Abstract

Aim of study is to analyze Bromelain’ effects on the most common early complications after BCS (oedema and seroma). From January 2021 to December 2023 a double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial was performed on 114 candidates for BCS at our Academic Unit. Group A received a supplement of Casperome™—Boswellia Phytosome® + Bromelain (CBB) in combination with alpha-lipoic acid + superoxide dismutase + B and D vitamins + centella asiatica. Group B received a supplement of CBB + placebo. Group C received placebo. The therapies were administrated for 30 days. On GEE logistic regression, drugs combination in A seems to be associated with statistical fewer oedema compared with C (P = 0.018 at 1 day and P = 0.002 after 1 month). Comparing B to C, B gained a significative value after 1 month (P = 0.007). On GEE logistic regression, the drugs combination in A has been associated with statistical fewer seroma compared with C (P = 0.009 at 15thpostoperative day and P < 0.001 after 1 month). B vs C reaches significant values 15 day and 1 month after surgery (P = 0.002 and P < 0.001, respectively). The current study is the first analyzing the employment of CBB association with/without neurotrophic agent on prevention of early complications after BCS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) is the leading cause of cancer death in women in Western populations, affecting 1.38 million patients per year1.

Breast-conserving surgery (BCS) (quadrantectomy with or without axillary lymph node dissection, ALND, and radiotherapy) has demonstrated oncological outcomes equivalent to those of mastectomy preserving esthetic outcomes, decreasing operative time, and improving patient satisfaction2.

However, BCS is not free from complications and a recent review reports an overall complication-rate of approximately 20%3,4,5. These can be distinguished as early post-operative complications, occurring within 2 months (oedema, seroma, surgical site infections, hematoma, delayed wound healing, partial skin necrosis) and late complications, after 2 months (fat necrosis, hypertrophic scarring, breast fibrosis) 3,4,5.

Analyzing the incidence of the most common early complications after BCS, breast oedema was reported affecting up to 90% of patients, while seroma up to 85%, albeit under a very broad definition6,7,8.

Early complications, such as breast oedema and seroma, are routinely managed in clinical practice with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)9.

Nevertheless, due to the potential adverse effects of NSAIDs, the use of medications, with anti-edematous and anti-inflammatory properties, is increasingly being promoted. Bromelain is a proteolytic enzyme found in pineapple plants. It promotes the reabsorption of interstitial fluid into blood circulation, increasing tissue permeability via fibrinolysis, with anti-oedema effect10.

Boswellia serrata extracts (Casperome™—Boswellia Phytosome) are preparations derived from a tropical tree (Boswellia serrata) with anti-inflammatory effects usually used in chronic inflammatory diseases. Among the reported properties, there are inhibition of lipoxygenases, proteases, involved in chronic inflammation and the ability to reduce reduce the overexpression of alpha tumor necrosis factor and matrix metallo-proteinases, which play a role in inflammatory processes11.

The effect of these nutraceutical supplements on surgical outcomes has been tested in other areas of surgical practice, while, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study analyzing its effect on the prevention of post-operative pain and management of the most common BCS early complications (oedema and seroma).

This study aims to evaluate the early outcomes after BCS for BC treated with a nutraceutical administration in terms of early onset breast oedema and seroma.

Method

Ethics statement

The study received approval from the Independent Ethical Committee of the University of Bari (Protocol 6422) and was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki of 1975, revised in 2013. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. In addition, all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Trial registration

This study was registered on ClinicalTrials.org with the number NCT04669119, registered on 01/12/2020.

Patient selection and treatments

Patients who underwent BCS for BC at our Academic Unit from January 2021 to December 2023 were enrolled in this double-blind randomized controlled trial.

After diagnosis of BC, supported by ultrasound (US), mammography, and needle biopsy, all patients were followed up by the multidisciplinary team (Breast Care Unit of Policlinic of Bari – BCU). The team proposes the most appropriate therapeutic strategy in accordance with recent guidelines12, providing each patient with the information about surgery and possible post-operative outcomes.

All patients provided informed consent to the surgery and study participation.

Inclusion criteria for the study were the following: gender female, age > 18, tumors < 3 cm, BCS, and a minimum follow-up time of 1 month. History of surgery in the same breast was not cause of exclusion.

Exclusion criteria included: mastectomy; stage IV disease; contraindication to nutraceutical administration; oncoplastic II level volume displacement surgery; use of drain; refusal to complete follow-up or take nutraceuticals and no NSAIDs.

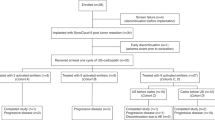

Patients were randomized into 3 groups, using computerized random number generation by Health Authority personnel independently.

Group A received a supplement of Casperome™—Boswellia Phytosome® 200 mg + Bromelain 200 mg (CBB; SIBEN® AGATON SRL, Italy) in combination with a neurotrophic agent supplement (alpha-lipoic acid Retard 400 mg + superoxide dismutase + Vitamin B1, Vitamin B2, Vitamin B6 150% VNR and vitamin D3 21mcg + Centella asiatica 100 mg; KARDINAL V®, AGATON SRL, Italy).

Group B received a supplement of CBB in combination with placebo in the place of neurotrophic agent. Group C (control group) received only administration of placebo.

Both nutraceutical combinations and placebo were administrated 1 a day before lunch for one month and were placed in bottles of identical shape and color (only labeled A, B and C) by an assistant who was uninvolved in the study. Therefore, patients, caregivers, and the outcome assessor were blinded to the received medications.

All groups received a background administration of Paracetamol 1 gr × 3/ day, in the peri-operative period (30 days).

Patients’ general characteristics, demographic data, pre-operative diagnosis, side, operative time, hospital stay, post-operative histology, and early post-operative complications were recorded. Data of post-operative evaluations, including US and pain assessment on the first day (T1), fifteen days (T2) and one month after surgery (T3), were also collected.

Surgical technique

All quadrantectomies were performed, under general anesthesia, by the same experienced surgeon (AG). The technique consists of a mini-elliptical skin incision, radical removal of the tumor containing breast gland tissue to the pectoralis fascia and up to the overlaying skin. When oncologically safe, a subcutaneous resection was performed by periareolar or inframammary incision. In these cases, the subcutaneous coat was prepared keeping the fat layer sufficiently thick (≥ 3 mm) to preserve the blood supply through the sub-dermal vascular plexus. The continuity of the breast disc was restored with sutures, and, finally, skin was aesthetically sutured1.

Sentinel lymph-node biopsy (SLNB) was performed through a separate skin incision using an intraoperative handheld gamma-detection probe was always performed except in case of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) or in patients aged > 80 years and in serious comorbid conditions or where adjuvant systemic and/or RT is unlikely to be affected12.

SLNB was extemporary examined and when positive for metastases patients were submitted to ALND. Drainages were not employed; a compressive bandage was left in place at the end of the operation. Perioperative antibiotics (teicoplanin 400 mg) were given 30 min before the surgical incision and repeated after 12 h. Patients were educated to use a well-fitting, wide-strapped, supportive bra for 2 weeks.

Ultrasound investigation

The US of the breast is carried out by the same experienced sonographer (MM) with a high frequency linear probe (10-13 MHz) with the objective of detecting features of early BCS complications (breast oedema or seroma).

We indicate breast oedema in case of post-operative ultrasound presentation of skin thickening, increased parenchymal echogenicity and interstitial marking13.

The presence of seroma was defined as the accumulation of serous fluid (volume of more than 5 to 20 ml of fluid). Clinically features defining seroma were a palpable, fluctuant, ballotable, or tense region and requires at least one needle aspiration of inflammatory exudate14.

Pain assessment

The post-operative pain evaluation has been assessed by the study of pain intensity and neuropatic origin by Visual analogue scale (VAS) and Douleur Neuropathique 4 (DN4) scale, respectively.

The VAS scale is often used in epidemiologic and clinical research to measure the intensity or frequency of various symptoms. Patient is asked to mark the appropriate point, corresponding at the pain perception, on straight line, 100 mm in length, with one end of the line marked as ‘no pain’, whereas the opposite line end is anchored by ‘worst pain’ (0 to 100) 15,16,17. A score from 10 to 40 was classified as mild pain, from 50 to 60 as moderate pain, and from 70 to 100 as high pain18.

The DN4 scale is a clinician-administered screening questionnaire to help identify neuropathic pain. Different items were analyzed through four questions and items are scored 1 (positive) or 0 (negative). Two items are represented by the results of the questions addressed to the patient (in T1, T2, T3), the other 2 are the result of the medical evaluation carried out at the same times. A total score is calculated as the sum of the 10 items. Scores ≥ 4 out of 10 indicate that neuropathic pain is likely19,20,21.

Statistical analysis

Data analyses were carried out independently by a statistician. The statistical analysis was carried out with STATA14 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA). Descriptive statistics and summary values were analyzed with Student’s t-test for independent samples for continuous values or χ2/Fisher’s exact test for ordinal/binomial variables. A series of univariable logistic Generalized Estimating Equation (GEE) models were fit with empirical standard errors to examine data and calculate the association between early outcomes and the employment of nutraceutical administration. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Descriptive analysis

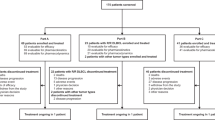

From January 2021 to December 2023, 634 patients underwent breast surgery at our Academic Unit of General Surgery. According to the exclusion criteria, 514 (81.1%) patients were not included in the study: mastectomies (N = 303; 58.9%); stage IV disease (N = 12; 2.3%); contraindication in nutraceutical administration (N = 5; 1%); oncoplastic II level volume displacement surgery (N = 215; 41.8%); use of drain (N = 50; 9.7%); patients who refuse drugs administration (N = 17; 3.3%), patients managed with NSAIDs in perioperative period (N = 12, 2.3%). A total of 120 patients were randomized in 3 groups (A, B, and C) and each consisted of 40 patients. Six patients were lost for no complete follow up during the post operative month. The whole sample analyzed was 114 patients (Group A, N = 39; Group B, N = 37; Group C, N = 38) with a mean age of 56.2 ± 10.2 (range 33 to 78).

In 39 patients CBB + neurotrophic agents (34.2%; group A) were administrated, in 37 patients, CBB + placebo (32.5%; group B) and in 38 patients only double placebo (33.3%; group C—control). The trial design is expressed as a flowchart in Fig. 1.

At admission, 19 patients were affected by palpable mass (16.7%). Among the pre-operative parameters evaluated, 41 patients had cardiological comorbidities (36.3%), 3 patients had pulmonary disease (2.7%), hepatic disease and renal disease was reported in both cases in one patient on admission and ASA score was > 3 in 16 patients (14%). 4 patients had a previous neoplasm in medical history (3.5%). Corticosteroids or immunosuppressant drugs, anticoagulants, previous neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) were reported in 3 (2.7%), in 8 (7.1%), and in 1cases (0.9%), respectively.

At the time of surgery, 51 patients reported BMI > 30 (44.7%). Previous breast surgery was reported in 3.5% of patients (n = 4), while surgical site irradiation was present in 0.9% patients (n = 1).

Table 1 shows demographic data and clinical characteristics of the 3 groups. No significant differences were found in terms of age, BMI, ASA score, comorbidity, previous neck/chest radiation therapy or surgery, and NAC.

The indication for surgery was infiltrative ductal carcinoma (IDC) in 56.1% of patients (N = 64), DCIS in 34.2% (N = 39) and infiltrative lobular carcinoma (ILC) in 9.6% (N = 11).

The mean duration of surgery was 120 min ± 30 (range: 45-180 min), and length of hospitalization was 33 ± 12 (24–72 h).

In 105 (87.5%) cases, surgery consists of quadrantectomy and SLNB and among these, in 4 cases (3.8%) ALND was performed also simultaneously. Five patients (4.2%) were also sent to primary ALND because its clinical and radiological positivity. In 33 patients (27.5%) with DCIS, SLNB was performed for aggressive clinicopathological characteristics (clinically palpable tumor comedo-necrosis and/or high-grade DCIS on diagnostic core biopsy) with an anticipated risk of upstaging to invasive disease on the specimen following histopathological evaluation. No investigation of the SLNB status was required in 10 patients (8.3%).

The perioperative data and histology are summarized in Table 2 and no statistical differences were found among the groups.

There was no perioperative mortality. Overall post-operative morbidity was 18.8%, while post-operative most common early complications in three groups are detailed shown in table Table 3.

Descriptive statistics

Analyzing the oedema, in the comparison among groups based on GEE logistic regression, the use of nutraceutical and neurotrophic agents’ combination in group A was found to be associated with fewer oedema event compared with placebo group, with a statistically significant value P = 0.018 at 1 day and P = 0.002 after 1 month. The group B gained a significant value 1 month after surgery compared to group C (P = 0.007). The comparison between A and B did not show significant differences.

In the comparison among groups, group A appears to be associated with less seroma formation compared with placebo group with a statistical significative value P = 0.009 on 15th post-operative day and P < 0.001 after 1 month. The group B compared to C reaches significant values 15 day and 1 month after surgery (P = 0.002 and P < 0.001, respectively). The comparison between A and B does not highlight statistical significance.

The Vas scale analysis reports mild or no pain (< 40) in 35 cases (89.7%) in group A, in 33 (89.1%) in B and in 31(81.6%) in C after 1 day. After 15 days from surgery, a value < 40 was also noticed in 37 (94.9%), 37 (100%) and 35 (92.1%) patients respectively in group A, B and C. On 30th post-operative day, no patients of group A and B report pain, while 3 (7.9%) in group C experiment an intensity of pain > 40.

The DN4- Scale results < 4 in 36 cases (92.3%) in group A, in all patients in B and 35 (92.1%) in C after 1 day. On 15th post-operative day, 34 (87.2%), 34 (91.9%) and 37 (97.4%) patients respectively in group A, B and C no experiments a significant neuropathic pain. After 1 month, 36 patients (92.3%) in group A, 35 (94.6%) in B, and 36 (94.7%) in C reported a DN4 < 4.

In the analysis of pain with DN4- scale and of VAS scale no significant difference was recorded.

Discussion

Since its introduction in the late 1970s, BCS followed by radiotherapy has been demonstrated to gain the same overall mortality rates achieved with mastectomy, allowing to reach a correct balance between oncological results and cosmetic, functional, and psychosocial advantages22,23. It finds main indication in early-stage BC, DCIS and BC preceded by effective NAC24.

Despite the best surgical efforts, complication rates up to 20% are reported for BCS with a significant emotional distress for patients, sometimes leading to suboptimal aesthetic results, or finally delaying the adjuvant BC treatments3,4,5,25. For all these reasons a correct and prompt management of BCS complications is mandatory even in the perioperative period to avoid early and late complications. Breast oedema and seroma have been described as the most common early complications after BCS and its real incidence has been discussed in literature with a wide variability among reported rates in relation, also, to the type of surgery3,6,26.

The study of breast oedema is complex, with no agreed upon definition of the condition and with a great variability in symptoms and signs quantification (questionnaires, patient-reported rating scales, clinician rating scales and imaging techniques)27. Symptoms of heaviness and redness are commonly associated with breast swelling. These could cause body image issues, fear of injury and pain, embarrassment, anxiety, and relationship difficulties13. Known also as breast lymphedema, it is a subcutaneous swelling caused by excess interstitial fluid in the affected tissues, due to the interruption of lymphatic vessels26. Histological changes include fibrosis, inflammatory features, skin thickening, keratinization, proliferation of lymph and blood vessels and increasing permeability such as clinical and animal experimental models have been demonstrated28. Breast oedema also delays the healing process, which may cause delay the adjuvant therapy, but it has still been under-investigated in the literature. In a recent study27, the measurement of breast tissue thickness by US is defined as “recommended”, contrary, the other different methods are categorized as “promising” as they do not have sufficient evidence for reliability.

Seroma could be defined as an accumulation of serous fluid that develops following breast surgery. Post-surgical wound seroma is very frequent, but not always it is clinically relevant and only a minority requires an intervention8,29. However, also in this case no consistent definition of seroma is present in literature. Some studies, indeed, rely on the need for puncture and aspiration the definition of seroma, while other studies propose US, as it was used in our study, to verify and quantify the seroma volume14. In terms of risks factor, a large dead space appears to contribute to fluid accumulation. Some Author suggested that the presence of a drainage and its duration could influence the seroma formation leading to propose the employment of a low-pressure suction drainage and an earlier drain removal30,31. Other Authors reported seroma rates still like those reported elsewhere, despite the use of drains. In many BCU, other techniques have been used to reduce seroma formation, including compression dressings, arm immobilization, quilting sutures and avoiding the use of electrocautery in dissection without significant impact on symptomatic seroma formation8,29. The pathophysiology and mechanism of seroma formation in breast surgery (BS) remains controversial and no single method of prevention has been shown to be truly effective30.

Among the symptoms reported during the postoperative period, an important role is played by pain and its management becomes crucial. Pain syndrome after breast surgery can be a debilitating condition whit prevalence following definitive management of breast cancer as high as 50%31,32,33,34. The pain could have a moderate severity, neuropathic characteristics, could be in the ipsilateral breast/chest wall, axilla, or arm, and present at least 50% of the time, worsening with shoulder girdle movement35,36. In consideration of these premises, an adequate post-operative pain assessment is essential for a proper and prompt management37. Among all the different methods proposed, VAS scale is one of the most common popular rating scales recommended for assessment of pain intensity. It has been developed to obtain measurements with more variability17,38. Nevertheless, the post-operative pain is often a multidimensional experience: patients may describe in post-operative period sensations referable to neuropathic rather than nociceptive pain, such as “burning” or “pins and needles”. Neuropathic pain is defined as pain related to an injury or disease that affects the somatosensory system. The Douleur Neuropathique 4 (DN4) is a clinician-administered screening questionnaire to help identify neuropathic pain19,20.

The prevention of all these early complications should be the right target of perioperative medicament supplementation.

NSAIDs are being increasingly used to treat post-operative inflammation and pain. Their use seems to reduce pain within 24 h and the chance of nausea and vomiting after surgery. They inhibit cyclooxygenase (COX) enzymes, thereby reducing prostaglandin synthesis and an inflammatory response that causes inflammatory reaction on surgical site. Nevertheless, there is an unclear association between perioperative use of NSAID and an increased risk of in developing a hematoma requiring a redo-surgery for hematoma removal, in patients undergoing elective BS39,40.

In recent years, investigations on natural compounds with therapeutic actions for the treatment of inflammation have increased.

Among these compounds, bromelain is highlighted, as a cysteine protease isolated from the Ananas comosus (pineapple) stem. Bromelain reduced IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α secretion when immune cells were already stimulated in an overproduction conditioned by proinflammatory cytokines, generating a modulation in the inflammatory response through prostaglandins reduction and activation of a cascade reactions that trigger neutrophils and macrophages41. Bromelain, however, shows additional beneficial properties compared to other anti-inflammatory drugs features. The anti-oedema and anti-coagulant effect, and platelet aggregation inhibitory features can be useful in prevention of breast seroma and oedema, as demonstrated in the study. Moreover, it seems that bromelain has the benefit to speed up the healing of wounds. Other studies have, already, showed benefits on surgical site complications and reduction of pain, analyzing the outcomes on another surgical district, especially in orofacial surgery10,41,42,43,44.

Also Boswellia serrata has shown properties in a variety of disease models and human research. Notably, an inhibitory activity on enzymes 5-Lipoxygenase (5-LOX) and COX-1 is known through direct interaction on sites of these enzymes. This derived from a branching tree that grows in the dry regions of India and the Middle East and in recent years, have been established as a multitargeting agent, modulating several targets: 5-LOX, COX-1, Vascular endothelial growth factor, IkappaB kinase, transcription factor Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3, Death receptor 445.

This study allows us to test the use of the combination of Bromelain, Boswellia, and Alpha-lipoic acid in the context of breast surgery. The employment of nutraceutical supplementation seems not to have been studied before in consideration of prevention of these specific complications in patients submitted to BS13.

From the obtained results, it can be emphasized that the employment of nutraceutical and neurotrophic agents’ combination is more effective in the management of early oedema and seroma. Compared with controls, indeed, relevant statistical decrease of oedema was detected in 1st and 30th day after surgery when the CBB plus neurotrophic agents were administered to patients. In the patients treated with only CBB, however, a significant oedema decrease was found at 30th postoperative day in comparison with the placebo group. At the same time, in comparison with controls, statistically significant decrease of seroma incidence was detected in 15th and 30th day after surgery when the CBB plus neurotrophic agents or only CBB were administered to patients. Based on this evidence, a role of nutraceutical administration could be imagined in the prevention or management of early BCS complications as oedema and seroma.

Concerning pain assessment, we analyzed the pain experience reporting data from specifically these two types of scale. Due to the small sample analyzed and the paucity of patients experiencing moderate pain (VAS > 40) and significant neuropathic pain (DN4 > 4), our study fails to show the impact of the use of CBB plus neurotrophic agents in clinical practice both on pain intensity perception and on neuropathic origin. In consideration of this, the employment of a Bromelain supplementation to manage post-operative pain require further analyses.

To the best of our knowledge, the current study is the first analyzing the use of Bromelain and Casperome Boswellia Phytosome, with or without a neurotrophic agent for the prevention of most common early complications after BCS. The limitations of this study include the small numbers of patients and the absence of NSAID arm to compare the effects of bromelain with their use, but we showed an interesting reduction in clinical onset of early oedema and seroma after BCS in comparison with control. Furthermore, the influence of the combination of nutraceuticals on the development of complications in the axillary field, both for ALND and axillary dissection, has not been analyzed in this study.

On other hand, results from this study are in line with a recent review on the anti-inflammatory effects of bromelain suggesting that further standardization is needed to establish doses, supplementation time, and which type of inflammatory condition is indicated46. Indeed, the general effect of bromelain supplementation on inflammation is still under investigation in the surgical field, because of population heterogeneity, doses used, treatment duration, and parameters evaluated in the literature.

Further studies are needed to improve the assessment of nutraceutical supplementation and to standardize its employment in the clinical practice.

Data availability

Data are available upon reasonable request to the authors.

References

Bertozzi, N., Pesce, M., Santi, P. L. & Raposio, E. Oncoplastic breast surgery: Comprehensive review. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 21(11), 2572–2585 (2017).

Benedict, K. C. et al. Oncoplastic breast reduction: A systematic review of post-operative complications. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 11(10), e5355. https://doi.org/10.1097/GOX.0000000000005355 (2023).

Haloua, M. H. et al. A systematic review of oncoplastic breast-conserving surgery: Current weaknesses and future prospects. Ann. Surg. 257(4), 609–620. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182888782 (2013).

Casella, D. et al. Portable negative pressure wound dressing in oncoplastic conservative surgery for breast cancer: A valid ally. Medicina (Kaunas). 59(10), 1703. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59101703 (2023).

Clough, K. B. Oncoplastic techniques allow extensive resections for breast-conserving therapy of breast carcinomas. Ann. Surg. 237(1), 26–34. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000658-200301000-00005 (2003).

Verbelen, H., Gebruers, N., Beyers, T., De Monie, A. C. & Tjalma, W. Breast edema in breast cancer patients following breast-conserving surgery and radiotherapy: A systematic review. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 147(3), 463–471. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-014-3110-8 (2014) (epub 2014 Aug 28).

Knowles, S. et al. An alternative to standard lumpectomy: A 5-year case series review of oncoplastic breast surgery outcomes in a Canadian setting. Can. J. Surg. 63(1), E46–E51. https://doi.org/10.1503/cjs.003819 (2020).

Taylor, J. C., Rai, S., Hoar, F., Brown, H. & Vishwanath, L. Breast cancer surgery without suction drainage: The impact of adopting a “no drains” policy on symptomatic seroma formation rates. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 39(4), 334–338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2012.12.022 (2013) (epub 2013 Feb 4).

Costanzo, D. & Romeo, A. Surgical site infections in breast surgery - A primer for plastic surgeons. Eplasty. 23, e18 (2023).

Babazade, H., Mirzaagha, A. & Konarizadeh, S. The effect of bromelain in periodontal surgery: A double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial. BMC Oral Health. 23(1), 286. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-023-02971-7 (2023).

Ferrara, T., De Vincentiis, G. & Di Pierro, F. Functional study on Boswellia phytosome as complementary intervention in asthmatic patients. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 19(19), 3757–3762 (2015).

National Comprehensive Cancer Network. CCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Breast Cancer. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast.pdf (2024). Accessed 26 Mar 2024

Todd, M. Identification, assessment and management of breast oooedema after treatment for cancer. Int. J. Palliat. Nurs. 23(9), 440–444. https://doi.org/10.12968/ijpn.2017.23.9.440 (2017).

Kuroi, K. et al. Pathophysiology of seroma in breast cancer. Breast Cancer 12(4), 288–293. https://doi.org/10.2325/jbcs.12.288 (2005).

Price, D. D., McGrath, P. A., Rafii, A. & Buckingham, B. The validation of visual analogue scales as ratio scale measures for chronic and experimental pain. Pain 17(1), 45–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3959(83)90126-4 (1983).

Price, D. D., Bush, F. M., Long, S. & Harkins, S. W. A comparison of pain measurement characteristics of mechanical visual analogue and simple numerical rating scales. Pain. 56(2), 217–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3959(94)90097-3 (1994).

Sung, Y. T. & Wu, J. S. The Visual Analogue Scale for rating, ranking and paired-comparison (VAS-RRP): A new technique for psychological measurement. Behav. Res. Methods 50(4), 1694–1715. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-018-1041-8 (2018).

Reed, M. D. & Van Nostran, W. Assessing pain intensity with the visual analog scale: A plea for uniformity. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 54(3), 241–244. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcph.250 (2014) (epub 2014 Jan 23).

Ferraro, M. C. & McAuley, J. H. Clinimetrics: Douleur neuropathique en 4 questions (DN4). J. Physiother. 70(3), 238–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphys.2024.02.010 (2024) (epub 2024 Mar 25).

Attal, N., Bouhassira, D. & Baron, R. Diagnosis and assessment of neuropathic pain through questionnaires. Lancet Neurol. 17(5), 456–466. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30071-1 (2018) (epub 2018 Mar 26).

Aho, T., Mustonen, L., Kalso, E. & Harno, H. Douleur Neuropathique 4 (DN4) stratifies possible and definite neuropathic pain after surgical peripheral nerve lesion. Eur. J. Pain. 24(2), 413–422. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejp.1498 (2020) (epub 2019 Nov 12).

Gurrado, A. et al. Mastectomy with one-stage or two-stage reconstruction in breast cancer: Analysis of early outcomes and patient’s satisfaction. Updates Surg. 75(1):235–243 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13304-022-01416-0. epub 2022 Nov 19. Erratum in: Updates Surg. 2022 Dec 17.

Semprini, G. et al. Oncoplastic surgery and cancer relapses: Cosmetic and oncological results in 489 patients. Breast. 22(5), 946–951. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2013.05.008 (2013) (epub 2013 Jul 9).

Kaur, N. et al. Comparative study of surgical margins in oncoplastic surgery and quadrantectomy in breast cancer. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 12(7), 539–545. https://doi.org/10.1245/ASO.2005.12.046 (2005) (Epub 2005 May 10).

Donahue, P.M.C., MacKenzie, A., Filipovic, A. & Koelmeyer, L. Advances in the prevention and treatment of breast cancer-related lymphedema. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 200(1):1–14 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-023-06947-7. Epub 2023 Apr 27.

Cornacchia, C. et al. Breast edema after conservative surgery for early-stage breast cancer: A retrospective single-center assessment of risk factors. Lymphology. 55(4), 167–177 (2022).

Fearn, N., Llanos, C., Dylke, E., Stuart, K. & Kilbreath, S. Quantification of breast lymphoedema following conservative breast cancer treatment: A systematic review. J. Cancer Surviv. 17(6):1669–1687 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-022-01278-w. epub 2022 Oct 27.

Nakagawa, A. et al. Histological features of skin and subcutaneous tissue in patients with breast cancer who have received neoadjuvant chemotherapy and their relationship to post-treatment edema. Breast Cancer 27(1), 77–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12282-019-00996-x (2020) (epub 2019 Jul 25).

Ebner, F. et al. Seroma in breast surgery: All the surgeons fault?. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 298(5), 951–959. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-018-4880-8 (2018) (epub 2018 Sep 8).

Agrawal, A., Ayantunde, A. A. & Cheung, K. L. Concepts of seroma formation and prevention in breast cancer surgery. ANZ J. Surg. 76(12), 1088–1095. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1445-2197.2006.03949.x (2006).

Cregan, P. Review of concepts of seroma formation and prevention in breast cancer surgery. ANZ J. Surg. 76(12), 1046. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1445-2197.2006.03939.x (2006).

Stubblefield, M.D. & Custodio, C.M. Upper-extremity pain disorders in breast cancer. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 87(3 Suppl 1):S96–9; quiz S100–1 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2005.12.017.

Juhl, A.A., Christiansen, P. & Damsgaard, T.E. Persistent pain after breast cancer treatment: A questionnaire-based study on the prevalence, associated treatment variables, and pain type. J. Breast Cancer. 19(4):447–454 (2016). https://doi.org/10.4048/jbc.2016.19.4.447. epub 2016 Dec 23.

Chen, V. E. et al. Post-mastectomy and post-breast conservation surgery pain syndrome: A review of etiologies, risk prediction, and trends in management. Transl. Cancer Res. 9(Suppl 1), S77–S85. https://doi.org/10.21037/tcr.2019.06.46 (2020).

Waltho, D. & Rockwell, G. Post-breast surgery pain syndrome: Establishing a consensus for the definition of post-mastectomy pain syndrome to provide a standardized clinical and research approach - A review of the literature and discussion. Can. J. Surg. 59(5), 342–350. https://doi.org/10.1503/cjs.000716 (2016).

Beederman, M. & Bank, J. Post-breast surgery pain syndrome: Shifting a surgical paradigm. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 9(7), e3720. https://doi.org/10.1097/GOX.0000000000003720 (2021).

Burton, A. W., Chai, T. & Smith, L. S. Cancer pain assessment. Curr. Opin. Support Palliat. Care. 8(2), 112–116. https://doi.org/10.1097/SPC.0000000000000047 (2014).

Wewers, M. E. & Lowe, N. K. A critical review of visual analogue scales in the measurement of clinical phenomena. Res. Nurs. Health 13(4), 227–236. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.4770130405 (1990).

Klifto, K.M., Elhelali, A., Payne, R.M., Cooney, C.M., Manahan, M.A., Rosson, G.D. Perioperative systemic nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in women undergoing breast surgery. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 11(11), CD013290. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD013290.pub2 (2021).

Cawthorn, T. R., Phelan, R., Davidson, J. S. & Turner, K. E. Retrospective analysis of perioperative ketorolac and postoperative bleeding in reduction mammoplasty. Can. J. Anaesth. 59(5), 466–472. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-012-9682-z (2012) (epub 2012 Mar 21).

Alves Nobre, T. et al. Bromelain as a natural anti-inflammatory drug: A systematic review. Nat. Prod. Res. 27, 1–14 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1080/14786419.2024.2342553. epub ahead of print.

Bhoobalakrishnan, M. S., Rattan, V., Rai, S., Jolly, S. S. & Malhotra, S. Comparison of efficacy and safety of bromelain with diclofenac sodium in the management of postoperative pain and swelling following mandibular third molar surgery. Adv. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 3, 100112 (2021).

Mameli, A., Natoli, V. & Casu, C. Bromelain: An overview of applications in medicine and dentistry. Biointerface Res. Appl. Chem. 11, 8165–8170 (2020).

de Souza, G. M., Fernandes, I. A., Dos Santos, C. R. R. & Falci, S. G. M. Is bromelain effective in controlling the inflammatory parameters of pain, ooedema, and trismus after lower third molar surgery? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Phytother. Res. 33(3), 473–481. https://doi.org/10.1002/ptr.6244 (2019) (epub 2018 Nov 28).

Suther, C. et al. Dietary Boswellia serrata acid alters the gut microbiome and blood metabolites in experimental models. Nutrients. 14(4), 814. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14040814 (2022).

Pereira, I. C. et al. Bromelain supplementation and inflammatory markers: A systematic review of clinical trials. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 55, 116–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnesp.2023.02.028 (2023) (epub 2023 Mar 2).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Sgaramella LI, Pasculli A, Clemente L, Prete FP, and Gurrado A. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Sgaramella LI and Gurrado A. Moschetta M, Puntillo F, Dicillo P, Maruccia M, Mastropasqua M, Piombino M, Resta N, Rubini G, Serio G, Stucci S, Giudice G and Testini M commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors of BCU PoliBa group read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sgaramella, L.I., Pasculli, A., Moschetta, M. et al. Randomized controlled trial of bromelain and alpha-lipoic acid in breast conservative surgery. Sci Rep 15, 4899 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86651-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86651-2