Abstract

The supercritical antisolvent (SAS) method can effectively improve the bioavailability of poorly water-soluble drugs. However, the current supercritical equipment and processes were not fully developed, making industrialization difficult to achieve. Therefore, an externally adjustable annular gap nozzle and its supporting equipment were designed. Curcumin was used as a model drug, ethanol as the solvent, and supercritical carbon dioxide (SC-CO2) as the antisolvent. Building on single-factor experiments, a Box-Behnken Design-Response Surface Methodology (BBD-RSM) was employed to systematically investigate the effects of four process parameters—crystallizer pressure (12–16 MPa), crystallizer temperature (313–323 K), solution concentration (1–2 mg/mL), and CO2/solution flow rate ratio (133–173 g/g)—on the morphology and particle size of curcumin particles. Using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and dynamic light scattering (DLS) analyses, morphologies and mean diameter ranges were examined. To look into how the SAS process affects TML’s chemical and physical characteristics, X-ray diffraction analysis (XRD) and Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) were further performed. Experimental results show that, flow ratio of CO2/solution had the greatest effect of particle size, followed by crystallizer temperature and solution concentration, while crystallizer pressure had the least influence. The optimum process conditions are operational conditions were set with a crystallizer pressure of 15 MPa, crystallizer temperature of 320 K, solution concentration of 1.2 mg/mL, and flow ratio of CO2/solution of 134 g/g, resulting in curcumin submicron particles with an average particle size of 808 nm being obtained. This study demonstrated the feasibility of an externally adjustable annular gap nozzle and its associated equipment in the SAS process, showcasing significant potential for reducing particles size and enhancing the bioavailability of poorly water-soluble drugs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Curcumin is a natural phenolic antioxidant extracted from the ginger plant, belonging to the Zingiberaceae family. It possesses notable anti-inflammatory and anticancer properties with minimal adverse reactions, rendering it highly safe for clinical applications and exhibiting significant global medical interest1. However, its chemical instability and rapid metabolism and excretion in vivo, coupled with low oral bioavailability, greatly limit its clinical utility2. Research has demonstrated that curcumin nano-micron particles hold promise in enhancing its solubility3.

Currently, conventional methods such as mechanical milling4, spray drying5,freeze-drying6, high-pressure homogenization7 and subcritical water treatment8,9,10 are commonly employed in the pharmaceutical industry to obtain nano-sized micron particles. However, these methods often result in non-uniform drug particle sizes, solvent residues, and drug degradation due to high temperature and pressure. Supercritical fluid (SCF) technology, as a green technology, has received great attention from the academic community. It has made great research progress in extraction of essential oil11,12,13,14,15,16,17, seed oil18,19,20, solubility21,22,23, nanoparticle formation24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31, impregnation32,33, optimization and mathematical modeling16,34, polymer synthesis35, etc. Supercritical carbon dioxide (SC-CO2) is the most widely used SCF, with critical conditions (Tc=31.06 °C, Pc = 7.38 MPa) that are easily achievable in production and low equipment requirements. Based on the different roles of supercritical carbon dioxide (SC-CO2) in the preparation of drug micro-particles, the SC-CO2 particle fabrication methods can be categorized into three types: the Rapid Expansion of Supercritical Solution (RESS)26,27, where SC-CO2 acts as a solvent; the Particle from Gas Saturated Solution (PGSS)36,37, where SC-CO2 functions as a solute; and the Supercritical Antisolvent (SAS)24, where SC-CO2 serves as an antisolvent. Due to the unique advantages of SAS technology, the desired particles can be selected by adjusting multiple operating conditions. The morphology and size of particles are influenced by various factors, including nozzle type38,39,40,41, solvent type42, fluid dynamics43, mass transfer in the system44,45, and nucleation and crystallization kinetics38,46,47,48.Under supercritical conditions, the mixing state and supersaturation of the system are two key factors. Typically, adjusting these two factors can yield spherical or amorphous nano-micron particles. However, achieving controlled particle morphology and size remains a challenge.

As the core equipment in particle preparation processes, nozzles significantly influence particle morphology and size. Traditional nozzles suffer from issues such as non-adjustable size, susceptibility to clogging, and non-uniform size distribution, which cannot meet the industrial demand for pharmaceutical microparticles. Therefore, Weiqiang Wang et al.49 proposed a series of large cross-sectional adjustable annular gap nozzle structures, which utilize the gap between two adjustable conical surfaces to form the nozzle, greatly enhancing operational efficiency. Annular gap nozzle achieves adjustable gap sizes by adjusting the relative positions of the cone sleeve and cone core, and ensure that, under equivalent optimal preparation conditions, the cross-sectional area of the annular nozzle structure is nearly ten thousand times larger than that of traditional circular nozzle structures50, significantly increasing throughput. The phenomenon where the fluid flowing in the pipeline undergoes a pressure drop after passing through parts such as valves, slits, and orifices with a sudden reduction in the channel cross-section is referred to as throttling51,52. During the SAS process, when SC-CO2 and the solution pass through the nozzle from a high-pressure environment to a low-pressure environment, a sudden drop in pressure and temperature occurs due to the throttling effect. When reduced to a certain level of pressure and temperature, CO2 can easily form dry ice, leading to nozzle blockage, and the sharp temperature decrease may alter phase equilibrium and solubility, resulting in significant negative effects on particle size and morphology53,54. Therefore, we proposed an adjustable annular gap nozzle, due to the existence of throttling effect, the nozzle throat is often blocked by dry ice, and adjusting the ring gap can avoid this phenomenon. At the same time, compared with the ordinary annular gap nozzle55, its annular gap can be changed at any time, with technological flexibility, to adapt to a variety of working conditions. Thus, the SAS process based on adjustable annular gap nozzle represents another breakthrough in this technology, holding the potential for industrialization.

Nano-micron drugs are a hot research topic in the field of medicine, and SAS, as a cutting-edge technology for the preparation of nano-micron drugs, still has many problems to be solved. Due to the large number of operating parameters that can affect the properties of the product and the interaction between the parameters, a large number of experiments are often needed to obtain the ideal product, and statistical analysis of the experimental results can be performed to obtain the appropriate operating parameter values. Therefore, for the preparation of nano-micron drugs, further discussion and summary of the action mechanism of the operating parameters in the SAS process, and on this basis to simplify the operation of SAS, is an important research direction that SAS can be expanded to industrial application.

In this research, using curcumin as the model drug, ethanol as the solvent, and SC-CO2 as the antisolvent, curcumin particles were prepared. Building on single-factor experiments, a Box-Behnken Design-Response Surface Methodology (BBD-RSM) was employed to systematically investigate the effects of four process parameters—crystallizer pressure (12–16 MPa), crystallizer temperature (313–323 K), solution concentration (1–2 mg/mL), and CO2/solution flow rate ratio (133–173 g/g)—on the morphology and particle size of curcumin particles.

Materials and methods

Materials

CO2 (purity>99.9%, CAS-number:124-38-9) was purchased from Shengxin Gas Co., Ltd. (Jinan, China). Curcumin (purity>99.8%, CAS-number: 458-37-7) was purchased from Mairuida Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). Ethanol (purity>99%, CAS-number: 64-17-5) was purchased from Zhonghao Chemical Co., Ltd. (Jiaxing, China). Tables 1 and 2 provide purity and manufacturer information as well as physical and chemical characteristics of the materials used in this study.

Apparatus and operational procedures

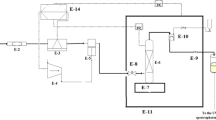

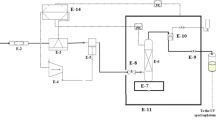

Figure 1 illustrates the schematic and physical diagram of the SAS equipment. The experimental apparatus for preparing curcumin particles using the SAS method (including the external adjustable annular gap nozzle and supporting equipment) was independently developed by our team. The SAS supporting equipment is manufactured by Hua’an Supercritical Extraction Co., Ltd. in Nantong, Jiangsu Province, China. The external adjustable annular gap nozzle is manufactured by Hua cai Science and Technology Test Ground Co., LTD. in Luoyang, Henan Province, China. The device primarily consists of four units: the CO2 supply unit (CO2 cylinder, 1; refrigeration unit, 2; high-pressure plunger pump, 3; preheater, 4; buffer tank, 5); the drug solution delivery unit (container, 6; solvent peristaltic pump, 7); the drug preparation unit (external adjustable annular gap nozzle, 8; crystallizer, 9; separator, 11), and auxiliary devices (back pressure valve, 10; flow meter, 12; electric heating jacket) etc. The manufacturers and detailed specifications of some equipment are shown in Table 3.

Figure 2 shows the physical and schematic diagrams of the nozzle. The nozzle consists of three channels: Channel 1, the inner channel; Channel 2, the middle channel; and Channel 3, the outer channel. According to experimental requirements, the nozzle can independently adjust the spiral ring, driving the core cone, 5 (inner cone sleeve, 6 or middle cone sleeve, 7) to move up and down, thereby changing the size of the annular gap for each of the three channels.

During the experimental procedure, CO2 is first transferred from the cylinder to the refrigeration unit to ensure CO2 remaining in the liquid phase and prevent pump cavitation. Subsequently, CO2 is introduced into the system using a high-pressure plunger pump and heated to the desired experimental temperature via the preheater. It then enters the high-pressure crystallizer through the inner channel of the adjustable annular gap nozzle at a constant flow rate, raising the system to the predetermined pressure. The pressure inside the crystallizer is maintained stable by adjusting the back-pressure valve and the nozzle gap. Simultaneously, an electric heating jacket maintains the temperature of the crystallizer at a constant level. Next, anhydrous ethanol is pumped into the crystallizer through the outer channel of the nozzle at a fixed flow rate for several minutes to stabilize the fluid phase composition inside the crystallizer. Subsequently, a solution of curcumin in ethanol of a certain concentration is continuously injected into the crystallizer until the preparation is complete. After the solution ceases to be injected, CO2 is continuously passed through the system for 90 min to remove residual ethanol from the system as much as possible. Finally, the system is slowly depressurized, and curcumin particles are collected in a powder metallurgy tube equipped with a filter membrane inside the crystallizer, while the ethanol used in the preparation process is recovered through the separator.

Experimental design and statistical analysis

In order to gain deeper insights into this process, an experimental design calculation was conducted to ascertain the optimal operational conditions through the optimization of each variable’s contribution levels to achieve optimal outcomes. BBD-RSM emerges as a robust optimization technique amalgamating experimental design and mathematical modeling, thereby efficaciously reducing the experimentation efforts, formulating mathematical relationships between response variables and factors, scrutinizing the interactive effects among factors, and performing optimization tasks. Guided by preliminary experiments and comprehensive literature review, it was revealed that the crystallizer pressure (A), crystallizer temperature (B), solution concentration (C), and flow ratio of CO2/solution (D) exert significant influences on both particle size and morphology. The behavior of this process conforms to a second-order polynomial function delineated in Eq. (1):

In the equation, Y represents the predicted response (the average particle size), xi and xj denote the independent variables, β0 is the constant term, βi represents the coefficients of the linear terms, βij stands for the coefficients of the interaction terms, and βii denotes the coefficients of the quadratic terms.

Characterizations

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

The morphology of drug particles prepared by SAS method was observed using a scanning electron microscope (SEM, Gemini SEM 300, ZEISS, Germany). Initially, double-sided carbon tape was affixed onto a copper metal stub, and the sample was evenly spread onto the carbon tape. The assembly was then placed into the sputter coater instrument, and vacuum was applied until the vacuum gauge stabilized. The current was adjusted to approximately 10 mA, and the sputter time was set to 20 min. Upon initiating the sputtering process, the sample was coated with platinum. Following the completion of sputtering, the vacuum valve was opened to restore atmospheric pressure, and the sample stub was removed. Subsequently, the sample was transferred to the Gemini SEM 300 instrument, and after achieving full vacuum, scanning observation was performed at a voltage of 15 kV.

Dynamic light scattering (DLS)

Particle size and distribution were measured using a Laser Particle Size and Zeta Potential Analyzer (Nano ZS90, Malvern Instruments Ltd., UK). The particles were dispersed in deionized water, filtered through a 0.22 μm membrane to remove impurities, and then subjected to 5 min of ultrasonic dispersion. Subsequently, measurements were promptly conducted using the analyzer to prevent particle aggregation. Each sample was measured three times at a measurement temperature of 25 °C, and the particle size and distribution were obtained.

X-ray diffraction (XRD)

The X-ray powder diffraction (XRD) pattern of the particles was obtained using an X`Pert3 Powder X-ray Diffractometer (Malvern Instruments Ltd., UK). The particles were loaded onto glass slides and subjected to XRD analysis under the conditions of 40 kV and 40 mA, with Cu as the target material and Kα radiation source, monochromatized using a nickel filter. The scanning step size was set to 0.013°, and the scanning time was 18.87 s, resulting in a diffraction pattern covering a 2θ range of 5–50°.

Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FT–IR)

To investigate the functional group characteristics of the products, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR, IR Tracer 100, Shimadzu, Japan) was used for detection. The KBr and curcumin particle powder were mixed and compressed at a ratio of 100:1 to prepare the sample to be tested, with the scanning wavenumber ranging from 4000 to 400 cm− 1.

Results and discussion

Optimization of SAS process by BBD-RSM

In order to evaluate the feasibility of the experiment, a series of preliminary experiments were conducted. Under the conditions of 14 MPa and 318 K, the SAS-prepared curcumin particles were analyzed and compared with the raw curcumin. The DLS results showed that the average particle size of the raw curcumin was approximately 14.71 μm, while the average particle size of the curcumin particles after SAS treatment was approximately 4.13 μm, with a significant reduction in particle size. Figure 3a,b show the SEM images and size distribution of curcumin before and after SAS treatment, respectively. The results show that the raw curcumin particles are needle- or rod-shaped, with a relatively dispersed size distribution. In contrast, the curcumin particles obtained through the initial SAS process are block- or ball-shaped, with a more concentrated size distribution. This proves the effectiveness of the SAS method in improving the size and shape of curcumin particles.

Based on preliminary experiments and literature reviews, a Box-Behnken experimental design with four factors and three levels was conducted to determine the optimal response of the SAS process. Table 4 presented the levels and numerical ranges of the independent variables. The average particle size of curcumin particles was taken as the response variable, and a total of 29 experimental sets were conducted. The operating conditions and experimental results of each set were listed in Table 4, indicating that the average particle size of curcumin particles ranged from 810 to 4087 nm, at the submicron level. Multivariate regression analysis was performed on the data to obtain a second-order polynomial Eq. (2), which represented the combined influence of the four factors and their interactions on the particle size.

The second-order model ANOVA results based on BBD-RSM were listed in Table 5. Although there are some uncertainties in the process of the experiment that will affect the accuracy of the experimental data. But according to the model ANOVA results shows, the F value of the model was 15.18 > 0.05, and the P value was < 0.0001, indicating a highly significant linear relationship between the response values and the factors in the polynomial model, which suggested a high reliability of the response surface. The lack of fit term had a P-value of 0.0511, which was not significant, signifying a good fit of the model with small experimental errors. The P-values were considered for the significance of the model and the impact of each factor on the response rate, where P < 0.001, 0.001 < P < 0.05, and P > 0.05 represented extremely significant, significant, and insignificant, respectively. Therefore, the effects of the first-order term D, and the quadratic terms A2 and B2 were highly significant in this model. The effects of the first-order term B and C, the interaction terms AB, AD, BC, CD, and the quadratic terms C2 and D2 were significant. The effects of the first-order terms A, and the interaction terms AC and BD were not significant. F-values also assessed the significance of each factor’s impact on the response values in the equation and exhibited a positive correlation, where higher F-values indicated stronger effects. It was evident that flow ratio of CO2/solution (D) was the most significant variable affecting the response, while the crystallizer pressure (A) had the least significant impact. The degree to which the four variables influenced the particle size of curcumin particles was ranked as follows: flow ratio of CO2/solution (D) > solution concentration (C) > crystallizer temperature (B) > crystallizer pressure (A).

One of the crucial steps in determining the suitability of a model is to analyze the residuals. As shown in Fig. 4a, the validated model indicates that the errors are inherent to the model, with residuals uniformly distributed around the fitted line. The actual values depicted in Fig. 4b closely align with the predicted values and exhibit a balanced distribution on both sides. This observation proved a good agreement between the model predictions and experimental data, demonstrating the credibility of the model56,57. The adequacy precision of the model, denoted by Adequate Precision, was 14.06 > 4, implying the model’s reasonability. This consistency between the expected and experimental outcomes underscored the robustness of the statistical analysis and provided substantial support for the experimental conclusions58.

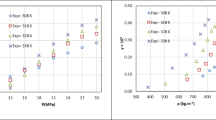

Plotting the interactions of two factors on the response value was achieved by setting two of the four factor levels to “0” and varying the remaining two, resulting in 3D response surface plots and contour plots illustrating the interaction effects. These plots offered intuitive insights into the influence of each factor and their interactions on the response value, with the steepness of the slopes in the 3D plots reflecting the significance of the corresponding factors’ impact on the response value. Meanwhile, the contour plot shapes, resembling ellipses, indicated the strength of interaction between two independent factors58,59,60. Figure 5 depicted the 3D response surface plot of curcumin particle size under the influence of different factors. As observed from Fig. 5c,e,f, the plots involving flow ratio of CO2/solution factor exhibited significant variations in slope compared to other factors. Although Table 6 indicated that the crystallizer pressure was the least significant factor in terms of the main effects, the P-values of the interaction terms A-B and A-D were 0.0008 and 0.0020, respectively, indicating their considerable influence, as evidenced by the substantial changes in slope observed in the 3D response surface plots.

The average particle size under 100 theoretical experimental conditions was predicted through numerical optimization of the quadratic model. The results indicate that the optimal operating conditions are a crystallizer pressure of 14.93 MPa, a crystallizer temperature of 319.86 K, a solution concentration of 1.24 mg/mL, and a flow ratio of CO2/solution of 134.39 g/g, resulting in a predicted average particle size of 789 nm. Considering practical operations, the optimal operating conditions are adjusted to a crystallizer pressure of 15 MPa, a crystallizer temperature of 320 K, a solution concentration of 1.2 mg/mL, and a flow ratio of CO2/solution of 134 g/g. After three repeated experiments, the average particle size of curcumin particles is measured as 803 nm, 825 nm and 796 nm, respectively, with an average of 808 nm and a standard deviation of 15.1, close to the theoretical prediction.

3D response surface plots of particle size under various factor influences. (a) Crystallizer pressure-crystallizer temperature, (b) crystallizer pressure-solution concentration, (c) crystallizer pressure-flow ratio of CO2/solution, (d) crystallizer temperature-solution concentration, (e) crystallizer temperature-flow ratio of CO2/solution, (f) solution concentration-flow ratio of CO2/solution.

Effect of operating conditions of SAS on the particle characteristics

The preparation of submicron particles via the SAS method primarily relied on the nucleation-crystallization mechanism, where nucleation was typically a crucial process that needed to be carefully controlled during crystallization. Direct factors influencing the morphology of the product included the properties of the drug itself, degree of supersaturation, mass transfer rate of CO2 in organic solutions, drug melting, among others. These influencing factors could be controlled by altering various operational conditions to achieve the desired product morphology.

Effect of crystallizer pressure

Based on the optimization process described in previous section, it was found that pressure alone did not significantly affect the particle size. However, the interaction between pressure and other factors had a significant impact on the particle size. Additionally, the study by Kaga et al. indicated that pressure could influence the characteristics of particles61. By comparing Runs 23, 15, and 27, the effect of pressure on particle size was elucidated. SEM images of curcumin submicron particles obtained at 12, 14, and 16 MPa are shown in Fig. 6a–c. It can be observed that with increasing pressure, irregular spherical particles, a mixture of spherical and chunky particles, and irregular chunky particles were successively formed. This phenomenon is attributed to the presence of a supersaturation gradient when the mixing rate is slow, leading to different nucleation rates within the system and the formation of polycrystalline particles47. Moreover, as the pressure increased, the particle size gradually increased. This is because the increase in pressure results in higher density and viscosity of CO2, enhancing its solvation capacity. Consequently, the solubility of the solute in the mixed fluid of SC-CO2 and organic solvent increases, leading to a decrease in system supersaturation during the antisolvent process, which in turn reduces the nucleation rate and increases the particle size. Other studies have also reported the same trend62,63,64.

SEM micrographs of curcumin submicron particles prepared by the SAS process under different conditions. (a) 12 MPa (run 23), (b) 14 MPa (run 15), (c) 16 MPa (run 27); (d) 313 K (run 27), (e) 318 K (run 14), (f) 323 K (run 12); (g) 1 mg/mL (run 9), (h) 1.5 mg/mL (run 13), (i) 2 mg/mL (run 6); (j) 133 g/g (run 3), (k)153 g/g (run 7), (l) 173 g/g (run 15).

Effect of crystallizer temperature

According to the optimization process, it was found that the variation in crystallizer temperature had a significant impact on the particle size of curcumin submicron particles. By comparing Run 27, 14, and 12, the effect of temperature on the particle size of curcumin submicron particles was elucidated. Figure 6d–f shows SEM images of curcumin submicron particles obtained at 313 K, 318 K, and 323 K. It can be observed that at 313 K, the size of curcumin submicron particles was highly uneven, with relatively large chunky particles present. This uneven particle size distribution was attributed to the lower diffusion rate at reduced temperatures, which tended to result in non-uniform solute distribution, leading to irregular particle morphologies and a broader particle size distribution. In contrast, the particles obtained at 318 K exhibited more regular morphologies, as the higher temperature typically facilitated the particle growth process, driving the particles toward a thermodynamically stable state with more uniform shapes. However, the increase in temperature also generally enhanced the solubility of curcumin in SC-CO2, thereby reducing the system’s supersaturation. The reduction in supersaturation likely slowed the nucleation rate, which, in turn, promoted particle growth, resulting in larger particles24. Experiments conducted at high CO2 density (low temperature or high pressure) resulted in larger particles, whereas experiments conducted at low CO2 density (high temperature or low pressure) had the opposite effect. These results demonstrated the relevance of fluid density in designing SAS experiments. However, it was important to recognize that other parameters such as fluid viscosity and solute vapor pressure may also have played a role in influencing particle size and morphology with changes in pressure and temperature65.

Effect of solution concentration

Solution concentration played a significant role in influencing particle size. SEM images of particles obtained from Runs 9, 13, and 6 were presented in Fig. 6g–i. By combining the particle size data from Runs 9, 12, and 6 in Table 2, it was observed that as the solution concentration increased, the particle size initially decreased and then increased. This trend was consistent with previous studies66,67. This parameter had two opposing effects, initially, as the concentration increased, the degree of supersaturation in the system rapidly increased, leading to an increase in the number of primary nucleation and thus a decrease in particle size. However, when the concentration further increased, the degree of supersaturation no longer affected the primary nucleation rate, nor did it further affect the particle size. In this process, higher condensation rates and increased solution viscosity also occurred, resulting in an increase in particle size, uneven distribution, and even the formation of large chunks or flakes particles. The influence of condensation rate was commonly observed in situations with high degrees of supersaturation. A. Montes68 also observed the same trend in their experiments on the precipitation of submicron rutin particles using supercritical antisolvent process.

Effect of flow ratio of CO2/solution

Flow ratio of CO2/solution emerged as the most influential factor affecting particle size. Comparison of the results from Runs 3, 7, and 15 in Table 2 indicated that flow ratio of CO2/solution had a positive effect on particle size. This finding is consistent with previous studies47,69. When flow ratio of CO2/solution increased from 133 g/g to 173 g/g, the particle size increased from 1174 nm to 2908 nm. This phenomenon was attributed to the fact that an increase in the flow ratio reduced the relative content and concentration of the solute in the system, thereby diminishing the driving force required to achieve supersaturation. Consequently, the formation of supersaturation was likely slowed. As illustrated in Fig. 6j–l, higher CO2/solution flow ratios also resulted in significant morphological changes, with the product evolving from irregular spherical structures to irregular massive forms. This transformation was likely due to the reduced solution flow rate, which weakened turbulence and mixing efficiency. Such a decline in mixing uniformity led to heterogeneous solute distribution within the system, causing localized premature supersaturation in some regions while others remained undersaturated. This imbalance adversely affected the processes of nucleation and particle growth. Similar observations were reported in previous studies70,71.

Characterization of particles size distribution

Particles size distributions measured by DLS at different conditions are shown in Fig. 7. To understand the relationship between the particle size and distribution of curcumin, three groups of experiments with the smallest, medium and largest particle sizes were chosen. According to the Table 4, the particle size under these three conditions are respectively 810, 2451 and 4087 nm. It can be seen from Fig. 6 that as the particles size increases, the particles size distribution becomes wider, and the morphology tends to be more blocky68. This is obvious, as the further away from the optimal experimental conditions, the less complete the SAS process is, thus resulting in an uneven size distribution.

Characterization of XRD

In addition to characterizing the morphology of the product, this study also employed XRD to characterize the crystalline phase changes of the product. The examined sample is first exposed to X-ray radiation with a specific wavelength from different angles, and then the diffracted rays are collected and analyzed by the detector. XRD patterns of raw curcumin and curcumin submicron particles obtained via the SAS process under different conditions are shown in Fig. 8. It indicates that the raw curcumin exhibits a high intensity of diffraction peaks, while the position of the characteristic peak of the curcumin submicron particles obtained by SAS process is basically unchanged, but the peak intensity is greatly reduced. This indicates that SAS process may affect the crystallization process of curcumin and reduce its crystallinity, which is conducive to improving the solubility and bioavailability of the compound.

Characterization of FTIR

As depicted in Fig. 9, the FTIR spectra of the curcumin samples before and after the SAS process are presented. It can be observed that the spectra of the treated samples are largely consistent in the positions and intensities of the characteristic peaks with those of the untreated samples. This suggests that the chemical structure and functional groups of curcumin have remained unchanged after the SAS process. Curcumin is a diketone compound polymerized from two aromatic acrylic acids. Curcumin spectrum is rich in absorption bands due to its various functional groups, as is possible to observe in Fig. 8. The following characteristic vibrational bands were identified: stretching vibration of the C=O group at 1629 cm− 1, stretching vibrations of ν(C=O) at 1507 cm− 1, stretching vibration of enol C–O at 1277 cm− 1, C–O–C stretching at 1023 cm− 1, benzoate trans–CH vibration at 959 cm− 1, and alkene CH in-plane bending at 809 cm− 1 72,73.

Conclusions

In this research, curcumin submicron particles with particle sizes ranging from 810 to 4087 nm were successfully prepared using the SAS method on a self-developed experimental apparatus. The effects of crystallizer pressure(12–16 MPa), crystallizer temperature (313–323 K), solution concentration(1–2 mg/mL), and flow ratio of CO2/solution(133–173 g/g) on the size and morphology of curcumin submicron particles were systematically investigated using the BBD-RSM designed response surface methodology. The main conclusions can be drawn as follows: The experimental results indicated that flow ratio of CO2/solution had the greatest impact on particle size, followed by crystallizer temperature and solution concentration, while the influence of crystallizer pressure was minimal. Following BBD-RSM, the optimization operating conditions are: crystallizer pressure of 15 MPa, crystallizer temperature of 320 K, solution concentration of 1.2 mg/mL, and flow ratio of CO2/solution of 134 g/g, which results in curcumin submicron particles with an average particle size of 808 nm. The results of SEM and DLS indicate that the SAS process can ameliorate the morphology of curcumin particles and decrease the particle size. The XRD results reveal a reduction in the degree of crystallinity of the particles. The FTIR results demonstrate that the chemical structure of the particles remains unchanged. This study demonstrated the feasibility of using an external adjustable annular gap nozzle in the SAS process, suggesting the potential application of the SAS method for preparing drug nano-micron particles in equipment featuring external adjustable annular gap nozzles.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyses during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Hani, U. et al. Herbal approach for treatment of cancer using curcumin as an anticancer agent: a review on novel drug delivery systems. J. Mol. Liq. 390, 123037 (2023).

Islam, M. R. et al. Targeted therapies of curcumin focus on its therapeutic benefits in cancers and human health: molecular signaling pathway-based approaches and future perspectives. Biomed. Pharmacother. 170, 116034 (2024).

Yallapu, M. M., Jaggi, M. & Chauhan, S. C. Curcumin nanoformulations: a future nanomedicine for Cancer. Drug Discov. Today. 17, 71–80 (2012).

Meng, H., Zhang, C., Gai, Y., Yu, Q. & Li, Z. Preparation of Ultrashort Composite nanotubes by Twin-Screw Extruder. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 159, 106999 (2022).

Bordón, M. G. et al. Mathematical modeling of the spray drying processes at laboratory and pilot scales for the development of functional microparticles loaded with Chia Oil. Powder Technol. 430, 119018 (2023).

Banožić, M. et al. Physicochemical, structural characterization and evaluation of encapsulated hesperidin from natural sources: comparison of two encapsulation techniques; spray drying and freeze drying. J. Drug Deliv Sci. Technol. 90, 105098 (2023).

Raza, H., Zhou, Q., Cheng, K., He, J. & Wang, M. Synergistic impact of ultrasound-high pressure homogenization on the formation, structural properties, and slow digestion of the starch-phenolic acid complex. Food Chem. 445, 138785 (2024).

Mohammadi, H. S., Asl, A. H. & Khajenoori, M. Experimental analysis and modeling of aprepitant (an antiemetic drug for chemotherapy) solubility in subcritical water with/without co-solvent. J. Supercrit. Fluids. 213, 106356 (2024).

Mohammadi, H. S., Haghighi Asl, A. & Khajenoori, M. Production of pharmaceutical micro and nano particles by subcritical water based technologies: a review. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 85, 104621 (2023).

Share Mohammadi, H., Haghighi Asl, A. & Khajenoori, M. Determination of amiodarone hydrochloride solubility in pure and ethanol-modified subcritical water: experimental data and modeling. J. Mol. Liq. 362, 119679 (2022).

Sodeifian, G. & Sajadian, S. A. Investigation of essential oil extraction and antioxidant activity of Echinophora Platyloba DC. Using supercritical carbon dioxide. J. Supercrit. Fluids. 121, 52–62 (2017).

Sodeifian, G., Azizi, J. & Ghoreishi, S. M. Response surface optimization of Smyrnium Cordifolium Boiss (SCB) oil extraction via supercritical carbon dioxide. J. Supercrit. Fluids. 95, 1–7 (2014).

Sodeifian, G., Saadati Ardestani, N., Sajadian, S. A. & Ghorbandoost, S. Application of supercritical carbon dioxide to extract essential oil from cleome coluteoides boiss: experimental, response surface and grey wolf optimization methodology. J. Supercrit. Fluids. 114, 55–63 (2016).

Sodeifian, G. & Ansari, K. Optimization of ferulago angulata oil extraction with supercritical carbon dioxide. J. Supercrit. Fluids. 57, 38–43 (2011).

Sodeifian, G. & Sajadian, S. A., Saadati Ardestani, N. Optimization of essential oil extraction from launaea acanthodes boiss: utilization of supercritical carbon dioxide and cosolvent. J. Supercrit. Fluids. 116, 46–56 (2016).

Sodeifian, G. & Sajadian, S. A., Saadati Ardestani, N. Experimental optimization and mathematical modeling of the supercritical fluid extraction of essential oil from Eryngium Billardieri: application of simulated annealing (SA) Algorithm. J. Supercrit. Fluids. 127, 146–157 (2017).

Sodeifian, G. & Sajadian, S. A. Saadati Ardestani, N. Evaluation of the response surface and hybrid artificial neural network-genetic algorithm methodologies to determine extraction yield of ferulago angulata through supercritical fluid. J. Taiwan. Inst. Chem. Eng. 60, 165–173 (2016).

Sodeifian, G. & Sajadian, S. A., Saadati Ardestani, N. Supercritical fluid extraction of omega-3 from dracocephalum kotschyi seed oil: process optimization and oil properties. J. Supercrit. Fluids. 119, 139–149 (2017).

Sodeifian, G., Ghorbandoost, S. & Sajadian, S. A., Saadati Ardestani, N. Extraction of oil from Pistacia Khinjuk using supercritical carbon dioxide: experimental and modeling. J. Supercrit. Fluids. 110, 265–274 (2016).

Sodeifian, G., Ardestani, N. S., Sajadian, S. A. & Moghadamian, K. Properties of portulaca oleracea seed oil via supercritical fluid extraction: experimental and optimization. J. Supercrit. Fluids. 135, 34–44 (2018).

Sodeifian, G., Nateghi, H. & Razmimanesh, F. Measurement and modeling of dapagliflozin propanediol monohydrate (an anti-diabetes medicine) solubility in supercritical CO2: evaluation of new model. J. CO2 Util. 80, 102687 (2024).

Sodeifian, G., Sajadian, S. A., Razmimanesh, F. & Ardestani, N. S. A comprehensive comparison among four different approaches for predicting the solubility of pharmaceutical solid compounds in supercritical carbon dioxide. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 35, 2097–2116 (2018).

Sodeifian, G., Usefi, M. M. B. Solubility extraction, and nanoparticles production in supercritical carbon dioxide: a mini-review. ChemBioEng Rev. 10, 133–166 (2023).

Hazaveie, S. M. & Sodeifian, G., Saadati Ardestani, N. Micro and nanosizing of tamsulosin drug via supercritical CO2 antisolvent (SAS) process. J. CO2 Util. 84, 102847 (2024).

Saadati Ardestani, N., Sodeifian, G. & Sajadian, S. A. Preparation of phthalocyanine green nano pigment using supercritical CO2 gas antisolvent (GAS): experimental and modeling. Heliyon 6, e04947 (2020).

Sodeifian, G., Saadati Ardestani, N., Sajadian, S. A. & Soltani Panah, H. Experimental measurements and thermodynamic modeling of Coumarin-7 solid solubility in supercritical Carbon Dioxide: production of nanoparticles Via RESS Method. Fluid Phase Equilib. 483, 122–143 (2019).

Sodeifian, G. & Sajadian, S. A. Solubility measurement and preparation of nanoparticles of an anticancer drug (letrozole) using rapid expansion of supercritical solutions with solid cosolvent (RESS-SC). J. Supercrit. Fluids. 133, 239–252 (2018).

Sodeifian, G. & Sajadian, S. A. Utilization of Ultrasonic-assisted RESOLV (US-RESOLV) with polymeric stabilizers for production of amiodarone hydrochloride nanoparticles: optimization of the process parameters. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 142, 268–284 (2019).

Sodeifian, G., Sajadian, S. A. & Daneshyan, S. Preparation of aprepitant nanoparticles (efficient drug for coping with the effects of cancer treatment) by rapid expansion of supercritical solution with solid cosolvent (RESS-SC). J. Supercrit. Fluids. 140, 72–84 (2018).

Sodeifian, G., Sajadian, S. A. & Derakhsheshpour, R. CO2 utilization as a supercritical solvent and supercritical antisolvent in production of sertraline hydrochloride nanoparticles. J. CO2 Util. 55, 101799 (2022).

Sodeifian, G., Sajadian, S. A., Saadati Ardestani, N. & Razmimanesh, F. Production of loratadine drug nanoparticles using ultrasonic-assisted rapid expansion of supercritical solution into aqueous solution (US-RESSAS). J. Supercrit. Fluids. 147, 241–253 (2019).

Ameri, A., Sodeifian, G. & Sajadian, S. A. Lansoprazole loading of polymers by supercritical carbon dioxide impregnation: impacts of process parameters. J. Supercrit. Fluids. 164, 104892 (2020).

Fathi, M., Sodeifian, G. & Sajadian, S. A. Experimental study of ketoconazole impregnation into polyvinyl pyrrolidone and Hydroxyl Propyl Methyl Cellulose using supercritical Carbon Dioxide: process optimization. J. Supercrit. Fluids. 188, 105674 (2022).

Sodeifian, G., Sajadian, S. A. & Honarvar, B. Mathematical modelling for extraction of oil from dracocephalum kotschyi seeds in supercritical carbon dioxide. Nat. Prod. Res. 32, 795–803 (2018).

Daneshyan, S. & Sodeifian, G. Synthesis of cyclic polystyrene in supercritical carbon dioxide green solvent. J. Supercrit. Fluids. 188, 105679 (2022).

Haq, M. & Chun, B. Microencapsulation of Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and Astaxanthin-Rich Salmon Oil using particles from gas saturated solutions (PGSS) process. Lwt 92, 523–530 (2018).

Pedro, A. S. et al. Curcumin-loaded solid lipid particles by PGSS technology. J. Supercrit. Fluids. 107, 534–541 (2016).

Lazarev, A. V., Semenov, T. A., Belega, E. D. & Gordienko, V. M. Dynamics of expanding gas from supercritical state in conical nozzle and cluster formation. J. Supercrit. Fluids. 187, 105631 (2022).

Lestari, S. D. et al. Effect of Solvent selection and nozzle geometry on Curcuma Mangga Micronization process using supercritical antisolvent: experiment and CFD simulation. Food Bioprod. Process. 123, 367–377 (2020).

Machmudah, S., Winardi, S., Wahyudiono, Kanda, H. & Goto, M. Formation of fine particles from Curcumin/PVP by the supercritical antisolvent process with a Coaxial nozzle. ACS Omega. 5, 6705–6714 (2020).

Fan, M., Li, G., Wang, H. & Lu, Y. Numerical study of hydrogen hydrothermal combustion characteristics in a coaxial nozzle burner. J. Supercrit. Fluids. 183, 105537 (2022).

De Marco, I., Knauer, O., Cice, F., Braeuer, A. & Reverchon, E. Interactions of phase equilibria, jet fluid dynamics and mass transfer during supercritical antisolvent micronization: the influence of solvents. Chem. Eng. J. 203, 71–80 (2012).

Reverchon, E., Torino, E., Dowy, S., Braeuer, A. & Leipertz, A. Interactions of phase equilibria, jet fluid dynamics and mass transfer during supercritical antisolvent micronization. Chem. Eng. J. 156, 446–458 (2010).

Mukhopadhyay, M. & Dalvi, S. V. Mass and heat transfer analysis of SAS: effects of thermodynamic states and flow rates on droplet size. J. Supercrit. Fluids. 30, 333–348 (2004).

Martín, A. & Cocero, M. J. Micronization processes with supercritical fluids: fundamentals and mechanisms. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 60, 339–350 (2008).

Jingfu Jia, W. W. Y. G. Controlled morphology and size of curcumin using ultrasound in supercritical CO2 antisolvent. Ultrason. Sonochem. (2015).

Zhang, Z. et al. Optimization of process parameters for preparation of polystyrene PM2.5 particles by supercritical antisolvent method using BBD-RSM. Sci. Rep. 10, 11187 (2020).

Matos, R. L. et al. Single-step coprecipitation and coating to prepare curcumin formulations by supercritical fluid technology. J. Supercrit. Fluids. 159, 104758 (2020).

Liu, Y., Qu, Y. P. & Wang, W. Q. The structural design of nozzle in outer mixing mode for preparing superfine particles by SCF technology. Adv. Mater. Res. 236–238, 1614–1618 (2011).

Gabor, T., Akin, S. & Jun, M. B. Numerical studies on cold spray gas dynamics and powder flow in circular and rectangular nozzles. J. Manuf. Process. 114, 232–246 (2024).

Mahgerefteh, H., Zhang, P. & Brown, S. Modelling brittle fracture propagation in gas and dense-phase CO2 transportation pipelines. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control. 46, 39–47 (2016).

Martynov, S. et al. Modelling three-phase releases of carbon dioxide from high-pressure pipelines. Process. Saf. Environ. Protect. 92, 36–46 (2014).

Ma, L. et al. Fabrication of emulsions using high loaded curcumin nanosuspension stabilizers: enhancement of antioxidant activity and concentration of Curcumin in Micelles. J. Funct. Foods. 110, 105858 (2023).

Zu, Y. et al. Preparation and characterization of Vitexin Powder Micronized by a supercritical antisolvent (SAS) process. Powder Technol. 228, 47–55 (2012).

Kovalev, O. B., Kovaleva, I. O. & Smurov, I. Y. Numerical investigation of gas-disperse jet flows created by coaxial nozzles during the laser direct material deposition. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 249, 118–127 (2017).

Haque, S. M. Box–Behnken experimental design for optimizing the HPLC method to determine hydrochlorothiazide in pharmaceutical formulations and biological fluid. J. Mol. Liq. 352, 118708 (2022).

Chollom, M. N., Rathilal, S., Swalaha, F. M., Bakare, B. F. & Tetteh, E. K. Comparison of response surface methods for the optimization of an upflow anaerobic sludge blanket for the treatment of slaughterhouse wastewater. Environ. Eng. Res. 25, 114–122 (2020).

Khan, M., Abdulhameed, A. S., Alshahrani, H. & Algburi, S. Development of Chitosan Biopolymer by chemically modified Orange Peel for safranin O dye removal: a sustainable adsorbent and adsorption modeling using RSM-BBD. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 261, 129964 (2024).

Roy, S., Kr Saha, A., Panda, S. & Dey, G. Optimization of Turmeric Oil Extraction in an Annular Supercritical Fluid Extractor by Comparing BBD-RSM and FCCD-RSM Approaches. Mater. Today Proc.. 76, 47–55 (2023).

Duta Lestari, S. et al. Particle micronization of Curcuma Mangga rhizomes Ethanolic Extract/Biopolymer PVP using supercritical antisolvent process. J. Supercrit. Fluids. 146, 226–239 (2019).

Reverchon, E., Adami, R., Caputo, G. & De Marco, I. Spherical microparticles production by supercritical antisolvent precipitation: interpretation of results. J. Supercrit. Fluids. 47, 70–84 (2008).

Rezaee, F. & Ghoreishi, S. M. Saadati Ardestani, N. Precipitation of advanced nanomedicines (Curcumin) using supercritical processing; experimental study, design and optimizing operating conditions. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 99, 105989 (2024).

Esfandiari, N. & Ghoreishi, S. M. Ampicillin nanoparticles production via supercritical CO2 gas antisolvent process. AAPS PharmSciTech. 16, 1263–1269 (2015).

Jafari, D., Yarnezhad, I., Nowee, S. M. & Baghban, S. H. N. Gas-antisolvent (GAS) crystallization of aspirin using supercritical carbon dioxide: experimental study and characterization. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 54, 3685–3696 (2015).

Matos, R. L. et al. Coprecipitation of Curcumin/PVP with enhanced dissolution properties by the supercritical antisolvent process. J. CO2 Util. 30, 48–62 (2019).

Montes, A., Tenorio, A., Gordillo, M. D., Pereyra, C. & De La Martínez, E. J. Screening design of experiment applied to supercritical antisolvent precipitation of amoxicillin: exploring new miscible conditions. J. Supercrit. Fluids. 51, 399–403 (2010).

Montes, A., Pereyra, C. & de la Ossa, E. J. M. Screening design of experiment applied to the supercritical antisolvent precipitation of Quercetin. J. Supercrit. Fluids. 104, 10–18 (2015).

Montes, A., Wehner, L., Pereyra, C. & De La Martínez, E. J. Precipitation of submicron particles of rutin using supercritical antisolvent process. J. Supercrit. Fluids. 118, 1–10 (2016).

Imsanguan, P., Pongamphai, S., Douglas, S., Teppaitoon, W. & Douglas, P. L. Supercritical antisolvent precipitation of Andrographolide from Andrographis Paniculata extracts: Effect of pressure, temperature and CO2 Flow Rate. Powder Technol. 200, 246–253 (2010).

Su, C. S., Lo, W. S. & Lien, L. H. Micronization of fluticasone propionate using supercritical antisolvent (SAS) process. Chem. Eng. Technol. 34, 535–541 (2011).

Zhao, Z. et al. Formation of Curcumin nanoparticles via solution-enhanced dispersion by supercritical CO2. Int. J. Nanomed. 10, 3171–3181 (2015).

Racz, C. et al. Curcumin and whey protein concentrate binding: thermodynamic and structural approach. Food Hydrocoll. 139, 108547 (2023).

Mohan, P. R. K., Sreelakshmi, G., Muraleedharan, C. V. & Joseph, R. Water Soluble complexes of Curcumin with cyclodextrins: characterization by FT-Raman Spectroscopy. Vib. Spectrosc. 62, 77–84 (2012).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support from Natural Science Foundation of China (project No. 21676162).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.W. conceived the experiment and assisted in manuscript preparation. Y.W. and Z.L. conducted the experiment and analyzed the results. F.S. and F.L. optimized the experimental design and assisted in the characterization of curcumin. Y.W. drafted the initial manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., Li, Z., Fayu, S. et al. Preparation of curcumin submicron particles by supercritical antisolvent method with external adjustable annular gap nozzle. Sci Rep 15, 3312 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87787-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87787-x