Abstract

Declining soil health and productivity are key challenges faced by sugarcane small-scale growers in South Africa. Incorporating Vicia sativa and Vicia villosa as cover crops can improve soil health by enhancing nutrient-cycling enzyme activities and nitrogen (N) contributions while promoting the presence of beneficial bacteria in the rhizosphere. A greenhouse experiment was conducted to evaluate the chemical and biological inputs of V. sativa and V. villosa in nutrient-deficient, KwaZulu-Natal (KZN) sugarcane plantation soils. The nutrient concentrations, N and phosphorus (P) cycling bacteria, and extracellular enzyme activities of 5 soils were determined pre-planting and post-V. sativa and V. villosa harvest. Post-harvesting soils had higher pH levels than pre-planting soils. The number of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria increased post-V. sativa and V. villosa harvest, with Arthrobacter, Burkholderia, Paraburkholderia and Pseudomonas as the dominant genera. Acid phosphatase and glucosidase activities increased, with Mvutshini and Mzinto showing the most significant increases (phosphatase: 18.66 to 84.67 for V. villosa, 90.33 for V. sativa; glucosidase: 15.33 to 83 for V. villosa and 105 µmolh− 1g− 1 for V. sativa). In conclusion, V. sativa and V. villosa increased PGPR, pH and enzyme activities, making them viable cover crops for nutrient-deficient sugarcane soils.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Arable land availability is one of the main factors affecting future food supply worldwide1. Arable land per person in 2050 is expected to decrease by 33% from what it was in 19702. Reduced arable land coupled with the ever-increasing world population raises concerns about food security3. In recent years, food insecurity levels have increased steadily in southern Africa and remain a significant developmental problem in the sub-region4. Hendricks5 reported increases in food insecurity rates in most South African households, with food scarcity and poverty being some of the dominant socioeconomic issues in the country6. In 2021, 3.7 million out of 17.9 million households were reported to be food insecure7, with food insecurity affecting most small-scale farming homesteads8,9. Food insecurity is exacerbated by the declining soil fertility and low crop yield experienced by many small-scale growers (SSGs) in the country10. Approximately 70% of South African SSGs residing in rural areas rely on subsistence farming as their source of livelihood11.

Sugarcane is the main cash crop cultivated by SSGs in KwaZulu-Natal (KZN)12. The sugar industry, primarily rural-based, plays a crucial role in supporting these SSGs by generating income and aiding in poverty alleviation and food security12. However, SSGs have been experiencing a decline in productivity12, primarily due to the intensive farming practices employed for cane production13. Small-scale growers practice continuous cultivation and monoculture because of land limitations, practices that have been reported to result in land degradation and declining soil health and fertility13. This is due to the loss of the soil’s organic matter, breakdown of the soil structure, soil acidification and nutrient leaching14. Furthermore, high-yield intensive farming systems often rely on the application of extensive amounts of chemical fertilisers. While fertilisers are crucial in enhancing crop productivity, their misuse or overapplication can lead to environmental degradation and pollution. Additionally, the cost of these chemical amendments can be too costly for poor, resource-limited SSGs10. Increased fertiliser inputs do not guarantee fertility and productivity, as a significant portion of the fertiliser is lost through leaching and runoff15,16. Therefore, soil fertility management practices that sustainably improve soil health and increase production by SSGs are required to mitigate food insecurity and poverty.

Vicia species have been reported to be green manure alternatives in sustainable agricultural systems17,18. Vicia species can effectively enhance soil fertility when used as cover crops by fixing atmospheric N and returning it to the soil through N transfer19. The success of Vicia species can be attributed to their association with diverse microorganisms that benefit the plants’ development20. Ibañez et al.21 suggested that Vicia species foster a substantial community of rhizobial bacteria, promoting the ecosystem function of the bacteria as plant growth promoters. Vicia villosa and V. sativa have been reported to improve acid phosphatase activities and promote soil physical and chemical properties, thereby increasing crop yields and quality22.

Incorporating V. sativa and V. villosa as green manure between sugarcane planting cycles can offer multiple benefits without reducing land availability for sugarcane cultivation. Introducing these legumes enhances crop diversity21, suppressing detrimental soil microbes23 and diversifying the root exudates released by the plant roots into the soil24. While several environmental conditions, such as decreased soil pH and reduced nutrient availability, can limit the activities of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR), the root exudates from these cover crops can enhance PGPR functions by improving the physiochemical properties of the soil25, promoting soil enzyme activities24. Additionally, incorporating these legumes reduces the need for nitrogen (N) amendments by providing N to subsequent crops through N deposition and N transfer26. This process offers a cost-effective alternative to synthetic fertiliser, benefitting resource-limited SSGs. When these plants are eventually incorporated into the soil as green manure, they can release the stored N into the soil27, introducing organic matter, increasing resistance to biological degradation and facilitating a longer and deeper carbon for the next crop28.

Although the utilisation of V. sativa and V. villosa as green manure and cover crops is a growing practice in many agroecosystems29,30, its biological and chemical contribution to sugarcane farming systems in South Africa is unknown. In particular, little is known about the actual effects of the legumes on crop rhizospheres, including their implications for soil dynamics and nutrient cycling in croplands. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the chemical and biological contributions of V. sativa and V. villosa to small-scale KZN sugarcane soils. Additionally, the study seeks to examine how the soil conditions influence the growth physiology and nutrient assimilation rates of V. sativa and V. villosa cover crops. The objectives of the study are to isolate and identify nutrient-cycling bacteria, their associated enzymes and soil chemical characteristics in sugarcane soils collected from five different sugarcane plantation sites pre-planting and post-V. sativa and villosa harvest. Understanding the growth physiology of V. sativa and V. villosa in the different plantation soils will help quantify the N and P accumulated by the legume, which will facilitate the biomass residue management of the crop. We hypothesize that (i) the cultivation of Vicia plants in soils leads to an increase in the population and activity of N-fixing and phosphorus-solubilizing bacteria, which in turn enhances the availability of these nutrients, thereby improving soil fertility and promotes the growth of subsequent crops; and (ii) the cultivation of Vicia plants in acidic soils induces a significant increase in soil pH and basic cation concentrations through root exudate-mediated alterations in soil chemistry, thereby creating more favourable conditions for the growth of sugarcane and other acid-sensitive crops.

Materials and methods

Soil collection sites description

Soil collection sites in the Northern and Southern KZN (the map was created on the 27 June 2024 using Google Earth https://earth.google.com/web, where GPS coordinates were entered as placemarks at the specified soil collection sugarcane plantation sites).

Five rain-fed sugarcane plantation sites were selected for this study as presented in Fig. 1. Soils were collected from these small-scale plantations, which are located at different geographical locations along the north and south coast of KZN. These sites rely heavily on chemical amendments, such as fertilisers and pesticides, to support crop growth31. The northern KZN plantation sites included Mvutshini (28°50’52.9”S,32°00’09.0”E), Mpembeni (28°51’25.7”S,31°58’19.4”E), and Gingindlovu (28°56’29.3”S,31°34’58.9”E) (Fig. 1). The southern KZN plantations, Hibberdene (30°35’37.1214”S,30°31’30.2916”E) and Mzinto (30°16’41.0262”S,30°39’47.9658”E), were located in the South Coast (Fig. 1). Northern KZN is an austral summer rainfall region with a subtropical climate that is warm and humid with an average annual rainfall of up to 900 mm and cold in winter with 90–150 frost days a year32. The South coast of KZN is characterised by a subtropical climate with warm temperatures, mild winters, high humidity, highly intense thunderstorms and generous summer rainfall ranging between 650 and 1000 mm32. From each site, the experimental soils, classified as sandy soils (80–90% sand and 7–13% clay content) with pH levels ranging between 4 and 6, were collected from 20 random points of the plantation at a depth of 10–20 cm, where microbial nutrient cycling activities occur, using a Dutch auger. Pre-planting, the soils for enzyme activity assays, bacterial extraction and identification experiments were collected and packaged into sterile plastic bags. The soils were then immediately placed on ice during transportation and stored at 4 °C before analysis.

Experimental setup, growth conditions, and soil chemical analysis

Vicia sativa and V. villosa seeds used in this study were obtained from AGT Foods Africa, Marji Mizuri farm, KwaZulu-Natal. The seeds were handled as per Plant Improvement Act 53 of 1976, Regulations Relations to Establishment, Varieties, Plant And Propagation Material. The seeds were surface sterilised by immersion in ethanol (80%), rinsed and then immersed in bleach followed by ten consecutive rinses in distilled water. Further, seeds were germinated by soaking in warm water overnight to stimulate germination and then transferred into petri dishes lined with moist, sterile filter paper and stored in the dark for four days at room temperature. After germination, the seeds were planted at 1–2 cm depths in 10 cm diameter pots filled with soil from the different plantations. The experiment was a completely randomised design with the plantation sites as treatments. Each treatment had 10 replications per site per species, resulting in a total of 100 experimental pots. These pots were randomly assigned to positions within the greenhouse and rearranged three times a week throughout the experiment to minimise positional effects such as light and temperature. The experimental trials were conducted in the greenhouse at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, Westville campus, School of Life Sciences building, South Africa. The average night and day temperatures in the greenhouse ranged from 11 to 15 °C and 30–35 °C, respectively. The soil in the pots was maintained at field capacity. The surface was covered with sterile beams to prevent air contamination. Watering was performed weekly using sterile water applied through a watering pipe. Every ten days, the pots in the glass house were re-randomised to avoid border effect. Initial and final harvesting were conducted 14 and 45 days after seedling emergence. The initial and final harvesting was required for the growth, nutrient assimilation, and utilisation calculations. In each harvest, 10 plants were carefully uprooted, rinsed with distilled H2O to remove the soil, separated into roots, stems and leaves, and dried at 65 °C until a constant weight was reached. The plant dry weights (DW) were recorded, and dried material was ground using a mortar and pestle.

The ground plant material was then sent for carbon (C) and N isotope analysis at the Archaeometry Department at the University of Cape Town, South Africa, and P analysis at the Central Analytical Facilities of Stellenbosch University, South Africa. Post-harvest, the soils were transferred into sterile plastic bags and stored at 4 °C to be used for nutrient analysis, enzyme activity assays, and bacterial extraction and identification. For total soil nutrient analysis, three-kilogram (kg) soil samples from each plantation (initial and post-harvest) were air-dried, sieved through a 2 mm sieve, and sent to the South African Sugarcane Research Institute (SASRI) Fertiliser Advisory Services (FAS) for pH, exchange acidity, total cations, primary, secondary and micronutrients analysis.

Soil bacterial extraction

Three-fold soil serial dilutions were conducted in soils before planting and after harvesting to reduce bacterial concentrations, facilitating the isolation of distinct colonies. Briefly, 10 g of soil sample (n = 3) were diluted in 100 ml of autoclaved distilled water under sterile conditions. The dilutions were then transferred into selective media plates by inoculating each plate with 100 µl of the dilution. Jensen media plates were used to grow N-fixing bacteria, while tricalcium phosphate and Simmons citrate plates were used to grow P-solubilising and N-cycling bacteria, respectively. The media plates were incubated at 30 °C and allowed to grow for 3 to 7 days. Thereafter, single colonies were distinguished according to colour and size and sub-cultured into sterile, separate media plates to form pure colonies/cultures. The bacteria were extracted and identified from all soils pre and post-V. sativa and V. villosa harvest.

Bacterial amplification and identification

Pure colonies/cultures obtained from repeated streaking were amplified using a colony PCR where pure bacterial colonies were amplified using the 63F (5’- CAGGCCTAACACATGCAAGTC − 3′) and 1387R (5′- GGGCGGTGTGTACAAGGC − 3′) primers. A T100 Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad, USA) was used for amplification with the initial denaturation at 94 °C for 2 min, 30 cycles of denaturation at 92 °C for 30 s, annealing at 56 °C for 45 s and elongation at 75 °C for 45 s. with the final elongation at 75 °C for 10 min. The PCR products were resolved on 1.0% (w/v) agarose gels (Seakem) and visualised after staining. Positive amplicons were sent for sequencing at Inqaba Biotech Pty. Ltd., Pretoria, South Africa. Thereafter, the sequences were edited and compared against the GenBank database. Homologues were identified using the BLASTN program at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) (accessed 27 December 2023).

Soil enzyme activity analysis

β-Glucosidase and Acid phosphatase activity

The soil β-Glucosidase and acid phosphatase activity (nmolh− 1g− 1) was determined using the fluorescence-based method adapted from Jackson et al.33 on all soils pre and post- V. sativa and V. villosa harvest. Briefly, 10 g of soil sample (n = 3) were homogenised in 100 ml of dH2O at low speed for 2 h. An appropriate MUB substrate, bicarbonate buffer (100 mM) and a 4-Methylumbelliferone standard (100 µM) were prepared. The different solutions were then transferred into 96-well microplates and incubated for 1 h at 30 °C; 0.5 M of NaOH was used to stop the reaction. MUB-phosphatase substrate and 4-MUB-glucopyranoside substrates were used for acid phosphatase and β-Glucosidase activities, respectively. The buffer and standard had their pH adjusted to 5 for the acid phosphatase activity. The fluorescent absorbance was measured at 450 nm using an Apex Scientific microplate reader (Durban, South Africa).

Nitrate reductase activity

The nitrate reductase activity was determined using the method adapted from Bruckner et al.34 on all soils pre and post-V. sativa and V. villosa harvest. Briefly, 5 g of soil sample (n = 3) were mixed with 4 ml of 0.9 mM 2.4 DNP, 1 ml of 25 mM KNO3 and 5 ml of autoclaved distilled water in a conical flask wrapped with foil to prevent light penetration. The mixture was mixed vigorously before incubation for 24 h at 30 °C. After incubation, 10 ml of 4 M KCl was added to each sample, mixed, and passed through Whatman no. 1 filter paper. The enzyme activity was initiated by adding 2 ml of the filtrate into 1.2 ml of 0.19 M of ammonium chloride (pH ~ 8.5) and 0.8 ml of the colour reagent (1% sulphanilamide in 1 N HCl and 0.2% N-(1-naphthyl) ethylenediamine dihydrochloride (NEDD). The sample was then incubated at 30 °C for 30 min. After that, the absorbance was measured at 520 nm using an Agilent Cary 60UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The amount of nitrite released into the medium was expressed as 0.1 µmolh− 1g− 1.

Plant nutrition

Calculation of percentage nitrogen derived from the atmosphere (%NDFA)

Nitrogen isotope analyses were conducted at the Archeometry Department, University of Cape Town, South Africa. The isotopic ratio of N was calculated as δ = 1000‰ (Rsample/ Rstandard), where R is the molar ratio of the heavier to the lighter isotope of the samples and standards as described by Farquhar et al.35. Between 2.100 and 2.200 mg of each milled sample were weighed into 8 mm x 5-mm tin capsules (Elemental Micro-analysis, Devon, UK) on a Sartorius microbalance (Goettingen, Germany). The samples were then combusted in a Fisons NA 1500 (Series 2) CHN analyser (Fisons Instruments SpA, Milan, Italy). The N isotope values for the N gas released were determined on a Finnigan Matt 252 mass spectrometer (Finnigan MAT GmbH, Bremen, Germany), which was connected to a CHN analyser by a Finnigan MAT Conflo control unit. Three standards were used to correct the samples for machine drift, namely, two in-house standards (Merck Gel and Nasturtium) and the IAEA (International Atomic Energy Agency) standard (NH4)2SO4.

%NDFA was calculated according to Shearer and Kohl36, as follows:

%NDFA= \(\:100\left(\frac{{\delta\:}^{15}{N}_{reference\:plant}-{\delta\:}^{15}{N}_{legume}}{{\delta\:}^{15}{N}_{referece\:plant}-B}\right)\);

Where the reference plant was non-nodulated V. sativa or V. villosa, planted 2 weeks later than the experimental plants and grown under the same glasshouse conditions using 500 mM N in a Long Ashton nutrient solution (25% strength). The B value is the d15N natural abundance of the N derived exclusively from biological N-fixation of nodulated V. sativa or V. villosa. The seeds were germinated in the natural inoculum, and thereafter, the seedlings were grown with N-free 25% strength Long Ashton nutrient solution in sterile-sand culture. The B-value of V. sativa was determined as − 2.58. and that for V. villosa as -2.36.

Specific N/P absorption rate (SNAR/SPAR)

The net N/P absorption rate per unit root DW was calculated according to Nielsen et al.37 using the plant’s total N/P content.

SNAR= \(\:({N}_{2}-{N}_{1}/{t}_{2}-{t}_{1})\times\:\left(({\text{log}}_{e}{R}_{2}-{\text{log}}_{e}{R}_{1})/({R}_{2}-{R}_{1})\right)\)

SPAR= \(\:({P}_{2}-{P}_{1}/{t}_{2}-{t}_{1})\times\:\left(({\text{log}}_{e}{R}_{2}-{\text{log}}_{e}{R}_{1})/({R}_{2}-{R}_{1})\right)\)

Where N2 and N1 are the final and initial N, respectively; P2 and P1 are the P content, t is the duration of plant growth, and R is the root. dry weight (mg N g− 1 root DW day− 1).

Specific N/P utilisation rates (SNUR/SPUR)

The total N/P were used to calculate the specific N/P utilisation rate (g DW mg− 1N/P day− 1) according to Nielsen et al.37.

SNUR= \(\:({W}_{2}-{W}_{1}/{t}_{2}-{t}_{1})\times\:\left(({\text{log}}_{e}{N}_{2}-{\text{log}}_{e}{N}_{1})/({N}_{2}-{N}_{1})\right)\)

SPUR= \(\:({W}_{2}-{W}_{1}/{t}_{2}-{t}_{1})\times\:\left(({\text{log}}_{e}{M}_{2}-{\text{log}}_{e}{M}_{1})/({M}_{2}-{M}_{1})\right)\)

Where W, N, P and t represent the plant DW, total N content, total P content and the duration of the plant growth, respectively.

Relative growth rate (RGR)

The relative growth rate was calculated using the method by Agren and Franklin38:

RGR= \(\:\left[(\text{ln}{W}_{2}-{W}_{1})/{t}_{2}-{t}_{1}\right]\)

Where W denotes the dry plant weights accumulated from the initial (W1) and final (W2) harvest and t is the time for plant growth.

Root: shoot ratio

The root: shoot ratio was calculated using the root biomass per shoot biomass of the plant.

Root: shoot= \(\:{D}_{R}/{D}_{S}\)

Where DR is the dry weight of the root while DS is the dry weight of the shoot.

Statistical analysis

R- studio (R version 4.4.2) was used for all analyses where soil nutrition (pre- and post-planting and harvest), soil enzyme activities (pre- and post-harvest) were examined using the analysis of variance (two-way ANOVA). The growth kinetics, plant biomass and plant mineral nutrition of V. sativa and V. villosa were examined using the analysis of variance (one-way ANOVA). A Tukey multiple comparisons post hoc test was conducted when significant results were observed in the ANOVA (p < 0.05). The assumptions for normal distribution were tested using the Shapiro-Wilk test, while the assumption for homogeneity of variance was tested using Levene’s test (car package ( Fox J, Weisberg S (2019). An R Companion to Applied Regression_ Third edition. Sage, Thousand Oaks CA. https://www.john-fox.ca/Companion/.)). A non-parametric (Kruskal-Walli’s test) alternative was used when the assumptions were not met in the One-Way ANOVA. The ART method for non-parametric factorial analysis was conducted using the ARTool package (Kay M, Elkin L, Higgins J, Wobbrock J (2021). ARTool: Aligned Rank Transform for Nonparametric Factorial ANOVAs. doi:https://zenodo.org/records/4721941, R package version 0.11.1, https://github.com/mjskay/ARTool.) and emmeans package ( Lenth R (2024). emmeans: Estimated Marginal Means, aka Least-Squares Means. R package version 1.10.5, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=emmeans.) when the assumptions were not met in the Two- Way ANOVA.

Results

Soil chemical analysis

The soil collection sites and species used had significant, independent effects on the soil N(p < 0.001). There was a significant interaction effect between the species used and the collection sites on the soil N (p < 0.001). The soil N concentrations pre-planting significantly differed from the soil N concentration post-V. sativa (-estimate= -27.9, p < 0.001) and V. villosa (estimate = 17.1, p < 0.001) harvest, with significant differences recorded between the species (estimate= -10.8, p < 0.001). There was a slight, significant increase in soil N concentrations post-V. villosa harvest in Mvutshini and no significant differences in the remaining sites (Table 1). The soil N concentration decreased post-V. villosa harvest in Mpembeni. The soil collection sites and species used had significant independent (p < 0.001) and interaction effects (p < 0.001) on the soil P concentrations. The soil P concentrations pre-planting differed significantly from the soil N concentrations post-V. sativa (estimate= -27.1, p < 0.001) and V. villosa (estimate = 14.9, p < 0.001) harvest, with the two species showing significant differences (estimate= -12.1, p < 0.001). There was a significant decrease in P concentrations in Gingindlovu post-V. villosa harvest, and in Mpembeni and Hibberdene post-V. sativa harvest (Table 1). The soil collection sites and species used had significant, independent (p < 0.001) and interaction effects (p < 0.001) on the soil potassium (K) concentrations. There was no significant difference between the soil K concentration pre-planting and post-harvesting V. sativa (estimate = 4.87, p = 0.57) and V. villosa (estimate = 11.67, p = 0.05), however, there was a significant difference in soil K concentrations post-harvesting the two species (estimate = 16.53, p < 0.004).

The soil collection sites had a significant, independent effect on the soil Ca (Df = 4, F = 103.11, p < 0.001), Mg (Df = 4, F = 67.19, p < 0.001), pH (Df = 4, F = 79.28, p < 0.001) and exchangeable acidity (Df = 4, F = 44.44, p < 0.001). Additionally, there was a significant, interaction effect between the species used and the collection site on the soil Ca (Df = 8, F = 2.96, p = 0.014), Mg (Df = 8, F = 8, F = 2.45, p < 0.001), pH (Df = 8, F = 17.46, p < 0.001) and exchangeable acidity ((Df = 8, F = 13.63, p < 0.00). The soil Ca concentrations pre-planting significantly differed from soil Ca concentrations post- V. sativa (estimate = 26.60, p < 0.001) and V. villosa (estimate= -17.8, p < 0.001) harvesting, with the Ca concentrations showing significant differences between the two sites (estimate = 8.80, p = 0.015). There was an increase in the Ca concentrations across all plantation soils, although no significant differences were recorded (Table 1). Similar trends were recorded in the soil Mg, where Mg concentrations increased across all plantation sites, but no significant differences were recorded (Table 1). The soil pH increased across all sites post-harvesting, with significant differences recorded in Mvutshini and Gingindlovu and in Mpembeni under V. sativa. The soil pH recorded pre-planting significantly differed from the soil pH post-V. sativa (estimate = 26.33, p < 0.001) and V. villosa (estimate= -18.67, p < 0.001) harvesting. The exchangeable acidity pre-planting significantly differed from the exchangeable acidity recorded post-V. sativa (estimate= -13.9, p < 0.001) and V. villosa (estimate = 25.3, p < 0.001) harvest with significant differences recorded in Mvutshini, Mpembeni and Gingindlovu under both species (Table 1).

Bacterial abundance

Vicia sativa and V. villosa did not nodulate across all plantation soils. A total of 16 bacterial strains were isolated pre-planting, compared to 31 isolated post-V. sativa harvest and 27 post-V. villosa harvesting (Fig. 2 and supplementary Table 1). Pre-planting, six bacterial strains were isolated from Mvutshini (1 N-fixing; 1 phosphate solubilising and N-cycling; 1 N-cycling; 3 N-fixing and phosphate solubilising). The number of bacterial strains increased to seven post-V. sativa harvest (1 N-cycling; 4 N-fixing and phosphate solubilising; 2 N-fixing, phosphate solubilising and N-cycling) and five post-V. villosa harvesting (3 N-fixing and phosphate solubilising, and 2 phosphate solubilising, N-fixing and N-cycling). In Mpembeni, five bacterial strains were isolated pre-planting (1 phosphate solubilising; 3 N-fixing and phosphate solubilising; 1 phosphate solubilising, N-fixing and N-cycling). The number of isolated strains increased to eight (2 N-fixing, phosphate solubilising and N-cycling, and 6 N-fixing and phosphate solubilising) post-V. sativa harvest and eight N-fixing and phosphate solubilising strains post-V. villosa harvest. Two N-fixing, phosphate solubilising and N-cycling bacterial strains were isolated from Mzinto pre-planting, which increased to six (2 phosphate solubilising, N-fixing and N-cycling; 1 phosphate solubilising and N-cycling; 3 N-fixing & phosphate solubilising) post-V. sativa harvest and four (1 phosphate solubilising, N-fixing and N-cycling, and 3 N- fixing and phosphate solubilising) bacterial strains post-V. villosa harvest. Pre-planting, two bacterial strains (1 phosphate solubilising and 1 N-fixing and phosphate solubilising) were isolated from Hibberdene, which increased to five (2 phosphate solubilising and N-fixing; 1 N-cycling and phosphate solubilising; 1 N-cycling; 1 phosphate solubilising) bacterial strains post-V. sativa and harvesting and five phosphate solubilising, N-fixing and N-cycling bacterial strains isolated post-V. villosa harvest. One phosphate solubilising and N-cycling bacterial strain was isolated from Gingindlovu pre-planting compared to five (2 phosphate solubilising, N-fixing and N-cycling; 1 N-fixing; 2 N-fixing and phosphate solubilising) isolated post-V. sativa harvest and five (1 N-fixing, phosphate solubilising and N-cycling, and 4 N-fixing and phosphate solubilising) bacterial strains isolated post-V. villosa harvest.

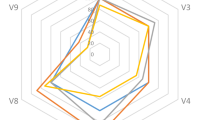

Enzyme activities

The soil enzyme activities varied across all sites and treatments (Fig. 3). The soil collection sites had a significant, independent effect on the nitrate reductase activity (Df = 4, F-value = 65.74, p < 0.001), acid phosphatase activity (Df = 4, F-value = 17.36, p < 0.001) and glucosidase activity (Df = 4, F = 8.01, p < 0.001). Additionally, the species used had a significant independent effect on the nitrate reductase activity (Df = 2, F-value = 53.45, p < 0.001), acid phosphatase activity (Df = 2, F-value = 97.82, p < 0.001) and glucosidase activity (Df = 2, F-value = 104.33, p < 0.001). There was a significant, interaction effect between the species used and the collection site on the nitrate reductase activity (Df = 8, F-value = 92.59, p < 0.001), acid phosphatase activity (Df = 8, F-value = 35.02, p < 0.001) and glucosidase activity (Df = 8, F-value = 15.81, p < 0.001) observed in the soils. Nitrate reductase activities increased significantly in Mvutshini post-V. sativa harvest, increased in Mzinto post-V. sativa and V. villosa harvest and decreased significantly in Hibberdene and Gingindlovu post-V. villosa harvests (Fig. 3A). Acid phosphatase activities increased significantly in Gingindlovu and Hibberdene post-V. villosa harvest, and also increased in Mvutshini soils post-V. sativa and V. villosa harvest (Fig. 3B). The glucosidase activities increased significantly across all sites and treatments (Fig. 3C).

The enzyme activities of soil collected from (A) Mvutshini, (B) Mpembeni, (C) Mzinto, (D) Hibberdene and (E) Gingindlovu pre-planting and post-Vicia sativa and Vicia villosa harvest. The different values are presented as mean ± SE. Different letters show significant differences between treatments after Two-Way ANOVA.

Plant biomass and mineral nutrition

Vicia sativa accumulated significantly higher total biomass and root biomass in Mzinto plantation soils (Table 2). Gingindlovu-grown V. villosa plants accumulated more biomass, with Gingindlovu showing a significantly higher root: shoot ratio (Table 2).

Vicia villosa grown in Hibberdene died before the final harvest date was reached.

Vicia sativa cultivated in Mzinto, Hibberdene, and Gingindlovu had the highest specific N absorption rates compared to Mvutshini and Mpembeni (Fig. 4A). Mzinto showed the highest N utilisation rate, followed by Gingindlovu, while Hibberdene showed a decrease in N utilisation (Fig. 4B). Mpembeni and Gingindlovu showed increased P absorption rates, while Hibberdene showed a decrease in P absorption rates (Fig. 4C). Hibberdene showed the highest P utilisation rate (Fig. 4D).

The (A) Specific N Absorption Rate, (B) Specific N Utilization Rate, (C) Specific P Absorption Rate and (D) Specific P Utilisation Rate of Vicia sativa plants grown in (A) Mvutshini, (B) Mpembeni, (C) Mzinto, (D) Hibberdene and (E) Gingindlovu plantation soil for 45 days. The different values are presented as mean ± SE. The different letters show significant differences between the treatments after One-Way ANOVA.

Vicia villosa grown in Mpembeni had the highest specific N assimilation rate, while Mzinto and Gingindlovu had the lowest (Fig. 5A). Gingindlovu had the highest specific N utilisation rate, while Mzinto had the lowest (Fig. 5B). The specific P assimilation rate was highest in Gingindlovu, while the other sites didn’t show significant differences (Fig. 5C). Lastly, the specific P utilisation rate was highest in Mpembeni and lowest in Mzinto (Fig. 5D).

The (A) Specific N Utilisation Rate, (B) Specific N Assimilation Rate, (C) Specific P Assimilation Rate and (D) Specific P Utilisation Rate of Vicia villosa plants grown in (A) Mvutshini, (B) Mpembeni, (C) Mzinto, (D) Hibberdene and (E) Gingindlovu plantation soil for 45 days. The different values are presented as mean ± SE. The different letters show significant differences between the treatments after One-Way ANOVA.

Mzinto had the highest %N derived from the atmosphere (55%), while Mpembeni had the lowest (20%) (Fig. 6A). Total plant N content was highest in Mzinto and lowest in Hibberdene (Fig. 6B). Plants from all the sites derived most of their N from the soil, except for Mzinto, which derived most of its N from the atmosphere (Fig. 6C). Total plant P content was the lowest in Hibberdene (Fig. 6D). Mzinto had the highest %NDFA (41%), while Gingindlovu had the lowest (5%) (Fig. 7A). Mpembeni-grown V. villosa had the highest plant N, followed by Gingindlovu (Fig. 7B). All the plants from the different plantation sites derived most of their N from the soil (Fig. 7C). Vicia villosa cultivated in Gingindlovu had the highest total P content, while Mzinto had the lowest (Fig. 7D).

The (A) % N derived from the atmosphere, (B) Total Plant N concentrations (C) Total N concentrations derived from the atmosphere vs. N derived from the soil and D. Total Plant P concentrations in Vicia sativa plants grown in (A) Mvutshini, (B) Mpembeni, (C) Mzinto, (D) Hibberdene and (E) Gingindlovu plantation soil for 45 days. The values are presented as mean ± SE. The different letters show significant differences after One-Way ANOVA.

The (A) %N derived from the atmosphere, (B) Total Plant N concentrations (C) N concentrations derived from the atmosphere vs. soil and (D) Total Plant P concentrations of Vicia villosa plants grown in (A) Mvutshini, (B) Mpembeni, (C) Mzinto, (D) Hibberdene and (E) Gingindlovu plantation soil for 45 days. The different values are presented as mean ± SE. The different letters show significant differences between the treatments after One-Way ANOVA.

Discussion

The study investigated the effects of planting V. sativa and V. villosa as cover crops in nutrient-deficient KZN small-scale sugarcane plantation soils. Post-harvest soil analysis showed a decrease in soil nitrogen (N) concentrations in Mvutshini, Mpembeni, Mzinto, Hibberdene and Gingindlovu under both V. sativa and V. villosa, suggesting that these legumes were highly effective in utilising available soil N for their growth. This is consistent with the known capacity of legumes to fix atmospheric N through their symbiotic relationship with rhizobia, which often leads to a reduction in soil N as the plant absorbs it for biomass production [18; 60]. However, the lack of significant differences in N concentrations in most sites indicates either a lower initial N content or varying soil properties that might influence N fixation and absorption differently. The significant decrease in soil phosphorus (P) concentrations in Mpembeni and Hibberdene under V. sativa treatment and in Gingindlovu under V. villosa legume treatments indicates that the plants were actively utilising P, which is crucial for their energy transfer and metabolic processes. These results align with the findings of Mao et al.22 and Park et al.39, who reported similar declines in soil P levels in the rhizosphere of legume species due to high uptake. Phosphorus is often a limiting nutrient in many soils, and its depletion post-harvest highlights the potential need for replenishment through fertilisation in subsequent growing cycles. Potassium (K) concentrations varied significantly across the sites, with a notable increase in Mvutshini and a decrease in Hibberdene under both species’ treatments. The increase in K concentration in Mvutshini may be attributed to the mineralisation of organic matter or the release of K from soil minerals, a process that can be enhanced in the presence of legumes due to their root exudates40, which alter soil chemistry. Conversely, the decrease in Hibberdene could be related to the specific soil characteristics of the site, which may limit K availability or result in its leaching post-harvest. The increase in calcium (Ca) concentrations regardless of the legume species, suggests that both V. sativa and V. villosa may contribute to the mobilisation and uptake of Ca from the soil. However, the lack of significant differences after a post-hoc analysis can be attributed to the reduced sensitivity of the non-parametric alternative used when analysing the results. Similar findings have been reported by Lu et al.41, who observed increased Ca mobilisation in the rhizosphere of Leymus chinensis, Bromus inermis, Stipa grandis, Koeleria cristata, Medicago sativa and Astragalus adsurgens compared to unplanted soils potentially due to root-mediated soil pH changes that improve Ca availability. The increase in magnesium (Mg) concentrations in Mvutshini and Mpembeni, though non-significant in Mzinto, Hibberdene, and Gingindlovu, further supports the idea that these legumes can enhance the availability of certain cations, which is crucial for plant development and enzyme function. Notably, while Mg is crucial for nodule formation and N fixation in legumes42, the increased Mg concentrations in this study did not result in nodulation. This highlights the direct effect and dependency of legumes on P for successful nodulation and N fixation.

The increase in soil pH across most sites indicates that the legumes may have ameliorated soil acidity through the release of basic root exudates or the accumulation of basic cations like Ca and Mg43. This observation is supported by previous studies, which have shown that leguminous plants can raise soil pH, making the soil environment more favourable for microbial activity and nutrient availability44,45. The varied responses might be due to site-specific soil properties that buffer against pH changes or a lower density of root activity. Soil acidity is a key constraint associated with poor root health and nutrient availability46. Under acidic conditions, nutrients such as P form insoluble complexes with cations, rendering them unavailable for plant uptake47. Since P is an important macronutrient required for metabolic processes in plants and is a significant constituent of ATP, its deficiency can decrease the photosynthetic rates43 and N fixation in legumes48. The decreased biomass and %NDFA across all plantation soil treatments in this study can be linked to V. sativa and V. villosa using the available P sparingly to maintain growth function. This is shown by the low P utilisation rates across all soil treatments. Legumes switch their N sources during nutritional stress, favouring soil N to reserve energy49. Biological N fixation (BNF) is a high-energy process and requires 16 ATP molecules to fix one molecule of atmospheric N2 to NH350. Vicia sativa and V. villosa growing in Mvutshini, Mpembeni, and Gingindlovu plantation soils showed a reduced %NDFA and increased their reliance on soil N. This shows that the plants were able to use the deficient soil P sparingly, reducing the ATP-demanding BNF to maintain their growth and function. These findings are similar to findings reported by Alkama et al.51, Benner and Vitousek52, and Miguez-Montero et al.53, who observed decreased N2 fixation rates under low P, which were reversed when P inputs were increased. Variations in the responses observed across different sites could be attributed to the agricultural practices and climatic conditions of the different collection sites. Soil management techniques such as tillage and fertilisation practices, as well as duration in the duration of sugarcane farming, can significantly impact soil structure, organic matter formation and nutrient cycling54. Interestingly, Hibberdene-grown V. villosa died before harvest, while V. sativa persisted. This could be attributed to the documented persistence of V. sativa in diverse environments where other legumes would be poorly suited55.

The substantial increase in bacterial strains post-harvest under both V. sativa and V. villosa across all sites highlights the beneficial impact of these legumes on soil microbial diversity. Both species increased the presence of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR), with N-fixing, N-cycling, and P-solubilising functions in the genus Arthrobacter, Bacillus, Burkholderia, Caulobacter and Pseudomonas. The observed increase indicates that these plants create a favourable environment for microbial proliferation, possibly through root exudates that serve as carbon sources for microbes25. The presence of these bacterial species post-harvest can be attributed to the release of different compounds, such as organic acids by the legumes, increasing bacterial activity during nutrient deficiency25. The composition and function of rhizospheric bacteria can be influenced by the composition and quantity of root exudates released by the plants25. During nutrient deficiency, plant roots can modulate the chemical composition of their exudates according to the plants’ requirements25. This influences the composition of the rhizospheric microbial community and forms the basis for the attraction and repulsion of certain bacterial species56,57,57. The experimental soils in this study were N and P deficient; this may have resulted in an increase in N-fixing and phosphate solubilising activities and efficiency to compensate for the soil-deficient nutrients for plant use. This suggests an increase in the root exudates signals of V. sativa and V. villosa roots for N and P-cycling bacteria under nutrient-deficient conditions25. Similar results were obtained by Mula-Michel et al.58 who reported increases in bacterial diversity under soybean soils compared to sugarcane monoculture. Gao et al.45 reported that cover crop treatments increased the relative abundance of Streptomyces, Arthrobacter and Bacillus sp. compared to no cover crop treatments. Therefore, it would be expected that in a sugarcane-V. sativa or V. villosa rotation system, nutrient cycling microbes and associated enzymes would increase activities, increasing nutrient fixing and cycling of deficient soil nutrients in sugarcane plantation soils. Bacteria from these genera have been reported to mineralise phosphates by secreting acid phosphatases and phytases59. The significant increase in acid phosphatase activities in Gingindlovu and Hibberdene post-V. villosa harvest, along with increased activities in Mvutshini soils post-V. sativa and V. villosa harvest, indicates that these plants enhance phosphorus cycling in the soil by promoting the microbial production of phosphatase enzymes. This could be attributed to the co-occurrence of Burkholderia and Pseudomonas in Mzinto and Pseudomonas, Bacillus and Burkholderia in Mvutshini. Mixed cultures of P-solubilising bacteria are more effective in mineralising organic phosphates60. Park et al.39 found that the co-inoculation of Burkholderia anthina and Enterobacter aerogenes released the highest soluble P content as compared to single inoculations. The presence of these P-solubilising bacteria makes available the cation bound P, increasing P availability for plant assimilation, and this is shown by the increased P assimilation rates in this study across all sites61,62. The consistent increase in glucosidase activities across all sites and treatments further supports the idea that these legumes enhance soil health by promoting microbial activity. Glucosidases are involved in the breakdown of carbohydrates, releasing simple sugars that can be utilized by both plants and microbes63, thus maintaining a dynamic and resilient soil ecosystem. These enzymes are crucial for breaking down organic phosphorus compounds into inorganic forms that plants can absorb, and their elevated activity suggests a healthy phosphorus cycle in the rhizosphere.

The significant increase in nitrate reductase activity in Mvutshini post-V. sativa harvest and in Mzinto under both legume treatments suggests that these soils have an active N cycle, with microbes efficiently converting nitrate into forms available for plant uptake. This is coherent with the observed increased %NDFA values in Mzinto-grown plants, and at the time, the soil had high P concentrations and decreased acidity. Even though the plants in this study did not nodulate, the plants were able to reduce atmospheric N, suggesting a symbiosis with non-nodulating endophytic N2 fixing rhizobacteria49. Similar results were recorded by49, who reported high %NDFA in non-nodulated Leucaena leucocephala plants growing in grassland ecosystem soils. The high V. sativa N concentrations, despite low soil N concentrations in Mzinto plantation soils, can indicate the high efficiency of the free-living N-fixing bacteria and P-solubilising bacteria isolated from the rhizosphere of these plantation soils. This is further supported by the increased nitrate reductase and acid phosphatase activities in Mzinto plantation soils post-V. sativa harvest. Soil N and P concentrations decreased post-harvest, possibly due to the uptake and use of nutrients by the legumes during growth64. These results are consistent with those observed by Zhou et al.65 and Weerasekara et al.64, who reported decreases in soil nutrient contents under cover crop treatments. However, the scavenged nutrients can be made available for the subsequent crop through the decomposition and mineralisation of V. sativa and V. villosa when it is incorporated into the soil as legume biomass66. In a study by Perrone et al.18, vetch ecotypes contributed up to 211 kg N ha− 1 from aboveground biomass. This serves as a sustainable form of N and P feedback as the nutrients released from the slow decomposition of the legume biomass reduce contaminant leaching from the application of chemical fertilisers67, and provide a steady amount of N throughout the growing season68. Furthermore, the organic matter present from the rotation and buried legume biomass may be resistant to biological degradation, fostering a longer and deeper carbon stock in the soil. This extended carbon stock is beneficial to the subsequent plant28. Soil rehabilitation processes occur over an extended period. Therefore, field trials over a prolonged experimental duration might elicit different responses as plant-microbe interactions are sensitive to environmental conditions, which might affect their associated enzyme activities and nutritional contributions. Given the effects of climatic variability on soil chemistry and plant-microbe interactions, future studies should include field trials across various locations and climatic gradients, as this could provide more insight into the effectiveness of these species across diverse environmental and soil conditions. Identifying and quantifying the root exudates released by V. sativa and V. villosa would help better understand the interactions between plant roots and soil ecosystems. Additionally, future studies should use next-generation sequencing to identify all the microbial populations present, which will better estimate the microbial diversity and the effects that the legume species had on the soil microbiota.

Conclusion

In this study, V. sativa and V. villosa increased the bacterial composition, acid phosphatase, and glucosidase activities and reduced the exchange acidity in the sugarcane plantation soils, and these are an indicator of improved soil health as proposed in our hypotheses. However, the responses varied across sites, reflecting the influence of local soil conditions on the effectiveness of these legumes. While these species showed potential for improving soil health, their contribution to soil fertility remains limited when used as cover crops alone. Prolonged planting durations and incorporating the plant biomass into the soil could further enhance their benefits by increasing root exudation, bacterial composition, and activity, thereby promoting nutrient cycling. Incorporating the plant biomass would also return assimilated nutrients to the soil in bioavailable forms, contributing to improved soil fertility over time. Therefore, integrating V. sativa and V. villosa into crop rotations or as cover crops in sugarcane fields is a promising strategy for enhancing soil biological health. However, to fully realise their potential in improving fertility, planting them should be combined with biomass incorporation. This combined approach could reduce dependency on chemical fertilisers, promote nutrient cycling, restore soil health, and support sustainable agricultural practices in sugarcane plantations.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study will be stored and available in ResearchGate corresponding author (Anathi Magadlela) account and tagged to the manuscript: Vicia sativa and Vicia villosa enhance soil microbial composition, enzyme activities, and chemical properties in nutrient-deficient small-scale sugarcane plantation soils. Also, all raw data can be requested from the corresponding author, Prof. Anathi Magadlela at anathimagadlela@icloud.com.

References

Benke, K. & Tomkins, B. Future food-production systems: Vertical farming and controlled-environment agriculture. Sustainability: Sci. Pract. Policy. 13 (1), 13–26 (2017).

FAO. Database on Arable land 2016 [Available from: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/AG.LND.ARBL.HA.PC?end¼2013&start¼1961&view¼chart

Gerland, P. et al. World population stabilization unlikely this century. Science 346 (6206), 234–237 (2014).

Chun, I-A., Ryu, S-Y., Park, J., Ro, H-K. & Han, M-A. Associations between food insecurity and healthy behaviors among Korean adults. Nutr. Res. Pract. 9 (4), 425 (2015).

Hendriks, S. South Africa’s national development plan and new growth path: Reflections on policy contradictions and implications for food security. Agrekon 52 (3), 1–17 (2013).

Bayat, A., Louw, W. & Rena, R. The impact of socio-economic factors on the performance of selected high school learners in the Western Cape Province, South Africa. J. Hum. Ecol. 45 (3), 183–196 (2014).

STATSSA. Focus on food inadequacy and hunger in South Africa in 2021 2021 [Available from: https://www.statssa.gov.za/?p=16235#:~:text=Results%20indicate%20that%20out%20of,inadequate%20access%20to%20food%2C%20respectively

Siphesihle, Q. & Lelethu, M. Factors affecting subsistence farming in rural areas of Nyandeni local municipality in the Eastern Cape Province. South. Afr. J. Agricultural Ext. 48 (2), 92–105 (2020).

Zantsi, S. & Bester, B. Revisiting the benefits of animal traction to subsistence smallholder farmers: a case study of ndabakazi villages in Butterworth, Eastern Cape Province of South Africa. South. Afr. J. Agricultural Ext. 47 (3), 1–13 (2019).

Mthembu, B. E., Everson, T. M. & Everson, C. S. Intercropping for enhancement and provisioning of ecosystem services in smallholder, rural farming systems in KwaZulu-Natal Province, South Africa: a review. J. Crop Improv. 33 (2), 145–176 (2019).

Hlatshwayo, S. I. et al. The determinants of crop productivity and its effect on food and nutrition security in rural communities of South Africa. Front. Sustainable food Syst. 7, 1091333 (2023).

Zulu, N. S., Sibanda, M. & Tlali, B. S. Factors affecting sugarcane production by small-scale growers in Ndwedwe Local Unicipality, South Africa. Agriculture 9 (8), 170 (2019).

Belete, T. & Yadete, E. Effect of mono cropping on soil health and fertility management for sustainable agriculture practices: A review. J. Plant. Sci. 11 (6), 192–197 (2023).

Graham, M., Haynes, R. & Meyer, J. Changes in soil chemistry and aggregate stability induced by fertilizer applications, burning and trash retention on a long-term sugarcane experiment in South Africa. Eur. J. Soil. Sci. 53 (4), 589–598 (2002).

Adesemoye, A. O. & Kloepper, J. W. Plant–microbes interactions in enhanced fertilizer-use efficiency. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 85 (1), 1–12 (2009).

Rosenstock, T. S. et al. Agroforestry with N2-fixing trees: Sustainable development’s friend or foe? Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 6, 15–21 (2014).

Abd-Alla, M. H., Issa, A. A. & Ohyama, T. Impact of harsh environmental conditions on nodule formation and dinitrogen fixation of legumes. Adv. Biology Ecol. Nitrogen Fixation. 9, 1 (2014).

Perrone, S., Grossman, J., Liebman, A., Sooksa-Nguan, T. & Gutknecht, J. Nitrogen fixation and productivity of winter annual legume cover crops in upper midwest organic cropping systems. Nutr. Cycl. Agrosyst. 117, 61–76 (2020).

Sun, W. H., Wu, F. F., Cong, L., Jin, M. Y. & Wang, X. G. Assessment of genetic diversity and population structure of the genus Vicia (Vicia L.) using simple sequence repeat markers. Grassl. Sci. 68 (3), 205–213 (2022).

Carreón-Abud, Y. & Sanchez-Yañez, J. Rhizosphere effect of Vicia sativa L. on soil microbial population from Tiripetio town, Michoacan, México. Biologicas 4 (1998).

Ibañez, S., Medina, M. I. & Agostini, E. Vacia: A green bridge to clean up polluted environments. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 104 (1), 13–21 (2020).

Mao, L., Zhu, R., Yi, K., Wang, X. & Sun, J. Transcriptome Analysis of Vicia villosa in response to low phosphorus stress at seedling stage. Agronomy 13 (7), 1665 (2023).

Abawi, G. & Widmer, T. Impact of soil health management practices on soilborne pathogens, nematodes and root diseases of vegetable crops. Appl. Soil. Ecol. 15 (1), 37–47 (2000).

Marais, A., Hardy, M., Booyse, M. & Botha, A. Effects of monoculture, crop rotation, and soil moisture content on selected soil physicochemical and microbial parameters in wheat fields. Appl. Environ. Soil Sci. (2012).

Yetgin, A. The dynamic interplay of root exudates and rhizosphere microbiome. Soil. Stud. 12 (2), 111–120 (2023).

Génard, T., Etienne, Laîné, P., Yvin, J-C. & Diquélou, S. Nitrogen transfer from Lupinus albus L., Trifolium incarnatum L. and Vicia sativa L. contribute differently to rapeseed (Brassica napus L.) nitrogen nutrition. Heliyon 2 (9), e00150 (2016).

Jani, A. D., Grossman, J., Smyth, T. J. & Hu, S. Winter legume cover-crop root decomposition and N release dynamics under disking and roller-crimping termination approaches. Renewable Agric. Food Syst. 31 (3), 214–229 (2016).

Gregorich, E., Drury, C. & Baldock, J. Changes in soil carbon under long-term maize in monoculture and legume-based rotation. Can. J. Soil Sci. 81 (1), 21–31 (2001).

Ranells, N. N. & Wagger, M. G. Nitrogen release from grass and legume cover crop monocultures and bicultures. Agron. J. 88 (5), 777–882 (1996).

Yang, C. et al. Seed-germination ecology of Vicia villosa Roth, a cover crop in orchards. Agronomy 12 (10), 2488 (2022).

Thibane, Z., Soni, S., Phali, L. & Mdoda, L. Factors impacting sugarcane production by small-scale farmers in KwaZulu-Natal Province-South Africa. Heliyon 9, e13061 (2023).

Ndlovu, M. et al. An Assessment of the impacts of climate variability and change in KwaZulu-Natal Province, South Africa. Atmosphere 12 (2021).

Jackson, C. R., Tyler, H. L. & Millar, J. J. Determination of microbial extracellular enzyme activity in waters, soils, and sediments using high throughput microplate assays. JoVE (J. Vis. Exp.) (80), e50399. (2013).

Bruckner, A., Wright, J., Kampichler, C., Bauer, R. & Kandeler, E. A method of preparing mesocosms for assessing complex biotic processes in soils. Biol. Fertil. Soils. 19, 257–262 (1995).

Farquhar, G. D., Ehleringer, J. R. & Hubick, K. T. Carbon isotope discrimination and photosynthesis. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 40 (1), 503–537 (1989).

Shearer, G. & Kohl, D. H. N2-fixation in field settings: Estimations based on natural 15 N abundance. Funct. Plant Biol. 13 (6), 699–756 (1986).

Nielsen, K. L., Eshel, A. & Lynch, J. P. The effect of phosphorus availability on the carbon economy of contrasting common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) genotypes. J. Exp. Bot. 52 (355), 329–339 (2001).

Ågren, G. I. & Franklin, O. Root: shoot ratios, optimization and nitrogen productivity. Ann. Botany. 92 (6), 795–800 (2003).

Park, J-H., Lee, H-H., Han, C-H., Yoo, J-A. & Yoon, M-H. Synergistic effect of co-inoculation with phosphate-solubilizing bacteria. Korean J. Agricultural Sci. 43 (3), 401–414 (2016).

Yang, Y., Yang, Z., Yu, S. & Chen, H. Organic acids exuded from roots increase the available potassium content in the Rhizosphere Soil: A Rhizobag experiment in Nicotiana tabacum. HortScience 54, 23–27 (2019).

Lu, J. et al. Rhizosphere priming and effects on mobilization and immobilization of multiple soil nutrients. Soil Biol. Biochem. 199, 109615 (2024).

Khaitov, B. Effects of Rhizobium inoculation and magnesium application on growth and nodulation of soybean (Glycine max L.). J. Plant Nutr. 41 (16), 2057–2068 (2018).

Xu, H., Weng, X. & Yang, Y. Effect of phosphorus deficiency on the photosynthetic characteristics of rice plants. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 54, 741–748 (2007).

Balota, E. L. & Chaves, J. C. D. Microbial activity in soil cultivated with different summer legumes in coffee crop. Brazilian Archives Biology Technol. 54, 35–44 (2011).

Gao, H., Tian, G., Khashi u Rahman, M. & Wu, F. Cover crop species composition alters the soil bacterial community in a continuous pepper cropping system. Front. Microbiol. 12, 789034 (2022).

van Antwerpen, R., Titshall, L., McFarlane, S. & Keeping, M. (eds) Soil regenerative agriculture in the South African sugarcane industry. Proceedings of the international society of sugar cane technologists (2023).

Vance, C. P., Graham, P. H. & Allan, D. L. Biological nitrogen fixation: phosphorus-a critical future need? Nitrogen fixation: From molecules to crop productivity. 509–4 (2000).

Høgh-Jensen, H., Schjoerring, J. K. & Soussana, J. F. The influence of phosphorus deficiency on growth and nitrogen fixation of white clover plants. Ann. Botany. 90 (6), 745–753 (2002).

Sithole, N., Tsvuura, Z., Kirkman, K. & Magadlela, A. Nitrogen source preference and growth carbon costs of Leucaena leucocephala (Lam.) De Wit saplings in South African grassland soils. Plants 10 (11), 2242 (2021).

Vance, C. P., Uhde-Stone, C. & Allan, D. L. Phosphorus acquisition and use: Critical adaptations by plants for securing a nonrenewable resource. New Phytol. 157 (3), 423–447 (2003).

Alkama, N., Ounane, G. & Drevon, J. J. Is genotypic variation of H + efflux under P deficiency linked with nodulated-root respiration of N2–Fixing common-bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L)? J. Plant Physiol. 169 (11), 1084–1089 (2012).

Benner, J. W. & Vitousek, P. M. Cyanolichens: A link between the phosphorus and nitrogen cycles in a hawaiian montane forest. J. Trop. Ecol. 28 (1), 73–81 (2012).

Míguez-Montero, M., Valentine, A. & Pérez-Fernández, M. Regulatory effect of phosphorus and nitrogen on nodulation and plant performance of leguminous shrubs. AoB Plants. 12 (1), plz047 (2020).

Samson, M-E. et al. Crop response to soil management practices is driven by interactions among practices, crop species and soil type. Field Crops Res. 243, 107623 (2019).

Huang, Y., Gao, X., Nan, Z. & Zhang, Z. Potential value of the common vetch (Vicia sativa L.) as an animal feedstuff: A review. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 101 (5), 807–823 (2017).

Chaparro, J. M., Sheflin, A. M., Manter, D. K. & Vivanco, J. M. Manipulating the soil microbiome to increase soil health and plant fertility. Biol. Fertil. Soils. 48, 489–499 (2012).

Kumar, R. et al. Establishment of Azotobacter on plant roots: Chemotactic response, development and analysis of root exudates of cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) and wheat (Triticum aestivum L). J. Basic Microbiol. 47 (5), 436–439 (2007).

Mula-Michel, H., White, P. & Hale, A. Immediate impacts of soybean cover crop on bacterial community composition and diversity in soil under long-term Saccharum monoculture. PeerJ 11, e15754 (2023).

Jorquera, M. A., Hernández, M. T., Rengel, Z., Marschner, P. & de la Luz Mora, M. Isolation of culturable phosphobacteria with both phytate-mineralization and phosphate-solubilization activity from the rhizosphere of plants grown in a volcanic soil. Biol. Fertil. Soils. 44, 1025–1034 (2008).

Molla, M., Chowdhury, A., Islam, A. & Hoque, S. Microbial mineralization of organic phosphate in soil. Plant. soil. 78, 393–399 (1984).

Katsalirou, E., Deng, S., Gerakis, A. & Nofziger, D. L. Long-term management effects on soil P, microbial biomass P, and phosphatase activities in prairie soils. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 76, 61–69 (2016).

Wang, Y. et al. Long-term cover crops improved soil phosphorus availability in a rain-fed apple orchard. Chemosphere 275, 130093 (2021).

Stott, D., Andrews, S. S., Liebig, M. A., Wienhold, B. & Karlen, D. Evaluation of β-Glucosidase activity as a soil quality indicator for the soil management assessment framework. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 74, 107–119 (2010).

Weerasekara, C. S. et al. Effects of cover crops on soil quality: Selected chemical and biological parameters. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 48 (17), 2074–2082 (2017).

Zhou, X. et al. Symbiotic nitrogen fixation and soil N availability under legume crops in an arid environment. J. Soils Sediments. 11, 762–770 (2011).

Shennan, C. Cover crops, nitrogen cycling, and soil properties in semi-irrigated vegetable production systems. HortScience 27 (7), 749–754 (1992).

Salmerón, M., Isla, R. & Cavero, J. Effect of winter cover crop species and planting methods on maize yield and N availability under irrigated Mediterranean conditions. Field Crops Res. 123 (2), 89–99 (2011).

Dinnes, D. L. et al. Nitrogen management strategies to reduce nitrate leaching in tile-drained midwestern soils. Agron. J. 94 (1), 153–171 (2002).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the support of the University of KwaZulu-Natal, School of Life Sciences, Durban, South Africa.

Funding

The research leading to the results received funding from the National Research Foundation under Grant agreement number (Grant UID 138091).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualisation, A. M; methodology, A. M and E. N; validation, A. M, M.P, and E. N; formal analysis, E. N; writing-original draft preparation, E. N; writing-review and editing, A. M and M. P.; supervision, A. M; project administration, A. M and E. N; funding acquisition, A. M. All authors reviewed the manuscript before submission for publication. Corresponding author M.P.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ngonini, E., Pérez-Fernández, M.A. & Magadlela, A. Varying effects of Vicia sativa and Vicia villosa on bacterial composition and enzyme activities in nutrient-deficient sugarcane soils under greenhouse conditions. Sci Rep 15, 3317 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87910-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87910-y