Abstract

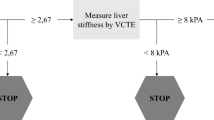

Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm (AAA) poses a significant health risk due to its silent nature and high mortality upon rupture. The Fib-4 index, initially designed for liver fibrosis assessment, presents potential beyond its scope. This study aims to investigate the association of FIB-4 with aneurysm size and mortality risk, exploring its utility as a risk predictor for enhanced clinical management. This retrospective longitudinal research studied 141 AAA open repair surgery patients (92% male, mean age of 70 years (SD: 11.5)) from October 2016 to September 2021 for a median follow-up 35 months (IQR: 0.7 – 56.6). All-cause mortality was the primary outcome. Adjusted hazard ratios (aHR) were calculated for each Fib-4 cut-off between 1.5 and 3.25. FIB-4 cut-off range of 2.58–2.74 was associated with higher mortality risk in adjusted HR. Specifically, FIB-4 ≥ 2.67 increased mortality by 78% (aHR:1.78, 95% CI: 1.06 – 3.00). Furthermore, FIB-4 ≥ 2.67 was significantly associated with a baseline aneurysm size ≥ 8cm (aOR: 2.67, 95% CI: 1.17 – 6.09). FIB-4 was independently associated with a higher mortality risk and higher aneurysm size. These findings suggest that FIB-4 assessment in clinical practice may enhance risk profiling, aiding in more precise stratification and management strategies for AAA patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Liver fibrosis, recognized as a hallmark of chronic liver disease, has garnered increasing attention due to its broader implications beyond hepatic health. Recent studies have shed light on its association with cardiovascular disease (CVD), suggesting a systemic impact that extends beyond the liver1,2,3,4,5. This expanding understanding underscores the importance of comprehensive risk assessment strategies for hepatic and cardiovascular health.

Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm (AAA) presents a significant health concern characterized by the progressive dilation of the abdominal aorta, often remaining asymptomatic until a catastrophic rupture occurs, leading to severe internal bleeding and high mortality rates6. AAA larger than 5 cm in females and 5.5 cm in males carry a significantly higher risk of rupture and are therefore recommended for elective repair7. Epidemiologically, AAA exhibits a distinct prevalence pattern, with a notable increase in incidence among individuals over 60, particularly males8,9,10,11. The morbidity and mortality associated with AAA underscore the importance of identifying prognostic markers to guide clinical management effectively.

Recent research has revealed a correlation between metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) and an increased risk of atherosclerosis12,13,14,15. This risk escalates proportionally with the severity of MASLD, particularly as fibrosis progresses16,17. Simultaneously, atherosclerosis emerges as a significant risk factor for the advancement of AAAs, thereby heightening the mortality risk among affected individuals18,19. Additionally, emerging evidence, such as the study conducted by Mohamid et al., highlights a heightened prevalence of MASLD in AAA patients and an increased risk of liver cirrhosis within this population20. This novel perspective underscores the need to thoroughly investigate the potential link between liver health and this insidious condition.

The FIB-4 index, initially designed for assessing liver fibrosis, has recently gained attention for its simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and reliance on routine clinical parameters21,22. Remarkably, this index has exhibited promise beyond its original purpose, suggesting a broader utility in evaluating vascular health and cardiovascular risk23. However, its potential as a predictor of AAA progression and mortality risk in AAA patients remains largely unexplored.

Hence, we designed this study to explore the clinical prognostic value of the FIB-4 index in patients with AAA. Specifically, we seek to determine whether the FIB-4 index is associated with increased mortality risk in AAA patients, identify its optimal cutoff value, and quantify its prognostic magnitude. Additionally, we investigate the relationship between the FIB-4 index and aneurysm size. By addressing these objectives, this study aspires to expand the utility of the FIB-4 index in risk stratification and surveillance of AAA patients, thereby informing both research arena and clinical practice.

Methods

Study design and data collection

This longitudinal, retrospective cohort study was conducted at Namazi Hospital, a prominent vascular surgery referral center in Shiraz, South Iran, from October 2016 to September 2021. The inclusion criteria included all patients who underwent open AAA repair following a preoperative diagnosis of AAA. Exclusion criteria were as follows: i) postoperative diagnosis other than AAA, ii) missing medical records, iii) missing data on AAA size, iv) incomplete laboratory results necessary for calculating the FIB-4 index and further adjustments, and v) no medical follow-up, as the last recorded contact with these patients occurred at the time of discharge. After applying these criteria, the final cohort consisted of 141 patients whose data were included in the analysis. A flowchart outlining the participant selection process is provided in Fig. 1. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences (SUMS).

Demographic and medical history data were collected from patient records and hospital databases. Key laboratory parameters required for calculating the FIB-4 index and adjusting subsequent models were retrieved from the Health Information System (HIS) of Namazi Hospital. These parameters included platelet count (× 103/µL), alanine transaminase (ALT, U/L), aspartate transaminase (AST, U/L), blood urea nitrogen (BUN, mg/dL), creatinine (mg/dL), blood sugar (mg/dL), and serum albumin (g/dL). Blood sugar and creatinine levels were obtained from admission laboratory tests, while AST, ALT, albumin, and platelet count were sourced from follow-up tests after patient stabilization.

FIB-4 index

The FIB-4 index is a validated noninvasive biomarker to assess liver fibrosis severity. It is computed using the following formula:

FIB-4 index = (Age × AST) / (Platelet Count × √ALT).

The FIB-4 index incorporates patient age and serum levels of AST, ALT, and Platelet Count to derive a numerical indicator of liver fibrosis severity, with higher index values indicative of more advanced fibrosis21.

Outcomes

The primary outcome of this study was all-cause mortality in the cohort, with mortality data obtained from patients’ post-surgical follow-up records. The secondary outcome was an AAA size ≥ 8 cm, with aneurysm diameters recorded from operation notes and cross-referenced with radiological findings for accuracy. The association between the FIB-4 index and mortality was assessed longitudinally, while its association with aneurysm size was evaluated cross-sectionally.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was conducted utilizing Python 3.11 programming language, harnessing an array of powerful libraries, including NumPy, Pandas, Scikit-learn (Sklearn), Statsmodels, Lifelines, and matplotlib.pyplot. Cox regression analysis was employed to explore the longitudinal association between the FIB-4 index and mortality. Logistic regression analysis was also utilized to evaluate the cross-sectional association between baseline characteristics and the FIB-4 index. Outcome measures were reported as hazard ratios with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) for Cox regression analysis, while odds ratios with 95% CI were reported for logistic regression analysis. Kaplan–Meier plots were utilized for survival analysis.

In preprocessing the data, given the skewed distribution of Blood Sugar (BS) and Creatinine (CR) levels, a logarithmic transformation was applied to these variables to achieve a more symmetrical distribution. The logarithmic transformation of BS and CR was performed using the natural logarithm (log base e), denoted as log (BS) and log (CR), respectively. This transformation effectively reduces the skewness of the data, making it more suitable for subsequent statistical analysis.

Furthermore, to ensure that all continuous variables were on a comparable scale and to mitigate the impact of potential outliers, standard scaling was applied. Standard scaling, also known as Z-score normalization, transforms the data with a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one. This process involves subtracting the mean of each variable from its value and then dividing by the variable’s standard deviation.

By standardizing the continuous variables, the coefficients obtained from the regression models can be directly compared, and the model’s performance is enhanced. These preprocessing steps were crucial in preparing the data for subsequent analysis, ensuring that the statistical models accurately captured the outcomes.

To assess the impact of the FIB-4 index on mortality, hazard ratios were calculated with a range of FIB-4 index cut-offs from 1.5 to 3.25, with 0.01 steps. Additionally, hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals were plotted for each cut-off of the FIB-4 index. This analysis was conducted at different adjustment levels to explore the robustness of the findings. Age, AST, ALT, and PLT were excluded from covariate adjustment, as they are inherent components of the FIB-4 index calculation.

Results

Baseline characteristics

A total of 141 patients (92% male), with a mean age of 70 years (SD: 11.5), were enrolled in the study and followed for a median duration of 35 months (IQR: 0.7 – 56.6). Throughout the follow-up period, 78 deaths occurred among the participants. Baseline characteristics of the patients are presented in Table 1.

Among the cohort, 82 patients (58.16%) were admitted due to ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAA), while 59 patients (41.84%) underwent elective AAA repair. Seventy-six patients were classified as high risk for liver fibrosis (FIB-4 ≥ 2.67). Furthermore, 57 patients presented with AAA sizes equal to or greater than 8cm. Hypertension was identified as the most prevalent comorbidity, affecting 60% of the patients.

Primary outcome

Unadjusted hazard ratios revealed a higher mortality risk among AAA patients across most FIB-4 cut-off values (Fig. 2). However, after adjustment for sex, HTN, DM, smoking status, opium use, BS, Cr, Alb, and AAA size ≥ 8cm, only the FIB-4 cut-off range of 2.58 – 2.74 remained significantly associated with mortality risk. Specifically, the hazard ratio for all-cause mortality in AAA patients with a baseline FIB-4 ≥ 2.67 was 1.78 (95% CI: 1.06 – 3.00). Kaplan Meier’s plot further illustrated AAA patients’ survival and hazard trends over time (Fig. 3).

illustrates the relationship between Fib-4 cut-off values and hazard ratios. The x-axis displays each Fib-4 cut-off value, while the y-axis represents the corresponding hazard ratio. Confidence intervals around each Fib-4 cut-off are depicted to provide a measure of uncertainty. The first plot depicts unadjusted hazard ratios, while the second plot presents fully adjusted hazard ratios.

Secondary outcome

Multivariable logistic regression analysis revealed a significant association between baseline FIB-4 levels exceeding 2.67 and the baseline size of AAA, even after adjusting for various covariates (Table 2). In fully adjusted logistic regression models, the odds ratio (OR) for AAA size ≥ 8 cm in patients with a FIB-4 level ≥ 2.67 was 2.67 (95% CI: 1.17 – 6.09).

Discussion

Main findings

In this longitudinal cohort study of 141 patients (92% male; mean age: 70 years) who underwent open AAA repair, 76 patients were classified as high risk for liver fibrosis (FIB-4 ≥ 2.67), and 57 patients presented with AAA ≥ 8 cm. During a median follow-up 35 months (IQR: 0.7–56.6), 78 deaths were recorded. A FIB-4 ≥ 2.67 was significantly associated with a larger aneurysm size (aOR: 2.67) and higher risk of mortality (aHR: 1.78), these findings underscore the potential clinical utility of the FIB-4 index in monitoring AAA patients, as it is linked to both increased mortality risk and larger aneurysm size.

Liver fibrosis and mortality risk in AAA patients

The analysis of unadjusted HR revealed a consistent trend of higher mortality risk among AAA patients across various FIB-4 index cut-off values, as shown in Fig. 2. However, after adjusting for several confounding variables, including sex, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, smoking status, opium use, blood sugar, creatinine, albumin, and AAA size ≥ 8cm, only a specific range of FIB-4 index cut-offs (2.58 – 2.74) remained significantly associated with mortality risk (Fig. 2). Specifically, a FIB-4 level ≥ 2.67 was linked to all-cause mortality (HR: 1.78, 95% CI: 1.06 – 3.00). Notably, previous studies have reported a similar association between a FIB-4 value ≥ 2.67 and cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk within the MASLD population24,25,26,27. For instance, Viera Barbosa et al. 27 found that over a median follow-up of 3 years, a FIB-4 ≥ 2.67 was the strongest predictor of major adverse cardiovascular events (adjusted HR: 1.80). Despite the diverse cut-offs for predicting advanced fibrosis in MASLD (optimal cut-off of 2.67) versus non-MASLD patients (optimal cut-off of 3.25)28, the similarity in predicting mortality between AAA and MASLD populations may suggest a shared risk profile between these two entities. These findings suggest that patients with AAA may also face an increased risk of MASLD, advanced fibrosis, and subsequent events associated with this risk.

Liver fibrosis and AAA size

Multivariable logistic regression analysis further elucidated the association between baseline Fib-4 levels and AAA size, revealing a significant correlation even after adjusting for various covariates. This discovery holds paramount clinical relevance, particularly when considering the alarming annual rupture risk associated with aneurysms ≥ 8cm, reported to be as high as 30–5029. These findings may elucidate why patients with more advanced fibrosis face a heightened risk of mortality. Furthermore, in addition to the bidirectional association between metabolic dysfunction and liver fibrosis30,31, the progression of fibrosis may exacerbate the likelihood of developing atherosclerosis16. These observations suggest a potential mechanistic link between liver fibrosis and higher AAA size, potentially mediated through the development of atherosclerosis. The presence of atherosclerotic plaques may contribute to the weakening and dilation of the abdominal aorta, ultimately leading to the enlargement of an AAA and an increased risk of rupture32,33.

Implications for clinical practice and future directions

The independent association observed in our adjusted analysis is not unique to patients undergoing open AAA repair. Previous studies have shown that liver fibrosis, as assessed by the FIB-4 index, is a prognostic marker for both all-cause mortality and cardiovascular outcomes across diverse populations34,35, suggesting that FIB-4 may serve as a surrogate marker for systemic vascular dysfunction. However, the optimal strategies for managing this high-risk group may vary depending on the clinical context.

In the context of AAA patients, our findings not only link liver fibrosis to increased mortality risk but also to larger aneurysm size. This highlights the potential utility of FIB-4 in identifying high-risk AAA patients who may benefit from closer surveillance. However, before incorporating FIB-4 into routine risk assessment and surveillance protocols for AAA patients, further research is needed to define its clinical implications. Specifically, studies are needed to determine whether FIB-4 is associated with AAA progression and whether it could be employed as a reliable tool for tracking disease progression over time.

Limitations and strengths

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting our study’s findings. First, the observational design of the study precludes us from establishing casualty. Second, the association between the FIB-4 index and aneurysm size was evaluated cross-sectionally, preventing us from assessing the impact of liver fibrosis on aneurysm progression over time. Thus, future longitudinal studies are needed to determine whether liver fibrosis contributes to aneurysm growth in the long term. it is important to acknowledge that additional variables not accounted for in our study may contribute to the observed association between FIB-4 levels and mortality risk. Lastly, the relatively modest sample size restricted our ability to perform sensitivity or subgroup analyses, limiting the generalizability of our findings. Therefore, validation in larger, multicenter cohorts is warranted to confirm and expand upon these results.

Despite limitations, our study stands out for several significant strengths. Initially, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to explore the association of liver fibrosis, as assessed by the FIB-4 index, with both mortality risk and aneurysm size in patients with AAA. This novel finding opens a new avenue for exploring the clinical relevance of FIB-4 in the context of AAA, potentially impacting risk assessment and management. Secondly, our study controlled for all available confounding factors in our statistical models. Notably, the strength of the association between FIB-4 levels and mortality remained significant even after this comprehensive adjustment, underscoring the robust, independent nature of this relationship. This adds a layer of validity and confidence to the observed correlation. Furthermore, our study introduces the concept of utilizing a non-invasive and cost-effective tool, the FIB-4 index, for risk stratification among AAA patients. This suggestion can potentially enhance the efficiency of risk assessment in a clinical setting, which can ultimately translate into more informed decision-making and improved patient care. Our research thus contributes to the ongoing effort to refine risk stratification and highlights the practical applicability of our findings in real-world clinical practice.

Conclusion

The findings of this study provide valuable insights into the prognostic factors affecting clinical outcomes in AAA patients undergoing repair surgery. Identifying the FIB-4 index as a potential predictor of mortality and higher AAA size underscores its utility as a non-invasive and readily accessible biomarker in clinical practice. However, further investigation is warranted to validate the observed association and establish an optimal cutoff for liver fibrosis. Specifically, more accurate fibrosis assessment methods, ideally through advanced imaging techniques, should be employed. Additionally, larger, multicenter studies are required to confirm generalizability and robustness of these associations across diverse cohorts. Future research should also explore whether liver fibrosis is linked to AAA progression over time. Such efforts are essential for refining risk stratification strategies and ultimately improving patient outcomes in the management of AAA.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

Ostovaneh, M. R. et al. Association of liver fibrosis with cardiovascular diseases in the general population: The multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA). Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging. 11(3), e007241 (2018).

Vilar-Gomez, E. et al. Fibrosis severity as a determinant of cause-specific mortality in patients with advanced nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A multi-national cohort study. Gastroenterology. 155(2), 443–457 (2018).

Henson, J. B. et al. Advanced fibrosis is associated with incident cardiovascular disease in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 51(7), 728–736 (2020).

Shili-Masmoudi, S. et al. Liver stiffness measurement predicts long-term survival and complications in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Liver Int. 40(3), 581–589 (2020).

Cardoso, C. R. L., Villela-Nogueira, C. A., Leite, N. C. & Salles, G. F. Prognostic impact of liver fibrosis and steatosis by transient elastography for cardiovascular and mortality outcomes in individuals with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and type 2 diabetes: the Rio de Janeiro Cohort Study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 20(1), 193 (2021).

Stather, P. W. et al. A review of current reporting of abdominal aortic aneurysm mortality and prevalence in the literature. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 47(3), 240–242 (2014).

Karthikesalingam, A. et al. Thresholds for abdominal aortic aneurysm repair in England and the United States. N. Engl. J. Med. 375(21), 2051–2059 (2016).

Singh, K., Bønaa, K. H., Jacobsen, B. K., Bjørk, L. & Solberg, S. Prevalence of and risk factors for abdominal aortic aneurysms in a population-based study : The Tromsø Study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 154(3), 236–244 (2001).

Ulug, P., Powell, J. T., Sweeting, M. J., Bown, M. J. & Thompson, S. G. Meta-analysis of the current prevalence of screen-detected abdominal aortic aneurysm in women. Br. J. Surg. 103(9), 1097–1104 (2016).

Grøndal, N., Søgaard, R. & Lindholt, J. S. Baseline prevalence of abdominal aortic aneurysm, peripheral arterial disease and hypertension in men aged 65–74 years from a population screening study (VIVA trial). Br. J. Surg. 102(8), 902–906 (2015).

Collin, J., Araujo, L., Walton, J. & Lindsell, D. Oxford screening programme for abdominal aortic aneurysm in men aged 65 to 74 years. Lancet. 2(8611), 613–615 (1988).

Cho, Y. K. et al. The impact of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and metabolic syndrome on the progression of coronary artery calcification. Sci. Rep. 8(1), 12004 (2018).

Kang, Y. M. et al. Fatty liver disease determines the progression of coronary artery calcification in a metabolically healthy obese population. PLoS One. 12(4), e0175762 (2017).

Kim, J. et al. Increased risk for development of coronary artery calcification in subjects with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and systemic inflammation. PLoS One. 12(7), e0180118 (2017).

Park, H. E. et al. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Is Associated With Coronary Artery Calcification Development: A Longitudinal Study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 101(8), 3134–3143 (2016).

Jamalinia, M., Zare, F. & Lankarani, K. B. Systematic review and meta-analysis: Association between liver fibrosis and subclinical atherosclerosis in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 58(4), 384–394 (2023).

Jamalinia, M., Zare, F., Noorizadeh, K. & Bagheri, L. K. Systematic review with meta-analysis: Steatosis severity and subclinical atherosclerosis in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 59(4), 445–458 (2024).

Cornuz, J., Sidoti Pinto, C., Tevaearai, H. & Egger, M. Risk factors for asymptomatic abdominal aortic aneurysm: systematic review and meta-analysis of population-based screening studies. Eur. J. Public Health. 14(4), 343–349 (2004).

Golledge, J., Muller, J., Daugherty, A. & Norman, P. Abdominal aortic aneurysm: pathogenesis and implications for management. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 26(12), 2605–2613 (2006).

Mahamid, M. et al. The interplay between abdominal aortic aneurysm, metabolic syndrome and fatty liver disease: a retrospective case-control study. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 12, 1743–1749 (2019).

Sterling, R. K. et al. Development of a simple noninvasive index to predict significant fibrosis in patients with HIV/HCV coinfection. Hepatology. 43(6), 1317–1325 (2006).

Mózes, F. E. et al. Diagnostic accuracy of non-invasive tests for advanced fibrosis in patients with NAFLD: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Gut. 71(5), 1006–1019 (2022).

Yi, M., Peng, W., Teng, F., Kong, Q. & Chen, Z. The role of noninvasive scoring systems for predicting cardiovascular disease risk in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 34(12), 1277–1284 (2022).

Akuta, N. et al. PNPLA3 genotype and fibrosis-4 index predict cardiovascular diseases of Japanese patients with histopathologically-confirmed NAFLD. BMC Gastroenterol. 21(1), 434 (2021).

Han, E. et al. Nonalcoholic fatty Liver Disease and sarcopenia are independently associated with Cardiovascular risk. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 115(4), 584–595 (2020).

Önnerhag, K., Hartman, H., Nilsson, P. M. & Lindgren, S. Non-invasive fibrosis scoring systems can predict future metabolic complications and overall mortality in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 54(3), 328–334 (2019).

Vieira Barbosa, J. et al. Fibrosis-4 Index Can Independently Predict Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 117(3), 453–461 (2022).

Sterling, R. K. et al. AASLD Practice Guideline on blood-based non-invasive liver disease assessments of hepatic fibrosis and steatosis. Hepatology. 81(1), 321–357. https://doi.org/10.1097/HEP.0000000000000845 (2024).

Brewster, D. C., Cronenwett, J. L., Hallett, J., W., Jr., Johnston, K. W., Krupski, W. C., Matsumura, J. S., Guidelines for the treatment of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Report of a subcommittee of the Joint Council of the American Association for Vascular Surgery and Society for Vascular Surgery. J Vasc Surg. 37(5):1106–17 2003.

Nakagami, H. Mechanisms underlying the bidirectional association between nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and hypertension. Hyperten. Res. 46(2), 539–541 (2023).

Li, Y. et al. Bidirectional association between nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and type 2 diabetes in Chinese population: Evidence from the Dongfeng-Tongji cohort study. PLoS One. 12(3), e0174291 (2017).

Kojima, K. et al. Aortic plaque distribution, and association between aortic plaque and atherosclerotic risk factors: An aortic angioscopy study. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 26(11), 997–1006 (2019).

Yao, L. et al. Association of carotid atherosclerosis and stiffness with abdominal aortic aneurysm: The atherosclerosis risk in communities (ARIC) study. Atherosclerosis. 270, 110–116 (2018).

Seo, Y. G., Polyzos, S. A., Park, K. H. & Mantzoros, C. S. Fibrosis-4 Index Predicts Long-Term All-Cause, Cardiovascular and Liver-Related Mortality in the Adult Korean Population. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 21(13), 3322–3335 (2023).

Anstee, Q. M. et al. Prognostic utility of Fibrosis-4 Index for risk of subsequent liver and cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality in individuals with obesity and /or type 2 diabetes: A longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Regional. Health Europe https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanepe.2023.100780 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We extend our heartfelt thanks to Ms. Zeynab Satiari Esmael Abadi, Head Nurse of the Vascular Surgery Ward, for her assistance in the process of data gathering.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MJ and SAM conceptualized and designed the study. SAM, MR, and AH contributed to data acquisition. MJ conducted the statistical analysis. MJ and MR performed data visualization. MJ and SAM drafted the manuscript, and KBL provided critical revisions. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript. MJ and SAM contributed equally and shared co-first authorship.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the ethics committee of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences under reference number IR.SUMS.MED.REC.1402.446 adhered to the ethical standards outlined by institutional and national research committees, following the principles of the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its subsequent amendments or equivalent ethical standards. Prior to enrollment, all participants provided written informed consent.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. The purpose of the research was thoroughly explained to the patients, and they were assured that their information would be kept confidential by the researcher.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jamalinia, M., Mirhosseini, S.A., Ranjbar, M. et al. Association of liver fibrosis with aneurysm size and mortality risk in patients undergoing open abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. Sci Rep 15, 3301 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88133-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88133-x