Abstract

The aim of this study was to determine whether there is a difference in the degree of apoptosis and the pathways leading to necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) between preterm and full-term rat pups. To achieve this goal, we investigated the pathogenesis of NEC. premature Sprague‒Dawley (SD) rat pups delivered by cesarean section at a gestational age of 21 days (preterm group), as well as full-term SD rat pups four days after birth (full-term group). The pups were exposed to lipopolysaccharides (LPS) and hypoxia to induce necrotizing enterocolitis. Both preterm and full-term rats developed necrotizing enterocolitis. The results indicated that the degree of apoptosis was greater in both the preterm and full-term NEC groups than in the untreated preterm and full-term control groups. Compared with the control group, the full-term group also presented a reduction in Bcl-2 levels and an increase in the ratio. Moreover, the preterm group presented significantly increased RIPK1 expression, suggesting the induction of RIPK1-dependent apoptosis. These findings suggest that the pathophysiology of necrotizing enterocolitis induced by LPS + hypoxia is associated with the programmed cell death pathway. It appears that the apoptotic pathway of the Bax/Bcl-2 system is the main mechanism of necrotizing enterocolitis in full-term rats. In contrast, several other mechanisms, including TNF-α-induced apoptosis mechanism, may work together for necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm rats. However, further studies are needed to elucidate the differences in the pathogenesis of necrotizing enterocolitis development between preterm and full-term rats.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) is the most common surgical emergency affecting the gastrointestinal tracts of infants. Even with proper surgical or medical treatment, NEC can result in intestinal obstruction, short bowel syndrome, growth restriction, and developmental delays1,2. Although NEC is recognized as a very important disease that can affect the health and survival of premature infants, the pathogenesis of NEC remains unclear. At present, the known risk factors for NEC include prematurity, hypoxic-ischemic injury, formula feeding, and bacterial colonization3,4. Patients suffering from NEC exhibit a loss of gastrointestinal motility, intestinal mucosal damage, and inflammation, ultimately resulting in apoptosis and necrosis5. Extensive apoptosis has also been observed in the resected intestine of patients with NEC, while apoptotic enterocytes have been reported in several NEC mouse models6,7,8.

Necroptosis is a programmed form of cell death. Studies have identified receptor interacting protein kinase-1 (RIPK1), receptor interacting protein kinase-3 (RIPK3), and mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein (MLKL) as key mediators that induce the necroptosis pathway9,10. The activation of RIPK1 by metabolic stress and hypoxia may contribute to the triggering of ischemic damage in multiple organs11,12,13. Apoptosis can be induced by the presence of two death factors, Fas ligand (FasL) or tumor necrosis factor (TNF), in turn leading to the activation of caspase-8 through the recruitment of FADD9,14,15,16. Apoptosis, the cell death induced by DNA damage, could be activated and promote pro-apoptotic proteins, including BAX and BAK17. Previous studies in the field of programmed cell death mechanisms have examined BAX−/−BAK−/−18. The Bcl-2 family, which includes the Bax, BH3, and Bcl2 subfamilies, comprises cytoplasmic proteins that serve as critical regulators of apoptosis10,19,20.

Various animal models have been proposed to clarify NEC pathogenesis, including ischemia‒reperfusion injury, formula feeding with cold asphyxia, and injections of PAF, TNF, and LPS21,22,23,24,25. A recent study reported that NEC could be induced by LPS administration (5 mg/kg orally) plus repeated hypoxic exposure (5% O2) on rats26. In this study, NEC was induced in both preterm and full-term rats by LPS and repeated hypoxia. To understand the pathogenesis of NEC, a comparative analysis was performed to examine the changes in ileal morphology, apoptosis, and various apoptosis-related proteins in preterm and full-term rats.

Materials and methods

Procurement of samples

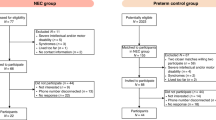

The research was carried out with 4 pregnant Sprague‒Dawley female rats (KOATECH, Pyeongtaek, Korea). Forty preterm rats were delivered by cesarean section at 21 days of gestation, and forty full-term rats, 4 days old at the time of the experiment, were used. The average weights of the full-term and preterm rats were 10.8 g (10.2–11.2 g) and 5.5 g (4.6–5.6 g), respectively. The rats were ultimately divided into four groups: (1) preterm rats (delivered from the uterus on the 21st day of gestation); control (n = 20), (2) preterm rats treated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS 5 mg/kg) + hypoxia (5% O₂); preterm NEC (n = 20), (3) full-term rats (4 days after birth); control (n = 20), and (4) full-term rats treated with LPS (5 mg/kg) + hypoxia (5% O₂); full-term NEC (n = 20).

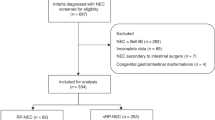

Induction of NEC by lipopolysaccharide and hypoxia

For the induction of NEC, the preterm and full-term rats in the experimental groups were exposed to two factors. First, 5 mg/kg endotoxin—LPS from Escherichia coli 0111 (O111:B4), which was purified by gel filtration chromatography (Sigma‒Aldrich, St. Louis, USA)—was administered enterally through a polyethylene tube. For hypoxia, the experimental group of animals was placed in a hypoxic chamber (Glass Lake Coy LAB, Michigan, USA) under 5% hypoxic conditions for 1 h and then moved to normal air conditions for 1 h. This process was repeated three times. For the control groups, equivalent volumes of saline were administered instead of LPS, and the animals were exposed to normal air conditions instead of hypoxic conditions (Fig. 1). The animals were sacrificed 8 h after the start of the experiment by decapitation. After laparotomy, approximately 18 cm of the terminal ileum above the ileocecal valves was obtained for assays. The experiments were approved by the Seoul National University Hospital Animal Ethics Committee (IACUC No. 23–0198-S1A02), and all methods followed their guidelines and regulations. This study is reported in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines.

NEC was induced by LPS and hypoxic conditions. (a) Diagram of the experimental protocol. LPS was administered to the NEC group, and normal saline was administered to the control group at the beginning of the experiment through a polyethylene tube in the stomach. In the NEC group, 60 min of hypoxia (5%) was applied at 2, 4, and 6 h. The animals were sacrificed at 8 h. (b) Establishment of a necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) rat pup model. In the full-term control and full-term NEC groups, the ileum can be observed as a dark color change, as indicated by arrows; in the preterm control group and preterm NEC group, the ileum can be observed as a dilatation of the small bowel, a dark color change, and the inclusion of air bubbles, as indicated by arrows.

Pathological assessment of NEC progression

Specimens were cut into 4 μm sections, formalin fixed, and then stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE) for histological evaluation. We evaluated the progression of NEC according to the Jilling scoring system (Table 1)28. The highest score observed in a sample was the representative score of that sample.

Evaluation of apoptosis in the samples

For apoptosis scoring, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP-FITC nick-end labeling (TUNEL) staining was applied to formalin-fixed sections according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). The degree of apoptosis in each sample was assessed as described in the Jilling scoring system (Table 2.)28. The highest score observed in the stained section was considered the representative score of the sample.

RNA extraction and real-time reverse transcription (RT)-PCR

Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Rockford, IL, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The isolated RNA samples were converted to cDNA using a high-capacity RNA-to-cDNA kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA). All PCRs were performed with power SYBR® Green PCR Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA) on a 7500 Real-time PCR System (Applied Biosystems Foster City, CA, USA) in standard 20 µl reactions. Supplementary Table 1 lists the primers used for qPCR. The data were standardized to those of GAPDH, which was used as a housekeeping gene for all samples, and relative expression levels were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method.

Western blot

Total protein was extracted from homogenized intestinal ileum tissues using Tissue Extraction Reagent I (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA) with protease inhibitor cocktails and phenylmethanesulfonylfluoride (PMSF) (100:1 ratio) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA). Protein concentrations were determined using a Pierce™ BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA). The proteins were subjected to electrophoresis on a 10–15% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel (SDS‒PAGE) and then transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). The membranes were blocked with 5% skim milk in Tris-buffered saline supplemented with Tween 20 (TBS-T) buffer at room temperature for 1 h and then incubated overnight at 4 °C with the corresponding primary antibodies against the following proteins: PARP1 (Cusabio, 1:1000), PARP3 (Cusabio, 1:1000), TRAF2 (Cusabio, 1:1000), RIPK1 (Cusabio, 1:1000), RIPK3 (Cusabio, 1:500), MLKL (Cusabio, 1:1000), p53 (St John’s Laboratory, 1:1000), Bax (Cell Signaling, 1:1000), BCl2 (Cell Signaling, 1:500), FADD (Cusabio, 1:2000), Caspase-8 (Cusabio, 1:1000), Caspase-9 (Cusabio, 1:1000), Caspase-3 (Cusabio, 1:1000), and GAPDH (St John’s Laboratory, 1:5000). After being washed with TBS-T, the membranes were further incubated for 1 h at room temperature with a horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody (Invitrogen, 1:10000). Proteins were then detected with SuperSignal™ West Pico PLUS Chemiluminescent and visualized with an enhanced ImageQuant™ LAS 4000 mini (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA).

Caspase-3 activity

To evaluate caspase-3 activity, a caspase-3/CPP32 fluorometric assay kit was used according to the manufacturer’s protocol with a DEVD-AFC fluorogenic substrate obtained from intestinal lysates (BioVision, CA, USA). After the tissue and eluted intestinal lysates were washed with buffer k105-100 (BioVision, CA, USA) for 20 min on ice, the intestinal tissue was homogenized to obtain the intestinal lysates. The activity of caspase-3 was then calculated by subtracting the value of Ac-DEVD-AFC with a caspase-3 inhibitor from the value of Ac-DEVD-AFC alone. The emission intensity of the sample was expressed as a percentage of the corresponding value for the appropriate control group.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics are reported in the form of both means and standard deviations or medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs), as appropriate. NEC scoring and apoptosis scoring were performed using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, California, USA) and Student’s t test. The data are presented as the means ± SEMs. The level of significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Evaluation of NEC induction

After laparotomy, compared with the control groups, the full-term NEC and preterm NEC groups both presented significant gross changes in the small intestine. In particular, the preterm NEC group showed significant pneumatosis intestinalis in the whole intestinal wall (Fig. 1a).

After the severity of NEC was evaluated, the NEC scores of the preterm rats in the control group were all grade 1 or 2 by histological analysis. All the rats in the full-term and preterm NEC groups exhibited significant damage to the villi and crypts. However, the NEC scores differed between groups. In particular, the preterm rats in the experimental group had an NEC score of 3.5 ± 0.53, which was significantly greater than that of the preterm control group, which was 0.4 ± 0.52 (p < 0.001) (Table 1). Moreover, the full-term NEC group had an NEC score of 2.3 ± 0.48, whereas the full-term control group had an NEC score of 0.2 ± 0.42. The preterm rats had higher NEC scores than did the full-term rats (p < 0.001) (Fig. 2b).

Representative H&E-stained ileum sections and scoring of NEC grade. (a) Representative pathological assessment of NEC by H&E staining. The NEC score was 0 (full-term control group), 2 (full-term NEC group), 1 (preterm control group), or 3 (preterm NEC group). (b) Summary of the NEC grade distribution, whereby the NEC score increased significantly in the experimental group. Compared with those in the corresponding control groups, the NEC scores in the full-term and preterm NEC groups were significantly greater (***p < 0.001, t tests). Compared with those in the full-term NEC group, the NEC scores in the preterm NEC group were significantly greater (**p < 0.01, t tests).

Evaluation of apoptosis by TUNEL staining

The apoptosis score was estimated by a histological analysis with TUNEL staining (Fig. 3). The apoptosis scores of the full-term rats were 0.5 ± 0.52 in the control group and 1.9 ± 0.73 in the experimental group, which were significantly greater than those of the control group (p = 0.013). The apoptosis scores of preterm rats in the control group were all grade 1 or 2. The percentage of apoptotic cells in the preterm NEC group was 3.0 ± 0.67, which was significantly greater than the corresponding percentage in the control group. The apoptosis scores of preterm rats were greater than those of full-term rats (p < 0.001) (Table 2.).

Representative TUNEL-stained ileum sections and scoring of apoptosis. (a) Examples of apoptosis after TUNEL staining in the NEC group. The NEC score was 0 (full-term control group), 2 (full-term NEC group), 1 (preterm control group), or 3 (preterm NEC group). (b) Summary of the apoptosis score distributions. Compared with those of the full-term NEC group, the NEC apoptosis scores of the full-term NEC group were greater (**p < 0.01, t tests). Compared with those of the preterm NEC group, the NEC apoptosis scores of the preterm NEC group were significantly greater (**p < 0.01, t tests). The scores of the preterm NEC group were significantly greater than those of the full-term NEC group (**p < 0.01).

In the full- and preterm NEC groups, programmed cell death was induced through the regulation of both necroptotic- and apoptotic-related genes

The mRNA levels of necroptosis-related genes (RIPK1, RIPK3, and MLKL) and apoptosis-related genes (TRAF2, p53, Bax, Bcl2, FADD, and RARP1) in the ileum were evaluated by real-time PCR. The results revealed that MLKL gene expression was significantly increased in both the full-term NEC and preterm NEC groups. There were also significant differences in RIPK1 and RIPK3 gene expression levels between the full-term and preterm NEC groups and.

the corresponding control groups. In particular, the expression level of RIPK1 in the preterm NEC group was greater than the corresponding expression levels in the preterm control and full-term NEC groups. These findings suggest that NEC can be induced in preterm rats through RIPK1-dependent necroptosis. The gene expression levels of various apoptosis factors—i.e., TRAF2, p53, Bax, FADD, and RARP1—were increased, but Bcl2 gene expression was not increased in the full-term NEC group. Compared with those in the preterm NEC group, the expression levels of Bax and FADD were significantly increased only in the preterm NEC group (Fig. 4a). These results suggest that the apoptosis pathways may differ between full-term and preterm rats, although NEC was induced in both groups through apoptosis via apoptotic-related genes.

Changes in the gene expression of programmed cell death-related genes. (a) Results from the quantitative real-time PCR of key factors involved in the apoptosis and necrosis pathways, namely, RIPK1, RIPK3, MLKL, TRAF-2, p53, Bax, Bcl2, FADD, and PARP1, in the ileum. All the data are presented as the means ± SEMs (n = 5). ns = not significant, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 compared with each corresponding control group. (b) Relative mRNA expression level of Bax. The ratio of Bax/Bcl-2 was greater in all NEC groups than in the corresponding control groups. The values represent the means ± SEMs (n = 5) for each group. ns = not significant and *p < 0.05 NEC versus control.

The Bcl2 family is well-known as an antiapoptotic factor of the cell death pathway. Thus, we calculated the ratio of Bax/Bcl2 expression levels, because the Bcl2 family mediates the activation of the proapoptotic Bax family. The relative Bax/Bcl2 mRNA level was significantly greater in the full-term NEC group than in the preterm NEC group (Fig. 4b). Therefore, a high level of Bax gene expression can induce the activation of apoptosis in both full- and preterm NEC rats.

In the full-term NEC group, programmed cell death was induced by the activation of p53, Bax, PARP1, and caspase-8, caspase-9, and caspase-3, and the suppression of Bcl2

We performed western blotting analysis of the expression levels of necroptotic- and apoptotic-related proteins and caspases, such as caspase-8, caspase-9, and caspase-3. Compared with those in the control group, the protein levels of TRAF2 and cleaved caspase-8, as well as those of p53, Bax, PARP1, and cleaved caspase-9, and cleaved caspase-3, were significantly greater in the full-term NEC group. The protein level of Bcl2 slightly decreased in the full-term NEC group; however, this difference was not statistically significant (Fig. 5a). The original blots are presented in Supplementary Fig. 1. These results indicate that the antiapoptotic protein Bcl2 cannot suppress the activation of apoptosis in full-term rats.

Changes in protein expression caused by the programmed cell death pathway. Western blot analysis of factors involved in the necrosis pathway—TRAF-2, RIPK1, RIPK3, FADD, MLKL, and caspase-8—and those involved in the apoptosis pathway—p53, Bax, Bcl2, PARP1, PARP3, caspase-9, and caspase-3 protein expression in full-term rats (a) and preterm rats (b) GAPDH expression was used as an internal control. The western blots are representative of three independent experiments. The densitometric intensity data of the proteins from each blot are presented as the means ± SEMs from three independent experiments. ns = not significant, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 compared with each corresponding control group.

In the preterm NEC group, programmed cell death was induced through the activation of RIPK1, TRAF2, FADD, p53, Bax, caspase-8, and caspase-9

Compared with those in the control group, the protein levels of TRAF2, RIPK1, and caspase-8 were increased in the NEC group. The levels of the apoptosis-related proteins p53, Bax, PARP3, and caspase-9 were significantly greater in the preterm NEC group than in the preterm control group, whereas the protein levels of PARP1 were not increased. The level of cleaved caspase-3 was slightly increased in the preterm NEC group. In contrast, the protein level of Bcl2 was increased in the preterm NEC group compared with that in the preterm control group (Fig. 5b). These results suggest that the programmed cell death pathway differed between the full-term and preterm NEC groups, particularly as the protein levels of PARP1 and caspase-3 did not affect the activation of apoptosis in preterm rats. Furthermore, the expression level of Bcl2 was high in the preterm NEC group, which implies that Bax activation might be suppressed by Bcl2 in preterm rats.

Both the full- and preterm NEC groups exhibited induced apoptosis via the activation of Bax

Investigating the protein expression levels of Bax and Bcl2 is important because the Bcl2 family is a critical factor in regulating pro- and antiapoptotic proteins. Therefore, we calculated the ratio of Bax to Bcl2 protein expression based on band intensities in western blot. The relative Bax/Bcl2 ratios at the protein level were greater in both the full- and preterm NEC groups than in the corresponding control groups. However, the ratio of Bax/Bcl2 protein expression was greater in the full-term NEC group than in the preterm NEC group (Fig. 6a). These results suggest that there may be a difference in total Bax levels between preterm and full-term rats, as the expression of Bcl2 can affect the Bax/Bcl2 ratio.

Changes in the protein expression levels of the Bax/Bcl2 ratio, caspase-8, caspase-9, and caspase-3, and the activity of caspase-3. (a) Densitometric intensity data of Bax protein expression. The ratio of Bax/Bcl-2 was significantly greater in all NEC groups than in the corresponding control groups. The values represent the means ± SEMs (n = 5) for each group. *p < 0.05 NEC versus control. (b) Densitometric intensity data of the ratio of cleaved caspase to total caspase expression. Compared with those in the full-term NEC group, the expression levels of all cleaved caspases were significantly increased in the full-term NEC group. In the preterm NEC group, the expression levels of cleaved 8 and 9 were significantly greater than those in the preterm NEC group, but there was no such increase in cleaved caspase-3. All the data are presented as the means ± SEMs from three independent experiments. ns = not significant, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 compared with each corresponding control group. (c) Caspase-3 activity (percent control) in the ileum lysate was significantly greater in the LPS + hypoxia-treated full-term group than in the full-term control group (**p < 0.01). The data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments. ns = not significant, ** P < 0.01 vs. the control group.

The full- and preterm NEC groups presented differences in programmed cell death pathways through the promotion of cleaved caspase-3

We investigated the cleaved-caspase/total caspase ratio, including those of caspase-8, caspase-9, and caspase-3, which are responsible for the activation of necroptosis and apoptosis. For all three caspases, higher levels of the cleaved forms were detected in the full-term NEC group than in the full-term control group. However, cleaved caspase-3 was not increased in the preterm NEC group compared with the preterm control group (Fig. 6b). To further confirm this observation, we conducted a caspase-3 activity assay. Consequently, compared with that of the full-term control group, the emission intensity percentage of the full-term NEC group increased to 41.09%. Moreover, the percent emission intensity of the preterm NEC group did not significantly increase compared with that of the preterm control group, as the latter already had a high level of emission intensity (Fig. 6c). Despite the high emission intensity percentage in the preterm NEC group, we were unsure about the impact of the activation of caspase-3 on the cell death pathway in preterm rats because it was not increased.

Discussion

Studies aiming to investigate the pathogenesis of NEC have attempted to do so using several animal models, including the ischemia‒reperfusion injury, formula feeding, and cold asphyxia stress (FFCAS) models21,22,23,24,25,26. Hypoxia and endotoxins increase the permeability of the intestinal mucosa and the migration of bacteria, and they also induce the activity of polymorphonuclear leukocytes in result to leads the destruction of intestinal mucosa and systemic infection27,28. LPS is a bacterial endotoxin that stimulates an inflammatory response by secreting the platelet-activating factor (PAF) TNF-α. Additionally, LPS can increase the levels of iNOS and NO and promote the apoptosis of enterocytes29,30. In this study, repeated 5% hypoxia and oral administration of LPS (5 mg/kg) were applied to full- and preterm rats to induce NEC, resulting in a significant contribution to the development of a valid NEC rat model similar to the actual clinical situation. Additionally, the TUNEL staining score and caspase-3 activity were both greater in the experimental group than in the control group in both full-term and preterm rats. Consequently, the apoptosis scores were significantly increased in both the full-term NEC and preterm NEC groups, and it was greater in the preterm NEC group than in the full-term NEC group.

The programmed cell death mechanism is activated by caspases, which are common cell death effectors and important factors in chromatin condensation and DNA fragmentation31,32. The apoptosis pathway is known to occur through the Fas/FasL pathway as a cell death receptor and through the Bcl-2/Bax pathway as a mediation pathway of mitochondria, prior to the development of NEC. This signal mediates the activation of proapoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins, such as those in the Bax subfamily, by increasing the outer membrane permeability of mitochondria and stimulating the release of caspase-3 and caspase-9 by increasing the level of cytochrome-C, an apoptotic intermembrane space protein33,34. In contrast, the antiapoptotic Bcl-2 family, such as Bcl-xL or Bcl-2, prevents apoptosis by inhibiting membrane permeability35,36,37. However, our results revealed that Bcl2 expression was decreased in the LPS + hypoxia induced full-term NEC rat model but not in the preterm NEC model. These findings suggest that Bcl2 expression is related to other pathways, including the STAT3 pathway, because STAT3 activation can regulate the expression of Bcl2 proteins38,39. The ratio of Bax/Bcl-2 was significantly reduced by the epidermal growth factor, which has been used as an index of apoptosis stimulation sensitivity40,41,42. In this study, the ratio of Bax/Bcl-2 tended to be slightly greater in the full-term NEC group than in the control group, suggesting that apoptosis.

through the Bax/Bcl-2 pathway may be the primary mechanism of NEC in full-term rats (Fig. 7, left panel). These findings suggest that key mediators of apoptosis could lead to differences in the programmed cell death mechanism between full-term and preterm rats.

Summary of the NEC-induced cell death pathway in full-term and preterm rats. In full-term model rats, FASL-FAS induced pro-caspase-8, which activated caspase-8, caspase-3/7, and PARP1 to promote apoptosis. Furthermore, p53, Bax, and caspase-9 were activated by DNA damage caused by ROS stress. Phosphorylated RIPK3 and MLKL independently induced necrosis. In preterm rats, TNF-α induced apoptosis via caspase-8 activation. TRAF-2, TRADD, RIPK1, FADD, and the pro-caspase-8 family have all been shown to reflect the crosstalk between necrosis and apoptosis via MLKL phosphorylation and the activation of caspase-8, respectively. By inhibiting Bax, Bcl2 overexpression impairs the promotion of Bax and caspase-9.

RIPK1 activation can promote cell death pathways whereby FADD–caspase-8 mediates apoptosis and where RIPK1-independent necroptosis is induced by TNF43,44. In this study, we show that both RIPK1-independent and RIPK1-dependent cell death pathways can promote NEC in full-term and preterm rats (Fig. 7). Prior to birth, RIPK1 activates TNFR-mediated lethality in an ablation of FADD and, caspase-8 mouse model45. Moreover, RIPK3-dependent necrosis is related to RIPK1 functions by blocking RIPK1 inhibitors to induce necroptosis46. Our study is consistent with the previously described role of preterm NEC in promoting necrosis and apoptosis through an RIPK1-dependent pathway in interactions with RIPK3 (Fig. 7, right panel). Strikingly, post birth, RIPK1 is required to prevent RIPK3-dependent lethality to inhibit the recruitment of FADD–caspase-8–FILP related to RIPK1, which cannot promote apoptosis but suppresses RIPK3 function47. Therefore, we could assume that the necroptosis mechanism caused by the activation of RIPK3 was independent of RIPK1 in our full-term rat model (Fig. 7, left panel). However, it remains unclear whether the cell death mechanism is dependent on RIPK1.

Conclusion

The pathophysiology of NEC induced by LPS + hypoxia is associated with programmed cell death pathway. It appears that the apoptotic pathway of the Bax/Bcl-2 system is the main mechanism of NEC in full-term rats. By contrast, several other mechanisms, including TNF-α-induced apoptosis mechanism, may work together to promote NEC development in preterm rats. However, further studies are needed to elucidate the differences in the pathogenesis of NEC development between preterm and full-term rats.

Limitations

In the present NEC rat model, considering the limitations of the animal laboratory, a non-feed group of preterm rats was compared with a group of full-term rats that had been breastfed for 4 days. Recent studies have indicated that early breastfeeding is a protective factor against NEC induction48. Therefore, further investigations are needed to assess the effects of oral intake on NEC induction. In addition, research is needed to examine the maturation of rat intestines induced by stress, steroid injections, and other factors. In this study, corticosteroids may have been released during the surgical procedure to deliver the preterm rats via cesarean section. This could have resulted in a higher rate of NEC induction in preterm rats, as the administered corticosteroids could have accelerated the maturation of preterm rat intestines.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- NEC:

-

necrotizing enterocolitis

- SD:

-

Sprague-Dawley

- LPS:

-

lipopolysaccharide

- RT-PCR:

-

real time PCR

- H&E:

-

hematoxylin & eosin

- TUNEL:

-

terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP-FITC nick-end labeling

- iNOS:

-

Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase

- NO:

-

Nitric oxide

References

Rich, B. S. & Dolgin, S. E. Necrotizing enterocolitis. Pediatr. Rev. 38, 552–559 (2017).

Keefe, G., Jaksic, T. & Neu, J. Necrotizing enterocolitis and short bowel syndrome. Avery’s Dis. Newborn. e4, 930–939 (2024).

Latkowska, M. et al. Gut microbiome and inflammation in response to increasing intermittent hypoxia in the neonatal rat. Pediatr. Res. Adv. Online Publication. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-024-03569-7 (2024).

Wang, F. et al. Targeting cell death pathways in intestinal ischemia-reperfusion injury: a comprehensive review. Cell. Death Discov. 10, 112 (2024).

Neu, J., Chen, M. & Beierle, E. Intestinal innate immunity: how does it relate to the pathogenesis of necrotizing enterocolitis. Semin Pediatr. Surg. 14, 137–144 (2005).

Yang, S. et al. Programmed death of intestinal epithelial cells in neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis: a mini-review. Front. Pediatr. 11, 1199878 (2023).

Yang, J. & Shi, Y. Paneth cell development in the neonatal gut: pathway regulation, development, and relevance to necrotizing enterocolitis. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 11, 1184159 (2023).

Fawley, J. et al. Single-immunoglobulin interleukin-1-Related receptor regulates vulnerability to TLR4-mediated necrotizing enterocolitis in a mouse model. Pediatr. Res. 83, 164–174 (2018).

Tonnus, W. et al. The role of regulated necrosis in endocrine diseases. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 17, 497–510 (2021).

Yuan, J. & Ofengeim, D. A guide to cell death pathways. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. Adv. 25, 379–395 (2024).

Jouan-Lanhouet, S. et al. Necroptosis, in vivo detection in experimental disease models. Semin Cell. Dev. Bio. 35, 2–13 (2014).

Naito, M. G. et al. Sequential activation of necroptosis and apoptosis cooperates to mediate vascular and neural pathology in stroke. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 117, 4959–4970 (2020).

Linkermann, A. et al. Necroptosis in immunity and ischemia-reperfusion injury. Am. J. Transpl. 13, 2797–2804 (2013).

Nagata, S. Apoptosis by death factor. Cell 88, 355–365 (1997).

Waring, P. & Müllbacher, A. Cell death induced by the Fas/Fas ligand pathway and its role in pathology. Immunol. Cell. Biol. 77, 312–317 (1999).

Gupta, S. Molecular signaling in death receptor and mitochondrial pathways of apoptosis (review). Int. J. Oncol. 22, 15–20 (2023).

Lindsten, T. & Thompson, C. B. Cell death in the absence of Bax and Bak. Cell. Death Differ. 13, 1272–1276 (2006).

Pawlowski, J. & Kraft, A. S. Bax-induced apoptotic cell death. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 97, 529–531 (2000).

Hardwick, J. M. & Soane, L. Multiple functions of BCL-2 family proteins. Cold Spring Harb Perspect. Biol. 5, a008722 (2013).

Cory, S. & Adams, J. M. The Bcl2 family: regulators of the cellular life-or-death switch. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2, 647–656 (2002).

Chan, K. L. et al. Revisiting ischemia and reperfusion injury as a possible cause of necrotizing enterocolitis: role of nitric oxide and superoxide dismutase. J. Pediatr. Surg. 37, 828–834 (2023).

Wu, B. et al. Platelet-activating factor promotes mucosal apoptosis via FasL-mediating caspase-9 active pathway in rat small intestine after ischemia-reperfusion. FASEB J. 17, 1156–1158 (2003).

Mendez, Y. S., Khan, F. A., Perrier, G. V. & Radulescu, A. Animal models of necrotizing enterocolitis. World J. Pediatr. Surg. 25, e000109 (2020).

Jilling, T., Lu, J., Jackson, M. & Caplan, M. S. Intestinal epithelial apoptosis initiates gross bowel necrosis in an experimental rat model of neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis. Pediatr. Res. 55, 622–629 (2004).

Zani, A. et al. Assessment of a neonatal rat model of necrotizing enterocolitis. Eur. J. Pediatr. Surg. 18, 423–426 (2008).

Lee, Y. S., Jun, Y. H. & Lee, J. Oral administration of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells attenuates intestinal injury in necrotizing enterocolitis. Clin. Exp. Pediatr. 67, 152–160 (2024).

Colgan, S. P., Campbell, E. L. & Kominsky, D. J. Hypoxia and mucosal inflammation. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 11, 77–100 (2016).

Forsythe, R. M., Xu, D. Z., Lu, Q. & Deitch, E. A. Lipopolysaccharide-induced enterocyte-derived nitric oxide induces intestinal monolayer permeability in an autocrine fashion. Shock 17, 180–184 (2002).

Hunter, C. J. & De Plaen, I. G. Inflammatory signaling in NEC: role of NF-κB, cytokines and other inflammatory mediators. Pathophysiology 21, 55–65 (2014).

Chokshi, N. K. et al. The role of nitric oxide in intestinal epithelial injury and restitution in neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis. Semin Perinatol. 32, 92–99 (2008).

Jänicke, R. U., Sprengart, M. L., Wati, M. R. & Porter, A. G. Caspase-3 is required for DNA fragmentation and morphological changes associated with apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 9357–9360 (1998).

Kumar, S., Dorstyn, L. & Lim, Y. The role of caspases as executioners of apoptosis. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 50, 33–45 (2022).

Kiraz, Y., Adan, A., Kartal Yandim, M. & Baran, Y. Major apoptotic mechanisms and genes involved in apoptosis. Tumour Biol. 37, 8471–8486 (2016).

Shoshan-Barmatz, V., Arif, T. & Shteinfer-Kuzmine, A. Apoptotic proteins with non-apoptotic activity: expression and function in cancer. Apoptosis 28, 730–753 (2023).

Breckenridge, D. G., Germain, M., Mathai, J. P. & Nguyen, M. Shore. G.C. Regulation of apoptosis by endoplasmic reticulum pathways. Oncogene 22, 8608–8618 (2003).

Wang, W., Song, J., Lu, N., Yan, J. & Chen, G. Sanghuangporus Sanghuang extract inhibits the proliferation and invasion of lung cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. Nutr. Res. Pract. 17, 1070–1083 (2023).

Vanasse, G. J. et al. Bcl-2 overexpression leads to increases in suppressor of cytokine signaling-3 expression in B cells and de novo follicular lymphoma. Mol. Cancer Res. 2, 620–631 (2004).

Bhattacharya, S., Ray, R. M. & Johnson, L. R. STAT3-mediated transcription of Bcl-2, Mcl-1 and c-IAP2 prevents apoptosis in polyamine-depleted cells. Biochem. J. 392, 335–344 (2005).

Wu, D. & Wang, Z. Gastric Cancer cell-derived Kynurenines Hyperactive Regulatory T Cells to promote Chemoresistance via the IL-10/STAT3/BCL2 signaling pathway. DNA Cell Biol. 41, 447–455 (2022).

Hosny, G., Ismail, W., Makboul, R., Badary, F. A. M. & Sotouhy, T. M. M. Increased glomerular Bax/Bcl2 ratio is positively correlated with glomerular sclerosis in lupus nephritis. Pathophysiology 25, 83–88 (2018).

Azimian, H., Dayyani, M., Toossi, M. T. B. & Mahmoudi, M. Bax/Bcl-2 expression ratio in prediction of response to breast cancer radiotherapy. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 21, 325–332 (2018).

Wang, Y. et al. Catalpol prevents denervated muscular atrophy related to the inhibition of autophagy and reduces BAX/BCL2 ratio via mTOR pathway. Drug Des. Devel Ther. 3, 243–253 (2018).

Degterev, A. et al. Identification of RIP1 kinase as a specific cellular target of necrostatins. Nat. Chem. Biol. 4, 313–321 (2008).

Dillon, C. P. et al. RIPK1 blocks early postnatal lethality mediated by caspase-8 and RIPK3. Cell 157, 1189–1202 (2014).

Zhang, H. et al. Functional complementation between FADD and RIP1 in embryos and lymphocytes. Nature 471, 373–376 (2011).

Li, J. et al. The RIP1/RIP3 necrosome forms a functional amyloid signaling complex required for programmed necrosis. Cell 150, 339–350 (2012).

Green, D. R., Oberst, A., Dillon, C. P., Weinlich, R. & Salvesen, G. S. RIPK-dependent necrosis and its regulation by caspases: a mystery in five acts. Mol. Cell. 44, 9–16 (2011).

Sisk, P. M. et al. Early human milk feeding is associated with a lower risk of necrotizing enterocolitis in very low birth weight infants. J. Perinatol. 27, 428–433 (2007).

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by KT&G Grant-in-Aid for neonatal research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HYK and SYK suggested the main idea for animal experimentation. HRL, DYK and KYL carried out the animal experiment and contributed to sample preparation. HRL and KYL analyzed the histological examination. HRL and DYK was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. JKY and HBY provided critical feedback and helped shape the research, analysis and manuscript. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript. HYK supervised the project.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the applicable animal welfare regulations and with the approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC #08–0069) of Seoul National University Hospital. All applicable international, national, and/or institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals were followed.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, Hr., Ko, D., Lee, K.Y. et al. Comparison of necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC)-related apoptosis factors between preterm and full-term rats. Sci Rep 15, 25763 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86506-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86506-w