Abstract

This study aimed at assessing the mechanical properties and degradation of commercial bioactive materials. The bioactive materials (Activa Bioactive Restorative, Beautifil Flow Plus F00, F03, Predicta Bulk Bioactive) and composite resin Filtek Supreme Flow were submitted to flexural and diametral tensile strength tests (FS, DTS), modulus of elasticity (ME) evaluation, and analysis of aging in 70% ethanol and saliva on their hardness and sorption. The results for DTS ranged from 33.16 MPa (Beautifil Flow Plus F03) to 47.74 MPa (Filtek Supreme Flow). The highest FS was 120.40 MPa (Predicta Bulk Bioactive), while the lowest values were 86.55 MPa (Activa Bioactive Restorative). Activa Bioactive Restorative showed the lowest ME, as well as the highest water sorption both in alcohol and artificial saliva. Moreover, aging in saliva induced a significant decrease in hardness for Activa Restorative (p < .01). Alcohol storage caused a significant decrease in hardness for all materials (p < .0001). All tested materials met the basic requirements for light-curing materials in terms of DTS and FS. However, all materials showed higher sorption in alcohol than in saliva, while hardness decreased significantly after 30 days. Predicta Bulk Bioactive presented the highest mechanical parameters, initial hardness, and the lowest sorption of alcohol and saliva.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Restorative dentistry represents one of the main dentistry disciplines in daily clinical practice. Resin composites are the restorative materials most frequently chosen nowadays in clinic; since they are also applied not only in restorative dentistry and prosthodontics but also in periodontology and dental surgery1.

Such resin-based materials are composed of organic matrices, inorganic fillers, coupling agents, and additives (photoinitiators, stabilizers and inhibitors)2. Bisphenol A-glycidyl methacrylate (BisGMA), urethane dimethacrylate (UDMA) or bisphenol A diglycidyl methacrylate ethoxylated (BisEMA) are considered the main cross-linking monomers in dental composites3. Because of their high viscosity, they are often combined with diluent monomers (i.e. triethylene glycol dimethacrylate; TEGDMA), which facilitate the incorporation of mineral fillers within the mixture and the handling of the formulations4. The fillers used in dental composites are mainly glass, quartz, and/or silica. The amount of fillers, and their particle size, shape, as well as their distribution also influence the physical and mechanical properties of composites5. A further important component in dental composites is the silane, which is a coupling agent that enhances the chemical bonding between the filler and the polymer matrix. Indeed, an effective bonding between organic matrix and inorganic fillers contrasts the aging processes and prevents cracks from occurring on the surface of the filler6.

It is important to highlight that incomplete polymerization of dental composites may result in the higher risk plaque accumulation; such bacteria may contribute to secondary caries formation7. To overcome such issues, several innovative dental materials have been doped with ion-releasing “bioactive” fillers (e.g. Bioactive glasses, Calcium silicates and calcium phosphates) that can protect the bonding interface and extend their longevity8,9. Moreover, several bioactive molecules such as bioactive glasses have been advocated to promote a specific biological response in organisms or cells by inducing chemical bonding or tissue formation (e.g. pulp tissue, dentin, and bone)10. Further bioactive polymeric compounds such as zinc oxide and polymer nanoparticles (e.g. 2-methacryloyloxyethyl phosphorylcholine - MPC) have been employed in the formulation of resin-based materials to confer some antimicrobial properties. On the other hand, bioreactive compounds able to release ions such as fluoride, calcium and phosphates may also exhibit an antibacterial effect11,12,13. Moreover, some bioactive materials can have an ion release and recharge that occurs due to pH changes in a wet environment14.

Several types of bioactive materials have been used in restorative dentistry, including pulp protection cements, placed directly or indirectly, based on calcium hydroxide or mineral aggregate (MTA). However, there is a further group of materials considered as “bioactive” to fill tooth cavities or treat dental caries of constituting glass ionomer cements (GICs), resin-modified glass ionomers cements (RMGICs), GICs associated with calcium aluminate and ion-releasing composites10,15.

Activa Bioactive Restorative (Pulpdent Corporation, Watertown, MA, USA) is a RMGIC. The material is a combination of an ionic resin matrix, a shock-absorbing resin component, and “bioactive” resin-modified calcium phosphate filler (MCP) that may mimic the chemical and physical properties of natural teeth16. The manufacturer claims that such a material is characterized by a low polymerization volumetric shrinkage (1.7%) and can be placed in layers of 4–5 mm, which is associated with a shorter reconstruction time and lower technique sensitivity17,18.

Beautifil Flow Plus (Shofu, Kyoto, Japan) is a light-cured hybrid liquid composite, available in two flow levels, F00 (stable) and F03 (flowable)19. These materials are also described as giomers, combining fluoride release, GICs loading, and the aesthetics, physical properties, and performance properties of composite resins20. The manufacturer claims that the S-PRG filler releases several ions that can induce remineralization of the dentin matrix and improve the acid resistance of the enamel20,21.

Predicta Bulk Bioactive (Parkell, New York, USA) is a dual-cure composite that can be used for the restoration of any size of cavity without the need of any additional layer22. This material offers the release and recharge of ions such as Ca2+, PO43−, and fluoride23. Additionally, it also contains a novel monomer (Poly-2-HEMA), which has been advocated to reduce the risk of potentially toxic effects of BisGMA-based compounds12.

Nevertheless, the most relevant issue concerning tooth-filling restorative materials is still related to longevity and stability during a long clinical service. In addition to mechanical factors, materials are exposed to extreme temperatures and pH related to ingested food and acid produced by microbial flora. Low pH may result in deterioration of mechanical properties because acids promote the decomposition of matrix components resin monomer and filler. Indeed, unpolymerized methacrylate monomers may leach out so enhancing water penetration, and plasticization of the polymer matrix24. It is well documented that the lower the pH of the environment, the faster the degradation of composite materials24. Furthermore, drastic changes in temperature can influence the chemical reactions between components, so causing material instability due to oxidation and chemical degradation of the polymer matrix25.

Despite the significant development of new restorative dental materials over the last two decades, further research is still needed to assess their real durability, wear behaviour in the oral environment, bioactive potential, and mechanical, biological and optical properties. Thus, this study aimed at evaluating the mechanical properties of some commercial restorative ion-releasing “bioactive” materials and compare them to a conventional resin composite. The null hypothesis was that there would be no difference in flexural and diametral tensile strength, modulus of elasticity, hardness, and sorption between the tested “bioactive” restorative materials and the conventional resin composite.

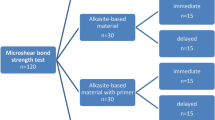

Materials and methods

In the present study, four ion-releasing “bioactive” restorative materials and one conventional resin composite (control), were analysed. The details and further characteristics of tested materials are depicted in Table 1. The sample size was determined by assessing previous similar research and it was calculated with the following parameters: effect size of 10%, standard deviation of 7%, significance level of 0.05, and power of 80%. The minimum sample size of 9 was determined (G*Power software ver. 3.1.9.7 for Windows; Heinrich-Heine-Universität Düsseldorf, Düsseldorf, Germany; http://www.gpower.hhu.de/)26.

Flexural strength (FS) and modulus of elasticity (ME)

The three-point bending tests were carried out using Zwick/Roell Z020 machine (Zwick/Roell, Germany) at a traverse speed of 1 mm/min, load cell 5 kN and support spacing 20 mm (support and pin radius r = 1 mm) according to PN-EN ISO 4049:2019 27. Ten specimens (25 mm long, 2 mm wide and 2 mm thick) per group were evaluated. Polymerization of the composites was carried out using the Curing Pen (EIGHTEETH Changzhou City, Jiangsu Province, China) with a power of 1250 mW/cm2, according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. The exposure was started in the centre of the specimens and moved towards both edges of every half of the light curing tip diameter (PN-EN ISO 4049:2019 standard)27. After preparation, the specimens were dry at room temperature, and the tests were performed after 24 h after their preparation. The modulus of elasticity and maximum failure load (Newton, N) of each specimen were recorded.

The flexural strength (FS) values (σf, MPa) were calculated using Formula (1):

where:

\(\:{\upsigma\:}\text{f}\)– three-point bending flexural strength [MPa]

F – force, which destroyed the specimen (N);

l- distance between supports, 20 mm;

b- width of the specimen (mm);

h- height of the specimen (mm).

The ME [E, GPa] was determined using the following Formula (2):

where:

d – specimen’s deflection corresponding to F [mm].

The diametral tensile strength (DTS)

The DTS was performed with the use of a Zwick/Roell Z020 universal testing machine (Zwick/Roell, Germany) at a traverse speed of 1 mm/min. Ten cylindrical specimens (ø = 6 mm x 3 mm) per group were used. Polymerization of the composites was carried out using the Curing Pen (EIGHTEETH Changzhou City, Jiangsu Province, China) with a power of 1250 mW/cm2, according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. After preparation, the specimens were stored in the dark at room temperature and assessed 24 h after their preparation.

The DTS values were calculated using Formula (3):

where:

F – force, which destroyed the specimen (N);

d – diameter of the specimen (mm);

h – height of the specimen (mm).

Sorption

The sorption properties of the tested materials were investigated according to ISO 4049:2019 27. Twenty disc-shaped specimens (ø = 15 mm x 1 mm) using a silicone mould were prepared. The specimens were left undisturbed at room temperature for 30 min and subsequently, their initial weight (m1) was determined using a Radwag XA 82/220/X scale (RADWAG, Radom, Poland) (d = 0.01/0.1 mg). All the specimens were then randomly divided into 2 subgroups: Group Alcohol - they were immersed (n = 10) in 70% ethanol (Warchem, Warsaw, Poland) and Group Saliva (n = 10), where they were stored in saliva PSB-2 A (Capricorn Scientific GmbH, Ebsdorfergrund, Germany). The specimens were placed in an incubator CLW 115 STD (POL-EKO APARATURA, Wodzislaw Slaski, Poland) at 37 °C for up to 30 days. The storage solutions were changed every 24 h. At the end of each storage period (after 1, 3, 7, 14, 21, and 30 days), the discs were dried with absorbent paper and immediately weighted (m2). Finally, the specimens were placed into a desiccator at 37 °C and measured until a constant weight was achieved (m3).

The sorption (S) was calculated according to Formula (4):

S=\(\:\frac{{m}_{2}-{m}_{3}}{V}[{\upmu\:}\text{g}/{mm}^{3}]\) (4)

where:

m2 – weight of the specimen after immersion for a specified period (µg).

m3 – weight of the reconditioned specimen (µg).

V – volume of the specimens (mm3).

Hardness

The hardness of the tested materials was measured through the Vickers method (Hardness Vickers, HV). The analysis was performed using a semi-automatic Zwick/Roell ZHµ hardness tester (Zwick/Roell, Germany). The tests were carried out for a load of 1 kg for 15 s, which corresponds to the standardized HV1 test28.

Twenty disc-shaped specimens (ø = 10 mm x 2 mm) were prepared from each material and polymerized following the manufacturer’s recommendations. After 30 min the initial hardness was measured, and then all the specimens were randomly divided into two groups as described above (n = 10). Group Alcohol – Immersion in a 70% ethanol solution (Warchem, ); group Saliva - immersion in PSB-2 A saliva (Capricorn Scientific). Solutions were replaced every 24 h throughout the 30-day study period. The hardness analysis was analysed at 1, 3, 7, 14, 21, 28, and 30 days of aging.

Statistical analysis

The normality of the data distribution was tested with Shapiro-Wilk test, and the Brown–Forsythe and Levene tests were used to assess the equality of variances. In case of ME and DTS, the comparison between groups was conducted with Kruskal-Wallis test, while in the case of TPB with use of Welch’s t-test and Tukey (RIR) post-hoc test. The changes of weight and hardness over time in different storage media were assessed with the single factor repeated measures ANOVA and Scheffé post-hoc test. All statistical analyses were conducted with the statistical software package Statistica v. 13.3 (StatSoft, Inc., OK, USA), and statistical significance was set up at p ≤ .05.

RESULTS

Flexural strength and modulus of elasticity (ME)

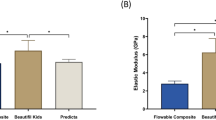

The highest median value of FS was 120.40 MPa (Predicta Bulk Bioactive), while the lowest one was 86.55 MPa (Activa Bioactive Restorative) (Fig. 1). Predicta Bulk Bioactive exhibited a FS significantly higher than Activa Bioactive Restorative (p ≤ .001), Beautifil Flow Plus F00 (p ≤ .01) and Beautifil Flow Plus F03 (p ≤ .001). Additionally, Filtek Supreme Flow was found to exhibit a FS significantly higher than that of Activa Bioactive Restorative (p ≤ .001), Beautifil Flow Plus F00 (p ≤ .01) and Beautifil Flow Plus F03 (p ≤ .001).

The highest modulus of elasticity was obtained in the specimens of Predicta Bulk Bioactive (7.27 GPa), while the lowest ME was detected for Activa Bioactive Restorative (3.45 GPa) (Table 2). Activa Bioactive Restorative showed a modulus statistically significantly lower compared to those obtained with the other tested materials (p ≤ .05), except for Filtek Supreme Flow.

Diametral tensile strength (DTS)

The lowest median DTS values was 33.16 MPa (Beautifil Flow Plus F03), while the highest one was 47.74 MPa (Filtek Supreme Flow) (Fig. 2). Predicta Bulk Bioactvie had a DTS significantly higher compared to Beautifil Flow Plus F03 (p ≤ .001) and Beautifil Flow Plus F00 (p ≤ .05). Moreover, Filtek Supreme Flow exhibited a DTS significantly higher compared to Beautifil Flow Plus F03 (p ≤ .001).

Sorption

The changes over time of sorption in different storage media are presented in Fig. 3. When analysing such results for all the tested materials, the highest sorption was observed during the first 7–14 days of storage in all specimens/groups.

After 30-day incubation, Activa Bioactive Restorative exhibited the highest sorption in both media (106.49 µg/mm3 in alcohol and 46.27 µg/mm3 in saliva) (Table 3; Fig. 4).

After 30 days, in both storage media (alcohol and saliva), a significantly higher sorption was observed for Activa Bioactive Restorative compared to Filtek Supreme Flow (p ≤ .05) and Predicta Bulk Bioactive (p ≤ .05). Additionally, Activa Bioactive Restorative exhibited higher sorption when stored in alcohol rather than saliva (p < .05).

Hardness

The changes in hardness (HV) at the baseline (30 min.) and after aging (30 days) in different storage media (alcohol and saliva) are presented in Table 4.

After 30-day incubation in alcohol, a significant decrease in hardness was observed for all tested materials (p < .0001). After 30-day immersion in saliva, a significant drop in hardness was observed for Activa Bioactive Restorative (p < .01), while Filtek Supreme Flow (p < .0001) showed an increase in hardness. The hardness of the specimens in all tested groups after 30-day storage in alcohol decreased significantly when compared to saliva (p < .001). The changes over time in hardness in different media can be seen in Fig. 5.

Discussion

In this study, the DTS, FS and modulus of elasticity of several modern “bioactive” materials and a conventional resin composite were assessed, as well as the influence of aging in ethanol (70 vol%) and PSB-2 A saliva on their hardness and sorption. The results obtained in this study induced us to reject the null hypothesis since important differences were found in the parameters mentioned above between tested restorative materials.

Laboratory tests are crucial for several reasons, including ensuring safety, reliability, and quality in various applications in a standardized environment. For instance, the evaluation of DTS is critical because tensile stresses often occur during occlusal loads29,30. A material with low DTS would fail under chewing forces, which might result in the bond destruction between the composite and the tooth and, consequently, hypersensitivity, caries, or eventually the failure of the restoration. According to the American Dental Association (ADA), resin materials should exhibit a minimum DTS value of 24 MPa31, while the reported range for composite materials varied from 30 to 55 MPa32,33. In the present study, the DTS of all tested materials met the minimum required criteria and ranged between 33.16 MPa (Beautifil Flow Plus F03) and 47.74 MPa (Filtek Supreme Flow). It has been reported that Activa Bioactive Restorative exhibited a DTS of 33.90 MPa34 and 39.2 MPa30, which was confirmed in the present study (39.22 MPa). According to the manufacturer, the DTS of Predicta Bulk Bioactive can reach ca. 53 MPa35 which was slightly higher than that obtained in the present study for the same material (47.74 MPa). In literature, there is a lack of information on the DTS of modern “bioactive” restorative materials such as Beautifil Flow Plus F00 and F03, hence direct comparison has not been possible so far.

It should be revealed that this test might give different values for apparently similar materials due to differences in the polymeric matrix, filler size, and bond between fillers and matrix29,36. Monomers with a relatively low molecular weight (UDMA, TEGDMA, BisEMA) were claimed to reduce viscosity, facilitate the incorporation of fillers, and increase the degree of conversion, as well as some mechanical parameters33,37. In the present study, Filtek Supreme Flow, which contained those monomers mentioned above exhibited the highest DTS (47.74 MPa). Comparable results were found for Predicta Bulk Bioactive (47.08 MPa). These materials comprised nanofillers, which might justify such similar results. Ion-releasing “bioactive” restorative materials could contain relatively low volumes of nanoparticles (having large surface area), that were capable of releasing large quantities of ions. Additionally, these materials comprised reinforcing fillers that may improve their strength5. Conversely, the lowest values of DTS were found for Beautifil Flow Plus F00 (36.62 MPa) and Beautifil Flow Plus F03 (33.16 MPa). Both materials contained pre-reacted surface-reacted S-PRG glass ionomer fillers that continuously released ions. It could result in micro-crack formation and separation of matrix and filler, and in deterioration of mechanical properties38,39.

Flexural strength (FS), in turn, is the maximum stress recorded during the bending of the specimens at the moment of their failure. This parameter is clinically important in class I, II, III, and IV restorations40 in which the material must withstand high masticatory forces of 463–654 N in healthy individuals or 186–416 N in patients with temporomandibular disorders and bruxism41. The higher the FS value, the lower the tendency to (bulk, margin) crack due to functional forces29,30. FS of dental restorative materials should be greater than 50 MPa27, while those materials that are supposed to restore occlusal surfaces should have a FS higher than 80 MPa according to ISO 4049 27. In the present study, all materials achieved an FS greater than the latter. The highest median value was 120.40 MPa for Predicta Bulk Bioactive, which was quite similar to the data provided by the manufacturer (130 MPa)35. In accordance with previous studies42, the lower FS value (77.97 MPa) was obtained with Predicta Bulk Restorative. In the current study, the lowest FS was observed in the specimens created using Activa Bioactive Restorative (86.55 MPa). Indeed, previous studies revealed higher FS for Activa Bioactive Restorative, which reported values up to 100 MPa43 and 111.82 MPa39. On the contrary, one study reported lower FS for Activa Bioactive Restorative (70 MPa)43. Such discrepancies might be a result of the storage conditions of the specimens before testing (dry or wet); higher FS values were observed for materials stored dry before testing43.

It is worth emphasizing that FS values depended mainly on the composition of the organic matrix and filler characteristics (type, content, morphology). The filler content was claimed to exert a major influence on this parameter; the higher the amount of filler, the higher FS29,44,45. This hypothesis was partially confirmed by the present results, where Activa Bioactive Restorative exhibited the lowest FS (86.55 MPa) and contained the lowest amount of filler (56%wg). On the contrary, Beautifil Flow Plus F00 and F03 despite the highest filler content (67.3% and 66.8% respectively), showed lower FS values, which indicated that besides the filler content, also the filler type may affect such a mechanical property. Furthermore, we hypothesize that these materials comprised either partially (i.e. superficially) reacted or unreacted calcium glass fillers releasing ions. These fillers were more reactive and intensively interacted with phosphates in the oral environment, so diminishing some specific mechanical properties and strength46,47.

The elastic modulus is also an important feature for materials applied in the occlusal area48. The higher the elastic modulus value, the greater the stiffness and therefore the stress required to induce the deformation of the material16. In the current study, the lowest elastic modulus was recorded for Activa Bioactive Restorative (3.45 GPa). Some previous studies reported that the modulus of such materials can range between 1.43 GPa49 to 4.45 GPa50. Our study showed that the highest value was that of Predicta Bulk Restorative (7.27 GPa), while others previous researchers obtained a modulus of 4.32 GPa42. Beautifil Flow demonstrated a modulus of 6.72 GPa for F00 and 7.06 GPa for F03. Hence, higher values of the elastic modulus are provided by the manufacturer (8.5 GPa: F00; 8.4 GPa: F03), and others showed 8.27 GPa for F03 51. In the present study, the modulus of elasticity for Filtek Supreme Flow was 6.51 GPa, which was similar to the value provided by the manufacturer (7.1 GPa)52. Some studies established that there may be a correlation between elastic modulus and filler volume; the higher the filler content53,54, the greater the flexural modulus, which was confirmed by the present study. It is worth mentioning that the modulus of elasticity, except for Activa Bioactive Restorative, was close to that of the sound human dentin (8.7–30 GPa)55, but significantly lower than for enamel (50–120 GPa)54,55.

Vickers test provides accuracy, versatility, and reliability in the assessment of the hardness of the surfaces of materials and dental tissues. It is important to state that surface’s hardness of restorative materials is affected by various factors such as kind of the matrix, the amount and size of filler particles, and the type of filler distribution55. It reflects the material’s resistance to indentation; it gives important indications about the material’s wear and scratching resistance. Therefore, the material with reduced hardness would be more susceptible to surface and interface damage, which might result in a reduction in restoration volume, gap formation, and eventually in restoration failure29. The overall hardness of composite materials depending on the inorganic filling particle size and surface of measurement (top/bottom) were as follows: microfill: 19–38 HV, hybrid: 36–105 HV, nanofill: 44–111 HV56. Moreover, the hardness of high and low-viscosity bulk-fill composites materials ranged between 32.8 and 101.5 HV57. It is worth mentioning that the obtained hardness should preferably reach a value comparable to that of dentin (53 to 66 HV) or eventually to that of enamel (250 to 360 HV)58.

In the present study, Activa Bioactive Restorative was characterized by the relatively low initial hardness (HV: 27.36), which are in accordance with those of previous studies59. A further study claimed the hardness of Activa being 38 HV, which was lower than other fluoride-releasing materials [Dyract (71 HV), CompGlass (48 HV), BEAUTIFIL-II (54 HV), GC Fuji II LC (68 HV)]43. Therefore, it is clear that the hardness of Activa Bioactive Restorative might limit its clinical application as lining material or as class V and deciduous teeth restorative material17. Hence, when placed in the area of occlusal loads, it should be covered with a material exhibiting higher mechanical properties17. Previous study showed that the hardness of Beautifil Flow Plus was 41.56 HV59, which is similar to the values obtained in the current study (initial hardness ~ 44 HV). According to the manufacturer, the hardness of Filtek Supreme Flow Restorative is approx. 57 HV, being higher than the values obtained in our research (~ 43 HV).

Changes in the mechanical properties of composite materials caused by storage in various aging media are the result of chemical and physical degradation, which are also known as diffusion-related solvent sorption60. These processes induce softening of the resin matrix and reduce polymeric chain interactions. Additionally, hydrolysis causes the breakdown of Si-O-Si bonds between the filler particles and the silane, which consequently weakens the overall structure of the material61. The storage conditions also affect the degree of conversion and water sorption, so decreasing flexural properties, as well as other mechanical properties47. Moreover, it was reported that the organic matrix was mainly responsible for the aging effects (hydrophilic properties of dental resins, such as Bis-GMA and HEMA), while the degradation of the filler fraction played a minor role60. Therefore, materials with a higher filler content would be more resistant to degradation processes, as confirmed in the current study. Activa Bioactive Restorative is the tested material with the smallest amount of filler (56%), so when compared to the other tested materials (filler amount: 65-67.3%) it revealed the highest changes in hardness in both storage media. Previous studies reported an evident reduction in hardness of composite materials after aging39,60,62. In the present study, the hardness of all tested materials decreased after storage, except for Filtek Supreme Flow when stored in saliva. It can be hypothesized that the increase in hardness of this material might be related to the nanosize of filler. Indeed, some researchers suggested that when smaller filler particles were employed, water diffusion into deeper layers occurred more slowly63,64. This situation prevents the plasticization of the resin matric in composite materials. In addition, another material also containing nanofiller (Predicta Bulk Bioactive) exhibited slightly reduced hardness after aging in saliva.

It is also important to highlight a significant greater decrease in hardness when the specimens of all the tested materials were stored in alcohol than saliva. The ethanol decreased the mechanical parameters of composites65,66,67,68 due to the higher solubility of the organic matrix in this solvent. This is mainly due to the fact that both substances exhibited similar Hoy’s solubility [ethanol 26.1 (J/cm3)½; methacrylates resins 19.2–23.6 (J/cm3)½]69,70. As a result, the penetration of ethanol as a more organophilic molecule unlike other water-based aging liquids occurred much more easily60.

The water sorption of tested material, according to ISO-4049-2019 standards, should be equal to or less than 40 µg/mm3 27. This parameter might be influenced by the type of medium and storage time, as well as the content and composition of the polymer matrix.

The highest average water sorption was found in Activa Bioactive Restorative (46.27 µg/mm3 in saliva), which exceeded the ISO standard values. Slightly lower values (44.2 µg/mm3) after 4-month storage period in distilled water were reported by Alzahrani et al.71. The increased sorption might be explained by the hydrophilic components of the matrix, such as polyacrylic acid and phosphate groups that were boosting water sorption71. Moreover, the structure of the matrix with the modified calcium phosphate filler would have allowed the water to easily diffuse and reach the particles and induce releasing of ions72. Composites with 40% bioactive glass fillers were proved to exhibit important water sorption, something like six times higher than materials without this type of filler73. Moreover, it is important to state that Activa Bioactive Restorative, contains 21.8 wt% of reactive glass ionomer fillers74. On the other hand, Beautifil Flow Plus materials, which contains alumino-fluoro-borosilicate glass of 50–60 wt% 75 also showed high sorption. Moreover, the composition of the polymer matrix could result in increased (water and alcohol) sorption; indeed TEGDMA was demonstrated to have the highest water sorption, followed by Bis-GMA, UDMA, and Bis-EMA76,77. Between all the tested materials containing TEGDMA (Beautifil Flow Plus F00, F03, and Filtek Supreme Flow), Filtek Supreme Flow showed the lowest sorption in both storage media [24.90 µg/mm3 in alcohol and 24.48 µg/mm3 in saliva; Beautifil Flow Plus F00 (39.83 µg/mm3 in alcohol and 38.52 µg/mm3 in saliva) and Beautifil Flow Plus F03 (37.15 µg/mm3 in alcohol and 33.88 µg/mm3 in saliva)]. According to the manufacturer, the amount of TEGDMA in Filtek Supreme Flow was reduced (< 10%), thus the sorption was limited52. Beautifil Flow Plus contained a higher volume of TEGDMA, namely 10–20% 75. In addition, Beautifil Flow Plus comprised 15–25% of Bis-GMA while Filtek Supreme Flow only 5–10%. Interestingly, Activa Bioactive Restorative exhibited statistically higher sorption when it was stored in alcohol (106.49 µg/mm3) than in saliva (p < .05). Unfortunately, there were no studies on alcohol sorption of tested bioactive materials. However, available results on flow and bulk-fill materials indicated that a storage medium containing alcohol increased the water sorption78,79. The other tested materials met the sorption criterion (40 µg/mm3) in both incubation fluids.

When analyzing in our study the changes in sorption over time, the highest sorption was noted during the first 7–14 days of observation, regardless of the material and storage medium. Our results are in accordance with previous studies80,81, where maximum sorption was detected between the first 7 days after polymerization. This might be due to the continuous setting reaction that occurred after the initial light exposure82. In the present study, stabilization in water sorption was observed for aqueous solutions after approximately 2 weeks. Conversely, for alcohol storage such stabilization occurred after 3–4 weeks (21–28 days). The observed changes in sorption over time in water were confirmed by previous studies that proved an increase at 1, 7 and 14 days followed by gradual sorption over a long period until a balanced state was obtained after 14 days82,83.

Conclusions

Within the limitations of the present study, the following conclusions can be drawn:

-

1.

All tested materials met the requirements for light-curing resin-based materials in terms of DTS and FS.

-

2.

Predicta Bulk Bioactive and Filtek Supreme Flow showed significantly higher FS and DTS than all the other materials tested in this study. .

-

3.

Activa Bioactive Restorative demonstrated an importantly lower modulus of elasticity than other tested materials, except for Filtek Supreme Flow.

-

4.

Predicta Bulk Bioactive and Filtek Supreme Flow exhibited significantly lower saliva and alcohol sorption compared to the other tested materials. However, all the tested materials showed higher sorption of alcohol than saliva.

-

5.

The hardness of all the tested materials decreased significantly after 30-day alcohol storage.

-

6.

After storage in saliva, the hardness of Activa Bioactive Restorative decreased, while that if the Filtek Supreme Flow increased. However, alcohol storage induces overall a significant decrease in hardness compared to saliva.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Szalewski, L., Wójcik, D., Bogucki, M. & Szkutnik, J. & Różyło-Kalinowska, I. The influence of popular beverages on mechanical properties of composite resins. Materials vol. 14 at (2021). https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14113097

Zhou, X. et al. Development and status of resin composite as dental restorative materials. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 136, 1–12 (2019).

Ferracane, J. L. Resin-based composite performance: are there some things we can’t predict? Dent. Mater. 29, 51–58 (2013).

Cho, K., Rajan, G., Farrar, P., Prentice, L. & Prusty, B. G. Dental resin composites: a review on materials to product realizations. Compos. Part. B Eng. 230, 109495 (2022).

Liu, J. et al. The development of filler morphology in dental resin composites: a review. Mater. (Basel Switzerland) 14, (2021).

Thadathil Varghese, J. et al. Influence of silane coupling agent on the mechanical performance of flowable fibre-reinforced dental composites. Dent. Mater. 38, 1173–1183 (2022).

Ferracane, J. L. Models of caries formation around dental composite restorations. J. Dent. Res. 96, 364–371 (2017).

Schwendicke, F., Al-Abdi, A., Pascual Moscardó, A., Ferrando Cascales, A. & Sauro, S. Remineralization effects of conventional and experimental ion-releasing materials in chemically or bacterially-induced dentin caries lesions. Dent. Mater. 35, 772–779 (2019).

Sauro, S. & Pashley, D. H. Strategies to stabilise dentine-bonded interfaces through remineralising operative approaches – state of the art. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 69, 39–57 (2016).

Özcan, M., da Garcia, L. & Volpato, C. A. F. R. M. Bioactive materials for direct and indirect restorations: concepts and applications. Front. Dent. Med. 2, (2021).

Ramburrun, P. et al. Recent advances in the development of Antimicrobial and Antifouling Biocompatible materials for Dental Applications. Mater. (Basel Switzerland) 14, (2021).

Kunert, M. et al. The Cytotoxicity and genotoxicity of bioactive dental materials. Cells 11, (2022).

Alambiaga-Caravaca, A. M. et al. Characterisation of experimental flowable composites containing fluoride-doped calcium phosphates as promising remineralising materials. J. Dent. 143, 104906 (2024).

Sabae, H. O., Nabih, S. M. & Alsamolly, W. M. Fluoride release and anti-bacterial activity of different bioactive restorative materials: an in vitro comparative study. J. Stomatol. 76, 271–278 (2023).

Woźniak-Budych, M. J., Staszak, M. & Staszak, K. A critical review of dental biomaterials with an emphasis on biocompatibility. Dent. Med. Probl. 60, 709–739 (2023).

Carneiro, E. R. et al. Mechanical and Tribological Characterization of a Bioactive Composite Resin. Applied Sciences vol. 11 at (2021). https://doi.org/10.3390/app11178256

Lardani, L., Derchi, G., Marchio, V. & Carli, E. One-year clinical performance of Activa™ bioactive-restorative composite in primary molars. Child. (Basel Switzerland) 9, (2022).

Abdel-Maksoud, H. B., Bahanan, A. W., Alkhattabi, L. J. & Bakhsh, T. A. Evaluation of newly introduced Bioactive materials in terms of Cavity Floor Adaptation: OCT study. Mater. (Basel Switzerland) 14, (2021).

Rusnac, M. E., Gasparik, C., Delean, A. G., Aghiorghiesei, A. I. & Dudea, D. Optical properties and masking capacity of flowable giomers. Med. Pharm. Rep. 94, 99–105 (2021).

Abdel-karim, U. M., El-Eraky, M. & Etman, W. M. Three-year clinical evaluation of two nano-hybrid giomer restorative composites. Tanta Dent. J. 11, 213–222 (2014).

Takeuchi, H. et al. Surface pre-reacted glass-ionomer eluate protects gingival epithelium from penetration by lipopolysaccharides and peptidoglycans via transcription factor EB pathway. PLoS One. 17, e0271192 (2022).

Data Safety Sheet. Predicta TM Flow Dual Cure bulk-fill composite predicta TM Flow Dual Cure bulk-fill composite. 1–25 (2018).

Kunert, M. et al. Dentine remineralisation Induced by bioactive materials through mineral deposition: An in vitro study. Nanomaterials vol. 14 at (2024). https://doi.org/10.3390/nano14030274

Alhotan, A. et al. Influence of storing composite filling materials in a Low-pH artificial saliva on their mechanical properties—An in vitro study. Journal of Functional Biomaterials vol. 14 at (2023). https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb14060328

Szalewski, L., Szalewska, M., Jarosz, P., Woś, M. & Szymańska, J. Temperature changes in composite materials during photopolymerization. Applied Sciences vol. 11 at (2021). https://doi.org/10.3390/app11020474

Thanoon, H., Price, R. B. & Watts, D. C. Thermography and conversion of fast-cure composite photocured with quad-wave and laser curing lights compared to a conventional curing light. Dent. Mater. 40, 546–556 (2024).

STANDARD ISO 4049: Dentistry-Polymer-based restorative materials 2019. 1–28 (2019). (2019) 2019.

Frassetto, A. et al. Kinetics of polymerization and contraction stress development in self-adhesive resin cements. Dent. Mater. 28, 1032–1039 (2012).

Skapska, A., Komorek, Z., Cierech, M. & Mierzwinska-Nastalska, E. Comparison of mechanical properties of a self-adhesive composite cement and a heated composite material. Polymers vol. 14 at (2022). https://doi.org/10.3390/polym14132686

Domarecka, M. et al. A comparative study of the mechanical properties of selected dental composites with a dual-curing system with light-curing composites. Coatings vol. 11 at (2021). https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings11101255

ANSI/ADA Specification No. 27: Resin-based filling material; American national standards institute (ANSI): Washington, DC, USA, (1993).

Razooki, A. & Aubi, I. Composite diametral tensile strength. World J. Dent. 9, 457–461 (2018).

Szczesio-Wlodarczyk, A., Domarecka, M., Kopacz, K., Sokolowski, J. & Bociong, K. An evaluation of the properties of urethane dimethacrylate-based dental resins. Mater. (Basel). 14, 1–16 (2021).

Beltagy, T. & Elhatery, A. Bioactive Resin modified GIC vs. Conventional one in Vivo and in Vitro Study. Egypt. Dent. J. 64, 1–15 (2018).

https://www.parkell.com/SSPApplications/NetSuite Inc, S. C. A. E. & Development /PDFs/IFUs/Predicta-Bulk-ifu-w.pdf

Sharafeddin, F., Motamedi, M. & Fattah, Z. Effect of preheating and precooling on the Flexural Strength and Modulus of elasticity of Nanohybrid and Silorane-based Composite. J. Dent. (Shiraz Iran). 16, 224–229 (2015).

Gonçalves, F., Kawano, Y., Pfeifer, C., Stansbury, J. & Braga, R. Influence of BisGMA, TEGDMA, and BisEMA contents on viscosity, conversion, and flexural strength of experimental resins and composites. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 117, 442–446 (2009).

Ilie, N. & Stawarczyk, B. Evaluation of modern bioactive restoratives for bulk-fill placement. J. Dent. 49, 46–53 (2016).

Kasraei, S., Haghi, S., Farzad, A., Malek, M. & Nejadkarimi, S. Comparative of flexural strength, hardness, and fluoride release of two bioactive restorative materials with RMGI and composite resin. Brazilian J. Oral Sci. 21, 1–16 (2022).

Alrahlah, A. Diametral tensile strength, flexural strength, and surface microhardness of bioactive bulk fill restorative. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 19, 13–19 (2018).

Tortopidis, D., Lyons, M. F. & Baxendale, R. H. Bite force, endurance and masseter muscle fatigue in healthy edentulous subjects and those with TMD. J. Oral Rehabil. 26, 321–328 (1999).

Ibrahim, M. S. et al. The demineralization resistance and mechanical assessments of different bioactive restorative materials for primary and permanent teeth: an in vitro study. BDJ Open. 10, 30 (2024).

Garoushi, S., Vallittu, P. K. & Lassila, L. Characterization of fluoride releasing restorative dental materials. Dent. Mater. J. 37, 293–300 (2018).

Giełzak, J., Szczesio-Wlodarczyk, A. & Bociong, K. Effect of Storage Temperature on Selected Strength Parameters of Dual-Cured Composite Cements. Journal of Functional Biomaterials vol. 14 at (2023). https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb14100487

Jun, S. K., Kim, D. A., Goo, H. J. & Lee, H. H. Investigation of the correlation between the different mechanical properties of resin composites. Dent. Mater. J. 32, 48–57 (2013).

Ito, S. et al. Effects of surface pre-reacted glass-ionomer fillers on mineral induction by phosphoprotein. J. Dent. 39, 72–79 (2011).

Yap, A. U., Choo, H. S., Choo, H. Y. & Yahya, N. A. Flexural properties of bioactive restoratives in cariogenic environments. Oper. Dent. 46, 448–456 (2021).

Scribante, A., Bollardi, M., Chiesa, M., Poggio, C. & Colombo, M. Flexural properties and elastic modulus of different esthetic restorative materials: Evaluation after exposure to acidic drink. Biomed Res. Int. 5109481 (2019). (2019).

Younis, S. & Alaa, E. Flexural Strength and Modulus of elasticity of two base materials. An in vitro comparative study. Egypt. Dent. J. 66, 1837–1843 (2020).

Bansal, R., Burgess, J. & Lawson, N. C. Wear of an enhanced resin-modified glass-ionomer restorative material. Am. J. Dent. 29, 171–174 (2016).

Tsujimoto, A. et al. Relationships between flexural and bonding properties, marginal adaptation, and polymerization shrinkage in flowable composite restorations for dental application. Polym. (Basel) 13, (2021).

Masouras, K., Silikas, N. & Watts, D. C. Correlation of filler content and elastic properties of resin-composites. Dent. Mater. 24, 932–939 (2008).

Grzebieluch, W., Kowalewski, P., Sopel, M. & Mikulewicz, M. Influence of Artificial Aging on Mechanical Properties of Six Resin Composite Blocks for CAD/CAM Application. Coatings 12, (2022).

Lukomska-Szymanska, M. et al. Evaluation of Physical–Chemical Properties of Contemporary CAD/CAM Materials with Chromatic Transition Multicolor. Materials vol. 16 at (2023). https://doi.org/10.3390/ma16114189

Alzraikat, H., Burrow, M., Maghaireh, G. & Taha, N. Nanofilled Resin Composite properties and clinical performance: a review. Oper. Dent. 43, (2018).

Comba, A. et al. Vickers Hardness and Shrinkage Stress Evaluation of Low and High Viscosity Bulk-Fill Resin Composite. Polymers vol. 12 at (2020). https://doi.org/10.3390/polym12071477

Chun, K. J., Choi, H. H. & Lee, J. Y. Comparison of mechanical property and role between enamel and dentin in the human teeth. J. Dent. Biomech. 5, 1–7 (2014).

Martini Garcia, I. et al. Wear behavior and surface quality of dental bioactive ions-releasing resins under simulated chewing conditions. Front. Oral Heal. 2, 1–12 (2021).

Fuchs, F., Schmidtke, J., Hahnel, S. & Koenig, A. The influence of different storage media on Vickers hardness and surface roughness of CAD/CAM resin composites. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 34, 13 (2023).

Sunbul, H., Al, Silikas, N. & Watts, D. C. Surface and bulk properties of dental resin- composites after solvent storage. Dent. Mater. 32, 987–997 (2016).

Krüger, J., Maletz, R., Ottl, P. & Warkentin, M. In vitro aging behavior of dental composites considering the influence of filler content, storage media and incubation time. PLoS One. 13, e0195160 (2018).

Schmidt, C. & Ilie, N. The effect of aging on the mechanical properties of nanohybrid composites based on new monomer formulations. Clin. Oral Investig. 17, 251–257 (2013).

Chladek, G. et al. Influence of aging solutions on wear resistance and hardness of selected resin-based dental composites. Acta Bioeng. Biomech. 18, 43–52 (2016).

Bauer, H. & Ilie, N. Effects of aging and irradiation time on the properties of a highly translucent resin-based composite. Dent. Mater. J. 32, 592–599 (2013).

Badr, R. M., Al & Hassan, H. A. Effect of immersion in different media on the mechanical properties of dental composite resins. Int. J. Appl. Dent. Sci. 3, 81–88 (2017).

Fonseca, A. S. Q. S., Gerhardt, K. M. F., Pereira, G. D. S., Sinhoreti, M. A. C. & Schneider, L. F. J. Do new matrix formulations improve resin composite resistance to degradation processes? Braz Oral Res. 27, 410–416 (2013).

Szczesio-Wlodarczyk, A., Kopacz, K., Szynkowska-Jozwik, M. I., Sokolowski, J. & Bociong, K. An Evaluation of the Hydrolytic Stability of Selected Experimental Dental Matrices and Composites. Materials vol. 15 at (2022). https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15145055

Pashley, D. H. et al. From dry bonding to water-wet bonding to ethanol-wet bonding. A review of the interactions between dentin matrix and solvated resins using a macromodel of the hybrid layer. Am. J. Dent. 20, 7–20 (2007).

Szczesio-Wlodarczyk, A., Rams, K., Kopacz, K., Sokolowski, J. & Bociong, K. The influence of aging in solvents on Dental cements hardness and Diametral Tensile Strength. Mater. (Basel) 12, (2019).

Alzahrani, B., Alshabib, A. & Awliya, W. The depth of cure, sorption and solubility of dual-cured bulk-fill restorative materials. Mater. (Basel) 16, (2023).

Elfakhri, F., Alkahtani, R., Li, C. & Khaliq, J. Influence of filler characteristics on the performance of dental composites: a comprehensive review. Ceram. Int. 48, (2022).

Par, M. et al. Long-term water sorption and solubility of experimental bioactive composites based on amorphous calcium phosphate and bioactive glass. Dent. Mater. J. 38, 555–564 (2019).

Porenczuk, A. et al. A comparison of the remineralizing potential of dental restorative materials by analyzing their fluoride release profiles. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 28, (2019).

https://www.shofu.com/wp-content/uploads/Beautifil-Flow-Plus-SDS-US-Version-11.pdf

Domarecka, M. et al. Influence of water sorption on the shrinkage stresses of dental composites. J. Stomatol. 69, 412–419 (2016).

Szczesio-Wlodarczyk, A. et al. The influence of low-molecular-weight monomers (TEGDMA, HDDMA, HEMA) on the properties of selected matrices and composites based on Bis-GMA and UDMA. Mater. (Basel Switzerland) 15, (2022).

Leal, J. et al. (ed, P.) Effect of mouthwashes on Solubility and Sorption of Restorative composites. Int. J. Dent. 5865691 2017 (2017).

Prado, V., Santos, K., Fontenele, R., Soares, J. & Vale, G. Effect of over the counter mouthwashes with and without alcohol on sorption and solubility of bulk fill resins. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 12, e1150–e1156 (2020).

Heshmat, H., Hoorizad Ganjkar, M., Sanaei, N., Tabatabaei, S. F. & Kharazifard, M. J. Comparative study of the solubility and Sorption Properties of Resin Modified Glass Ionomer and a Bioactive Liner. J. Res. Dent. Maxillofac. Sci. 7, 125–132 (2022).

Savas, S., Colgecen, O., Yasa, B. & Kucukyilmaz, E. Color stability, roughness, and water sorption/solubility of glass ionomer-based restorative materials. Niger J. Clin. Pract. 22, 824–832 (2019).

Jamel, R. S. Evaluation of Water Sorption and solubility of different Dental cements at different time interval. Int. J. Dent. Sci. Res. 8, 62–67 (2020).

Patroi, D. N. et al. Water sorption and solubility in different environments of composite luting cements: an in vitro study. Mater. Plast. 53, 646–652 (2016).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: M.L.S, S.S., and E.Z.P.; methodology: M.L.S., M.K., and K.O.; formal analysis: M.R., and M.L.S.; investigation: K.O., and M.K.; writing—original draft preparation: M.R., M.L.S. and E.Z.P.; writing—review and editing: M.L.S., and S.S.; visualization: M.R. and L.H.; supervision: M.L.S.; project administration: M.L.S., and M.R.; funding acquisition: M.L.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Radwanski, M., Zmyslowska-Polakowska, E., Osica, K. et al. Mechanical properties of modern restorative “bioactive” dental materials - an in vitro study. Sci Rep 15, 3552 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86595-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86595-7

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Evaluating the physicomechanical characteristics of cetylpyridinium chloride-modified resin-based dental composites following short-and medium-term storage regimes: an in-vitro study

BMC Oral Health (2025)

-

Can lasers replace conventional methods in optimizing bond strength of bioactive materials?

Lasers in Medical Science (2025)