Abstract

Combining artificial intelligence with static analysis is an effective method for classifying malicious code. Due to the development of anti-analysis techniques, malicious code commonly employs obfuscation methods like packing, which result in garbled assembly code and the loss of original semantics. Consequently, existing pre-trained code language models are rendered ineffective in such scenarios. Current research addresses this issue by converting malicious bytecode into grayscale images and extracting visual features for classification. However, this process truncates the original sequence, compromising its coherence and structure. Furthermore, the image dimensions undergo compression and cropping based on the model’s input requirements, leading to the loss of intricate details. Our solution is a lossless encoding method for the visual structure of code, enabling unrestricted processing of malicious code images of any size. We convert bytecode files into semantically lossless images with proportional width. Then, we use image interleaving encoding to address semantic truncation issues caused by traditional image preprocessing methods. This method also prevents the loss of original code information due to image cropping or compression. For feature extraction, our goal is to combine the lossless encoding results with both local receptive field features and global contextual features. For local features, we achieve uniform embedding of variably sized input samples into equally sized feature maps using a multi-scale feature extraction module. For global contextual features, we reframe the feature maps along the row dimension, treating them as long-text sequences embedded in a matrix. We segment the feature maps into multiple row patch blocks and modify the Transformer’s input components to cache and merge the hidden states of each block. Comparative experiments on various malware datasets demonstrate the effectiveness of our method, consistently achieving outstanding performance across classification metrics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The increasing risk of malicious code attacks have become a persistent global threat known as Advanced Persistent Threats (APTs)1 for internet users worldwide. As the quantity of malicious code continues to grow, the families and variations are also evolving. Due to its complex and versatile functionality, malware can be classified into various malicious families such as adware, trojans, backdoors, ransomware, spyware, and worms based on its expected platform, type, authorship, and other distinguishing features2. Additionally, within malicious code families, subseries and variants can be further divided based on various factors, such as the malicious code library and development group3.

In scenarios where Windows systems are targeted, attackers often inject malicious code into Windows executable files (PE files)4. To evade antivirus detection, malware developers employ various code obfuscation techniques, such as dead code insertion, code packing, and instruction reordering, to hinder security analysts from conducting normal reverse analysis5. As code obfuscation techniques evolve, accurately identifying and classifying malicious code with existing methods becomes exceedingly difficult. Therefore, developing more efficient and robust techniques for analyzing the homology of malicious code families and accurately analyzing malware files is crucial for defending against similar malware from the same family.

Excellent code classification models extract hard-to-detect information like that from code obfuscation. Thus, sophisticated feature engineering is needed. Malware classification can be done via static analysis, dynamic analysis, or combined AI technologies based on the extraction process6. Dynamic analysis requires executing the sample to record and analyze its behavior, increasing both model and operational complexity, while static analysis can evaluate a sample’s contents without execution7.

The classification of malicious code is closely linked to the discovery of new and unknown malware8. Traditional approaches to malicious code detection based on signatures or heuristics are not our focus9. According to McAfee’s research10, security service providers encounter low detection rates when managing large volumes of data for malware classification using traditional methods. Therefore, we are more interested in novel malicious code classification technologies that combine feature engineering and Deep Learning (DL), often incorporating signature information in the feature extraction process. Furthermore, more attackers are encrypting their malicious code, making it increasingly difficult to extract functional information through reverse engineering. This challenge renders existing pre-trained language models incapable of capturing malware features from assembly code. To address this problem, we propose converting the core bytecode of the program into images, and artificially package the byte code sequence into a two-dimensional matrix and apply Computer Vision (CV) techniques for processing11. Figure 1 depicts the basic framework for various malware classification methods using image processing.

Within this basic framework, numerous DL-based code-to-image malware classification methods have been proposed. These studies can be categorized into two main process nodes for further enhancement. The first involves improving the code sequence-to-image processing by generating diverse image representations beyond grayscale images, such as generating Markov images12, histograms13, entropy graphs14, or by allocating additional code information to other RGB channels for storage15. These methods produce mixed images with more visually interpretable features through manual or automated interventions, aiding the model in learning more visual information than simpler images provide. The second node focuses on enhancing the feature extraction process, for example, by using more effective classifiers or cascading multiple DL models for joint learning16. All these methods share a common goal: to assist the model in extracting visual information from grayscale images more comprehensively through improved manual or automated techniques.

Although the code-to-image conversion method is well-suited to DL technology, there are inherent problems that have not yet been resolved. First, while the code sequence possesses coherence, converting code to pixels disrupts this sequence based on the manually set image width. This disruption results in the original code sequence being rearranged, causing adjacent items, such as lines of code, to be separated at opposite edges of the image, thereby disrupting local receptive field coherence. We refer to this defect caused by code-to-image processing behavior as the problem of semantic truncation. Additionally, during the processing of code-visualized images, the image must be resized and cropped to fit the DL network’s input length. This resizing and cropping can result in the omission of structural features, thereby reducing model accuracy17. These issues have been overlooked in prior research.

Our primary idea stems from DL-based image classification and text sequence feature embedding. In image classification, capturing the structural information of code images is crucial. In text sequence feature embedding, extracting the semantic features of malicious code is a challenge that the contextualized word embedding model needs to address. This paper specifically addresses two main issues.

-

How can we address the issue of semantic truncation that occurs during the code-to-image conversion process?

-

How can we make the model truly learn how to classify different types of malicious code, rather than simply overfitting?

To address these challenges, we propose a novel code-lossless encoding scheme. This scheme conveys all bytecode information of malicious code into a generated image while maintaining the correlation between code texts by arranging pixel positions. For instance, utilizing higher-precision pixel data allows for distinguishing similarities within the same malware family and nuances among different families. Given that nearly all malware samples use packing techniques to conceal their code semantics, this method can detect code family classification issues under code obfuscation patterns, revealing visual information overlaid with obfuscated code fragments and original bytecode. Additionally, we employ multiple models in the feature extraction process to extract and recombine visual features at different stages, with each model suited to processing our newly designed code-visualized images.

In summary, the significance of our contributions are as follows:

-

We have proposed an interleaved encoding strategy for code-visualized images that significantly reduces information loss and semantic truncation during the image compression and cropping processes involved in converting code sequences to images. Additionally, this approach enhances semantic coherence in code-visualized images, albeit with a linear increase in computational space complexity.

-

We have developed a strategy for extracting features of malicious code by employing proportional multiscale convolutions to embed and integrate images. This approach produces feature maps containing information from various receptive fields. The spatial pooling operation within this strategy maintains consistency in the row dimensions of the embedded code-visualized images, regardless of their size.

-

We have developed a row-patch-based attention mechanism that divides code feature maps of varying row heights into multiple feature submaps of identical sizes. Additionally, we utilize a caching mechanism to transfer the hidden layer parameters of the Transformer Encoder between neighboring feature submaps. This enables the end-to-end model to handle malicious code-visualized images of any size and generate features with consistent dimensions.

Motivation

Current DL techniques typically extract features from code in order to detect malicious code, but methods for feature extraction rely on pre-defined rules to identify specific key features. Due to the complexity of code, some malicious code may be deeply hidden and cannot be detected or categorized into malicious families solely by relying on pre-defined key features.

A growing trend in detecting malicious software involves utilizing image-processing and classification techniques. This approach circumvents the need for complex analysis of assembly code or behavior. By representing malware as images, these methods can withstand known anti-analysis techniques; minor byte modifications do not affect the overall image structure, while significant changes alter the expected behavior or characteristics of the malware. Image-based research is advantageous due to its natural, rapid generation and adaptability to minor modifications in malware. However, current conversion techniques fail to capture the semantic and spatial information of the malicious software.

For instance, some studies18,19 compress and crop grayscale images of code using traditional image classification techniques, while others wrap the byte vector corresponding to the binary with carriage returns to fit into rectangular images20,21,22. This results in nearby code no longer corresponding to adjacent pixels, a phenomenon we refer to as semantic truncation. Hence, we pose the question: “How can we address the issue of semantic truncation that occurs during the code-to-image conversion process?” To answer this question, we must first understand how DL models extract semantic information from malicious code.

The semantic information of code typically represents the writing order and functionality within the code, often following a top-down structure due to human programming habits. The ultimate goal of DL models is to simulate the way humans read code and grasp code’s structure and readability. The introduction of the Transformer model23 addressed the issue of long-distance dependencies in Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) by employing position encoding and attention mechanisms. The aforementioned models require the input to be in sequence format to learn code semantics. However, when converting code to images, the input becomes a matrix with length and width dimensions, rather than a sequence. Consequently, using image feature extraction methods such as 2D convolution is insufficient, as adjacent rows of pixels in the code image do not correspond to adjacent code snippets. The longer the width set manually, the greater the distance between adjacent rows of pixels when restored to the code. Thus, it is necessary to focus on the connections between pixels along the same row in the horizontal direction, rather than merely processing the code-visualized images in the same way as traditional images.

Additionally, beyond code-to-image approaches, recent studies have explored representing malicious software as graphs. For instance, Yin et al. 24 propose a “code-to-graph” framework to discover malicious signatures by analyzing structural interactions, leveraging a network topology to capture function-call or data-flow relationships. Such graph-based methods address certain limitations of image-based representations by preserving more explicit control-flow and data-flow semantics, although they may incur higher complexity in graph construction and graph neural network training.

We have observed a phenomenon where many studies report astonishingly high accuracy rates of 99.3% to 99.9% in their evaluations, indicating a potential risk of overfitting in classification models. Most malware classification algorithms extract features of malicious software (such as meta-data, TF-IDF, or N-gram)25 and project all inputs into the same feature space using DL models. Machine learning methods such as Ada-boost and decision trees are then used to classify malware, achieving high accuracy in such classification. However, these methods are only effective when a great amount of labeled data is available for supervised learning algorithms. Moreover, such models do not truly enable the understanding of the essence of malicious code; instead, they use numerous parameters of network layers to implicitly store the features of each sample. This approach is not much different from traditional signature-based classification methods that rely on retrieving signatures from a database

Therefore, we pose the second question: “How can we ensure the model genuinely learns to classify different types of malicious code rather than merely overfitting?” To answer this, we must redesign a visual feature-based framework for malware classification. First, we need to address the issue of significant overfitting or convergence when dealing with rare variants or newly detected types of malware due to data scarcity. Second, we need to overcome the challenges posed by using code-visualized images of malware as feature inputs. In some cases, new malware variants produced by code obfuscation techniques are treated as sample noise when creating code-visualized images, leading to inaccurate classification of variants from the same malware family. Additionally, code-visualized images of malware files have different sizes and shapes. When using them as input for visual models, a significant amount of original malicious information is lost due to the need for scaling, particularly downsampling to the same dimensions. Accurately classifying numerous variants from the same malicious software family remains a significant challenge.

In short, our primary objective is to enhance malware classifier’s ability to distinguish between malware families by creating code structure images with lossless encoding and employing effective feature extraction techniques.

Relate work

Most traditional malware classification studies utilize static or dynamic analysis techniques to extract features and classify malware based on similarity measurement algorithms. However, as the variety, quantity, and detection difficulty of malware continue to increase, the limitations of these methods have become apparent. To enhance the efficiency and accuracy of malware detection, researchers have begun exploring methods that combine malware visualization techniques with feature embedding techniques in DL. This paper details recent advances that integrate language models and visual models, including analysis methods based on malicious code text sequences and techniques that combine malware images with DL.

Models based on malicious code text

Sequence-based methods measure similarity from various perspectives, including string-based approaches26,27,28, tree-based approaches29, token-based approaches30,31, graph-based approaches32,33,34, and hybrid deep learning models35,36. Jeon et al.37 employed a method based on Convolutional Recurrent Neural Network to classify malware code. Ding et al.38 addressed the issue of malware classification on imbalanced datasets by adding a self-learning mechanism for malware family weights to the classification model through the analysis of malware ASM files. Chong et al.39 tackled malware classification from raw byte sequences by constructing a 1D-CNN neural network.

Recent studies have demonstrated that embedding assembly code using Transformer-based models effectively captures long-range dependencies and contextual relationships, thereby enhancing the accuracy and efficiency of malicious code classification. Gui et al.38 introduced a function embedding scheme using pre-training aligned assembly, which improves precision and malware analysis effectiveness through a self-attention mechanism and graph convolution network model. Wang et al.40 designed a binary code embedding framework called sem2vec, which effectively uses symbolic execution and graph neural networks for robust malware detection across various compilers and obfuscation methods. Zhu et al.41 proposed a novel transformer-based model that incorporates domain knowledge into binary code embeddings, significantly improving performance on tasks like binary code similarity detection and function type recovery. Lee et al.42 provided a comprehensive review of malicious code detection techniques, emphasizing the growing sophistication of APT attacks and the necessity for advanced detection methods, including the use of Transformer-based models to enhance detection capabilities.

However, obtaining information like opcodes and API calls requires reverse engineering of the malicious code, and the feasibility of such methods is diminished by existing software encryption and obfuscation techniques. Furthermore, distribution biases in the training and testing datasets pose challenges for the trained model to generalize to real-world data distributions.

Models based on malicious code images

Converting bytecode into grayscale images and using visual models for malware classification offers advantages over direct analysis of assembly code. Visual models can capture and learn texture and structural patterns within images, which often indicate malicious behavior and anomalies. This approach reduces reliance on specific code details, allowing for a broader and generally more effective detection of various malware variants. It minimizes dependence on particular opcode sequences or syntactic features, which can vary significantly across different malware families, allowing for more nuanced and effective detection of subtle variations and patterns indicative of malicious activities.

The majority of approaches43,44 use grayscale images directly derived from the binary sequences of malicious software. For instance, Cui et al.45 transform the binary sequences of malicious software into grayscale images and classify them using CNN. As CNN requires images with uniform dimensions, they truncate executable files to a standardized length, ensuring that the transformed images have the same size suitable for the network input. Verma et al.46 propose an innovative combination of gray-level co-occurrence matrices and statistical texture features. On the other hand, Vasan et al.47 propose using the knowledge obtained from pre-training large parameter models on ImageNet for classification, including VGG and ResNet. Xue et al.48 use static analysis method to obtain grayscale images and utilize a CNN model with a specialized structure for classification, incorporating a spatial pyramid pooling (SPP) layer. Nisa et al.49 complete the malware classification task using pre-trained image classification models such as AlexNet and InceptionV3. Recently, alternative forms of malware images other than grayscale have been proposed for malware classification.50,51. Ni et al.52 extract opcode sequences from the malware and generate SimHash-based grayscale images from these sequences, then classify them using CNNs. Vu et al.53 use mixed-color encoding on the source code, making use of byte entropy and syntactic attributes. Consequently, compared to binary and opcode sequences, these images can offer more comprehensive information about malicious software assembly instructions.

Methodology

In this section, we present our innovative and efficient model for malicious code classification.

Overview

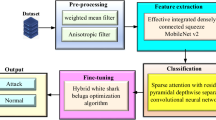

The framework comprises four primary phases, as depicted in Fig. 2: bytecode image conversion, image interleave coding, image feature embedding, and row patch attention learning.

-

Bytecode Image Conversion: The initial steps involve devising semantic lossless encoding methods to formulate the code-to-image transformation strategy. The model then encodes the bytecode file into a code-visualized image, thereby preserving all information without incurring any loss.

-

Image Interleave Coding: The first and second sub-coded images are obtained by appending pixel rows. Specifically, each row of the first sub-coded image is spliced with the corresponding row from the subsequent image pixel.

-

Image Feature Embedding: Based on the visual feature extraction model, we perform multi-scale feature extraction on the interlaced code-visualized images, thereby transforming them into feature maps.

-

Row Patch Attention learning: The final stage focuses on classification. Using the feature map generated in the previous step, we train a row patch Transformer model to classify the malicious code family.

Bytecode image conversion

To achieve lossless encoding and preserve the original information in the code under test, we utilize a mainstream method that involves converting each byte value in the code into a corresponding pixel value. This approach allows for the extraction of more comprehensive features from the code-visualized image, thereby ensuring the accuracy of subsequent malicious code classification. In other implementation methods, it might not be necessary to convert all byte values into pixel values to enhance encoding efficiency or meet the input scale requirements of CV-based DL models. Common practices in CV include cropping and resizing, which can be analogous to converting only a portion of the byte values into pixel values.

Using a fixed-size encoding image for codes of varying scales can lead to substantial information loss. Malicious code with large data volume, for instance, may lose crucial features during conversion. Our proposed solution involves generating encoding images that correspond to the size of the code under examination. This approach effectively mitigates the information loss caused by compression and cropping during the code-to-image representation process.

Due to potential variations in the byte sequence length of different tested malicious codes, the encoded code image size must be directly proportional to the original code’s bytecode length to preserve all information. In other words, larger codes under test correspond to larger encoding images. This enables the encoding image to encompass more original information about the code being tested. For instance, encoding all byte values into corresponding pixel values results in an encoded image that retains all the original information of the code without any noticeable loss, thus achieving lossless encoding. The upper part of Fig. 3 illustrates the key steps of bytecode image conversion.

Specifically, for the PE malicious code dataset D, we select the sample \(S_{max}\) with the maximum code length and the sample \(S_{min}\) with the minimum code length. We then obtain the total byte count \(B_{max}\) from sample \(S_{max}\) and the total byte count \(B_{min}\) from sample \(S_{min}\). Next, we apply \(B_{max}\) and \(B_{min}\) to the formula

to calculate \(n_{max}\) and \(n_{min}\). By doing so, we establish that for any sample in the PE malicious code dataset, the scale of the resulting square image always fall between \(2^{n_{min}}\) and \(2^{n_{max}}\). Consequently, we define the set of column widths for this dataset as \(W=\{2^{n_{min}},2^{n_{min}+1},...,2^{n_{max}}\}\), thereby constraining the input image column width to be a power of 2 and maintaining geometric proportionality among column widths.

Subsequently, each byte value in any malware code file is mapped to a grayscale range. This is achieved using the grayscale transformation formula: \(g=byte/255\). This formula normalizes the byte values (integers in the range of 0 to 255) to grayscale values between 0 and 1. Here, number 0 represents black, while number 1 represents white. The variable g represents the grayscale value, denoting the brightness of the pixel, with a range between 0 and 1. After converting each byte value to its corresponding grayscale value, the grayscale values are arranged in the original malicious code’s encoding sequence, forming the grayscale queue \(Q=\{g_1, g_2, g_3, \ldots , g_{B_i}\}\). Here, \(B_i\) represents the number of byte codes in the malware code file, and \(g_k\) denotes the k-th element in the queue Q, representing the k-th grayscale value.

After obtaining the grayscale queue of the malicious code in the previous step, we calculate the arithmetic square root of the number of elements in the queue, denoted as \(\sqrt{B_i}\). We rearrange the original bytecode into an image with equal column width. Specifically, we calculate the absolute difference between each candidate column width element in the set W and the square root of the current bytecode pixel \(\sqrt{B_i}\)

By using Equation 2, we can find the element that minimizes the difference and obtain the column width \(w_i\) closest to \(\sqrt{B_i}\). In case of equal differences, we choose the larger value from the set W to reduce the length of the image and decrease the frequency of semantic truncation. We create a blank grayscale image with a width of the selected column width w and a height of the number of rows in the code sample, which is equal to \(h = \lceil \frac{{B_i}}{{w_i}} \rceil\). By rounding up the number of rows, we ensure that all elements in the grayscale queue Q can be losslessly encoded into the image. We traverse each row of the image, obtain the position of the current pixel, determine the corresponding character position based on the current row and column index, retrieve the corresponding grayscale pixel value from the queue Q, fill the grayscale pixel value into the current pixel position of the image, and dequeue the pixel value from the queue. We repeat the above steps until all rows have been traversed. The resulting grayscale image \(G \in \mathbb {R}^{w \times h}\) is the structured representation with fixed column width, where h is the height (row dimension) of the image and \(w \times h \ge B\).

Since the total number of bytecode in each malicious code is different, malicious codes with bytecode sizes within the interval \([{2^{{w_i}}},{2^{{w_i}}} + {2^{{w_i} - 1}})\) would be generated as grayscale images with similar row widths and the same column width. For malicious codes with varying bytecode sizes, their column widths differ. However, since the candidate column width elements are selected from a geometric sequence, all malicious code samples in the dataset can be generated as images with equal column width. The images contain all grayscale pixels and can be losslessly compressed to preserve the original information in the bytecode. Finally, we fill in the pixel values converted from the byte values of the code being tested into the grayscale image to obtain the encoded image. This maintains the correlation between the bytes in the code being tested and the positions of the pixels in the encoded image.

Image interleave coding

Bytecode files are essentially text sequences expressed in a specialized “natural language,” featuring strong semantic coherence and strict structural rules for every character and symbol. Building on the lossless code representation obtained previously, our goal here is to ensure that the model can extract feature maps reflecting these semantic relationships.

Figure 3 (lower part) outlines the key steps. First, we create a “code structure siamese image,” \(G_c = G\), which is an identical copy of the original code structure image \(G\). We then perform a downward shift on \(G\) by appending a row of padding symbols \([pad]\) (of size \(1 \times w\)) at the bottom. This shifted image, \(G' \in \mathbb {R}^{w \times (h+1)}\), becomes our first sub-coded image.

Simultaneously, we do an upward shift on the siamese image \(G_c\), again adding a \(1 \times w\) row of \([pad]\) but at the top. The resulting \(G'_c \in \mathbb {R}^{w \times (h+1)}\) becomes our second sub-coded image. Finally, we align and concatenate these two sub-coded images horizontally, row by row:

where \([\,;\,]\) denotes horizontal concatenation. The resultant matrix \(G^*\) has dimensions \(\mathbb {R}^{2w \times (h+1)}\).

Optionally, we can place a predefined element at the top and bottom rows of this newly formed image to ensure that the end of each row in \(G'\) connects seamlessly to the start of the corresponding row in \(G'_c\). This strategy counters “semantic truncation” caused by line wrapping in the original image. By preserving row-to-row coherence across sub-coded images, our approach better retains the natural flow of the code. As a result, the subsequent multi-scale feature extraction phase can capture meaningful code semantics more accurately.

A predefined element can be added to the top and bottom rows of the encoded image. This allows for the seamless concatenation of the first and second sub-encoded images, ensuring that the end of each row in the first encoded image merges with the beginning of the corresponding row in the second encoded image. Consequently, this addresses the issue of semantic truncation caused by pixel line breaks in this approach. By enabling coherent code semantic features to be extracted, we can ensure the accuracy of feature extraction in the multi-scale feature extraction process using the concatenated encoded image.

Image feature embedding

After generating a new code structure image, the end of each row in the original image is concatenated with the beginning of the next row. This enables local feature extractors to learn coherent code semantic features. Given the varying sizes and aspect ratios of code-visualized images in the dataset, a specifically designed structure for the code feature extractor is necessary to ensure the batch processing capability of input data, maintain feature consistency, and enable efficient computation and parameter sharing.

Sequence inception layer: Based on the number of bytes in the code under test, we determine the convolution kernel that matches the encoded image. Using the determined kernel, we extract multi-scale features from the encoded image to obtain multi-scale features of the code under test. In some implementations, different convolution kernels can be pre-set for selection, such as kernels with different numbers and/or different strides. Then, based on a certain rule, different ranges of byte counts can be corresponded to different convolution kernels, allowing the selection of the kernel that matches the code under test. In the above implementation process, as the scale of each code under test may vary, the size of the corresponding generated encoded image may also be different. To adapt to the processing of encoded images of different sizes, multiple different convolution kernels can be set in this solution, allowing the selection of the kernel that corresponds to the byte count of the code under test. This can better capture the feature diversity of the encoded image at different scales. Specifically, the uniform width of the code feature map is defined as the minimum element in W, i.e., \(2^{n_{min}}\). A multi-scale one-dimensional convolution kernel is defined, consisting of a set of convolution kernels with different sizes, denoted as \(K= \{K_1,K_2,...,K_{n_{max}-n_{min}+1}\}\). The sizes of the kernels \(K\in \mathbb {R}^{1 \times k}\) are the ratios of each element in W to \(2^{n_{min}}\), which are used to construct a multi-scale and proportional convolution kernel. The number of convolution blocks is variable, but assumed to be 1 in this scenario.

Subsequently, we calculate the designed proportional 1-D convolution kernel by row pixels, following these specific steps: defining stride and padding, determining the stride of each convolution kernel operation. The stride determines the distance that the convolution kernel slides on the input image. To ensure the uniformity of the feature map in width, the stride of any convolution kernel \(K_i \in \mathbb {R}^{1 \times k}\) is equal to the size of the kernel, i.e., k. Therefore, the convolution features calculated using kernel \(K_i\) can be represented as

Where \(b\in \mathbb {R}\) represents the bias term in the model. \(\alpha\) denotes the non-linear activation function used in the model, while \(G^*[*, i, i+k]\) denotes the pixel sequence operation window in the code structure image matrix. The result of the operation is finally represented as a matrix, with each element being the product of corresponding elements in \(G^*\) and K. For each sample in the malicious code dataset, it is selectively fed into a CNN model with \(n_{max}-n_{min}+1\) different convolution kernel sizes.

For an image \(G^*\) with width \(w=2^{n_{max}}\), convolution blocks are used to obtain convolutional features \(\{C_{1},C_{2},...C_{n_{max}-n_{min}+1}\}\). The above operations enable the capturing of the diverse features of the code structure image at different scales, thereby improving the model’s performance. On the other hand, the multi-scale convolution operation enables the small-scale convolution kernel to focus on the internal information of the original malicious code samples (i.e., those samples with the least byte code compared to other samples in the same malicious code family). The large-scale convolution kernel contains the contextual semantic information of the complex malicious code samples (i.e., those samples with more byte code than other samples in the same malicious code family), which is expanded based on the original malicious code. This significantly enhances the model’s semantic perception of complex code within the malicious code family.

Pooling and fusion: The code-visualized image generates multiple feature maps based on its own size, with the feature sizes within and between samples not being equal. In order to convert them into a unified column width feature map representation and increase channel depth and unify model parameter size, we need to fuse the multi-scale features of this code. The specific steps are as follows: After the previous step is completed, for each feature map generated by any image, use pooling operation to downsample it to the target width size \(w=2^{n_{min}}\). If the size of the feature map is already \(2^{n_{min}}\), use the original feature map directly. For other feature maps, apply the average pooling method, where both the pooling window and stride size are k. The average pooling operation divides the input sequence into non-overlapping pooling windows and calculates the average value of each element in the window as the output. The output sequence of the pooling operation can be represented as

Where \(C{(i-1)k+j}\) denotes the element at position \((i-1)k+j\) in the input sequence, and so on. Each feature map of different scales is pooled using the above steps, downsampling them to a unified new feature map shape with a width of \(2^{n_{min}}\). Then, the fused operation is performed by element-wise summation of the adjusted feature maps to fuse them into a new feature map

Where \(n=\frac{w}{{{2^{{n_{min}} - 1}}}}\), and the feature map dimension is \({F_{\mathrm{{fused }}}}\in \mathbb {R}^{2^{n_{min}} \times (h+1)}\).

Row patch attention learning

By following the aforementioned phases, our approach can transform all feature maps to the same width size, while the length h of the feature map for each sample remains different, necessitating the extraction of correlations between rows in the feature map. Due to the difference between code-visualized images and traditional natural images, which consist of folded and concatenated bytecode text sequences. This coding rule leads to strong correlations between feature points in the horizontal direction (left to right). However, the correlations between pixel points in the vertical direction are relatively weak. This is because the relationship between adjacent pixel points in each row is represented by adjacent characters in the code, whereas the relationship between adjacent pixel points in each column is represented by characters separated by hundreds of lines of code. This distance, related to the column width in the image, makes the correlations between pixel points in columns different from those in traditional images. Therefore, using 2-D convolution to capture local features between columns and rows is not reasonable.

Considering that the feature map after the previous phase is consistent in the column dimension, and referring to the processing method of variable-length sequences in the Transformer Encoder model54, we further design self-attention based on feature map’s row patch blocks. Specifically, for feature maps with different lengths, the row vector set of the feature map can be regarded as a special encoding sequence. Firstly, all samples in the dataset D are clustered and divided according to the column width set. Therefore, sub-datasets \(D= \{D_1, D_2, \ldots , D_{n_{max}-n_{min}+1}\}\) can be obtained. According to the processing method of the code in the first stage, it can be known that each sample in the same sub-dataset \(D_i\) is roughly similar in the h dimension. Selecting the longest row height closest to the power of 2 as \(h^i_{max}\) of each sample in \(D_i\), padding the samples in the dataset whose length is less than \(h^i_{max}\) with bottom padding rows until the length is consistent, and treating this kind of sub-dataset as input in the same batch.

Although the relationships between row vectors in malware code images are relatively weak, these images still have global structural features. On the one hand, attackers currently use obfuscation techniques to protect the security of malware files and prevent them from being reverse analyzed. Therefore, extracting global features can enable the model to learn the structural differences between code structure images and other code-visualized images in the same family, thus capturing the deep spectral features of images produced by packing and obfuscation, and solving the problem of misclassification of malicious PE families caused by the code integrity protection measures designed by attackers, thus improving the model’s resistance to interference. On the other hand, with regard to malware files such as PE files, their structure comprises four relatively independent components: the DOS header, the PE header, the section table, and the section data, each with distinct attribute information. Therefore, code-visualized image also exhibit a vertical (top-to-bottom) feature correlation.

In order to fully extract local information between adjacent rows and global correlations between section tables of malware files, inspired by the inherent structure of PE files, we further divide the fused feature map \(F_{\mathrm{{fused}}}\) into N sub-blocks \(F_{\mathrm{{fused }}}=[S_1\;S2...S_N]^T\) from top to bottom according to the row dimension \(h_{seg}=2^{n_{min}}\), and input each sub-block into the Transformer model step by step. The attention transmission between sub-blocks is replaced by caching the end hidden layer parameters of the previous sub-block, which can effectively process long sequences by passing the hidden state between sub-blocks through the caching mechanism. The implementation method of the caching mechanism is as follows.

-

1.

Initialize the model: In the initial state of the Transformer model, the hidden state \(h_0\) is a tensor of zeros with shape \(h_0 \in \mathbb {R}^{bs, nl, 2^{n_{min}}, 2^{n_{min}}}\), where bs represents the batch size and nl represents the number of layers in the model.

-

2.

The input of the first block of the encoder: To begin with, the first block \(S_1\) of the input sequence is input into the Encoder. The hidden state \(h_0\) of the first block of the encoder is calculated by self-attention with the input of block \(S_1\), and the output hidden state \(h_1\) of block \(S_1\) is obtained.

-

3.

Cache the hidden state: When processing block \(S_1\), the model caches the hidden state \(h_1\) and uses it as the input for the next block. The cached hidden state \(h_1\) has the same shape as the original hidden state \(h_0\) and can be reused when processing the next block.

-

4.

Input of the next block: Next, the second block \(S_2\) of the input sequence is input into the encoder. At this time, in addition to calculating the self-attention with the input of block \(S_2\), the model also calculates the self-attention between the cached hidden state \(h_1\) and the input of block \(S_2\). In this way, the model can not only consider the dependency relationship of block \(S_2\) when processing block B, but also utilize the information of previous block \(S_1\).

-

5.

Recursively pass the hidden state: In this way, each sub-block of the input code structure feature map can be processed step by step, and the hidden state can be passed between each block. Specifically, for the k-th block \(S_k\), the model uses the input of block \(S_k\) and the cached hidden state \(h_{k-1}\) to calculate self-attention, and obtains the output hidden state \(h_k\) of block \(S_k\). Then, the output hidden state \(h_k\) is cached and used as the input hidden state \(h_{k+1}\) for processing the next block, and so on, until the output hidden state \(h_N\) of the end block \(S_N\) is selected as the encoding output of the fused feature map \(F_{\mathrm{{fused}}}\).

During the training process, it is essential that each batch input of the model consists of samples from clusters of equal width. This approach increases the frequency of samples from different malicious code families within the training batches, thereby enhancing the diversity of the training data. Consequently, it reduces the model’s reliance on specific sample orders, alleviates overfitting, and improves the model’s generalization ability. By adhering to these steps, we can extract feature representations that encompass a greater amount of code and structural information. As a result, in the subsequent MLP & Softmax classifier, existing general similarity calculation methods can be employed to compare the similarity between feature representations, thereby improving the model’s accuracy.

Experiments

Experiment settings

To enhance the reliability of our experimental design, we have selected two publicly accessible datasets containing families of malicious software used in international competitions. These datasets are the BIG-15 dataset55 and the BDCI-21 dataset56 provided by Datafountain. Table 1 shows the relevant content of the BIG-15 dataset, it comprises 9 categories of malicious code families, each malicious sample consists of assembly code (.asm) and binary bytecode files (.byte) generated through the IDA Pro disassembler. The raw data of each bytecode file is represented in hexadecimal format, excluding the PE file header. Table 2 shows the relevant content of the BDCI-21 dataset encompasses 5841 malicious software samples from 10 different families. To maintain consistency between the two datasets, for the BDCI dataset, we have selected 5841 binary file and (.byte) files generated by the disassembler tool IDA ProFootnote 1. for experimentation.

In training our proposed model, we define the sampler function for each batch to randomly select code images of equal width along with their corresponding malware labels, setting the mini-batch size to 32. For images smaller than the maximum length, we achieve the required length by appending [pad] at the bottom of the image. For the number of sequence inception layer, we set four convolutional layers of iteration. For the row patch Transformer unit, we set the hidden size and input size to be 256. We utilize the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 2e-4 for parameter updates. To mitigate overfitting, we apply a dropout rate of 0.2. Each model is trained for 60 epochs. The experiments are executed using the PyTorch 2.0 framework and Python 3.8, conducted on an HPC equipped with four Nvidia Tesla V100 GPUs (each with 16 GB of memory) running CentOS 7.5.

Evaluation metrics

The analysis of malicious code similarity is categorized within the domain of multi-classification problems. To improve the model’s capability in distinguishing malicious code homogeneity, arithmetic metrics serve as the primary criteria for assessing the model’s performance. Specifically, recall, precision, F1-score, and accuracy are calculated for each class of malicious code family. These assessments contribute to the overall macro-precision, macro F1-score, macro-recall of the model. The equations used to compute these four evaluation metrics are as follows.

In this context, TP denotes the count of samples accurately classified as positive, FP indicates the count of samples erroneously classified as positive, FN signifies the count of samples mistakenly classified as negative, TN represents the count of samples accurately classified as negative, and N stands for the total number of samples.

In addition, we have chosen the False Positive Rate (FPR) as a metric:

This criterion is crucial, yet it is often overlooked in evaluations. It refers to the proportion of normal samples mistakenly predicted as malicious samples during the classification process. In other words, the FPR measures the extent to which the classifier generates erroneous alerts on normal samples. In malware classification, lowering the FPR is of utmost importance. A high FPR may result in frequent false alarms for users, negatively affecting their experience and possibly overlooking genuine threats.

Comparison with different models

For the sake of experimental consistency, we conducted a comparative analysis of deep learning models used with these two datasets in recent years, evaluating them against the metrics proposed in this paper. Moreover, given the current absence of research validation for the BDCI dataset, we utilize DL models tested on another Malimg dataset57 for conducting the comparative analysis. Each sample in Malimg dataset is represented as a matrix, with each eight-bit value from the malware binary file converted into an unsigned integer. It is noteworthy that this dataset contains images of varying sizes. During the evaluation with this dataset, baseline models were uniformly resampled to normalize the model inputs and meet the dimensional requirements of backbone models. Therefore, when reproducing experiments with this dataset, we resample the BDCI-21 dataset based on the input specifications of the baseline models.

Experimental results

We utilize both statistical learning and deep learning models on both datasets, in addition to the image classification model applied to the Malimg dataset. Subsequently, we reproduce these models on both datasets following our experimental environment.

The dataset was divided into a 6:4 ratio, with 60% of the data used for model training, and the remaining 40% used for testing. For the statistical learning methods, we opted for K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), XGBoost, and Decision Trees (DT). Regarding the deep learning models, we selected experiments based on recent publications. While the papers did not provide the source code, most of them were built upon widely-used backbone network models such as VGG60, EfficientNet61, and ResNet62, which facilitated the relatively straightforward reproduction of the models in our local environment. Hence, we did not rely on their results directly but instead conducted our own experiments. We utilized multiple vision foundation models as baseline methods to facilitate comprehensive comparative studies.

The comparative experimental data are presented in Tables 3 and 4. Concerning the BIG-2015 dataset, it is evident that deep learning models outperform traditional statistical learning models and achieve notably high metrics. Specifically, our proposed model attains the highest accuracy and F1 values, reaching 96.7% and 95.2%, respectively. Importantly, our method maintains a lower false positive rate, a result of comprehensive input learning during training, incorporating complete statistical properties. This enables the model to fully comprehend the patterns of malicious code across different categories. Furthermore, when considering the Datafountain BDCI-21 dataset, the experimental results indicate that our model outperforms the baseline model, achieving an accuracy of 99.7% and an F1 value of 99.7%. Based on the data, our model surpasses statistical learning methods and six deep learning-based models.

For both the proposed model and the comparison model, we conducted distinct accuracy comparisons across nine different categories in the BIG-15 dataset to evaluate the classification performance of each model under various data distributions. Figure 4 provides a comparison of the proposed approach with selected baselines, using the same training epoch and batch size configurations. Notably, our model achieved an impressive test accuracy, surpassing other baseline methods. Although the prediction accuracy is generally relatively poor for the Obfuscator.ACY and Lollipop malicious family categories in the BIG-15 dataset, our model still exhibits excellent performance.

Figures 5 and 6 display the t-SNE distribution graph, illustrating the utilization of the BDCI-21 dataset as the test set. t-SNE, a widely used dimensionality reduction technique, facilitates the visualization of higher-dimensional data in a lower-dimensional feature space and provides a quantitative measure of data separability. In the graph, each node signifies a sample of malicious software, with distinct colors representing different malicious software families. It is evident that similar samples are grouped together under specific colors, indicating the accuracy of the dataset labeling concerning malicious software families. The visualization results demonstrate that our proposed model makes code-visualized image features more distinguishable, thereby providing a more suitable feature set for model training. As a result, the model training becomes highly efficient, outperforming the performance achieved when training other models.

Figure 7 depicts the confusion matrix obtained by implementing our model on the BDCI-21 dataset. It is evident that the model’s performance has been improved by mitigating biases towards specific families that were previously dominant. As shown in the confusion matrix, illustrating the classification errors across various categories attained by our proposed approach, the matrix reveals that our model makes minimal misclassifications.

Discussion

To explore more deeply how training samples affect performance metrics, we partitioned the training set of the dataset into various proportions, ranging from 10% to 90%. The outcomes are depicted in Fig. 8. As the sample subset diminishes, all models exhibit a certain degree of performance decline, indicating that our model maintains excellent classification efficacy even with a reduced number of training data, which remains relatively unaffected by dataset size variations.

We contend that the genuine challenge in handling limited samples of malicious code does not solely lie in correctly predicting previously unseen families of malicious code, as this often results in overfitting and leads to some papers reporting accuracy rates of over 99%. Conversely, we emphasize that the true test of a robust and generalized malicious code classification model lies in its capability to accurately classify exceptional samples within malicious code families, including cases with extremely minimal bytecode (Image with smaller width) or cases with bytecode quantities far exceeding those of normal executable files (Image with larger width).

We further investigated the impact of limiting input size on the model’s processing of input data. Both datasets were processed using our proposed image encoding method, and subsets were created based on image width. Specifically, in the BIG-15 dataset, images with sizes 256 and 4096 were underrepresented, and in the BDCI-21 dataset, images with sizes 128 and 4096 were also underrepresented. Therefore, we included these subsets entirely in the test set. Subsequently, We conducted separate training using a training set comprising 70% of the data and a test set comprising the remaining 30%. Tables 5 and 6 present the performance metrics for each subset based on width categories. It is evident that the majority of malicious code falls within the range of 512-2048, and our model achieved favorable accuracy and false positive rates across these subsets. Even for the untrained width categories of 128, 256, and 4096, our model demonstrated precise predictions.

Threats to validity

Internal validity

Our model is incapable of conducting ablation experiments due to its highly compact structure. As we input an image with unrestricted dimensions, the outputs of the CNN and pooling fusion layer result in feature maps with uniform width but varying lengths. Then, the row patch Transformer is ingeniously designed, drawing inspiration from the Transformer’s ability to handle variable-length text sequences. Its purpose is to resolve the issue of inconsistent feature map lengths from the previous step, enabling the model’s successful training. Consequently, both modules play significant roles in the feature extraction process.

External validity

We ought to conduct further validation experiments on a broader and more diverse dataset. To ensure experiment reliability, we utilized publicly available malicious software datasets, which might only encompass specific types of malware and malicious behaviors. The model’s impressive performance on these samples does not guarantee its accurate classification and detection of other types of malicious software. Thus, additional experiments should encompass a wider array of samples and malware families.

Conclusion

This paper introduces a novel concept that transforms the source code of malicious software into lossless images, preserving the structural details. This approach overcomes challenges in traditional methods where image compression and cropping lead to information loss and semantic truncation. As a result, it enhances malicious code classification accuracy and reduces false positives. Our proposed approach combines convolutional neural networks and Transformer models, effectively extracting features from malware files of any size and input image scales. The fusion of these techniques empowers the model to handle variable-length sequences and imbalanced data, adapting to new samples and environments. Extensive experiments confirm its strong generalization capability for practical applications.

Data availability

Our code is available at https://github.com/yx-yu/MalwareGraph. The BIG-15 and BDCI-21 datasets are publicly available at https://www.kaggle.com/c/malware-classification/data, https://www.datafountain.cn/competitions/507/datasets.

Notes

The IDA Pro disassembler and debugger: http://www.hex-rays.com/idapro

References

Alshamrani, A., Myneni, S., Chowdhary, A. & Huang, D. A survey on advanced persistent threats: Techniques, solutions, challenges, and research opportunities. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 21, 1851–1877 (2019).

Recap, S. W. Sans webcast recap 2021. [online] (2021). Https://www.vmray.com/cyber-security-blog/challenges-tracking-new-malware-variants-source-code-leaks-recap/.

Yan, S. et al. A survey of adversarial attack and defense methods for malware classification in cyber security. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials (2022).

Mimura, M. Evaluation of printable character-based malicious pe file-detection method. Internet of Things 19, 100521 (2022).

Gibert, D., Planes, J., Mateu, C. & Le, Q. Fusing feature engineering and deep learning: A case study for malware classification. Expert Syst. Appl. 207, 117957 (2022).

Singh, J. & Singh, J. A survey on machine learning-based malware detection in executable files. J. Syst. Architect. 112, 101861 (2021).

Ijaz, M., Durad, M. H. & Ismail, M. Static and dynamic malware analysis using machine learning. In 2019 16th International bhurban conference on applied sciences and technology (IBCAST), 687–691 (IEEE, 2019).

Gopinath, M. & Sethuraman, S. C. A comprehensive survey on deep learning based malware detection techniques. Comput. Sci. Rev. 47, 100529 (2023).

Demetrio, L. et al. Adversarial exemples: A survey and experimental evaluation of practical attacks on machine learning for windows malware detection. ACM Trans. Privacy Secur. (TOPS) 24, 1–31 (2021).

Mcafee. Mcafee labs threats reports. [online] (2021). https://www.trellix.com/en-us/advanced-research-center/threat-reports.html.

Zhao, J., Masood, R. & Seneviratne, S. A review of computer vision methods in network security. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 23, 1838–1878 (2021).

Deng, H., Guo, C., Shen, G., Cui, Y. & Ping, Y. Mctvd: A malware classification method based on three-channel visualization and deep learning. Comput. Secur. 126, 103084 (2023).

Falana, O. J., Sodiya, A. S., Onashoga, S. A. & Badmus, B. S. Mal-detect: An intelligent visualization approach for malware detection. J. King Saud Univ.-Comput. Inf. Sci. 34, 1968–1983 (2022).

Zhu, J. et al. A few-shot meta-learning based siamese neural network using entropy features for ransomware classification. Comput. Secur. 117, 102691 (2022).

Tekerek, A. & Yapici, M. M. A novel malware classification and augmentation model based on convolutional neural network. Comput. Secur. 112, 102515 (2022).

Azeez, N. A., Odufuwa, O. E., Misra, S., Oluranti, J. & Damaševičius, R. Windows pe malware detection using ensemble learning. In Informatics, vol. 8, 10 (MDPI, 2021).

Talebi, H. & Milanfar, P. Learning to resize images for computer vision tasks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 497–506 (2021).

Son, T. T., Lee, C., Le-Minh, H., Aslam, N. & Dat, V. C. An enhancement for image-based malware classification using machine learning with low dimension normalized input images. J. Inf. Secur. Appl. 69, 103308 (2022).

Liu, Y., Li, J., Liu, B., Gao, X. & Liu, X. Malware detection method based on image analysis and generative adversarial networks. Concurr. Comput.: Pract. Exper. 34, e7170 (2022).

Mallik, A., Khetarpal, A. & Kumar, S. Conrec: malware classification using convolutional recurrence. J. Comput. Virol. Hacking Tech. 18, 297–313 (2022).

Kumar, S. & Janet, B. Dtmic: Deep transfer learning for malware image classification. J. Inf. Secur. Appl. 64, 103063 (2022).

Rustam, F., Ashraf, I., Jurcut, A. D., Bashir, A. K. & Zikria, Y. B. Malware detection using image representation of malware data and transfer learning. J. Parallel Distribut. Comput. 172, 32–50 (2023).

Demırcı, D. et al. Static malware detection using stacked bilstm and gpt-2. IEEE Access 10, 58488–58502 (2022).

Yin, C. et al. Discovering malicious signatures in software from structural interactions. In ICASSP 2024-2024 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), 4845–4849 (IEEE, 2024).

Wang, P., Tang, Z. & Wang, J. A novel few-shot malware classification approach for unknown family recognition with multi-prototype modeling. Comput. Secur. 106, 102273 (2021).

Coull, S. E. & Gardner, C. Activation analysis of a byte-based deep neural network for malware classification. In 2019 IEEE Security and Privacy Workshops (SPW), 21–27 (IEEE, 2019).

Aslan, Ö. & Yilmaz, A. A. A new malware classification framework based on deep learning algorithms. IEEE Access 9, 87936–87951 (2021).

Lin, W.-C. & Yeh, Y.-R. Efficient malware classification by binary sequences with one-dimensional convolutional neural networks. Mathematics 10, 608 (2022).

Louk, M. H. L. & Tama, B. A. Tree-based classifier ensembles for pe malware analysis: A performance revisit. Algorithms 15, 332 (2022).

Amer, E. & Zelinka, I. A dynamic windows malware detection and prediction method based on contextual understanding of api call sequence. Comput. Secur. 92, 101760 (2020).

Zhang, B. et al. Ransomware classification using patch-based cnn and self-attention network on embedded n-grams of opcodes. Futur. Gener. Comput. Syst. 110, 708–720 (2020).

Wu, B., Xu, Y. & Zou, F. Malware classification by learning semantic and structural features of control flow graphs. In 2021 IEEE 20th International Conference on Trust, Security and Privacy in Computing and Communications (TrustCom), 540–547 (IEEE, 2021).

Herath, J. D., Wakodikar, P. P., Yang, P. & Yan, G. Cfgexplainer: Explaining graph neural network-based malware classification from control flow graphs. In 2022 52nd Annual IEEE/IFIP International Conference on Dependable Systems and Networks (DSN), 172–184 (IEEE, 2022).

Qiang, W., Yang, L. & Jin, H. Efficient and robust malware detection based on control flow traces using deep neural networks. Computers & Security 102871 (2022).

Hussain, A., Asif, M., Ahmad, M. B., Mahmood, T. & Raza, M. A. Malware detection using machine learning algorithms for windows platform. In Proceedings of International Conference on Information Technology and Applications: ICITA 2021, 619–632 (Springer, 2022).

Li, S. et al. A malicious mining code detection method based on multi-features fusion. IEEE Transactions on Network Science and Engineering (2022).

Jeon, S. & Moon, J. Malware-detection method with a convolutional recurrent neural network using opcode sequences. Inf. Sci. 535, 1–15 (2020).

Li, S., Li, Y., Wu, X., Al Otaibi, S. & Tian, Z. Imbalanced malware family classification using multimodal fusion and weight self-learning. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems (2022).

Chong, X. et al. Classification of malware families based on efficient-net and 1d-cnn fusion. Electronics 11, 3064 (2022).

Wang, H. et al. sem2vec: Semantics-aware assembly tracelet embedding. ACM Trans. Softw. Eng. Methodol. 32, 1–34 (2023).

Zhu, W. et al. ktrans: Knowledge-aware transformer for binary code embedding. arXiv preprint arXiv:2308.12659 (2023).

Lee, K., Lee, J. & Yim, K. Classification and analysis of malicious code detection techniques based on the apt attack. Appl. Sci. 13, 2894 (2023).

Chai, Y., Du, L., Qiu, J., Yin, L. & Tian, Z. Dynamic prototype network based on sample adaptation for few-shot malware detection. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 35, 4754–4766 (2022).

Conti, M., Khandhar, S. & Vinod, P. A few-shot malware classification approach for unknown family recognition using malware feature visualization. Comput. Secur. 122, 102887 (2022).

Cui, Z. et al. Detection of malicious code variants based on deep learning. IEEE Trans. Industr. Inf. 14, 3187–3196 (2018).

Verma, V., Muttoo, S. K. & Singh, V. Multiclass malware classification via first-and second-order texture statistics. Comput. Secur. 97, 101895 (2020).

Vasan, D., Alazab, M., Wassan, S., Safaei, B. & Zheng, Q. Image-based malware classification using ensemble of cnn architectures (imcec). Comput. Secur. 92, 101748 (2020).

Xue, D., Li, J., Lv, T., Wu, W. & Wang, J. Malware classification using probability scoring and machine learning. IEEE Access 7, 91641–91656 (2019).

Nisa, M. et al. Hybrid malware classification method using segmentation-based fractal texture analysis and deep convolution neural network features. Appl. Sci. 10, 4966 (2020).

Pinhero, A. et al. Malware detection employed by visualization and deep neural network. Comput. Secur. 105, 102247 (2021).

Obaidat, I., Sridhar, M., Pham, K. M. & Phung, P. H. Jadeite: A novel image-behavior-based approach for java malware detection using deep learning. Comput. Secur. 113, 102547 (2022).

Ni, S., Qian, Q. & Zhang, R. Malware identification using visualization images and deep learning. Comput. Secur. 77, 871–885 (2018).

Vu, D.-L. et al. Hit4mal: Hybrid image transformation for malware classification. Trans. Emerg. Telecommun. Technol. 31, e3789 (2020).

Vaswani, A. et al. Attention is all you need. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30: Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 2017, December 4-9, 2017, Long Beach, CA, USA, 5998–6008 (2017).

Alessandro Panconesi, W. C., Marian. Microsoft malware classification challenge (big 2015) (2015). https://www.kaggle.com/competitions/malware-classification.

CCF-BDCI. Malware family classification based on artificial intelligence. [online] (2021). https://www.datafountain.cn/competitions/507/datasets.

Nataraj, L., Karthikeyan, S., Jacob, G. & Manjunath, B. S. Malware images: visualization and automatic classification. In Proceedings of the 8th international symposium on visualization for cyber security, 1–7 (2011).

AlGarni, M. D. et al. An efficient convolutional neural network with transfer learning for malware classification. Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing2022, 1–8 (2022).

Parihar, A. S., Kumar, S. & Khosla, S. S-dcnn: stacked deep convolutional neural networks for malware classification. Multimedia Tools Appl. 81, 30997–31015 (2022).

Simonyan, K. & Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv preprint arXiv:1409.1556 (2014).

Tan, M. & Le, Q. Efficientnet: Rethinking model scaling for convolutional neural networks. In International conference on machine learning, 6105–6114 (PMLR, 2019).

Hu, J., Shen, L. & Sun, G. Squeeze-and-excitation networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 7132–7141 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by in part by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.61971316).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Y.X. and C.B. designed the research idea. Y.Y.X and K.A. carried out the experiment. Y.Y.X., K.A., and L.J. constructed the dataset and validated the samples. Y.Y.X. and W.X.Y. wrote the manuscript. P.C., M.S.I., and T.C. performed the analysis and interpreted the results; All authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript. All authors provided critical feedback and helped shape the research, analysis and manuscript.

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, Y., Cai, B., Aziz, K. et al. Semantic lossless encoded image representation for malware classification. Sci Rep 15, 7997 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88130-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88130-0