12 in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 167, 105684 (2022).

Han, J., Fan, Y., Zhou, K., Blomgren, K. & Harris, R. A. Uncovering sex differences of rodent microglia. J. Neuroinflammation 18, 74 (2021).

Uriarte Huarte, O., Richart, L., Mittelbronn, M. & Michelucci, A. Microglia in health and disease: The strength to be diverse and reactive. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 15, 660523 (2021).

Stoessel, M. B. & Majewska, A. K. Little cells of the little brain: Microglia in cerebellar development and function. Trends Neurosci. 44, 564–578 (2021).

Nakamura, S. et al. Gene therapy for a mouse model of glucose transporter-1 deficiency syndrome. Mol. Genet. Metab. Rep. 10, 67–74 (2017).

Chen, Y. et al. Evidence of inflammatory cell involvement in brain arteriovenous malformations. Neurosurgery 62, 1340–1350 (2008).

Zhang, R. et al. Persistent infiltration and pro-inflammatory differentiation of monocytes cause unresolved inflammation in brain arteriovenous malformation. Angiogenesis 19, 451–461 (2016).

Orihuela, R., McPherson, C. A. & Harry, G. J. Microglial M1/M2 polarization and metabolic states. Br. J. Pharmacol. 173, 649–665 (2016).

Yang, S. et al. Microglia reprogram metabolic profiles for phenotype and function changes in central nervous system. Neurobiol. Dis. 152, 105290 (2021).

Krawczyk, C. M. et al. Toll-like receptor–induced changes in glycolytic metabolism regulate dendritic cell activation. Blood 115, 4742–4749 (2010).

Rodríguez-Prados, J.-C. et al. Substrate fate in activated macrophages: A comparison between innate, classic, and alternative activation. J. Immunol. 185, 605–614 (2010).

Jin, L.-W. et al. Dysregulation of glutamine transporter SNAT1 in Rett syndrome microglia: A mechanism for mitochondrial dysfunction and neurotoxicity. J. Neurosci. 35, 2516–2529 (2015).

Gutiérrez Aguilar, G. F. et al. Resveratrol prevents GLUT3 up-regulation induced by middle cerebral artery occlusion. Brain Sci. 10, 651 (2020).

Douard, V. & Ferraris, R. P. Regulation of the fructose transporter GLUT5 in health and disease. Am. J. Physiol.-Endocrinol. Metab. 295, E227–E237 (2008).

Sörensen, I., Adams, R. H. & Gossler, A. DLL1-mediated Notch activation regulates endothelial identity in mouse fetal arteries. Blood 113, 5680–5688 (2009).

Tanigaki, K. et al. Notch–RBP-J signaling is involved in cell fate determination of marginal zone B cells. Nat. Immunol. 3, 443–450 (2002).

Agalave, N. M., Lane, B. T., Mody, P. H., Szabo-Pardi, T. A. & Burton, M. D. Isolation, culture, and downstream characterization of primary microglia and astrocytes from adult rodent brain and spinal cord. J. Neurosci. Methods 340, 108742 (2020).

Schmittgen, T. D. & Livak, K. J. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative CT method. Nat. Protoc. 3, 1101–1108 (2008).

Acknowledgements

We thank Ohio University IACUC and Laboratory for Animal Research for animal care, Ohio University Neuroscience Program for confocal microscope access, Ohio University Histology Core for cryostat access, and Michelle Pate for assistance with FACS at the Ohio University Flow Cytometry Core.

Funding

This research was supported by Ohio University Student Enhancement Award, College of Arts and Sciences Graduate Award, and Neuroscience Program Confocal Microscopy to S.N.; NIH/NINDS 3R03 NS137135-01S1 to K.F.; Ohio University Program to Aid Career Exploration to J.L.; Summer Neuroscience Undergraduate Research Fellowship to L.J.A.; The Aneurysm and AVM Foundation UT 22563, NIH/NINDS R15 NS111376, and NIH/NINDS R03 NS137135 to C.M.N.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.N. contributed experimental design, data acquisition, and data analysis for all Figures and Supplementary Figures and Tables; K.F. contributed experimental design, data acquisition, and data analysis for Figs. 1, 5 and Supplementary Figs. 1, 2. J.L. contributed data acquisition and data analysis for Figs. 3, 4 and Supplementary Figs. 3, 4, 6. L.J.A. contributed data acquisition for Figs. 1, 5 and Supplementary Fig. 2. S.N. and K.F. prepared figures. S.N. and C.M.N. conceptually designed the research, interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nakisli, S., Fanelli, K., LaComb, J. et al. CNS resident macrophages exhibit region-specific states and immunogenic responses during Rbpj-deficient brain arteriovenous malformation. Sci Rep 15, 3932 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86150-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86150-4