Abstract

At present, the relationship between the intake of antioxidants in food and the mortality rate of patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD), especially the association with the mortality rate of specific causes, is not clear. This study included 6379 adult CKD patients from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (2001–2018). Use the Cox proportional hazards model, restricted cubic spline (RCS) model, and stratified and sensitivity analysis to evaluate the relationship between the Composite Dietary Antioxidant Index (CDAI) and mortality in patients with chronic kidney disease. During the follow-up period, 2381 all-cause deaths were recorded, including 719 deaths from cardiovascular disease, 132 deaths from cerebrovascular disease, and 430 deaths from cancer. We found that compared to the lowest quartile of CDAI, the weighted multivariate hazard ratio of participants in the highest quartile was 0.83 (95% confidence interval: 0.72, 0.96) for all-cause mortality, Cardiovascular mortality was 0.91 (95% confidence interval: 0.70, 1.18), Cerebrovascular death was 0.51 (95% confidence interval: 0.24, 1.07), Death due to cancer was 0.64 (95% confidence interval: 0.45, 0.92). RCS analysis shows a non-linear relationship between CDAI and all-cause mortality and cancer mortality. At the same time, there is no non-linear relationship between CDAI and cardiovascular mortality and cerebrovascular mortality. Stratified analysis shows that race and BMI are influencing factors for CDAI-CKD mortality. Sensitivity analysis confirmed the robustness of the results. Our research findings emphasize the potential advantages of an antioxidant diet in reducing the risk of mortality in CKD patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a progressive disease with structural or functional abnormalities of the kidneys due to a variety of causes, characterized by a sustained increase in protein excretion in the urine1. CKD affects 697 million people globally and causes 1.2 million deaths annually. Unfortunately, these numbers are increasing2, and by 2040, CKD will be the fifth leading cause of death worldwide3. It is important to note that cardiovascular causes are the leading cause of death in CKD patients4.

Studies have shown that the progression of CKD is associated with endothelial dysfunction, chronic hypoxia, tissue pathological damage, and specific molecular mechanisms5,6,7. Notably, oxidative stress is a significant mechanism in the progression of CKD and is a target for treatment8,9,10. Improving the nutritional status of CKD patients can aid in managing the disease11. Certain foods and nutrients have been scientifically proven to possess antioxidant properties, which can be beneficial in treating CKD. The Composite Dietary Antioxidant Index (CDAI) is a robust nutritional index calculated based on an individual’s intake of dietary antioxidants, including zinc, selenium, vitamin A, vitamin C, vitamin E, and carotenoids12,13. Related studies have shown that a higher CDAI is strongly associated with lower all-cause and cardiovascular mortality rates14, and the increase of CDAI is associated with a reduced risk of CKD15. However, the relationship between CDAI and the mortality risk of CKD patients, especially the specific mortality rates of various etiologies, is still uncertain.

Therefore, this study aims to investigate the correlation between CDAI and all-cause mortality, cancer-related mortality, cardiovascular mortality, and cerebrovascular mortality rates in adult CKD patients in the United States, using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). The study will also determine the most effective CDAI values, which can be a reference for antioxidant supplementation in CKD patients.

Materials and methods

Data and study population

The NHANES, conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, is a complex, ongoing, cross-sectional survey that uses probability sampling to assess the health and nutritional status of adults and children in the United States. This survey takes place every two years. The NHANES protocol was granted approval by the Institutional Review Board at the National Center for Health Statistics, and all participants in the NHANES provided informed consent. All data are publicly available at www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/16.

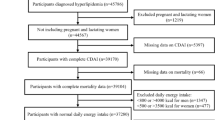

For our study, we utilized data from participants across nine NHANES cycles, spanning 2001 to 2018, with 91,351 participants. Participants were excluded if they were under 18 (n = 37,595), had no CKD (n = 44,811), lacked mortality data (n = 9), lacked CDAI data (n = 673), or lacked covariate data (n = 1,884). Consequently, 6,379 patients with CKD were included in the analysis, the process of inclusion and exclusion is shown in Fig. 1. The National Center approved the NHANES for Health Statistics Ethics Review Board, and all participants provided written informed consent.

Diagnostic CKD

CKD was defined based on the 2012 Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes recommendations, the presence of either a low estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) or albuminuria was considered a diagnostic of CKD17. eGFR was calculated using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration study formula based on serum creatinine levels18. An eGFR of less than 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 was considered low. Albuminuria is a urine albumin creatine ratio of 30 mg/g or higher. The Jaffe rate method (kinetic alkaline picrate) was used to determine creatinine concentration in serum. Urinary albumin was measured by solid-phase fluorescent immunoassay19, and urinary creatinine was measured by enzymatic method.

Calculate of composite dietary antioxidant index

NHANES’s dietary interview component, “What We Eat in America (WWEIA),” assesses food and nutrient intake, and the US Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrient Database for Dietary Studies provides the nutrient composition of the foods included in this component. During the survey, all participants underwent two 24-hour dietary recalls. The first day’s recall is collected at the Mobile Examination Center, and the second day’s recall is collected by phone 3 to 10 days later. Our study used data from the first dietary recall, calculating the CDAI according to established methods13,14. In brief, the six dietary antioxidants (zinc, selenium, vitamin A, vitamin C, vitamin E, and carotenoids) are standardized by subtracting the sex-specific mean and dividing it by the sex-specific standard deviation. CDAI is then calculated using the sum of these standardized dietary antioxidant intakes, as outlined below:

Other covariates

Covariate data included demographic information (age, gender, race, education, marital status, ratio of family income to poverty(PIR)), comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and heart disease), smoking and alcohol use status, Body Mass Index (BMI), physical activity, and energy intake.

The diagnosis of hypertension was based on the question from the questionnaire, “Ever told you had high blood pressure?” The diagnosis of diabetes mellitus (DM) had six reference criteria: glycosylated hemoglobin, type A1C > 6.5%, fasting glucose ≥ 7.0 mmol/L, random blood glucose ≥ 11.1 mmol/L, oral glucose tolerance test 2 h blood glucose ≥ 11.1 mmol/L, use of diabetes medication or insulin, and being told by a doctor of diabetes, meeting any of these criteria was considered indicative of DM. Diagnosis of hyperlipidemia had three criteria: triglyceride ≥ 150 mg/dL; total cholesterol ≥ 5.18 mmol/L, low-density lipoprotein ≥ 3.37 mmol/L, or high-density lipoprotein < 1.04 mmol/L for males and < 1.30 mmol/L for females; or using lipid-lowering drugs, meeting any of these was considered indicative of hyperlipidemia. Responses to four questions determined cardiovascular disease (CVD): “Ever told had congestive heart failure?”, “Ever told you had coronary heart disease?”, “Ever told you had angina/angina pectoris?” and “Ever told you had a heart attack”, a “Yes” response to any of these questions indicated CVD. Smoking status was classified into three levels: never smoked (smoked less than 100 cigarettes in life), previously smoked (smoked more than 100 cigarettes in life and do not smoke now), and current smokers (smoked more than 100 cigarettes in life and smoked some days or every day). Five levels of alcohol use were identified: never (had < 12 drinks in a lifetime), former (had ≥ 12 drinks in 1 year and did not drink last year, or did not drink previous year but drank ≥ 12 drinks in a lifetime), moderate (≥ two drinks per day for women or ≥ three drinks per day for men, or binge drinking ≥ 2 & <5 days per month), heavy (≥ three drinks per day for women or ≥ 4 drinks per day for men, or binge drinking ≥ 5 days per month), and mild (not meeting the above criteria). The BMI has three levels: normal (BMI < 25 kg/m²), overweight (25 ≤ BMI < 30 kg/m²), and obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m²). For physical activity assessment, we used “recreational activity” (before 2006) and “muscle strength” (after 2007) from NHANES, standardizing the data, “unable to do activity” was categorized as no (before 2006), while “vigorous” “moderate” and “both” were classified as yes (after 2007), ultimately determining physical activity as yes or no. Energy intake data from the first dietary recall is in the Total Nutrient Intake folder.

Mortality assessment

The mortality status, timing, and cause of death of the participants were ascertained using the public access files of the National Death Index up until December 31, 2019. Causes of death were defined using the International Classification of Diseases, tenth version (ICD-10) codes, such as diseases of the heart (ICD-10 codes I00-I09, I11, I13, I20-I51), malignant neoplasms (ICD-10 codes C00-C97), nephritis, nephrotic syndrome, and nephrosis (ICD-10 codes N00-N07, N17-N19, N25-N27), among others. Survival time was measured from the examination date at the Mobile Examination Center to the outcome date. Our research focuses primarily on mortality rates and the various causes of death.

Statistical analysis

In accordance with NHANES analysis guidelines20, all analyses were performed after integrating sample dietary weights. We divided all participants into four groups based on CDAI quartiles. For general population characteristics, continuous variables were described by mean ± standard error (SE), and categorical variables were described by the number of individuals (percentage). The χ2 test (for categorical variables) and generalised linear regression models (for continuous variables) were used to assess differences in baseline characteristics between the four groups.

The proportional hazards assumption was tested using scaled Schoenfeld residuals, and the results indicated that none of the covariates had statistical significance, nor did the global test. Therefore, we chose the Cox proportional hazards regression model to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of CDAI with all-cause mortality, cancer-related mortality, cardiovascular mortality, and cerebrovascular mortality. Adjustments were made for confounding factors that may affect the research results, which were selected based on the association between dietary intake and mortality and the literature on CKD mortality. Model 1, the crude model, which was non-adjusted. Model 2, which was adjusted for age. Model 3, which was further adjusted (from Model 2) for gender, race/ethnicity. Model 4, which was further adjusted (from Model 3) for marital status, education, BMI, PIR, hypertension, DM, hyperlipidemia, cardiovascular disease.

We also used restricted cubic splines (RCS) with five knots at the 5th, 35th, 50th, 65th, and 95th centiles to flexibly model the association of CDAI with mortality, adjusting for confounders. We used slope method to assess the fitted curve’s slope to determine the inflection point’s value in the case of a non-linear relationship. Threshold effect analysis was then performed on either side of the inflection point using a segmented COX proportional hazards model to test the association between CDAI and mortality further.

Stratified analyses included age (≤ 60 or > 60 years), gender, race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white or other), BMI (< 30.00 or ≥ 30.00), smoking status (current, past, or never), hypertension (yes or no), and DM (DM, impaired fasting glucose (IFG), impaired glucose tolerance (IGT), or no). Several sensitivity analyses were also performed, including (1) excluding those with DM, (2) excluding participants who died within the first two years of follow-up, and (3) further adjusting for C-reactive protein in the model, (4) The systemic immunity inflation index (SII) and physical activity in the model were further adjusted.

All statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.0.5, and a P < 0.05 (two-tailed) was considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline population characteristics

The final sample consisted of 6,379 CKD participants, representing 2.542 million CKD patients in the United States. Table 1 shows the weighted baseline characteristics of the participants stratified by CDAI quartiles. The mean age was 60.72 ± 0.33 years; 43.43% were male, and 71.94% were identified as non-Hispanic white. The mean CDAI ± SE was 0.22 ± 0.07. Participants with a higher CDAI were more likely to be younger, non-Hispanic white, married, more educated, less physically active, have a higher PIR, and suffer from hypertension, DM, and CVD. They were also less likely to be current smokers and non-drinkers. In addition, Supplementary Table S1 shows that compared to survivors, the deceased consumed less vitamin E, selenium, and carotenoids in their diet, and the difference was statistically significant. Additionally, the deceased consumed slightly more vitamin A and less zinc and vitamin C, but the difference was insignificant.

Relationships between CDAI and mortality

As of 31 December 2019, the median follow-up was 84 months (ranging from 0 to 228 months), with a total of 2,381 deaths, representing an all-cause mortality rate of 37.33%. These deaths included 719 deaths from CVD, 132 deaths from cerebrovascular disease, and 430 deaths from cancer. The results of COX regression analysis are shown in Table 2. In the unadjusted model, CDAI showed a significant negative correlation with all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, and cancer mortality in CKD patients, with a dose-response relationship. However, the correlation between CDAI and cerebrovascular mortality was inconsistent among the four groups. In both partially and fully adjusted models, there was a sustained significant negative correlation between CDAI and all-cause mortality and cancer mortality in CKD patients. However, no such association was observed with cardiovascular mortality. After adjusting Model 4, compared to the lowest quartile of CDAI, the multivariable HRs and 95% CIs for all-cause mortality were 0.92 (0.80, 1.06) for Q2, 0.91 (0.79, 1.04) for Q3, and 0.83 (0.72, 0.96) for Q4 (P for trend = 0.02); for cardiovascular mortality were 0.85 (0.64, 1.12) for Q2, 0.87 (0.68, 1.11) for Q3, and 0.91 (0.70, 1.18) for Q4 (P for trend = 0.63); for cerebrovascular mortality were 1.02 (0.59, 1.78) for Q2, 1.13 (0.60, 2.13) for Q3, and 0.51 (0.24, 1.07) for Q4 (P for trend = 0.07); for cancer mortality were 0.80 (0.58, 1.12) for Q2, 0.77 (0.55, 1.09) for Q3, and 0.64 (0.45, 0.92) for Q4 (P for trend = 0.02). For CKD patients, higher CDAI is significantly associated with a lower risk of all-cause mortality and cancer mortality. At the same time, there is no independent correlation between CDAI and cardiovascular mortality and cerebrovascular mortality.

The detection of nonlinear relationships

We use RCS curves to explore the potential nonlinear relationship between CDAI and all-cause and specific-cause mortality in CKD patients. The results showed that there was an L-shaped relationship (nonlinear P = 0.032) between CDAI level and all-cause mortality rate (Fig. 2A) and a J-shaped relationship (nonlinear P = 0.002) between CDAI level and cancer-related mortality rate (Fig. 2B). In addition, no nonlinear correlation was found between CDAI and CVD-related mortality (Fig. 2C) and brain-related mortality (Fig. 2D).

Association between CDAI and all-cause (A), cancer mortality (B), CVD mortality (C) and brain mortality (D) in patients with CKD. Adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, education, BMI, ratio of family income to poverty, hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, CVD. CDAI composite dietary antioxidant index, CVD cardiovascular disease, CKD chronic kidney disease, BMI body mass index.

Stratified and sensitivity analyses

We conducted stratified analyses based on age (≤ 60 or > 60 years), gender (male or female), race (non-Hispanic white or other), BMI (< 30 or ≥ 30 kg/m²), smoking status (past, current, or never), history of hypertension (yes or no), and history of diabetes mellitus (DM, no, IFG, or IGT). The results are shown in Fig. 3, for all-cause mortality, there is a significant interaction between CDAI and the race and BMI of CKD patients, a significant negative correlation was observed in non-Hispanic white persons and those with BMI < 30 kg/m²; for cancer-specific mortality, no interaction was observed between CDAI and stratified variables. In addition, race stratification was significant in CVD mortality (Supplementary Table S2), while BMI and DM stratifications were significant in cerebrovascular-cause mortality (Supplementary Table S3).

Forest plots of stratified analyses of CDAI with all-cause mortality and cancer mortality in CKD. Age, sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, education, body mass index, ratio of family income to poverty, hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia and cardiovascular disease were adjusted except the variable itself. HR hazard ratio, CI confidence interval, CDAI composite dietary antioxidant index, CKD chronic kidney disease, BMI body mass index, DM diabetes, IFG impaired fasting glucose, IGT impaired glucose tolerance.

We further conducted a sensitivity analysis, and the results are shown in Supplementary Tables S4-S7. For patients with a history of DM and those who died within 2 years before follow-up, CRP was further adjusted based on Model 4, and SII and physical activity were further adjusted based on Model 4. The results showed that the relationship between CDAI and all-cause, cancer, cardiovascular disease, and cerebrovascular disease mortality in CKD patients was consistent with the findings of Cox regression analysis.

Discussion

This study analyzed the relationship between CDAI and mortality risk in adult CKD patients based on the NHANES database. We found a negative correlation between all-cause mortality and cancer-related mortality between CDAI and CKD; even after adjusting multiple models for multiple variables, this significant negative correlation still exists. In further non-linear testing, we found a non-linear relationship between CDAI and the all-cause mortality rate and cancer-related mortality rate of CKD. There was an L-shaped relationship between CDAI and all-cause mortality rate and a J-shaped relationship between CDAI and cancer-related mortality rate. As CDAI increased, the mortality rate of CKD patients showed a downward trend until it no longer decreased after a certain threshold. Although cardiovascular mortality showed a significant negative correlation with CDAI, this relationship did not exist after multivariate adjustment. For mortality caused by cerebrovascular diseases, there was a positive correlation in the Q2 and Q3 groups of CDAI and a negative correlation in the Q4 group. After adjusting for multiple variables, this relationship was not statistically significant. The above research suggests that within a specific range, higher CDAI is significantly associated with lower all-cause mortality and cancer-related mortality in CKD. In contrast, the CDAI and cardiovascular and cerebrovascular mortality relationship is not yet precise. The study also found that the intake of antioxidants, especially CDAI, vitamin E, selenium, and carotenoids, may reduce the mortality rate of CKD patients. These results emphasize the importance of increasing the intake of antioxidant-rich foods in the diet of CKD patients to reduce mortality and improve prognosis.

In CKD, oxidative stress increases as the disease progresses21. This results from an imbalance between excessive oxidant production and insufficient antioxidants, leading to tissue damage22. Excess reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the body participate in various pathological processes and cause damage to cells and tissues23. Antioxidants inhibit the formation of ROS, directly eliminate ROS and repair damage caused by ROS. People can obtain exogenous antioxidants from their diet. The elevation of ROS levels plays an important role in tumor development, and targeting ROS to regulate redox is considered a promising treatment strategy for cancer24. Besides oxidative stress, cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases are influenced by various factors, including metabolic, lifestyle, and genetic factors. This may be the reason why CDAI has a more robust impact on cancer-related mortality rates than on cardiovascular and cerebrovascular mortality rates.

Previous studies have examined the relationship between nutrients and antioxidant properties in the diet and CKD, but the results must be consistent. A cross-sectional study showed that plasma levels of manganese, iron, and zinc correlate negatively with CKD, while selenium levels do not25. A prospective study indicated that serum selenium protein concentration is positively associated with impaired kidney function26,27,28. Other studies have shown that adequate intake of selenium negatively correlates with the prevalence and progression of CKD29,30,31. Regarding carotenoids, long-term insufficient intake, compared to adequate intake, is associated with a higher prevalence of CKD32, with gender differences observed33. A study based on NHANES data showed that high levels of dietary or serum carotenoids are associated with a reduced risk of death in CKD34. Supplementing vitamins C and E can effectively alleviate oxidative stress and inflammation levels caused by hemodialysis35,36. Dietary vitamin E intake negatively correlates with the prevalence of CKD in American adults37. However, the intake of nutrients in the diet is not singular, and assessing the daily intake of antioxidants remains a challenge for clinical doctors. CDAI is calculated based on the content of six antioxidants in the diet, which can comprehensively evaluate the comprehensive anti-inflammatory effects of antioxidants in the diet. Existing studies suggest that CDAI can reduce mortality in the general population and patients with diabetic kidney disease14,38, higher CDAI is associated with a lower risk of all-cause mortality in CKD1-2 patients39. Based on previous research and our findings, dietary antioxidants, especially vitamin E, selenium, and carotenoids, have an advantage in reducing mortality in CKD patients. CDAI can evaluate the overall intake of antioxidants in patients and may serve as a biomarker for predicting CKD prognosis. However, the calculation of CDAI is relatively complex for clinical doctors, as it requires recording the daily diet of patients, calculating the amount of each antioxidant contained in it, and combining it with the calculation formula. Therefore, it is currently more widely used in scientific research.

We performed stratified analyses to eliminate the impact of confounding factors on the results. We observed significant interactions of CDAI with all-cause mortality rates in terms of race and BMI, particularly a significant negative correlation in non-Hispanic white and those with a BMI < 30 kg/m². Higher CDAI also showed more advantages in reducing mortality rates in men, non-smokers, those with hypertension, and those without DM, although the interactions were not significant. Previous studies have shown that the intake of related antioxidant nutrients in the diet of people with normal weight is significantly higher than that of obese individuals40. In the United States, the proportion of Black people with kidney failure is much higher than that of White people41. Our results are broadly consistent with previous studies. Therefore, when managing the diet of CKD patients, it is necessary to consider the appropriate combination of antioxidant foods, especially in non-Hispanic white persons and those with a BMI < 30 kg/m².

There are several limitations to this study. First, this is an observational cross-sectional study. Participants are based on the United States population data, but other countries’ population data are not included. The cross-sectional study design may affect the interpretation of the relationship between CDAI and mortality of CKD patients and the inference of the causal relationship. Although it is observed that there is a significant nonlinear relationship between CDAI and mortality of CKD patients from all causes and cancer causes, the causal relationship cannot be determined. Secondly, CDAI data obtained through 24-hour dietary recall may have biases and may not reflect the effects of long-term dietary patterns. However, we selected the initial dietary data of all participants to ensure that all dietary data were obtained under the same conditions to minimize errors to the greatest extent possible. Thirdly, although the influence of weights was considered in the analysis and regression models, stratified and sensitivity analyses were used to control for some confounding factors. However, residual confounding factors from difficult-to-determine or unknown variables may persist. In the future, more in-depth clinical and basic research is needed to determine whether the benefits of antioxidants in the diet for CKD patients persist in the long term and to establish causal relationships.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates a significant association between a higher CDAI and lower all-cause and cancer-specific mortality rates in adults with CKD. The relationship between CDAI levels and mortality rates is non-linear, with an L-shaped for all-cause mortality and a J-shaped for cancer-specific mortality. These findings suggest that nutrients with antioxidant properties may potentially impact the mortality rates of CKD patients.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed in the current study are available at NHANES website: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CDAI:

-

Composite dietary antioxidant index

- CKD:

-

Chronic kidney disease

- DM:

-

Diabetes

- eGFR:

-

Estimated glomerular filtration rate

- IFG:

-

Impaired fasting glucose

- IGT:

-

Impaired glucose tolerance

- NHANES:

-

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- PIR:

-

Poverty income ratio

- SE:

-

Standard error

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

References

K/DOQI clinical. Practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Am. J. Kidney Dis.: Offi. J. Natl. Kidney Found. 39(2 Suppl 1), S1-266 (2002).

Global, regional, and national burden of chronic kidney disease, 1990-2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet (London, England) 395(10225), 709–33 (2020).

Foreman, K. J. et al. Forecasting life expectancy, years of life lost, and all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 250 causes of death: Reference and alternative scenarios for 2016-40 for 195 countries and territories. Lancet (London England) 392 (10159), 2052–2090 (2018).

Thomas, B. et al. Global Cardiovascular and renal outcomes of reduced GFR. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol.: JASN 28 (7), 2167–2179 (2017).

Dong, Y. et al. Advances in the detection, mechanism and therapy of chronic kidney disease. Curr. Pharm. Des. 25 (40), 4235–4250 (2019).

Fine, L. G. & Norman, J. T. Chronic hypoxia as a mechanism of progression of chronic kidney diseases: From hypothesis to novel therapeutics. Kidney Int. 74 (7), 867–872 (2008).

Wang, C. et al. The role and mechanism of RIPK1 in vascular endothelial dysfunction in chronic kidney disease. FASEB J.: Off. Publ. Fed. Am. Soc. Exp. Biol. 38 (2), e23446 (2024).

Small, D. M., Coombes, J. S., Bennett, N., Johnson, D. W. & Gobe, G. C. Oxidative stress, anti-oxidant therapies and chronic kidney disease. Nephrol. (Carlton Vic) 17 (4), 311–321 (2012).

Cachofeiro, V. et al. Oxidative stress and inflammation, a link between chronic kidney disease and cardiovascular disease. Kidney Int. Supplement 74(111), S4–S9 (2008).

Annuk, M., Zilmer, M., Lind, L., Linde, T. & Fellström, B. Oxidative stress and endothelial function in chronic renal failure. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol.: JASN 12 (12), 2747–2752 (2001).

MacLaughlin, H. L., Friedman, A. N. & Ikizler, T. A. Nutrition in kidney disease: Core Curriculum 2022. Am. J. Kidney Dis.: Off. J. Natl. Kidney Found. 79 (3), 437–449 (2022).

Wright, M. E. et al. Development of a comprehensive dietary antioxidant index and application to lung cancer risk in a cohort of male smokers. Am. J. Epidemiol. 160 (1), 68–76 (2004).

Maugeri, A. et al. Dietary antioxidant intake decreases carotid intima media thickness in women but not in men: a cross-sectional assessment in the Kardiovize study. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 131, 274–281 (2019).

Wang, L. & Yi, Z. Association of the composite dietary antioxidant index with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality: A prospective cohort study. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 9, 993930 (2022).

Wang, M., Huang, Z-H., Zhu, Y-H., He, P. & Fan, Q-L. Association between the composite dietary antioxidant index and chronic kidney disease: Evidence from NHANES 2011–2018. Food Funct. 14 (20), 9279–9286 (2023).

Cetners for disease control and prevention. about the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. NHANES. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm

Chapter 1. Definition and classification of CKD. Kidney Int. Suppl. 3 (1), 19–62 (2013).

Levey, A. S., Levin, A. & Kellum, J. A. Definition and classification of kidney diseases. Am. J. Kidney Dis.: Off. J. Natl. Kidney Found. 61 (5), 686–688 (2013).

Chavers, B. M., Simonson, J. & Michael, A. F. A solid phase fluorescent immunoassay for the measurement of human urinary albumin. Kidney Int. 25 (3), 576–578 (1984).

NHANES Tutorials. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/tutorials/default. aspx.

Dounousi, E. et al. Oxidative stress is progressively enhanced with advancing stages of CKD. Am. J. Kidney Dis.: Off. J. Natl. Kidney Found. 48 (5), 752–760 (2006).

Sies, H. Oxidative stress: Oxidants and antioxidants. Exp. Physiol. 82 (2), 291–295 (1997).

Kishi, S., Nagasu, H., Kidokoro, K. & Kashihara, N. Oxidative stress and the role of redox signalling in chronic kidney disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 20 (2), 101–119 (2024).

Glorieux, C., Liu, S., Trachootham, D. & Huang, P. Targeting ROS in cancer: Rationale and strategies. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 23 (8), 583–606 (2024).

Shen, Y. et al. Plasma element levels and risk of chronic kidney disease in elderly populations (≥ 90 years old). Chemosphere 254, 126809 (2020).

Reinhardt, W. et al. Chronic kidney disease distinctly affects relationship between selenoprotein P status and serum thyroid hormone parameters. Thyroid: Off. J. Am. Thyroid Assoc. 25 (10), 1091–1096 (2015).

Park, S. et al. Genetically predicted body selenium concentration and estimated GFR: A mendelian randomization study. Kidney Int. Rep. 8 (4), 851–859 (2023).

Fu, S. et al. Effects of Selenium on chronic kidney disease: A mendelian randomization study. Nutrients 14, 21 (2022).

Xie, C. et al. Association between selenium status and chronic kidney disease in middle-aged and older Chinese based on CHNS Data. Nutrients 14(13), 2695 (2022).

Liang, J-H. et al. Synergistic impact of co-exposures to whole blood metals on chronic kidney disease in general US adults: A cross–sectional study of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2011–2020. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. Int. 30 (53), 113948–113961 (2023).

Li, Y. et al. Inverse association between baseline plasma selenium concentrations and risks of renal function decline in hypertensive adults. J. Nutr. 152 (12), 2754–2760 (2023).

Suarez, J. J. et al. Food access, chronic kidney disease, and hypertension in the U.S. Am. J. Prev. Med. 49 (6), 912–920 (2015).

Shi, Y., Xu, Y. & Zhou, W. Dietary carotenoids intake and sex differences in relation to chronic kidney disease a cross-sectional assessment in the NHANES study. BMC Public. Health 24 (1), 293 (2024).

Hu, Y. et al. Relation between dietary carotenoid intake, serum concentration, and mortality Risk of CKD patients among US adults: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2001–2014. Front. Med. 9, 871767 (2022).

Yang, C. C., Hsu, S. P., Wu, M. S., Hsu, S. M. & Chien, C. T. Effects of vitamin C infusion and vitamin E-coated membrane on hemodialysis-induced oxidative stress. Kidney Int. 69 (4), 706–714 (2006).

Supriyadi, R., Koswara, M. I. A., Soelaeman, M. A. & Huang, I. The effect of antioxidants supplementation on oxidative stress and proinflammatory biomarkers in patients with chronic kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 27 (4), 1413–1426 (2023).

Li, J., Liu, Z., Pu, Y., Dai, H. & Peng, F. Association between dietary vitamin E intake and chronic kidney disease events in US adults: A cross-sectional study from NHANES 2009–2016. Clin. Kidney J. 16 (12), 2559–2566 (2023).

Zhang, J. et al. Dose-response relationship between dietary antioxidant intake and diabetic kidney disease in the US adults with diabetes. Acta Diabetol. 60 (10), 1365–1375 (2023).

Li, Y. et al. Association of dietary total antioxidant capacity with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in patients with chronic kidney disease: Based on two retrospective cohort studies of NHANES. Ren. Fail. 45 (1), 2205950 (2023).

Vahid, F., Rahmani, D. & Davoodi, S. H. The correlation between serum inflammatory, antioxidant, glucose handling biomarkers, and dietary antioxidant index (DAI) and the role of DAI in obesity/overweight causation: Population-based case-control study. Int. J. Obes. 45(12), 2591–2599 (2021).

Dykes, K., Desale, S., Javaid, B., Miatlovich, K. & Kessler, C. A new reality for multiple myeloma renal failure: US data report on kidney transplant outcomes. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 22 (5), e314–e320 (2022).

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Zhang Jing (Second Department of Infectious Disease, Shanghai Fifth People’s Hospital, Fudan University) for his work on the NHANES database.

Funding

The National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82104840); Scientific and Technological Innovation Project of China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences (No. CI2021A01615); Youth Science and Technology Talent Training Special Project of Chinese Academy of Traditional Chinese Medicine (No. ZZ16-YQ-022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JS and YL: Conceptualization. JS, HY, AS and WX: Writing—original draft. HG, LH, YW, XZ, PX, XT and YL: Writing—review and editing. LH: Funding acquisition. JS: Software. JS: Investigation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sun, J., Yang, H., Sun, A. et al. Association of composite dietary antioxidant index with mortality risk among adults with chronic kidney disease in NHANES. Sci Rep 15, 2578 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87230-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87230-1