Abstract

Calcium hydroxide nanoparticles (Ca(OH)2NPs) possess potent antimicrobial activities and unique physical and chemical properties, making them valuable across various fields. However, limited information exists regarding their effects on genomic DNA integrity and their potential to induce apoptosis in normal and cancerous human cell lines. This study thus aimed to evaluate the impact of Ca(OH)2NPs on cell viability, genomic DNA integrity, and oxidative stress induction in human normal skin fibroblasts (HSF) and cancerous hepatic (HepG2) cells. Cell viability and genomic DNA stability were assessed using the Sulforhodamine B (SRB) assay and alkaline comet assay, respectively. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels were measured using 2,7-dichlorofluorescein diacetate, while the expression level of apoptosis-related genes (p53, Bax, and Bcl-2) were quantified using real-time PCR (qRT-PCR). The SRB cytotoxicity assay revealed that a 48-hour exposure to Ca(OH)2NPs caused concentration-dependent cell death and proliferation inhibition in both HSF and HepG2 cells, with IC50 values of 271.93 µg/mL for HSF and 291.8 µg/mL for HepG2 cells. Treatment with the IC50 concentration of Ca(OH)2NPs selectively induced significant DNA damage, excessive ROS generation, and marked dysregulation of apoptotic (p53 and Bax) and anti-apoptotic (Bcl-2) gene expression in HepG2 cells, triggering apoptosis. In contrast, exposure of HSF cells to the IC50 concentration of Ca(OH)2NPs caused no significant changes in genomic DNA integrity, ROS generation, or apoptotic gene expression. These findings indicate that Ca(OH)2NPs exhibit concentration-dependent cytotoxicity in both normal HSF and cancerous HepG2 cells. However, exposure to the IC50 concentration was non-genotoxic to normal HSF cells while selectively inducing genotoxicity and apoptosis in HepG2 cancer cells through DNA breaks and ROS-mediated mechanisms. Further studies are required to explore the biological and toxicological properties and therapeutic potential of Ca(OH)2NPs in hepatic cancer treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Calcium hydroxide nanoparticles (Ca(OH)2NPs) have garnered significant interest across diverse fields due to their distinctive physicochemical properties. These include high reactivity, a large surface area-to-volume ratio, enhanced cell membrane penetration, and superior antimicrobial activity compared to their bulk counterparts. In medicine, Ca(OH)2NPs are utilized in dental materials and wound healing applications. Similarly, in the construction industry, they play a role in concrete production and wastewater treatment1,2,3.

As the use of Ca(OH)2NPs expands across various industries and medical fields, the potential for human exposure to these nanoparticles is increasing. Common exposure routes include inhalation, ingestion, and skin contact, contributing to their presence in everyday products and environments4,5. This heightened exposure has raised concerns regarding their potential health impacts, prompting extensive research into the safety and toxicity of Ca(OH)2NPs6,7.

The toxicity of Ca(OH)2NPs remains a subject of ongoing research and debate. While these nanoparticles offer significant potential across various applications, their possible health risks warrant careful consideration. Studies have shown that prolonged exposure to high concentrations of Ca(OH)2NPs can lead to respiratory issues, skin irritation, oxidative stress, and other health concerns5,8. However, research by de Souza and colleagues highlights the safety of Ca(OH)2NPs in human dental pulp mesenchymal cells, demonstrating that exposure did not compromise cell viability and even reduced the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and nitric oxide9.

The genotoxic effects of Ca(OH)2NPs have attracted considerable attention in recent studies. In vivo studies have revealed their genotoxicity, showing that exposure to Ca(OH)2NPs can cause genomic and mitochondrial DNA damage, excessive ROS generation, and alterations in inflammatory and apoptotic gene expression in tissues such as bone marrow, liver, brain, stomach, and kidneys in mice3,4,6,10.

Understanding the cytotoxicity and genotoxicity of Ca(OH)2NPs across a broader range of cell lines and experimental systems is crucial for evaluating their safety, developing effective risk management strategies, and exploring their therapeutic potential. However, existing data are limited, with only a few studies examining the cytotoxic and genotoxic effects of Ca(OH)2NPs on different human normal and cancer cell lines.

To address this gap, the present study was conducted to investigate the impact of Ca(OH)2NPs exposure on cell viability, genomic DNA integrity, and ROS generation in human normal skin fibroblast (HSF) and hepatocellular carcinoma (HepG2) cells. Cell viability was assessed using the Sulforhodamine B (SRB) cytotoxicity assay, while genomic DNA integrity and ROS generation level was evaluated using the alkaline Comet assay and 2’,7’-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFDA) dye, respectively. The expression level of apoptosis related genes was also measured using quantitative real time PCR (qRT-PCR).

Materials and methods

Chemicals

White powders of Ca(OH)2NPs were purchased from Nano Tech company Egypt with size less than 100 nm. Prior treatment, Ca(OH)2NPs were suspended and ultra-sonicated in deionized distilled water to prepare the tested concentrations. All the remaining used chemicals and reagents in the conducted experiments were of high analytical and molecular biology grade.

Characterization of ca(OH)2NPs

The characterization of Ca(OH)2NPs was carried out to ensure their purity and evaluate their physicochemical properties. X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis was performed using a charge-coupled device diffractometer (XPERT-PRO, PANalytical, Netherlands) to confirm the purity of the purchased nanoparticles. The zeta potential and particle size distribution were analyzed using a Malvern Zetasizer Nano Series (Malvern Instruments, Westborough, MA). Additionally, the morphology and average size of the Ca(OH)2NPs were determined through transmission electron microscopy (TEM) imaging.

Cell lines

Normal Human Skin Fibroblast (HSF) and hepatocellular carcinoma (HepG2) cells were supplied from Nawah Scientific Company (Mokatam Cairo Egypt) and were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) media supplemented with 100 mg/mL of streptomycin, 100 units/mL of penicillin and 10% of heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum in humidified, 5% (v/v) CO2 atmosphere at 37 °C.

Cell viability

The Sulforhodamine B (SRB) assay was performed to evaluate the viability of normal HSF and HepG2 cells following 48 h of treatment with Ca(OH)2NPs11. A 100 µL suspension containing 5 × 103 cells was seeded into 96-well plates and incubated for 24 h in complete media. After incubation, the cells were treated with 100 µL of media containing Ca(OH)2NPs at different concentrations (0.1, 1, 10, 100, and 1000 µg/ml). After 48 h of exposure to the nanoparticles, the cells were fixed by replacing the media with 150 µL of 10% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) and incubating at 4 °C for 1 h. The TCA solution was then removed, and the cells were washed five times with distilled water. Next, 70 µL of 0.4% (w/v) SRB solution was added to each well, and the plates were incubated in the dark at room temperature for 10 min. Unbound dye was removed by washing the plates three times with 1% acetic acid, and the plates were allowed to air-dry overnight. Finally, 150 µL of 10 mM TRIS solution was added to dissolve the protein-bound SRB stain, and the absorbance was measured at 540 nm using an Infinite F50 microplate reader (TECAN, Switzerland).

Treatment schedule

Normal HSF and cancerous HepG2 cells were cultured separately under the proper conditions and divided into control and treated cells. Control cells were exposed to an equivalent volume of the vehicle (DMSO; final concentration, ≤ 0.1%), while treated HSF and cancer HepG2 cells were exposed to Ca(OH)2NPs at the IC50 concentration determined using SRB assay. After 48 h of treatment, both control and treated cells were harvested by trypsinization and centrifugation. Each treatment was done in triplicate, and cells were washed twice with ice-cold PBS and stored at -80 C° for different molecular studies.

Detection of genomic DNA stability

The impact of Ca(OH)2NPs on the integrity of genomic DNA was assessed in the treated and untreated HSF and cancer HepG2 cells using Alkaline Comet assay12,13. A 15 µl of cell suspension was mixed with 60 µl of low melting agarose, mixed well and then spread on slides pre-coated with normal melting agarose. After gel hardening, all slides were placed in a lysis buffer with PH of 10 and freshly added triton X-100 and Dimethyl sulfoxide for 24 h in dark. After lysis, slides were washed with distilled water and incubated in an alkaline electrophoresis buffer with PH higher than 12 to unwind double stranded DNA. Then electrophoresis was run for 30 min with current 300 mAmp and 35 Volts. Subsequent to electrophoresis, pH neutralization was done using Tris buffer to reanneal single stranded DNA. After that, DNA was fixed with absolute ethanol for permanent preservation. Finally, slides were stained by ethidium bromide and photography was done using epi-fluorescent microscope at magnification 200 × and fifty comet nuclei were analyzed using Comet Score TM software and DNA damage indicating parameters (tail length, %DNA in tail and tail moment) were measured for each sample.

Tail Length: The distance the DNA fragments migrate from the nucleus. A longer tail indicates more DNA damage.

% DNA in tail: The percentage of total DNA that is found in the tail. A higher percentage indicates more DNA fragmentation.

Tail Moment: A measure that combines the tail length and the percentage of DNA in the tail. It provides a quantitative assessment of DNA damage, with a higher tail moment indicating greater damage.

Studying the generation level of intracellular ROS

The effect of Ca(OH)2NPs on the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) within HSF and cancer HepG2 cells was also screened using 2,7-dichlorofluorescein diacetate dye that enters cells passively and reacts with ROS forming the highly fluorescent dichlorofluorescein product14. A cell suspension was mixed with 2,7-dichlorofluorescein diacetate dye and Aincubated in dark for 30 min. After incubation this mixture was spread on a clean slide and the emitted fluorescent light was validated using epi-fluorescent at 200 × magnification.

Measurement of apoptosis related gene expression

Influence of Ca(OH)2NPs on the mRNA expression level of p53, Bax and Bcl2 genes in the untreated and treated HSF and cancer HepG2 cells was studied using Quantitative Real Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRTPCR). The GeneJET RNA Purification Kit (Thermo scientific, USA) (Thermo scientific, USA) was first used to extract the total cellular RNA that was converted subsequently into complementary DNA (cDNA) using the Revert Aid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo scientific, USA). The obtained cDNA of p53, Bax and Bcl2 genes were finally amplified using SYBER Green master mix and the primers sequence shown in Table 115,16 by the 7500 Fast system (Applied Biosystem 7500, Clinilab, Egypt). The mRNA expression level of the studied apoptotic and anti-apoptotic genes was then determined using the comparative Ct (DDCt) method after standardization using the housekeeping GAPDH gene expression. The final results were expressed as mean ± S.D.

Statistical analysis

The obtained results were displayed as mean ± Standard Deviation (S.D) and were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) (version 20) at the significance level p < 0.05. One Way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) followed by Duncan’s test was done to compare the control HSF cells to the treated HSF cells, control HepG2 cells and treated HepG2 cells.

Results

Characterization of ca(OH)2NPs

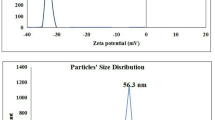

Characterization of Ca(OH)2NPs using XRD Analysis proved the purity of the purchased nanoparticles by the appearance of distinctive bands for Ca(OH)2NPs at the diffraction angles 18º, 29º and 34º (Fig. 1). Analysis of Zeta potential and particles size distribution revealed high aggregation and large hydrodynamic size of the suspended Ca(OH)2NPs as manifested from the reported Zeta potential value of 2.45 mV and a polydispersity index (PdI) value of 0.416 for Ca(OH)2NPs (Fig. 2). Moreover, imaging of the ultra-sonicated Ca(OH)2NPs suspension using TEM showed Ca(OH)2NPs have cubic and spherical shape and are well dispersed with an average particle size of 12.4 ± 2.4 nm as seen in Fig. 3.

Ca(OH)2NPs induce death of normal HSF and cancerous HepG2 cells

As seen in Fig. 4 treatment with five different concentrations of Ca(OH)2NPs (0.1, 1, 10, 100–1000 µg/ml) caused a marked reduction in the viability of HSF and HepG2 cells only at their highest concentration (1000 µg/ml). The IC50 value of Ca(OH)2NPs was equal 271.93 µg/ml for normal HSF cells and 291.80 µg/ml for hepatic cancer HepG2 cells (Fig. 4).

Ca(OH)2NPs selectively induced DNA damage in HepG2 cancerous cells

The results presented results for alkaline Comet assay in Table 2; Fig. 5 revealed that exposure of HepG2 cells to the IC50 concentration (291.80 µg/ml) of Ca(OH)2NPs highly disrupted the integrity of genomic DNA in cancerous HepG2 cells as appeared from the statistical significant elevations (p < 0.05) in the measured DNA damage parameters: tail length, %DNA in tail and tail moment seen 48 h after HepG2 cells treatment with Ca(OH)2NPs compared to their values in untreated HepG2 cells (Table 2). In contrast, normal HSF cells treatment with IC50 concentration (271.93 µg/ml) of Ca(OH)2NPs did not affect the genomic DNA integrity as the measured tail length, and tail moment were non-significantly changed, even %DNA in tail was markedly decreased in the HSF cells treated with Ca(OH)2NPs compared to the measured values of untreated HSF cells (Table 2).

Ca(OH)2NPs selectively dysregulated the mRNA expression level of p53, Bax and Bcl2 genes in HepG2 cancerous cells

The interpretation of qRTPCR results manifested the dysregulation of apoptotic and anti-apoptotic genes expression in the HepG2 cancerous cells treated with Ca(OH)2NPs at an IC50 concentration (291.80 µg/ml) for 48 h through the remarkable elevations in the expression level of apoptotic p53 and Bax genes and a noticeable decrease in the anti-apoptotic Bcl2 gene expression observed in the HepG2 cells treated with Ca(OH)2NPs compared to their expression level in the untreated HepG2 cells (Table 3). On the other hand, non-remarkable variations were seen in the expression level of p53, Bax and Bcl2 genes 48 h after HSF cells treatment with IC50 concentration (271.93 µg/ml) of Ca(OH)2NPs compared to the untreated HSF cells expression level (Table 3).

Ca(OH)2NPs selectively over-generated ROS within HepG2 cancerous cells

As displayed in Fig. 6, treatment of HepG2 cancerous cells with the IC50 concentration (291.80 µg/ml) of Ca(OH)2NPs for 48 h caused remarkable overproduction of ROS within as shown from the noticeable increase in the intensity of fluorescent light emitted from the treated HepG2 cells compared to that emitted from untreated HepG2 cells (Fig. 6). However, no marked variations were observed in the generation level of ROS after 48 h of HSF treatment with the IC50 concentration (271.93 µg/ml) of Ca(OH)2NPs as depicted in Fig. 7 by the non-remarkable changes in the observed in the intensity of fluorescent light emitted from the treated HSF cells compared to that emitted from untreated HSF cells.

Discussion

The recent discovery of the potent antimicrobial properties of Ca(OH)2NPs has increased their uses in biomedicine, environmental science, food industry and agriculture8. However, However, there is limited information regarding the impact of Ca(OH)2NPs on cell viability and genomic DNA integrity in both normal and cancerous human cells. Therefore, this study was conducted to assess the effect of Ca(OH)2NP exposure on cell viability, genomic stability, and ROS generation in normal human HSF cells and cancerous HepG2 cells.

Normal HSF cells are widely used as a model for non-cancerous human tissue in toxicity studies due to their availability, robustness, and ability to provide insights into the general cytotoxic effects of nanoparticles on healthy cells. Similarly, HepG2 cells, a well-established human hepatocellular carcinoma cell line, are extensively employed in cancer research to evaluate anticancer effects, drug delivery systems, and nanoparticle efficacy. Using HSF and HepG2 cells together in this study aligns with previous research17,18 and facilitates a comparative assessment of the cytotoxicity of Ca(OH)2NPs on normal versus cancerous cells.

The discrepancy between particle size distribution measured by Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) and Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) arises from differences in their principles and contexts. DLS measures the hydrodynamic diameter, which accounts for the particle core as well as any surrounding solvent layer, surface-bound molecules, or adsorbed ions, leading to larger size estimates. In contrast, TEM provides a direct measurement of the core size by imaging the physical dimensions of particles under a microscope. Additionally, DLS is more sensitive to particle aggregates because it detects the collective scattering of light, meaning even minor aggregation can skew the size distribution toward larger values. On the other hand, TEM typically captures particles as individuals due to sample preparation (e.g., drying on a grid), making aggregates less likely to appear unless specifically observed19,20.

The cytotoxicity of Ca(OH)2NPs was manifested in this study through the marked concentration-dependent proliferation inhibition and reduced viability of normal HSF cells and cancerous HepG2 cells noticed 48 h after Ca(OH)2NPs treatment with IC50 values of 271.93 µg/ml for HSF cells and 291.80 µg/ml for HepG2 cells. These results supported the recent study by Prasetyo and his colleagues21 that demonstrated the cytotoxicity of Ca(OH)2NPs on human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells.

Regarding genotoxicity, although Ca(OH)2NPs were not genotoxic to normal HSF cells, they were highly genotoxic to HepG2 cancer cells as demonstrated by marked increases in the measured parameters of DNA damage: tail length, %DNA in tail and tail moment observed in Ca(OH)2NPs treated HepG2 cells in contrast to the non-significant changes seen in tail length, %DNA in tail and tail moment after HSF cells exposure to Ca(OH)2NPs. Alkaline Comet assay is a highly sensitive cyto-molecular genetic technique for detecting DNA damage. It sensitively detects both single- and double-stranded DNA breaks12,22. Consequently, our findings of significant elevations in the measured alkaline Comet parameters revealed marked induction of DNA breaks 48 h after exposure of HepG2 cancer cells to Ca(OH)2NPs.

The induction of high DNA damage poses a significant threat as it triggers excessive ROS generation and can ultimately result in cell death. Research has shown that even a single DNA break can disrupt the integrity of genomic DNA, leading to cellular death22,23,24. Cellular ROS, highly reactive metabolites, are produced within cells during cellular processes, and play a crucial role in cellular signaling. However, ROS are produced in excess when the balance between oxidants and antioxidants is disrupted; thereby these overproduced ROS attack and cause damage to cellular macromolecules: lipid, proteins, carbohydrates and DNA inducing oxidative stress25,26,27. Excessive ROS generation by Ca(OH)2NPs in HepG2 cancer cells was demonstrated by the remarkable elevations noticed in the intensity of fluorescent light emitted from the Ca(OH)2NPs-treated HepG2 cells compared to that emitted from untreated HepG2 cells.

As a result, the demonstrated cytotoxicity of Ca(OH)2NPs against HepG2 cancer cells in this study may result from the above-mentioned induction of marked DNA breaks and excessive ROS generation in HepG2 cancer cells treated with Ca(OH)2NPs because high induction of DNA damage and increased ROS generation forced cells to die through the apoptotic pathway28,29. Our data of qRTPCR demonstrated that exposure to Ca(OH)2NPs for 48 h trigger apoptosis of HepG2 cells through the concurrent marked upregulation of the apoptotic (p53 and Bax) genes’ expression level and a significant decrease in the anti-apoptotic Bcl2 gene expression level noticed after treatment of HepG2 cancer cells with Ca(OH)2NPs.

On the other hand, the non-remarkable changes in of ROS generation level and expression level of p53, Bax and Bcl2 genes noticed after HSF cells treatment with IC50 concentration of Ca(OH)2NPs confirmed the safety and non-genotoxicity of Ca(OH)2NPs on HSF normal cells. This non-genotoxic effect of Ca(OH)2NPs on HSF normal cells may result from the genomic stability and regulation of different DNA repair mechanisms that enable normal HSF cells to maintain genomic DNA and cell integrity30,31. However, Ca(OH)2NPs cytotoxicity to normal HSF cells can be attributed to the excessive release of calcium ions that directly attack the cell membrane causing loss of its selective permeability and thereby cell death32.

The high specificity and increased toxicity of Ca(OH)2NPs to HepG2 cancer cells are largely due to the pH differences between normal and cancer cells. Cancer cells are characterized by an acidic extracellular pH (acidic microenvironment), whereas normal cells maintain a more neutral extracellular pH and tightly regulated intracellular pH levels. As a result, the high alkalinity of Ca(OH)2NPs induces a more pronounced genotoxic effect on cancer cells due to their acidic environment. Cancer cells are unable to effectively counteract the significant pH changes caused by hydroxide ions and excessive ROS generation, leading to damage to cellular structures, including DNA. In contrast, normal cells, operating in a more neutral pH environment, are better able to manage or resist these pH changes, resulting in less toxicity33,34,35. Consequently, this study demonstrated for the first time the strong cytotoxicity and potent selective genotoxicity of Ca(OH)2NPs against cancerous HepG2 cells. Future studies will address the limitations of this study, including the use of only two cell lines, the short exposure time, and the absence of additional molecular analyses, such as flow cytometry and Western blot.

Conclusion

Collectively from the data discussed above, it was concluded that Ca(OH)2NPs induced concentration-dependent cytotoxicity on normal HSF and cancer HepG2 cells. However, exposure to Ca(OH)2NPs at IC50 concentration for 48 h was non-genotoxic in normal HSF cells and selectively disrupts the genomic DNA integrity of HepG2 cancer cells through induction of high DNA damage, excessive ROS generation and alterations of the expression level of apoptotic genes. Therefore, further studies on the biological and toxicological properties of Ca(OH)2NPs along with possibility of their usage in cancer therapy are recommended.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

El Bakkari, M., Bindiganavile, V. & Boluk, Y. Facile synthesis of calcium hydroxide nanoparticles onto TEMPO-oxidized cellulose nanofibers for heritage conservation. ACS Omega. 4 (24), 20606–20611 (2019).

Vyerchenko, L. et al. The study of calcium hydroxide structure and its physico-chemical and electrokinetic properties in sugar production. Chem. Chem. Technol. 13 (4), 477–481 (2019).

Mohamed, H. R. H. et al. Alleviation of calcium hydroxide nanoparticles induced genotoxicity and gastritis by coadministration of calcium titanate and yttrium oxide nanoparticles in mice. Sci. Rep. 13, 22011. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-49303-x (2023).

Hanan, R. H. M. Estimation of genomic instability and mitochondrial DNA damage induction by acute oral administration of calcium hydroxide normal- and nano- particles in mice. Toxicol. Lett. 304, 1–12 (2019).

Xuan, L., Ju, Z., Skonieczna, M., Zhou, P. K. & Huang, R. Nanoparticles-induced potential toxicity on human health: Applications, toxicity mechanisms, and evaluation models. MedComm 4(4), e327 (2023).

Mohamed, H. R. H. et al. Genotoxicity and oxidative stress induction by calcium hydroxide, calcium titanate or/and yttrium oxide nanoparticles in mice. Sci. Rep. 13, 19633. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-46522-0 (2023).

Mohamed, H. R. H., Farouk, A. H., Elbasiouni, S. H., Nasif, A. A. & Gehan Safwat Yttrium oxide nanoparticles ameliorates calcium hydroxide and calcium titanate nanoparticles induced genomic DNA and mitochondrial damage, ROS generation and inflammation. Sci. Rep. 14, 13015 (2024).

Dianat, O., Saedi, S., Kazem, M. & Alam, M. Antimicrobial activity of nanoparticle calcium hydroxide against Enterococcus Faecalis: an in vitro study. Iran. Endod J. 10 (1), 39–43 (2015).

de Souza, G. L., Almeida Silva, A. C., Dantas, N. O., Silveira Turrioni, A. P. & Moura, C. C. G. Cytotoxicity and effects of a New Calcium Hydroxide Nanoparticle Material on production of reactive oxygen species by LPS-Stimulated Dental Pulp cells. Iran. Endod J. 15 (4), 227–235 (2020).

Mohamed, H. R. H. Induction of genotoxicity and differential alterations of p53 and inflammatory cytokines expression by acute oral exposure to bulk- or nano-calcium hydroxide particles in mice; genotoxicity of normal- and nano-calcium hydroxide. Toxicol. Mech. Methods. 31 (3), 169–181 (2021).

Allam, R. M. et al. Fingolimod interrupts the cross talk between estrogen metabolism and sphingolipid metabolism within prostate cancer cells. Toxicol. Lett. Apr. 11 (291), 77–85 (2018).

Tice, R. R. et al. Single cell gel/comet assay: guidelines for in vitro and in vivo genetic toxicology testing. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 35, 206–221 (2000).

Langie, S. A., Azqueta, A. & Collins, A. R. The comet assay: past, present, and future. Front. Genet. 6, 266 (2015).

Siddiqui, M. A. et al. Protective potential of trans-resveratrol against 4-hydroxynonenal induced damage in PC12 cells. Toxicol. Vitro. 24, 1592–1598 (2010).

Suzuki, K. et al. Drug- induced apoptosis and p53, BCL-2 and BAX expression in breast cancer tissues in vivo and in fibroblast cells in vitro. Jpn J. Clin. Oncol. 29 (7), 323–331 (1999).

Lai, C. Y. et al. Aciculatin induces p53-dependent apoptosis via mdm2 depletion in human cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. PLoS ONE. 7 (8), e42192 (2013).

Abdallah, S. et al. The selective cytotoxicity effect of biosynthesized zinc oxide nanoparticles using honey. Mater. Lett. 367, 136657(1) (2024).

Xuan, L., Ju, Z., Skonieczna, M., Zhou, P. K. & Huang, R. Nanoparticles-induced potential toxicity on human health: Applications, toxicity mechanisms, and evaluation models. MedComm 4(4), e327 . https://doi.org/10.1002/mco2.327 (2023).

Maguire, C. M., Rösslein, M., Wick, P. & Prina-Mello, A. Characterisation of particles in solution - a perspective on light scattering and comparative technologies. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 19(1), 732–745 (2018).

Souza, T. G. F. & Ciminelli, V. S. T. 2 and N. D. S. Mohallem A comparison of TEM and DLS methods to characterize size distribution of ceramic nanoparticles. J. Phys.: Conf. Ser. 733, 012039 (2016).

Prasetyo, E. P. et al. Cytotoxicity of Calcium Hydroxide on Human Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stem Cells20 (Pesquisa Brasileira Em Odontopediatria E Clínica Integrada, 2020). e0044.

Pu, X., Wang, Z. & Klaunig, J. E. Alkaline Comet Assay for Assessing DNA Damage in Individual Cells. Curr. Protoc. Toxicol. 65, 3.12.1–3.12.11 (2015).

Kaina, B. DNA damage-triggered apoptosis: critical role of DNA repair, double-strand breaks, cell proliferation and signaling. Biochem. Pharmacol. 15 (8), 1547–1554 (2003).

Jensen, R. B. & Rothenberg, E. Preserving genome integrity in human cells via DNA double-strand break repair. Mol. Biol. Cell. 31(9), 859–865 (2020).

Valko, M., Rhodes, C. J., Moncol, J., Izakovic, M. & Mazur, M. Free radicals, metals and antioxidants in oxidative stress-induced cancer. Chem. Biol. Interact. 160, 1–40 (2006).

Birben, E., Sahiner, U. M., Sackesen, C., Erzurum, S. & Kalayci, O. Oxidative stress and antioxidant defense. World Allergy Organ. J. 5 (1), 9–19 (2012).

Kang, M. A., So, E-Y., Simons, A. L., Spitz, D. R. & Ouchi, T. DNA damage induces reactive oxygen species generation through the H2AX-Nox1/Rac1 pathway. Cell. Death Dis. 3 (1), e249 (2012).

De Zio, D., Cianfanelli, V. & Cecconi, F. New insights into the link between DNA damage and apoptosis. Antioxid. Redox. Signal. 19(6), 559–571 (2013).

Zhao, Y. et al. Cancer Metabolism: The Role of ROS in DNA Damage and Induction of Apoptosis in Cancer Cells13796 (Metabolites, 2023). 7.

Alhmoud, J. F., Woolley, J. F., Al Moustafa, A. E. & Malki, M. I. DNA damage/repair Manage. Cancers Cancers 12(4):1050 (2020).

Křenek, T., Kovářík, T., Pola, J., Stich, T. & Docheva, D. Nano and micro-forms of calcium titanate: synthesis, properties and application. Open. Ceram. 8, 100177 (2021).

Karlsson, H. L. et al. Cell membrane damage and protein interaction induced by copper containing nanoparticles—importance of the metal release process. Toxicology 313 (1), 59–69 (2013).

Mustafa, M. et al. Apoptosis: a Comprehensive Overview of Signaling pathways, morphological changes, and physiological significance and therapeutic implications. Cells 13 (22), 1838. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells13221838 (2024).

Ward, C. et al. The impact of tumour pH on cancer progression: strategies for clinical intervention. Explor. Target. Antitumor Ther. 1 (2), 71–100. https://doi.org/10.37349/etat.2020.00005 (2020).

Koltai, T. Cancer: fundamentals behind pH targeting and the double-edged approach. Onco Targets Ther. 9, 6343–6360. https://doi.org/10.2147/OTT.S115438 (2016).

Acknowledgements

Great thanks and appreciation to the Department of Zoology, Faculty of Science, Cairo University, for providing us with the required chemicals and equipment to conduct experiments.

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

The present work was partially funded by Faculty of Science Cairo University and Faculty of Biotechnology, October University for Modern Sciences and Arts (MSA) Egypt.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Hanan RH Mohamed: designed the study and performed the molecular experiments, wrote manuscript and conducted statistical analysis. Esraa Ibrahim, Shahd Shaheen and Nesma Hussein performed experimentations and wrote manuscript. Gehan Safwat, Ayman Diab and all authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mohamed, H.R.H., Ibrahim, E.H., Shaheen, S.E.E. et al. Calcium hydroxide nanoparticles induce cell death, genomic instability, oxidative stress and apoptotic gene dysregulation on human HepG2 cells. Sci Rep 15, 2993 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86401-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86401-4

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Calcium hydroxide nanoparticles induce apoptotic cell death in human pancreatic cancer cells through over ROS-driven genomic instability and mitochondrial dysfunction

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Erbium oxide nanoparticles induce potent cell death, genomic instability and ROS-mitochondrial dysfunction-mediated apoptosis in U937 lymphoma cells

Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology (2025)

-

Bioactive glass nanoparticles induce strong preferential cytotoxicity and excessive ROS-mediated oxidative stress and apoptotic genomic DNA damage in non-small lung cancer cells

Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology (2025)