Abstract

Myocardial infarction with nonobstructive coronary arteries (MINOCA) constitutes 3–15% of all acute myocardial infarctions. Women are more frequently diagnosed with MINOCA, although the influence of sex on long-term outcomes is still unclear. In this study we aimed to compare sex-based differences in baseline characteristics and clinical outcomes in patients with suspected MINOCA. We have retrospectively analyzed 6063 patients diagnosed with MINOCA (3220 females and 2843 male patients) from combined 3 large polish registries (PL-ACS, SILCARD and AMI-PL). Male patients were significantly younger (63 (55–74) vs. 71 (61–79) years, p < 0.05) and less frequently diabetic (20.1% vs. 24.1%, p < 0.05). Mortality was significantly higher in male population (11.8% vs. 10.2%, p < 0.05 at 1 year and 17.6% vs. 15.0%, p < 0.05 at 3 years). Male sex was an independent predictor of both mortality (HR = 1.29; CI 1.11–1.51; p < 0.05) and myocardial infarction (HR = 1.39; CI 1.1–1.75, p < 0.05) at 3 years follow-up. All-cause readmission rates were similar in male and female patients both at 1 year (46.0% vs. 44.4, p = 0.2) and 3 years follow-up (56.4% vs. 56.5%, p = 0.93). However, cardiovascular readmissions were more prevalent in male patients at both timepoints (33.9% vs. 29.10%, p < 0.05 at 1 year, and 41.0% vs. 37.6%, p < 0.05 at 3 years). This large-scale registry-based analysis demonstrated higher 3 years rates of adverse events, including death and MI among male patients with suspected MINOCA.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

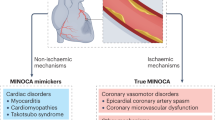

Myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary arteries (MINOCA) is described as the coexistence of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and non-obstructive coronary artery disease on coronary angiography1. MINOCA constitutes about 3-15% of all AMI cases and is diagnosed more frequently in women2,3,4. It is believed that the mechanism of MINOCA is multifactorial with microvascular causes (coronary microvascular spasm or embolism) or epicardial causes (coronary artery dissection/spasm, plaque erosions). However, some of the syndromes can potentially mimic MINOCA (for instance takotsubo syndrome, cardiomyopathies, myocarditis), therefore comprehensive diagnostic evaluation is important to exclude potential non-ischemic causes of myocardial injury5,6.

Whilst previous studies have investigated sex-based differences in MINOCA outcomes, their findings have been inconsistent. For example, Canton et al.7 showed that male patients were significantly younger and that the male sex was independently associated with a lower incidence of all major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (MACCE), with numerically lower incidence of all-cause deaths, stroke and re-hospitalizations due to hearth failure, and with higher number of re-AMI admissions. In contrast, the study of Gao et al.8 showed no significant differences in MACCE, although males were more frequently re-hospitalized due to heart failure and more often presented with stroke following discharge. The advantage of the above-mentioned studies is that there is strict and clear methodology to define MINOCA. In these studies, MINOCA was defined as the presence of MI with the absence of obstructive lesions in coronary arteries (lack of ≥ 50% obstruction). Moreover, in these studies the authors performed additional imaging diagnostics (CMR, chest CT) in patients with non-obstructive coronary arteries to exclude non-ischemic troponin elevation causes, acute aortic syndrome or pulmonary embolism when it was clinically suspected. The main disadvantage of previously-mentioned studies is the small number of patients which can potentially influence on sex-based differences in MINOCA outcomes and make their findings inconsistent. In view of disparate findings, our study aims to identify and describe sex differences in baseline characteristics and long-term outcomes in patients suspected of MINOCA using 3 large national Polish registries.

Methods

Data sources

For this study, we have retrospectively analyzed the data collected from three large registries: the Polish Registry of Acute Coronary Syndromes (PL-ACS), the Silesian Cardiovascular (SILCARD) Registry, and the Polish Nationwide Acute Myocardial Infarction Database (AMI-PL) and subsequently derived a heterogeneous group of 6063 patients with a working diagnosis of MINOCA.

PL-ACS is a national, multicenter, prospective observational registry. Data on all patients who underwent hospitalization due to ACS in Poland were included9. Registry was founded by Silesian Center of Hearth Diseases in Zabrze and the Polish Ministry of Health in October 2003 and it was harmonized with the European Cardiology Audit and Registration Data Standards (CARDS) in May 2004. Data for this study were collected from the patients hospitalized between 2006 and 2017 in 414 polish hospitals and they were inserted by physicians into the electronic system of the registry. The follow-up data was obtained from the National Health Fund.

The SILCARD registry was created by Silesian Center for Heart Diseases in Zabrze and the Regional Department of National Health Fund in Katowice. The main purpose was to perform a versatile analysis of patients hospitalized due to cardiovascular diseases in the Silesian Province10, a large region in the South of Poland, inhabited by about 3,8 million adults11. The registry enrolled all Silesian adult patients hospitalized between 2006 and 2016 in cardiology, cardiac surgery, vascular surgery, or diabetology units for any reason. In addition, it also contains patients hospitalized in the internal medicine wards or intensive care units with the principal diagnosis of cardiovascular disease (CVD)12, defined as any I code, J96 or R52 according to International Classification of Diseases (ICD).

The AMI-PL registry contains all cases of AMI in Poland that occurred between 2009 and 201413. Data were provided by the National Health Fund, the only public health insurer in Poland, who has signed contracts with both, public and private healthcare centers. The cases were selected according to primary diagnosis in the ICD as I21 or I22.

The institutional review board at each site approved all protocols. The registries were approved by the local Ethics Committee and meet the conditions of the Declaration of Helsinki. All the databases we used in our study were created in collaboration with the National Health Fund in Poland and had its approval for use. Additionally, the SILCARD database received approval from ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02743533), and the PL-ACS database was harmonized with the European Cardiology Audit and Registration Data Standards (CARDS). For the AMI-PL and SILCARD databases, data were provided by the National Health Fund based on ICD codes, and patient details were anonymized. For the PL-ACS database, patients signed an informed consent form for inclusion in the registry. All these databases were utilized for comprehensive analysis and databases did not affect the patients’ medical treatment.

Due to non-experimental, observational nature of the following study, the additional approval of the Bioethics Committee was not required. Also, because of the retrospective nature of the study, further informed consent from patients had not been obtained.

Study population

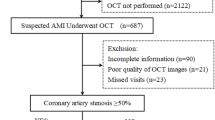

In this study we included all patients diagnosed with ST-elevated myocardial infarction (STEMI) and non-ST-elevated myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) in accordance to European Society of Cardiology, from databases: PL-ACD, SILCARD and AMI-PL. We excluded all patients younger than 18 years, with either a history of AMI or previous percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or coronary artery by-pass grafting (CABG). In this study, we only included patients who underwent coronary angiography, were not assigned to interventional treatment (PCI or CABG), and did not have > 50% stenosis in any coronary artery. Additionally, all patients diagnosed at admission with cardiac arrest, cardiogenic shock or pulmonary edema were excluded from the study. To summarize, we have included patients who underwent hospitalization due to AMI for the first time, with no previous history of coronary revascularization and with non-obstructive (< 50%) coronary stenosis visually estimated by the operators.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was performed with Statistica version 13 (Version 13.1, TIBCO Software Inc., Palo Alto, CA, USA). We conducted a 3-year follow-up starting from the date of the first day of hospitalization. We analyzed the primary endpoints, which were defined as death and myocardial infarction and secondary endpoints, defined as rehospitalizations during follow-up period. As rehospitalization we separately considered all-cause readmissions and cardiovascular readmissions. Also, the descriptive statistics were performed. We presented all qualitative variables as a percentage. The Chi square Pearson’s test was performed to obtain comparative analysis. The variables without normal distribution were presented as the median with the interquartile range. The variables with normal distribution were verified by the Shapiro–Wilk test. All groups were compared with the usage of the Mann–Whitney U test. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to perform the survival analysis. We used the Cox proportional hazards model to adjust 12- and 36-months mortality to the differences in the baseline characteristics. Baseline characteristics parameters that varied between the groups with p < 0.05 were analyzed by stepwise elimination (p < 0.05 to remain in the model). Results were presented as the hazard ratio (HR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI).

Results

Baseline characteristics

The cohort consisted of 6063 patients, with 3220 females and 2843 male patients (53.1%vs.46.9%) (Fig. 1). Several differences between female and male patients were observed. Males were younger (years (Q1-Q3): (63 (55–74) vs. 71 (61–79) years, p = < 0.05) and less frequently diabetic (20.1% vs. 24.1%, p < 0.05). Hypertension was less common in the male group (76.9% vs. 68.4%, p < 0.05).

Male patients were more likely to present with heart failure (9.07% vs. 6.98%, p = 0.05), previous peripheral artery diseases (5.2% vs. 3.2%, p < 0.05) and previous lung diseases (5.1% vs. 3.7%, p < 0.05). Males were less often obese (16.1% vs. 19.3%, p < 0.05). There were no significant differences in terms of previous stroke or previous kidney disease. The baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Medications at discharge

ASA and P2Y12 inhibitors were prescribed at discharge less frequently to men (respectively: 84.8% vs. 86.8%, p < 0.05 and 60.1% vs. 63.4%, p < 0.05). Furthermore, males received beta-blockers and statins less often (75.6% vs. 77.9%, p < 0.05 and 78.5% vs. 83.0%, p < 0.05). On the other hand, no statistical differences between men and women were observed in angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, nitrates, and oral anticoagulation treatment (69.5% vs. 70.2%, p = 0.670, 9.8% vs. 9.2%, p = 0.45 and 6.2% vs. 5.6%, p = 0.34). Medications at discharge are presented in Table 2.

Clinical outcomes

In-hospital mortality was not statistically different between groups (1.5 vs. 1.5%, p = 0.99). At both 1- and 3-years follow-up male patients had significantly higher rates of MI (4.7% vs. 3.2% p < 0.05 at 1 year and 7.0% vs. 5.5%, p < 0.05 at 3 years) (Fig. 2A). Male patients also presented a higher, all-cause mortality (11.8% vs. 10.2%, p < 0.05 at 1 year and 17.6 vs. 15.0, p < 0.05 at 3 years) (Fig. 2B). Comparable results were obtained in the group of patients who survived until hospital discharge (Fig. 2C and D). After correcting for the differences in baseline characteristics between the male and female population, multivariate analysis demonstrated that the Male sex was an independent predictor of re-MI at 3 years. Furthermore, male sex was independently associated with increased mortality at 3 years (HR = 1.38; CI 1.16–1.64; p < 0.05) (Fig. 3). Furthermore, landmark analysis of patients that survived until discharge at index hospitalization also demonstrated higher MI and all-cause mortality rates among male patients. There were no differences in rates of stroke. All-cause readmission rates were similar in both groups (46.1% in men vs. 44.4% in women, p = 0.20 at 1 year and 56.4% vs. 56.5%, p = 0.94 at 3 years). However, men more often experienced CV-related hospital readmissions (33.9% vs. 29.1% p < 0.05 at 1 year and 41.0% vs. 37.6%, p < 0.05 at 3 years). After performing a sub-analysis for both sexes, stratified by the median age, proportional results were observed between genders in the groups of patients below and above the median age. However, in patients older than the median age, there was a higher number of deaths and hospitalizations, which is associated with a greater risk on these patients (Kaplan-Meier curves, stratified by the median age are presented in Fig. 4).

Patient’s outcomes are summarized in Table 3. The readmission rates are summarized in Table 4. Sub-analysis for both sexes stratified by the median age are summarized in Table 5.

Discussion

In this largescale, retrospective study, we evaluated the impact of sex-based differences in baseline characteristics and clinical outcomes in patients with suspected MINOCA. The key finding was that at 3 years follow-up rates of adverse events, including death and MI, were higher among male patients presenting with MINOCA despite being significantly younger than female patients. Furthermore, multivariate analysis confirmed that male sex was one of the independent predictors of both death and MI at 3 years.

In large studies MINOCA patients constitute 3-15% of all AMI population2,3,4. This is consistent with our study in which MINOCA was present in 2.9% of patients (n = 6063) from the whole study group. Furthermore, the proportion of women in MINOCA is higher than men, ranging from 50 to 62%3,4,14,15,16,17. Our study demonstrated related results with larger proportion of women (53%) with a MINOCA working diagnosis. In our study female patients with MINOCA were an average of 8 years older than male patients. What is more, women more frequently presented with diabetes, hypertension, and obesity. In contrast male patients were more likely to have heart failure and a lower LVEF during admission analogous to previously published studies16,18.

Previously published studies demonstrated that in the MINOCA population in-hospital mortality amongst men and women were similar16,19. This was in keeping with the results of our study. In contrast, there is a paucity of data reporting long-term outcomes in the MINOCA patients. Previous studies demonstrated similar mortality in female and male patients. In contrast our study showed higher all-cause mortality in male patients than women during follow up (11.8% vs. 10.2%, p < 0.05 at 1 year and 17.6 vs. 15.0, p < 0.05 at 3 years). Even after correcting for the differences in baseline characteristics multivariate analysis demonstrated that the male sex was independently associated with increased mortality (HR = 1.38; CI 1.16–1.64; p < 0.05). AMI rates in long term observation tend to be similar in previously published papers between men and female patients in MINOCA patients8,20. However, our study demonstrated that at both 1- and 3-years follow-up male patients had significantly higher rates of subsequent AMI (4.7% vs. 3.2% p < 0.05 at 1 year and 7.0% vs. 5.5%, p < 0.05 at 3 years). Furthermore, multivariate analysis demonstrated that Male sex was an independent predictor of re-MI at 3 years (HR = 1.39; CI 1.1–1.75, p < 0.05).

There are physiological and pathophysiological differences in females and males that may impact differences in mortality between the sexes among MINOCA patients, but direct connections are not fully elucidated. It must be stressed that heart failure rate in male patients was significantly higher in the studied population, which might partially explain their worse prognosis. Furthermore, it cannot be excluded that in a substantial proportion of the analyzed population the initial diagnosis of increased cardiac biomarker levels due to cardiomyopathies might have been overlooked, which might partially impact the results. Also, it has been demonstrated previously that myocardial apoptosis in peri-infarct areas is higher in males dying late after AMI than in females, which may explain the more aggressive course of post-infarction HF in men and the relatively more benign post-infarction remodeling in women, potentially suggesting an increased resistance to ischemia in females21. Male patients were significantly less frequently prescribed with aspirin, P2Y12 inhibitors and statins at discharge, which indicate that they received less frequently optimal secondary prevention than female patients. Some studies show that in MINOCA patients statins, beta-blockers, DAPT and ACEI/ARB reduce all-cause death21,22,23 and statins, beta-blockers and ACEI/ARB reduce the risk of MACE22,24,25,26. This can also partially explain worse outcomes of male patients in our study because male patients less frequently were prescribed with ASA, P2Y12 inhibitors, ACE inhibitors, Beta-adrenolytic and statins. Furthermore, the undertreatment of the MINOCA patients in everyday practice should be emphasized. The phenomenon of re-AMI after MINOCA occurs in approximately 6–8% of patients. In a study by Ciliberti et al. re-AMI concerned almost 8% of MINOCA patients. Among these 41.7% showed obstructive coronary atherosclerosis and only 4.5% had low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) under 55 mg/dL during observation27. In another study by Nordenskjöld et al. 6.3% of MINOCA patients had re-AMI. The median time of readmission was 17 months28. Finally, the etiology of MINOCA is likely to differ between males and females and this may contribute to the differences in outcomes. Furthermore, CMR is a viable tool in distinguishing AMI from myocarditis or Takotsubo syndrome and plays a vital role in differentiating ischemic from non-ischemic mechanisms of etiology29,30. However, one of the limitations of our study was lack of CMR data and we cannot exclude that some of the patients could have been reclassified31. Potentially, the overlooked cardiomyopathies during the initial admission might explain the higher mortality in the male population. Moreover, ischemic cardiomyopathies are believed to have worse outcomes than non-ischemic cardiomyopathies32,33. A previous study demonstrated that the readmission rates due to unstable angina or heart failure in MINOCA population was similar in male and female patients15. The advantages of the presented study are evaluation of readmissions and their causes up to 3 years follow up. In our study all-cause readmission rates were similar in both groups although men more often experienced CV-related hospital readmissions at 1 and 3 years mostly driven by higher rates of CAD readmissions. Due to the gaps in literature, this topic requires further attention in future studies.

Limitations

We acknowledge certain limitations of this study. First, a universal, broad definition of MINOCA has been used, which encompassed individuals with suspected MINOCA. CMR was not routinely performed in patients included in our study, which may have caused non-ischemic causes to be missed. Furthermore, we lack the information on how many patients underwent further testing to determine the primary cause of MINOCA. Moreover, our research was limited by its observational nature. Another issue was the absence of intracoronary imaging, pressure or doppler wire, as well as provocative spasm testing data. This limitation in data prevented us from dividing patients into subgroups based on the pathomechanism. Also, the core laboratory did not evaluate the results of coronary angiographies, which were assessed at individual hospitals. What is more, we have excluded patients with cardiogenic shock and pulmonary edema in our study34. Finally, the National Health Fund was the sole provider of follow-up data, so the exact causes of death in the studied population were not available.

Conclusions

This large-scale registry-based analysis demonstrated higher 3 years crude rates of adverse events including death and MI among male patients. Furthermore, male sex was found to be one of independent risk factors of 3 years mortality and MI in multivariate analysis. Also, our study showed higher rate of cardiovascular readmissions in male population up to 3 years follow-up.

Data availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

Thygesen, K. et al. Fourth Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction (2018). Circulation 138(20), e618–e651. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000617 (2018). Erratum in: Circulation. 2018;138(20):e652. PMID: 30571511.

Barr, P. R. et al. Myocardial infarction without obstructive coronary artery disease is not a Benign Condition (ANZACS-QI 10). Heart Lung Circ. 27(2), 165–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hlc.2017.02.023 (2018).

Safdar, B. et al. Presentation, Clinical Profile, and prognosis of young patients with myocardial infarction with nonobstructive coronary arteries (MINOCA): results from the VIRGO Study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 7(13), e009174. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.118.009174 (2018). PMID: 29954744; PMCID: PMC6064896.

Pasupathy, S., Air, T., Dreyer, R. P., Tavella, R. & Beltrame, J. F. Systematic review of patients presenting with suspected myocardial infarction and nonobstructive coronary arteries. Circulation. ;131(10):861 – 70. (2015). https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.011201. Epub 2015 Jan 13. Erratum in: Circulation. 2015;131(19):e475. PMID: 25587100.

Parwani, P. et al. Contemporary diagnosis and management of patients with MINOCA. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 25(6), 561–570. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11886-023-01874-x (2023).

Scalone, G., Niccoli, G. & Crea, F. (eds) ‘s Choice- Pathophysiology, diagnosis and management of MINOCA: an update. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care 8(1):54–62. doi: 10.1177/2048872618782414. Epub 2018 Jun 28. PMID: 29952633. (2019).

Canton, L. et al. Sex- and age-related differences in outcomes of patients with acute myocardial infarction: MINOCA vs. MIOCA. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care 12(9):604–614. https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjacc/zuad059 (2023).

Gao, S., Ma, W., Huang, S., Lin, X. & Yu, M. Sex-specific clinical characteristics and long-term outcomes in patients with myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary arteries. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 8, 670401. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2021.670401 (2021).

Hawranek, M. et al. Renal function on admission affects both treatment strategy and long-term outcomes of patients with myocardial infarction (from the Polish Registry of Acute Coronary syndromes). Kardiol Pol. 75(4), 332–343. https://doi.org/10.5603/KP.a2017.0013 (2017).

Roleder, T. et al. Trends in diagnosis and treatment of aortic stenosis in the years 2006–2016 according to the SILCARD registry. Pol Arch Intern Med. ;128(12):739–745. https://doi.org/10.20452/pamw.4352 (2018).

Faryan, M. et al. Temporal trends in the availability and efficacy of catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter in a highly populated urban area. Kardiol Pol. 78(6), 537–544 (2020).

Niedziela, J. T. et al. Secular trends in first-time hospitalization for heart failure with following one-year readmission and mortality rates in the 3.8 million adult population of Silesia, Poland between 2010 and 2016. The SILCARD database. Int J Cardiol. ;271:146–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.05.015 (2018).

Ozierański, K. et al. Smoking ban in public places and myocardial infarction hospitalizations in a European country with high cardiovascular risk: insights from the Polish nationwide AMI-PL database. Pol. Arch. Intern. Med. 129 (6), 386–391. https://doi.org/10.20452/pamw.14862 (2019).

Yildiz, M. et al. Myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary arteries (MINOCA). Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 9, 1032436. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2022.1032436 (2022).

Pasupathy, S. et al. Survival in patients with suspected myocardial infarction with nonobstructive coronary arteries: a comprehensive systematic review and Meta-analysis from the MINOCA Global collaboration. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes. 14 (11), e007880 (2021). Epub 2021 Nov 16. PMID: 34784229.

Smilowitz, N. R. et al. Mortality of Myocardial Infarction by Sex, Age, and Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease Status in the ACTION Registry-GWTG (Acute Coronary Treatment and Intervention Outcomes Network Registry-Get With the Guidelines). Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 10(12):e003443. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.116.003443 (2017).

Gasior, P. et al. el al. Clinical Characteristics, Treatments, and Outcomes of Patients with Myocardial Infarction with Non-Obstructive Coronary Arteries (MINOCA): Results from a Multicenter National Registry. J Clin Med. ;9(9):2779. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9092779 (2020).

Alkhawam, H. et al. Myocardial infarct size and sex-related angiographic differences in myocardial infarction in nonobstructive coronary artery disease. Coron Artery Dis. 32(7):603–609. https://doi.org/10.1097/MCA.0000000000001018 (2021).

Jung, R. G. et al. Clinical features, sex differences and outcomes of myocardial infarction with nonobstructive coronary arteries: a registry analysis. Coron Artery Dis. ;32(1):10–16. https://doi.org/10.1097/MCA.0000000000000903 (2021).

Eggers, K. M. et al. Morbidity and cause-specific mortality in first-time myocardial infarction with nonobstructive coronary arteries. J. Intern. Med. 285 (4), 419–428. https://doi.org/10.1111/joim.12857 (2019). Epub 2018 Nov 25. PMID: 30474313.

Biondi-Zoccai, G. G. et al. Reduced post-infarction myocardial apoptosis in women: a clue to their different clinical course? Heart. ;91(1):99–101. (2005). https://doi.org/10.1136/hrt.2003.018754. Erratum in: Heart. 2005;91(3):370. PMID: 15604350; PMCID: PMC1768665.

De Filippo, O. et al. Impact of secondary prevention medical therapies on outcomes of patients suffering from myocardial infarction with NonObstructive Coronary artery disease (MINOCA): a meta-analysis. Int. J. Cardiol. 368, 1–9 (2022).

Choo, E. H. et al. KAMIR-NIH investigators. Prognosis and predictors of mortality in patients suffering myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary arteries. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 8(14), e011990 (2019).

Lindahl, B. et al. Medical therapy for secondary Prevention and Long-Term Outcome in patients with myocardial infarction with nonobstructive coronary artery disease. Circulation 135(16), 1481–1489 (2017).

Paolisso, P. et al. Secondary Prevention Medical Therapy and outcomes in patients with myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary artery disease. Front. Pharmacol. 10, 1606. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2019.01606 (2020).

Abdu, F. A. et al. Effect of Secondary Prevention Medication on the Prognosis in Patients With Myocardial Infarction With Nonobstructive Coronary Artery Disease. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 76(6):678–683. https://doi.org/10.1097/FJC.0000000000000918 (2020).

Ciliberti, G. et al. Characteristics of patients with recurrent acute myocardial infarction after MINOCA. Prog Cardiovasc. Dis. 2023 Nov-Dec 81: 42–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcad.2023.10.006. Epub 2023 Oct 16. PMID: 37852517.

Nordenskjöld, A. M. et al. Reinfarction in patients with myocardial infarction with nonobstructive coronary arteries (MINOCA): coronary findings and prognosis. Am. J. Med. 132(3), 335–346 (2019).

Konst, R. E. et al. Prognostic Value of Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging in patients with a Working diagnosis of MINOCA-An Outcome Study with up to 10 years of Follow-Up. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 16(8), e014454. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.122.014454 (2023).

Bergamaschi, L. et al. Prognostic role of early cardiac magnetic resonance in myocardial infarction with nonobstructive coronary arteries. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 17(2), 149–161 (2024).

Mileva, N. et al. Diagnostic and Prognostic Role of Cardiac Magnetic Resonance in MINOCA: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. ;16(3):376–389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcmg.2022.12.029 (2023).

Corbalan, R. et al. GARFIELD-AF investigators. Analysis of outcomes in ischemic vs nonischemic cardiomyopathy in patients with Atrial Fibrillation: a Report from the GARFIELD-AF Registry. JAMA Cardiol. 4 (6), 526–548. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2018.4729 (2019).

Ng, A. C., Sindone, A. P., Wong, H. S. & Freedman, S. B. Differences in management and outcome of ischemic and non-ischemic cardiomyopathy. Int. J. Cardiol. 129 (2), 198–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.07.014 (2008).

Armillotta, M. et al. Predictive value of Killip classification in MINOCA patients. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 117, 57–65 (2023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.M., M.K.,P.G. wrote the main manuscript text. M.B, J.F completed data collection. A.D. performed statistical analysis. M.M. Prepared Figs. 1, 2 and 3. M.G., K.M., K.W., Z.K., P.B., J.P.,M.M., W.W. checked the data and statistical results. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Milewski, M., Desperak, A., Koźlik, M. et al. Sex differences in patients with working diagnosis of myocardial infarction with nonobstructive coronary arteries (MINOCA). Sci Rep 15, 2764 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87121-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87121-5