Abstract

The brown marmorated stink bug, Halyomorpha halys (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae), is an invasive pest causing major economic losses to crops. Since its outbreaks in North America and Europe, H. halys has been controlled with synthetic pesticides. More sustainable methods have been proposed, including biocontrol and use of natural products. Here, we conducted laboratory and field investigations to evaluate organically registered products for their effectiveness against H. halys and their non-target effect on the egg parasitoid, Trissolcus japonicus (Hymenoptera: Scelionidae). In the laboratory, azadirachtin, orange oil, potassium salts of fatty acids, kaolin, basalt dust, diatomaceous earth, zeolite, sulphur formulations, calcium polysulfide, and mixtures of sulphurs plus diatomaceous earth or zeolite demonstrated higher lethality against H. halys nymphs compared to control. Calcium polysulfide, azadirachtin and sulphur achieved more than 50% mortality. All treatments except azadirachtin and kaolin had negative effects on T. japonicus, with mortality exceeding 80% for calcium polysulfide and sulphur. Field experiments were conducted in 2021 and 2022 in pear orchards. Diatomaceous earth alone or alternated with sulphur or calcium polysulfide provided similar H. halys control, when compared to farm strategies based mostly on neonicotinoid (acetamiprid) treatments. Implications for H. halys control in integrated pest management are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The spread of invasive species is one of the most relevant biosecurity problems of recent years, and it is expected to increase over time1. The introduction of exotic plants, animals, pathogens or other organisms is often a result of accidental events caused by human activities, with globalisation further promoting their spread2,3. Depending on the species, biological invasions may pose a significant threat to agriculture, local biodiversity, human and animal health4,5. Many invasive species are herbivorous insects that damage agricultural crops6, and although integrated pest management promotes the use of both biological and chemical strategies for a more sustainable crop protection approach7,8, conventionally, the prevalent method used against invasive pests is the use of synthetic insecticides9,10,11. However, repeated applications of chemicals cause several side effects, as for example the development of resistance in target pests and the consequent reduction of pesticide efficacy12,13,14. Likewise, the extensive use of synthetic products has adverse effects on non-target organisms, human health, and the environment15,16. Therefore, products such as organophosphates and several neonicotinoids have been banned in Europe17,18,19. Meanwhile, more eco-friendly, natural, pesticides are being developed, and several products have proven as excellent alternatives to synthetic chemicals for pest control. These substances originate from various sources, and include natural dusts, essential oils20,21,22, and bioinsecticides derived from microorganisms23,24. For example, rock powder, a dust of natural origin allowed in organic agriculture, was shown to be effective in preventing and reducing the attack of the olive pest Bactrocera oleae (Rossi) (Diptera: Tephritidae)25,26. Bioinsecticides based on Beauveria bassiana were also highly effective in controlling the western flower thrips, Frankliniella occidentalis (Pergande) (Thysanoptera: Thripidae)27,28,29.

However, the natural origin of a pesticide does not necessarily correlate with its safety to non-target beneficial insects30,31,32,33. Though generally considered safer than synthetic insecticides, still natural insecticides may be associated to lethal and sublethal effects on predators and parasitoids34,35,36,37,38. These effects should not be overlooked, as both in organic farming and in integrated crop production a key element for managing invasive agricultural pests is biological control39,40. This includes classical biological control, which refers to the introduction and release of natural enemies, native from the same geographic area of the invasive pest41,42. Hence, when utilizing natural products in conjunction with biological control, it is crucial to assess their lethal effects on the introduced natural enemy.

Currently, one of the most important invasive herbivorous insects in the Northern Hemisphere is the brown marmorated stink bug Halyomorpha halys Stål (Heteroptera: Pentatomidae), native from Asia and distributed also in the American continent, Europe, and North Africa43,44,45. Being highly polyphagous, its host range in the native and invaded areas includes fruit trees, vegetables, horticultural crops, ornamental plants, and natural vegetation43,46. In Europe, H. halys was first found in Switzerland in 2004 and has since spread across the continent47. It was detected in Italy in 2012, causing severe damage to the agricultural sector48. The egg parasitoid Trissolcus japonicus (Ashmead) (Hymenoptera: Scelionidae) has been recognised as the main natural enemy of H. halys in its native area, and therefore it has been evaluated and released for classical biological control49,50,51.

The first aim of this research was to test in the laboratory the efficacy of different natural products for possible use as a farm strategy, alternative to synthetic pesticides, against H. halys. A second objective was to assess possible side effects of the same products on T. japonicus. All tested products are allowed in organic farming, as they are listed in the Regulation (EU) 2018/848 and Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2021/1165. Most of them (azadirachtin, orange oil, potassium salts of fatty acids, sulphurs, diatomaceous earth, and calcium polysulfide) are included and approved in the EU pesticide database (https://ec.europa.eu/food/plant/pesticides/eu-pesticides-db_en). Previous experiments on H. halys focused on the effects of entomopathogens52,53,54. Lethality effects of azadirachtin and potassium salts of fatty acids were also investigated against adults of H. halys, but showed contrasting effects when applied alone, in either direct application or contact assays55,56. A few investigations of non-target effects on T. japonicus explored the impact of natural products, such as spinosad and pyrethrins57,58,59. A third objective was to test the efficacy of promising products in reducing fruit damage in pear orchards over two consecutive seasons, with comparison to the current management strategies commonly adopted in each orchard, that were mostly based on acetamiprid applications. Considering the expected future limitation in the use of acetamiprid60 and the increased presence of egg parasitoids in field orchards, due to the ongoing biological control programme61, our results will help to implement pest management strategies with lower risks for biocontrol agents.

Results

Laboratory lethal effect assays on Halyomorpha halys

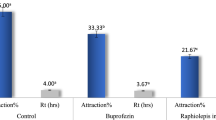

All tested products caused lethal effects on H. halys nymphs (Table 1). Concerning Experiment 1, the liquid insecticides azadirachtin, potassium salts of fatty acids, and orange oil were equally effective in causing mortality after 4 days from application, and their effects were significantly higher than control (Linear model; comparison of treatments: F(2,12) = 0.11, P = 0.89; treatments vs. control: t = 17.17, df = 1, P < 0.0001). Percentages increased after 7 days, and significant effects were confirmed (comparison of treatments: F(2,12) = 2.21, P = 0.15; treatments vs. control: t = 7.68, df = 1, P < 0.0001). Similar results were obtained in Experiment 2, when basalt dust, kaolin, diatomaceous earth, and zeolite were compared to each other and with the control, both at 4 days (comparison of treatments: F(3,16) = 1.68, P = 0.21; treatment vs. control: : t = 8.51, df = 1, P < 0.0001) and at 7 days from the treatment (comparison of treatments: F(3,16) = 0.69, P = 0.57; treatments vs. control: t = 9.71, df = 1, P < 0.0001). In Experiment 3, the efficacy of sulphur type 1 and type 2 at day 4 was similar, and when they were applied in mixture with zeolite or diatomaceous earth still no significant differences were observed, and they all caused higher mortality than control (comparison of treatments: F(4,20) = 1.63, P = 0.21; treatments vs. control: t = 7.05, df = 1, P < 0.0001). After 7 days overall efficacy increased, although with similar levels of significance (comparison of treatments: F(4,20) = 0.68, P = 0.61; treatments vs. control: t = 11.77, df = 1, P < 0.0001). In Experiment 4, the different doses of calcium polysulfide caused different levels of mortality, with the highest dose of 50 g/L being the most effective, the dose of 30 g/L showing an intermediate efficacy, and the lowest dose of 20 g/L being not different from the control (comparison of treatments: F(2,12) = 13.43, P = 0.0009; polysulfide 20 g/L vs. control: t = 0.57, df = 1, P = 0.58). At 7 days from the treatment, the overall efficacy of calcium polysulfide increased in all treatments, with the same trend among doses (comparison of treatments: F(2,12) = 12.41, P = 0.001) and the lowest dose of 20 g/L being not different from control (polysulfide 20 g/L vs. control: t = 2.11, df = 1, P = 0.056).

Laboratory lethal effect assays on Trissolcus japonicus

The tested products, except azadirachtin and kaolin, caused lethal effects also on the parasitoid, T. japonicus, but with highly variable percentages (Table 2). At 4 days from the treatment, calcium polysulfide had the highest effect among treatments, followed by sulphurs type 1 and type 2, zeolite, diatomaceous earth, potassium salts of fatty acids, and basalt dust (Linear model; comparison of treatments: F(9,30) = 3.86, P = 0.0025). Mortality caused by azadirachtin, kaolin, and orange oil did not differ from control (azadirachtin vs. control: t = 0.58, df = 1, P = 0.57; kaolin vs. control: t = 0.84, df = 1, P = 0.41; orange oil vs. control: t = 1.97, df = 1, P = 0.058). Overall, all mortality percentages increased at 7 days from the treatment, with calcium polysulfide and both sulphurs showing higher effects compared to all other products (comparison of treatments: F(9,30) = 8.16, P < 0.0001). Mortality caused by azadirachtin and kaolin did not differ from control (azadirachtin vs. control: t = 0.53, df = 1, P = 0.60; kaolin vs. control: t = 1.06, df = 1, P = 0.30).

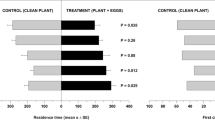

Field experiments and fruit injury evaluation

The experimental strategies tested in the pear orchards in 2021 and 2022 showed variable efficacy in controlling fruit damage by H. halys compared to the farm strategies. Fruit injury varied between orchards and years and increased in all plots as the season progressed, with significant differences between treatments, particularly at the third sampling date (Table 3).

In 2021, a comparison between organic strategies was designed in orchard A. Both experimental treatments, Akanthomyces muscarius Ve6 and B. bassiana GHA, provided better control of fruit injury compared to the farm strategy based on diatomaceous earth and to the untreated control. These differences were observed along the whole season, except that efficacy of diatomaceous earth vs. untreated control emerged slowly and was significant only at second and third sampling dates (Linear Models; 29/06/2021: F(3,12) = 7.10, P = 0.0053; 20/07/2021: F(3,12) = 37.18, P < 0.0001; 02/08/2021: F(3,12) = 48.41, P < 0.0001). During the same year, a similar comparison between a farm strategy based on synthetic insecticide and two organic alternative strategies was designed in orchards B and C. Remarkably, in orchard B the treatments with diatomaceous earth resulted in low injury values, similar to those of the acetamiprid-treated plots (farm strategy). Treatments with B. bassiana ATCC 74040 provided lower efficacy in reducing the injury, but still higher efficacy than the untreated control (02/07/2021: F(3,12) = 42.05, P < 0.0001; 23/07/2021: F(3,12) = 23.28, P < 0.0001; 05/09/2021: F(3,12) = 68.58, P < 0.0001). Unlike orchard B, in orchard C, both the diatomaceous earth and the B. bassiana GHA treatments provided lower control than acetamiprid (farm strategy), although all treatments were effective compared to the untreated control (02/07/2021: F(3,12) = 179.35, P < 0.0001; 23/07/2021: F(3,12) = 101.92, P < 0.0001; 05/09/2021: F(3,12) = 33.20, P < 0.0001).

In 2022, two combined organic experimental strategies were compared to synthetic insecticide-based farm strategy in both orchards B and C. In orchard B, efficacy of sulphur type 2 + diatomaceous earth mixture and calcium polysulfide + diatomaceous earth mixture was similar to acetamiprid (farm strategy) in containing fruit injuries, with lower values compared to the untreated control (11/07/2022: F(3,12) = 11.87, P = 0.0007; 16/08/2022: F(3,12) = 45.07, P < 0.0001; 02/09/2022: F(3,12) = 31.92, P < 0.0001). In orchard C, sulphur type 2 + diatomaceous earth mixture provided higher efficacy compared to acetamiprid + diatomaceous earth mixture (farm strategy). Intermediate efficacy was provided by calcium polysulfide + diatomaceous earth mixture (11/07/2022: F(2,9) = 5.80, P = 0.024; 16/08/2022: F(2,9) = 4.36, P = 0.048; 02/09/2022: F(2,9) = 4.91, P = 0.036).

Discussion

Our laboratory experiments prove that several natural products allowed in organic farming can effectively control juvenile H. halys. In addition, organic experimental strategies tested in pear orchards were effective in reducing stink bug injuries to fruits, often with similar efficacy compared to strategy based on a chemical insecticide (acetamiprid). However, most of the tested organic products were also lethal to T. japonicus, thus non-target effects in the field on this important biocontrol agent must be addressed.

All products tested in the laboratory caused a higher mortality of H. halys than control, both at 4 and 7 days from application. Among the liquid insecticides, azadirachtin caused relevant mortality after 7 days, which was not significantly higher than that of potassium salts of fatty acids and orange oil. Azadirachtin, isolated from the seeds of Azadirachta indica (A. Juss), is a secondary metabolite with well-known insecticidal activity62. Our result is consistent with that obtained in a bioassay in which the application of the compound by insect submersion determined high mortality of H. halys nymphs (78%) and adults (55%)56. In another study, topical application of high concentrations of azadirachtin determined 86 to 100% mortality of Nezara viridula L. (Heteroptera: Pentatomidae) fifth instars63. Our data seem to controvert those by Lee, et al.55, who showed that dried residues of azadirachtin caused no mortality on H. halys over a 7-day period after exposition. However, in this case H. halys was tested at the adult stage and was exposed for a very short time. Notably, azadirachtin acts as antifeedant and determines moulting defects64, therefore its effects might continue for a longer period than 7 days, which thus should be investigated in future experiments. Interestingly, when we evaluated in the laboratory the effects of azadirachtin against T. japonicus, this insecticide caused the lowest percentage of mortality among all tested products. This is consistent with the lack of contact toxicity shown on the parasitoid Encarsia sophia (Girault and Dodd) (Hymenoptera: Aphelinidae)65. Regarding our results on potassium salts of fatty acids, their high lethal effect caused to H. halys nymphs is consistent with Lee, et al.55, who found a high mortality of H. halys adults in contact assays with this organic insecticide. Additionally it showed only moderate toxicity against T. japonicus. Suma, et al.66 noticed that Lysiphlebus spp. (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) emergence from sprayed parasitised aphids was not negatively affected by this insecticide. As regards orange oil, this product caused around 30% of H. halys juvenile mortality and low mortality to T. japonicus. Orange oil (Prev-Am) caused high mortality to soft-body insects, such as aphids and whiteflies, while only affected the behavioural response in the heteropteran predator Nesidiocoris tenuis (Reuter) (Heteroptera: Miridae)67,68. When Bracon nigricans Szépligeti (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) was exposed to 1-h pesticide residues, survival was higher than 80% and did not cause sub-lethal effects on parasitoid longevity and production of progeny compared to control69.

Among the dust products tested in our study, we observed high mortality of kaolin and zeolite on H. halys nymphs. Their repellent or deterrent activity on other pests, as psyllids, aphids, mites, fruit flies and also nymphs and adults of H. halys, has been investigated26,70,71,72. The other tested products, namely diatomaceous earth and basalt dust, are used for controlling stored product pests, for example 73,74,75, and are composed of silica, which determines insect desiccation76,77. In our experiments, both products induced mortality of H. halys nymphs at 4 and 7 days after application. However, although not at high level, all tested dusts induced lethal effects on the parasitoid T. japonicus. A few studies report on the lethal effects of these dusts on parasitoids, showing distinctive results. For example, contact with kaolin-treated surfaces did not induce mortality in Psyttalia concolor (Szèpligeti) (Hymenoptera: Braconidae), an endoparasitoid of Bactrocera oleae (Rossi) (Diptera: Tephritidae)78. On the contrary, a diatomaceous earth-based formulation induced high mortality rate on Anisopteromalus calandrae (Howard) (Hymenoptera: Pteromalidae), ectoparasitoid of Sitophilus oryzae (L.) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae)79.

Two types of sulphurs and their mixtures with zeolite and/or diatomaceous earth induced remarkable levels of nymph mortality. Exploitation of sulphurs for their fungicidal activity has a long history80,81. Moreover, sulphur-based formulations have been used for managing pests, especially mites82,83 and they are also known to have a deterrent/repellent effect on H. halys adults84,85. The efficacy of diatomaceous earth against H. halys was increased when combined with sulphur type 2 (Mannino) in laboratory conditions. The enhanced effect of diatomaceous earth on entomopathogenic activity is well known, so we can hypothesise that a similar mechanism may also occur with sulphur, which can induce arthropod mortality but whose true mode of action is still unknown (86,87,88 and references therein). Conversely, the high mortality of T. japonicus confirmed the side effects of sulphurs on parasitoids and predators31,89,90. Concerning calcium polysulfide, this product induced high H. halys mortality, thus confirming its already known toxicity against herbivores, such as mites, scales, and fruit flies91,92,93.

In 2021 field experiments, treatments with diatomaceous earth and acetamiprid (orchard B) showed similar efficacy, which indicates that the organic compound can be a safer alternative to the synthetic insecticide. Considering the future restrictions on the use of acetamiprid in the EU60 and reports of its side effects on T. japonicus behaviour94, this result can be of high relevance. Moreover, in the presence of high infestations of H. halys (> 60% of damaged fruits in the untreated plots of orchard A and B in 2021), treatments with both the diatomaceous earth and the two tested entomopathogens were effective in reducing fruit injuries, which highlights their efficacy in controlling pest attacks. Notably, in the 2022 field experiments, treatments of diatomaceous earth alternated with sulphur or calcium polysulfide were also effective in reducing fruit injury compared to the control plots (orchard B), or even to acetamiprid based farm strategy (orchard C). Because growth, and therefore efficacy, of entomopathogenic fungi are negatively affected by high temperatures that can be reached in field conditions (Supplementary materials Figure S2;95), the use of diatomaceous earth alternated with sulphur-based formulations could be preferred in field applications. In addition, such products may be more persistent than botanicals. For example, essential oils lack persistence and may undergo more rapid thermal and photodegradation than natural powders96.

Combining laboratory and field studies is pivotal to improve pest management strategies. Results from our research might suggest the use of diatomaceous earth in combination with sulphur-based biopesticides for management of H. halys. However, the persistence of these products should be evaluated in future studies as this may determine the frequency of field applications and the resulting economic and environmental impacts58,97. Side effects of these products on the biocontrol agent T. japonicus have been highlighted. This emphasizes that specific risk assessment on possible non-target effects is necessary even when combining organic management and natural enemies. Future studies should also evaluate parasitoid mortality at the larval stage, protected inside the host eggs58,97. The current parasitoid release strategy consists in the inoculation of physogastric females during the peaks of H. halys oviposition in natural areas, field edges, and green corridors98. In areas where it is necessary to ensure the establishment of T. japonicus, to avoid direct contact of foraging parasitoids with chemical pesticides, it is recommended that parasitoids are released at a safe distance of at least 100 m from herbaceous crops and orchards99. The effect of exposure to low (sublethal) doses of natural products on parasitoid foraging behaviour should also be evaluated, as non-lethal effects may alter parasitoid efficacy in the field69,100. Evaluation of residual toxicity after application of natural products would provide information on the safe interval for parasitoid release. Finally, further field experiments should consider additional products, like azadirachtin and potassium salts of fatty acids, which provided good levels of lethality against H. halys juveniles.

Methods

Insect rearing

Halyomorpha halys

The H. halys colony was established by collecting adults during spring and summer 2021 from herbaceous crops, uncultivated areas, and fruit orchards in Northern Italy. Collections were carried out by means of sweeping nets or visual hand picking on grasses, bushes, and trees. About 60 adults collected in the field were transferred to the laboratory and reared in mesh cages (Kweekkooi, 40 × 40 × 60 cm, Vermandel, Hulst, The Netherlands) under controlled environmental conditions (25 ± 1 °C, 60 ± 5% RH and 16/8 h L/D). Daily collected egg masses were used fresh, to maintain the stink bug colony, or frozen at -20 °C to rear the parasitoids. Stink bugs were reared as follows. An upside-down glass jar filled with water and sealed with cotton to the bottom of a Petri dish was used for water supply. Diet consisted of tomato fruits, carrots, sunflower seeds and green bean pods. The diet was changed three times a week. For the laboratory experiments, groups of ten 2nd instars H. halys were exposed to treatments or control. Diet of nymphs used for the experiments included only a fresh green bean pod.

Trissolcus japonicus

The T. japonicus colony derived from the original strain provided by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) (details in51,101). The population was maintained by exposing frozen H. halys egg masses to mated female parasitoids (one female per egg mass). Parasitoids were reared in Falcon TM tubes (50 ml) and kept in a climatic chamber at controlled conditions (25 ± 1 °C, 60 ± 5% RH, 16/8 h L/D). The diet consisted of pure honey droplets dispensed on a piece (2 × 2 cm) of laboratory film (Parafilm, Bemis, USA). Tests were performed with groups of ten T. japonicus females, approximately 7-days old.

Laboratory lethal effect assays on Halyomorpha halys

The laboratory experiments were designed to provide an evaluation of the lethal effects of different natural products on H. halys nymphs exposed by contact. Nymphs were placed in treated or untreated 280 ml transparent polypropylene cups with seal lid (Plastitalia Group s.r.l., Florence). The lid presented opening holes (1.5 mm diameter) to allow air exchange. Four experiments were carried out based on the type of product tested, which were: (1) liquid insecticide formulations; (2) siliceous rock and clay dusts; (3) dust-formulations of sulphur products and their mixtures with dusts; and (4) liquid formulation of calcium polysulfide. All products were applied simulating the recommended field doses for fruit trees. Liquid formulations were distributed on the internal cup surface using a low-pressure airbrush at the volume of 1.4 ml of solution (biopesticide plus distilled water). Instead, dusts were distributed using a paint brush at the amount of 15 mg to cover the internal cup surface. Water-treated or clean plastic cups were used as control. In details, in Experiment 1, the following liquid insecticides were tested: azadirachtin (Oikos, Sipcam Oxon S.p.A, Milan, Italy; field dose: 1.2 ml/L), orange oil (Prev-Am Plus, Oro Agri Europe S.A., Portugal; field dose: 3 ml/L), and potassium salts of fatty acids (Flipper, Alpha Biopesticides Ltd, United Kingdom; field dose: 20 ml/L). In Experiment 2, different dust products were used. These were kaolin (“Polvere di roccia”, CBC Europe S.r.l. Biogard division, Bergamo, Italy), basalt dust (“Farina di Basalto XF”, Basalti Orvieto S.r.l., Terni, Italy), zeolite with more than 50% chabazite (“Zem 70”, Bal-co Spa, Modena, Italy), and diatomaceous earth (“Farina fossile”, Palumbo Trading srl, Milan, Italy); all dusts were applied at a field dose of 30 kg/ha. In Experiment 3, sulphur-based products and their mixtures with dust insecticides were evaluated. Specifically, we tested ventilated sulphur type 1 (“Zolfo doppio ventilato raffinato”; Manica Spa, Trento, Italy), ventilated sulphur type 2 (“Zolfo triventilato scorrevole 95% S”; Zolfi Ventilati Mannino Spa, Agrigento, Italy), sulphur type 1 plus zeolite (40–60% mixture), sulphur type 2 + zeolite (50–50% mixture), and sulphur type 2 + diatomaceous earth (50–50% mixture); all were tested at the dose of 30 kg/ha. In Experiment 4, calcium polysulfide (Polisenio S.r.l, Ravenna, Italy), a fungicide normally obtained adding quicklime (CaO) to sulphur91, was used. The tested concentrations were 20, 30, and 50 g/L, which are those recommended for field application on different crops. In all trials, H. halys nymphs were kept in a climatic chamber at 25 ± 1 °C, 70 ± 5% RH, and at 16/8 h L/D. Five replicates were conducted for each product and control, and 10 insects were tested in each replicate. The mortality rate was evaluated after 4 and 7 days from product application. Insects were considered dead when not moving after being touched with a paintbrush.

Laboratory lethal effect assays on Trissolcus japonicus

Munger cells were used to assess the lethal contact effects of natural products on parasitoid females102,103. The experiments were conducted in a closed arena consisting of a polycarbonate plate (90 × 90 × 8 mm thickness, with a central circular hole of 60 mm diameter) with two brass net-covered ventilations holes (0.4 cm diameter) vertically located in two opposite sides of the plate. The arena was sandwiched between two glass plates (90 × 90 × 5 mm thick), and the lower part was covered with filter paper used as the walking contact surface, both in treatments and control. All products tested on H. halys were also tested on the parasitoid, except for the dust-sulphur mixtures. As for H. halys, the field doses of each product were used also for the parasitoid according to manufacturer’s specifications. Liquid formulations of the products or distilled water (for control) were applied to filter paper at the volume of 0.4 ml. Filter papers were then left to dry under a hood for 1 h. Tested products, formulations and doses (or concentrations in the case of solutions) were as follows. Liquid insecticides were: azadirachtin (1.2 ml/L), orange oil (3 ml/L), potassium salts of fatty acids (20 ml/L). Kaolin, basalt dust, zeolite, diatomaceous earth, as well as sulphur type 1 and 2 were applied at 0.0085 g dosage. The only liquid fungicide was polysulfide (30 g/L). Adults of T. japonicus were exposed to the products for a period of 7 days, and, as for H. halys, lethality was observed at 4 and 7 days. A diet of honey droplets was dispensed on the walls of the arena. Four replicates were carried out for each product and ten parasitoid females were tested for each replicate. As for stink bugs, insects were considered dead when not moving after being touched with a paintbrush. Bioassayed insects were kept at the same controlled conditions of the parasitoid colony.

Field experiments and fruit injury evaluation

The field experiments were performed in pear orchards along two years and involved three farms in 2021 (orchards A, B and C) and two farms in 2022 (orchards B and C) (Table 4). The orchards are located in the Modena and Ferrara provinces (North Italy; orchard A: 44°52’18.8"N 10°59’45.4"E; orchard B: 44°50’08.6"N 11°48’49.6"E; orchard C: 44°50’26.9"N 11°48’54.4"E). Orchard A is an organic cultivation of Pyrus communis L. var. William (1200 m2; 8 rows; trees are planted at 1 m distance and rows are interspaced by 4 m; 8 years old), while orchards B (1152 m2; 12 rows; trees at 0.8 m distance, interspace 2.4 m between rows; 11 years old) and C (1152 m2; 12 rows; trees at 0.8 m distance, interspace 2.4 m between rows; 9 years old) are integrated cropping systems with P. communis var. Abate Fétel. For the experiments, orchards were divided into 4 plots (3 in the case of orchard C in 2022), each used for a different treatment (in orchard A each plot was 300 m2, 2 rows; in Orchard B and C each plot was 288 m2, 3 rows). To achieve a satisfying coverage of plants, liquid treatments were applied using a Maruyama MS0835W backpack motor pump with “CONHOLE 03” nozzles at a pressure of 5 bar, while for powder applications, a Stihl SR 450 was used. To evaluate and count damaged fruits, each plot was further divided into four sub-plots where a sample of about 100 fruits per sub-plot was examined for possible presence of feeding damage by H. halys.

Details of the experiments are shown in Table 4. In each orchard the farm strategy for organic (treated control, organic management) or integrated management of H. halys (treated control, integrated management) was compared with alternative experimental strategies (experimental treatments) and with plots treated with water (untreated control). Six different experimental strategies were chosen according to literature data and preliminary in-farm experiments, combined with unavoidable farm constraints and market-based choices. Because the laboratory and field experiments were conducted simultaneously, it was not possible to design field experiments based to laboratory results.

In 2021, the experimental treatments contemplated the diatomaceous earth and the entomopathogenic fungi B. bassiana (strains ATCC 74040 and GHA) and A. muscarius, both species known for their use against several insect taxa104,105,106,107. Beauveria bassiana was previously found causing high lethality in nymphs and adults of H. halys under laboratory conditions52,108. Akanthomyces muscarius was effective in the laboratory against a related stink bug species, Palomena prasina (L.) (Hem.: Pentatomidae)109. The farm strategies and experimental treatments were different in the three orchards. In orchard A the organic farm strategy was diatomaceous earth (Palumbo; 10 applications), whereas the experimental treatments were A. muscarius Ve6 (Mycotal, Koppert B. V., Netherlands; 10 applications) and B. bassiana GHA (Botanigard OD, Certis Europe B.V., Utrecht, Netherlands; 10 applications). Only water was applied in the untreated control. In orchard B the farm strategy was based on acetamiprid (Epik SL, Sipcam Italia S.p.A., Milan, Italy; or Kestrel, Nufarm Italia S.r.l., Milan, Italy; or Gazelle, Sipcam Italia S.p.A., Milan, Italy; 5 applications totally) while the experimental treatments consisted of diatomaceous earth (Palumbo; 11 applications) and B. bassiana ATCC 74040 (Naturalis, CBC Europe S.r.l., Bergamo, Italy; 11 applications). Only water was applied in the untreated control. In orchard C the farm strategy was also based on acetamiprid (Epik SL or Kestrel; 4 applications), whereas the experimental treatments consisted of diatomaceous earth (Palumbo; 12 applications) and B. bassiana GHA (Botanigard OD; 12 applications). This orchard also included an untreated control plot.

In 2022, the experimental treatments were different from 2021 and were focused on diatomaceous earth combined with calcium polysulfide or sulphur. The experiments were conducted only in orchards B and C. In orchard B, the farm strategy was based on acetamiprid (Epik SL or Kestrel; 3 applications), while the experimental treatments were diatomaceous earth (Palumbo; 30 kg/ha) in an alternated weekly application with calcium polysulfide (Polisenio; 600 L/ha; 15 combinate applications), or with sulphur type 2 (Mannino; 30 kg/ha; 15 combinate applications). An untreated control plot was included. In orchard C the farm strategy was different from prior year, as acetamiprid (Epik SL or Kestrel; 3 applications) was alternated with diatomaceous earth (Palumbo; 7 applications). The experimental treatments were as in orchard B, whereas no untreated control was included.

As a general rule, in both years the timing of the first application coincided with the emergence of H. halys from the overwintering sites, based on the captures recorded in the monitoring traps (Supplementary materials Figure S1), and treatments continued until harvest. Samples of about 400 fruits were randomly collected for each treatment and control. Only fruits located in the central part of row were sampled, thus excluding the border. Three injury evaluations were performed during the season. Each fruit was inspected for fruit injuries. External fruit injuries were evaluated using one of the following code: 0 (intact fruit), 1 (damaged fruit), 2 (severely deformed fruit) (similarly to110).

Statistical analysis

Mortality of H. halys and T. japonicus in laboratory conditions was corrected using Abbott’s formula111,112. Differences between treatments (arcsine transformed) were analysed by means of linear models (LMs) followed by multiple comparisons procedure (significance level, alpha = 0.05). For each experiment, the significance vs. the untreated control was extrapolated from the model. For 2021 and 2022 field trials, percentages of injured fruits were calculated using the Townsend–Heuberger formula113,114. Data were analysed by means of linear models in R statistical environment115.

Data availability

The data generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Change history

31 July 2025

The original online version of this Article was revised: In the original version of this Article the Acknowledgements section was incomplete. The Acknowledgements section now reads: “The authors are grateful to Ciro Lazzarin, Mauro Gavioli, Costantino Pellati, Antonio Trovò, Andrea Luchetti and Daniela Fortini for administrative, laboratory and field assistance. Funding was partly provided by the Emilia-Romagna Region with the project “PSR 2014–2020, measure 16.1.01, Sistemi integrati sostenibili di comprensorio per il controllo della cimice asiatica (Halyomorpha halys), acronym S.I.S.C.C.C.A.”. GR was funded by H2020-MSCA-IF, Grant agreement ID: 101026399. This research was carried out within the framework of the project “Innovative farm strategies that integrate sustainable N fertilization, water management and pest control to reduce water and soil pollution and salinization in the Mediterranean-Safe-H2O-Farm The Safe-H2O-Farm is part of the PRIMA Program supported by the European Union with co-funding from the Italian Ministry of University and Research."

References

Seebens, H. et al. Projecting the continental accumulation of alien species through to 2050. Glob. Change Biol. 27, 970–982 (2021).

Vitousek, P. M., D’antonio, C. M., Loope, L. L., Rejmanek, M. & Westbrooks, R. Introduced species: a significant component of human-caused global change. New. Z. J. Ecol. 21, 1–16 (1997).

Meyerson, L. A. & Mooney, H. A. Invasive alien species in an era of globalization. Front. Ecol. Environ. 5, 199–208 (2007).

Tobin, P. C. Managing invasive species. F1000Research 7, 1686 (2018).

Pysek, P. et al. Scientists’ warning on invasive alien species. Biol. Rev. 95, 1511–1534 (2020).

Seebens, H. et al. No saturation in the accumulation of alien species worldwide. Nat. Commun. 8, 14435 (2017).

Barzman, M. et al. Eight principles of integrated pest management. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 35, 1199–1215 (2015).

Damos, P., Colomar, L. A. & Ioriatti, C. Integrated fruit production and pest management in Europe: the apple case study and how far we are from the original concept? Insects 6, 626–657 (2015).

Shawer, R., Tonina, L., Tirello, P., Duso, C. & Mori, N. Laboratory and field trials to identify effective chemical control strategies for integrated management of Drosophila suzukii in European cherry orchards. Crop Prot. 103, 73–80 (2018).

Guedes, R. N. C. et al. Insecticide resistance in the tomato pinworm Tuta absoluta: patterns, spread, mechanisms, management and outlook. J. Pest Sci. 92, 1329–1342 (2019).

Tabet, D. H. et al. Efficacy of insecticides against the invasive apricot aphid, Myzus mumecola. Insects 14, 746 (2023).

Wang, Z., Yan, H., Yang, Y. & Wu, Y. Biotype and insecticide resistance status of the whitefly Bemisia tabaci from China. Pest Manag. Sci. 66, 1360–1366 (2010).

Campos, M. R. et al. Spinosad and the tomato borer Tuta absoluta: a bioinsecticide, an invasive pest threat, and high insecticide resistance. PLoS One. 9, e103235 (2014).

Siddiqui, J. A. et al. Insights into insecticide-resistance mechanisms in invasive species: challenges and control strategies. Front. Physiol. 13, 1112278 (2023).

Nicolopoulou-Stamati, P., Maipas, S., Kotampasi, C., Stamatis, P. & Hens, L. Chemical pesticides and human health: the urgent need for a new concept in agriculture. Front. Public. Health. 4, 148 (2016).

Rani, L. et al. An extensive review on the consequences of chemical pesticides on human health and environment. J. Clean. Prod. 283, 124657 (2021).

Karabelas, A. J., Plakas, K. V., Solomou, E. S., Drossou, V. & Sarigiannis, D. A. Impact of European legislation on marketed pesticides–a view from the standpoint of health impact assessment studies. Environ. Int. 35, 1096–1107 (2009).

Hillocks, R. J. Farming with fewer pesticides: EU pesticide review and resulting challenges for UK Agriculture. Crop Prot. 31, 85–93 (2012).

Jactel, H. et al. Alternatives to neonicotinoids. Environ. Int. 129, 423–429 (2019).

Pavela, R. & Benelli, G. Essential oils as ecofriendly biopesticides? Challenges and constraints. Trends Plant Sci. 21, 1000–1007 (2016).

Giunti, G. et al. Repellence and acute toxicity of a nano-emulsion of sweet orange essential oil toward two major stored grain insect pests. Ind. Crops Prod. 142, 111869 (2019).

Rizzo, R. et al. Bioactivity of Carlina acaulise essential oil and its main component towards the olive fruit fly, Bactrocera oleae: ingestion toxicity, electrophysiological and behavioral insights. Insects 12, 880 (2021).

Copping, L. G. & Menn, J. J. Biopesticides: a review of their action, applications and efficacy. Pest Manag. Sci. 56, 651–676 (2000).

Chandler, D. et al. The development, regulation and use of biopesticides for integrated pest management. Philosophical Trans. Royal Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 366, 1987–1998 (2011).

Daher, E. et al. Field and laboratory efficacy of low-impact commercial products in preventing olive fruit fly, Bactrocera oleae, infestation. Insects 13, 213 (2022).

Daher, E. et al. Characterization of olive fruit damage induced by invasive Halyomorpha halys. Insects 14, 848 (2023).

Gao, Y., Reitz, S. R., Wang, J., Xu, X. & Lei, Z. Potential of a strain of the entomopathogenic fungus Beauveria bassiana (Hypocreales: Cordycipitaceae) as a biological control agent against western flower thrips, Frankliniella occidentalis (Thysanoptera: Thripidae). Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 22, 491–495 (2012).

Wu, S., He, Z., Wang, E., Xu, X. & Lei, Z. Application of Beauveria bassiana and Neoseiulus barkeri for improved control of Frankliniella occidentalis in greenhouse cucumber. Crop Prot. 96, 83–87 (2017).

Zhang, X., Lei, Z., Reitz, S. R., Wu, S. & Gao, Y. Laboratory and greenhouse evaluation of a granular formulation of Beauveria bassiana for control of western flower thrips, Frankliniella occidentalis. Insects 10, 58 (2019).

Williams, T., Valle, J. & Viñuela, E. Is the naturally derived Insecticide Spinosad® Compatible with Insect Natural enemies? Biocontrol Sci. Technol.13, 459–475 (2003).

Jepsen, S. J., Rosenheim, J. A. & Bench, M. E. The effect of sulfur on biological control of the grape leafhopper, Erythroneura elegantula, by the egg parasitoid Anagrus erythroneurae. BioControl 52, 721–732 (2007).

Babin, A., Lemauf, S., Rebuf, C., Poirié, M. & Gatti, J. L. Effects of Bacillus thuringiensis kurstaki bioinsecticide on two non-target Drosophila larval endoparasitoid wasps. Entomol. Generalis. 42, 611–620 (2022).

Giunti, G. et al. Non-target effects of essential oil-based biopesticides for crop protection: impact on natural enemies, pollinators, and soil invertebrates. Biol. Control. 176, 105071 (2022).

Desneux, N., Decourtye, A. & Delpuech, J. M. The sublethal effects of pesticides on beneficial arthropods. Ann. Rev. Entomol. 52, 81–106 (2007).

Biondi, A., Desneux, N., Siscaro, G. & Zappala, L. Using organic-certified rather than synthetic pesticides may not be safer for biological control agents: selectivity and side effects of 14 pesticides on the predator Orius laevigatus. Chemosphere 87, 803–812 (2012).

Teder, T. & Knapp, M. Sublethal effects enhance detrimental impact of insecticides on non-target organisms: a quantitative synthesis in parasitoids. Chemosphere 214, 371–378 (2019).

Parsaeyan, E., Saber, M., Safavi, S. A., Poorjavad, N. & Biondi, A. Side effects of chlorantraniliprole, phosalone and spinosad on the egg parasitoid, Trichogramma brassicae. Ecotoxicology 29, 1052–1061 (2020).

Passos, L. C. et al. Sublethal effects of plant essential oils toward the zoophytophagous mirid Nesidiocoris tenuis. J. Pest Sci. 95, 1609–1619 (2022).

Stenberg, J. A. A conceptual framework for integrated pest management. Trends Plant Sci. 22, 759–769 (2017).

Tiwari, A. K.. IPM Essentials Combining Biology, Ecology, and Agriculture for sustainable Pest Control. J. Adv. Biology Biotechnol. 27, 39–47 (2024).

Cock, M. J. W. et al. Trends in the classical biological control of insect pests by insects: an update of the BIOCAT database. BioControl 61, 349–363 (2016).

Kenis, M., Hurley, B. P., Hajek, A. E. & Cock, M. J. W. classical biological control of insect pests of trees: facts and figures. Biol. Invasions. 19, 3401–3417 (2017).

Kriticos, D. J. et al. The potential global distribution of the brown marmorated stink bug, Halyomorpha halys, a critical threat to plant biosecurity. J. Pest Sci. 90, 1033–1043 (2017).

Leskey, T. C. & Nielsen, A. L. Impact of the invasive brown marmorated stink bug in North America and Europe: history, biology, ecology, and management. Ann. Rev. Entomol. 63, 599–618 (2018).

van der Heyden, T., Saci, A. & Dioli, P. First record of the brown marmorated stink bug Halyomorpha halys (Stål, 1855) in Algeria and its presence in North Africa (Heteroptera: Pentatomidae). Revista Gaditana De Entomología. 12, 147–154 (2021).

Leskey, T. C. et al. Pest Status of the Brown Marmorated Stink bug, Halyomorpha Halys in the USA. Outlooks Pest Manage. 23, 218–226 (2012).

Haye, T., Abdallah, S., Gariepy, T. & Wyniger, D. Phenology, life table analysis and temperature requirements of the invasive brown marmorated stink bug, Halyomorpha halys, in Europe. J. Pest Sci. 87, 407–418 (2014).

Bariselli, M., Bugiani, R. & Maistrello, L. Distribution and damage caused by Halyomorpha halys in Italy. EPPO Bull. 46, 332–334 (2016).

Yang, Z. Q., Yao, Y. X., Qiu, L. F. & Li, Z. X. A new species of Trissolcus (Hymenoptera: Scelionidae) parasitizing eggs of Halyomorpha halys (Heteroptera: Pentatomidae) in China with comments on its biology. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 102, 39–47 (2009).

Haye, T. et al. Fundamental host range of Trissolcus japonicus in Europe. J. Pest Sci. 93, 171–182 (2020).

Sabbatini-Peverieri, G. et al. Combining physiological host range, behavior and host characteristics for predictive risk analysis of Trissolcus japonicus. J. Pest Sci. 94, 1003–1016 (2021).

Parker, B. L., Skinner, M., Gouli, S., Gouli, V. & Kim, J. S. Virulence of BotaniGard(R) to second Instar Brown Marmorated Stink bug, Halyomorpha halys (Stal) (Heteroptera: Pentatomidae). Insects 6, 319–324 (2015).

Tozlu, E. et al. Potentials of some entomopathogens against the brown marmorated stink bug, Halyomorpha halys (Stål, 1855) (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae). Egypt. J. Biol. Pest Control 29 (2019).

Gonella, E., Orrù, B. & Alma, A. Symbiotic control of Halyomorpha halys using a microbial biopesticide. Entomol. Generalis. 42, 901–909 (2022).

Lee, D. H., Short, B. D., Nielsen, A. L. & Leskey, T. C. Impact of Organic insecticides on the Survivorship and mobility of Halyomorpha halys(Stål) (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) in the Laboratory. Fla. Entomol. 97, 414–421 (2014).

Morehead, J. A. & Kuhar, T. P. Efficacy of organically approved insecticides against brown marmorated stink bug, Halyomorpha halys and other stink bugs. J. Pest Sci. 90, 1277–1285 (2017).

Lowenstein, D. M., Andrews, H., Mugica, A. & Wiman, N. G. Sensitivity of the egg parasitoid trissolcus japonicus (Hymenoptera: Scelionidae) to field and laboratory applied insecticide residue. J. Econ. Entomol. 112, 2077–2084 (2019).

Ribeiro, A. V., Holle, S. G., Hutchison, W. D. & Koch, R. L. Lethal and sublethal effects of conventional and organic insecticides on the parasitoid Trissolcus japonicus, a biological control agent for Halyomorpha halys. Front. Insect Sci. 1, 685755 (2021).

Fouani, J. M. et al. Dose-response and sublethal effects from insecticide and adjuvant exposure on key behaviors of Trissolcus japonicus. Entomol. Generalis. 2024, 1–9 (2024).

EFSA. Statement on the toxicological properties and maximum residue levels of acetamiprid and its metabolites. EFSA J. 22, e8759 (2024).

Falagiarda, M. et al. Factors influencing short-term parasitoid establishment and efficacy for the biological control of Halyomorpha halys with the samurai wasp trissolcus japonicus. Pest Manag. Sci. 79, 2397–2414 (2023).

Mordue, A. J. & Blackwell, A. Azadirachtin: an update. J. Insect. Physiol. 39, 903–924 (1993).

Riba, M., Martí, J. & Sans, A. Influence of azadirachtin on development and reproduction of Nezara viridula L. (Het., Pentatomidae). J. Appl. Entomol. 127, 37–41 (2003).

Morgan, E. D. Azadirachtin, a scientific gold mine. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 17, 4096–4105 (2009).

Aggarwal, N. & Brar, D. S. Effects of different neem preparations in comparison to synthetic insecticides on the whitefly parasitoid Encarsia sophia (Hymenoptera: Aphelinidae) and the predator Chrysoperla carnea (Neuroptera: Chrysopidae) on cotton under laboratory conditions. J. Pest Sci. 79, 201–207 (2006).

Suma, P., Cocuzza, G. M., Maffioli, G. & Convertini, S. Efficacy of a fast acting contact bio insecticide-acaricide of vegetable origin in controlling greenhouse insect pests. IOBC-WPRS Bull. 147, 141–143 (2019).

Smith, G. H., Roberts, J. M. & Pope, T. W. Terpene based biopesticides as potential alternatives to synthetic insecticides for control of aphid pests on protected ornamentals. Crop Prot. 110, 125–130 (2018).

Soares, M. A. et al. Detrimental sublethal effects hamper the effective use of natural and chemical pesticides in combination with a key natural enemy of Bemisia tabaci on tomato. Pest Manag. Sci. 76, 3551–3559 (2020).

Biondi, A., Zappala, L., Stark, J. D. & Desneux, N. Do biopesticides affect the demographic traits of a parasitoid wasp and its biocontrol services through sublethal effects? PLoS One. 8, e76548 (2013).

Glenn, D. M., Puterka, G. J., Vanderzwet, T., Byers, R. E. & Feldhake, C. Hydrophobic particle films: a new paradigm for suppression of arthropod pests and plant diseases. J. Econ. Entomol. 92, 759–771 (1999).

De Smedt, C., Someus, E. & Spanoghe, P. Potential and actual uses of zeolites in crop protection. Pest Manag. Sci. 71, 1355–1367 (2015).

Kuhar, T. P., Morehead, J. A. & Formella, A. J. Applications of kaolin protect fruiting vegetables from brown marmorated stink bug (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae). J. Entomol. Sci. 54, 401–408 (2019).

Golob, P. Current status and future perspectives for inert dusts for control of stored product insects. J. Stored Prod. Res. 33, 69–79 (1997).

Korunic, Z. Diatomaceous earths, a group of natural insecticides. J. Stored Prod. Res. 34, 87–97 (1998).

Zeni, V., Baliota, G. V., Benelli, G., Canale, A. & Athanassiou, C. G. Diatomaceous earth for arthropod pest control: back to the future. Molecules 26, 7487 (2021).

Shah, M. A. & Khan, A. A. Use of diatomaceous earth for the management of stored-product pests. Int. J. Pest Manage. 60, 100–113 (2014).

Elimem, M. et al. Evaluation of insecticidal efficiency of basalt powder Farina Di Basalto® to control Tribolium castaneum (Coleoptera, Tenebrionidae), Rhyzopertha dominica (Coleoptera, Bostrichidae) and Ephestia kuehniella (Lepidoptera, Pyralidae) on stored wheat. J. Agric. Veterinary Sci.14, 1–6 (2021).

Bengochea Budia, P. Side effects of kaolin on natural enemies found on olive crops. IOBC WPRS Bull. 55, 61–67 (2010).

Perez-Mendoza, J., Baker, J. E., Arthur, F. H. & Flinn, P. W. Effects of Protect-It on efficacy of Anisopteromalus calandrae (Hymenoptera: Pteromalidae) parasitizing rice weevils (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) in wheat. Environ. Entomol. 28, 529–534 (1999).

Williams, J. S. & Cooper, R. M. The oldest fungicide and newest phytoalexin – a reappraisal of the fungitoxicity of elemental sulphur. Plant. Pathol. 53, 263–279 (2004).

Devendar, P. & Yang, G. F. Sulfur-containing agrochemicals. Top. Curr. Chem. 375, 82 (2017).

Griffith, C. M., Woodrow, J. E. & Seiber, J. N. Environmental behavior and analysis of agricultural sulfur. Pest Manag. Sci. 71, 1486–1496 (2015).

Dahlawi, S. M. & Siddiqui, S. Calcium polysulphide, its applications and emerging risk of environmental pollution-a review article. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 24, 92–102 (2017).

Scaccini, D. et al. Application of sulfur-based products reduces Halyomorpha halys infestation and damage in pome fruit orchards. Pest Manag. Sci. 80, 6251–6261 (2024).

Scaccini, D. et al. Wettable sulphur application for Halyomorpha halys (Stal) (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) management: laboratory and semi-field experiments. Pest Manag. Sci. 80, 3620–3627 (2024).

Akbar, W., Lord, J. C., Nechols, J. R. & Howard, R. W. Diatomaceous earth increases the efficacy of Beauveria bassiana against Tribolium castaneum larvae and increases conidia attachment. J. Econ. Entomol. 97, 273–280 (2004).

Athanassiou, C. G. & Steenberg, T. Insecticidal effect of Beauveria bassiana (Balsamo) Vuillemin (Ascomycota: Hypocreaes) in combination with three diatomaceous earth formulations against Sitophilus granarius (L.) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). Biol. Control. 40, 411–416 (2007).

Wakil, W. et al. Entomopathogenic fungus and enhanced diatomaceous earth: the sustainable lethal combination against Tribolium castaneum. Sustainability 15, 4403 (2023).

Thompson, G. D., Dutton, R. & Sparks, T. C. Spinosad - a case study: an example from a natural products discovery programme. Pest Manag. Sci. 56, 696–702 (2000).

Zappalà, L. et al. Efficacy of sulphur on Tuta absoluta and its side effects on the predator Nesidiocoris tenuis. J. Appl. Entomol. 136, 401–409 (2012).

Beers, E. H., Martinez-Rocha, L., Talley, R. R. & Dunley, J. E. Lethal, sublethal, and behavioral effects of sulfur-containing products in bioassays of three species of orchard mites. J. Econ. Entomol. 102, 324–335 (2009).

Andreazza, F. et al. Toxicity to and egg-laying avoidance of Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae) caused by an old alternative inorganic insecticide preparation. Pest Manag. Sci. 74, 861–867 (2018).

Golan, K., Kot, I. & Kmieć, K. Górska-Drabik, E. approaches to integrated pest management in orchards: Comstockaspis perniciosa (Comstock) case study. Agriculture 13, 131 (2023).

Rondoni, G. et al. How exposure to a neonicotinoid pesticide affects innate and learned close-range foraging behaviour of a classical biological control agent. Biol. Control. 196, 105568 (2024).

Mishra, S., Kumar, P. & Malik, A. Effect of temperature and humidity on pathogenicity of native Beauveria bassiana isolate against Musca domestica L. J. Parasitic Dis. 39, 697–704 (2015).

Nenaah, G. E., Ibrahim, S. I. A. & Al-Assiuty, B. A. Chemical composition, insecticidal activity and persistence of three Asteraceae essential oils and their nanoemulsions against Callosobruchus maculatus (F). J. Stored Prod. Res. 61, 9–16 (2015).

Ludwick, D. C. et al. Trissolcus japonicus (Ashmead, (Hymenoptera: Scelionidae) into management programs for Halyomorpha halys (Stal, 1855) (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) in apple orchards: Impact of insecticide applications and spray patterns. Insects 11 (2020). (1904).

Simaz, O. et al. Field releases of the exotic parasitoid Trissolcus japonicus (Hymenoptera: Scelionidae) and survey of native parasitoids attacking Halyomorpha halys (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) in Michigan. Environ. Entomol. 52, 998–1007 (2023).

Paul, R. L. et al. An effective fluorescent marker for tracking the dispersal of small insects with field evidence of mark-release-recapture of Trissolcus japonicus. Insects 15 (2024).

Penagos, D. I., Cisneros, J., Hernández, O. & Williams, T. Lethal and sublethal effects of the naturally derived insecticide spinosad on parasitoids of Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 15, 81–95 (2005).

Chierici, E., Sabbatini-Peverieri, G., Roversi, P. F., Rondoni, G. & Conti, E. Phenotypic plasticity in an egg parasitoid affects olfactory response to odors from the plant–host complex. Front. Ecol. Evol. 11, 1233655 (2023).

Hassan, S. A. et al. Standard methods to test the side-effects of pesticides on natural enemies of insects and mites developed by the IOBC/WPRS Working Group ‘Pesticides and beneficial organisms’. Eppo Bull. 15, 214–255 (1985).

Morse, J. G., Bellows, T. S. & Iwata, Y. Technique for evaluating residual toxicity of pesticides to motile insects. J. Econ. Entomol. 79, 281–283 (1986).

Feng, M. G., Poprawski, T. J. & Khachatourians, G. G. Production, formulation and application of the entomopathogenic fungus Beauveria bassiana for insect control: current status. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 4, 3–34 (1994).

de Faria, M. R. & Wraight, S. P. Mycoinsecticides and mycoacaricides: a comprehensive list with worldwide coverage and international classification of formulation types. Biol. Control. 43, 237–256 (2007).

Goettel, M. S. et al. Potential of Lecanicillium spp. for management of insects, nematodes and plant diseases. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 98, 256–261 (2008).

Wang, H., Peng, H., Li, W., Cheng, P. & Gong, M. The toxins of Beauveria bassiana and the strategies to improve their virulence to insects. Front. Microbiol. 12, 705343 (2021).

Gouli, V. et al. Virulence of select entomopathogenic fungi to the brown marmorated stink bug, Halyomorpha halys (Stal) (Heteroptera: Pentatomidae). Pest Manag. Sci. 68, 155–157 (2012).

Ozdemir, I. O., Tuncer, C. & Ozer, G. Molecular characterisation and efficacy of entomopathogenic fungi against the green shield bug Palomena prasina (L.) (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) under laboratory conditions. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 31, 1298–1313 (2021).

Fornasiero, D., Scaccini, D., Lombardo, V., Galli, G. & Pozzebon, A. Effect of exclusion net timing of deployment and color on Halyomorpha halys (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) infestation in pear and apple orchards. Crop Prot. 172, 106331 (2023).

Abbott, W. S. A method of computing the effectiveness of an insecticide. J. Econ. Entomol. 18, 265–267 (1925).

Ahmad, M., Kamran, M., Abbas, M. N. & Shad, S. A. Ecotoxicological risk assessment of combined insecticidal and thermal stresses on Trichogramma chilonis. J. Pest Sci. 97, 921–931 (2023).

Masetti, A. et al. Evaluation of an attract-and-kill strategy using long-lasting insecticide nets for the management of the brown marmorated stink bug in Northern Italy. Insects 15, 577 (2024).

Townsend, G. R. & Heubergeb, J. W. Methods for estimating losses caused by diseases in fungicide experiments. Plant. Disease Report. 27, 340–343 (1943).

R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Ciro Lazzarin, Mauro Gavioli, Costantino Pellati, Antonio Trovò, Andrea Luchetti and Daniela Fortini for administrative, laboratory and field assistance. Funding was partly provided by the Emilia-Romagna Region with the project “PSR 2014–2020, measure 16.1.01, Sistemi integrati sostenibili di comprensorio per il controllo della cimice asiatica (Halyomorpha halys), acronym S.I.S.C.C.C.A.”. GR was funded by H2020-MSCA-IF, Grant agreement ID: 101026399. This research was carried out within the framework of the project “Innovative farm strategies that integrate sustainable N fertilization, water management and pest control to reduce water and soil pollution and salinization in the Mediterranean-Safe-H2O-Farm. The Safe-H2O-Farm is part of the PRIMA Program supported by the European Union with co-funding from the Italian Ministry of University and Research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E. M., A. R., G. R. and E.Co. conceived the manuscript. E.Ch., E.M., A.R., G.R., and E. Co. developed the methodology. E.Ch., E.M., A.P., A.R., V.A.G., L.G., L.Z., and G.R. conducted investigations. E.Ch., E.M., A.P., A.R., and G.R. curated the datasets. E.Ch., E.M., and G.R. analysed the data. E.M., A.R., G.R., and E.Co. supervised the research. E.Ch., A.P., G.R., and E.Co. wrote the first draft. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chierici, E., Marchetti, E., Poccia, A. et al. Laboratory and field efficacy of natural products against the invasive pest Halyomorpha halys and side effects on the biocontrol agent Trissolcus japonicus. Sci Rep 15, 4622 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87325-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87325-9