Abstract

Due to the aging of the global population and lifestyle changes, cardiovascular disease has become the leading cause of death worldwide, causing serious public health problems and economic pressures. Early and accurate prediction of cardiovascular disease is crucial to reducing morbidity and mortality, but traditional prediction methods often lack robustness. This study focuses on integrating swarm intelligence feature selection algorithms (including whale optimization algorithm, cuckoo search algorithm, flower pollination algorithm, Harris hawk optimization algorithm, particle swarm optimization algorithm, and genetic algorithm) with machine learning technology to improve the early diagnosis of cardiovascular disease. This study systematically evaluated the performance of each feature selection algorithm under different population sizes, specifically by comparing their average running time and objective function values to identify the optimal feature subset. Subsequently, the selected feature subsets were integrated into ten classification models, and a comprehensive weighted evaluation was performed based on the accuracy, precision, recall, F1 score, and AUC value of the model to determine the optimal model configuration. The results showed that random forest, extreme gradient boosting, adaptive boosting and k-nearest neighbor models performed best on the combined dataset (weighted score of 1), where the feature set consisted of 9 key features selected by the cuckoo search algorithm when the population size was 25; while on the Framingham dataset, the k-nearest neighbor model performed best (weighted score of 0.92), and its feature set was derived from 10 features selected by the whale optimization algorithm when the population size was 50. The results of this study show that swarm intelligence algorithms can effectively screen key and informative feature sets, significantly improve model classification accuracy, and provide strong support for the early diagnosis of cardiovascular diseases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As global aging accelerates and lifestyles change rapidly, cardiovascular disease (CVD) has emerged as the leading cause of death worldwide. This situation presents significant public health challenges and contributes to a substantial disease burden that must be addressed1. CVD includes a range of conditions that impact the heart and blood vessels, such as coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular disease, and rheumatic heart disease, each with its own unique pathology. Importantly, over 80% of deaths due to CVD are attributed to heart attacks and strokes2. In the past 30 years, the prevalence and mortality rates of CVD have shown an upward trend, with the number of individuals currently affected by CVD rising from 270 million to 540 million and the death toll increasing from 12.1 million to 18.6 million3. Globally, it is estimated that by 2030, the total healthcare costs of cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) will rise to $1.044 trillion4. CVD has become a significant public health issue affecting the health and lifespan of populations worldwide5.

Early detection of CVD is essential to lower both morbidity and mortality rates6. The arrival of the big data era has opened new opportunities for predicting CVD using artificial intelligence, particularly machine learning (ML) and deep learning7,8,9. These techniques can detect early warning signs of declining heart health by tracking critical physiological parameters, including blood pressure, heart rate, etc. However, despite the great potential of ML in CVD prediction, there are still many challenges in achieving accurate and stable predictions, as the explosive growth of feature numbers in large datasets often becomes a key factor limiting model performance10. Too many features can cause overfitting, which limits the model’s ability to generalize to new data. They also increase computational complexity and training time, which negatively impacts the model’s overall efficiency11. Therefore, to enhance the classifier’s learning efficiency, it is crucial to carefully select a feature set that is both compact and rich in essential information12,13. To achieve this objective, it is crucial to include a preprocessing step for the data, focusing on feature selection and removing those that are not representative. As a key step in data preprocessing, feature selection is irreplaceable in optimizing the modeling process and improving model performance14. This approach helps minimize noise and redundancy, prevents overfitting15, enhances the model’s generalization ability, speeds up the training process, and ultimately improves efficiency16.

Feature selection techniques can be categorized into filter-based, wrapper-based, embedded, hybrid, and swarm intelligence methods, which have emerged in recent years based on their distinct working principles17,18. Filter methods are known to be efficient and independent, focusing on the intrinsic properties of features rather than inter-feature dependencies19. In contrast, wrapper methods make up for the shortcomings of filters by using classifiers to evaluate the performance of feature subsets and considering the interdependencies between features, but they are computationally expensive. The embedded feature selection method combines the classifier to directly search for the optimal feature set and track feature dependencies with lower complexity20,21. It offers higher efficiency than the wrapper method and lowers the risk of overfitting, though the computational cost remains significant22. Although hybrid methods improve model accuracy by integrating multiple feature selection technologies, the complexity and computational cost cannot be ignored. At the same time, algorithm fusion and collaboration need to be carefully processed during use, making hybrid methods very complex to implement. Because of the limitations of the above-mentioned feature selection method, the swarm intelligence optimization method has emerged in feature selection and has become a robust method in many fields. This approach relies on the collective behavior of self-organizing, decentralized systems. It draws on the random behavior of biological groups and the emerging orderly patterns to form an effective problem-solving strategy by simulating the natural biological behavior mechanism, efficiently searching the feature space, identifying the optimal feature subset, and improving the effect and efficiency of feature selection. Feature selection is an NP-hard problem, with the main challenge being the exponentially expanding search space for the optimal subset as the feature count grows in high-dimensional datasets. For a dataset with N features, the total number of potential feature subsets is 2N-1, demanding that the algorithm have robust global optimization capabilities and strong noise resistance to tackle this challenge23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30. Therefore, when the exact algorithm cannot obtain a satisfactory solution within a reasonable time31, swarm intelligence algorithms become an important tool for identifying effective feature subsets. The “No Free Lunch”32 theorem highlights that no single algorithm can universally and effectively solve all complex real-world problems. This understanding has greatly promoted the development and growth of swarm intelligence methods. Past research works have widely adopted a variety of swarm intelligence algorithms to meet various challenges from different industries and fields. These algorithms include but are not limited to genetic algorithm (GA)33, whale optimization algorithm (WOA)18,34, particle swarm optimization (PSO)35,36, ant colony optimization (ACO)37, flower pollination algorithm (FPA)38, firefly algorithm (FA)39, cuckoo search algorithm (CSA)40, simulated annealing (SA)41, transient search optimization (TSO)42, harris hawk optimization (HHO)43, bat algorithm (BA)44 and gray wolf optimization (GWO)45. These algorithms provide high-quality solutions to various complex situations within a reasonable time frame.

Previous research on CVD prediction has primarily focused on optimizing algorithms through various ML techniques, often aiming to enhance these algorithms using different feature selection methods or comparing the impact of different feature selection techniques on model performance. However, there is a lack of discussion on how different swarm intelligence methods can improve model performance. This study aims to evaluate and compare the performance of six swarm intelligence algorithms in developing an ML model for CVD prediction.

The main contributions of this study are:

-

This study explored the impact of different swarm intelligence feature selection techniques, including the WOA, CSA, FPA, HHO, PSO, and GA, on ML algorithms for predicting CVD.

-

In order to achieve the established goals, this study carefully selected two highly representative CVD datasets from Kaggle’s official website. Specifically, this study adopted a combined dataset from multiple heart disease studies (covering Cleveland, Long Beach VA, Switzerland, and Hungary), as well as the highly anticipated Framingham dataset. It is worth emphasizing that this study cleverly selected balanced and unbalanced datasets as the analysis objects. This design aims to comprehensively and deeply test the performance of swarm intelligence optimization algorithms when processing different datasets, thereby providing a more solid and reliable basis for its widespread application.

-

Subsequently, this study conducted an in-depth comparison of the key indicators of the six swarm intelligence algorithms in different swarm situations, including the mean, maximum, minimum, and standard deviation of the average running time, fitness, and Cohen Kappa value, as well as the number of feature subsets selected by each algorithm. Through this series of detailed comparative analysis, this study aims to find the best performing algorithm from each data set and determine the best feature subset it generates.

-

Then, this study applied the best feature subsets selected by the best performing algorithms in different data sets to ten different classifiers, including support vector machine (SVM), naive bayes (NB), random forest (RF), extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost), adaptive boosting (AdaBoost), decision tree (DT), k nearest neighbor (KNN), recurrent neural network (RNN), multilayer perceptron (MLP) and long short-term memory network (LSTM).

-

Given that one of the datasets involved in this study had a data imbalance problem, we used multiple comprehensive indicators in the model evaluation phase to ensure the comprehensiveness and accuracy of the evaluation. Specifically, we used five key indicators: accuracy, precision, recall, AUC value, and F1 score to measure model performance comprehensively. To compare and select models more scientifically, we also calculated a comprehensive weighted score by assigning different weights to these different evaluation indicators. Finally, we ranked the model performance according to this weighted score to screen out the model that performed best when dealing with imbalanced datasets.

-

The core achievement of this study is a systematic comparison and in-depth analysis of six swarm intelligence feature selection techniques in selecting optimal features across varying population sizes and dataset types combined with ML for early cardiovascular disease diagnosis.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: Sect. 2 reviews related work, Sect. 3 details the experimental steps, Sect. 4 analyzes and discusses the results, and Sect. 5 concludes the study.

Related works

In previous research, feature selection combined with ML techniques has also been applied to various diagnostic and survival tasks related to CVDs. This section presents an overview of the combined heart disease dataset and the Framingham dataset used in this study, along with a detailed review of key research findings on other heart disease datasets.

The research utilizing the combined heart disease dataset is summarized below. Wadhawan and his team46 proposed an early prediction technique for heart disease (ETCD) that leverages machine intelligence, emphasizing an Optimal Feature Subset Selection Algorithm to identify essential features from various datasets, such as the Cleveland, Hungary, integrated, and Z-Alizadeh Saini datasets. The research notably enhanced the average accuracy of heart disease predictions across these datasets by applying the ETCD technique and employing a range of classifiers, including SVM, KNN, DT, NB, and RF. Ghosh et al.47 developed an effective smart diagnostic framework for heart disease based on the Cleveland dataset, utilizing DT, KNN, and RF. They also examined how various feature sets influence prediction performance. They found that when using the RF classifier and the Relief algorithm to select features, the model reached its peak performance with an accuracy of 98.36%. Cenitta et al.48 presented a metaheuristic approach known as the Improved Hybrid Dolphin Search Optimization Algorithm, which, when combined with the RF classifier, optimized feature selection on the combined heart disease dataset, led to a prediction accuracy surpassing 98%. Atimbire et al.18 employed WOA for feature selection and subsequently applied the XGBoost classifier to the heart disease combined dataset, achieving a remarkable 100% prediction accuracy, powerfully demonstrating the efficiency of metaheuristic algorithms in feature selection.

This section summarizes relevant research using the coronary heart disease dataset collected from the Framingham Heart Study. Mahmoud et al.49 conducted an in-depth investigation into various classification techniques to predict heart disease and related conditions. To thoroughly assess the effectiveness of these predictive models, they employed a 10-fold cross-validation resampling method. The experimental findings demonstrated that the RF model performed exceptionally well in the prediction tasks, achieving an accuracy of 85.05%. In the study by Mienye et al.50, modifications were made to a Weighted Aging Ensemble classifier. The experimental findings on the Framingham dataset reached a classification accuracy of 91%, exceeding the performance of other ML algorithms and related studies. Rahim and his team51 designed and implemented a CVD diagnostic framework named Machine Learning-assisted Cardiovascular Disease Diagnosis (MaLCaDD). The framework first adopted a dual strategy for the data preprocessing stage: it effectively addressed missing values using mean imputation and significantly improved class imbalance in the dataset through Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique. Subsequently, the framework employed feature importance assessment techniques to meticulously select the most influential feature set for diagnostic outcomes. In the classification model construction phase, the framework integrated a Logistic Regression model with a KNN classifier, proposing an ensemble prediction method. Ultimately, validated using the Framingham benchmark dataset, the MaLCaDD framework demonstrated outstanding performance, achieving an accuracy of up to 99.1%. Krishnani et al.52 developed an enhanced preprocessing workflow to predict the likelihood of coronary heart disease accurately. This workflow included handling null values, data resampling, standardization, and normalization, followed by feature classification and model prediction. The experimental results applied to the Framingham dataset showed that the RF classifier attained an accuracy of 96.8%. In the study by Shetgaonkar et al.53, three artificial intelligence-based methods—DT, NB, and Neural Networks—were utilized to predict cardiovascular or heart diseases. All methods were analyzed according to different criteria and adjusted for enhanced accuracy, with the highest performance achieved by the DT model, reaching an accuracy of 98.54%. In the research by Atimbire et al.18, feature selection was performed using WOA on the Framingham dataset, followed by the KNN model, resulting in a successful accuracy of 99.44%, demonstrating the efficiency of this method in CVD prediction.

This section reviews related studies on other heart disease datasets. In the study by Reddy et al.54, they used the Cleveland Heart Disease Dataset of UCI, selected features based on rough set theory, and applied fuzzy logic adaptive GA for classification tasks, ultimately achieving an average classification accuracy of 90%. Goyal55 proposed a feature selection method that combines SVM, artificial neural network (ANN), and DT. This method is based on the Lion Optimization Scheme (LOFS). The ANN model optimized by LOFS was used on the Cleveland heart disease dataset and achieved the best classification accuracy of 90.5%. In the study by Ay et al.56, different feature selection methods were used to optimize the classification performance of the two datasets. Specifically, for the Cleveland dataset, they used the feature selection method FPA to select the optimal features and input these features into the KNN classifier, and finally obtained an F1 score of 99.72%; in addition, for the heart failure dataset collected from the Faisalabad Institute of Heart Disease and the Faisalabad Joint Hospital, they used HHO to select the optimal features and also sent these features into the KNN classifier, and achieved an F1 score of 97.45% in the survival prediction task. Aloss et al.57. applied five different ML algorithms based on the Crow search algorithm to the heart disease dataset and achieved good results.

The literature review concluded that feature selection can improve classifier performance. The algorithm used in this study shows wide application value and potential in this field. However, for the two specific datasets involved in this study, we noticed that related research is relatively scarce. More research is necessary to identify the optimal strategy for feature subset selection optimization. This research is motivated by several vital reasons. First, early identification and intervention of CVD, the leading cause of death globally, are essential for saving lives and improving public health. Timely diagnosis enables healthcare providers to prevent disease progression and enhance patients’ quality of life. Second, understanding the pathogenesis of CVD requires a thorough investigation of how different features impact diagnosis, aiding in the development of accurate models and informing future treatment strategies. Lastly, efficient ML models are a major driving force, as their rapid learning and non-invasive capabilities allow for precise analysis of complex data and early CVD detection, supporting clinical decision-making.

Experimental study

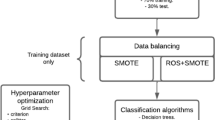

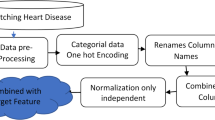

The experimental process described in this study is shown in Fig. 1. Two key datasets were used in this study: one is the heart disease combined dataset from the Kaggle platform, and the other is the well-known Framingham dataset, both of which were used for model training and testing. The entire experimental process started with data preprocessing, and then the six swarm intelligence algorithms, WOA, CSA, HHO, FPA, PSO, and GA, were used to select the best feature subsets; on this basis, we conducted a detailed comparison of the performance of these six feature selection algorithms, aiming to select the most outstanding feature selection algorithm for each dataset. Next, we applied ten different ML techniques, including SVM, NB, RF, etc., to the optimal feature subsets selected for each dataset. Finally, we used multiple evaluation indicators to conduct an in-depth evaluation of the effect of feature selection and the performance of the constructed model.

Datasets

This study utilized two independent datasets for experimental analysis. The first dataset is centered on predicting heart disease risk. It is sourced from the Kaggle platform, combining data from the Cleveland, Long Beach VA, Switzerland, and Hungary heart disease datasets. It contains a total of 14 feature indicators and 1,025 records. In this dataset, the ‘target’ attribute underpins disease prediction, with 0 denoting the absence of disease and 1 indicating its presence. Supplementary Table S1 offers a comprehensive overview of the dataset’s characteristics.

The second dataset, the Framingham dataset, focuses on assessing the risk of coronary heart disease. This dataset includes 16 attributes and 4,240 records, offering a robust data foundation for an in-depth investigation into the risk of coronary heart disease. A thorough overview of the Framingham dataset is available in Supplementary Table S2.

Data preprocessing

Data preprocessing is an indispensable foundation for building high-performance, reliable ML models. It encompasses data cleaning, correction, transformation, and organization, intending to guarantee the dataset’s accuracy, consistency, and validity.

Missing value handling

To address missing values in the dataset, this study employed different imputation strategies based on the variable types (categorical and continuous). The majority filling method is used for categorical variables, which selects the most frequent category in the data set as the filling value. This approach effectively preserves the distribution characteristics of the data and is suitable for categorical data. For continuous variables, the KNN imputation algorithm was introduced. This algorithm identifies the K nearest neighbors by calculating the distances between the missing value sample and complete samples and then estimates and fills the missing values using the weighted average or median of these neighbors. The KNN imputation method leverages the local structural characteristics of the data, enhancing both the accuracy of the imputations and the overall completeness of the dataset.

Data standardization

This study utilized the standardization process of StandardScaler. StandardScaler is a commonly used standardization tool, and its standardization process is illustrated by the following equation (1):

\({\text{\rm X}}\) represents the original feature value, \(\mu\) denotes the mean of the feature, \(\sigma\) indicates the standard deviation of the feature, and \({\text{\rm Z}}\) refers to the standardized feature value. This transformation guarantees that each feature has a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1, normalizing the data distribution and removing the dimensional influences of different features.

Data visualization

Prior to feature selection, this study employed density-based spatial clustering of noisy applications and principal component analysis for dimensionality reduction, followed by analysis using three visualization techniques to better understand the structure of the two datasets.

Heatmap: A correlation heat map is an intuitive tool for showing the strength of positive and negative correlations between features. The embedded histogram offers a glimpse into the strength of the correlation, aiding in the comprehension of the overall data structure and the significance of the features. We can identify closely related feature combinations and independent features through analysis, providing valuable reference information for subsequent feature selection.

Violin plot: The violin plot is a classic tool for visualizing data distribution. It is used to show the shape, position, scalability, and internal structure of feature distribution. This figure intuitively shows the distribution characteristics of the eigenvalues, which helps researchers further understand the distribution characteristics of the data and potential outliers.

Target variable distribution graph: This study uses histograms and density graphs to show the detailed distribution of the target variable. The histogram displays the frequency distribution of the target variable across various value ranges via the area or height of the bars. At the same time, the density graph further refines and enhances this distribution by utilizing a continuous density curve. Collectively, they provide a clear and detailed insight into the distribution characteristics of the target variable, facilitating a more profound comprehension of its statistical properties and possible patterns.

As shown in Figs. 2 and 3, the heat map effectively reveals the multicollinearity problem between features, which is crucial for improving model performance and guiding feature selection. After standardization, the violin plot reveals that most features still have distribution differences, providing an intuitive understanding of data features for subsequent analysis. The target distribution map intuitively shows the potential class imbalance problem in the dataset. It can be seen from sub-graph c of Fig. 2 that the combined dataset is a balanced dataset, and this study uses the fitness value as the objective function; sub-graph c of Fig. 3 shows that the Framingham dataset has a data imbalance problem, so Cohen’s Kappa metric is used as the objective function. In summary, these findings underscore the significance of feature selection in the dataset to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the subsequent analyses.

Feature selection

The core driving force of the feature selection step is to select the feature subset that can best represent the dataset. This study adopts six swarm intelligence feature selection methods to explore this area in depth. In order to effectively alleviate the inherent randomness problems of these algorithms, this study independently implemented ten experiments for each of the above methods for each dataset to ensure the robustness of the results. Furthermore, to deeply analyze the specific impact of population size on algorithm performance, this paper carefully sets three different population sizes: 10, 25, and 50, and the number of iterations is constant at 50 times. In terms of data set division, this study follows the 8:2 ratio principle and divides the data set into two, that is, 80% as a training set and the remaining 20% as a test set. The training set is then input into each feature selection algorithm. Finally, this study summarizes the experimental data, where Table 1 focuses on the experimental results of the combined data set, and Table 2 explicitly explains the Framingham data set. These two tables show in detail the statistical information of the average running time, fitness, and Cohen kappa value (including average value (avg), maximum value (max), minimum value (min) and standard deviation (std)) of the algorithm, and the optimal number of features, and generate box plots of the objective functions of each algorithm running independently under different populations, as shown in Figs. 4 and 5, which provide strong data support for the comprehensive evaluation of the performance of different algorithms under different population sizes in this study.

Whale optimization algorithm

WOA is a heuristic optimization algorithm developed by Mirjalili and Lewis58. It isinspired by the hunting techniques of humpback whales, specifically their unique 'bubble net hunting’ strategy. The algorithm iteratively approaches the global optimal solution by mimicking the whale’s surroundings, spiraling, and random search behaviors. The pseudocode of WOA is detailed in Supplementary Table S3.

Cuckoo search algorithm

CSA is a heuristic optimization algorithm developed by Yang and Deb40, which is inspired by the brood parasitism behavior of cuckoos and incorporates Lévy flights. The CSA mimics the strategies used by cuckoos to find host nests for laying eggs, combined with the random search behavior of Lévy flights, gradually approaching the global optimal solution. CSA is a convenient and efficient method that is widely used in many different fields, including medical applications, image processing, functional testing, data mining, ML and deep learning applications, path planning, and engineering problems59. The pseudocode of CSA is detailed in Supplementary Table S4.

Flower pollination algorithm

FPA is a meta-heuristic algorithm developed by Yang38, simulating the pollination process of flowering plants. In FPA, the algorithm enhances optimization by emulating the natural pollination process. It progressively converges on the optimal solution using Lévy flight random steps and a blend of local and global search strategies. The pseudocode of FPA is detailed in Supplementary Table S5.

Harris hawk optimization algorithm

HHO is an innovative swarm intelligence optimization algorithm introduced by Heidari et al.43, drawn from the cooperative hunting behavior of Harris hawks. These hawks capture and attack prey through a multi-stage hunting process conceptualized as a dynamic optimization process. The algorithm replicates the foraging tactics of Harris Hawks, enabling it to discover optimal solutions for various intricate optimization problems. HHO comprises two primary phases: the exploration and exploitation phases, transitioning from exploration to exploitation based on the prey’s energy function. The pseudocode of HHO is detailed in Supplementary Table S6.

Particle swarm optimization algorithm

The PSO algorithm60 is an evolutionary computing technique used to find the optimal solution in an n-dimensional search space. It simulates the social interaction behavior of particles, allows randomly generated particles to communicate with each other in the search area, remember the best positions of individuals and neighbors, and finally jointly determine the global optimal position. The pseudocode of PSO is detailed in Supplementary Table S7.

Genetic algorithm

GA is an evolutionary algorithm in computer science inspired by the biological process of natural selection and survival of the fittest. The algorithm primarily uses operations like crossover, gene mutation, and selective evolution to optimize the search space, with the goal of finding the global optimal solution for multi-objective optimization problems. The pseudocode of GA is detailed in Supplementary Table S8.

Model training and testing

Once the optimal features are chosen, the data is input into predictive models for training and testing. The models employed in this study consist of traditional ML classifiers such as DT, NB, KNN, and SVM; ensemble learning classifiers including RF, XGBoost, and AdaBoost; along with deep learning classifiers like MLP, RNN, and LSTM.

Support vector machine

SVM was introduced by Boser et al.61 in 1992. Its core concept is to construct an optimal hyperplane as the decision boundary, divide the observations into two categories, and ensure that the distance from the observation points in each category to the boundary is maximized to achieve efficient classification.

Naive Bayes

NB is a Bayesian algorithm combining prior and posterior probability to directly evaluate the probability association between the outcome and the variable. This algorithm requires the input variables to be independent of each other, and its output is an accurate probability value62.

Random forest

RF was proposed by Breiman63. It uses multiple decision trees (weak classifiers) for ensemble prediction and improves prediction performance through independent combination and majority voting principles. As the accuracy of a single tree increases, the overall prediction becomes more accurate, so it is widely used in medical practice.

Extreme gradient boosting

XGBoost is a gradient-boosting algorithm proposed by Tianqi Chen et al.64. It uses multiple classification and regression trees in a serial ensemble and trains them through a forward distribution algorithm. Specifically, the algorithm first fits the data with a tree to get a preliminary prediction and then iteratively trains subsequent trees based on the negative gradient of the loss function (including second-order information). Each iteration uses the prediction error of the previous round for optimization. At the same time, regularization is introduced to control the complexity of the tree. After multiple iterations, the prediction values of each tree are finally summed up to get the final prediction.

Adaptive boosting

AdaBoost is a classic boosting algorithm. Its core is to gradually optimize and select models with better performance through repeated testing, adjustment, and screening. In this process, models with excellent performance will be given higher voting weights, while models with poor performance will be given lower voting weights accordingly. Finally, the voting results of all basic learners are combined to determine the final prediction65. Generally speaking, the data set obtained by the boosting method will have a smaller deviation.

Decision tree

The DT model was first proposed by Hunt et al. in 1966. It is a supervised ML method that combines classification and regression functions. Compared with other models, the principle of the DT model is more intuitive and easier to understand, and the modeling process is relatively simple. In addition, it can accurately analyze and predict big data in a short time and efficiently.

K nearest neighbor

KNN is a relatively intuitive classification algorithm, and its classification results mainly depend on two key factors: the distance function between samples and the choice of parameter k. The core of the algorithm lies in the appropriate selection of k value and a distance metric function to accurately calculate the distance between samples66.

Recurrent neural network

RNN67 is a neural network that introduces recurrent connections. It is specialized in processing sequence data and has memory and time series characteristics. Its core lies in the concept of time steps between hidden layers. At each time step, the input is linked to the hidden state of the previous step, influencing both the current output and hidden state. This recurrent structure enables RNNs to capture temporal dependencies and context within a sequence, making them effective for tasks like natural language processing and speech recognition, especially those requiring contextual understanding.

Multilayer perceptron

MLP68 is a typical structure of ANN. It is composed of three components: an input layer, one or more hidden layers, and an output layer. In these layers, neurons are fully connected through nonlinear activation functions, and the connection between each layer and the next layer is assigned different weights. Each layer’s output is weighted and summed to become the input for the following layer of neurons. MLP is proposed to overcome the limitation that single-layer perceptron cannot handle nonlinear problems.

Long short-term memory

LSTM69 is a variant of RNN specifically designed to process sequential data, including time series, text, and speech. Maintaining its hidden state in a feedback loop allows it to learn and remember long-term and short-term dependencies more efficiently than traditional recurrent neural networks.

Model evaluation metrics

Each classifier is first evaluated using 5-fold cross-validation to assess its ability to generalize. The model is subsequently evaluated using metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC), and the F1 score. The rationale for selecting these evaluation metrics is explained in the following sections.

Accuracy is a metric that assesses how closely the model’s predictions match the actual outcomes, clearly indicating the model’s performance in classification tasks70. Accuracy is a fundamental and commonly used performance metric in ML and statistical classification. Its calculation equation is straightforward, as shown in (2), quantifying the ratio of correct predictions made by the model.

TP (True Positive) refers to cases where both the predicted and actual results are positive; FN (False Negative) refers to cases where the actual result is positive, but the prediction is negative; FP (False Positive) refers to cases where the actual result is negative, but the prediction is positive; TN (True Negative) refers to cases where both the actual and predicted results are negative.

Precision, also called positive predictive value, quantifies the ratio of actual positive cases to the total samples the model labels as positive. In medical diagnosis, high precision is especially crucial because it helps minimize false positives—incorrectly identifying healthy individuals as sick—thereby preventing unnecessary medical interventions and reducing patient stress71. The equation is shown in (3).

Recall, or sensitivity, evaluates the proportion of actual positive cases among all genuinely positive samples. This metric intuitively illustrates the capability to identify true positive cases, expressed as a percentage accurately. Given that high sensitivity means minimizing the chances of missing true positives (individuals who are sick or abnormal), it is considered a crucial evaluation criterion in medical research, with far-reaching implications for early diagnosis of diseases, assessment of treatment efficacy, and formulation of public health strategies. The equation is shown in (4).

AUC measures a classification model’s effectiveness in distinguishing between negative and positive classes. The AUC value is obtained by examining the ROC curve, which describes the relationship between the true positive rate also called recall rate (TRP) and the false positive rate (FPR) for different classification thresholds. The equation for this metric is shown in (5),(6).

The F1 score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall, providing a metric to assess a model’s overall performance, especially in situations involving imbalanced datasets. Precision measures the ratio of true positives among samples predicted as positive, while recall assesses the proportion of true positives that the model accurately identifies. Considering both metrics, the F1 score mitigates biases that may arise from relying on either metric alone; the equation is shown in (7).

Model hyperparameters

This study used grid search to tune hyperparameters for each classifier to optimize model performance. To ensure robustness, a grid search with 5-fold cross-validation was conducted to assess the performance of each hyperparameter combination. The optimal hyperparameters for the ten models used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table S9.

Experimental setup

All experiments are conducted on Python 3.9, and this study runs the experiments on a laptop with a processor of 13th Generation Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-13700H CPU, 32 GB RAM, and Windows 10.

Results and discussions

This section provides a thorough comparison of the six feature selection methods and evaluates the performance of models trained with the optimal feature subsets selected by these methods across various datasets. The analysis aims to highlight the strengths and limitations of each method in dealing with different dataset types and their impact on model training outcomes. The section concludes with a summary of the comparative study.

Comparison of feature selection outcomes across different algorithms

This study systematically examines the performance of six feature selection algorithms on two datasets, aiming to assess the influence of varying population sizes on their performance. The experimental design includes population sizes of 10, 25, and 50, with each algorithm iterated 50 times at each size to ensure the robustness of the results. This study comprehensively considered the average running time of the model, multiple statistical indicators of the value of the objective function (including average, maximum, minimum, and standard deviation), and the number of features finally selected. In order to obtain a more comprehensive performance evaluation, each algorithm was independently run 10 times at specific population size, and box plots for the two data sets were drawn accordingly (as illustrated in Figs. 4 and 5). Figure 4 focuses on the combined dataset and intuitively reveals the following findings: the box plot area of the FPA and PSO algorithms are larger, which means that its performance fluctuates greatly and its stability needs to be improved; in contrast, when the population size is 25, the box plot area of the WOA is the smallest, indicating that this setting has a beneficial effect on its performance; when the population size increases to 50, the WOA box is similar to the population size of 10, both of which are relatively large, indicating that the algorithm has a positive impact when the population size is 25; the areas of the other three algorithms in the figure are similar at different population sizes, so the results need to be further analyzed. Figure 5 is a demonstration of the Framingham dataset. In this dataset, when the population size is 50, the WOA exhibits the smallest box range, which strongly illustrates that a larger population size helps improve the convergence speed and stability of the algorithm. Meanwhile, the HHO reaches the minimum box area when the population size is 50, showing its optimized performance at this specific scale. It is worth noting that for FPA and GA, the box area does not change much with the population size.

In Tables 1 and 2, this study records in detail the average running time, objective function value, and specific number of feature selections of various algorithms under different population sizes. In this study, to evaluate the performance and stability of the algorithm, we performed weighted calculations on the mean (weight 0.7) and standard deviation (weight 0.3) of the objective functions of various algorithms at different population sizes in Table 3. The results indicate that on the combined dataset, CSA achieves the best performance with a population size of 25, yielding a score of 0.69058. In contrast, on the Framingham dataset, WOA performs optimally with a population size of 50, achieving a score of 0.44588. On this basis, this study further comprehensively analyzed the average running time of each algorithm under different population sizes and a minimum number of selected features and made detailed observations and comparisons with box plots. We found that in the combined dataset, when the population size of CSA was set to 25, its performance was relatively stable, and the running time was relatively short, at 441.9 seconds. Under this condition, there are nine features selected by the CSA, including sex, age, thalach (maximum heart rate), restecg (resting electrocardiographic results), fbs (fasting blood sugar), trestbps (resting blood pressure), cp (chest pain type), oldpeak (maximum ST segment decrease caused by exercise), ca (number of blood vessels). In the Framingham data set, the WOA also showed excellent time performance, taking 122.2s. By further analyzing the convergence graph results, this study found that when the population size is set to 50, the performance of the WOA is more stable. At this point, the algorithm selects ten features, which are: age, education, diabp (diastolic blood pressure), currentsmoker (whether you are currently smoking), glucose, BMI (body mass index), sysbp (systolic blood pressure), totchol (total cholesterol), cigsperday (daily smoking), and prevalenthyp (whether you have high blood pressure).

Finally, in Figs. 6 and 7, this study shows the convergence plots of the objective functions of CSA in the combined dataset (the population size is set to 25) and WOA in the Framingham dataset (the population size is set to 50), respectively. These two pictures vividly reveal the dynamic evolution of the algorithm performance: In the combined dataset of Fig. 6, CSA shows amazing efficiency in the initial stage, and the fitness value rises rapidly, indicating that the global exploration activity of the algorithm is very active and effective; in the mid-term stage, most curves tend to be stable and the fluctuations decrease, indicating that the algorithm gradually converges; from the final results, there are certain differences between different runs, but the final fitness values of most runs are close to 0.99, reflecting the good stability of the algorithm. Similarly, in the analysis of the Framingham dataset in Fig. 7, the WOA also followed a similar evolutionary trajectory. In the early stage, the fitness value also achieved a rapid improvement, reflecting the algorithm’s efficient global exploration ability in a complex data environment. Subsequently, the mid-term fluctuations once again proved the flexibility and strategy of the algorithm in local optimization, effectively promoting the algorithm’s extensive search for the global optimal solution. In the later stages, regardless of the dataset, the fitness value of WOA stabilized. This trend clearly shows that the algorithm has successfully approached the global optimal solution. Currently, population evolution has stabilized, and the solution quality remains high, with little to no significant improvement or decline. This indicates that the WOA has successfully identified the optimal or near-optimal solution to the problem after thorough and detailed exploration.

To ensure the reliability of the results, this study gathered the optimal values of the objective function from ten separate runs of each algorithm for statistical verification. Next, to assess the effectiveness of the parameter test, we evaluated the data based on strict criteria, including independence, normality, and homogeneity of variance. In terms of independence, since each algorithm starts from a unique random seed, it ensures that each run produces a unique solution set, so the independence condition is met. For normality evaluation, we applied the Shapiro-Wilk test72 to conduct a detailed analysis of the objective function results of the two data sets and implemented the test for each algorithm separately, and the obtained p-values are summarized in Table 4. After carefully reviewing the data in Table 4, we found that not all samples met the normality condition (the results of non-normal distribution have been marked in bold), so the parameter test is not applicable in this case. In view of this, we chose the non-parametric Friedman test to compare the intra-group performance of each algorithm under different population sizes, and the relevant results have been shown in Table 5. It can be clearly observed from Table 5 that in the combined dataset, except for the PSO algorithm, the other algorithms showed statistically significant differences in the intra-group comparison, while in the Framingham dataset, the intra-group differences were not significant. To further analyze the differences in the results between groups, we used the Mann-Whitney U test for comparison, and the specific results are listed in Table 6. It can be clearly seen from Table 6 that in the combined dataset when the population size is 25, the inter-group comparison between the CSA algorithm and other algorithms showed statistically significant differences; similarly, in the Framingham dataset, when the population size is 50, the inter-group comparison between the WOA algorithm and other algorithms also showed statistically significant differences.

Comparison of model results in different datasets after feature selection

In evaluating the model results for different datasets, this study first employed five performance metrics to comprehensively assess the effectiveness of each model. It is particularly noteworthy that when dealing with the Framingham dataset, this study faced a data imbalance challenge. This imbalance could result in the model over-predicting the majority class and neglecting the minority class if performance is solely evaluated using a single metric (e.g., accuracy), ultimately failing to provide a true and comprehensive assessment of the model’s performance. To avoid this potential bias, this study adopted a more sophisticated strategy: to reasonably weight these indicators. This approach aims to ensure the diversity and balance of the evaluation process, prevent any single indicator from excessively dominating the final evaluation conclusion, and thus achieve a comprehensive and in-depth evaluation of model performance. Considering the data imbalance, this study focuses on the model’s capability to recognize minority class samples. Therefore, in terms of weight allocation, this study reduced the weight of accuracy and adjusted it to 0.1. At the same time, to enhance the consideration of the model’s ability to identify minority samples, this study increased the weights of precision, recall, F1 score, and AUC value, setting them to 0.25, 0.25, 0.25, and 0.15, respectively. Such weight distribution not only reflects the response to the problem of data imbalance but also ensures the comprehensiveness and accuracy of the evaluation system. Finally, this study ranked the models according to the weighted scores mentioned above to provide a more objective and fair evaluation of each model’s actual performance across different datasets. In addition, this study lists the detailed results of different categories of precision, recall, and f1 score indicators of different model results in the two datasets in Supplementary Tables S10 and S11, respectively.

Table 7 presents a comprehensive list of the performance metrics for each model on the combined dataset. In terms of model weight score ranking, the RF, XGBoost, AdaBoost, and KNN models performed well, all achieving the highest weight score of 1, indicating their excellent performance on this dataset. In contrast, the NB model performed significantly worse, with a weighted score of only 0.02, reflecting its relatively low applicability on this dataset. Table 8 lists the model results for the Framingham dataset, where the KNN model stands out with a high weight score of 0.92, becoming the best-performing model on this dataset. The NB model again ranked last with a weighted score of 0.14, indicating that the model has relatively weak predictive power on the Framingham dataset.

Comparative studies

In this section, the study provides a thorough and systematic comparative analysis to comprehensively assess the latest advancements in this research area. This evaluation specifically focused on the combined dataset used in this study and the much-discussed Framingham dataset. In order to intuitively present the analysis results, this study carefully compiled Tables 9 and 10, which summarize the representative research results based on the above datasets. It is worth noting that in the comparison presented in Table 10, both this study and the study by Atimbire et al.18 employed the WOA, and the results from both studies indicated that the KNN model achieved the best performance. However, the results of the KNN model obtained in this study are slightly lower than those of the study by Atimbire et al. In this regard, this study conducted a thorough analysis and concluded that the possible reasons include: first, the computing resources of this study were limited, resulting in only 50 iterations of WOA, while Atimbire et al. conducted 100 iterations; second, in order to specifically evaluate the performance of swarm intelligence algorithms when processing unbalanced data sets, this study did not add special parameters for minority class sample identification in the KNN model, which may also be a key factor leading to low results. In addition, this study also conducted a detailed comparative analysis of the variables in the two data sets. The study found that the variables in the combined data set were mostly objective biochemical indicators, such as fasting blood sugar, resting blood pressure, and resting electrocardiogram results, while the variables in the Framingham data set involved more subjective indicators, such as current smoking status, daily smoking volume, and whether there was a history of hypertension. This study believes that this difference in variable composition may be an important factor affecting the accuracy of diagnosis. Through a recent review of relevant literature, we have discovered a series of objective biochemical indicators that have an important impact on cardiac function, including key proteins that maintain heart health by regulating mitochondrial autophagy (such as Pink1, Parkin, FUNDC1, and BNIP3)73, and calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP)74 that protects the cardiovascular system by inhibiting the aging process of cardiac fibroblasts. In addition, we also noticed that the drug doxorubicin can induce cardiac fibrosis75, thereby impairing cardiac function. Based on these findings, this study speculates that if more such objective biochemical indicators are introduced into the Framingham dataset, such as the content of the above-mentioned key proteins, the level of CGRP, and the history of doxorubicin use, the accuracy of the diagnostic model may be greatly improved, making the research results more reliable and ideal.

Through in-depth comparative analysis with related studies, this study reveals the unique advantages of the CSA when dealing with balanced data sets: even with a relatively small number of iterations (only 50 times), the algorithm can still quickly and accurately locate the global optimal solution. However, when faced with the more complex scenario of an unbalanced data set, the WOA requires more iterations to ensure that it can fully explore and find the optimal solution. This finding enhances our understanding of the WOA’s performance characteristics and offers a valuable reference for its effective application in handling unbalanced datasets.

Conclusion

This study evaluates the performance of six feature selection algorithms on different datasets and studies the impact of different population sizes on algorithm performance. The experimental results show that when the population size is 25 and 50, CSA shows good stability and computational efficiency on the combined dataset, and WOA shows good computational efficiency on the Framingham dataset. Through weighted evaluation indicators, the study found that RF, XGBoost, AdaBoost, and KNN models perform well on the combined dataset, while the NB model performs poorly. On the Framingham dataset, the KNN model performs best, but the results are slightly different from those of Atimbire et al., which may be related to the number of iterations and model parameter settings. Finally, the study concludes that for balanced data, swarm intelligence algorithms can quickly find the global optimal solution, but they perform relatively poorly in unbalanced datasets.

This study has several limitations that deserve further discussion. First, it focuses on the research scope of CVDs. Although in-depth, it limits the wide applicability of the research results in the broad field of biomedicine to a certain extent. Secondly, since multimodal data sets (such as heart sound signals and medical images) were not included in the study, valuable opportunities for a deep understanding of disease mechanisms may have been missed, and further improvements in diagnostic accuracy may have been weakened. Furthermore, in terms of experimental design, the verification process of multiple feature selection algorithms was limited to 50 iterations. This limitation may hinder the full optimization of results and potentially impact their stability, thus restricting the overall evaluation of the algorithm’s performance.

Future research should strive to broaden its research scope and integrate richer and more diverse cardiovascular data sets, especially heart sounds and electrocardiogram signals, to enhance the diversity and representativeness of the data. Increasing the number of data instances is essential for a thorough and accurate evaluation of model performance. Moreover, by thoroughly examining the performance of various swarm intelligence feature selection algorithms across multiple iterations and effectively combining multiple classifiers, the accuracy of early CVD diagnosis can be greatly enhanced, providing a more robust and reliable foundation for clinical intervention.

Accurate CVD screening tools will have a profound impact on policymaking. First and foremost, this tool provides a new response strategy for the global public health system to cope with the increasing burden of cardiovascular disease. By achieving early diagnosis of the disease, timely intervention can be made before the disease worsens, effectively reducing treatment costs and mortality and thereby reducing the overall burden on the medical system. In addition, low-cost diagnostic methods that combine swarm intelligence algorithms with machine learning technology have opened up new horizons for disease prediction and personalized medicine, significantly improving the accuracy and efficiency of CVD management, especially in resource-poor areas. The introduction of big data analysis makes it possible to promote disease screening in these areas widely. However, to ensure that the use of such tools meets ethical standards, strict privacy protection measures must be implemented.

Data availability

Combined dataset https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/johnsmith88/heart-disease-dataset, Framingham dataset https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/aasheesh200/framingham-heart-study-dataset.

References

Mensah, G. A., Roth, G. A. & Fuster, V. the global burden of cardiovascular diseases and risk factors. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 74, 2529–2532 (2019).

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs). https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cardiovascular-diseases-(cvds).

Roth, G. A. et al. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases and risk factors, 1990–2019. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 76, 2982–3021 (2020).

Moghei, M. et al. Funding sources and costs to deliver cardiac rehabilitation around the globe: Drivers and barriers. Int. J. Cardiol. 276, 278–286 (2019).

Tsao, C. W. et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2023 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 147, e93–e621 (2023).

Groenewegen, A., Rutten, F. H., Mosterd, A. & Hoes, A. W. Epidemiology of heart failure. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 22, 1342–1356 (2020).

Zhou, C. et al. A comprehensive review of deep learning-based models for heart disease prediction. Artif. Intell. Rev. 57, 263 (2024).

Cai, Y.-Q. et al. Pitfalls in developing machine learning models for predicting cardiovascular diseases: Challenge and solutions. J. Med. Internet Res. 26, e47645 (2024).

Stamate, E. et al. Revolutionizing cardiology through artificial intelligence—Big data from proactive prevention to precise diagnostics and cutting-edge treatment—A comprehensive review of the past 5 years. Diagnostics 14, 1103 (2024).

Alzubaidi, L. et al. Review of deep learning: Concepts, CNN architectures, challenges, applications, future directions. J. Big Data 8, 53 (2021).

Wang, S., Chen, J., Guo, W. & Liu, G. Structured learning for unsupervised feature selection with high-order matrix factorization. Expert Syst. Appl. 140, 112878 (2020).

Al-Tashi, Q., Abdulkadir, S. J., Rais, H. M., Mirjalili, S. & Alhussian, H. Approaches to multi-objective feature selection: A systematic literature review. IEEE Access 8, 125076–125096 (2020).

Amiriebrahimabadi, M. & Mansouri, N. A comprehensive survey of feature selection techniques based on whale optimization algorithm. Multimed. Tools Appl. 83, 47775–47846 (2023).

Pathan, M. S., Nag, A., Pathan, M. M. & Dev, S. Analyzing the impact of feature selection on the accuracy of heart disease prediction. Healthc. Anal. 2, 100060 (2022).

Islam, M. R. et al. A comprehensive survey on the process, methods, evaluation, and challenges of feature selection. IEEE Access 10, 99595–99632 (2022).

Chen, C.-W., Tsai, Y.-H., Chang, F.-R. & Lin, W.-C. Ensemble feature selection in medical datasets: Combining filter, wrapper, and embedded feature selection results. Expert Syst. 37, e12553 (2020).

Noroozi, Z., Orooji, A. & Erfannia, L. Analyzing the impact of feature selection methods on machine learning algorithms for heart disease prediction. Sci. Rep. 13, 22588 (2023).

Atimbire, S. A., Appati, J. K. & Owusu, E. Empirical exploration of whale optimisation algorithm for heart disease prediction. Sci. Rep. 14, 4530 (2024).

Bommert, A., Sun, X., Bischl, B., Rahnenführer, J. & Lang, M. Benchmark for filter methods for feature selection in high-dimensional classification data. Comput. Statist. Data Anal. 143, 106839 (2020).

Ang, J. C., Mirzal, A., Haron, H. & Hamed, H. N. A. Supervised, unsupervised, and semi-supervised feature selection: a review on gene selection. IEEE/ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinf. 13, 971–989 (2015).

Khaire, U. M. & Dhanalakshmi, R. Stability of feature selection algorithm: A review. J. King Saud Univ. Comput. Inf. Sci. 34, 1060–1073 (2022).

Firdaus, F. F., Nugroho, H. A. & Soesanti, I. A review of feature selection and classification approaches for heart disease prediction. IJITEE 4, 75–82 (2021).

Li, J. et al. Feature selection: A data perspective. ACM Comput. Surv. 50, 94:1–94:45 (2017).

Mahesh, B. Machine learning algorithms—A review. Int. J. Sci. Res. (IJSR) 9, 381–386 (2020).

Sarwar, T. et al. The secondary use of electronic health records for data mining: data characteristics and challenges. ACM Comput. Surv. 55, 33:1–33:40 (2022).

Beskorovainyi, V. V., Petryshyn, L. B. & Shevchenko, OYu. Specific subset effective option in technology design decisions. AAIT 3, 443–455 (2020).

Bach, F. Breaking the Curse of dimensionality with convex neural networks. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 18, 1–53 (2017).

Cohen-addad, V., Kanade, V., Mallmann-trenn, F. & Mathieu, C. Hierarchical clustering: Objective functions and algorithms. J. ACM 66, 26:1–26:42 (2019).

Xu, Y. et al. Enhanced Moth-flame optimizer with mutation strategy for global optimization. Inf. Sci. 492, 181–203 (2019).

Approximation algorithms for NP-hard problems. ACM SIGACT News 28, 40–52 (1997).

Beheshti, Z. BMPA-TVSinV: A binary marine predators algorithm using time-varying sine and V-shaped transfer functions for wrapper-based feature selection. Knowl-Based. Syst. 252, 109446 (2022).

Wolpert, D. H. & Macready, W. G. No free lunch theorems for optimization. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 1, 67–82 (1997).

Malakar, S., Ghosh, M., Bhowmik, S., Sarkar, R. & Nasipuri, M. A GA based hierarchical feature selection approach for handwritten word recognition. Neural Comput. Appl. 32, 2533–2552 (2020).

Altunbey Özbay, F. & Özbay, E. Ses verilerinden cinsiyet tespiti için yeni bir yaklaşım: Optimizasyon yöntemleri ile özellik seçimi. Gazi Üniv. Mühendis. Mimar. Fak. Derg. 38, 1179–1192 (2022).

Salb, M. et al. Cloud spot instance price forecasting multi-headed models tuned using modified PSO. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 36, 103473 (2024).

Purkovic, S. et al. Audio analysis with convolutional neural networks and boosting algorithms tuned by metaheuristics for respiratory condition classification. J. King Saud Univ. Comput. Inf. Sci. 36, 102261 (2024).

Kashef, S. & Nezamabadi-pour, H. An advanced ACO algorithm for feature subset selection. Neurocomputing 147, 271–279 (2015).

Yang, X.-S., Karamanoglu, M. & He, X. Flower pollination algorithm: A novel approach for multiobjective optimization. Eng. Optim. 46, 1222–1237 (2014).

Bacanin, N. et al. Improving performance of extreme learning machine for classification challenges by modified firefly algorithm and validation on medical benchmark datasets. Multimed. Tools Appl. 83, 76035–76075 (2024).

Yang, X.-S. & Deb, S. Cuckoo Search via Lévy flights. in 2009 World Congress on Nature & Biologically Inspired Computing (NaBIC) 210–214 (Coimbatore, India, 2009).

Araújo, L. A. et al. Simulated annealing in feature selection approach for modeling aboveground carbon stock at the transition between Brazilian Savanna and Atlantic Forest biomes. Ann. For. Res. 65, 47–63 (2022).

Sharafaddini, A. M. & Mansouri, N. A Binary chaotic transient search optimization algorithm for enhancing feature selection. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 1–24 (2024).

Heidari, A. A. et al. Harris hawks optimization: Algorithm and applications. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 97, 849–872 (2019).

Yang, X.-S. Bat algorithm: Literature review and applications. Int. J. Bio-Inspired Comput. 5, 141–149 (2013).

Hatta, N. M., Zain, A. M., Sallehuddin, R., Shayfull, Z. & Yusoff, Y. Recent studies on optimisation method of Grey Wolf Optimiser (GWO): A review (2014–2017). Artif. Intell. Rev. 52, 2651–2683 (2019).

Wadhawan, S. & Maini, R. ETCD: An effective machine learning based technique for cardiac disease prediction with optimal feature subset selection. Knowl.-Based Syst. 255, 109709 (2022).

Ghosh, P., Azam, S., Karim, A., Jonkman, M. & Hasan, Md. Z. Use of efficient machine learning techniques in the identification of patients with heart diseases. in Proceedings of the 2021 5th International Conference on Information System and Data Mining 14–20 (Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 2021).

Cenitta, D., Arjunan, R. V. & Prema, K. V. Ischemic heart disease prediction using optimized squirrel search feature selection algorithm. IEEE Access 10, 122995–123006 (2022).

Mahmoud, W. A., Aborizka, P. D. M. & Amer, P. D. Heart disease prediction using machine learning and data mining techniques: Application of framingham dataset. Turk. J. Comput. Math. Educ. (TURCOMAT) 12, 4864–4870 (2021).

Mienye, I. D., Sun, Y. & Wang, Z. An improved ensemble learning approach for the prediction of heart disease risk. Informatics in Medicine Unlocked 20, 100402 (2020).

Rahim, A. et al. An integrated machine learning framework for effective prediction of cardiovascular diseases. IEEE Access 9, 106575–106588 (2021).

Krishnani, D., Kumari, A., Dewangan, A., Singh, A. & Naik, N. S. Prediction of coronary heart disease using supervised machine learning algorithms. in TENCON 2019—2019 IEEE Region 10 Conference (TENCON) 367–372 (2019).

Shetgaonkar, P. & Aswale, S. Heart disease prediction using data mining techniques. Int. J. Eng. Res. Technol. (IJERT) 10, 281–286 (2021).

Reddy, G. T. et al. Hybrid genetic algorithm and a fuzzy logic classifier for heart disease diagnosis. Evol. Intell. 13, 185–196 (2020).

Goyal, S. Predicting the heart disease using machine learning techniques. in ICT Analysis and Applications (eds. Fong, S., Dey, N. & Joshi, A.) vol. 517 191–199 (Springer Nature, Singapore, 2023).

Ay, Ş, Ekinci, E. & Garip, Z. A comparative analysis of meta-heuristic optimization algorithms for feature selection on ML-based classification of heart-related diseases. J. Supercomput. 79, 11797–11826 (2023).

Aloss, A., Sahu, B., Deeb, H. & Mishra, D. A crow search algorithm-based machine learning model for heart disease and cervical cancer diagnosis | request PDF. ResearchGate 860, 303–311 (2022).

Mirjalili, S. & Lewis, A. The whale optimization algorithm. Adv. Eng. Softw. 95, 51–67 (2016).

Ali, W. et al. Introduction to cuckoo search and its paradigms: A bibliographic survey and recommendations. in AI and Machine Learning Paradigms for Health Monitoring System (eds. Malik, H., Fatema, N. & Alzubi, J. A.) vol. 86 79–93 (Springer Singapore, Singapore, 2021).

Eberhart, R. & Kennedy, J. Particle swarm optimization. in Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Neural Networks vol. 4 1942–1948 (Citeseer, 1995).

Boser, B. E., Guyon, I. M. & Vapnik, V. N. A training algorithm for optimal margin classifiers. in Proceedings of the fifth annual workshop on Computational learning theory 144–152 (Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 1992).

Zhang, Z. Naïve Bayes classification in R. Ann. Transl. Med. 4, 241–241 (2016).

Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 45, 5–32 (2001).

Chen, T. & Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A scalable tree boosting system. in Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining 785–794 (ACM, San Francisco California USA, 2016).

Freund, Y. & Schapire, R. E. A decision-theoretic generalization of on-line learning and an application to boosting. J. Comput. Syst. Sci. 55, 119–139 (1997).

Denoeux, T. A k-nearest neighbor classification rule based on Dempster–Shafer theory. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. 25, 804–813 (1995).

Wang, J. & Chankong, V. Recurrent neural networks for linear programming: Analysis and design principles. Comput. Oper. Res. 19, 297–311 (1992).

Singh, J. & Banerjee, R. A study on single and multi-layer perceptron neural network. in 2019 3rd International Conference on Computing Methodologies and Communication (ICCMC) 35–40 (2019).

Hochreiter, S. & Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 9, 1735–1780 (1997).

Chicco, D., Tötsch, N. & Jurman, G. The Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC) is more reliable than balanced accuracy, bookmaker informedness, and markedness in two-class confusion matrix evaluation. BioData Mining 14, 13 (2021).

Sukegawa, S. et al. Multi-task deep learning model for classification of dental implant brand and treatment stage using dental panoramic radiograph images. Biomolecules 11, 815 (2021).

Derrac, J., García, S., Molina, D. & Herrera, F. A practical tutorial on the use of nonparametric statistical tests as a methodology for comparing evolutionary and swarm intelligence algorithms. Swarm Evol. Comput. 1, 3–18 (2011).

Deng, J. et al. The Janus face of mitophagy in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury and recovery. Biomed. Pharmacother. 173, 116337 (2024).

Li, W.-Q. et al. Calcitonin gene-related peptide inhibits the cardiac fibroblasts senescence in cardiac fibrosis via up-regulating klotho expression. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 843, 96–103 (2019).

Xu, A. et al. NF-κB pathway activation during endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition in a rat model of doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. Biomed. Pharmacother. 130, 110525 (2020).

Fajri, Y. A., Wiharto, W. & Suryani, E. Hybrid model feature selection with the bee swarm optimization method and Q-learning on the diagnosis of coronary heart disease. Information 14, 15 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The data for this project is publicly available from Kaggle’s official website, and we would like to thank Kaggle’s R&D team and researchers for sharing the data.

Funding

Research Project of Anhui Educational Committee: Development of a machine learning-based tool to predict amyloid beta positivity in early Alzheimer’s disease (Project No. 2024AH051220). Bengbu Medical University Key Support Project: An Ecological Cohort Study on the Association between Green Vegetation and Stroke Prognosis Based on Big Data Quantum Computing (Project No. 2023bypy015). The National Social Science Fund of China: Research on Barriers to Health Information Acquisition among rural middle-aged residents in a New Media Environment (Project No. 17BGL262).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.B. conducted experiments, analyses, and the original draft; M.X. and T.Z. prepared drawings and tables; X.J., F.W., and X.J. planned, supervised, and contributed to the original draft; X.W. provided funding and prepared the final draft. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bai, T., Xu, M., Zhang, T. et al. Exploration and comparison of the effectiveness of swarm intelligence algorithm in early identification of cardiovascular disease. Sci Rep 15, 4647 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87598-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87598-0