Abstract

The current piston material, Al-12Si, lacks sufficient passivation in the acidic lubrication system of biodiesel engines, making it prone to corrosion in the presence of Cl−. Fe amorphous particles exhibit good compatibility with Al-12Si, possessing strong corrosion resistance, excellent passivation ability, and good high-temperature stability. They are a potential reinforcement for enhancing the Al-12Si piston material. Fe amorphous/Al-12Si core-shell structural composites (FACS) were synthesized through ball milling and hot extrusion. The composites’ composition, microstructure, and elemental distribution were characterized by X-ray diffraction, optical microscopy, and EDS spectroscopy. To accelerate the evaluation process, Potentiodynamic polarization and Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy were used to study the electrochemical corrosion behavior. By analyzing the self-corrosion current density (icorr), self-corrosion potential (Ecorr), polarization resistance, inductance, admittance absolute value (Y0), and diffusion coefficient (n), the mechanism of Fe amorphous particle doping in enhancing the corrosion resistance of Al-12Si was discussed. The research results indicate that: The Fe amorphous particles, during ball milling and hot extrusion at 440 °C, do not recrystallize and maintain their good passivation ability. Spherical Fe amorphous particles act as “balls bearings” during hot extrusion, enhancing flowability and promoting the formation of a core-shell structure FACS with uniform composition distribution, high relative density, and low porosity when doping with 2–10% Fe amorphous particles. This prevents the formation of local potential differences, making the potential on the alloy surface more uniform, which helps reduce the risk of galvanic corrosion and improves corrosion resistance. However, when the doping content of Fe amorphous particles reaches 20%, excessive doping particles squeeze and rub against each other during hot extrusion, leading to amorphous agglomeration, low relative density, and high porosity defects in the resulting FACS, which causes uneven potential, increases local potential differences, and reduces corrosion resistance. Compared to Al-12Si, FACS doped with 2–10% Fe amorphous particles shows a decrease in icorr from 254.66 µA/cm2 to 114.98 µA/cm2, and an increase in Ecorr from 766.89 mV to 794.78 mV, indicating a reduced corrosion rate with the doping of an appropriate amount of Fe amorphous particles. As the doping content of Fe amorphous particles increases from 2 to 10%, the polarization resistance increases, indicating improved corrosion resistance; the inductance increases, suggesting that corrosion primarily occurs at the surface; Y0 increases, and n decreases, indicating a reduction in the depth of the corrosion reaction, and the stability of the surface protective oxide film is improved. However, when the doping content of Fe amorphous particles reaches 20%, the opposite effect occurs, and the corrosion resistance of the FACS decreases. Notably, FACS with 10% Fe amorphous particles exhibited the strongest corrosion resistance, making it a potential candidate for biodiesel engine pistons.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As fossil fuels deplete, biomass fuels like biodiesel and bioethanol are becoming viable alternatives due to their environmental benefits1. Biodiesel combustion is not sufficient, the unburned fuel with incomplete combustion products of carbon smoke mixed into the engine lubrication system, easy to pollute the piston skirt and cylinder liner lubrication environment2. Biodiesel is more corrosive than diesel. Impurities like water, methanol, free glycerol, free fatty acids, and catalysts (Na and K) from processing promote the oxidation of esters into highly corrosive fatty acids, producing formic, acetic, propionic, and caproic acids. Additionally, the presence of chlorides in biodiesel leads to the corrosion of Al-Si alloy pistons3,4,5. Although Al-Si alloys can form a thin Al₂O₃ layer that provides some corrosion resistance, this oxide layer is insufficient to protect against the acidic conditions in a biodiesel engine6. Additionally, the potential difference between aluminum and the precipitated phase forms microscopic corrosion cells7, accelerating the corrosion of the Al-Si alloy and causing early piston failure.

Therefore, alloying is frequently employed to improve the corrosion resistance of Al-Si alloys produced through powder metallurgy. For instance, MoO3, with its high polarization resistance and activation energy, can significantly reduce the cathodic reaction of Al alloys8,9, thereby lowering the corrosion rate. However, MoO3 is easily reduced to MoO at high temperatures, creating bonding surface defects and decreasing corrosion performance as temperature increases10. Graphene (GNP) doping resists chloride ion attacks and effectively reduces self-corrosion potential11,12, but it damages the oxide film, creating weak points for corrosive solutions and significantly increasing the risk of galvanic coupling corrosion13,14. B4C-SiC composite reinforcing particles provide an inert physical barrier15, while TiB2 doping blocks corrosion channels and improves resistance to intergranular corrosion16. Although these studies have somewhat enhanced the corrosion resistance of aluminum alloys, the reinforcing particles often have defective bonding surfaces with the substrate, disrupting the continuity of the Al-based oxide film and limiting their applications17. To address these issues, it is essential to find suitable corrosion-resistant reinforcing particles.

Fe amorphous particles and Al-Si alloys can form a strong and effective bonding interface, enhancing their yield strength and thermal compression deformation capacity, among other properties18,19. Doping Fe amorphous particles not only refines the matrix grains20 and forms a stable core-shell structure with high densities21, but their passivation behavior also results in a stable passivation film in acidic and alkaline solutions22, thereby significantly enhancing the corrosion resistance of aluminum matrix composites. Hence, Fe amorphous particles are a preferred choice for improving the corrosion resistance of Al-Si alloys. However, there is limited research on the corrosion resistance of Al-12Si alloy enhanced by Fe amorphous particles in simulated biodiesel engine lubrication systems. The absence of relevant theories hampers the broader adoption and application of biodiesel.

In this study, Fe amorphous particles as the reinforcing phase and employs hot extrusion to fabricate core-shell structured Fe amorphous/Al-12Si piston composites (FACS). The composition, microstructure, and elemental distribution of FACS composites were studied, along with their electrochemical corrosion behavior in a simulated biodiesel engine lubrication system, providing a new approach for the development of novel materials for biodiesel engine pistons.

Experimental procedures

Specimen preparation

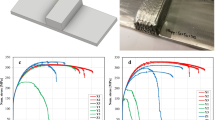

The Al-12Si alloy powder and Fe amorphous powder used in the experiment were both purchased from the Ningbo Institute of Materials Technology and Engineering, China. Tables 1 and 2 present the chemical compositions of Al-12Si alloy powder and Fe amorphous particles prepared using the aerosolization method. Figure 1a illustrates the microscopic morphology of Fe amorphous particles, which are sub-circular and have a particle size of 10–20 μm. X-ray diffraction confirms their complete amorphous structure. The Al-12Si powder exhibited irregular morphology with particle sizes ranging from 5 to 30 μm (Fig. 1b). Fe amorphous particles were incorporated into Al-12Si alloy powder to create x% Fe amorphous/Al-12Si (x = 0, 2, 5, 10, and 20 wt%) mixed powders. The mixing process involved ball milling in a nitrogen atmosphere using the QXQM-2 planetary ball mill, with a ball-to-material ratio of 10:1. Ball milling was carried out for 4 h, followed by a 2-h pause, and this cycle was repeated three times. The uniformly mixed powder underwent continuous molding by hot extrusion at 440 °C to produce rod specimens with a 20 mm diameter, subsequently wire-cut into 10 × 10 × 6 mm block. The specimens were sequentially polished with alumina sandpaper (400#, 800#, 1200#, 2000#, and 5000#) under wet conditions, followed by polishing to a mirror-like surface using SiO2 abrasive paste of W0.05 μm, and finally etched with Keller’s reagent (2.5% HNO3 + 1.5% HCl + 1% HF + 95% H2O).

Corrosion investigations

In order to simulate the acidic and Cl− containing environment of piston use and to accelerate the evaluation of its corrosion resistance, an aqueous solution (pH = 1) formulated with HCl was specially used as a corrosive agent. The polished specimens were degreased ultrasonically in acetone and sealed with epoxy resin, leaving an area of 10 × 10 mm surface for corrosion assessment.

Electrochemical tests were performed at room temperature using a CHI 604E electrochemical analyzer and a classical three-electrode electrochemical cell. A platinum disc was used as an auxiliary electrode, a saturated calomel reference electrode (SCE) as a reference electrode, and a FACS working electrode, with all measured potentials relative to the SCE. The open circuit potential (OCP) was monitored for 3600 s prior to the electrochemical polarization tests. The electrochemical impedance study (EIS) were performed based on the OCP over a frequency range of 0.01 to 100,000 Hz, with an AC perturbation of 10 mV. The Tafel region is typically observed within the OCP ± 0.5 V range. Therefore, based on the OCP (− 0.7 V), potentiostatic polarization were conducted in the range of − 0.2 V to − 1.2 V at a scanning rate of 1.67 mV/s. ChI604E and Zview were used to analyze polarization curves, fitting circuits and Bode/Nyquist curves.

The surfaces of the specimens immersed in the corrosive agent for 168 h were analyzed due to the limited surface corrosion products generated during the electrochemical experiments.

Characterization

The phase composition was analyzed using an Anton Paar XRDynamic500 diffractometer with a scanning speed of 10°/min and a scanning range of 20–80°. The NX30-HK830 optical microscope was used to observe the microstructure, and EDS energy spectroscopy was used to analyze the elemental distribution. The actual density ρc of the specimen was measured in kerosene (density 0.785 g/cc) using Archimedes’ principle and the relative density ω was calculated using Eqs. (1) and (2).

In the Eq. (1) \(W_{\text{Fe}}\) represents the Fe amorphous mass fraction, \(W_{\text{Al-12Si}}\) represents the Al-12Si mass fraction; \(\rho_{\text{Fe}}\) and \(\rho_{\text{Al-12Si}}\) represent the theoretical density of Fe amorphous particles and Al-12Si, respectively.

The corrosion morphology and elemental distribution of corrosion products were analyzed with the HITACHI SU3900 scanning electron microscope and the Oxford Ultim Max40 EDS spectrometer.

Results and discussion

X-ray diffraction

Figure 2 shows the X-ray diffraction results, with the main characteristic peaks of Al-12Si and FACS corresponding to Al and Si. This indicates that no new phases were generated during ball milling and hot extrusion. The diffuse scattering peaks of Fe amorphous particles are clearly present around 43°, this indicates the presence of an amorphous phase in the FACS, confirming that the Fe amorphous particles remained amorphous and were not transformed into crystals during the processes. They remain in the amorphous state, which retains good passivation properties, thereby contributing to the enhanced corrosion resistance of the material.

Microstructure

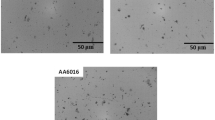

Figure 3 optical micrographs show that Fe amorphous particles with a round, ball-like structure are embedded in the Al-12Si matrix, with evident pores on the matrix surface. The surfaces of FACS samples with Fe amorphous particle doping at 2%, 5%, and 10% are smooth and flat, with rounded, well-packed Fe amorphous particles tightly enclosed within the Al-12Si matrix, displaying no bonding defects such as gaps, thus forming a typical core-shell structure. This suggests good wettability between the Fe amorphous particles and Al-12Si. At a doping content of 20%, however, pores appear on the FACS surface, and the Fe amorphous particles are fragmented, leading to bonding surface defects.

Figure 4 shows the microstructure and elemental distribution, the Al-12Si alloy revealing small amounts of Si crystals and flakes. The dominant elements are Al and Si, with minor amounts of Mg, Cu, Fe, and Mn uniformly distributed (Fig. 4a). In the FACS doped with Fe amorphous particles, the Fe amorphous particles are encapsulated by Al elements in the matrix, forming a unique amorphous/crystalline core-shell structure with Al-12Si. Specifically, in the FACS with 2% and 5% Fe doping, broken Si crystals and sheets are prominently present, and the Fe amorphous particles are larger with a lower dispersion effect (Fig. 4b, c). In contrast, the FACS with 10% Fe doping shows a significant refinement of the Si crystals, a more uniform elemental distribution, and smaller Fe amorphous particle sizes, which often indicates a denser microstructure and better corrosion resistance (Fig. 4d). In the FACS with 20% Fe amorphous particle doping content, the aggregation of Fe amorphous particles is much higher than that in the FACS with 10% Fe amorphous particle doping content (Fig. 4e). This suggests that an excessive amount of Fe amorphous particles leads to agglomeration, which results in an uneven distribution of the cores and reduces the corrosion resistance of the core-shell structure material23.

A suitable amount of Fe amorphous particles act as the core during the extrusion process, serving as “ball bearings” to increase the fluidity of the shell elements (Al-12Si). The uniform distribution of elements, along with the high dispersion of Si crystals and Fe amorphous particles, helps to prevent the formation of local potential differences, making the potential on the alloy surface more uniform, thereby reducing the risk of galvanic corrosion.

Relative density

Table 3 shows the relative density calculations for Al-12Si and FACS, indicating that none of the specimens are fully densified. FACS with 2%, 5%, and 10% Fe amorphous particles have higher relative densities than Al-12Si, while the relative density of FACS decreases at 20% Fe amorphous particle content. These results correspond to the changes in microstructural pores and agglomeration defects observed in Fig. 3a–e. The good fluidity of spherical Fe amorphous particles allows them to fill the tiny pores of the Al-12Si matrix during extrusion molding. However, when the Fe amorphous particle doping content reaches 20%, the excessive doping particles compress and friction against each other, resulting in decreased flowability and the formation of agglomeration defects.

Corrosion performance

Potentiodynamic polarization

After immersing Al-12Si and FACS in the corrosive agent and reaching a stable OPC, the Tafel curves were measured as shown in Fig. 5. The analysis indicates that the FACS potentiodynamic polarization curve resembles that of Al-12Si, with no passivation or over-passivation of Fe amorphous particles observed. This could be due to the highly acidic nature of the corrosive agent, which accelerates the corrosion dissolution reaction, preventing the passivation layer’s influence on the material from being detected24. However, the FACS cathodic potentiodynamic polarization curve with 2–10% Fe amorphous particle doping content is significantly lower than that of the Al-12Si alloy corrosion current density. This indicates that in FACS with an appropriate amount of Fe amorphous particle doping, the passivation ability of Fe amorphous particles effectively suppresses the cathodic hydrogen evolution reaction, reduces stress corrosion, and consequently lowers the corrosion rate.

The cathodic potentiodynamic polarization curves exhibit a distinct Tafel linear region, indicating activation-controlled reactions at the working electrode. Thus, Tafel linear extrapolation25 was used to fit the potentiodynamic polarization curves, as shown in Table 4, which includes self-corrosion current density (icorr) and self-corrosion potential (Ecorr). As the Fe amorphous doping content increased from 2 to 10%, the icorr of FACS decreased from 246.59 µA/cm2 to 114.98 µA/cm2, both lower than that of Al-12Si alloy (icorr 254.66 µA/cm2). Additionally, the Ecorr of FACS increased from 779.41 mV to 794.78 mV, both higher than that of Al-12Si alloy. Lower icorr and higher Ecorr correspond to a lower corrosion rate, indicating that Fe amorphous particles effectively enhance the corrosion resistance of Al-12Si alloy. On one hand, the Fe amorphous particles facilitate the formation of a passive film, and both the Fe amorphous particles and their passive layer act as an inert barrier, which is beneficial for enhancing corrosion resistance26. On the other hand, the higher activation energy of Fe amorphous particles compared to Al-12Si, which hinders electron transfer and reduces electrochemical kinetics19. Furthermore, Fe amorphous particles replace a portion of the Si and act as cathodes, further reducing the electron transfer rate and decreasing the cathodic reaction. As a result, the self-corrosion current density decreases, and the self-corrosion potential increases, which corresponds to a reduction in the corrosion rate. However, when the Fe amorphous particles doping content increased to 20%, the formation of agglomeration defects and increased porosity led to a higher specific surface area exposed to the corrosive agent, exacerbating the corrosion rate. Consequently, the icorr rose to 344.34 µA/cm2, and the Ecorr dropped to 761.80 mV, decreasing the corrosion resistance of the Al-12Si alloy.

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy

The Nyquist plots of Al-12Si and FACS electrochemical impedance spectroscopy shown in Fig. 6 feature capacitive loops at high and medium frequencies and inductive loops at low frequencies, indicating two corrosion processes. The rough surface of the aluminum electrode creates a dispersion effect27, resulting in an approximately elliptical capacitive loop rather than a complete semicircle. A larger semicircular capacitive loop resistance suggests that, during corrosion, aluminum loses electrons and transforms into Al3+ within the double electric layer at the alloy-solution interface. The capacitive loop provides charge transfer impedance, and its diameter represents the polarization resistance; greater polarization resistance implies stronger impedance to charge transfer and better corrosion resistance16. The inductive loop at low frequencies is associated with the corrosion reaction and oxide film at the metal/solution interface. Water molecules and Cl− ions interact with the metal surface, causing instability due to Cl− penetration and adsorption, leading to the formation of an inductive loop from the impedance of transient reaction intermediates28.

The electrochemical impedance spectroscopy parameters obtained from fitting the Nyquist plot using the equivalent circuit shown in Fig. 6 are listed in Table 5. The circuit includes components such as solution resistance (Rµ), charge transfer resistance (Rct), inductive resistance (RL), inductance (L), and constant phase element (CPE), representing the capacitance between electrodes, used to replace ideal capacitors. According to Table 5, as the doping content of Fe amorphous particles in FACS increases from 2 to 10%, the polarization resistance (Rct) increases from 548.5 Ω·cm2 to 1268 Ω·cm2, higher than that of Al-12Si at 353.2 Ω·cm2. However, when the Fe amorphous particles doping content reaches 20%, the polarization resistance of FACS decreases to 297.3 Ω·cm2. This indicates that doping with 2–10% Fe amorphous particles enhances the polarization resistance of Al-12Si. The higher inductance (L) values in Fe amorphous particle-doped FACS compared to Al-12Si suggest that corrosion predominantly occurs on the surface rather than deep within the alloy6, implying a smaller coverage of corrosion products on the surface of FACS than Al-12Si. The parameters of the CPE include Admittance Absolute Value (Y0) and diffusion coefficient (n). With Fe amorphous particles doping content increasing from 2 to 10%, Y0 increases and n decreases for FACS, indicating improved surface capacitive behavior and better stability of the original surface protective oxide film. However, when Fe amorphous particles doping content reaches 20%, Y0 decreases and n increases, suggesting deteriorated surface capacitive behavior and reduced stability of the oxide film.

The changes in the electrochemical impedance spectroscopy parameters are attributed to the effect of Fe amorphous particle doping. The strong corrosion resistance and high relative density due to moderate doping reduced the reaction area between Al and HCl and prevented the corrosive agent from penetrating the alloy’s depth, thus mitigating corrosion. Additionally, this doping improved the stability of the oxide film on the surface, effectively enhancing the corrosion resistance of the Al-12Si alloy.

Corrosion pattern

Figure 7 shows the corrosion surface morphology after 168 h of immersion in the corrosive agent, indicating that intergranular corrosion, pitting, stress corrosion, and exfoliation corrosion occurred in both Al-12Si and FACS. At higher icorr, the Al-12Si alloy surface was severely eroded, forming many fine cavities (Fig. 7a). This erosion likely results from the anodic dissolution of the matrix around the grains at the grain boundaries29, which then develops into grain boundary corrosion. This corrosion gradually propagates to deeper levels, forming large and deep surface pits. Fine particles formed by corrosion products adsorb on the surface, and intergranular corrosion creates irregular pits surrounding the aluminum grains, known as pitting. Further corrosion, involving Cl− and the Al matrix, produces a hydrogen precipitation reaction causing stress corrosion cracking. Intergranular corrosion and pitting connect to form a network, leading to surface layer spalling, which exposes new matrix areas to react with HCl, causing transverse and longitudinal expansion of pits, ultimately leading to larger pits.

The surface of 2% Fe amorphous particle-doped FACS shows wide and deep cracks, covered with large cracked flakes, Exfoliation corrosion is lighter than Al-12Si (Fig. 7b), indicating mainly grain boundary and pitting corrosion. The 5% Fe amorphous particle-doped FACS surface has narrow, shallow cracks, with large, thin cracked flakes and shallow pits, indicating limited stress corrosion penetration (Fig. 7b). The 10% Fe amorphous particle-doped FACS surface is the flattest, with light grain-boundary corrosion crevices and a few pitting pits (Fig. 7d), showing reduced corrosion. However, the 20% Fe amorphous particle-doped FACS surface resembles that of Al-12Si alloy, with grain boundary corrosion, pitting, and exfoliation corrosion, along with agglomerated Fe amorphous particles and a small amount of white flocculent corrosion products (Fig. 7e).

The reason for this is that in the FACS with 2–10% Fe amorphous particle doping, the dispersed Fe amorphous particles form a core-shell structure with Al-12Si, improving the relative density and reducing the intergranular corrosion pathways caused by pores and other defects. On the other hand, the corrosion-resistant Fe amorphous particles, with their passivation effect, reduce local voltage differences, generating a physical barrier to corrosion and hindering the penetration of corrosive agents. This enhances the ability of Al-12Si alloys to resist intergranular corrosion, stress corrosion, and exfoliation corrosion. The Al-12Si alloy surface is distributed with pores, which provide channels for corrosive media to invade the metal substrate. Corrosive media can easily penetrate through these pores into the material, forming localized electrochemical corrosion regions. Pores not only increase the exposed surface area of the substrate but also potentially lead to the occurrence of intergranular corrosion, thereby promoting pitting formation and further accelerating the corrosion process. When the doping content of Fe amorphous particles reaches 20%, the amorphous agglomeration leads to uneven microstructure and local structural defects, which may become preferential sites for corrosion, triggering intergranular corrosion. Meanwhile, the agglomeration phenomenon causes uneven potential, increasing local potential differences and forming highly reactive areas, which in turn promotes galvanic corrosion. Therefore, the corrosion resistance of Al-12Si alloys and FACS with 20% Fe amorphous particle doping is relatively weak.

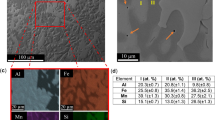

Corrosion product

Figure 8 presents the SEM-EDS analysis results of the corrosion products after immersion in the corrosive agent for 168 h. Al-12Si surfaces exposed to air typically form a 0.01–0.1 μm thick Al2O3 passivation film, which is highly susceptible to corrosion in aggressive environments, losing its protective effect. During the electrochemical corrosion process, Si acts as the cathode and remains protected. When active elements and unstable phases dissolve, they create deep corrosion channels in the alloy. The reaction 2Al + 6HCl → 2AlCl3 + 6H2 occurs as HCl wraps around Al. Further corrosion forms a mixture of Al-Si fine particles (Fig. 8a No. 2, b No. 1, c No. 3, d No. 2), due to significant Al dissolution and the exposure of cathodic Si. The FACS with 10% Fe amorphous particles shows significantly fewer fine particles compared to Al-12Si and FACS with 20% Fe amorphous particles, indicating a lower degree of corrosion. As Al continues to dissolve and flake off, only large Si particles remain (Fig. 8a No. 3, c No. 2, e No. 4). In FACS, Fe amorphous particles react with Cl− through 2Fe + 6HCl → 2FeCl3 + 3H2, resulting in white corrosion products on the Fe amorphous surface (Fig. 8b No. 2, d No. 4, e No. 3). The corrosion damage of Fe amorphous particles is less severe than that of Al. In 10% Fe amorphous particle-doped FACS, most Fe amorphous particles remain unaffected by corrosion (Fig. 8b No. 1).

Additionally, oxygen-rich products, identified as Al hydroxides, were found in FACS (Fig. 8b No. 3, c No. 1, d No.3, e No. 1). In aluminum alloys, free electrons from the primary battery system cause the cathode to electrolyze water, producing hydroxide ions. These ions react with Al3+ to form insoluble Al(OH)330, creating a passivation layer that blocks Cl− and acts as a barrier to the corrosive electrolyte13,31. This phenomenon was not observed in Al-12Si alloy, suggesting that Fe amorphous particles facilitate passivation layer formation. Furthermore, Fe amorphous particles contribute to corrosion resistance by acting as a “passivation layer” themselves, blocking deep Cl− attacks and protecting the matrix, thus enhancing the corrosion resistance of the Al-12Si alloy.

Conclusion

-

(1)

Spherical Fe amorphous particles act as ‘ball bearings’ during the hot extrusion process, enhancing flowability. The doping of 2–10% Fe amorphous particles results in a core-shell structure FACS with uniform composition distribution, high relative density, and low porosity. This structure helps to avoid the formation of local potential differences, making the surface potential of the alloy more uniform, which in turn reduces the risk of galvanic corrosion and improves corrosion resistance. However, when the doping level of Fe amorphous particles reaches 20%, excessive particles exert pressure and friction on each other, leading to amorphous particle agglomeration, lower density, and higher porosity. These defects cause uneven potential distribution, increasing local potential differences and reducing corrosion resistance.

-

(2)

With the incorporation of 2–10% Fe amorphous particles, the self-corrosion current density (icorr) of the FACS decreases from 254.66 µA/cm2 to 114.98 µA/cm2, and the self-corrosion potential (Ecorr) increases from 766.89 mV to 794.78 mV compared to the Al-12Si alloy, indicating a reduction in corrosion rate and significantly enhanced corrosion resistance. However, at 20% Fe amorphous particles doping, this trend reverses, with icorr increasing and Ecorr decreasing, indicating a decline in corrosion resistance.

-

(3)

Alloys doped with 2–10% Fe amorphous particles show higher polarization resistance, indicating improved corrosion resistance. The increase in inductance suggests that corrosion mainly occurs at the surface. The admittance absolute value (Y0) increases, and the diffusion coefficient (n) decreases, indicating an improvement in the stability of the surface protective oxide film. However, when the Fe amorphous particle doping content increases to 20%, the opposite trend is observed, with the corrosion resistance of the FACS decreasing instead of increasing.

-

(4)

The overall enhancement in corrosion resistance is attributed to the strong passivation ability of the Fe amorphous particles and the formation of a dense, uniform core-shell structure at moderate Fe doping levels. Among all tested samples, the 10% Fe amorphous particles-doped alloy exhibits the best performance, making it a promising candidate for biodiesel engine pistons.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Devarajan, Y., Beemkumar, N., Ganesan, S. & Arunkumar, T. An experimental study on the influence of an oxygenated additive in diesel engine fuelled with neat papaya seed biodiesel/diesel blends. Fuel 268, 117254 (2020).

Temizer, İ. The combustion analysıs and wear effect of biodiesel fuel used in a diesel engine. Fuel 270, 117571 (2020).

Maawa, W. N., Mamat, R., Najafi, G. & De Goey, L. P. H. Performance, combustion, and emission characteristics of a CI engine fueled with emulsified diesel-biodiesel blends at different water contents. Fuel 267, 117265 (2020).

Song, G. L. & Liu, M. Corrosion and electrochemical evaluation of an Al–Si–Cu aluminum alloy in ethanol solutions. Corros. Sci. 72, 73–81 (2013).

Haseeb, A. S. M. A., Fazal, M. A., Jahirul, M. I. & Masjuki, H. H. Compatibility of automotive materials in biodiesel: a review. Fuel 90, 922–931 (2011).

Peng, Y. et al. Electrochemical corrosion behavior of 6061 Al alloy under high rotating speed submerged friction stir processing. Corros. Sci. 215, 111029 (2023).

Rubben, T., Revilla, R. I. & De Graeve, I. Influence of heat treatments on the corrosion mechanism of additive manufactured AlSi10Mg. Corros. Sci. 147, 406–415 (2019).

Almomani, M. A., Tyfour, W. R. & Nemrat, M. H. Effect of silicon carbide addition on the corrosion behavior of powder metallurgy Cu30Zn brass in a 3.5 wt% NaCl solution. J. Alloys Compd. 679, 104–114 (2016).

Zakaria, H. M. Microstructural and corrosion behavior of Al/SiC metal matrix composites. Ain Shams Eng. J. 5, 831–838 (2014).

Stalin, B., Sudha, G. T., Kailasanathan, C. & Ravichandran, M. Effect of MoO3 ceramic oxide reinforcement particulates on the microstructure and corrosion behaviour of Al alloy composites processed by P/M route. Mater. Today Commun. 25, 101655 (2020).

Xie, Y. et al. Homogeneously dispersed graphene nanoplatelets as long-term corrosion inhibitors for aluminum matrix composites. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 32161–32174 (2021).

Akçamlı, N., Şenyurt, B., Gökçe, H. & Ağaoğulları, D. Powder metallurgical fabrication of graphene reinforced near-eutectic Al-Si matrix composites: Microstructural, mechanical and electrochemical characterization. Eng. Sci. Technol. 31, 101052 (2022).

Rashad, M. et al. Investigation on microstructural, mechanical and electrochemical properties of aluminum composites reinforced with graphene nanoplatelets. Prog Nat. Sci. Mater. Int. 25, 460–470 (2015).

Turan, M. E. et al. Effects of carbonaceous reinforcements on microstructure and corrosion properties of magnesium matrix composites. Mater. Chem. Phys. 218, 182–188 (2018).

Karabacak, A. H., Çanakçı, A., Erdemir, F., Özkaya, S. & Çelebi, M. Corrosion and mechanical properties of novel AA2024 matrix hybrid nanocomposites reinforced with B4C and SiC particles. Silicon 14, 8567–8579 (2022).

Chen, L. et al. Investigation on corrosion behaviors and mechanical properties of TiB2/7075Al composites with various particle contents. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 23, 2911–2923 (2023).

Sun, H. H., Chen, D., Li, X. F., Ma, N. H. & Wang, H. W. Electrochemical corrosion behavior of Al–Si alloy composites reinforced with in situ TiB2 particulate. Mater. Corros. 60, 419–423 (2009).

Wang, Z., Scudino, S., Stoica, M., Zhang, W. & Eckert, J. Al-based matrix composites reinforced with short Fe-based metallic glassy fiber. J. Alloys Compd. 651, 170–175 (2015).

Yang, H., Wang, Y., Wang, X., Cen, Q. & Yu, X. Strengthening mechanism and thermal deformation behavior of Al-12Si/Fe piston composite. Mater. Res. Express. 7, 016596 (2020).

Guan, H. D. et al. Fe-based metallic glass particles reinforced Al-7075 matrix composites prepared by spark plasma sintering. Adv. Powder Technol. 31, 3500–3506 (2020).

Guan, H. D. et al. Aluminum matrix composites reinforced with metallic glass particles with core-shell structure. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 771, 138630 (2020).

Huaixiao, X. I. A., Qingjun, C. & Chengjie, W. Evaluating corrosion resistances of Fe-based amorphous alloys by YCr/Mo values. J. Rare Earths. 35, 406–411 (2017).

Qian, L. et al. Amorphous thickness-dependent strengthening–softening transition in crystalline–amorphous nanocomposites. Nano Lett. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.3c03848 (2023).

Aydın, F. A review of recent developments in the corrosion performance of aluminium matrix composites. J. Alloys Compd. 949, 169508 (2023).

AbdElRhiem, E. et al. Corrosion suppression and strengthening of the Al-10Zn alloy by adding silica nanorods. Sci. Rep. 14, 15644 (2024).

Li, J. et al. Improved corrosion resistance of novel Fe-based amorphous alloys. Mater. Des. 95, 225–230 (2016).

Li, X., Deng, S., Lin, T., Xie, X. & Du, G. Cassava starch-sodium allylsulfonate-acryl amide graft copolymer as an effective inhibitor of aluminum corrosion in HCl solution. J. Taiwan. Inst. Chem. Eng. 86, 252–269 (2018).

Gobara, M., Shamekh, M. & Akid, R. Improving the corrosion resistance of AZ91D magnesium alloy through reinforcement with titanium carbides and borides. J. Magn. Alloys 3, 112–120 (2015).

Ngai, S. et al. Saltwater corrosion behavior of cold sprayed AA7075 aluminum alloy coatings. Corros. Sci. 130, 231–240 (2018).

Li, Z. et al. First-principles study on surface corrosion of 6082 aluminum alloy in H+ and Cl– medium. J. Mol. Struct. 1294, 136570 (2023).

Domínguez-Crespo, M. A., Brachetti-Sibaja, S. B., Torres-Huerta, A. M. & De La Cruz-Hernández, W. Rare earth conversion coatings grown on AA6061 aluminum alloys. Corrosion studies. J. Mex Chem. Soc. 58, 393–410 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Yunnan Province Agricultural Basic Research Joint Special Key Project of China (Grant No. 202301BD070001-012) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No.51301144), the authors gratefully acknowledge their financial support. The authors also wish to thank the Key Laboratory of Forest Disaster Warning and Control of Yunnan Province for their valuable support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, investigation, visualization, writing-original draft, Y. W.; supervision, methodology, visualization, Z. L.; data curation, formal analysis, investigation, C. L., D. Z. and C. L.; writing - review & editing, funding acquisition, Y. W.; all authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., Lin, Z., Liu, C. et al. Corrosion behavior of Fe amorphous/Al-12Si piston composites with core-shell structure. Sci Rep 15, 2773 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87365-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87365-1

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Comparative assessment of the mechanical, tribological, and corrosion properties of Al/SiC/Al2O3 and Al/SiC/TiO2 hybrid composites

Discover Applied Sciences (2025)