Abstract

This cross-sectional study aimed to explore the association between tinnitus and menstrual cycle disorders in premenopausal women. A total of 558 participants completed a comprehensive questionnaire covering demographics, tinnitus, and gynecological/obstetric history. The analysis investigated the correlation between tinnitus and various menstrual disorders, including dysmenorrhea (primary, secondary, or premenstrual syndrome), as well as different menstrual cycle patterns (regular, hypomenorrhea, menorrhagia, oligomenorrhea, or polymenorrhea). Among the participants, 33% reported experiencing tinnitus, with 74.4% experiencing dysmenorrhea. The most prevalent pathological menstrual pattern was menorrhagia (20%), followed by hypomenorrhea (11.11%). The results revealed a significant increase in tinnitus among premenopausal women with secondary dysmenorrhea (p value < 0.001) or menorrhagia (p value < 0.002) compared with those without tinnitus. Adjustment for confounding variables such as age, income, and psychological health problems did not alter the significant correlations between tinnitus and secondary dysmenorrhea and menorrhagia. Further research is needed to elucidate the nature of this relationship and its underlying mechanisms. Both tinnitus and menstrual disorders can have substantial impacts on the well-being of affected women, and a deeper understanding of these issues could pave the way for improvements in their health care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tinnitus is a prevalent health issue affecting approximately 14% of the global population, with 2% experiencing severe symptoms1. While research indicates similar prevalences among males and females, females tend to experience a greater degree of handicap2. The literature suggests that tinnitus may be linked to menstrual cycle-related conditions, including pregnancy and menstrual cycle disorders3,4. Dysmenorrhea, followed by premenstrual syndrome, is the most prevalent menstrual cycle disorder5,6,7. Dysmenorrhea, defined as painful menstruation, can be primary or secondary. Unlike secondary dysmenorrhea, primary dysmenorrhea is characterized by the absence of pelvic pathology and is the most common gynecological disorder among premenopausal women8. Both dysmenorrhea and tinnitus are common and negatively impact premenopausal women’s health and well-being9,10; however, their associations are poorly understood.

Risk factors for both tinnitus and menstrual cycle disorders seem to be closely related. Table 1 summarizes the identified common risk factors for both conditions. Most of these are modifiable risk factors. Therefore, investigating their relationship is imperative. Yu et al.3 explored the association between an irregular menstrual cycle and the odds of tinnitus among 4633 premenopausal Korean women3. The participants were screened for tinnitus and menstrual cycle irregularity. The participants’ menstrual cycle characteristics were determined by asking about the duration of their cycles. Those confirming regular cycles were categorized accordingly, whereas those reporting irregular cycles were asked about the duration between menstruations (regular versus up to 3 months or longer). They identified a notable correlation between the presence of tinnitus and irregularities in the menstrual cycle. The likelihood of experiencing tinnitus increased with increasing intervals between menstruations.

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, the research of Yu et al.3 is the first to shed light on the link between tinnitus and menstrual cycle disorders. One limitation of their study was the classification of menstrual cycle patterns solely based on cycle duration, which was not inclusive of all irregularity types (e.g., polymenorrhea). In addition, they did not explore whether there was a correlation between tinnitus and other categories of menstrual cycle disorders, including primary and secondary dysmenorrhea, menorrhagia, hypomenorrhea, polymenorrhea, and premenstrual syndrome. They also suggested that future research should employ more detailed parameters to classify menstrual cycle irregularities.

This prospective cross-sectional study aimed to investigate the link between tinnitus and menstrual cycle irregularities further in depth by exploring the associations between tinnitus and various types of menstrual cycle disorders (dysmenorrhea, menorrhagia, hypomenorrhea, polymenorrhea and premenstrual syndrome) among premenopausal women. We hypothesized that there is a correlation between tinnitus and irregularities in the menstrual cycle among premenopausal women. In addition, we hypothesized that the nature of this correlation varies on the basis of the specific types of menstrual cycle irregularities.

The widespread prevalence of both tinnitus and menstrual cycle disorders significantly impacts the physical and mental health of women9,10. Recognizing the importance of reducing the burden posed by these health problems, it is necessary to understand their associations, modify their risks, and develop improved health care plans for affected women.

Results

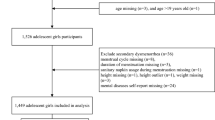

The STROBE checklist for cross-sectional studies was used to ensure quality reporting38. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. Seven hundred and fifteen individuals participated in a survey asking about demographics, general health, tinnitus, and gynecological and obstetrics history (the specific details about the questions are provided in the methodology section). Following the application of the inclusion and exclusion criteria, the data from 558 participants were included in the subsequent analysis. A total of 157 participants were excluded for the following reasons: 5 were under 18 years old, 24 were pregnant, 47 were breastfeeding, and 81 had reached menopause.

Demographics

The participants’ characteristics are available in Table 2.

Attributes of the study participants based on tinnitus presence

Tinnitus was reported in 33% (184) of the participants. Table 3 shows the characteristics of the study participants according to the presence/absence of tinnitus. Compared with their counterparts without tinnitus, the participants who experienced tinnitus were older, had increased rates of marriage and parity, and had lower income levels. Moreover, those who reported tinnitus had several abnormal general health issues, including increased weight, dyslipidemia, insomnia, psychological health problems, vitamin D deficiency, tension and migraine headaches. There were no differences according to oral contraceptive use, education level, occupation, smoking, fiber intake, regular exercise or hypothyroidism between those with tinnitus and those without tinnitus.

Attributes of the study participants based on menstrual cycle characteristics

Figure 1 shows the distribution of participants according to their experience of pain related to menstruation. A total of 74.4% of the participants had dysmenorrhea. A total of 6.5% reported experiencing pain only before menstruation as part of their premenstrual syndrome.

Among the entire sample, 53.6% indicated that they experienced typical menstrual cycle characteristics, whereas 46.4% noted abnormalities in either blood flow or the regularity of their menstrual cycle; the most prevalent pathological menstrual pattern was menorrhagia (20%), followed by hypomenorrhea (11.11%). Figure 2 shows the distribution of various abnormal menstrual patterns in 46.5% of the participants.

The correlation between tinnitus and menstrual cycle attributes

Figure 3 shows the tinnitus prevalence among the categories associated with experienced pain related to menstruation. The correlations between tinnitus and pain, including all types of tinnitus (primary, secondary, and premenstrual syndrome), were not significant (p value = 0.105). However, between-group analysis (primary, secondary, and premenstrual syndrome) revealed a significant association between tinnitus and secondary dysmenorrhea (p value < 0.001). Figure 4 illustrates tinnitus in relation to various menstrual cycle patterns. A significant correlation was found between tinnitus and menorrhagia (p value < 0.002).

After adjustment for potential confounding factors, including age, marital status, parity, income, smoking status, body mass index and psychological health problems, tension headache, migraine, vitamin D deficiency, insomnia, and dyslipidemia, the associations between tinnitus and secondary dysmenorrhea as well as menorrhagia persisted.

Discussion

This study explored the relationship between tinnitus and menstrual cycle disorders in premenopausal women. These findings indicate that women experiencing menstrual cycle problems are more likely to report tinnitus, which aligns with previous research3. A key contribution of this study is the identification of specific menstrual disorders, such as secondary dysmenorrhea and menorrhagia, that are particularly associated with a greater likelihood of tinnitus. However, the underlying mechanisms linking these conditions remain unclear and require further investigation. Exploring the plausible theories linking tinnitus and menstrual disorders could lead to several considerations. First, psychological factors, particularly depression and stress, emerge as potential contributors. Depression, one of the most common mental illnesses in adults, significantly influences the perception and severity of physical symptoms39. Additionally, it is closely tied to reproductive health40, affecting menstruation, fertility41, and menopause42. Consequently, women with depression often experience poorer reproductive health outcomes than those without depression43,44.

On the other hand, chronic pain from secondary dysmenorrhea and the physical and emotional burden of menorrhagia can lead to increased stress, anxiety, and depressive symptoms40,45. These psychological conditions are well-documented risk factors for tinnitus46. In addition, the persistent presence of tinnitus can exacerbate psychological distress, creating a feedback loop that intensifies the burden of all three conditions47,48. This interconnected relationship between psychosocial health and menstrual health and tinnitus emphasizes the importance of addressing mental health as a key component in managing menstrual disorders and improving the overall quality of life of premenopausal women. Nevertheless, psychological factors alone may not explain the association between tinnitus and menstrual disorders, as when we accounted for this confounding factor, the correlation between tinnitus and secondary dysmenorrhea remained independent.

Second, various health problems could be involved. Conditions such as vitamin D deficiency, hypothyroidism, insomnia and obesity are common factors for both tinnitus and dysmenorrhea, as shown in Table 1. The data analysis for tinnitus among the participants suggested that it was associated with vitamin D deficiency, insomnia and obesity but was not associated with hypothyroidism. Nevertheless, controlling for confounding factors such as vitamin D deficiency, insomnia and obesity revealed that there is still a correlation between tinnitus and secondary dysmenorrhea. Moreover, it is essential to note that known common risk factors (elaborated in Table 1), such as vitamin D deficiency and hypothyroidism, predominantly contribute to primary dysmenorrhea, not secondary dysmenorrhea29,32,33,34. Overall, it is difficult to make bold statements about the link between secondary dysmenorrhea and these two conditions because most studies have investigated a single pathology under the umbrella of secondary dysmenorrhea, such as endometriosis. There is a lack of research, such as ours, investigating secondary dysmenorrhea as a category regardless of the pathologies involved.

Third, modifiable lifestyle factors, such as smoking, exercise and eating habits, have been proposed as risk factors in previous research (Table 1). Unexpectedly, these three factors were not associated with increased tinnitus risk among our participants. Our results concerning smoking in particular contradict those of Yu et al.3, who reported that smoking increased the odds of experiencing tinnitus. Nevertheless, the link between tinnitus and menstrual cycle irregularities persisted after Yu et al.3 adjusted for smoking as a confounding factor.

Finally, we suggest that there could be a multifactorial relationship between tinnitus and secondary dysmenorrhea that may be influenced by physiological and/or pathological processes, including hormonal changes. Hormonal imbalances and stress, often induced by conditions such as endometriosis and uterine fibroids, can contribute to both ailments49,50. Some individuals may experience exacerbation of tinnitus symptoms due to stress and hormonal fluctuations. Moreover, women with secondary dysmenorrhea may receive hormonal or psychiatric medications to alleviate discomfort or address underlying illnesses. This constitutes research material for future projects.

Secondary dysmenorrhea could imply the presence of an underlying pathologic process such as endometriosis, adenomyosis, or leiomyomas or could be related to hormonal changes induced by hormonal intrauterine contraception devices51. Most of these factors can cause menorrhagia and consequently lead to iron deficiency anemia, which is known to trigger hearing problems and tinnitus52,53. Our findings indicate that menorrhagia may be a risk factor for tinnitus in premenopausal women. A total of 27.7% of women who experienced menorrhagia reported tinnitus, whereas 24.5% of those who did not have menorrhagia but had other irregularities reported tinnitus. Future research could investigate the prevalence of iron deficiency in premenopausal women who experience menorrhagia and correlate it with tinnitus. This investigation can help clarify the role of iron supplements in the management of tinnitus among premenopausal women with secondary dysmenorrhea. Iron deficiency treatment is especially cost-effective and improves tinnitus outcomes54.

Clinically, this correlation implies that medical professionals should consider gynecological issues when having consultations for tinnitus. Tinnitus in premenopausal women can be controlled or alleviated if patients are managed for menstrual cycle problems. The need for a multidisciplinary approach to patient treatment, where gynecologists and tinnitus specialists work together to address the complex interactions between reproductive health and auditory function, is also highlighted by this research.

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study to provide a detailed analysis of menstrual cycle irregularities in relation to tinnitus. Previous research on the link between tinnitus and menstrual cycle irregularities by Yu et al.3 did not investigate in depth the various types of irregularities or types of dysmenorrhea and encouraged future research to do so. This study identified all known types of irregularities and dysmenorrhea subtypes and investigated their correlation with tinnitus and revealed that tinnitus is linked to pathological (secondary) rather than nonpathological (primary) dysmenorrhea.

The results of this research can be generalized for several reasons. First, our findings are cross-validated when they are compared with the results of Yu et al.3, who investigated premenopausal women in different settings, with different methodologies and among different populations (Korean), cultures and environments. Second, our sample had an adequate size to ensure that it was representative of the population, enhancing the external validity and generalizability of our findings. Finally, this study had clear inclusion and exclusion criteria and included premenopausal women with various demographic characteristics, including age, marital and parity status, income, education and employment. All of these factors increase the validity and generalizability of the results, as it can be considered a representative sample of premenopausal women.

Limitations: The cross-sectional nature of this study prevents an in-depth understanding of the causation, direction and temporal relationship between secondary dysmenorrhea and tinnitus. Longitudinal research could assist in understanding this link by studying the relationship at multiple time points to capture changes in symptoms over the menstrual cycle and possibly over years throughout women’s reproductive period. Some women with tinnitus may report changes in their symptoms during different phases of the menstrual cycle. For example, some may experience an increase in tinnitus symptoms in the premenstrual phase, whereas others may notice changes during ovulation or menstruation. These observations may assist in identifying a possible link between tinnitus and hormonal changes.

This study also used self-reported data, which has the potential to introduce various forms of bias, including memory bias55. To minimize this risk, the participants were asked about tinnitus during a specific recent period of time (the past year). This study did not assess anemia directly, which may be a contributing factor to the observed relationship between tinnitus and menorrhagia. Future studies should incorporate laboratory evaluations, including hemoglobin levels, ferritin, and other anemia-related parameters, to better understand the potential role of anemia in tinnitus occurrence among premenopausal women. To improve the validity of the results, future studies should include quantified measures of tinnitus intensity and monthly bleeding patterns as well as laboratory measurements of the factors that could be involved, including serum vitamin D and ferritin levels.

Conclusion

This study is the first to suggest that there is a link between dysmenorrhea, secondary dysmenorrhea and menorrhagia in particular, and tinnitus among premenopausal women. The nature of this relationship and its processes has yet to be explored in future research. Both conditions can impact the well-being of affected women, and further understanding of these issues can open channels for improvements in their health care.

Materials and methods

This research was approved by the ethics committee of the University of Jordan (964/2023/67) and the Institutional Review Board of Jordan University Hospital (10/2023/25110). This research complied with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Study design

Prospective cross-sectional study.

Data source and participants

The participants were recruited via various methods. First, the study was advertised on one social media platform (Facebook). Second, many participants were approached personally by the authors, mainly at the University of Jordan campus or Jordan University Hospital. Finally, snowballing recruitment was also utilized, whereby the participants were asked to assist researchers in identifying other potential subjects. The inclusion criterion was premenopausal women aged 18 years or older, whereas the exclusion criteria were pregnant, nursing, and menopausal women. The data were collected between October 2022 and January 2023.

Sample size

The sample size for this study was calculated using Epiinfo@Software (from the CDC), with a confidence level of 95%. Using data from the latest statistics by the National Department of Statistics (DOS), the estimated sample size required was 384. The study sample exceeded this number and gathered data from 558 participants to obtain a representative sample size, enhancing external validity and allowing for meaningful subgroup analyses, ensuring the generalizability and applicability of our findings to the broader population.

Study tool

The survey asked about demographics, tinnitus, and gynecological and obstetrics history, with specific details about the questions provided below.

The presence of tinnitus was assessed using a question adopted from prior research: “Have you experienced tinnitus within the past year (ringing, buzzing, roaring, hissing)?”3. Menstrual cycle characteristics were assessed by asking the participants to respond to the following question: “Do you experience pain during or before menstruation?” If participants answered “yes”, they were required to answer the following question: “When are you suffering from pain related to menstruation?” We classified dysmenorrhea into 2 categories on the basis of the participants’ responses. The first was primary dysmenorrhea if the participants chose “pain before or during the first 2 days of menstruation”; the second was, secondary dysmenorrhea if the participants chose one of these: “pain throughout menstruation” or “pain throughout menstruation and during the week before the onset of menstruation”. We also asked about premenopausal syndrome, and it was identified if the participant chose “pain before menstruation only”.

Menstrual cycle irregularities were then divided into five categories on the basis of the participants’ answers to the following question: “How do you describe your menstrual cycle?” (1) Menorrhagia if women chose a “heavy regular cycle with blood clots”; (2) Polymenorrhea if women chose “frequent cycle: the time elapsed between two consecutive menstruation events is less than 21 days”; (3) Oligomenorrhea if women chose “infrequent cycle: the time elapsed between two consecutive menstruation events is more than 35 days”; (4) Regular cycle if women chose “regular cycle and average regular bleeding”; and (5) Hypomenorrhea if women chose a “regular cycle but little bleeding”.

The questionnaire also included questions addressing the various covariates. Information about participants’ sociodemographics, lifestyle and general health was obtained. The questionnaire asked about education, occupation, income, marital status, parity, smoking, weight and height, physical activity, diet and a group of medical conditions (hypothyroidism, vitamin D deficiency, insomnia, dyslipidemia, depression, anxiety, tension headache and migraine).

Statistical analysis

The data were entered into and analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS), version 25 for Mac. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the data, with continuous variables expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (STD) and range. Categorical data are expressed as counts and percentages. Numeric data were assessed for normality via the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, histograms and Q-Q plots. The assumptions for using parametric statistics were satisfactory when the Levene test was used for equal variances. Analysis was performed before and after adjusting for possible confounding factors (age, marital status, parity, income, smoking status, body mass index (BMI), psychological health problems, tension headache, migraine, vitamin D deficiency, insomnia and dyslipidemia). Continuous data were compared between groups using independent samples t tests and ANOVA. Categorical data were analyzed via the chi-square test. A P value < 0.05 was assigned as α.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Change history

07 May 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99049-x

References

Jarach, C. M. et al. Global prevalence and incidence of tinnitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Neurol. (2022).

Yuan, H. et al. Correlation between clinical characteristics and tinnitus severity in tinnitus patients of different sexes: An analytic retrospective study. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 280, 167–173 (2023).

Yu, J. N. et al. Association between menstrual cycle irregularity and tinnitus: A nationwide population-based study. Sci. Rep. 9, 14038 (2019).

da Silva Schmidt, P. M., da Trindade Flores, F., Rossi, A. G. & da Silveira, A. F. Hearing and vestibular complaints during pregnancy. Braz. J. Otorhinolaryngol. 76, 29–33 (2010).

Rafique, N. & Al-Sheikh, M. H. Prevalence of menstrual problems and their association with psychological stress in young female students studying health sciences. Saudi Med. J. 39, 67 (2018).

Abdelmoty, H. I. et al. Menstrual patterns and disorders among secondary school adolescents in Egypt. A cross-sectional survey. BMC Women’s Health. 15, 1–6 (2015).

Nooh, A. M., Abdul-Hady, A. & El-Attar, N. Nature and prevalence of menstrual disorders among teenage female students at Zagazig University, Zagazig, Egypt. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 29, 137–142 (2016).

Szmidt, M. K., Granda, D., Sicinska, E. & Kaluza, J. Primary dysmenorrhea in relation to oxidative stress and antioxidant status: A systematic review of case-control studies. Antioxidants 9, 994 (2020).

Yilmaz, F. A. & Dilek, A. Effect of dysmenorrhea on quality of life in university students: A case-control study. Cukurova Med. J. 45, 648–655 (2020).

Trevis, K. J., McLachlan, N. M. & Wilson, S. J. A systematic review and meta-analysis of psychological functioning in chronic tinnitus. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 60, 62–86 (2018).

Chang, P. J. & Hsieh, C. H. E. N. P. C. Chiu, L. T. Risk factors on the menstrual cycle of healthy Taiwanese college nursing students. Aust. N. Z. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 49, 689–694 (2009).

Mittiku, Y. M., Mekonen, H., Wogie, G., Tizazu, M. A. & Wake, G. E. Menstrual irregularity and its associated factors among college students in Ethiopia, 2021. Front. Global Women’s Health. 3, 917643 (2022).

Wu, L., Zhang, J., Tang, J. & Fang, H. The relation between body mass index and primary dysmenorrhea: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 101, 1364–1373 (2022).

Seif, M. W., Diamond, K. & Nickkho-Amiry, M. Obesity and menstrual disorders. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 29, 516–527 (2015).

Marchiori, L. L. et al. Do body Mass Index levels correlate with tinnitus among teachers? Int. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 26, 63–68 (2022).

Cobb, K. L. et al. Disordered eating, menstrual irregularity, and bone mineral density in female runners. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 35, 711–719 (2003).

Wang, L. et al. Prevalence and risk factors of primary dysmenorrhea in students: A meta-analysis. Value Health. 25, 1678–1684 (2022).

Tang, D. et al. Dietary fibre intake and the 10-year incidence of tinnitus in older adults. Nutrients 13, 4126 (2021).

Carroquino-Garcia, P. et al. Therapeutic exercise in the treatment of primary dysmenorrhea: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Phys. Ther. 99, 1371–1380 (2019).

Eliakim, A. & Beyth, Y. Exercise training, menstrual irregularities and bone development in children and adolescents. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 16, 201–206 (2003).

Özbey-Yücel, Ü. et al. The effects of diet and physical activity induced weight loss on the severity of tinnitus and quality of life: A randomized controlled trial. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN. 44, 159–165 (2021).

Jenabi, E., Khazaei, S. & Veisani, Y. The relationship between smoking and dysmenorrhea: A meta-analysis. Women Health. 59, 524–533 (2019).

Bae, J., Park, S. & Kwon, J. W. Factors associated with menstrual cycle irregularity and menopause. BMC Women’s Health. 18, 1–11 (2018).

Veile, A., Zimmermann, H., Lorenz, E. & Becher, H. Is smoking a risk factor for tinnitus? A systematic review, meta-analysis and estimation of the population attributable risk in Germany. BMJ Open 8 (2018).

Nam, G. E., Han, K. & Lee, G. Association between sleep duration and menstrual cycle irregularity in Korean female adolescents. Sleep Med. 35, 62–66 (2017).

Sun, H. et al. Risk factors of decompensated tinnitus and the interaction effect of anxiety and poor sleep on decompensated tinnitus: A multicenter study. Acta Otolaryngol. 141, 1049–1054 (2021).

Park, M., Kang, S. H., Nari, F., Park, E. C. & Jang, S. I. Association between tinnitus and depressive symptoms in the South Korean population. PLoS ONE. 16, e0261257 (2021).

Jacobson, M. H. et al. Thyroid hormones and menstrual cycle function in a longitudinal cohort of premenopausal women. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 32, 225–234 (2018).

Birke, L., Baston-Büst, D. M., Kruessel, J. S., Fehm, T. N. & Bielfeld, A. P. Can TSH level and premenstrual spotting constitute a non-invasive marker for the diagnosis of endometriosis? BMC Women’s Health. 21, 1–9 (2021).

Hsu, A. et al. Hypothyroidism and related comorbidities on the risks of developing tinnitus. Sci. Rep. 12, 3401 (2022).

Singh, V. et al. Association between serum 25-hydroxy vitamin D level and menstrual cycle length and regularity: A cross-sectional observational study. Int. J. Reprod. Biomed. 19, 979 (2021).

Amzajerdi, A., Keshavarz, M., Ghorbali, E., Pezaro, S. & Sarvi, F. The effect of vitamin D on the severity of dysmenorrhea and menstrual blood loss: A randomized clinical trial. BMC Women’s Health. 23, 1–7 (2023).

Abdul-Razzak, K. K., Obeidat, B. A., Al-Farras, M. I. & Dauod, A. S. Vitamin D and PTH status among adolescent and young females with severe dysmenorrhea. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 27, 78–82 (2014).

Haghighian, H. K. Is there a relationship between serum vitamin D with dysmenorrhea pain in young women? J. Gynecol. Obstet. Hum. Reprod. 48, 711–714 (2019).

Nowaczewska, M. et al. The role of vitamin D in subjective tinnitus—A case-control study. PLoS ONE. 16, e0255482 (2021).

Bianchin, L. et al. Menstrual cycle and headache in teenagers. Indian J. Pediatr. 86, 25–33 (2019).

Bessa, D. R. et al. Association between headache and tinnitus among medical students. Arq. Neuropsiquiatr. 79, 982–988 (2021).

Von Elm, E. et al. The strengthening the reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int. J. Surg. 12, 1495–1499 (2014).

Pearce, M. et al. Association between physical activity and risk of depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 79 (6), 550–559 (2022).

Kim, H. K., Kim, H. S. & Kim, S. J. Association of anxiety, depression, and somatization with menstrual problems among North Korean women defectors in South Korea. Psychiatry Invest. 14 (6), 727 (2017).

Niazi, A. R. et al. Fertility status and depression: A case-control study among women in Herat, Afghanistan. Health Sci. Rep. 7 (9), e70063 (2024).

Ahlawat, P. et al. Prevalence of depression and its association with sociodemographic factors in postmenopausal women in an urban resettlement colony of Delhi. J. Mid-life Health. 10 (1), 33–36 (2019).

Deierlein, A. L. et al. Mental health outcomes across the reproductive life course among women with disabilities: A systematic review. Arch. Women Ment. Health :1–18. (2024).

Zaks, N. et al. Association between mental health and reproductive system disorders in women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open. 6 (4), e238685–e238685 (2023).

Li, Y. et al. Association between depression and dysmenorrhea among adolescent girls: Multiple mediating effects of binge eating and sleep quality. BMC Women’s Health. 23 (1), 140 (2023).

Park, M. et al. Association between tinnitus and depressive symptoms in the South Korean population. PLoS ONE. 16 (12), e0261257 (2021).

Molnár, A. et al. Correlation between tinnitus handicap and depression and anxiety scores. Ear Nose Throat J. 01455613221139211. (2022).

Lin, X. et al. Association between depression and tinnitus in US adults: A nationally representative sample. Laryngosc. Invest. Otolaryngol. 8 (5), 1365–1375 (2023).

Appleyard, C. B., Flores, I. & Torres-Reverón, A. The link between stress and endometriosis: From animal models to the clinical scenario. Reprod. Sci. 27, 1675–1686 (2020).

Qin, H., Lin, Z., Vásquez, E. & Xu, L. The association between chronic psychological stress and uterine fibroids risk: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Stress Health. 35, 585–594 (2019).

Song, S. Y. et al. Long-term efficacy and feasibility of levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device use in patients with adenomyosis. Medicine 99, e20421 (2020).

Al-Katib, S. R., Hasson, Y. L. & Shareef, R. H. Association between iron deficiency and hearing loss. Biochem. Cell. Archiv. 19 (2019).

Grampurohit, A., Sandeep, S., Ashok, P. & Shilpa, C. Thanzeemunissa. Study of association of sensory neural hearing loss with iron deficiency anaemia. Indian J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 74, 3800–3805 (2022).

Sunwoo, W. et al. Characteristics of tinnitus found in anemia patients and analysis of population-based survey. Auris Nasus Larynx. 45, 1152–1158 (2018).

Althubaiti, A. Information bias in health research: Definition, pitfalls, and adjustment methods. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 9, 211 (2016).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the study participants.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MZ: Conception, design, interpretation, writing the manuscript, supervising the study and the submission process. editing and reviewing the final manuscript. BA: Data analysis, interpretation, writing the manuscript, editing and reviewing the final manuscript. MZ and BA contributed equally to this study and are considered co-first authors. AN: Conception, design, data collection, interpretation, preparing the initial draft of the manuscript and further editing. MN: Recruitment, piloting and data collection. AB: Study design, reviewing the manuscript. All the authors approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: In the original version of this Article the authors Amani Nanah, Manar Nanah and Asma S. Basha were incorrectly affiliated. Full information regarding the correction can be found in the correction published with this article.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zuriekat, M., Al-Rawashdeh, B., Nanah, A. et al. The link between tinnitus and menstrual cycle disorders in premenopausal women. Sci Rep 15, 2821 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87408-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87408-7