Abstract

Adeno-associated virus (AAV) mediated gene therapy is advancing and needs a noninvasive imaging tool to evaluate its effective targeting, biodistribution and clearance for precise use in humans. In this study, two serotypes of AAVs, AAV9-CMV-fLuc, and a brain targeting variant, AAVBR1-CMV-fLuc, are directly radiolabeled with the positron emission tomography (PET) radioisotope, 89Zr. A radiolabeling synthon, [89Zr]Zr-DFO-Bn-NCS or [89Zr]Zr-DBN, was employed for the direct radiolabeling of AAVs, which enables tracking of AAVs by PET imaging for up to 18 days post-injection. The 89Zr radiolabeled AAVs were administered to BALB/c mice via tail vein and assessed for their biodistribution at various time points up to day 18 post-injection. Imaging of AAVs was followed by ex-vivo biodistribution at day 18, or luciferase imaging at 3rd week or > 30 days post-injection. The two serotypes showed differences in their biodistribution and trafficking in mice as early as 10 min post-injection. The brain targeting serotype, [89Zr]Zr-AAVBR1-CMV-fLuc, showed significantly higher uptake in the brain as compared to [89Zr]Zr-AAV9-CMV-fLuc. The luciferase expression-based infection profile correlated with both PET imaging and ex-vivo biodistribution data. The developed methodology provides a noninvasive approach to image the pharmacokinetics of AAVs in a longitudinal manner and renders a selection of specific AAV serotypes for tissue/organ specific targeting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) are non-enveloped viruses with an icosahedral capsid protein shell encapsulating a single stranded DNA genome ( ̴ 4.7 kilobases)1. The capsid protein shell is composed of 60 monomeric viral protein (VP) subunits, VP1, VP2, and VP3, in the ratio of 1:1:10, respectively1,2. The capsid protein shell provides shielding to the AAV genome and determines tissue tropism of administered AAVs in the body2. After homing to an organ or tissue, the capsid protein facilitates internalization of the AAVs into the cells of the host tissue and regulates subsequent intracellular trafficking of AAVs to the nucleus of the cell2. The intracellular trafficking of AAVs involves the binding of AAVs to the cell surface receptors followed by internalization via endocytosis and subsequent entry into the nucleus1,2 as summarized in Fig. 1. AAVs uncoat themselves in the nucleus and release their genome into the host nucleus. There is only ~ 0.1% probability of the AAV genome integrating into the host cell genome (chromosomal integration)3. The AAV genome predominantly remains non-integrated in the host nucleus in the form of extrachromosomal episomes3. There are at least 12 natural serotypes of AAV (AAV 1–12) and all of them are considered non-pathogenic2. Therefore, their DNA genomes are amenable to genetic modification and provide a safe vehicle for gene therapy applications2. To date, over 100 variants of natural AAVs are known and about 149 clinical trials are reported to treat several diseases using therapeutic genes2,4. So far, the Food and Drug Administration of the United States of America (FDA) has approved three gene products based on recombinant AAV-derived vectors that include Luxturna (AAV2), Zolgensma (AAV9) and Hemgenix (AAV5), to treat eye disease, spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) and hemophilia, respectively2.

To treat single gene brain diseases, there is a high interest in identification and application of appropriate therapeutic AAVs, where AAVs can be administered systemically as opposed to the direct injection into the brain5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13. Various AAVs with improved CNS transduction efficiency have been identified in both engineered AAV variants (AAV.PHP.eB6,7 and AAV.PHP.B6,7) and natural serotype like AAVrh108,9.

Both these AAV variants are currently being tested in different animal species to understand their pharmacokinetics (PK)5,6,7,8,9. Aside from the above two variants, another variant of AAV2, known as AAVBR1 has shown promising results as a brain targeting AAV10,11,12,13. In fact, AAVBR1 has shown selectivity for the brain endothelium and its ability to cross the blood brain barrier after systemic delivery, making it highly valuable for treating various brain diseases10,11,12,13.

Although significant progress has been made in gene therapies using AAVs, immune responses are reported in patients undergoing gene therapies14. These immune responses could be associated with pre-existing immunity to AAVs, which are due to prior exposure to wild type AAVs that are prevalent in the human population, or due to an innate or adaptive response that manifests within hours or days after the administration of therapeutic AAVs14. To resolve these issues, during development, the AAVs can be altered through genetic engineering by insertion of different non-immunogenic therapeutic genes in the viral genome and/or through capsid engineering by mutating the surface exposed amino acid. These modifications may impart an immune evasion ability, transduction efficiency and organ tropism to engineered AAVs2.

Developing an effective targeted therapy using AAVs that would preferentially home to a particular organ or tissue needs a noninvasive monitoring tool, which could shed light on their on-site or off-site accumulation, biodistribution and clearance profile. Currently, there is a known technology that could track the fate of AAVs genomes in host cells using a fluorescence in-situ hybridization (FISH) DNA probe, but it requires a fixed tissue specimen and biopsy of the area of interest15. Given the need for multiple biopsies, FISH technology is not suited for many longitudinal studies. In contrast, a non-invasive imaging-based tracking of AAVs would be more suited for longitudinal studies. To accomplish noninvasive imaging of AAVs, reporter gene based imaging strategies are being developed employing positron emission tomography (PET), single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), molecular/functional magnetic resonance imaging (m/fMRI) and optical imaging modalities (fluorescence, bioluminescence, Cerenkov luminescence, photoacoustic imaging, Raman imaging etc.)16,17,18,19. An alternative strategy for tracking AAVs could employ tagging of AAVs capsid protein with fluorescent dyes20,21, nanoparticles22 and 124Iodine23 or 64Copper24 radioisotopes, and provide direct in vivo mapping of administered AAVs without genetic modifications16.

Among the various imaging modalities, optical imaging has a limitation with tissue penetration range, which poses the main obstacle for its clinical translation25,26,27,28. MRI and CT imaging provide high-resolution anatomical information but are restricted by their lower sensitivity (mM concentrations of contrast agents)29,30. Radionuclide imaging with PET/SPECT offers quantitative measurement of biological processes or change in biological processes for disease diagnosis, prognosis and therapeutic monitoring with high sensitivity31. Moreover, of the two, PET offers higher sensitivity over SPECT and is an unequivocally superior imaging modality when combined with CT/MRI for co-registration of anatomical location32. Previously, [18F]FDG has been used to map viral infection associated inflammation caused by COVID-1933 and HIV34 in humans. It is to be noted that [18F]FDG is only a surrogate tracer for assessing indirect viral biodistribution as it visualizes the high glucose uptake regions in response to inflammation associated with the viral infection. As such, [18F]FDG imaging of viruses is non-specific as it does not elude the physical biodistribution of the administered viruses, but rather the inflammation, which may or may not be associated with the viruses. Therefore, there is an unmet need for PET-based viral imaging and development of organ-specific targeting of viruses to further advance the gene therapy.

To assess the biodistribution of administered viruses, two PET radioisotopes, 124I (t1/2 = 4.17 days) and 64Cu (t1/2 = 12.7 h), have been investigated23,24. Kothari et al. investigated the pharmacokinetics of [124I]I-AAV.rh10 in male CD-1 mice by PET imaging after intraparenchymal injection in the left striatum for up to 16 days post-injection23. The PET signal from 124I-radiolabeled AAV.rh10 were visible in the brain for up to 8 days post-injection. In another study, Seo et al. demonstrated brain mapping using a novel 64Cu-radiolabeled AAV9 capsid variant, AAV.PHP.eB, and compared it with AAV9 serotype upon systemic injection in C57BL/6 mice24. Based on PET analysis at 30 min post-injection, the brain uptake of 64Cu-radiolabeled AAV.PHP.eB (10% ID/cc) was significantly higher than AAV9 (< 1% ID/cc), and the affinity of 64Cu-radiolabeled AAV.PHP.eB was reportedly 20-fold higher than AAV9 towards the brain endothelium24. Interestingly, reduced brain uptake of AAV.PHP.eB was found in a different mouse strain, BALB/c, when analyzed over 21 h, possibly due to the lack of brain endothelial cell receptor LY6A which is essential for the uptake of AAV.PHP.B35,36. This study underlines the importance of PET imaging in identifying relevant preclinical models when studying the in vivo characteristics of different AAVs.

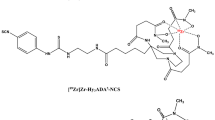

Recently developed 124I (t1/2 = 4.17 days) labeled viral imaging offers longitudinal imaging, but its high mean positron energy (819 keV) results in suboptimal image quality, whereas 64Cu based viral imaging provides better image quality, but is limited by its shorter half-life of 12.7 h. An ideal viral PET imaging probe should have a longer half-life (3–4 days) for longitudinal imaging and a lower mean positron energy (< 400 keV) to produce high resolution images37 for mapping the site-specific uptake, biodistribution, trafficking and clearance profile of the administered viruses. Our group has developed a strategy to radiolabel AAVs with the positron emitter 89Zr (t1/2= 78.41 h or 3.3 d), using a ready-to-use labeling synthon, [89Zr]Zr-DFO-Bn-NCS, also known as [89Zr]Zr-DBN38,39. In this direct radiolabeling approach, [89Zr]Zr-DBN forms a stable covalent thiourea linkage with primary amines of the capsid proteins of AAVs. The relatively longer half-life of 89Zr allows for the assessment of biodistribution, trafficking and clearance profile of radiolabeled AAVs for several days to weeks post-administration with superior image quality than 124I labeled AAVs. In this study, we radiolabeled AAV9-CMV-fLuc and the brain targeting AAV2 variant, AAVBR1-CMV-fLuc with 89Zr using [89Zr]Zr-DBN38,39. The radiolabeled AAVs were administered to healthy BALB/c mouse via tail vein. The biodistribution of radiolabeled AAVs were assessed using PET imaging at various time points up to 18 days post-intravenous delivery, followed by luciferase imaging to identify AAV mediated luciferase expression in various organs.

Results and discussion

Direct radiolabeling of viruses with [89Zr]Zr-DBN

For direct radiolabeling of viruses with [89Zr]Zr-DBN38,39, the PET radioisotope 89Zr was successfully chelated to DFO-Bn-NCS to form [89Zr]Zr-DBN with a chelation efficiency of 86.07 ± 8.61% (n = 5). The specific activity of [89Zr]Zr-DBN used for virus radiolabeling was 51.84 ± 24.96 GBq/µmol (1.40 ± 0.67 Ci/µmol) (n = 5). Following synthesis of [89Zr]Zr-DBN, two different serotypes of AAV, AAV9-CMV-fLuc (5.32 × 1012 virus particles) and AAVBR1-CMV-fLuc (2.32 × 1012 virus particles), were exposed to [89Zr]Zr-DBN at pH 9.0 to facilitate a reaction between the isothiocyanate group of [89Zr]Zr-DBN and the primary amines present on the AAV capsid proteins. The radiochemical yield (RCY) was assessed after 30 min by r-TLC. The representative chromatograms of r-TLCs of 89Zr, [89Zr]Zr-DBN, [89Zr]Zr-AAV9-CMV-fLuc and [89Zr]Zr-AAVBR1-CMV-fLuc are summarized in Fig. S1-S4 of the supplementary information. After size exclusion purification, both [89Zr]Zr-AAV9-CMV-fLuc and [89Zr]Zr-AAVBR1-CMV-fLuc showed > 95% radiochemical purities (Fig. S3-S4) and the purified products were used for SDS-PAGE, autoradiography and in vivo studies. The synthesis of [89Zr]Zr-AAV9-CMV-fLuc and [89Zr]Zr-AAVBR1-CMV-fLuc from [89Zr]Zr-DBN gave a RCY of 24.97 ± 7.29% (n = 2) and 20.37 ± 0.07% (n = 2), respectively. Obtained yields were found to be higher than the radiolabeling yield reported by Kothari et al. for AAVrh.10CLN2 using 124I using iodogen (10–18%) or Bolton-Hunter (1-4.5%) methods23. Additionally, the yield for radiolabeling AAVs with 64Cu using PEGylated muti-chelator (NOTA8) method reported by Seo et al.24 was also lower than the [89Zr]Zr-DBN based virus radiolabeling method. Seo et al.24, reported a RCY of 2.2% for [64Cu]Cu-AAV9, 6.6% for [64Cu]Cu-AAV9-TC and 7.5 ± 6.0% for [64Cu]Cu-AAVPHP.eB only24.

The [89Zr]Zr-DBN mediated radiolabeling of AAVs was achieved with a molar activity of 4743.77 GBq/µmol (128.21 Ci/µmol) for [89Zr]Zr-AAV9-CMV-fLuc and 5145.96 GBq/µmol (139.08 Ci/µmol) for [89Zr]Zr-AAVBR1-CMV-fLuc (high molar activity preparation), which were used in animal studies. Kothari et al.23 was able to use Iodogen method and Bolton-Hunter method to radiolabel AAVrh.10CLN2 with 124I but molar activity of [124I]I- AAVrh.10CLN2 was not reported. In the case of 64Cu radiolabeling, Seo et al.24 reported radiolabeling of AAV9 and AAV.PHP.eB with 64Cu using PEGylated multi-chelator (NOTA8) functionalized with trans cyclooctene (TCO) or maleimide (MI) groups. Although the multi-NOTA chelator (NOTA8) approach showed ~ 10-fold higher molar radioactivity than the single NOTA chelator in their study, the molar activity of [64Cu]Cu-AAV9, [64Cu]Cu-AAV9-TC and [64Cu]Cu-AAV.PHP.eB were not reported. Moreover, the multi-chelator approach would cause significant change to the original AAV structure24.

SDS-PAGE and autoradiography

The radiolabeling of AAV9-CMV-fLuc and AAVBR1-CMV-fluc with [89Zr]Zr-DBN was confirmed by SDS-PAGE followed by silver staining and 89Zr autoradiography of the same gel (Fig. 2).

To calculate the molar activity of the radiolabeled viral particles, we counted the amount of radioactivity (GBq/MBq) present in the purified radiolabeled AAVs fraction and also applied Avogadro’s number concept40 to calculate the number of moles of viral particle present in the purified fraction. The number of viral particles in the purified fraction was calculated by qPCR after radiolabeling and size-exclusion purification. Overall, 0.0174 GBq (0.47 mCi) of the AAV9-CMV-fLuc having 2.93 × 1012 virus particles and 0.0021 GBq (0.0561 mCi) of AAVBR1-CMV-fLuc having 1.20 × 1012 virus particles were recovered as pure fractions after radiolabeling (Supplementary Information, Table S1). If 6.022 × 1023 virus particles are present in 1.0 mol of virus preparation40, therefore, 2.93 × 1012 VP would be 4.86 × 10− 12 mol or 4.86 pmol of AAV9-CMV-fLuc. Thus, the decay-corrected molar activity of [89Zr]Zr-AAV9-CMV-fLuc was 3574.15 GBq/µmol (96.60 Ci/µmol). Similarly, for [89Zr]Zr-AAVBR1-CMV-fLuc (low molar activity preparation), 1.20 × 1012 virus particles were recovered after purification with decay corrected 0.0021 GBq (0.0564 mCi) radioactivity. Thus, the decay-corrected molar activity of [89Zr]Zr-AAVBR1-CMV-fLuc was 1041.65 GBq/µmol (28.15 Ci/µmol). On analyzing the relative distribution of radioactivity in capsid proteins bands (VP1: VP2: VP3) on a SDS-PAGE autoradiograph, it was observed that the distribution of radioactivity was not as expected for viral particle composition of 1:1:10 for the VP1: VP2: VP3 bands but were in approximately 3.1: 2.6: 4.3 proportion for [89Zr]Zr-AAV9-CMV-fLuc and 3.5: 2.9: 3.6 proportion for [89Zr]Zr-AAVBR1-CMV-fLuc. Based on the observed radioactivity distribution, it appears that lysine residues on VP1 and VP2 capsid proteins are more reactive or available for radiolabeling with [89Zr]Zr-DBN, as compared to the VP3 capsid protein. Obtained results are also summarized in Fig. 3.

PET imaging and ex vivo biodistribution studies

Although the kinetics of AAVs have been studied by other groups using PET imaging of radiolabeled AAVs with both shorter lived 64Cu (t1/2 = 12.7 h) and longer lived 124I (t1/2 = 4.17 days) isotopes, there were still gaps in the previous studies. Both [64Cu]Cu-AAV.PHP.eB24 and [64Cu]Cu-AAV924 allowed the tracking of AAVs for up to 21 h in C57BL/6 mice after tail vein injection. The pharmacokinetics of [124I]I-AAVrh.10 was assessed up to 16 days after injection, however, the administration was performed locally into the left striatum of CD-1 mice, not systemically23. Therefore, so far, a PET imaging-based pharmacokinetic assessment of AAVs beyond 21 h has not been performed systemically and previously 64Cu-labeled AAVs had multi-chelators, which could have caused significant variation in the pharmacokinetics of the 64Cu-labeled AAVs compared to the original AAVs.

As a proof of concept, herein we designed [89Zr]Zr-DBN mediated direct radiolabeling of AAVs with a minimal change in the AAVs structure and performed PET imaging of the radiolabeled AAVs for up to 18 days post-systemic injection. The pharmacokinetics of the systemically administered [89Zr]Zr-AAV9-CMV-fLuc and [89Zr]Zr-AAVBR1-CMV-fLuc were assessed in BALB/c mice at multiple time points, at 5 min, 10 min, 15 min, 2 h, 4 h, 24 h, 48 h, 72 h, day 4, day 6, day 7, day 12, day 14 and day 18 post-injection. In this study, two different serotypes of AAV, AAV9 and AAVBR1, were selected with their different organ tropism. Among the two, AAV9 is a general AAV, targeting various organs, whereas AAVBR1 is a known brain targeting AAV. Selecting different AAVs allowed us to evaluate the PET imaging capability to assess the biodistribution of AAVs with different organ tropism.

The administered AAVs are known to exhibit a biphasic blood clearance profile with a rapid blood clearance in the first 30 min and a slower clearance for up to 24 h post-injection41. The blood clearance of the administered AAVs were assessed by measuring the percentage of radioactivity in the blood pool of the heart in the acquired PET scans. Observed results confirmed the biphasic blood clearance of [89Zr]Zr-AAV9-CMV-fLuc and [89Zr]Zr-AAVBR1-CMV-fLuc in BALB/c mice, showing a faster clearance before 30 min and a slower clearance thereafter until 24 h post-injection (Fig. 4A and B). After 24 h, very slow clearance of [89Zr]Zr-AAV9-CMV-fLuc and [89Zr]Zr-AAVBR1-CMV-fLuc were observed from the blood pool until day 18 (Fig. 4C).

Overtime clearance of [89Zr]Zr-AAV9-CMV-fLuc and [89Zr]Zr-AAVBR1-CMV-fLuc from the heart of the BALB/c mice assessed by PET imaging. A Graph showing faster of clearance of [89Zr]Zr-AAV9-CMV-fLuc and [89Zr]Zr-AAVBR1-CMV-fLuc from the blood during the first 30 min post-injection B Graph showing biphasic blood clearance of [89Zr]Zr-AAV9-CMV-fLuc and [89Zr]Zr-AAVBR1-CMV-fLuc with a faster clearance during first 30 min followed by a slower clearance until 72 h post-injection. C Graph showing stable PET signal in the heart after 72 h post injection until 18th day. Data is derived from measuring the SUV in the heart at multiple time points over 18 days post-injection.

In terms of AAV distribution among the organs, [89Zr]Zr-AAV9-CMV-fLuc and [89Zr]Zr-AAVBR1-CMV-fLuc were found in the liver, lungs, spleen, kidney and vertebra as early as 5 min post-injection as assessed by PET image analysis (Tables 1 and 2). At 5 min post-injection, there were no significant differences in uptakes of [89Zr]Zr-AAV9-CMV-fLuc and [89Zr]Zr-AAVBR1-CMV-fLuc in the brain, lungs, liver, kidneys, spleen, gut, vertebra, bones and muscle (Tables 1 and 2). However, at 10 min post-injection, [89Zr]Zr-AAV9-CMV-fLuc and [89Zr]Zr-AAVBR1-CMV-fLuc showed a significant difference in their uptakes in the brain with a SUV of 0.61 ± 0.13 for AAV9 and 1.02 ± 0.29 for AAVBR1, with a p value of 0.01 (Tables 1 and 2, and Fig. 5). A similar trend was noticed in the vertebra at 10 min post-injection with a SUV of 1.76 ± 0.49 for AAV9 and 2.30 ± 0.33 for AAVBR1, with a p value of 0.03, demonstrating a significant difference in their uptakes (Tables 1 and 2). This significant difference in uptake of [89Zr]Zr-AAV9-CMV-fLuc and [89Zr]Zr-AAVBR1-CMV-fLuc in the brain and vertebra sustained even at 15 min post-injection (Tables 1 and 2). The brain and vertebra continued to show a higher SUV with [89Zr]Zr-AAVBR1-CMV-fLuc than [89Zr]Zr-AAV9-CMV-fLuc even after 15 min post-injection until 24 h post injection (Tables 1 and 2; Fig. 5).

A Representative sagittal PET images showing biodistribution of [89Zr]Zr-AAVBR1-CMV-fLuc (AAVBR1) and [89Zr]Zr-AAV9-CMV-fLuc (AAV9) in the brain (open circle) of BALB/c mice at different time points post-injection (up to 48 h post-injection) and B Graph showing uptake of [89Zr]Zr-AAVBR1-CMV-fLuc and [89Zr]Zr-AAV9-CMV-fLuc in the brain at different time points post-injection (up to 48 h post-injection).

At 2 h post-injection, additional organs and tissues like the muscle and gut started showing significant differences in uptakes between [89Zr]Zr-AAV9-CMV-fLuc and [89Zr]Zr-AAVBR1-CMV-fLuc. [89Zr]Zr-AAV9-CMV-fLuc showed higher uptake in the gut with a SUV of 3.14 ± 0.68 for AAV9 and 1.64 ± 0.78 for AAVBR1, (p value = 0.01) at 2 h post injection. [89Zr]Zr-AAVBR1-CMV-fLuc showed higher uptake in muscle with a SUV of 0.55 ± 0.16, than [89Zr]Zr-AAV9-CMV-fLuc having a SUV of 0.34 ± 0.11 (p value = 0.02, Tables 1 and 2, and Fig. 6). At 4 h post-injection, no significant differences in uptakes were observed in muscles of the two serotypes, but the brain, gut and vertebra continued to show differences in uptakes of the two serotypes (Tables 1 and 2). [89Zr]Zr-AAVBR1-CMV-fLuc showed a higher uptake in the brain with SUV of 0.83 ± 0.25 as compared to 0.39 ± 0.26 for [89Zr]Zr-AAV9-CMV-fLuc (p value = 0.01).

A Representative sagittal PET maximum intensity projection (MIP) images showing the distribution of [89Zr]Zr-AAVBR1-CMV-fLuc (AAVBR1) and [89Zr]Zr-AAV9-CMV-fLuc (AAV9) in different organs of BALB/c mice at different time points post-injection (up to 48 h post-injection) and B Graph showing the uptake of [89Zr]Zr-AAVBR1-CMV-fLuc and [89Zr]Zr-AAV9-CMV-fLuc in the liver at different time points post-injection (up to 48 h post-injection). B = brain, H = heart, Lu = lungs, Li = liver, G = gut and V = vertebrate.

At 4 h post-injection, [89Zr]Zr-AAVBR1-CMV-fLuc showed a higher uptake (2.33 ± 0.68 SUV) in vertebra as compared to [89Zr]Zr-AAV9-CMV-fLuc (1.41 ± 0.11 SUV, p value = 0.01, Tables 1 and 2). However, at the same 4 h post-injection time point, the uptake of [89Zr]Zr-AAVBR1-CMV-fLuc (1.01 ± 0.44 SUV) in the gut was lower as compared to [89Zr]Zr-AAV9-CMV-fLuc (3.33 ± 1.13 SUV, p value = 0.001) demonstrating difference in biodistribution of [89Zr]Zr-AAVBR1-CMV-fLuc and [89Zr]Zr-AAV9-CMV-fLuc.

At 24 h post-injection, [89Zr]Zr-AAVBR1-CMV-fLuc showed a higher uptake than the [89Zr]Zr-AAV9-CMV-fLucin the lungs, kidneys, muscle, brain and vertebra (Tables 1 and 2). However, [89Zr]Zr-AAV9-CMV-fLuc showed significantly higher uptake than [89Zr]Zr-AAVBR1-CMV-fLuc in bones and spleen (Tables 1 and 2). The 24 h time point seems to be the most critical timepoint at which maximum differences in uptakes were observed among the tissues and organs for AAV9 and AAVBR1 (Tables 1 and 2) serotypes. Additional significant differences in uptakes were seen with [89Zr]Zr-AAV9-CMV-fLuc and [89Zr]Zr-AAVBR1-CMV-fLuc in the lungs, muscle, brain, and vertebra for up to 6 days post injection (Supplementary Information, Tables S2 & S3). Overall, higher uptake of [89Zr]Zr-AAVBR1-CMV-fLuc was observed in the lungs and brain only at day 6–12 after injection. At day 14 and day 18, the brain and gut were the only organs that showed significant differences in uptake of [89Zr]Zr-AAV9-CMV-fLuc and [89Zr]Zr-AAVBR1-CMV-fLuc (Supplementary Information, Tables S2 & S3).

The PET imaging data showed no gender-based differences in uptake of [89Zr]Zr-AAV9-CMV-fLuc in any of the organs and the same was true for [89Zr]Zr-AAVBR1-CMV-fLuc except for the kidney, as [89Zr]Zr-AAVBR1-CMV-fLuc showed higher kidney uptake in the females mice compared to the males mice after 24 h post-injection (p-value < 0.05).

Based on the ex vivo biodistribution analysis performed at day 18 post-injection, the majority of radioactivity was observed in the liver (SUV of 4.61 ± 0.62 for AAVBR1 and 3.59 ± 0.92 for AAV9), spleen (SUV 2.68 ± 0.75 for AAVBR1 and 2.26 ± 0.53 for AAV9), and kidneys (SUV 0.70 ± 0.16 for AAVBR1 and 0.41 ± 0.12 for AAV9) as presented in Fig. 7 and Supplementary Information, Table S3.

Significantly higher uptake of [89Zr]Zr-AAVBR1-CMV-fLuc was observed as compared to the [89Zr]Zr-AAV9-CMV-fLuc in the brain, lungs, kidneys, pancreas, adipose, cecum and bladder at day 18 post-injection as presented in Fig. 7 and Supplementary Information, Table S3.

Additional differences were observed in the ex vivo biodistribution analysis on comparing AAV uptake in male and female mice at day 18 post-injection (Supplementary Information, Table S4). The [89Zr]Zr-AAVBR1-CMV-fLuc showed significantly higher uptake in male mice muscle (p-value = 0.002), skin (p-value = 0.04) and salivary gland (p-value = 0.01) as compared to female mice. Whereas female mice showed higher [89Zr]Zr-AAVBR1-CMV-fLuc uptake in kidney than the male mice (p-value = 0.02) at day18 post-injection (Supplementary Information, Table S4). On the other hand, in the [89Zr]Zr-AAV9-CMV-fLuc showed higher uptakes in male mice muscle (p-value = 0.03), mesentery (p-value = 0.02) and spleen (p-value = 0.01) than female mice (Supplementary Information, Table S4).

Based on the ex vivo biodistribution data, within male mice, [89Zr]Zr-AAVBR1-CMV-fLuc showed significantly higher uptake in the pancreas, skin, brain, salivary gland, and cecum than [89Zr]Zr-AAV9-CMV-fLuc male mice cohort (p-value = 0.04, 0.003, 0.02, 0.01 and 0.04 respectively) (Supplementary Information, Table S4). Within female mice, [89Zr]Zr-AAVBR1-CMV-fLuc showed significantly higher uptake in the brain and kidney than [89Zr]Zr-AAV9-CMV-fLuc (p-value = 0.04 and 0.02, respectively) (Supplementary Information, Table S4). No difference in uptake of [89Zr]Zr-AAV9-CMV-fLuc and [89Zr]Zr-AAVBR1-CMV-fLuc were observed in mice male or female reproductive organs on ex vivo biodistribution (Supplementary Information, Table S4).

The [89Zr]Zr-AAVBR1-CMV-fLuc showed higher uptake (SUV) in the brain and lung as compared to [89Zr]Zr-AAV9-CMV-fLuc both via ex vivo biodistribution and PET image analysis. Although the trend observed in PET image analysis and ex vivo biodistribution are still valid, it was not surprising that the absolute SUV values in ex vivo biodistribution and PET imaging-derived data differed. Lodge et al. also observed this mismatch between PET and ex vivo data and showed that PET based uptake measurements tend to be higher than uptake measurements based on ex vivo biodistribution42.

To correlate the biodistribution of [89Zr]Zr-AAV9-CMV-fLuc and [89Zr]Zr-AAVBR1-CMV-fLuc with the infection profile, luciferase expressions were assessed (Figs. 8, 9 and 10). The cohort of animals injected with [89Zr]Zr-AAVBR1-CMV-fLuc showed higher luciferase expression in the brain and lungs as compared to [89Zr]Zr-AAV9-CMV-fLuc cohort. Whereas the cohort of animals injected with [89Zr]Zr-AAV9-CMV-fLuc showed higher luciferase expression in the liver and muscle than [89Zr]Zr-AAVBR1-CMV-fLuc cohort. As expected, the AAV2 variant, AAVBR1, has shown primary infection in the brain and lungs after intravenous administration; similar results were also obtained in previous preclinical studies10,11,12,13. The higher luciferase signal in the brain was observed in the [89Zr]Zr-AAVBR1-CMV-fLuc injected cohort than in the [89Zr]Zr-AAV9-CMV-fLuc cohort, which matched with PET imaging and ex vivo biodistribution results (Tables 1 and 2; Figs. 7, 8, 9 and 10) at all time points after 5 min post-injection. In the case of the lungs, a higher uptake of [89Zr]Zr-AAVBR1-CMV-fLuc was observed at 24 h time point, as assessed by PET imaging, and also at day 18, as assessed by the ex vivo biodistribution. These two observations correlated well with the higher lung luciferase signals for the [89Zr]Zr-AAVBR1-CMV-fLuc injected cohort (Tables 1 and 2; Figs. 7, 8, 9 and 10 and Supplementary Information, Table S3).

Luminescence measurements expressed as relative light units (RLU) in dissected organs from BALB/c mice in the third week after systemic injection of [89Zr]Zr-AAV9-CMV-fLuc (n = 4) or [89Zr]Zr-AAVBR1-CMV-fLuc (n = 4) showing A high luciferase expression organs and B lower luciferase expression organs.

In the case of the muscle, although higher uptake of [89Zr]Zr-AAVBR1-CMV-fLuc was observed at different time points until day 7 post-injection, the luciferase expression showed higher signals in the muscle for animals injected with [89Zr]Zr-AAV9-CMV-fLuc as compared to animals injected with [89Zr]Zr-AAVBR1-CMV-fLuc (Figs. 8, 9 and 10 and Supplementary Information, Table S3). This disconnect between the uptake of AAVs and luciferase signal in the muscle could be due to the differences in the transduction efficiency between AAV9 and AAVBR1 in the muscles13,43,44. It has been reported that the transduction efficiency of AAV9 is more effective in the muscle than any other serotypes including AAV2/AAVBR1 upon local delivery in the muscle43. Additionally, it is possible that the higher transduction efficiency of [89Zr]Zr-AAV9-CMV-fLuc in muscles led to a higher luciferase expression in the muscle of mice injected with the [89Zr]Zr-AAV9-CMV-fLuc, despite of lower uptake of the [89Zr]Zr-AAV9-CMV-fLuc in the muscle as compared to [89Zr]Zr-AAVBR1-CMV-fLuc as seen by PET imaging.

At early time points, the PET signal is expected to be primarily from the radiolabeled AAVs administered in the body, but with time, as the AAVs infect different tissues, the PET signal could be a combination of functional virus, empty capsids or degraded virus product due to virus disassembly following successful infection. After disassembly, the body can clear the radiolabeled capsid protein through the liver, kidney, spleen, or gut. Nevertheless, it was encouraging to observe that PET imaging showed an expected higher uptake of [89Zr]Zr-AAVBR1-CMV-fLuc as compared to [89Zr]Zr-AAV9-CMV-fLuc in the brain in BALB/c mice as early as 15 min post-injection and the difference in the uptake in these organs stayed as late as day 18 post-injection. This suggests that longitudinal PET imaging of 89Zr-labeled AAVs could help understand the tissue tropism of different serotypes at multiple days post-administration.

The present study emphasizes the importance of PET imaging in delineating the impact of viral tropism and transduction efficiency in gene therapy. PET imaging can be used as a noninvasive tool to monitor organ or tissue-specific design and development of novel AAV serotypes and their modifications. Therefore, a serotype with a desired tropism to a particular organ or tissue can be selected, validated, and efficiently advanced to human translation using PET-based AAV imaging.

Conclusions

In this study, a direct virus radiolabeling method using [89Zr]Zr-DBN has been developed and two AAV serotypes, AAV9 and AAVBR1, were successfully radiolabeled and evaluated for their biodistribution over time in normal BALB/c mice. Their structural integrity and transduction properties were measured to ensure no negative effect is displayed on their nature of function after radiolabeling. Noninvasive PET imaging of AAVs showed differences in trafficking of AAVBR1 and AAV9 in mice. The [89Zr]Zr-AAVBR1-CMV-fLuc showed a significantly higher uptake in the brain as compared to [89Zr]Zr-AAV9-CMV-fLuc. Overall, the developed direct virus radiolabeling methodology can be used as a tool for image guided design and development of novel gene therapies.

Methods

General consideration

89Y foil (0.1 mm, 50 × 50 mm 99.6% REO; Thermo Scientific chemicals), PETtrace cyclotron (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI). Trace metal grade sodium carbonate and oxalic acid were purchased from Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, and trace metal grade solvents such as nitric acid (67–70%) and hydrochloric acid (34–37%) were obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA. 0.9% saline was purchased from Hospira Inc., Lake Forest, IL. The iTLC-Silica gel was acquired from Agilent technologies, Santa Clara, CA. The labeling chelator p-SCN-Bn-Deferoxamine (B-705, ≥ 94%) was purchased from Macrocyclics, Plano, TX. The viruses were obtained from SignaGen. The empty Luer-Inlet SPE cartridges (1 mL) with frits (20 μm pore size) were obtained from Supelco Inc., Bellefonte, PA and Chromafix®. 30-PS-HCO3 PP cartridges were obtained from Macherey-Nagel (Duren, Germany) and 0.22 μm Millex-GV® filter from Millipore Sigma, St. Louis, MO. Two different serotypes of AAV, AAV9-CMV-fLuc (2.66 × 1013 VG/mL) and AAV2 variant, AAVBR1-CMV-fLuc (1.16 × 1013 VG/mL) were obtained from SignaGen Laboratories, Frederick, MD in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) at pH 7.5. Laemmli sample buffer was obtained from Bio-Rad laboratories, Hercules, CA) and 1X NuPAGE sample reducing agent was obtained from Life Technologies Corporation, Carlsbad CA. Sephadex G50 resin was purchased from Cytiva LifeSciences Marlborough, MA and Econo-Pac® Chromatography Columns were from Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA to prepare Sephadex G50 columns. For preparation of column, the Sephadex G50 resin was first allowed to swell by incubating 2 g resin in 40 mL phosphate buffered saline at pH 7.2 for ~ 16 h at 4 °C. After swelling of the resin, the Econo-Pac® Chromatography Columns were packed with the resin at a bed volume of ~ 15.0 mL with frit at the top and bottom of the resin. Mini-PROTEAN TGX Gel was purchased from Bio-Rad laboratories, Hercules, CA. Precision Plus Protein All Blue Standards (10–250 kDa) were purchased from Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). ProteoSilver Plus Silver Stain Kit was purchased from Sigma, St. Louis, MO.

Production and purification of Zr-89

The 89Zr was produced using a PETtrace cyclotron (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI) through the 89Y(p, n)89Zr reaction using two 0.1 mm 89Y target foils ( 99.9%, Alfa-Aesar, Haverhill, MA), as described previously by Pandey et al.39. Briefly, an incident proton beam energy of ~ 15.2 MeV was applied using a 0.1 mm Al degrader foil at 40 µA beam current on yttrium foils of overall thickness of 0.2 mm for 3 h irradiation to yield 130.13 ± 18.66 mCi (4.81 ± 0.69 GBq, n = 10) of 89Zr, decay corrected to the end of bombardment. 89Zr was purified as [89Zr]Zr-oxalate using in-house produced hydroxamate resin45,46,47,48 and then converted into [89Zr]Zr-chloride using Chromafix® 30-PS-HCO3 PP cartridges (45 mg)49. The final elution of [89Zr]Zr-chloride was performed using 1 N HCl (0.5 mL) in a V-vial followed by drying under a steady flow of nitrogen gas at 65–70 °C for 10–30 min.

Radiosynthesis of [89Zr]Zr-DBN

The purified and dried form of [89Zr]ZrCl4 (240.5–377.4 MBq or 6.5–10.2 mCi) was resuspended in Milli Q -water (17–50 µL) and vortexed for 2 min to homogenize. Approximately 78.44–325.97 MBq (2.12–8.81 mCi) of [89Zr]ZrCl4 was transferred in a clean low protein-binding Eppendorf tube, followed by the addition of 0.5 M Na2CO3 (5–22 µL, depending on amount of starting [89Zr]ZrCl4 ) to get a desired pH of 7.5. Thereafter, 2.00–2.25 µg of DFO-NCS (1.0-1.25 µL of 2.5 mM DFO-NCS; DMSO) was added and the resultant reaction mixture was incubated at room temperature for 30 min. The chelation efficiency was evaluated using radio-thin layer chromatography (radio-iTLC) in 100 mM DTPA (pH 7.0) solution and analyzed on a radio-iTLC scanner (Eckert & Ziegler, Valencia, CA). The [89Zr]Zr-DBN showed Rf = 0-0.176, and [89Zr]ZrCL4 showed Rf = ~ 0.83-1.0 on radio-iTLC. The final chelation efficiency was calculated using the below mathematical formula.

Virus radiolabeling with [89Zr]Zr-DBN

To 200 µL of AAV stock (5.32 × 1012 AAV9-CMV-fLuc or 2.32 × 1012 AAVBR1-CMV-fLuc) in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) at pH 7.5, 6.5–10 µL of Na2CO3 (0.1 M) was added to obtain a pH of 9.0. After adjusting the pH, 15–35 µL of [89Zr]Zr-DBN solution (pH 7.5) was added. The volume of the final reaction mixture ranged from 224 to 245 µL, and pH remained at 9.0 after the addition of [89Zr]Zr-DBN solution. To allow radiolabeling of AAVs, the resulting reaction mixture was incubated for 30 min at 37 °C. The radiochemical yield (RCY) was calculated using r-TLC with 30 mM sodium citrate (pH 5.0) and methanol (1:1) as the mobile phase. In the r-iTLC, the [89Zr]Zr-AAVs showed Rf = 0.017–0.08, and [89Zr]Zr-DBN showed Rf = 0.716–0.801. The final RCY was calculated using the following mathematical formula.

The radiolabeled viruses were purified using a size exclusion column with a 15.0 mL bed volume in phosphate-buffered saline. The column was prepared using Sephadex G50 resin in Econo-Pac® Chromatography Columns using swelled Sephadex 50 resin as mentioned in the general consideration section. The radiochemical purity of the radiolabeled viral preparation was assessed by r-TLC using 30 mM sodium citrate (pH 5.0) and methanol (1:1) as the mobile phase.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and Autoradiography

The SDS-PAGE was performed as per the established protocol50. Both unlabeled AAVs and radiolabeled AAVs were diluted with 2X Laemmli sample buffer and 1X NuPAGE sample reducing agent (1:1, v: v). The diluted protein samples were reduced at 80 °C for 3 min. The reduced proteins were resolved by one-dimensional SDS-PAGE in 10.0% Mini-PROTEAN TGX Gel in 1× Tris-Glycine-SDS running buffer. Precision plus protein all blue standards (10–250 kDa) were used as the protein marker. After electrophoresis, autoradiography was performed for detecting [89Zr]Zr-DBN-capsid protein in the gel using a Cyclone Plus Storage Phosphor System (PerkinElmer Corporation, Waltham, MA). The autoradiograph was visualized using Image J software51. Following autoradiography, gels were silver stained using the ProteoSilver Plus Silver Stain Kit.

Estimation of DFO molecule conjugated per viral particle

For calculation of DFO molecules conjugated to viral particle or capsid protein subunits, we applied purity and molar activity of [89Zr]Zr-DBN in association with number of viral particles used in conjugation to come up with the number of DFO molecules conjugated with viral particles. Since we used > 98% pure [89Zr]Zr-DBN for radiolabeling of AAV9-CMV-fLuc and AAVBR1-CMV-fLuc, the amount of radioactivity associated with radiolabeled viral preparation can be used as a readout to calculate amount of DFO conjugated to the virus particles.

In the case of AAV9-CMV-fLuc, 5.32 × 1012 viral particles, were incubated with 0.098 GBq (2.66 mCi) of [89Zr]Zr-DBN having molar activity of 37.05 GBq/µmol (1.00 Ci/µmol) with > 98% radiochemical purity. Post-radiolabeling and after size exclusion purification, 0.017 GBq (0.47 mCi) radioactivity was recovered in purified virus fractions. In terms of radioactivity this comes out to be 17.67% recovery (Supplementary Information, Table S1). Based on the applied methodology, out of 2656.39 pmol of DFO incubated with AAV9-CMV-fLuc, 469.36 pmol (17.67% of 2656.39 pmol) was recovered in the fractions with radiolabeled AAV9-CMV-fLuc. According to Avogadro’s law, one mole of DFO can be assumed to have 6.022 × 10²³ DFO molecules40. This means that 469.36 pmol would contain 2.83 × 1014 DFO molecules. The total number of virus particles recovered in the purified fractions were 2.93 × 1012. Simply dividing number of DFO molecules with recovered viral particles, we found, 96.59 DFO molecule were conjugated per AAV9-CMV-fLuc particle. Similar calculation was performed for radiolabeled AAVBR1-CMV-fLuc and it yielded 66.45 DFO molecules per AAVBR1-CMV-fLuc particle. Furthermore, DFO molecules are conjugated to the capsid proteins of the AAV particle and each AAV particle is composed of 60 viral protein subunits in a capsid in a particular ratio of 1:1:10 (VP1:VP2: VP3). Applying the radioactive SDS PAGE (autoradiography), the distribution of radioactivity among the viral protein subunits (VP1, VP2 and VP3) was visualized and quantified using Image J software51. The number of DFO molecules conjugated to each capsid protein subunit were calculated and summarized in the Fig. 3.

Animals

BALB/c mice were used and obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME USA). At the time of injection, animals in every group had a 1:1 male to female ratio, they all were 10–11 weeks old, and their body weights were 30.5 ± 2.64 g (n = 8) for males and 23.4 ± 2.1 g (n = 8) for females.

PET imaging and ex vivo biodistribution studies

Radiolabeled AAVs, AAV9-CMV-fLuc (~ 2 × 1011 VP; 29.15 ± 1.04 µCi (n = 8)) and AAVBR1-CMV-fLuc (~ 0.8 × 1011 VP; 19.79 ± 0.9 µCi (n = 8)), were administered via tail vein injection in separate groups of mice. All the animals were anesthetized for tail vein injection and PET imaging using an induction dose of 2–3% isoflurane and a maintenance dose of 1–2% isoflurane, which was administered via an isoflurane vaporizer. All anesthetized animals were kept warm during imaging using a heat supported imaging chamber. For PET imaging studies, each animal underwent a 15 min dynamic PET scan (Framing Sequence: 1 × 10, 4 × 15, 8 × 30, 10 × 60) immediately after injection of radiolabeled AAVs followed by 10 min static images at 2 h, 4 h, 24 h, 48 h, day 3, day 4, day 6, day 7, day 12, day 14 and day 18 post-injection. The PET scans were performed on a small animal micro-PET/X-ray system, Genesys 4 (Sofie BioSystems, Dulles, VA, USA). The obtained PET images were overlayed and aligned by mouse X-ray atlas, and then the SUV threshold on the PET images was increased to delineate the organ and region of interest. Additionally, the ROIs in an organ or in a tissue were manually drawn across various planes of the PET image using the ellipsoid ROI tool in the image analysis AMIDE software (Supplementary Information, Fig. S7) and compared among various groups of animals at different timepoints using same SUV threshold. Extra care has been taken to avoid any overlapping regions.

The anatomic reference skeleton images overlayed on PET images are X-ray images. These X-ray atlas images are just for reference. They were constructed by the Genesys 4 software using the mouse atlas registration system algorithm with information obtained from the stationary top-view planar X-ray projector and side-view optical camera of the small animal Genesys4 PET/X-ray system (Sofie BioSystems, Dulles, VA, USA).

The PET images were reconstructed using the Genesys 4 imaging software installed on the imaging system. The reconstructed PET images were visualized in the sagittal planes, and scaled to the SUV using image analysis software, MIM 7.2.7 software (MIM Software Inc., Cleveland, OH, USA) showing uptake of radiolabeled AAVs in different organs, where;

After the last PET/X-Ray or luciferase imaging (as shown below) session, the chest of the anesthetized animal was opened with a midline incision and sternum was resected. Following this, the heart was excised (cardiectomy) for euthanasia. After euthanasia, the organs/tissues were collected and counted for radioactivity using a gamma counter for ex vivo biodistribution of AAVs as standardized uptake value (SUV) in different organs or luciferase signals. SUV was calculated using the SUV formula shown above.

AAV9 or AAVBR1 quantification

The AAV9-CMV-fLuc or AAVBR1-CMV-fLuc in purified fractions were quantified by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR)52 using fLuc specific primers (forward: 5’-CGGAAAGACGATGACGGAAA-3’ and reverse: 5’-CGGTACTTCGTCCACAAACA-3’) that generated a 103-bp fragment of fLuc region. The qPCR was performed in iTaq Universal SYBR Green Supermix Assay (Bio-Rad laboratories, Hercules, CA) in CFX-Connect Real Time Systems thermocycler (Bio-Rad laboratories, Hercules, CA). For qPCR quantification, a standard curve was made using a range of different amount of AAV9-CMV-fLuc (2.66 × 1012 – 1.77 × 1010) or AAVBR1-CMV-Fluc (1.16 × 1012 – 7.73 × 109 VP) in the qPCR plotted against their respective threshold cycle (Cq) value in a qPCR reaction. Each ~ 20 µL qPCR assay contained 4 µL AAV preparation. For unknown samples, the amount of AAV in each qPCR assay was estimated using the Cq value of unknowns plotted against the above-mentioned standard curve. Each ~ 20 µL qPCR assay contained 4 µL radiolabeled AAV preparation from each fraction after size exclusion purification. An appropriate dilution factor was applied to finally estimate the total number of AAVs in each fraction.

Luciferase imaging

For assessment of organs/tissues that were transfected with intravenously administered AAVs. Each animal was injected with 150 mg luciferin/kg body weight via intraperitoneal injection in the third week or > 30 days post-injection of radiolabeled AAVs. After 15 min of injection, the anesthetized animal was laid down in prone or supine position on the imaging bed in Xenogen IVIS-200 System (Perkin Elmer, Waltham MA). The imaging bed was pre-warmed at 37 °C with the animal under continuous 1–2% isoflurane inhalation. The photographs and luminescent images of mouse or dissected organs were acquired with the exposure time at auto setting and overlayed using imaging acquisition and processing software, Living Image 4.5.2. (Perkin Elmer, Waltham MA).

Statistics

The obtained PET imaging and ex vivo biodistribution data were analyzed using Microsoft Excel program. Uptake values were compared using unpaired Student’s t-test analysis. Differences in uptake values were considered statistically significant when p value < 0.05. GraphPad Prism version 10.0.3 for Windows (GraphPad Software, Boston MA) was used for preparing graphs.

Data availability

All data generated in this study are presented in the current manuscript and in its supplementary information files.

References

Gonçalves, M. A. Adeno-associated virus: from defective virus to effective vector. Virol. J. 2, 43 (2005).

Li, C. & Samulski, R. J. Engineering adeno-associated virus vectors for gene therapy. Nat. Rev. Genet. 21, 255–272 (2020).

Deyle, D. R. & Russell, D. W. Adeno-associated virus vector integration. Curr. Opin. Mol. Ther. 11, 442–447 (2009).

Kuzmin, D. A. et al. The clinical landscape for AAV gene therapies. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 20, 173–174 (2021).

Manfredsson, F. P., Rising, A. C. & Mandel, R. J. AAV9: a potential blood-brain barrier buster. Mol. Ther. 17, 403–405 (2009).

Chan, K. Y. et al. Engineered AAVs for efficient noninvasive gene delivery to the central and peripheral nervous systems. Nat. Neurosci. 20, 1172–1179 (2017).

Chatterjee, D. et al. Enhanced CNS transduction from AAV.PHP.eB infusion into the cisterna magna of older adult rats compared to AAV9. Gene Ther. 29, 390–397 (2022).

Tanguy, Y. et al. Systemic AAVrh10 provides higher transgene expression than AAV9 in the brain and the spinal cord of neonatal mice. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 8, 36 (2015).

Hoshino, Y. et al. The adeno-associated virus rh10 vector is an effective gene transfer system for chronic spinal cord injury. Sci. Rep. 9, 9844 (2019).

Kawabata, H., Konno, A., Matsuzaki, Y. & Hirai, H. A blood-brain barrier-penetrating AAV2 mutant created by a brain microvasculature endothelial cell-targeted AAV2 variant. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 29, 81–92 (2023).

Merkel, S. F. et al. Trafficking of adeno-associated virus vectors across a model of the blood-brain barrier; a comparative study of transcytosis and transduction using primary human brain endothelial cells. J. Neurochem. 140, 216–230 (2017).

Dogbevia, G., Grasshoff, H., Othman, A., Penno, A. & Schwaninger, M. Brain endothelial specific gene therapy improves experimental sandhoff disease. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 40, 1338–1350 (2020).

Körbelin, J. et al. A brain microvasculature endothelial cell-specific viral vector with the potential to treat neurovascular and neurological diseases. EMBO Mol. Med. 8, 609–625 (2016).

Verdera, H. C., Kuranda, K. & Mingozzi, F. AAV Vector Immunogenicity in humans: a long journey to successful gene transfer. Mol. Ther. 28, 723–746 (2020).

Wang, S. K., Lapan, S. W., Hong, C. M., Krause, T. B. & Cepko, C. L. In situ detection of Adeno-associated viral Vector genomes with SABER-FISH. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 19, 376–386 (2020).

Liu, S. L. et al. Single-virus Tracking: from imaging methodologies to virological applications. Chem. Rev. 120, 1936–1979 (2020).

Concilio, S. C., Russell, S. J. & Peng, K. W. A brief review of reporter gene imaging in oncolytic virotherapy and gene therapy. Mol. Ther. Oncolytics. 21, 98–109 (2021).

Meier, S. et al. Non-invasive detection of adeno-associated viral gene transfer using a genetically encoded CEST-MRI reporter gene in the murine heart. Sci. Rep. 8, 4638 (2018).

Li, M., Wang, Y., Liu, M. & Lan, X. Multimodality reporter gene imaging: construction strategies and application. Theranostics 8, 2954–2973 (2018).

Lux, K. et al. Green fluorescent protein-tagged Adeno-Associated Virus particles allow the study of cytosolic and nuclear trafficking. J. Virol. 79, 11776–11787 (2005).

Kelich, J. M. et al. Super-resolution imaging of nuclear import of adeno-associated virus in live cells. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2, 15047 (2015).

Joo, K. I. et al. Enhanced real-time monitoring of adeno-associated virus trafficking by virus-quantum dot conjugates. ACS Nano. 5, 3523–3535 (2011).

Kothari, P. et al. Radioiodinated Capsids facilitate in vivo Non-invasive Tracking of Adeno-Associated Gene transfer vectors. Sci. Rep. 7, 39594 (2017).

Seo, J. W. et al. Positron emission tomography imaging of novel AAV capsids maps rapid brain accumulation. Nat. Commun. 11, 2102 (2020).

Yoon, S. et al. Recent advances in optical imaging through deep tissue: imaging probes and techniques. Biomater. Res. 26, 57 (2022).

Park, G. K., Hoseok, S., Kim, G. S., Hwang, N. S. & Choi, H. S. Optical spectroscopic imaging for cell therapy and tissue engineering. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev. 53, 360–375 (2018).

Castelletto, S. & Boretti, A. Viral particle imaging by super-resolution fluorescence microscopy. Chem. Phys. Impact. 2, 100013 (2021).

Wang, J. et al. Multi-color super-resolution imaging to study human coronavirus RNA during cellular infection. Cell. Rep. Methods. 2, 100170 (2022).

Räty, J. K. et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of viral particle biodistribution in vivo. Gene Ther. 13, 1440–1446 (2006).

Salegio, E. A., Bringas, J. & Bankiewicz, K. S. MRI-Guided delivery of viral vectors. Methods Mol. Biol. 1382, 217–230 (2016).

Volpe, A., Pillarsetty, N. V. K., Lewis, J. S. & Ponomarev, V. Applications of nuclear-based imaging in gene and cell therapy: probe considerations. Mol. Ther. Oncolytics. 20, 447–458 (2021).

Griffeth, L. K. Use of PET/CT scanning in cancer patients: technical and practical considerations. Proc. (Bayl Univ. Med. Cent). 18, 321–330 (2005).

Jiang, D. & Hong, H. Mapping COVID-19 with nuclear imaging: from infection to functional sequelae. Am. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging. 11, 59–63 (2021).

Davison, J. M. et al. FDG PET/CT in patients with HIV. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 197, 284–294 (2011).

Huang, Q. et al. Delivering genes across the blood-brain barrier: LY6A, a novel cellular receptor for AAV-PHP.B capsids. PLoS One. 14, e0225206 (2019).

Hordeaux, J. et al. The GPI-Linked protein LY6A drives AAV-PHP.B transport across the blood-brain barrier. Mol. Ther. 27, 912–921 (2019).

Yoon, J. K., Park, B. N., Ryu, E. K., An, Y. S. & Lee, S. J. Current perspectives on 89Zr-PET imaging. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 4309 (2020).

Bansal, A. et al. Novel 89Zr cell labeling approach for PET-based cell trafficking studies. EJNMMI Res. 5, 19 (2015).

Pandey, M. K. et al. A new solid target design for the production of 89Zr and radiosynthesis of high molar activity [89Zr]Zr-DBN. Am. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging. 12, 15–24 (2022).

International Committee for Weights and Measures. Proceedings of the 106th meeting (16–17 and 20 October 2017) (2017). www.bipm.org/utils/en/pdf/CIPM/CIPM2017-EN.pdf).

Kotchey, N. M. et al. A potential role of distinctively delayed blood clearance of recombinant adeno-associated virus serotype 9 in robust cardiac transduction. Mol. Ther. 19, 1079–1089 (2011).

Lodge, M. A. et al. Measurement of PET quantitative Bias in vivo. J. Nucl. Med. 62, 732–737 (2021).

Rasmussen, C. L. M. et al. A novel strategy for delivering Niemann-pick type C2 proteins across the blood-brain barrier using the brain endothelial-specific AAV-BR1 virus. J. Neurochem. 164, 6–28 (2023).

Muraine, L. et al. Transduction efficiency of adeno-associated virus serotypes after local injection in mouse and human skeletal muscle. Hum. Gene Ther. 31, 233–240 (2020).

Pandey, M. K. et al. Improved production and processing of 89Zr using a solution target. Nucl. Med. Biol. 43, 97–100 (2016).

Pandey, M. K., Engelbrecht, H. P., Byrne, J. P., Packard, A. B. & DeGrado, T. R. Production of 89Zr via the 89Y(p,n)89Zr reaction in aqueous solution: effect of solution composition on in-target chemistry. Nucl. Med. Biol. 41, 309–316 (2014).

Pandey, M. K. & DeGrado, T. R. Cyclotron production of PET radiometals in liquid targets: aspects and prospects. Curr. Radiopharm. 14, 325–339 (2021).

Sharma, S. & Pandey, M. K. Radiometals in imaging and therapy: highlighting two decades of research. Pharmaceuticals 16, 1460 (2023).

Larenkov, A. et al. Preparation of Zirconium-89 solutions for radiopharmaceutical purposes: interrelation between formulation, radiochemical purity, stability and biodistribution. Molecules 24, 1534 (2019).

Schägger, H. & von Jagow, G. Tricine-sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for the separation of proteins inthe range from 1 to 100 kDa. Anal. Biochem. 166, 368–379 (1987).

Schneider, C. A., Rasband, W. S. & Eliceiri, K. W. NIH image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods. 9, 671–675 (2012).

Sommer, J. M. et al. Quantification of adeno-associated virus particles and empty capsids by optical density measurement. Mol. Ther. 7, 122–128 (2003).

Acknowledgements

This study was financially supported by the Department of Radiology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.B.: Performed radiolabeling, imaging studies, data analysis and contributed to manuscript writing. S.S.: Performed 89Zr purification, imaging studies, data analysis and contributed to manuscript writing. M.K.: Performed imaging studies, data analysis and contributed to manuscript writing. M.K.P.: Conceptualized, designed, and guided the study, and edited the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript before submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

A.B. and M.K.P. are the inventors of the [89Zr]Zr-DBN based cell labeling technology [US20180043041A1]. Rest of the authors do not have any competing interest.

Ethical standards

All the animal studies, methods and experimental protocols used in this study were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. All the animal studies, methods and experimental protocols were approval by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA, which is a part of the Public Health Service (PHS) Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the Office of the Laboratory Animal Welfare (OLAW) of the United States. The IACUC guidelines and regulations for animal handling and care in this study are equivalent to the ARRIVE guidelines, hence this study was performed in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bansal, A., Sharma, S., Kethamreddy, M. et al. PET imaging of AAV9 and AAVBR1 trafficking in normal mice. Sci Rep 15, 4257 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86815-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86815-0