Abstract

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the epidemiological characteristics of depression among adults in the U.S. remains unclear. This study aims to analyze trends in depression prevalence over time and quantify the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on its prevalence. Using data from 2007 to 2023 provided by the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES), this study examined 36,472 participants. Results revealed an increasing trend in depression prevalence among U.S. adults from 2007 to 2023. Notably, the overall weighted prevalence of depression following the COVID-19 pandemic (12.4%, 95% CI: 10.6-14.1%) was significantly higher than in all years prior to the pandemic. Subgroups such as females, Mexican Americans, and young adults experienced particularly pronounced increases. By analyzing data from two survey cycles close to the onset of the COVID-19 outbreak, the study identified a significant impact of the pandemic on depression prevalence, with an adjusted odds ratio of 1.58 (95% CI: 1.28–1.94). Individuals with lower socioeconomic status and those without pre-existing conditions exhibited greater increases in depression prevalence, whereas the emotional health of individuals who smoke appeared unaffected by the pandemic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Depression is a serious mental health disorders that affects US adults, serving as one of the most disabling mental health disorders and contributing an enormous burden to the health and well-being of individuals, and this burden is high across the entire lifespan1,2.

Since the outbreak of COVID-19 pandemic in 2019, it has impacted multiple aspects of daily life3. In addition to the burden caused by the infection of COVID-19 itself, it also leads to several complications and changes in behavior and lifestyle habits, such as increased assumption of alcohol and tobacco and reduced time for physical exercise, which can be significant risk factors for depression symptoms4,5,6. Furthermore, in governments’ attempts to control the spread of COVID-19, social restrictions, school and business closures and decreases in social, economy, and physical activity are all potentially affect public mental health7.

An increase in depressive symptoms due to the COVID-19 pandemic has been observed in many populations, particularly among females, including pregnant women and new mothers, healthcare givers and young students8,9,10,11,12. However, to our knowledge, little large population-based studies have assessed the prevalence of depression in adults considering the long-term impact of the COVID-19 outbreak in the United states, for example, Renee D Goodwin et al. conducted a research and detected an increasing trend of depression prevalence in U.S from 2015 to 2019 and estimates for 2020 were not added in the trend analysis since the COVID-19 pandemic made the data collection method different and data collected in 2020 incomparable with previous estimates13. And little is known about the persistence of changes in the prevalence of depression within the overall population or among subgroups differentiated by gender, age group or race in the United States. It also remains unclear whether the dramatic changes in lifestyle, health status and social activities resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic have led to individual-specific risk of depression. The demand for up-to data information on the prevalence, which incorporates the mental health impact of COVID-19 pandemic, is more crucial than ever.

The purpose of this study was to assess the prevalence of depression among individuals aged 20 years and older during the pandemic of COVID-19. Data were drawn from the National Health and Nutritional Examination Surveys (NHANES), which employs complex, multistage, probabilistic sampling method to collect representative health-related data on the US population14, and data collected from three period: five two-year cycles from 2007 to 2016, the 2017-March 2020 cycle and the August 2021-August 2023 cycle were analyzed in this study. Changes in the trend of depression among U.S adults from 2017 to 2023 were reported by age group, gender and race to see whether the COVID-19 pandemic significantly increased the prevalence of depression, and the influence were also quantified based on the data collected in the last two cycles which was close to the onset of COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

Study design and population

Utilizing data from the NHANES collected in three period: five cycles of every two years from 2007 to 2016, the 2017-March 2020 cycle (combined data collected from 2019 to March 2020, which suspended field operations in March 2020 due to COVID-19 pandemic, with data from the NHANES 2017–2018 cycle to form a nationally representative sample), and the August 2021 to August 2023 cycle, this study analyzed trends in the prevalence of depression from 2017 to 2023 to detect the impact caused by COVID-19 pandemic. And to further quantify this individual-specific effect, considering the comparability of sample sizes, data collected in 2017-March 2020 was defined as “pre COVID-19” and data collected from August 2021 to August 2023 was defined as “during COVID-19” since the World health Organization declared an end to the global public health emergency for COVID-19 on May 11, 2023.

Among the 78 081 participants surveyed in NHANES in above-mentioned three periods, 37 752 participants did not compete the depression screening or had missing data. A further 2 394 participants were excluded due to age restrictions (≥ 20 years old) or pregnancy status, and 1 463 were excluded due to missing demographics data and other covariates. Ultimately, 3 6472 participants were included in this study, with 7 495 from the “pre COVID-19” period and 4 994 from the “during COVID-19” period. (Fig. 1).

Assessment of depression

Depression was assessed using the nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), which consists of nine questions, each rated on a scale from 0 to 315,16. The PHQ-9 has been validated as an effective screening tool for current depressive episodes, even during the period of COVID-19 epidemic15,16,17. The total PHQ-9 score ranges from 0 to 27, with higher scores indicating more severe depressive symptoms. Participants with a total score greater than 9 were considered to have depression15,16.

Covariates

Covariates were selected based on previous research6,12,18,19,20,21. Demographic covariates include gender (male and female), race/ethnicity (Mexican American, Other Hispanic, Non-Hispanic white, Non-Hispanic black, other race), age groups (≤ 39, 40 ~ 59, ≥ 60), education (less than high school, high school or equivalent, above high school), poverty-income ratio (PIR: <1.30, 1.30 ~ 3.49, > 3.49), body mass index (BMI: <25.0, 25.0 ~ 29.9, > 29.9), marital status (married/living with a partner, widowed/divorced/separated, never married), hypertension, diabetes and smoking status were categorized as binary variables (yes or no). Alcohol consumption was classified into three levels (mild, moderate and heavy) based on gender differences. The sudden outbreak of COVID-19 made some interesting covariates unavailable to be collected, so another reason why we utilized above-mentioned covariates was that all these covariates were collected and measured in a consistent frame in these three cycles of data collection.

Statistical analysis

All analysis were conducted using sample weights to account for the complex sampling design of NHANES, and data were weighted using the survey weight WTMEC2YR under the analytic guidance provide by NHANES and the survey weights was adjusted to reflect the longer period and larger population represented in utilized data14. For example, we combined the data collected in all these three cycles, which would result in a data file representing a 15.2-year period, the survey weights for the trend analysis of the period of 2007–2023 was adjusted as follows: 2007–2016 and August 2021-August 2023 survey weights was multiplied by 2/15.2 and likewise, the 2017-March 2020 survey weights should be multiplied by 3.2/15.2. And similar weight adjustment was conducted in the quantification analysis of the risk induced by COVID-19 pandemic based on the data collected in 2017-March 2021 cycle and Aug 2021-Aug 2023 cycle. Detailed information about data collection and population definition can be found elsewhere14.

Data missing posed a great challenge to data analysis, in addition to the target variable (depression), other covariates also had substantial missing data, so we could only compare basic characteristics (gender, race and age group) of participants with missing depression data and those with complete depression data, the non-missing group appeared to be more representative of the target population distribution. For example, in the non-missing group, the proportions of age groups (< 39: 35.9%, 40–59: 36.7%, ≥ 60: 27.4%) and racial distribution (White: 66.7%, Black: 10.9%, Mexican: 8.1%) were more balanced and closer to the general NHANES population. In contrast, the missing group showed clear biases, such as a predominance of younger individuals (< 39: 83.6%) and a lower proportion of non-Hispanic White participants (52.9%) (Appendix Table 1). And missing data in nearly half of the participants, affecting both the outcome variable and covariates, renders multiple imputation unsuitable due to the risk of introducing new bias. Therefore, this study was conducted based on participants with complete depression data.

Non-adjusted prevalence estimates for depression were calculated for different age groups, genders and racial/ethnic groups. Chi-square test and fisher’s exact test were used to compare the characteristics between participants with and without depression. Subsequently, logistic regression models were employed to tested the effect of COVID-19 pandemic in the depression prevalence and we quantified the effect by estimating crude odds ratios (CORs) as well as adjusted odds ratios (AORs), adjusted for the eleven covariates described above. Statistical analyses were performed using RStudio (version 2022.07.0 for windows) and R (version 4.4.1), with a two-tailed P value of less than 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Results

Among the 36 472 participants surveyed in above-mentioned three period, 434 million U.S. residents were represented.

Overall prevalence of depression

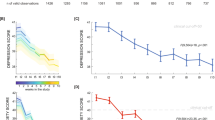

An increasing trend of the prevalence of depression of the U.S adults was observed from 2007 to 2023 and the overall weighted prevalence of depression after the COVID-19 pandemic (12.4%, 95% CI: 10.6 – 14.1%) were significantly higher than the prevalence of all previous year before COVID-19. (Fig. 2, Appendix Table 2).

The weighted prevalence of depression among U.S adults from 2007 to 2023 (A overall trend; B trend by genders; C trend by age groups; D trend by races). Note: The 2017–2020 data was a nationally representative data generated by combining data collected from 2019 to March 2020, which suspended field operations in March 2020 due to COVID-19 pandemic, with data from the NHANES 2017–2018 cycle.

Gender disparities

An increasing trend of the prevalence of depression was observed in both genders and it was consistently lower among males compared to females in all the observed years. Specifically, the depression prevalence for males after the outbreak of COVID-19 was 10.1% (95% CI: 8.1 – 12.1), while for females, it was 14.7% (95% CI: 12.5 – 16.8). (Figures 2 and 3, Appendix Table 2, Appendix Table 3).

The weighted prevalence of depression among U.S adults by genders, age groups and races from 2007 to 2023. Note: The 2017–2020 data was a nationally representative data generated by combining data collected from 2019 to March 2020, which suspended field operations in March 2020 due to COVID-19 pandemic, with data from the NHANES 2017–2018 cycle.

Age-related trends

The prevalence of depression varied across age groups, with younger individuals experiencing the most significant changes following the pandemic. Among individuals under 39 years old, the prevalence of depression increased from 7.9% (95% CI: 7.3 – 8.6) in 2007–2008 to 16.6% (95% CI: 14.7 – 18.4) during the period from August 2021 to August 2023. A slight increase was also observed in individuals aged 40–59 years and those aged 60 and above. (Figures 2 and 3, Appendix Table 2, Appendix Table 3).

Racial variations

The greatest increase of the trend of the prevalence was observed in Mexican Americans, with the rate rising from 8.2% (95% CI: 7.4 – 9.0) to 14.6% (95% CI: 12.9 – 16.3) over the observed years. A similar trend was seen across other racial groups, with the order of the increase being: other racial groups, non-Hispanic whites, non-Hispanic blacks, and other Hispanics. The smallest change was noted among other Hispanics, with the prevalence rising from 13.1% (95% CI: 11.7 – 14.5) to 13.6% (95% CI: 12.2 – 15.0), though it remained at a relatively high level throughout most of the years. (Figures 2 and 3, Appendix Table 2, Appendix Table 3).

Baseline characteristics of study population

To ensure the comparability of the data volume as well as the timeliness and representativeness of the data, we combined data from 2017-March 2020 cycle and August 2021 to August 2023 cycle to further analyze the characteristics of individuals with and without depression. Firstly, the characteristics of participants from these two cycles were compared, and significant differences were observed in lifestyle indicators: smoke and alcohol, people smoke and drink less after the outbreak of COVID-19 pandemic (Appendix Table 4). Secondly, the characteristics of individuals with and without depression was also compared and we found statistically significant differences in most of the covariates except races and alcohol use. (Table 1).

Individual-specific influence of the COVID-19 pandemic

The significant impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on the prevalence of depression among U.S. adults was quantified with an statistically significant AOR of 1.58 (95% CI: 1.28 – 1.94) and the mental health burden was disproportionately higher among specific demographic groups, including males (AOR = 1.81, 95% CI: 1.37 – 2.40), younger adults under 39 years (AOR = 2.28, 95% CI: 1.59 – 3.26), Mexican Americans (AOR = 2.66, 95% CI: 1.31 – 5.38), and those with lower educational attainment (less than high school: AOR = 1.71, 95% CI: 1.35 – 2.17). Socioeconomic disparities further amplified this burden, with individuals in poverty (1.30 ≤ PIR ≤ 3.49: AOR = 1.64, 95% CI: 1.22 – 2.22) and never-married adults (AOR = 2.00, 95% CI: 1.31 – 3.03) showing significantly increased odds of depression. Additionally, health-related factors such as higher BMI (AOR = 1.55, 95% CI: 1.15 – 2.08) and moderate alcohol use (AOR = 2.65%, 95% CI: 1.37 – 5.12) were associated with greater susceptibility to depression during the pandemic. Besides, individuals who were not suffering from hypertension (AOR = 2.05, 95% CI: 1.61 – 2.60) and diabetes (AOR = 1.71, 95% CI: 1.35 – 2.15) and individuals who did not smoke (AOR = 2.06, 95% CI: 1.60 – 2.65) were more easily affected by the pandemic. (Table 2).

Discussion

This study examined the change of the trend of depression prevalence among the U.S adults based on data provided by NHANES from 2007 to 2023 and using data from 2017-March 2020 and August 2021-August 2023, this study also evaluated the individual-specific influence of the COVID-19 pandemic. And three significant findings emerged: (a) The overall weighted prevalence of depression during the period of COVID-19 pandemic was 12.4% (95% CI: 10.6 – 14.1%), greatly higher than previous years; (b) Notable increases in depression rates were observed in specific subgroups, particularly among younger adults, females, and Mexican Americans; (c) Individuals with lower socioeconomic status and those without pre-existing conditions were greatly influenced by the pandemic and exhibited greater increases in depression prevalence.

Considering that the sudden outbreak of COVID-19 pandemic disrupted many health-related data collection programs and thus relevant evidence is lacked, and based on nationwide representative and well-designed NHANES data, this study provided a strong support for the conclusion drawn by previous study, where only crude prevalence of depression during the COVID-19 pandemic was estimated based on previous data.

The substantial rise of the depression prevalence may suggest that the pandemic had a profound impact on population mental health, which is consistent with previous research findings1,22,23. Previous research proved depression prevalence would continue to increase due to the changing social, economic, and cultural conditions, as well as greater awareness and improved diagnosis of mental health issues, but the pandemic likely amplified certain stressors that contributed to the rise in depression prevalence13. The stressors associated with the pandemic, such as social isolation, economic uncertainty, health concerns, as well as fear for infection and doubts regarding vaccines safety, likely contributed to this increase. Besides, strategies implemented to control the spread of COVID-19 also made it difficult to acquire timely access to medication and in-person care, as many outpatients and inpatients are going directly to COVID-19 patients at the beginning stage of COVID-19 pandemic24,25.

Notably, the study revealed significant increases in depression rates within specific subgroups, particularly among younger adults, females, and Mexican American individuals. The rise in depression among younger adults may be attributed to reduced social connections due to the isolation and social distancing and school closure, and pressure related to establishing independence and starting careers26. Similarly, the higher prevalence among females may reflect the compounded stressors they experienced, such as caregiving responsibilities, more severe COVID-19 outcomes, heightened vulnerability to mental health issues, and hormonal differences27,28. The increase in depression among Mexican American adults likely reflect the unique challenges faced by this group, including socioeconomic disparities, limited access to mental health resources and greater exposure to pandemic-related stressors, such as living in crowded households or serving in essential but high-risk professions. Additionally, residents who are females, younger adults and Mexican American are more likely to lose their job29, and the unemployment rates in the U.S. exceeded to 14% following the outbreak of COVID-1930,31.

Individuals with lower educational attainment and income levels experienced significant increases in depression prevalence during the pandemic18. Many families experienced sharp declines in income due to unemployment and isolation, worsening mental health outcomes32, since family income is closely tied to access to healthcare or vaccines23, and previous research indicates that economy crises are often associated with increasing depression prevalence across multiple years and countries21,33,34. Lower socioeconomic status likely amplified the mental health impact of the pandemic due to greater financial instability, limited access to healthcare, and increased exposure to COVID-19 risks in frontline jobs29. Marital status also significantly influenced the increase in depression prevalence, and strict public health measures, including social distancing, increased acute stress due to loneliness and diminished feeling of social connection, especially among those living alone, which was also proved in this study since individuals who were widowed/divorced/separated and never married were more likely to be depressed than individuals who were married or living with a partner, as loneliness and small social network are closely associated with depression symptoms18.

Individuals without pre-existing conditions like hypertension and diabetes showed larger increases in depression prevalence, suggesting that those previously perceived as “healthy” may have been more affected by the pandemic’s sudden and unexpected health risks and lifestyle changes. Additionally, smoking and alcohol consumption behaviors influenced depression rates. Non-smokers experienced a greater increase in depression prevalence compared to smokers. This may reflect differing coping mechanisms, where individuals who smoke may have relied on their habits to manage stress4,5,6. However, further research is needed to elucidate this relationship.

The findings of this study underscore the urgent need for public health initiatives aimed at addressing the rising prevalence of depression, especially among vulnerable groups such as women and younger adults. To mitigate the long-term effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, policies should prioritize tackling unemployment issues faced by these populations, as well as addressing the inequitable allocation of medical resources. Beyond the uncertainties and fears associated with COVID-19, the increase in depression during the pandemic was also significantly shaped by the preventive measures implemented to limit the spread of virus, which is critical for consideration in future policy research, ensuring that mental health support is a core component of both current and future public health strategies.

This study has several limitations. First, using cross-sectional data from pre- and during-COVID time points to explore the impact of COVID-19 on depression is appropriate for exploring trends and establishing preliminary associations. However, since this design does not allow for causal inference, findings should be interpreted cautiously. Second, the analysis relied on self-reported measures of depression, which may introduce recall bias and reporting bias, potentially underestimating or overestimating prevalence rates. Third, as with other studies using the NHANES database, missing data is a common issue that can limit the robustness of subgroup analyses and lead to potential biases if the missingness is not random. Although statistical techniques such as weighting and adjustments were employed to address these gaps, residual confounding may remain. Future research should focus on longitudinal data and integrate additional factors, such as the role of social support and access to digital mental health services, to better understand the pandemic’s long-term mental health effects.

Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic significantly impacted the prevalence of depression, particularly among females, younger adults and specific socioeconomic groups and the increase indicates that the COVID-19 pandemic may have altered the landscape of mental health risk factors since great shift has been observed before and after this pandemic. These findings underscore the urgent need for public policies, especially targeting the most vulnerable populations severely affected by the pandemic, and mental health services must adapt to this shift and provide targeted support to mitigate the long-term psychological impacts of COVID-19 pandemic.

Data availability

The publicly data in this study are available for NHANES database in the centers for disease control and prevention in the United States and can be found here: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm.

References

COVID-19 Mental Disorders Collaborators. Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 398 (10312), 1700–1712 (2021).

Rehm, J. & Shield, K. D. Global burden of Disease and the impact of Mental and Addictive disorders. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 21 (2), 10 (2019).

Wu, F. et al. A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature 579 (7798), 265–269 (2020).

Sidor, A. & Rzymski, P. Dietary choices and habits during COVID-19 Lockdown: experience from Poland. Nutrients 12 (6), 1657 (2020).

Piva, T. et al. Exercise program for the management of anxiety and depression in adults and elderly subjects: is it applicable to patients with post-covid-19 condition? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 325, 273–281 (2023).

Yuan, K. et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis on prevalence of and risk factors associated with depression, anxiety and insomnia in infectious diseases, including COVID-19: a call to action. Mol. Psychiatry. 27 (8), 3214–3222 (2022).

Lok, V. et al. Changes in anxiety and depression during the COVID-19 pandemic in the European population: a meta-analysis of changes and associations with restriction policies. Eur. Psychiatry 66(1), e87 (2023).

Patabendige, M., Gamage, M. M., Weerasinghe, M. & Jayawardane, A. Psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic among pregnant women in Sri Lanka. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 151 (1), 150–153 (2020).

Rohde, J. F. et al. Associations of COVID-19 stressors and Postpartum Depression and anxiety symptoms in New Mothers. Matern. Child Health J. 27 (10), 1846–1854 (2023).

Zhu, J. et al. Prevalence and influencing factors of anxiety and depression symptoms in the First-Line Medical Staff fighting against COVID-19 in Gansu. Front. Psychiatry. 12, 653709 (2021).

Scott, A. M. & Stafford, L. Engaged women’s relationships, weddings, and Mental Health during Covid-19. J. Fam. Issues. 43 (12), 3346–3372 (2022).

Khuram, H., Maddox, P. A., Hirani, R. & Issani, A. The COVID-19 pandemic and depression among medical students: barriers and solutions. Prev. Med. 171, 107365 (2023).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). About the national health and nutrition exammination survey. Preprint at (2023). https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/about_nhanes.htm

Goodwin, R. D. et al. Trends in U.S. Depression Prevalence from 2015 to 2020: the Widening Treatment Gap. Am. J. Prev. Med. 63 (5), 726–733 (2022).

Beard, C., Hsu, K. J., Rifkin, L. S., Busch, A. B. & Bjoergvinsson, T. Validation of the PHQ-9 in a psychiatric sample. J. Affect. Disord. 193, 267–273 (2016).

Sun, Y., Kong, Z., Song, Y., Liu, J. & Wang, X. The validity and reliability of the PHQ-9 on screening of depression in neurology: a cross sectional study. Bmc Psychiatry. 22 (1), 98 (2022).

Shevlin, M. et al. Measurement invariance of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) and generalized anxiety disorder scale (GAD-7) across four European countries during the COVID-19 pandemic. Bmc Psychiatry. 22 (1), 154 (2022).

Schaakxs, R. et al. Risk factors for Depression: Differential Across Age? Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 25 (9), 966–977 (2017).

Nie, X. D. et al. Anxiety and depression and its correlates in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan. Int. J. Psychiatry Clin. Pract. 25 (2), 109–114 (2021).

Smith, L. et al. Association between COVID-19 and subsequent depression diagnoses-A retrospective cohort study. J. Epidemiol. Popul. Health. 72 (4), 202532 (2024).

Madianos, M., Economou, M., Alexiou, T. & Stefanis, C. Depression and economic hardship across Greece in 2008 and 2009: two cross-sectional surveys nationwide. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 46 (10), 943–952 (2021).

Xiang, A. H. et al. Depression and anxiety among US children and young adults. JAMA Netw. Open. 7(10), e2436906 (2024).

Nguyen, K. H. et al. Prior COVID-19 diagnosis, severe outcomes, and long COVID among U.S. adults, 2022. Vaccines (Basel). 12 (6), 669 (2024).

Campion, J., Javed, A., Sartorius, N. & Marmot, M. Addressing the public mental health challenge of COVID-19. Lancet Psychiatry. 7 (8), 657–659 (2020).

Moreno, C. et al. How mental health care should change as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry. 7 (9), 813–824 (2020).

Arnett, J. J. Emerging adulthood. A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am. Psychol. 55 (5), 469–480 (2020).

Albert, P. R. Why is depression more prevalent in women? J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 40 (4), 219–221 (2015).

Wenham, C. et al. Women are most affected by pandemics - lessons from past outbreaks. Nature 583 (7815), 194–198 (2020).

Montenovo, L. et al. Determinants of disparities in early COVID-19 job losses. Demography 59 (3), 827–855 (2022).

Bartik, A. W., Bertrand, M., Lin, F., Rothstein, J. & Unrath, M. Measuring the Labor Market at the Onset of the COVID-19 Crisis. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity. 239–268 (2020).

Ringlein, G. V., Ettman, C. K. & Stuart, E. A. Income or job loss and psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw. Open. 7(7), e2424601 (2024).

McGinty, E. E., Presskreischer, R., Han, H. & Barry, C. L. Psychological distress and loneliness reported by US adults in 2018 and April 2020. JAMA 324 (1), 93–94 (2020).

Frasquilho, D. et al. Mental health outcomes in times of economic recession: a systematic literature review. BMC Public. Health. 16, 115 (2016).

Economou, M., Madianos, M., Peppou, L. E., Patelakis, A. & Stefanis, C. N. Major depression in the era of economic crisis: a replication of a cross-sectional study across Greece. J. Affect. Disord. 145 (3), 308–314 (2013).

Acknowledgements

We express our sincere gratitude to the participants and staff of the NHANES for their valuable contributions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yun Jiang: Writing – Original draft, Methodology, Data curation, Conceptualization. Wusheng Deng: Validation, Supervision, Conceptualization. Mei Zhao: Supervision, Conceptualization.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics statement

All analyses were based on secondary dataset and no ethical approval and patient are required.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, Y., Deng, W. & Zhao, M. Influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on the prevalence of depression in U.S. adults: evidence from NHANES. Sci Rep 15, 3107 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87593-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87593-5

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Neutrophil-to-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio (NHR) mediates the relationship between abdominal fat index and depression in a cross-sectional study

BMC Psychiatry (2025)

-

A rank ordering and analysis of nine resilience competencies demonstrates the special importance of thought management in maintaining resilience

Scientific Reports (2025)