Abstract

This study employed large eddy simulation (LES) with the wall-adapting local eddy-viscosity (WALE) model to investigate transitional flow characteristics in an idealized model of a healthy thoracic aorta. The OpenFOAM solver pimpleFoam was used to simulate blood flow as an incompressible Newtonian fluid, with the aortic walls treated as rigid boundaries. Simulations were conducted for 30 cardiac cycles and ensemble averaging was employed to ensure statistically reliable results. Main hemodynamic parameters, such as velocity fields, turbulence intensity turbulent kinetic energy (TKE), oscillatory shear index (OSI) and wall shear stress (WSS), were analyzed throughout the circulatory system. Through 3D computational fluid dynamics (CFD) visualization, we explained the transition from laminar to turbulent flow and its development throughout the cardiac cycle. The results demonstrated that turbulence originates in the aortic arch following the peak systole phase and further develops in the aortic arch and descending aorta during the mid-deceleration and end-systole phases, with the maximum turbulence intensity exceeding 25%. WSS reached up to 30 Pa during the peak systole, with an average WSS of 6.5 Pa across the cardiac cycle. Low and oscillatory WSS were observed during diastole which can potentially contribute to the development of vascular diseases including, aortic dissection and atherosclerosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The aorta is the largest artery in the human body, characterized by extensive curvature. The ascending aorta originates from the left ventricle of the heart and extends down to the abdomen. The aortic arch consists of three main branches: the brachiocephalic artery (BCA), the left common carotid artery (LCCA), and the left subclavian artery (LSA). The descending thoracic aorta travels downward through the thoracic vertebrae1,2. Aorta serving as the main cardiac output is continuously exposed to high pulsatile pressure and shear stress, making it susceptible to biomechanical damage3. The complex velocity fluctuation in the aortic arch and descending thoracic aorta with a high Reynolds number can lead to a transition to turbulent flow4,5,6.

Numerous in vivo studies have demonstrated that turbulence can develop in the healthy normal aorta. Ha et al.7 used four-dimensional flow magnetic resonance imaging (4D Flow MRI) to quantify turbulent kinetic energy (TKE), a metric of turbulence intensity, in the aortas of two groups: young healthy individuals and older healthy individuals. Their study revealed that turbulent flow was present in the aortas of all subjects. Stein et al.8 employed a hot film anemometer probe to measure point velocities in the ascending aorta of seven individuals with normal aortic valves and those with aortic valvular disease, confirming turbulent flow in both groups. Sundin et al.9,10 suggested that while blood flow in the normal cardiovascular system is predominantly laminar, it operates close to the turbulence threshold. They also noted that high stress and elevated cardiac output can increase turbulence intensity in the healthy thoracic aorta. Arzani et al.11 compared numerical predictions of turbulence intensity with in vivo measurements using time-resolved three-directional phase-contrast (PC) MRI data, demonstrating good agreement between MRI measurements and CFD-predictions of turbulence intensity. Pietrasanta et al.12 investigated the turbulent flow downstream of a transcatheter aortic valve (TAV) using in vitro measurements in a validated pulse replicator with a (Tomographic Particle Image Velocimetry) Tomo-PIV system and discussed the effect of different implantation positions on the structure and intensity of turbulence.

With significant advancements in numerical techniques and computing power, computational fluid dynamics (CFD) has become an important tool for understanding complex blood flow fields. Shahcheraghi et al.13 established the idealized symmetrical aorta model and computed the detailed flow field based on laminar flow assumption. They observed that velocity profiles were skewed towards the inner wall, with the extensive secondary flow motion in the aorta influenced by the presence of branches. Benim et al.14 assumed Newtonian fluid and rigid wall conditions to simulate the human aorta, focusing on the aortic arch and its major branches under steady-state and pulsatile flow conditions using \(\:k-\omega\:\:\)SST turbulent model. Lantz et al.6 applied in vivo flowrate waveform measured by MRI as the inlet boundary condition to quantify the human specific aortic flow with large eddy simulation (LES) and described the effects of turbulent fluctuations on wall shear stress (WSS). Casacuberta et al.15 performed aortic simulation by using the OpenFOAM, and compared it with Ansys Fluent, while Zakaria et al.16 investigated blood flow in the elderly man’s aorta using OpenFOAM with the LES k-equation eddy viscosity model and provided detailed visual results. In recent study, Becsek et al.17 performed computational simulations of the flow past a bioprosthetic aortic valve to investigate the effect of turbulence on WSS and turbulent dissipation rates. Their finding revealed that turbulent flow led to elevated shear stress levels along the wall of the ascending aorta with a strong fluctuating and chaotic wall shear stress patterns. Buchner et al.18 analyzed kinetic energy distribution in both healthy aortas and those with aortic valve stenosis (AVS), their findings revealed that turbulence is more pronounced in the ascending aorta, with complex flow structures contributing to increased turbulence intensity. Their findings also indicated that aortic valve stenosis alters wall shear stress patterns, correlating higher turbulence with elevated wall shear stress in the ascending aorta. Similarly, Manchester et al.19 utilized 4D flow MRI for four aortic geometries in patients with aortic valve disease. Their pulsatile LES revealed turbulence in all aortas, with the highest levels occurring during systolic deceleration. Khalid et al.20 employed high-resolution large-eddy simulations (HRLES) to simulate pulsatile blood flow in artery model, discovering that turbulence in non-Newtonian flow regimes deviates from traditional Kolmogorov turbulence. Qiao et al.21applied a fluid-structure interaction (FSI) framework to predict aortic temperature distribution. They also proposed a method to quantify energy loss from aortic wall deformation22.

While Reynolds-averaged Navier-Stokes (RANS) and large eddy simulation (LES) methods have been extensively employed in previous studies to investigate turbulent flow in diseased aortas, including conditions such as aortic stenosis, aneurysms, and coarctation23, the presence and characteristics of turbulence in healthy aortas remain insufficiently explored. Although some in vivo studies have reported turbulence in healthy aortas10,24, the characteristics of transition to turbulence has not been sufficiently addressed through computational fluid dynamics (CFD) methods. In addition, while subject-specific models provide crucial insights into individual hemodynamic patterns, their applicability can be limited due to anatomical variations across subjects. In contrast, an idealized model offers broader applicability and serves as a baseline reference for understanding turbulence in healthy aortas. This, in turn, can inform future subject-specific studies and clinical applications by providing foundational knowledge of how turbulence emerges and evolves under normal conditions. Furthermore, idealized models are computationally more efficient, allowing for a detailed statistical analysis of turbulent structures across multiple cardiac cycles. This, combined with our detailed analysis of turbulence characteristics significantly enhances our understanding of turbulence dynamics in aortic hemodynamics. Given these advantages, the present work utilizes LES for CFD analysis to elucidate the onset of turbulence and turbulent flow dynamics in a healthy aorta. In this context, the LES wall-adapting local eddy-viscosity (WALE) model is employed to investigate the development and extent of turbulence in an idealized thoracic aortic model under pulsatile flow conditions. This study reveals the detailed turbulence dynamics in the aorta during the laminar-to-turbulent transition. Based on 3D model visualization, this study provides multi-scale and multi-view visualization images that accurately show turbulence development and its extent. By analyzing multiple cardiac cycles, we provide insights into flow dynamics, turbulent features, flow patterns, and hemodynamic wall parameters such as WSS variations across different phases of the cardiac cycle, contributing significantly to cardiovascular research.

Numerical method

3D geometric model and computational mesh

The aorta model was constructed based on the geometry of Shahcheraghi et al.13 and Vasava et al.25 using SolidWorks as shown in Fig. 1. The geometric model is characterized by the extensive curvature for the ascending aorta and small torsional curvature in the descending thoracic aorta. In addition, three major branches such as the BCA, LCCA, and LSA are included. The diameter of the ascending aorta is 25 mm. The diameters of the BCA, LCCA, and LSA are 8.8 mm, 8.5 mm, and 9.9 mm, respectively.

The computational domain was discretized into a free tetrahedral mesh, using ICEM-CFD. A coarse mesh was initially employed to validate the setup and identify areas requiring refinement. The mesh was progressively refined based on initial simulation results with the regions exhibiting high-velocity gradients. Near-wall refinement included 10 prism layers to accurately capture boundary layer effects and turbulence dynamics. Solver settings were adjusted to ensure stability and accuracy, with criteria including Y + below 0.5, maximum non-orthogonality below 60° (average 8°), maximum skewness of 0.6, and maximum aspect ratio of 8. High aspect ratio cells, typically observed in fine boundary layers, may reduce convergence speed without critically compromising solver stability. A grid independence test was conducted using three different mesh sizes: Mesh 1: ~9 million elements; Mesh 2: ~14 million elements; and Mesh 3: ~20 million elements. A 20-second simulation test was performed using the maximum flow rate of the peak systole as the inlet condition, and the results were averaged for comparison. The velocity vectors were compared for each mesh configuration, as shown in Fig. 2. The results indicated no significant difference between Mesh 2 and Mesh 3. Therefore, a mesh with 14 million elements (Mesh 2) was used for the simulation results presented in this study.

Boundary conditions

In this study, blood was modeled as an incompressible Newtonian fluid in the aorta, with a constant viscosity of 0.0035 Pa·s and a density of 1050 kg/m3. The no-slip condition was applied to the rigid wall. The uniform velocity profile based on the pulsatile flowrate waveform, as shown in Fig. 3was applied at the entrance of aorta. In healthy aortic conditions, previous studies have indicated that the velocity profile generally exhibits symmetry26. In such cases, a one-dimensional axial velocity profile or uniform (flat) profile is often sufficient, particularly for the descending aorta26,27. Womersley or parabolic inlet velocity profiles, commonly employed in CFD studies of other anatomical regions like carotid and peripheral arteries, represent fully developed flow in a conduit with a long, constant diameter. However, since the ascending aorta is directly connected to the left ventricle, it may lack sufficient length for flow to fully develop, suggesting that a uniform velocity profile could provide a more realistic representation in this specific context. For the flow division to the three major branch outlets, 10% of total flow was directed to the BCA outlet, while another 10% of the total flow was equally distributed between the LCCA and LSA outlet28. The pressure at the outlet of the descending aorta was set to 0. The mean Reynolds number is 1,492, with the maximum Reynolds number of 5,966 during peak systole.

LES model

The LES was carried out with the wall-adapting local eddy-viscosity (WALE), which is one of the major subgrid-scale (SGS) models29. Although the WALE model is an algebraic eddy viscosity model, it is capable of handling transition to turbulent flow. The governing equations for incompressible fluid flow in LES are derived by filtering the Navier-Stokes equations as follows:

where, the subgrid-scale Reynolds stress tensor is \(\:{\tau\:}_{ij}=\stackrel{-}{{u}_{i}{u}_{j}}-{\stackrel{-}{u}}_{i}{\stackrel{-}{u}}_{j}\). This subgrid-scale Reynolds stress through the eddy viscosity hypothesis is computed as:

Here, \(\:{\delta\:}_{ij}\) is the Kronecker delta function. In the WALE model, the subgrid-scale eddy viscosity \(\:{\nu\:}_{\text{s}\text{g}\text{s}}\) is computed as:

Note that for this simulation, the computational grid satisfies direct numerical simulation (DNS) criteria, with delta x+, yPlus, delta z + all being much smaller than 1. The LES model is expected to have minimal impact, with the subgrid scale (SGS) turbulent viscosity being very small30.

Note that for this simulation. The computational grid satisfies direct numerical simulation (DNS), delta x+, yPlus, delta z + is much smaller than 1. The LES model is expected to only slightly affect the simulation through very small values of subgrid scale turbulent viscosity30.

where \(\:{C}_{k}\)is a model constant which set to 0.09431, and \(\:{k}_{\text{s}\text{g}\text{s}}\) is the subgrid-scale kinetic energy, which can be computed as follows:

where \(\:{C}_{w}\)is a constant that set to 0.56,29,31. \(\:{S}_{ij}^{d}\) is the trace free symmetric part of the square of the velocity gradient tensor, computed as follows:

Finally substituting Eq. (4) into Eq. (3), that summarized as:

Temporal discretization was applied with a second-order backward Euler scheme, and the spatial discretization used second-order central differencing6. To reduce the computational time, initial conditions were set using the k-ω SST model with a lower uniform velocity corresponding to a Reynolds number of 67. Subsequently, a timestep of dt = 1.0 × 10−5 s was employed for LES, maintaining a Courant-Friedrichs-Lewy (CFL) number below 0.5. To ensure fully developed turbulent flow structures in the aorta and convergence of the ensemble average, the initial 10 cycles were discarded as the transient phase, and the data from the subsequent 30 cycles were averaged. For the postprocessing, wall shear stress (WSS), time-average wall shear stress (TAWSS), and oscillatory shear index (OSI) were described as follows.

where, R is shear-stress symmetric tensor, n is surface normal vector (into the domain).

Under the pulsatile flow waveform, the average across multiple cardiac cycles is calculated for each time point \(\:t\) as follows:

where: \(\:\langle u\left(t\right)\rangle\) is the ensemble-averaged velocity at time t over multiple cardiac cycles. \(\:u\left(t\right)\) is the instantaneous velocity at time \(\:t\) in the \(\:{n}^{th}\) cycle. N is the total number of cardiac cycles.

In addition, turbulent kinetic energy (TKE) was defined as follows:

where, \(\:{u}^{{\prime\:}}\left(t\right)\) are the fluctuating velocity vector.

The energy distribution of velocity fluctuations across different flow frequencies was analyzed using the method proposed by Chnafa et al.32 followed by a Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT) approach as described by Natarajan et al.33. The STFT is defined as:

Where \(\:x\left[n\right]\) is the input velocity signal, \(\:\omega\:\left[n\right]\) is the Hann window, \(\:f\) is the frequency.

Simulation was conducted using OpenFOAM 4.1 on the Nurion supercomputing system at Korea Institute of Science and Technology Information (KISTI) in Daejeon, Korea. The system features Intel Xeon 6148 (Skylake) processors with a computational performance of 1.536 TFLOPS and utilized 128 nodes for the simulation.

Results

Flow patterns

Figure 4 shows the ensemble-averaged velocity distribution at four phases of the cardiac cycle: near peak systole, mid-deceleration phase, end-systole, and diastole (refer to Fig. 3 for corresponding time points). During peak systole, the flow remains predominantly laminar with minimal fluctuation, and the high-velocity zone is primarily situated near the inner wall. However, during the mid-deceleration phase, the flow becomes unstable, indicating a transition to turbulence. This is accompanied by a shift of the high-velocity zone to the outer wall, which can be attributed to Dean flow caused by the significant curvature of the aortic arch. The division of flow into three major branches induces instability, creating low-velocity zones on the proximal wall and high-velocity zones on the distal wall of the branches. This flow division is a pivotal factor in the inception of turbulent flow, with the degree of turbulence potentially contingent on the flow division ratio. In the end-systolic phase, velocity declines markedly, and flow becomes chaotic, exhibiting no dominant flow direction. This is clearer in Figs. 5 and 6. Figures 5 and 6 illustrate the ensemble-averaged velocity contours in six distinct streamwise planes (refer to Fig. 1 for locations) and a three-dimensional representation of the velocity vectors, respectively. It is noteworthy that at the peak systolic phase (Fig. 6(a)), the flow is consistently oriented towards the inner wall and throughout the descending aorta. The peak Reynolds number is 6035, the Dean number is 2842. The pulsatile nature of blood flow leads to a sharp increase in velocity, causing higher inertia. This phenomenon directs the flow preferentially toward the inner wall, given this velocity pattern, it is anticipated that high WSS would occur on the inner wall during the peak systolic phase.

Ensemble-averaged velocity profiles on the mid-planes at various flow phases: (a) near pe systole (t = 0.102 s), (b) mid-deceleration phase (t = 0.302 s), (c) end-systole (t = 0.502 s), and (d) diastole (t = 0.702 s). Refer to Fig. 3 for the corresponding time points.

Ensemble-averaged velocity distribution at six cross sections in axial direction: (a) near peak systole (t = 0.102 s), (b) mid-deceleration phase (t = 0.302 s), and (c) end-systole (t = 0.502 s). Refer to Fig. 3 for the corresponding time points.

Instantaneous velocity vector at various flow phases: (a) near peak systole (t = 0.102 s), (b) mid-deceleration phase (t = 0.302 s), (c) end-systole (t = 0.502 s), and (d) diastole (t = 0.702 s). Refer to Fig. 3 for the corresponding time points.

During the mid-deceleration phase (Fig. 6(b)), As the pulsatile flow rate decreases, secondary flow and flow separation are present due to the interaction between centrifugal forces and viscous effects in the fluid, causing blood flow to shift toward the external region of the aorta, demonstrating characteristics of Dean flow. The mean Reynolds number for the whole period is 1593, and the mean Dean number is 750. Note that the velocity vector size was magnified for better visualization due to the low velocity in end-systole (Fig. 6(c, d)). During this phase, reverse flow and highly disturbed, complex flow patterns are observed.

The flow patterns in the aortic arch are visualized through streamlines at four different phases of the cardiac cycle, as shown in Fig. 7. During the acceleration phase, the helical flow begins from the ascending aorta and follows the inner wall of the aortic arch. As the flow transitions to the deceleration phase, the intensity of the helical flow decreases, and the highest velocity shifts towards the outer wall of the descending aorta. This shift leads to the formation of many small eddies along the inner wall of the aortic arch. At diastole, rotational and recirculating secondary flows are observed but are relatively small in magnitude.

Streamlines at various flow phases: (a) near peak systole (t = 0.102 s), (b) mid-deceleration phase (t = 0.302 s), (c) end-systole (t = 0.502 s), and (d) diastole (t = 0.702 s). Refer to Fig. 3 for the corresponding time points.

Turbulence characteristics

Figure 8 shows the eddy viscosity distribution at four different phases of cardiac cycle (refer to Fig. 3 for the corresponding time points), indicating the turbulence intensity. In the near peak systolic phase, the eddy viscosity is almost zero within the aorta, indicating laminar flow. However, the eddy viscosity is rather high in the major branches, particularly near the proximal wall of the branches, indicating stronger turbulence in the branches compared to the aortic arch. In the mid-deceleration phase, the eddy viscosity increases, suggesting the development of stronger turbulence in the inner wall of the aortic arch region, which remains high until the distal region of the descending aorta. By the end-systole, turbulence decreases, spreading more evenly throughout the aorta and mostly disappears by the diastolic phase. This is more evident in the transverse vorticity plot in Fig. 9. During peak systole, vorticity is predominantly observed in the three branches and the inner wall of the aortic arch, adhering closely to its curvature. In the branches, turbulence continues to propagate upwards, but due to the short length of the branches, the full effect of turbulence has not fully appeared. Initially, small-scale vortical structures exhibit well-organized laminar flow with uniform patterns. However, by the mid-deceleration phase, there is a transition from these organized and laminar patterns to larger and irregular vortical structures. The vortices at the inner wall of the aortic arch are notably large and concentrated. The branches of the arch significantly contribute to instability of flow resulting in development of small-scale vortices, facilitating their spread downward to the bottom of the descending aorta. During diastole, the strength of the vortices decreases and eventually disappears with returning to laminar flow.

Subgrid-scale eddy viscosity \(\:{\nu\:}_{\text{s}\text{g}\text{s}}\) on the mid-planes at various flow phases: (a) near peak systole (t = 0.102 s), (b) mid-deceleration phase (t = 0.302 s), (c) end-systole (t = 0.502 s), and (d) diastole (t = 0.702 s). Refer to Fig. 3 for the corresponding time points.

Transverse vorticity distribution on the mid-planes at various flow phases: (a) near peak systole (t = 0.102 s), (b) mid-deceleration phase (t = 0.302 s), (c) end-systole (t = 0.502 s), and (d) diastole (t = 0.702 s). Refer to Fig. 3 for the corresponding time points.

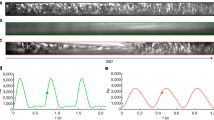

Time traces of velocity magnitude at six different locations (a)-(f), (Refer Fig. 1 for locations) are shown in Fig. 10. We can roughly determine the location and intensity of the transitional flow fluctuations. Flow disturbance with random fluctuations are observed at locations (b)–(f), with the highest fluctuations at the distal point (c). Fluctuations were present only during the mid-deceleration and end-systole phases, with no significant disturbances during diastole. Note that the velocity amplitude at location (a) is greater than the velocity amplitude at locations (b)-(f), due to the dean flow which shifts the peak away from the centerline where the trace data were collected. This indicates that turbulence is likely to occur in the aortic arch during the mid-deceleration phase.

left: Time traces of velocity magnitude at six streamwise locations for four cardiac cycles. Right: Time-frequency representation of the Power Spectral Density (PSD) in log scale of the velocity fluctuations at six locations (see Fig. 1).

The resulting spectrograms were phase-averaged over 30 cycles to improve accuracy, as shown in Fig. 10. In all phases, the Power Spectral Density (PSD) values gradually dissipate over time, with the low-frequency band retaining energy longer than the mid- and high-frequency ranges. The maximum velocity is 1.38 m/s, with the frequency maintained between 100 and 120. Point a highlights a broader and more concentrated low-frequency range, occupying approximately 0.2 T. Points b and c show that the PSD contributions are more widespread, with maximum velocities of 1.2 m/s and 1 m/s, respectively, and frequencies maintained between 50 and 75. Low-frequency components also appear between 0.2 s and 0.5 s, with velocity fluctuations ranging from 0.15 m/s to 0.6 m/s, exhibiting highly fluctuating distributions. Points d, e, and f display a narrower energy distribution within the 0.2 s to 0.4 s interval, concentrated in the low-frequency band. The frequency of velocity fluctuations decreases and becomes concentrated in the low-frequency band below 20 Hz.

Figure 11 shows the turbulent kinetic energy (TKE) at four phases of cardiac cycle (refer to Fig. 3 for the corresponding time points). TKE provides a valuable way to quantify the energy distribution in a turbulent flow field and is a critical metric in understanding the dynamics of turbulent systems. At peak systole there is no significant concentration of high TKE anywhere in the aortic arch, indicating laminar flow or regions with very mild turbulence in this configuration. Turbulence originates in the aortic arch following the peak systole phase and further develops in the aortic arch and descending aorta during the mid-deceleration and end-systole phases, with the maximum turbulence intensity exceeding 25%. The increase in TKE may correspond to areas where the flow experiences higher shear stress or flow separation due to the curvature of the arch. Areas of higher TKE also occurred near the curvature of the descending aorta, which may be due to the complex flow dynamics caused by the curvature.

Wall shear stress and oscillatory shear index

Figure 12 depicts the WSS distribution at phases of the cardiac cycle: (a) near peak systole (t = 0.102 s), (b) mid-deceleration phase (t = 0.302 s), (c) end-systole (t = 0.502 s), and (d) diastole (t = 0.702 s). The peak value of WSS occurs at near peak systole followed by mid deceleration phase. During early peak systole, the maximum WSS reaches up to 30 Pa, predominantly on the inner walls of the ascending aorta, gradually decreasing along its length. At the junction of the three branch outlets, WSS peaks between 7 and 11 Pa. Transitioning into the mid-deceleration phase, high WSS shifts towards the center of the aortic arch, with lower values observed along the inner walls of the aortic arch. During peak systole, the high-velocity zone is predominantly near the inner wall in laminar flow, correlating with the maximum WSS observed along the inner walls of the aorta. The transition to the mid-deceleration phase indicates unstable flow and a shift of high velocity towards the outer wall due to Dean flow induced by the large aortic arch curvature. This change in flow dynamics likely contributes to the redistribution of WSS towards the center of the wall during this phase (Fig. 4a&b). The time-averaged WSS distribution in Fig. 13 highlights elevated levels concentrated at the mid-anterior and inner posterior walls of the aortic arch. This distribution can be attributed to the strong helical flow pattern in the aortic arch. Furthermore, Fig. 13 reveals elevated WSS at the proximal segments of arterial branches, notably with the LSA exhibiting the highest values.

Ensemble-averaged WSS distribution at various flow phases: (a) near peak systole (t = 0.102 s), (b) mid-deceleration phase (t = 0.302 s), (c) end-systole (t = 0.502 s), and (d) diastole (t = 0.702 s). Refer to Fig. 3 for the corresponding time points.

Figure 14 illustrate the distribution of the oscillatory shear index (OSI) at four different phases of the cardiac cycle. During the peak systole, the flow is mostly streamlined, especially in the main arterial segment, leading to minimal oscillation in the shear stress direction. During the mid-deceleration phase, as the flow velocity decreases, there is an increase in oscillatory behavior, possibly due to developing flow separation and recirculation around these complex regions. The higher OSI values in this phase indicate the onset of flow disturbances, particularly at the branch junction and along the inner curvature of the aortic arch. In the diastolic phase, low and oscillating wall shear stresses are observed in the aortic arch and descending aorta.

Discussion

It is well established that the blood flow within a healthy aorta exhibits laminar flow, while the presence of turbulence is well-documented in patients with obstructive diseases in major vessels. However, catheter-based measurements in both human and canine studies have demonstrated that turbulence can develop in the aorta not only in the presence of disease but also with normal aortic valves8,34,35. Despite these observations, comprehensive description of turbulence in a healthy aorta has been lacking.

In this study, LES was employed to investigate turbulent flow characteristics in an idealized thoracic aortic model, with the focus on analyzing turbulence development and its extent in the aorta. This research enhances the broader understanding of cardiovascular health and disease progression, particularly in relation to conditions such as aortic dissection, aortic aneurysm and atherosclerotic stenosis. By examining the mechanisms and extent of hemodynamic changes during the transition from laminar to turbulent flow, this research offers critical implications for clinical management and treatment strategies.

In recent years, biomechanical research has increasingly focused on aortic flow through steady-state simulations employing various CFD models and patient-specific geometries of aortas36,37,38,39. While steady-state simulations show overall wall WSS behavior, they fail to capture the dynamic changes induced by pulsatile blood velocity, especially in regions such as the aortic arch and branch junctions40. These areas are significantly influenced by the acceleration phase where turbulent effects are pronounced, particularly at the curved section of the aorta. Some studies have considered the k-ε and k-ω models, which provide mean values of turbulence parameters and overall flow behavior41,42,43. However, small eddies in transitional flow increase WSS, potentially contributing to further aneurysm dilation, as the aorta adjusts its diameter to maintain shear stress below physiological thresholds44. In medical contexts with relatively high Reynolds numbers, high-resolution visualization and accuracy are crucial. Reynolds-Averaged Navier-Stokes (RANS) models are based solely on mean flow equations, relying on averaged quantities to approximate turbulence effects, which are the least computationally expensive turbulence modeling methods45. In contrast, Direct Numerical Simulation (DNS) represents the gold standard of simulation because it accounts for the effects of every scale of eddy when solving the flow equations. This approach maintains high fidelity by using computational cells smaller than or equal to the size of the smallest eddy, but it demands substantial computational resources46. DNS has been applied effectively in various studies: Dimakopoulos47 performed a DNS analysis on a 2D stent-type aortic valve, while Lee et al.48 used the spectral element method to simulate weakly turbulent flow in a patient-specific stenosed carotid bifurcation, predicting the complex flow field, turbulence levels, and distribution of hemodynamic parameters. Tullio et al.49 conducted a detailed DNS flow analysis on an aortic bileaflet mechanical heart valve, verifying the strong agreement between DNS and experimental results. Despite its accuracy, DNS is limited by its high computational cost. LES, which resolves larger turbulent eddies while modeling smaller ones, offers a more computationally efficient alternative to DNS. This method captures most of the flow dynamics while significantly reducing computational costs compared to DNS.

The LES conducted in our study provides detailed insights into the complex flow patterns in a generic thoracic aorta. During the acceleration phase, flow in the aorta is predominantly laminar from the ascending aorta to the aortic arch. However, during the mid-deceleration phase, there was a noticeable transition from well-organized laminar flow patterns observed during peak systole to small-scale irregular vortical structures. The aortic arch appears to be the beginning of the transition from laminar to turbulent flow. This transition is crucial, as it is characterized by high turbulence intensity and elevated shear stress, which can lead to potential vascular risks. High velocity fluctuations during this transition can lead to increased shear stress and vibrations in the aortic wall, potentially damaging the vessel and may contribute to vascular occlusion50. Our observations of complex vortices and reverse flow in the aortic arch during this transition are consistent with the findings of Fukuda et al.51 from PIV experiments, demonstrating a similar flow pattern. Helical flow is observed in the ascending aorta through streamlines plots in our study. A similar helical flow pattern was also observed in MRI flow filed study by Kilner et al.52, and CFD study by Tse et al.53 which validates our qualitative results.

In our simulation results, we observed that the high TAWSS consistently remains on the inner wall near the aortic arch. In this region, a potential inverse correlation between TAWSS and OSI is evident: areas with high TAWSS exhibit low OSI values, while areas with low TAWSS display increased OSI. This observation is in agreement with the findings reported by Wang et al.54,55. This combination of low TAWSS and high OSI is likely associated with arterial thrombus accumulation.

And it is also elevated WSS can be a contributing factor to the development of aortic dissection. For type A dissection, which involves the ascending aorta and aortic arch, we observed high WSS at the proximal ascending aorta and the aortic arch. These coincide with the predilection sites for aortic dissection reported by Chi et al.36. High WSS is also observed at the proximal segments of the arterial branches. Notably LSA exhibits higher WSS compared to the BCA and LCCA, indicating a potentially higher risk of tearing at the LSA. Furthermore, the elevated WSS at the proximal segments of arterial branches is associated with typical locations reported for atherosclerotic lesions in the thoracic aorta56.

For type B dissection, which typically affects the descending aorta, we observed high WSS at the entrance and distal location of the descending aorta. This high WSS is consistent with known high-risk sites for type B dissection. However, due to the complex nature of type B aortic dissection and the variability in patient-specific anatomy, while high WSS might contribute to wall thinning or increased biological stress, accurately quantifying and predicting the risk of type B aortic dissection remains challenging in healthy aortas57,58. In addition to aortic dissection, the regions of high WSS in our study, particularly near the aortic arch and branch bifurcations, may also be one of the contributing factors in the formation of aortic aneurysms. The persistent elevated WSS in these areas can lead to localized degeneration of the aortic wall, which, over time, may result in vessel wall dilation and an increased risk of aneurysm formation.

The diffusion of vorticity during mid-deceleration and end-systole results in turbulent flow with repeated reverse flow, which leads to repeated oscillations of WSS. These oscillating can contribute to the development of atherosclerosis, as studies have shown that low-level and oscillating WSS can induce endothelial changes, contributing to plaque formation59,60,61, which may subsequently lead to thrombus formation62,63,64. In our study, WSS levels decrease significantly from systole to the beginning of diastole, with higher shear stress localized near the branches and the inner curvature of the aortic arch. These findings are consistent with the LES results of Lantz et al.6.

Despite the comprehensive insights gained from our study, several limitations should be noted. Our study does not account for individual variations in aortic anatomy. While subject-specific models offer precise representations of individual anatomy, they may not be as widely applicable. An idealized model, such as ours, offers general insights that can be relevant to a broad range of individuals. While Wang65 suggested that deformable walls can significantly affect flow characteristics, particularly in the aorta, where the correlation between wall shear stress (WSS) and flow velocity may be altered. Our model assumes rigid walls and Newtonian fluid. While the rigid wall assumption may not fully capture the dynamic interactions between the flow and the vessel wall, Alimohammadi et al.66noted that this assumption in CFD can slightly overestimate WSS. However, it does not significantly alter the overall WSS distribution. Comparisons between fluid-structure interaction (FSI) and rigid wall models have shown similar temporal and spatial distributions of WSS, with errors in time-averaged WSS within 10%67. Moreover, a recent study reported that flow patterns and time-averaged WSS (TAWSS) distributions from FSI models were qualitatively comparable to those from rigid wall simulations, with the maximum difference being less than 0.25 mmHg68. Although non-Newtonian and Newtonian fluids exhibit different behaviors, many studies have shown similar vortex structures and WSS distributions for both type of fluids, with the main differences primarily observed in low Reynolds number regions. Therefore, the Newtonian fluid assumption is appropriate for simulating flow in arteries with high Reynolds numbers69,70,71.We used a predefined flow division (10% of the total flow was directed to the BCA, and 10% was equally divided between the LCCA and LSA). This approach may not fully reflect the natural variations in flow distribution among individuals. Anatomical differences can result in varying flow distribution, and incorporating subject-specific flow data could provide a more accurate representation of the blood flow dynamics within the aorta72. Lastly, the zero pressure boundary condition cannot predict the flow behavior caused by resistance; therefore, the outlet boundary condition utilizing the Windkessel model may offer improved accuracy in future investigations.

Conclusion

In this study, we employed LES to examine the transition from laminar to turbulent flow in an idealized thoracic aortic model, with a particular focus on the development of turbulence and its extent within a healthy aorta. Our findings revealed that turbulence may occur even in a healthy aorta, especially within the aortic arch and descending aorta. As turbulence develops, it generates oscillatory and secondary flow patterns, which significantly influence the intensity and distribution of wall shear stress (WSS). This study advances the fundamental understanding of the transition to turbulence, emphasizing its dependence on aortic geometry under pulsatile flow conditions, even in the absence of pathological changes. Future research could involve the use of direct numerical simulation (DNS) on subject-specific models to validate and extend these results, offering a more detailed comparison of hemodynamic characteristics and a deeper exploration of turbulence variations in different subject-specific environments.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Change history

25 March 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95231-3

References

Maton, A. et al. Human Biology Health (Prentice Hall, 1995).

Drake, R. L., Vogl, W. & Adam, W. M. Mitchell & Henry Gray. Gray’s Anatomy for Students 2nd edn (Churchill Livingstone (Elsevier, 2010).

Matsuzawa, T., Gao, F., Qiao, A., Ohta, O. & Ok, H. Numerical Simulation in Aortic Arch Aneurysm. in Etiology, Pathogenesis and Pathophysiology of Aortic Aneurysms and Aneurysm RuptureInTech, (2011). https://doi.org/10.5772/18566

Ku, D. N., Giddens, D. P., Zarins, C. K. & Glagov, S. Pulsatile flow and atherosclerosis in the human carotid bifurcation. Positive correlation between plaque location and low oscillating shear stress. Arteriosclerosis: Official J. Am. Heart Association Inc. 5, 293–302 (1985).

Chiu, J. J., Usami, S. & Chien, S. Vascular endothelial responses to altered shear stress: pathologic implications for atherosclerosis. Ann. Med. 41, 19–28 (2009).

Lantz, J., Gårdhagen, R. & Karlsson, M. Quantifying turbulent wall shear stress in a subject specific human aorta using large eddy simulation. Med. Eng. Phys. 34, 1139–1148 (2012).

Ha, H. et al. Age-related vascular changes affect turbulence in aortic blood flow. Front. Physiol. 9, (2018).

Stein, P. D. & Sabbah, H. N. Turbulent blood flow in the ascending aorta of humans with normal and diseased aortic valves. Circ. Res. 39, 58–65 (1976).

Sundin, J. et al. Improved efficiency of Intraventricular Blood Flow Transit under Cardiac stress: a 4D Flow Dobutamine CMR Study. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 7, (2020).

Sundin, J., Bustamante, M., Ebbers, T., Dyverfeldt, P. & Carlhäll, C. J. Turbulent intensity of Blood Flow in the healthy aorta increases with dobutamine stress and is related to Cardiac output. Front. Physiol. 13, (2022).

Arzani, A., Dyverfeldt, P., Ebbers, T. & Shadden, S. C. In vivo validation of numerical prediction for turbulence intensity in an aortic coarctation. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 40, 860–870 (2012).

Pietrasanta, L., Zheng, S., De Marinis, D., Hasler, D. & Obrist, D. Characterization of turbulent Flow behind a transcatheter aortic valve in different implantation positions. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 8, (2022).

Shahcheranhi, N., Dwyer, H. A., Cheer, A. Y., Barakat, A. I. & Rutaganira, T. Unsteady and three-dimensional simulation of blood flow in the human aortic arch. J. Biomech. Eng. 124, 378–387 (2002).

Benim, A. C. et al. Simulation of blood flow in human aorta with emphasis on outlet boundary conditions. Appl. Math. Model. 35, 3175–3188 (2011).

Casacuberta, J. J. Hemodynamics in the Thoracic Aorta Using OpenFOAM: 4d PCMRI versus CFD (International Center for Numerical Methods in Engineering, 2015).

Zakaria, M. S. et al. A cartesian non-boundary fitted grid method on complex geometries and its application to the blood flow in the aorta using OpenFOAM. Math. Comput. Simul. 159, 220–250 (2019).

Becsek, B., Pietrasanta, L. & Obrist, D. Turbulent systolic Flow downstream of a Bioprosthetic aortic valve: velocity Spectra, Wall Shear stresses, and turbulent dissipation rates. Front. Physiol. 11, (2020).

Büchner, D., Manchester, E. L. & Xu, X. Y. Analysis of the directional and spectral distributions of kinetic energy in aortic blood flow. Phys. Fluids 36, (2024).

Manchester, E. L. et al. Aortic valve neocuspidization and bioprosthetic valves: evaluating turbulence haemodynamics. Comput. Biol. Med. 171, (2024).

Saqr, K. M. & Zidane, I. F. On non-kolmogorov turbulence in blood flow and its possible role in mechanobiological stimulation. Sci. Rep. 12, (2022).

Qiao, Y., Luo, K. & Fan, J. Heat transfer mechanism in idealized healthy and diseased aortas using fluid-structure interaction method. Biomech. Model. Mechanobiol. 22, 1953–1964 (2023).

Qiao, Y., Fan, J. & Luo, K. Mechanism of blood flow energy loss in real healthy aorta using computational fluid-structure interaction framework. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 192, 103939 (2023).

Lopes, D. et al. Comparison of RANS and LES turbulent flow models in a real stenosis. Int. J. Heat. Fluid Flow. 107, 109340 (2024).

Manchester, E. L. et al. Analysis of Turbulence effects in a patient-specific aorta with aortic valve stenosis. Cardiovasc. Eng. Technol. 12, 438–453 (2021).

Vasava, P., Jalali, P., Dabagh, M. & Kolari, P. J. Finite element modelling of pulsatile blood flow in idealized model of human aortic arch: Study of hypotension and hypertension. Comput Math Methods Med (2012). (2012).

Morbiducci, U., Ponzini, R., Gallo, D., Bignardi, C. & Rizzo, G. Inflow boundary conditions for image-based computational hemodynamics: impact of idealized versus measured velocity profiles in the human aorta. J. Biomech. 46, 102–109 (2013).

Pirola, S. et al. Computational study of aortic hemodynamics for patients with an abnormal aortic valve: the importance of secondary flow at the ascending aorta inlet. APL Bioeng. 2, 026101 (2018).

Vignon-Clementel, I. E., Figueroa, A., Jansen, C., Taylor, C. A. & K. E. & Outflow boundary conditions for three-dimensional finite element modeling of blood flow and pressure in arteries. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 195, 3776–3796 (2006).

Nicoud, F. & Ducros, F. Subgrid-scale stress modelling based on the Square of the velocity gradient Tensor. Flow. Turbul. Combust. 62, 183–200 (1999).

Paul, M. C. & Molla, M. M. Investigation of physiological pulsatile flow in a model arterial stenosis using large-eddy and direct numerical simulations. Appl. Math. Model. 36, 4393–4413 (2012).

Weickert, M., Teike, G., Schmidt, O. & Sommerfeld, M. Investigation of the LES WALE turbulence model within the lattice Boltzmann framework. Comput. Math. Appl. 59, 2200–2214 (2010).

Chnafa, C., Mendez, S. & Nicoud, F. Image-based simulations show important Flow fluctuations in a normal left ventricle: what could be the implications? Ann. Biomed. Eng. 44, 3346–3358 (2016).

Natarajan, T., MacDonald, D. E., Najafi, M., Khan, M. O. & Steinman, D. A. On the spectrographic representation of cardiovascular flow instabilities. J. Biomech. 110, 109977 (2020).

Kikkawa, S., Yoshikawa, T., Tanishita, K. & Sugawara, M. Measurement of Turbulenoe Intensity in the Center of the Canine Ascending Aorta with a Hot-Film anemometer 1. (1983). http://biomechanical.asmedigitalcollection.asme.org/

Hanai, S., Yamaguchi, T. & Kikkawa, S. TURBULENCE IN THE CANINE ASCENDING AORTA AND THE BLOOD PRESSURE. BIORHEOLOGY vol. 28 (1991).

Chi, Q., He, Y., Luan, Y., Qin, K. & Mu, L. Numerical analysis of wall shear stress in ascending aorta before tearing in type A aortic dissection. Comput. Biol. Med. 89, 236–247 (2017).

Aycan, O., Topuz, A. & Kadem, L. Evaluating uncertainties in CFD simulations of patient-specific aorta models using Grid Convergence Index method. Mech. Res. Commun. 133, 104188 (2023).

Perinajová, R. et al. Geometrically induced wall shear stress variability in CFD-MRI coupled simulations of blood flow in the thoracic aortas. Comput. Biol. Med. 133, (2021).

Vinoth, R. et al. Steady and Transient flow CFD Simulations in an Aorta Model of Normal and Aortic Aneurysm Subjectsvol. 50629–43 (Springer, 2019). in Lecture Notes in Electrical Engineering.

Kousera, C. A. et al. A numerical study of aortic flow stability and comparison with in vivo flow measurements. J. Biomech. Eng. 135, (2013).

Khanafer, K. M., Bull, J. L. & Berguer, R. Fluid-structure interaction of turbulent pulsatile flow within a flexible wall axisymmetric aortic aneurysm model. Eur. J. Mech. B. Fluids. 28, 88–102 (2009).

Khanafer, K. M., Bull, J. L., Upchurch, G. R. & Berguer, R. Turbulence significantly increases pressure and fluid shear stress in an aortic aneurysm model under resting and Exercise Flow conditions. Ann. Vasc Surg. 21, 67–74 (2007).

Ryo et al. Investigations into the potential of using Open Source CFD to analyze the differences in Hemodynamic Parameters for Aortic Dissections (healthy versus Stanford Type A and B). Ann. Vasc Surg. 79, 310–323 (2022).

Giddens, D. P., Zarins, C. K. & Glagov, S. Response of arteries to Near-Wall Fluid Dynamic Behavior. Appl. Mech. Rev. 43, S98–S102 (1990).

Wolfgang, R. Turbulence modeling and Simulation in Hydraulics: a historical review. J. Hydraul. Eng. 143, 03117001 (2017).

Tiselj, I., Flageul, C., Oder, J. & Flageul, C. Direct Numerical Simulation and Wall-resolved large Eddy Simulation in Nuclear Thermal Hydraulics. Nucl. Technol. 1–15 https://doi.org/10.1080/00295450.2019.1614381ï (2019).

Dimakopoulos, Y., Bogaerds, A. C. B., Anderson, P. D., Hulsen, M. A. & Baaijens, F. P. T. Direct numerical simulation of a 2D-stented aortic heart valve at physiological flow rates. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Engin. 15, 1157–1179 (2012).

Lee, S. E., Lee, S. W., Fischer, P. F., Bassiouny, H. S. & Loth, F. Direct numerical simulation of transitional flow in a stenosed carotid bifurcation. J. Biomech. 41, 2551–2561 (2008).

De Tullio, M. D., Cristallo, A., Balaras, E. & Verzicco, R. Direct numerical simulation of the pulsatile flow through an aortic bileaflet mechanical heart valve. J. Fluid Mech. 622, 259–290 (2009).

Asbury, C. L., Ruberti, J. W., Bluth, E. I. & Peattie, R. A. Experimental investigation of steady flow in rigid models of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 23, 29–39 (1995).

Fukuda, I. et al. Breakdown of Atheromatous Plaque due to Shear Force from arterial perfusion cannula. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 84, e17–e18 (2007).

Kilner, P. J., Yang, G. Z., Mohiaddin, R. H., Firmin, D. N. & Longmore, D. B. Helical and retrograde secondary flow patterns in the aortic arch studied by three-directional magnetic resonance velocity mapping. Circulation 88, 2235–2247 (1993).

Tse, K. M. et al. A computational fluid dynamics study on geometrical influence of the aorta on haemodynamics. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 43, 829–838 (2013).

Wang, H., Balzani, D., Vedula, V., Uhlmann, K. & Varnik, F. On the potential self-amplification of Aneurysms due to tissue degradation and blood Flow revealed from FSI simulations. Front. Physiol. 12, (2021).

Wang, H., Uhlmann, K., Vedula, V., Balzani, D. & Varnik, F. Fluid-structure interaction simulation of tissue degradation and its effects on intra-aneurysm hemodynamics. Biomech. Model. Mechanobiol. 21, 671–683 (2022).

Wasilewski, J., Głowacki, J. & Poloński, L. Not at random location of atherosclerotic lesions in thoracic aorta and their prognostic significance in relation to the risk of cardiovascular events. Polish Journal of Radiology vol. 78 38–42 Preprint at (2013). https://doi.org/10.12659/PJR.883944

Marrocco-Trischitta, M. M. et al. Prevalence of type III arch configuration in patients with type B aortic dissection. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 56, 1075–1080 (2019).

Wen, J. et al. Risk evaluation of type B aortic dissection based on WSS-based indicators distribution in different types of aortic arch. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 221, (2022).

Burris, N. S. & Hope, M. D. 4D Flow MRI applications for aortic disease. Magn. Reson. Imaging Clin. N Am. 23, 15–23 (2015).

Cheng, C. et al. Atherosclerotic lesion size and vulnerability are determined by patterns of fluid shear stress. Circulation 113, 2744–2753 (2006).

Slager, C. J. et al. The role of shear stress in the generation of rupture-prone vulnerable plaques. Nat. Clin. Pract. Cardiovasc. Med. 2, 401–407 (2005).

Motomiya, M. & Karino, T. Flow patterns in the human carotid artery bifurcation. Stroke 15, 50–56 (1984).

Giddens, D. P., Mabon, R. F. & Cassanova, R. A. Measurements of disordered flows distal to subtotal vascular stenoses in the thoracic aortas of dogs. Circ. Res. 39, 112–119 (1976).

Lee, B. K. et al. Hemodynamic effects on atherosclerosis-prone coronary artery: Wall Shear stress / rate distribution and Impedance Phase Angle in Coronary and aortic circulation. Yonsei Med. J. 42, 375 (2001).

Wang, H., Krüger, T. & Varnik, F. Effects of size and elasticity on the relation between flow velocity and wall shear stress in side-wall aneurysms: a lattice Boltzmann-based computer simulation study. PLoS One 15, (2020).

Alimohammadi, M., Agu, O., Balabani, S. & Díaz-Zuccarini, V. Development of a patient-specific simulation tool to analyse aortic dissections: Assessment of mixed patient-specific flow and pressure boundary conditions. Med. Eng. Phys. 36, 275–284 (2014).

Reymond, P., Crosetto, P., Deparis, S., Quarteroni, A. & Stergiopulos, N. Physiological simulation of blood flow in the aorta: comparison of hemodynamic indices as predicted by 3-D FSI, 3-D rigid wall and 1-D models. Med. Eng. Phys. 35, 784–791 (2013).

Zhu, Y., Mirsadraee, S., Rosendahl, U., Pepper, J. & Xu, X. Y. Fluid-structure Interaction simulations of repaired type a aortic dissection: a comprehensive comparison with rigid Wall models. Front. Physiol. 13, (2022).

Guerciotti, B. & Vergara, C. Computational Comparison between Newtonian and non-Newtonian Blood Rheologies in Stenotic Vesselsvol. 84169–183 (Springer, 2018). in Lecture Notes in Applied and Computational Mechanics.

Dutra, R. F., Zinani, F. S. F., Rocha, L. A. O. & Biserni, C. Effect of non-newtonian fluid rheology on an arterial bypass graft: a numerical investigation guided by constructal design. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 201, 105944 (2021).

Keslerová, R. Numerical modeling of generalized newtonian fluids flow in S-type geometry of bypass. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 429, 115237 (2023).

Wang, H., Krüger, T. & Varnik, F. Geometry and flow properties affect the phase shift between pressure and shear stress waves in blood vessels. Fluids 6, (2021).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program, funded by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF). (2020R1I1A3066617)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.C, K.L, and S.L contributed to the conception and design of the study. K.C performed the simulation and the statistical analysis for the study. K.C, S.A and S.L wrote the first draft of the manuscript. K.C, S.A, K.L and S.L revised it critically for important intellectual content. All authors contributed to the manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: In the original version of this Article, the author name Sang-Wook Lee was inadvertently duplicated in the author list.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cheng, K., Akhtar, S., Lee, K.Y. et al. Characteristics of transition to turbulence in a healthy thoracic aorta using large eddy simulation. Sci Rep 15, 3236 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86983-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86983-z

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Microtubules and mechanosensing: key players in endothelial responses to mechanical stimuli

Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences (2025)