Abstract

Selective lithium recovery from a mixture of LFP-NMC spent lithium batteries presents significant challenges due to differing structures and elemental compositions of the batteries. These differences necessitate a distinct recycling pathway for each, complicating the process for the mixture. This study explored a carbothermal reduction approach combined with water leaching under atmospheric conditions to achieve a selective lithium recovery. For individual NMC black mass, at the optimal carbothermal conditions (950 °C, 15 °C/min, 2 h), lithium recovery of 95.7 ± 0.31% with 100% selectivity could be achieved. However, when the black mass was mixed with that of LFP in a 50:50 ratio, the recovery dropped to 9.78 ± 0.44%. Solid-state reactions during carbothermal process resulted in the formation of highly insoluble Li3PO4, and Fe-Ni-Co/Ni-Co alloys, which hinder lithium dissolution. To address these challenges, Na2CO3 was introduced as an additive to suppress Li3PO4. The addition of Na2CO3 to the 50:50 ratio of LFP-NMC black mass, increased lithium recovery to 59.47% with 100% selectivity. This enhancement was due to the stabilization of lithium as Li2CO3, a water-soluble compound. The results demonstrated that addition of Na2CO3 is a promising strategy for improving lithium recovery from mixed LFP-NMC batteries, providing a potential pathway for a more efficient recycling process.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Electrification of vehicles is one of vital strategies in meeting net-zero emission (NZE) targets and addressing global climate change issues1,2. By replacing conventional internal combustion engine vehicles with electric-powered alternatives, it is expected that greenhouse emissions can be significantly reduced to reach a cleaner and more sustainable transportation. Lithium-ion batteries currently serve as the primary energy storage solution due to their high energy density, reliability and efficiency3,4.

Currently, two types of lithium-ions batteries (LIBs) are dominating the global electric vehicle (EV) market, including nickel-manganese-cobalt (NMC) and lithium iron phosphate (LFP) batteries5,6. NMC batteries are known for their high energy density, which is ideal for long range EVs. Meanwhile, LFP batteries provide superior safety and stability, particularly for shorter-range and more cost-efficient applications5. As the EV market continuously expands, a huge volume of spent batteries is expected to accumulate in the near future. It is predicted that the amount of spent LIBs will reach over 11 million tonnes by 2030. This would highlight a critical need for efficient battery recycling methods. Battery recycling is critical not only for reducing waste, recovering valuable materials and minimizing the environmental impacts associated with battery disposal, but also ensuring the circular economy aspect of lithium-ion battery applications .

Effective recycling routes are essential because different types of spent lithium-ion batteries might require optimized approaches for material recovery7. Currently, industrial recycling technology primarily focuses on nickel-cobalt-based batteries such as NMC due to the high economic value of lithium, nickel and cobalt1,7. However, this process typically relies on strong acids for metal extraction and a lot of other chemicals which pose environmental risks and involve complex waste management. More sustainable alternative technologies have been explored to offer a more environmentally friendly approach to recycle the batteries, including lithium recovery from NMC type batteries using water as an extraction agent1,8. A thermal treatment followed by water leaching has been reported to selectively leach lithium from the black mass of NMC batteries1.

As NMC and LFP batteries are widely deployed, mixed streams of spent batteries are increasingly likely in the recycling process. The mixture would present challenges, as their differing compositions might complicate the extraction process and reduce recovery efficiency. Some studies have explored acid leaching methods to manage mixed spent LFP-NMC batteries9,10, but the leachate could unselectively leach all metals from the cathode material, which requires further complex separation and purification process. Therefore, this approach still raises environmental concerns and may not be fully efficient for real applications. Another approach to selectively leach lithium from NMC type black mass has been reported that used water under CO2 supercritical condition as a leaching media11. Unlike the other traditional battery recycling approaches, this process could recover lithium earlier in the process and therefore maintain its high recovery rate. However, the process requires high temperature 230 °C and pressure 100 bar that might become a concern for further real application11.

The selective recovery of lithium from the black mass of mixed NMC and LFP batteries has not been previously reported. This study investigates the effect of LFP composition in the black mass on the selective recovery of lithium through water leaching under atmospheric conditions. The findings aim to advance efficient and sustainable recycling methods for mixed NMC and LFP batteries. While most studies on lithium-ion battery recycling focus on individual chemistries such as NMC or LFP, these methods often involve high environmental costs, complex processes, or extreme conditions. However, the rapid growth of the electric vehicle market and the inevitable accumulation of mixed streams of NMC and LFP batteries highlight an urgent need for efficient, environmentally friendly, and scalable recycling methods tailored to these mixed chemistries.

The present study is the first to systematically investigate the selective recovery of lithium from mixed NMC-LFP black mass using a simple water leaching approach under atmospheric conditions. By examining the influence of LFP composition in mixed battery streams on lithium recovery efficiency, this work pioneers a sustainable and low-chemical alternative to conventional recycling processes. These findings provide critical insights into optimizing the recycling of mixed battery chemistries, contributing to the advancement of circular economy principles in the lithium-ion battery industry and addressing the challenges posed by the increasing diversity of spent battery materials.

Methodology

Materials

The cathodes of spent NMC-532 batteries and used LFP batteries (sourced from local spent battery collectors) were used as the main raw materials for the mixed battery recycling experiment. The results of elemental characterization are presented in Table 1. Deionized water (Onelab Water One, PT. Jaya Medica Industri) was used in the water leaching process. For elemental analysis, the solid residue was dissolved using 37% hydrochloric acid (HCl, EMSURE for analysis, Merck Millipore) and 30% hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), EMSURE for analysis, Merck Millipore).

Method

Raw materials used in this experiment were black mass from spent NMC-532 and LFP batteries. The spent batteries were pretreated by discharging them in a 2 M NaCl solution for 24 h. After discharging, the batteries were dismantled to separate their components. The anode and cathode current collectors were retrieved, and their active powders were separated to obtain the black mass for each battery. Black mass consists of active black powder components derived from the cathode and anode sheets. Table 1 presents the elemental composition and quantities of cathodes and anodes obtained from a single 18,650 battery cell.

The carbothermal process was performed on black mass from NMC-532 batteries and mixed batteries composed of NMC-532 and LFP. The carbothermal experiment for NMC-532 batteries involved temperature variations of 750 °C, 850 °C, and 950 °C, along with heating rates of 5 °C/min, 10 °C/min, and 15 °C/min. To study the effect of LFP battery composition on the carbothermal process, the black mass composition from LFP batteries relative to NMC-532 was varied. Mixed batteries were prepared with LFP/NMC-532 black mass ratios of 0:100, 10:90, 20:80, 30:70, 50:50, and 100:0. The study also investigated variations in the carbothermal operating temperature for mixed batteries at 750 °C, 850 °C, and 950 °C.

The mixed black mass was prepared by combining black mass sourced from NMC-532 and LFP batteries. The mixing process was performed using a powder mixer (VH-2 Powder Mixer, Jingzhou) for 1 h at a rotation speed of 100 rpm to achieve a relatively homogeneous mixture. For the carbothermal process, 10.0000 g of the mixed black mass were placed into a 30 mL crucible. The cathode-to-anode ratios were 72.54%:27.46% for NMC and 69.53%:30.47% for LFP. The crucible was sealed tightly to maintain oxygen-free conditions. The carbothermal process was conducted using a furnace (RHF 1600, Carbolite) at a constant temperature for 2 h.

After the carbothermal process, 4.0000 g of black mass were taken for water leaching process. The leaching was used to evaluate lithium recovery and selectivity, the key parameters for assessing process efficiency. The process was conducted at an S/L ratio of 40 g/L, a temperature of 60 °C, and a stirring speed of 500 rpm for one hour. The leaching process was performed in a three-neck flask reactor (Pyrex) equipped with a stirring motor (RW 20 digital, IKA ) and a reflux condenser to condense the vapor. The reactor was heated using a water bath (Analog Bath EOK-200, As One) controlled by a thermostat to maintain a constant temperature. The solid residue was separated from the filtrate using a vacuum filter (RV5, Edwards) and then dried in an oven (Digital Drying Oven OV-30, B-One) at 110 °C for 2 h. The filtrate and residue were analyzed for elemental content to determine lithium recovery and selectivity.

Characterization

Carbothermal treatment was examined through thermogravimetric, compounds, and elemental characterization to understand the mechanisms and phenomena occurring during the process. The elemental composition of the raw materials and post-carbothermal black mass was analyzed using Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectroscopy (ICP-OES Optima 8300, PerkinElmer). The phases and components composition was analyzed using X-ray diffraction (XRD PANalytical Empyrean, Malvern) with a scanning rate of 0.0234°/s over a range of 5°–90°. Surface morphology and elemental distribution were observed using Scanning Electron Microscope-Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (SEM-EDX JSM-IT200, JEOL) at 900x magnification. Functional groups of the compounds were analyzed using a Raman spectrometer (UV-vis-NIR Dispersive Micro Confocal Hyperspectral Raman Imaging Spectrometer, Horiba). The instrument was set to 50x magnification with a 532 nm laser, 1800 grating, 25% ND filter, and a 10-second acquisition time. Thermogravimetric analysis was performed using Simultaneous Thermal Analysis (STA 449 F3 Jupiter, Netzsch) with a heating rate of 5 K/min from 30 °C to 1200 °C to study mass and heat evolution during the carbothermal process. The elemental composition of filtrate samples from the water leaching process was analyzed using ICP-OES. Solid residue samples from the leaching process were digested before elemental analysis. A 0.1-gram solid sample was digested with 5 mL of 37% hydrochloric acid and 1 mL of 30% hydrogen peroxide for 24 h to ensure complete dissolution.

Result and discussion

Carbothermal reduction of NMC

Carbothermal reduction is a common method for reducing metal oxides into metals or lower oxidation state compounds using carbon sources like coke, coal, or graphite12,13. This process involves high temperatures to break the oxide structure. In battery recycling, this is advantageous as it liberates lithium from bonds with nickel, cobalt, and manganese oxides. Once freed, lithium is more readily extractable through hydrometallurgical processes. Additionally, as an alkali metal, lithium in its oxidized form is significantly more water-soluble than the transition metal oxides in the battery cathode13,14.

The breakdown of the metal oxide structure occurs when oxygen atoms are removed through a reaction with carbon, producing carbon monoxide, as shown in Eq. (1). In the next stage, the unstable carbon monoxide further reduces the metal oxide by removing additional oxygen, forming stable carbon dioxide, as Eq. (2). This reduction process is most efficient at high temperatures in an inert (oxygen-free) atmosphere. The potential overall reactions involved in the carbothermal reduction of NMC-532 are outlined in Eq. (3).

The carbothermal reduction of NMC-532 begins at 710 °C, as evidenced by the evolution of mass (TG) and energy (DCS) in Fig. 1a as well as shifts in the mass gradient (dTG) and energy gradient (dDSC) in Fig. 1b. In thermogravimetric analysis, dTG and dDSC provide detailed insights into mass and energy changes over time15. The dDSC plot confirms an exothermic reaction, aligning with the typical characteristics of a carbothermal reduction reaction. Meanwhile, the dTG curve shows the effect of temperature on the mass loss rate of the NMC black mass, with a significant decline at 769.5 °C indicating decomposition and mass loss due to the reduction reaction between NMC-532 and carbon, which produces CO2 gas. This mass loss corresponds to the gradual removal of oxygen atoms from the NMC structure, although the reduction is partial at this stage. A sharp negative peak at 861.6 °C in the dTG curve suggests more extensive metal reduction, further supported by an intense energy spike in the DSC curve at 866.5 °C, which reflects an intense exothermic reaction. These observations indicate that the optimal carbothermal reduction occurs within this temperature range.

In battery recycling, optimal carbothermal conditions can convert lithium compounds in the black mass into water-soluble forms that promote selective and complete lithium leaching. The recovery of lithium in the leaching process is influenced by the solubility of the lithium compounds formed during the process16. Lithium can exist in three forms: Li2CO3, Li2O, and metallic Li. At 25 °C, Li2CO3 has a solubility of 1.29 g/100 mL, while Li2O is highly soluble at 201.3 g/100 mL, and metallic Li reacts directly with water17,18. Above 718 °C, Li2CO3 becomes thermodynamically unstable and decomposes into Li2O19. This study employed temperatures exceeding this threshold to enhance lithium recovery through water leaching. Additionally, the impact of the heating rate was assessed, as it likely plays a critical role in optimizing lithium recovery efficiency.

Figure 2a shows that the heating rate during the carbothermal process has a significant impact on lithium recovery via water leaching. The recovery decreases as the heating rate increases. At heating rates of 5 °C/min, 10 °C/min, and 15 °C/min, the lithium recoveries were 92.06 ± 0.42%, 89.9 ± 0.78%, and 85.49 ± 0.89%, respectively. Higher heating rates lead to uneven temperature distribution within particles, which disrupts the uniformity of the reduction reaction. This often results in heterogeneous products containing residual lithium compounds that are poorly soluble. Furthermore, rapid heating may cause CO2 gas to accumulate on reactive surfaces, which inhibits the interaction between carbon and lithium. In contrast, lower heating rates provide sufficient time for atomic migration to reach a more complete reduction. At the operating temperature, the stable lithium phase is Li2O, which is highly water-soluble. Consequently, lower heating rates significantly lead to higher lithium recovery.

In addition to the heating rate, the target temperature is another critical factor in the carbothermal reduction process. As shown in Fig. 2b, increasing temperature leads to decreased lithium recovery during leaching. Lithium recoveries at 750 °C, 850 °C, and 950 °C are 95.7 ± 0.31%, 94.32 ± 0.49%, and 85.49 ± 0.89%, respectively. Although thermogravimetric analysis in Fig. 1 indicates that higher temperatures enhance metal reduction, lithium recovery decreases at elevated temperatures due to the incorporation of lithium into the Ni-Co alloy phase formed at these temperatures. Thermodynamic analysis using the Ellingham diagram indicates that the oxides of nickel and cobalt reduce to their metallic forms at 429.1 °C and 478.8 °C, respectively20,21. The Ni-Co alloy can trap lithium within its structure, hindering extraction during leaching. XRD results in Fig. 3 confirm the presence of this alloy phase. These findings highlight the importance of optimizing the target temperature to maximize lithium recovery while minimizing the formation of Ni-Co alloy.

The XRD analysis in Fig. 3 reveals complex transformations in the NMC black mass during carbothermal reduction. The NMC-532 cathode undergoes partial reduction, with some elements fully reduced to metals or alloys, while the others remain as lower oxidation state metal oxides. In the cathode, metals are initially present in oxidized states such as Li+1, Ni2+/Ni3+, Co3+, and Mn4+22,23. During carbothermal process, transition metals like Ni, Co, and Mn are reduced, while lithium reacts with CO2 to form Li2CO3. A portion of Li2CO3 thermally decomposes into Li2O. The XRD results confirm that lithium compounds are primarily present as Li2CO3, with smaller amounts as Li2O. Nickel and cobalt are fully reduced and form a Ni-Co alloy, whereas manganese is partially reduced and remains as MnO. These findings align with the proposed reaction pathways detailed in Eqs. (4–7). Additionally, during the carbothermal treatment of NMC batteries, not only does metal reduction occur, but also the decomposition of organic compounds such as PVDF. PVDF is a crystalline polymer with a high decomposition temperature of approximately 497.7 °C24. Therefore, the XRD peaks of α-PVDF at 18.63° (020) and 19.34° (110)25,26 observed in the raw material disappear in the post-carbothermal NMC black mass, as shown in Fig. 3.

The reduction of nickel and cobalt compounds from the NMC-532 cathode is characterized by the formation of alloys, as indicated by XRD 2θ peaks at 44.5° (111), 51.8° (200), and 76.4° (220)27. Unlike nickel and cobalt, manganese only reaches to the + 2 oxidation state, forming MnO, as evidenced by XRD 2θ peaks at 34.9° (111), 40.6° (200), 58.8° (220), 70.4° (311), and 74.0° (222)28. Lithium, on the other hand, is predominantly found in the Li2CO3 phase, with a smaller fraction detected as Li2O. This indicates that the decomposition of Li2CO3 into Li2O is incomplete. The incomplete decomposition is likely hindered by the extensive formation of Ni-Co alloy, which cause surface passivation and obstruct the mass transfer of CO2 released during decomposition. As a result, Li2CO3 remains within the alloy structure, preventing further decomposition. This hypothesis is supported by XRD data showing that the intensity of Li2O peaks does not significantly increase, even as the temperature is raised from 750 °C to 950 °C, despite the onset of Li2CO3 decomposition at 718 °C19. Furthermore, at higher temperatures, the formation of alloys becomes more pronounced, exacerbating the entrapment of Li2CO3 and further hindering its decomposition due to increased mass transfer resistance.

The carbothermal reduction of NMC produces hard-textured agglomerated solids, as shown in Fig. 5. The agglomerates may form because the Ni-Co alloy acts as a binding matrix, aggregating surrounding particles. SEM-EDS analysis in Fig. 4 reveals a uniform distribution of Ni and Co elements throughout the solid particles. This indicates that the Ni-Co matrix spreads and adheres to other particles, forming a cohesive and hard structure. Figure 4 further shows the co-distribution of C and O elements within the solid, suggesting the presence of Li2CO3 with characteristic C–O bonds. In conventional metal oxide reduction processes, C and O elements combine into CO or CO2 gases which then leave the system. However, during the carbothermal reduction of NMC, CO2 reacts with lithium to form Li2CO3, which stabilizes in the solid phase, as shown in Eq. (7). Therefore, the significant presence of C and O elements in the solid particles, as shown in Fig. 4, results from the reaction between CO2 and lithium, forming stable Li2CO3, rather than escaping as a gaseous phase.

The relatively well-dispersed Li2CO3 throughout the solid indicates that the reaction between lithium and CO2 to form Li2CO3 occurs across the entire solid matrix. This is confirmed by Raman spectroscopy analysis performed on multiple points of the solid samples, labeled as regions A to E in Fig. 5, all of which consistently exhibit the presence of Li2CO3. The characteristic Raman shifts for Li2CO3 include peaks at 119.08 cm−1, 148.33 cm−1, and 184.75 cm−1, serving as fingerprints of Li2CO329, corresponding to the vibrational modes of Li–CO3 bonds in Li2CO330. Additional Raman peaks provide further insight into the vibrational behavior of CO3. Peaks at 264.37 cm−1 represent out-of-plane bending vibrations of CO3, while those at 368.25 cm−1 and 423.27 cm−1 correspond to in-plane bending vibrations (ν2) of CO330. Peaks observed at 701.92 cm−1 and 737.83 cm−1 are attributed to in-plane bending modes (ν4) of CO3, and the peak at 1082.43 cm−1 is associated with the symmetric stretching mode (ν1) of CO330. Finally, peaks at 1404.04 cm−1 and 1451.12 cm−1 are indicative of the asymmetric stretching modes (ν3) of CO331.

In addition to Li2CO3, the presence of MnO in the black mass following carbothermal reduction of NMC is confirmed by Raman spectra, which exhibit characteristic shifts at ν2 (348.41 cm−1), ν3 (401.37 cm−1), ν4 (554.71 cm−1), and ν5 (646.14 cm−1)32. The Raman shift at 554.71 cm−1 corresponds to the asymmetric stretching of Mn–O bonds, while the peak at 646.14 cm−1 represents a higher-order vibrational mode32. Additionally, phenomena such as peak shifting and overlapping are observed in the symmetric stretching vibration (401.37 cm−1) and the symmetric out-of-plane bending vibration (348.41 cm−1). The shift in the vibrational model of MnO is caused by the interference from the vibration mode of Li2CO3 at a relatively close proximity. This interaction leads to the formation of hybrid vibrational characteristics. Such hybrid modes may arise due to interactions between Li2CO3 and MnO within the solid matrix, particularly during high-temperature reactions followed by a temperature quenching. Additionally, the Ni–Co alloy phase present in the system may hinder diffusion and reactions within the solid particles, promoting the formation of possible transitional phases. This hybrid vibrational characteristic is evident in the altered symmetric stretching and bending vibrations, representing a combination of MnO and Li2CO3 vibrational modes. The transitional phase formed by this interaction is characterized by a low water solubility during water leaching, which may contribute to a reduced lithium recovery. Furthermore, the extent of this Li2CO3-MnO transitional state is expected to increase when alloy formation becomes extensive, further worsening the decrease of lithium recovery.

Carbothermal reduction of mixed LFP-NMC

Carbothermal reduction process applied to NMC battery cathodes has demonstrated high efficiency in lithium extraction, achieving 100% selectivity and a recovery rate of over 85% using only water. The primary advantage of this process is its ability to extract lithium at the early stage of the battery recycling process without the need for additional reagents during the leaching process. Building on this success, the same approach could be tested for a mixture of NMC and LFP batteries, which are currently prevalent in electric vehicles. Processing mixed LFP-NMC batteries represents a significant challenge for future battery recycling, particularly when unidentified batteries are intermixed.

The carbothermal reduction applied to mixed black mass is expected to disrupt the structures of both NMC and LFP, enabling a selective lithium extraction during water leaching with a high recovery rate. Thermogravimetric analysis (STA) results, as shown in Fig. 6a–c, reveal significant mass changes during the carbothermal reduction of mixed LFP-NMC black mass, indicating potential reactions or structural and phase transformations in the solid materials. Additionally, the DSC profile in Fig. 6a shows exothermic energy changes, particularly at elevated temperatures, suggesting energy release due to structural changes or material decomposition.

However, the mass and energy changes observed during carbothermal reduction of mixed LFP-NMC black mass show a significant difference from those of individual NMC or LFP batteries. This is evident from the dTG profiles in Fig. 6c and the DSC-dDSC profiles in Fig. 6d. The dTG profiles for NMC, LFP, and mixed LFP-NMC systems show a sharp mass change peak at 98 °C, attributed to water evaporation from the solid system. The dTG peak at 269 °C corresponds to the decomposition of volatile components, such as the electrolyte used in lithium batteries. Additionally, peaks within the 460–650 °C range are associated with the decomposition of the PVDF binder present in the batteries24. Below 650 °C, the dTG and dDSC profiles for NMC, LFP, and mixed LFP-NMC batteries exhibit similar patterns, indicating that the carbothermal reduction process for all battery types involves similar water evaporation, volatile matter decomposition, and PVDF binder decomposition. However, above 650 °C distinct phenomena are observed for NMC, LFP, and mixed LFP-NMC batteries. These significant differences in the mass and energy change profiles highlight variations in the underlying mechanisms and the compounds or phases formed for each battery type.

Based on Fig. 6c,d, the dTG and DSC/dDSC profiles for the mixed LFP-NMC black mass exhibit significant differences compared to those observed during the carbothermal reduction of individual NMC and LFP black masses. This indicates potential interactions between NMC and LFP components during the carbothermal process. As a result, the reaction mechanism deviates from that of each battery type processed independently. These interactions and resulting reactions lead to distinct characteristics in the final product compounds or phases. Consequently, the characteristics of the formed phases are likely to influence the lithium recovery rate and selectivity during the water leaching process.

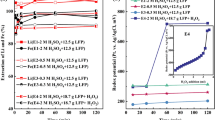

This study examines the effect of LFP content in the mixed batteries on carbothermal reduction and its impact on the lithium recovery during water leaching process. Experimental results show a decline in lithium recovery as the proportion of LFP in the mixed black mass increases. Figure 7a demonstrates that a higher LFP/NMC ratio leads to a significant reduction in lithium recovery in the water leaching. This suggests that the proportion of water-insoluble lithium compounds in the carbothermal products of mixed LFP/NMC increases as the LFP content rises. The decline in lithium recovery is more pronounced in the black mass of the LFP-NMC mixture subjected to carbothermal reduction at 950 °C. In the absence of LFP in the black mass mixture, lithium recovery can reach up to 85.49 ± 0.89%. However, with the addition of 10%, 20%, 30%, and 50% LFP, lithium recovery decreases to 79.35 ± 1.62%, 61.89 ± 2.40%, 34.50 ± 2.49%, and 9.78 ± 0.44%, respectively.

Variations in processing temperature have a minimal impact on the lithium recovery. As shown in Fig. 7b, operating temperatures of 750 °C, 850 °C, and 950 °C result in lithium recoveries of 16.17 ± 1.06%, 14.11 ± 0.35%, and 9.78 ± 0.44%, respectively. These findings suggest that the challenges in the carbothermal reduction of mixed LFP-NMC batteries arise not from the operating conditions but from reactions of components in the mixed black mass that lead to the formation of water-insoluble lithium compounds. This phenomenon is likely driven by specific interactions between NMC and LFP, which trap lithium in compounds that resist dissolution during the water leaching process.

The formation of water-insoluble lithium compounds during the carbothermal reduction of mixed LFP-NMC battery black mass was confirmed through XRD analysis. As shown in Fig. 8, phase analysis indicates that the majority of lithium is present as lithium phosphate (Li3PO4). Several peaks corresponding to Li3PO4 were identified, including 2θ positions at 22.36° (110), 33.94° (210), 43.66° (221), 49.48° (310), 54.64° (222), and 51.03° (400)33. Lithium phosphate (Li3PO4) is characterized by its low solubility in water, with values of only 140.517 mg Li/L at 90 °C and 287.931 mg Li/L at 30 °C34. In contrast, lithium carbonate (Li2CO3) is significantly more soluble, with a solubility of 2423.54 mg Li/L at 25 °C35—approximately eight times higher than that of Li3PO4. The low solubility of Li3PO4 substantially reduces the efficiency of the water leaching process, resulting in lower lithium recovery rates. The formation of Li3PO4 during the carbothermal reduction of mixed batteries becomes more pronounced as the proportion of LFP in the black mass increases. This is attributed to the higher concentration of PO4³⁻ ions in the system, which enhances the formation of Li3PO4 through increased interaction and reaction, as described by Eq. (8). This interaction highlights the significant impact of LFP content on the challenges associated with lithium recovery in LFP-NMC mixed battery recycling.

The extensive formation of Li3PO4 was further confirmed by element mapping using SEM-EDS. While lithium itself is undetectable, mapping of phosphorus (P) and oxygen (O) effectively illustrates the distribution of Li3PO4 in the solid products of carbothermal reduction. As shown in Fig. 9, the co-localization of phosphorus and oxygen suggests the presence of compounds containing P–O bonds. Potential compounds with P–O bonds include metal phosphates such as Li3PO4, Ni3(PO4)2, Co3(PO4)3, Mn3(PO4)3, FePO4, and LiFePO4. However, the distinct spatial distribution of metals such as Fe, Ni, Mn, and Co compared to P–O confirms that Li3PO4 is the predominant compound formed. This conclusion is strongly supported by EDS, XRD, and Raman spectroscopy analyses. As shown in Fig. 10 (Spot 1 and 3), Raman spectrum of Li3PO4 is characterized by peaks at 155.45 cm−1 and 217.12 cm−1, corresponding to external lattice vibration modes (ν5) between lithium and phosphate (PO4)36. Additional characteristic peaks include 383.08 cm−1 (bending mode vibration O–P–O, ν2), 622.12 cm−1 (bending mode vibration O–P–O, ν4), 949.30 cm−1 (symmetric stretching P–O, ν1), and 1020.71 cm−1 and 1060.44 cm−1 (asymmetric stretching P–O, ν3)36. Based on this combined evidence from SEM-EDS mapping, XRD phase analysis, and Raman spectroscopy, it can be conclusively determined that the low lithium recovery during water leaching is primarily due to the formation of Li3PO4, a compound with extremely low water solubility.

In addition to the formation of water-insoluble Li3PO4, lithium dissolution is further hindered by its entrapment within the matrix of Fe-Ni-Co and Ni-Co alloys, which are formed extensively during the carbothermal reduction process. Thermodynamic analysis indicates that the reduction of CoO, NiO, and FeO to their respective metals using carbon occurs at minimum temperatures of 478.8 °C, 429.1 °C, and 745.1 °C, respectively13,37. These reduction temperatures are significantly lower than the experimental temperature range of 750–950 °C, making the formation of these alloys in the solid system highly favorable. XRD analysis, as presented in Fig. 8, confirms the presence of Fe-Ni-Co and Ni-Co alloys, with characteristic 2θ peaks detected at 41.61° (Ni-Co), 43.66° (γ Fe-Ni-Co), 44.57° (α Fe-Ni-Co or Ni-Co), 51.89° (Fe-Ni-Co or Ni-Co), 47.63° (Ni-Co), and 62.62° (Ni-Co)27,38. Additionally, low-valence transition metal oxides, such as FeO, are identified with 2θ peaks at 42.66° (200), 58.91° (220), and 72.49° (311)39, indicating that the reduction of FeO to metallic Fe is incomplete. This is likely due to the higher reduction temperature required for Fe compared to Ni and Co. Consequently, Ni and Co are primarily observed in their metallic forms, while Fe is present as a combination of metallic Fe, FeO, and LiFePO4. These findings emphasize that lithium recovery is limited not only by the formation of insoluble Li3PO4 but also by the entrapment of lithium within the alloy matrix and the incomplete reduction of Fe-containing phases. Together, these factors present significant challenges to achieving high lithium recovery during water leaching step.

In the carbothermal process, manganese is the only transition metal that does not undergo complete reduction to its metallic state. Instead, it is partially reduced to MnO in both NMC and mixed NMC-LFP systems due to the insufficient operating temperature. Thermodynamically, the complete reduction of MnO to metallic Mn requires a minimum temperature of 1332.9 °C13. XRD analysis, shown in Fig. 10, confirms the presence of MnO with peaks at 2θ values of 35.12° (111), 40.64° (200), and 58.68° (222)28. Raman spectra further validate this observation, with peaks at 310.40 cm−1 and 361.61 cm−1 indicating bending mode vibrations (ν4) and a peak at 648.19 cm−1 corresponding to symmetric stretching vibrations of Mn-O (ν1)32, as seen in Spot 2 of Fig. 10. These results confirm that manganese in NMC and mixed NMC-LFP black mass undergoes partial reduction from a + 4 oxidation state to MnO with a + 2 state. Additionally, in mixed battery systems, residual graphite is observed in the black mass post-carbothermal process, indicating incomplete combustion to CO or CO2, as evidenced in the Raman spectra at Spot 4 of Fig. 10.

Solution for recycling LFP-NMC mixed batteries

As previously mentioned, the presence of LFP in the LFP-NMC mixed black mass significantly reduced lithium recovery during water leaching. During the carbothermal process conducted prior to water leaching, the presence of phosphate compounds from LFP led to the formation of lithium phosphate, which has low water solubility. Therefore, in this work, carbonate compounds were added to minimize lithium phosphate formation and promote the formation of lithium carbonate, which is significantly more water-soluble than lithium phosphate.

Figure 11 shows that the addition of sodium carbonate to the mixed LFP-NMC black mass increased lithium recovery in water leaching. This effect was observed after the carbothermal process at temperatures of 450 °C and above. This suggests that carbonate compounds promote the formation of lithium carbonate and reduce the likelihood of lithium phosphate formation. The formation of lithium carbonate becomes more dominant at higher temperatures. In this study, lithium recovery improved from approximately 32% at 450 °C to around 60% at 850 °C with 100% selectivity following the carbothermal process. These findings highlight renewed opportunities for selective lithium recovery from mixed LFP-NMC black mass using water as a leaching agent.

The use of Na2CO3 additive in the carbothermal reduction of mixed black mass enhanced the formation of Li2CO3 over Li3PO4. As indicated by Raman spectra shown in Fig. 10, carbothermal treatment without Na2CO3 addition produced lithium compound primarily in the form of Li3PO4, with no evidence of Li2CO3. However, when Na2CO3 was added to, Raman spectra in Fig. 12 showed lithium in the form of Li2CO3. In Fig. 12, the spectrum at Spot 1 shows characteristics of Na2CO3, indicating an incomplete reaction within the black mass. Additionally, Na2CO3 did not decompose into Na2O and CO2 at the experimental temperatures, enabling solid-state reactions among the components. This is demonstrated by the presence of a new solid phase of Na3PO4, observed in the Raman spectrum at Spot 2. The formation of Na3PO4 is advantageous since it can liberate lithium to instead bond with carbonate and form Li2CO3. This is evident in the spectrum at Spot 3, which shows Li2CO3 along with the presence of Na-O bonds from Na2CO3. Thus, the carbothermal reduction for the mixed black mass can lead to significant improvement of lithium recovery in water leaching, as illustrated in Fig. 11.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates the potential of the carbothermal reduction method combined with atmospheric water leaching for efficient lithium recovery from mixed NMC-LFP battery black mass. For pure NMC black mass, optimized carbothermal conditions (950 °C, 15 °C/min heating rate, 2 h) achieved an impressive lithium recovery of 95.7 ± 0.31% with 100% selectivity, facilitated by the formation of water-soluble compounds such as Li2CO3 and Li2O. However, the introduction of LFP black mass significantly disrupted the process, reducing lithium recovery to 9.78 ± 0.44% (LFP: NMC 50%:50%) due to the formation of highly water-insoluble Li3PO4 and the entrapment of lithium within Fe-Ni-Co and Ni-Co alloy matrices. To address these challenges, the addition of carbonate compounds, namely in this study in the form of Na2CO3, during the carbothermal reduction of mixed black mass was investigated as a strategy to suppress Li3PO4 formation. This approach enhanced lithium recovery to 59.47% with 100% selectivity by stabilizing lithium as Li2CO3, a water-soluble compound. The results highlight the effectiveness of Na2CO3 as a promising additive for improving lithium recovery from mixed battery chemistries. These findings not only establish a practical pathway for recycling mixed NMC-LFP battery black mass but also contribute to the development of sustainable and environmentally friendly recycling technologies. The use of carbothermal reduction and selective water leaching under atmospheric conditions represents a scalable and low-impact approach for battery recycling, addressing critical challenges in the circular economy for lithium-ion batteries. Future work should focus on further optimizing additive usage, process scaling, and environmental impact analysis to realize full-scale implementation.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Alcaraz, L., Rodríguez-Largo, O., Barquero-Carmona, G. & López, F. A. Recovery of lithium from spent NMC batteries through water leaching, carbothermic reduction, and evaporative crystallization process. J. Power Sources. 619, 235215 (2024).

Mohanty, N., Goyal, N. K. & Naikan, V. N. A. A comparative analysis of operational planning for battery swapping and fast charging in electric vehicles. Life Cycle Reliab. Saf. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41872-024-00288-0 (2024).

Stan, A. I., Swierczynski, M., Stroe, D. I., Teodorescu, R. & Andreasen, S. J. Lithium ion battery chemistries from renewable energy storage to automotive and back-up power applications—An overview. In International Conference on Optimization of Electrical and Electronic Equipment (OPTIM) 713–720 (IEEE, 2014). https://doi.org/10.1109/OPTIM.2014.6850936

Ranjbar, A. H., Banaei, A., Khoobroo, A. & Fahimi, B. Online estimation of state of charge in Li-ion batteries using impulse response concept. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid. 3, 360–367 (2012).

Nekahi, A. et al. Comparative issues of metal-ion batteries toward sustainable energy storage: Lithium vs. sodium. Batteries. 10, 279 (2024).

Miao, Y., Hynan, P., von Jouanne, A. & Yokochi, A. Current li-ion battery technologies in electric vehicles and opportunities for advancements. Energies (Basel). 12, 1074 (2019).

Yang, G. et al. Exploration of physical recovery techniques and economic viability for retired lithium nickel cobalt manganese oxide-type lithium-ion power batteries. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 26, 3571–3583 (2024).

Yu, W. et al. Controlled carbothermic reduction for enhanced recovery of metals from spent lithium-ion batteries. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 194, 107005 (2023).

Ning, Y. et al. Reducing the environmental impact of lithium-ion battery recycling through co-processing of NCM and LFP. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 187, 810–819 (2024).

Zou, Y., Chernyaev, A., Ossama, M., Seisko, S. & Lundström, M. Leaching of NMC industrial black mass in the presence of LFP. Sci. Rep. 14, 10818 (2024).

Pavón, S., Kaiser, D., Mende, R. & Bertau, M. The COOL-process—A selective approach for recycling lithium batteries. Metals (Basel). 11, 259 (2021).

Sarkar, M., Hossain, R. & Sahajwalla, V. Sustainable recovery and resynthesis of electroactive materials from spent Li-ion batteries to ensure material sustainability. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 200, 107292 (2024).

Yan, Z., Sattar, A. & Li, Z. Priority lithium recovery from spent Li-ion batteries via carbothermal reduction with water leaching. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 192, 106937 (2023).

Huang, Z. et al. Metal reclamation from spent Lithium-ion battery cathode materials: Directional conversion of metals based on hydrogen reduction. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 10, 756–765 (2022).

Lombardo, G., Ebin, B., Foreman, S. J., Steenari, M. R., Petranikova, M. & B.-M. & Chemical transformations in Li-Ion battery electrode materials by carbothermic reduction. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 7, 13668–13679 (2019).

Wang, W., Han, Y., Zhang, T., Zhang, L. & Xu, S. Alkali metal salt catalyzed carbothermic reduction for sustainable recovery of LiCoO 2: Accurately controlled reduction and efficient water leaching. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 7, 16729–16737 (2019).

Seidell, A. Solubilities of Inorganic and Organic Compounds (D. Van Nostrand Company, 1919).

Jolodosky, A. et al. Neutronics and activation analysis of lithium-based ternary alloys in IFE blankets. Fusion Eng. Des. 107, 1–12 (2016).

Amarasekara, A. S. & Shrestha, A. B. Facile recovery of lithium as Li2CO3 or Li2O from α-hydroxy-carboxylic acid chelates through pyrolysis and the decomposition mechanism. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol. 179, 106471 (2024).

Kishimoto, H., Yamaji, K., Brito, M. E., Horita, T. & Yokokawa, H. Generalized Ellingham diagrams for utilization in solid oxide fuel cells. J. Min. Metall. Sect. B. 44, 39–48 (2008).

Devi, T. G. & Kannan, M. P. X-ray diffraction (XRD) studies on the Chemical States of some metal species in cellulosic chars and the Ellingham diagrams. Energy Fuels. 21, 596–601 (2007).

Qiao, R. et al. Transition-metal redox evolution in LiNi0.5Mn0.3Co0.2O2 electrodes at high potentials. J. Power Sources. 360, 294–300 (2017).

Jia, K. et al. Degradation mechanisms of electrodes promotes direct regeneration of spent Li-Ion batteries: A review. Adv. Mater. 36, 2313273 (2024).

de Jesus Silva, A. J., Contreras, M. M. & Nascimento, C. R. & Da Costa, M. F. Kinetics of thermal degradation and lifetime study of poly(vinylidene fluoride) (PVDF) subjected to bioethanol fuel accelerated aging. Heliyon 6, e04573 (2020).

Nishiyama, T. et al. Crystalline structure control of poly(vinylidene fluoride) films with the antisolvent addition method. Polym. J. 48, 1035–1038 (2016).

Wu, L. et al. Recent advances in the preparation of PVDF-based piezoelectric materials. Nanotechnol Rev. 11, 1386–1407 (2022).

Zhang, D. E., Ni, X. M., Zhang, X. J. & Zheng, H. G. Synthesis and characterization of Ni–Co needle-like alloys in water-in-oil microemulsion. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 302, 290–293 (2006).

Shinoda, K., Yamamoto, T. & Suzuki, S. Characterization of selective oxidation of manganese in surface layers of Fe–Mn alloys by different analytical methods. ISIJ Int. 53, 2000–2006 (2013).

Aprilianto, D. R., Perdana, I., Petrus, H. T. B. M. & Rochmadi & Effect of sulfate and carbonate ions on lithium carbonate precipitation from a low concentration lithium containing solution. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 63, 4918–4933 (2024).

Jones, W. B., Darvin, J. R., O’Rourke, P. E. & Fessler, K. A. S. Isotopic signatures of lithium carbonate and lithium hydroxide monohydrate measured using Raman spectroscopy. Appl. Spectrosc. 77, 151–159 (2023).

Zhang, L. et al. First spectroscopic identification of pyrocarbonate for high CO2 flux membranes containing highly interconnected three dimensional ionic channels. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 15, 13147 (2013).

Tang, C., Liao, Z., Zhong, Q. & Zhou, Z. Raman Spectra and microstructure characteristics of dendrite in Xingjiang nephrite gravel. Guang Pu Xue Yu Guang Pu Fen Xi. 37, 456–460 (2017).

Ayu, N. I. P., Kartini, E., Prayogi, L. D., Faisal, M. & Supardi Crystal structure analysis of Li3PO4 powder prepared by wet chemical reaction and solid-state reaction by using X-ray diffraction (XRD). Ionics (Kiel). 22, 1051–1057 (2016).

Song, Y. J. Recovery of lithium as Li3PO4 from waste water in a LIB recycling process. Korean J. Met. Mater. 56, 755–762 (2018).

Anderson, A. J., Clark, A. H., Gray, S., The occurrence and & origin of zabuyelite (Li2CO3) in spodumene-hosted fluid inclusions: Implications for the internal evolution of rare-element granitic pegmatites. Can. Mineral. 39, 1513–1527 (2001).

Hu, Q. et al. Anharmonic lattice dynamics dominated ion diffusion in γ-Li3PO4. J. Solid State Chem. 333, 124636 (2024).

Sabat, K. C. Iron production by hydrogen plasma. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 1172, 012043 (2019).

Oshtrakh, M. I. et al. Study of metallic Fe-Ni-Co alloy and stony part isolated from Seymchan meteorite using X-ray diffraction, magnetization measurement and Mössbauer spectroscopy. J. Mol. Struct. 1174, 112–121 (2018).

Takeda, M., Onishi, T., Nakakubo, S. & Fujimoto, S. Physical properties of iron-oxide scales on Si-containing steels at high temperature. Mater. Trans. 50, 2242–2246 (2009).

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the financial support from the Research and Technology Innovation (RTI) PT. Pertamina (Persero) No. 4150282070.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

IP: Conceptualization, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing, Formal analysis, Supervision, Project administration, and Resources. DRA: Conceptualization, Validation, Methodology, Data Curation, Writing - Original Draft, and Visualization. FAF: Validation, Methodology, Data Curation, Writing - Original Draft, and Visualization. RF: Validation, Methodology, Data Curation, Writing - Original Draft, and Visualization. HTBMP: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing - Review & Editing, and Supervision. WA: Formal analysis, Writing - Review & Editing, and Supervision. MAM: Formal analysis, Writing - Review & Editing, and Supervision. HN: Writing - Review & Editing, Supervision, Project administration, and Funding acquisition. HSO: Writing - Review & Editing, Supervision, Project administration, and Funding acquisition. FF: Writing - Review & Editing, Supervision, Project administration, and Funding acquisition. ER: Writing - Review & Editing, Supervision, Project administration, and Funding acquisition. SUM: Writing - Review & Editing, Supervision, Project administration, and Funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Perdana, I., Aprilianto, D.R., Fadillah, F.A. et al. Lithium recovery from mixed spent LFP-NMC batteries through atmospheric water leaching. Sci Rep 15, 2591 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86542-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86542-6