Abstract

Although hemoplasma infection has been widely described in animals, a few studies have been conducted involving human populations, mostly as case reports. This was a cross-sectional epidemiological study that accessed hemoplasma infection in individuals and dogs from ten Indigenous communities of southern and southeastern Brazil. A total of 23/644 (3.6%) individuals of ten Indigenous communities tested positive to hemoplasmas by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) (cycle threshold; Ct ≤ 34.4), with 3/644 (0.5%) Mycoplasma haemocanis detection. In addition, 91/416 (21.9%) dogs were positive to hemoplasmas by qPCR, with 54/91 (59.3%) for M. haemocanis, 27/91 (29.7%) for Candidatus Mycoplasma haematoparvum, and 10/91 (11.0%) for both. Molecular diagnosis of M. haemocanis in Indigenous people herein may be consequence of daily close contact with dogs and different potential vectors. Although apparently healthy individuals, hemoplasma infection should be considered as differential diagnosis in likely overexposed populations, such as Indigenous individuals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hemotropic mycoplasmas (hemoplasmas) are small, pleomorphic, uncultivable bacteria which attacks erythrocytes cells of mammalian species, including rare human cases1,2, causing from asymptomatic disease to acute hemolytic anemia and pyrexia3.

As suggested by a previous study, Indigenous territories and populations have been historically overlapped with vector-borne diseases occurrence worldwide4, associated with lowest government investment in health per country and low income in these tropical and subtropical areas4.

Although hemoplasma infection has been widely described in animals, few studies have been conducted involving human populations, mostly as case reports. Due to their contact with animals and vectors, Indigenous populations worldwide may be exposed to hemoplasma infection, with no study to date.

Results

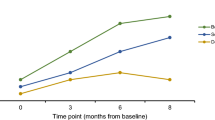

A total of 23/644 (3.6%) Indigenous individuals were molecularly positive for hemoplasma infection by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) (cycle threshold- Ct ≤ 34.4; standard deviation of 5,18; minimum value:12,139; maximum value 33,847), with 20/23 (87.0%) positive samples from the Kopenoty community (20/125; 16.0%), São Paulo State, southeastern Brazil. The other three positive human samples were from 2/181 (1.1%) persons in Ocoy and 1/29 (3.4%) in Tupã Nhe’é Kretã Indigenous communities, Paraná State, southern Brazil (Table 1; Fig. 1). As previously reported, nonspecific amplicons have been commonly observed in the no-template controls rather than in uninfected samples, with CT values ranging from 34.4 to 39.9, corresponding to < 10 copies/PCR5. Overall, 5/23 (21.7%) positive individuals presented anemia (< 40% for men, and < 35% for women), including 5/20 (25.0%) positive individuals from Kopenoty (19/125;15.2% presented anemia), 0/2 from Ocoy (0/181 presented anemia) and 0/29 from Tupã Nhe’é Kretã community (4/29; 13.8% presented anemia). Tick bite history was referred by 163/472 (34.5%) Indigenous people herein. Due to the low human Mycoplasma spp. positivity herein, associated risk factors could not be assessed and tested.

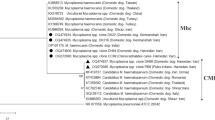

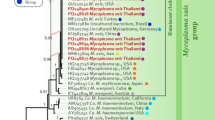

The results of 16 S ribosomal RNA gene sequencing confirmed Mycoplasma heamocanis infection in one human sample of Ocoy community, Paraná state, southern Brazil. In addition, two human samples of Kopenoty community and the same Ocoy sample also confirmed Mycoplasma haemocanis by targeted next-generation sequencing (tNGS) and phylogenetic analysis (Fig. 1). The resulting 16s amplicon sequences and RNase P amplicon sequences obtained from the three positive human samples were deposited in the GenBank® nucleotide database under the accession numbers PQ240646, PQ240647, PQ246155, PQ246156, and PQ246157.

A total of 91/416 (21.9%) dogs were positive to hemoplasmas by qPCR, 54/91 (59.3%) for M. haemocanis, 27/91 (29.7%) for Candidatus Mycoplasma haematoparvum, and 10/91 (11.0%) for both (Fig. 2).

Phylogenetic analysis of amplicon sequences obtained by tNGS Neighbor-Joining trees of 16 S rRNA gene sequences from one positive human sample (Ocoy 136, Fig. 2 panels A and B) and an UPGMA tree of RNase P gene sequences from three positive human samples (Ocoy 136, KOP-02, KOP-08, Fig. 2 panel C) showed the sequences grouped with Mycoplasma haemocanis. Portions of the 16 S rRNA gene sequence were identical between M. haemocanis and M. haemofelis (Fig. 2 panel B); thus, use of the RNase P gene was better to distinguish between these two species (Fig. 2 panel C).

Although a total 416 dogs living in the Indigenous communities were sampled and tested for Hemoplasma infection, information was reliable only for 395/416 (95.0%) dogs, which were accessed and gathered to evaluate the associated risk factors with Mycoplasma infection, with statistical outcome summarized and presented (Table 2). Despite a statistical significance was observed when comparing the prevalences for Mycoplasma species (McNemar’s Chi-squared test: 8.35, p: 0.004), no variable was associated with Mycoplasma haemocanis infection. Considering the Candidatus M. haematoparvum, the logistic regression revealed that dogs living in São Paulo State were less likely infected (OR: 0.26, p: 0.007), while the odds of infection were significantly increased for male dogs (OR: 4.28, p: 0.006). Although a statistically significant association was also observed between Candidatus M. haematoparvum infection and age of dogs by the Univariate analysis (p: 0.025), such variable was not retained by the final logistic regression. In addition, 112/395 (28.3%) dogs sampled herein have presented tick infestation during samplings, including 22/112 (19.6%) positive to Mycoplasma spp. No statistical association was observed between tick infestation and Mycoplasma spp. positivity (95% CI: 0.7947–4.007; p: 0.224).

Discussion

This is a cross-sectional epidemiological approach detecting hemoplasma infection in owners and their dogs. This study has detected hemoplasma in Indigenous populations, likely overexposed individuals to vector-borne pathogens, and presumptively, M. haemocanis detection in human individuals worldwide.

Human detection of hemoplasmas has been mostly reported in individuals with close contact with animals, including immunocompromised patients, veterinarians, researchers, farmers, travelers2,3,6,7,8,9. Molecular studies in human samples have previously detected Mycoplasma haemofelis, Mycoplasma suis, Candidatus Mycoplasma haemohominis, Mycoplasma ovis, and Mycoplasma haematoparvum (2,3,9–12). Clinical signs have varied from classical presentation of pyrexia, anemia, lymph adenomegaly, neutropenia, acute hemolysis to hepatosplenomegaly and neurological symptoms2,3,6,7,8,9. Herein, anemia was found in less than a quarter of positive human samples, which may have indicated mild or chronic infection by M. haemocanis, as observed in dogs10,11. Future studies should be conducted to fully establish the clinical presentation of M. haemocanis in Indigenous communities.

Mycoplasma haemocanis was the only Mycoplasma sp. detected in Indigenous communities herein, which was also the mostly detected hemoplasma species in dogs (54/91; 59.3%). Not surprisingly, Indigenous populations in Brazil have been exposed to other arthropod vectors, and close contact with domestic dogs as vector-borne pathogens reservoirs4. Despite the human M. haemocanis infection observed herein may be a consequence of daily close dog contact and multiple vectors, further studies should compare human-dog hemoplasma strains and pinpoint the role of dogs in human infection.

Mycoplasma haemocanis and Candidatus M. haematoparvum have been the major hemoplasma species infecting dogs worldwide10,11. However, no statistical difference of hemoplasma prevalence was observed between healthy and sick dogs infected by M. haemocanis and for Candidatus M. haematoparvum in the USA10. Such findings corroborated with the healthy aspect of positive dogs herein, considered as an enzootic dog stability against hemoplasmas11, which may contribute to underdiagnosis and spillover to human populations in vulnerable conditions, such as Indigenous communities. Additionally, cat-vector-human transmission should also be considered due to the similarity between M. haemocanis and Mycoplasma haemofelis genomes12, as observed in immunocompromised patients2. However, it is less likely to occur due to the higher prevalence of dogs and lower prevalence of cats in these communities.

The two main molecular challenges herein were to accurately confirm the human infection and pinpoint the Mycoplasma species involved. Our first report of human infection by Mycoplasma was in 2008 13, a single HIV positive patient co-infected by Mycoplasma haemofelis living in close contact with his five (two infected) cats. Since that, in a series of surveys, including wild boar hunters13, only one individual from a rural Brazilian settlement’s population was molecularly positive to Mycoplasma spp. by qPCR SYBR green, with no successful amplification of 16 S rRNA or 23 S rRNA genes despite multiple attempts14. Recently, the research group started surveying vulnerable populations highly exposed to ectoparasites and in continuous close contact with their companion animals. In all cases, to ensure true results, molecular detection was performed in different laboratories, with different protocols and methods.

In the present study, results were ensured by three careful steps. First, although concomitantly collected by nurses and veterinarians, human samples were processed, aliquoted and stored separately from dog samples, mostly due to biosafety regulations. Second, human blood DNA samples were extracted at the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (Fiocruz), Brazil and tested at the Clinical and Molecular Pathology Laboratory (CMPL) and the Animal Disease Diagnostic Laboratory (ADDL) in West Lafayette, IN, USA, while dog samples were sent from Brazil as whole blood in dry ice for DNA extraction and molecular testing at the Idexx Laboratories, Sacramento, CA, USA. Third, each laboratory performed a different molecular approach method for detection and Mycoplasma species identification: qPCR at the CMPL and Wideseq sequencing at Purdue, tNGS at the ADDL, and vector-borne qPCR diagnostic panel at the Idexx Laboratories. Thus, if not eliminated, human-dog sampling cross-contamination would be very unlikely.

In addition, molecular detection leading to Mycoplasma haemocanis identification in human samples was obtained by qPCR at CMPL and 16 S rRNA sequencing of resulted amplicons, independently confirmed by tNGS at the Animal Disease Diagnostic Laboratory (ADDL). As previously reported, mostly due to unsuccessful amplification14, only four out of 23 qPCR positive human samples resulted in useful sequencing. Molecular detection leading to Mycoplasma haemocanis and Mycoplasma haematoparvum identification in dogs was obtained by specific qPCR panel at the Idexx Laboratories.

In the present study, being a male dog was statistically associated with hemoplasma positivity, which was previously associated with Hemoplasma infection in rural and urban dogs of Chile 16 17, and in anemic dogs attended by a veterinary teaching hospital in Nigeria17. In addition to bloodsucking arthropods, alternative routes for hemoplasma transmission have been investigated and include direct contact during animal biting and fighting18. Thus, higher positivity to hemoplasmas in male dogs herein may be related to gender behavior due to aggressive territorial interactions and blood contact17. Despite previous studies have indicated tick bites as possible transmission route 2021, no statistical association was observed between tick infestation and Mycoplasma spp. positivity.

The hemoplasma positivity herein was statistically higher in dogs living in Paraná State, when compared to São Paulo State. In a previous study in the same Indigenous communities, dogs from the Paraná State were also 4-fold more likely seropositive to Toxoplasma gondii than São Paulo State, and highly associated with seropositive owners21. This higher exposure to neglected diseases was also observed in Indigenous communities of Parana state, including for Toxocara spp22. , Coxiella burnetti23 and Strongyloides stercoralis24, when compared to São Paulo State.

As limitations, no serological assay is currently available for hemoplasma diagnosis. Thus, human and animal hemoplasma detection has been solely relied on molecular detection, as presented herein. As another limitations herein, due to timeframe between collection and processing, PCV was not performed in all sampled dogs. In addition, as the study was designed for blood samples only, ticks and fleas were not collected from human and dogs during incursions. Due to very low hemoplasma positivity herein, tick bite history in Indigenous people could not be tested as associated risk factor. Although the vector competence of hemoplasmas transmission by tick and flea species remains unclear, future studies should also include ectoparasite sampling and molecular detection on these potential vectors.

Molecular diagnosis of M. haemocanis in Indigenous communities herein may be consequence of daily close contact with dogs and different potential vectors. Although apparently healthy individuals, hemoplasma infection should be considered as differential diagnosis in likely overexposed populations, such as Indigenous individuals. Likewise, the apparent healthy aspect of positive dogs herein may be consequence of enzootic dog stability against hemoplasmas, which may contribute to underdiagnosis and spillover to human populations in vulnerable conditions, such as Indigenous communities.

As Brazil currently presents 1.7 million of Indigenous individuals (0.83% of Brazilian population), distributed in 266 different ethnic communities, mostly located (87.5%) within the Amazon biome of the northern, central-western and northeastern regions, further studies with larger Indigenous samples, from different ethnicities and more clinically detailed data should be conducted, including molecular survey of other vector-borne confounding coinfections, to fully establish the relevant impact of Mycoplasma spp. infection in Indigenous communities.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional epidemiological study that accessed ten Indigenous communities of Guarani, Terena and Kaingang ethnicities in southern and southeastern Brazil, conducted from December 2020 through February 2022. Blood samples were collected via humans and dogs from cephalic (by credited nurses) and jugular (by credited veterinarians) venipuncture, respectively, after signed consent.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee in Human Health of the Brazilian Ministry of Health (protocol 52,039,021.9.0000.0102) and Ethics Committee of Animal Use (protocol number 033/2021) of the Federal University of Paraná. Before participating in the present study, informed consent was obtained from all human participants and/or their legal guardians. Before participating in the present study, each dog owner gave informed written consent for the study results to be used. All the procedures were designed to reduce animal suffering, and all owners were informed about the possible risks during blood samplings. All procedures were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations and complied with national and Brazilian legislation. Reporting of results follows the recommendations of the ARRIVE guidelines.

As no expected prevalence of Mycoplasma spp. infection has been available, the minimum sample size was determined with the confidence level of 95%, sampling error around the estimated proportion of 10% for an infinite population (> 25,000 indigenous people), concluding that a minimum of 400 individuals randomly selected.

Epidemiological questionnaire for Indigenous individuals has assessed age, gender, education level, Indigenous community and duration of residence, ethnicity, occupation, habit and frequency of hunting and animal owner status. Also, dog information about age, sex, breed, origin, community, access to forest, habit of hunting, presence of ectoparasites and vaccinations status was also accessed.

DNA was extracted from blood using the commercial kit, DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). Human samples were screened and tested in triplicate by a universal hemoplasma qPCR assay to detect hemoplasma 16 S rDNA gene (~ 200 bp) (SYBR™ Green PCR Master Mix, Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA USA), as previously described5. Two samples of naturally infected dogs with Mycoplasma haemocanis and two samples of swine with Mycoplasma suis were used as positive controls and ultrapure water was used as negative control. Positive samples were retested in triplicates and considered positive when the Ct (cycle threshold) was ≤ 34.4 26. The qPCR positive samples were submitted to conventional PCR for the nearly entire 16 S rRNA gene using a commercial PCR mix (GoTaq Colorless Master Mix, Promega Corporation, Madison, WI, USA). Amplicons with the expected DNA band size of around 1,500 bp were purified using a PCR Purification Kit (QIAquick, QIAGEN). All human positive samples were sequenced using the WideSeq method at the Purdue University Genomics Core Facility25. To ensure accurate results, samples were also submitted to Targeted Next Generation Sequencing (tNGS) at the Animal Disease Diagnostic Laboratory (ADDL)26, the official diagnostic laboratory for the State of Indiana, USA. Phylogenetic trees were generated using sequenced amplicons obtained by the tNGS assay. Sequences for hemotrophic mycoplasma species were obtained from GenBank and aligned with sequences obtained herein using Clustal Omega (1.2.2 in Geneious Prime- geneious.com). GenBank accession numbers were provided in the trees. Neighbor-Joining trees for two areas of the 16 S rRNA gene sequences (from sample Ocoy 136) were produced with Geneious Tree Builder using the Tamura-Nei distance model and bootstrapping with 1000 replicates (Geneious Prime). Mycoplasma pneumoniae was used as an outgroup. An UPGMA tree using the Tamura-Nei distance model was prepared with RNase P sequences (from samples Ocoy 136, KOP-02, and KOP-08) and 1000 bootstrap replicates (Geneious Prime). Bootstrap values > 70 were considered significant. Additionally, the packed cell volume (PCV) was measured in all blood samples obtained from human subjects. Canine blood samples were submitted for testing using the Canine Hemotropic mycoplasma RealPCR Test. (Idexx Reference Laboratory, Sacramento, CA, USA) for detection of Mycoplasma haemocanis and Candidatus Mycoplasma haematoparvum, as previously described27.

The gathered information was initially inserted into a spreadsheet and categorized. Comparison between positivity for M. haemocanis and Candidatus Mycoplasma haematoparvum in dogs living in the indigenous communities was assessed by McNemar chi-square test with continuity correction. The Chi-square test or Fisher´s exact test (univariate analysis) was applied to evaluate the association between positivity for the two Mycoplasma species. Variables with statistical significance (< 0.20) were exported to a multiple logistic regression model to determine the adjusted effects of the independent on the dependent variable. The multivariate model coefficients were assessed to estimate Odds Ratio values with respective 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). All analyses were conducted using the R software version 4.4.030, considering a 5% significance level.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are available in the GenBank® nucleotide database repository under the following accession numbers PQ240646, PQ240647, PQ246155, PQ246156, and PQ246157.

References

Biondo, A. W. et al. A review of the occurrence of hemoplasmas (hemotrophic mycoplasmas) in Brazil. Revista Brasileira De Parasitol. Veterinária 18, 1–7 (2009).

dos Santos, A. P. et al. Hemoplasma infection in HIV-positive patient, Brazil. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 14, 1922–1924 (2008).

Hattori, N. et al. Candidatus Mycoplasma Haemohominis in Human, Japan. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 26, 11–19 (2020).

Kmetiuk, L. B., Tirado, T. C., Biondo, L. M., Biondo, A. W. & Figueiredo, F. B. Leishmania spp. in indigenous populations: A mini-review. Front. Public Health 10, 1033803 (2022).

Willi, B. et al. Development and application of a universal hemoplasma screening assay based on the SYBR green PCR principle. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47, 4049–4054 (2009).

Maggi, R. G., Mascarelli, P. E., Havenga, L. N., Naidoo, V. & Breitschwerdt, E. B. Co-infection with Anaplasma platys, Bartonella henselae and Candidatus Mycoplasma haematoparvum in a veterinarian. Parasites Vectors 6, 103 (2013).

Sykes, J. E., Lindsay, L. L., Maggi, R. G. & Breitschwerdt, E. B. Human coinfection with Bartonella henselae and two hemotropic Mycoplasma variants resembling Mycoplasma ovis J. Clin. Microbiol. 48, 3782–3785 (2010).

Steer, J. A. et al. A novel hemotropic Mycoplasma (hemoplasma) in a patient with hemolytic anemia and pyrexia. Clin. Infect. Diseases: Official Publication Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 53, e147–e151 (2011).

Yuan, C. L. et al. Prevalence of Mycoplasma suis (Eperythrozoon suis) infection in swine and swine-farm workers in Shanghai, China. Am. J. Vet. Res. 70, 890–894 (2009).

Compton, S. M., Maggi, R. G. & Breitschwerdt, E. B. Candidatus Mycoplasma haematoparvum and Mycoplasma haemocanis infections in dogs from the United States. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 35, 557–562 (2012).

Beus, K., Goudarztalejerdi, A. & Sazmand, A. Molecular detection and identification of hemotropic Mycoplasma species in dogs and their ectoparasites in Iran. Sci. Rep. 14, 580 (2024).

do Nascimento, N. C., Santos, A. P., Guimaraes, A. M., Sanmiguel, P. J. & Messick, J. B. Mycoplasma haemocanis–the canine hemoplasma and its feline counterpart in the genomic era. Vet. Res. 43, 66 (2012).

Fernandes, A. J. et al. Hemotropic mycoplasmas (hemoplasmas) in wild boars, hunting dogs, and hunters from two Brazilian regions. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 69, 908–912 (2022).

da Vieira, R. F. & MOLECULAR INVESTIGATION OF HEMOTROPIC MYCOPLASMAS IN HUMAN BEINGS, DOGS AND HORSES IN A RURAL SETTLEMENT IN SOUTHERN BRAZIL. C. et al. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. Sao Paulo 57, 353–357 (2015).

Soto, F. et al. Occurrence of canine hemotropic mycoplasmas in domestic dogs from urban and rural areas of the Valdivia Province, southern Chile. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 50, 70–77 (2017).

Di Cataldo, S. et al. Widespread infection with Hemotropic Mycoplasmas in Free-ranging dogs and wild foxes across six bioclimatic regions of Chile. Microorganisms 9, 919 (2021).

Happi, A. N., Toepp, A. J., Ugwu, C. A., Petersen, C. A. & Sykes, J. E. Detection and identification of blood-borne infections in dogs in Nigeria using light microscopy and the polymerase chain reaction. Vet. Parasitol. Reg. Stud. Rep. 11, 55–60 (2018).

Fayos, M. et al. Detection and characterization of hemotropic mycoplasmas in Iberian wolves (Canis lupus signatus) of Cantabria, Spain. Infect. Genet. Evol. 124, 105659 (2024).

Willi, B. et al. Haemotropic mycoplasmas of cats and dogs: Transmission, diagnosis, prevalence and importance in Europe. Schweiz. Arch. Tierheilkd 152, 237–244 (2010).

Maggi, R. G. et al. Infection with hemotropic Mycoplasma species in patients with or without extensive arthropod or animal contact. J. Clin. Microbiol. 51, 3237–3241 (2013).

Doline, F. R. et al. ToxopGondiigondii exposure in Brazilian indigenous populations, their dogs, environment, and healthcare professionals. One Health. 16, 100567 (2023).

Santarém, V. A. et al. One health approach to toxocariasis in Brazilian indigenous populations, their dogs, and soil contamination. Front. Public. Health. 11, 1220001 (2023).

Farinhas, J. H. et al. One Health approach to Coxiella burnetii in Brazilian indigenous communities. Sci. Rep. 14, 10142 (2024).

Santarém, V. A. et al. Seroprevalence and associated risk factors of strongyloidiasis in indigenous communities and healthcare professionals from Brazil. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 17, e0011283 (2023).

WideSeq. https://genomics.rcac.purdue.edu/cgi-bin/index.cgi?service=WideSeq&only=O

Kattoor, J. J., Nikolai, E., Qurollo, B. & Wilkes, R. P. Targeted next-generation sequencing for Comprehensive Testing for selected Vector-Borne pathogens in canines. Pathogens (Basel Switzerland) 11, (2022).

RealPCR Tests—Exclusively from IDEXX Reference Laboratories - IDEXX Australia. https://www.idexx.com.au/en-au/veterinary/reference-laboratories/idexx-realpcr-tests/

R CORE TEAM, R. A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (AustriaR Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors kindly thank the Indigenous Special Health District (DSEI), Special Secretariat of Indigenous Health (SESAI), the Indigenous leaders of all communities, Fernando Rodrigo Doline and João Henrique Farinhas for helping with the sample collection and follow-up information.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.B.K., R.P.W., J.B.M., A.P.S., A.W.B., made substantial contributions to the conception; L.B.K. and A.W.B. designed the study; L.B.K., P.S., A.W., J.J.K., M.J., R.P.W., R.G., V.A.S. conducted the analysis, L.B.K., R.P.W., J.B.M., A.P.S., A.W.B., interpreted the data; L.B.K., A.P.S., A.W.B. drafted the article. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kmetiuk, L.B., Shaw, P., Wallington, A. et al. Hemotropic mycoplasmas (hemoplasmas) in indigenous populations and their dogs living in reservation areas, Brazil. Sci Rep 15, 7973 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87938-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87938-0

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Molecular Survey and Phylogenetic Analyses of Canine Hemoplasma Species in Different Parts of Türkiye

Acta Parasitologica (2025)