Abstract

Strabismus, or eye misalignment, is a common condition affecting individuals of all ages. Early detection and accurate classification are essential for proper treatment and avoiding long-term complications. This research presents a new deep-learning-based approach for automatically identifying and classifying strabismus from facial images. The proposed methodology leverages Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) to achieve high accuracy in both binary (strabismus vs. normal) and multi-class (eight-class deviation angle for esotropia and exotropia) classification tasks. The dataset for binary classification consisted of 4,257 facial images, including 1,599 normal cases and 2,658 strabismus cases, while the multi-class classification involved 480 strabismic and 142 non-strabismic images. These images were labeled based on ophthalmologist measurements using the Alternate Prism Cover Test (APCT) or the Modified Krimsky Test (MK). Five-fold cross-validation was employed, and performance was evaluated using sensitivity, accuracy, F1-score, and recall metrics. The proposed deep learning model achieved an accuracy of 86.38% for binary classification and 92.7% for multi-class classification. These results demonstrate the potential of our approach to assist healthcare professionals in early strabismus detection and treatment planning, ultimately improving patient outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Strabismus is defined as the misalignment of the eyes when looking at an object1. It is commonly considered a visual impairment mostly affecting children with a prevalence ranging from 0.14–5.65%2, and approximately 2–5% of individuals in general population3. Horizontal strabismus, including esotropia and exotropia, is the most common type. Strabismus is the primary cause of amblyopia and reduced visual function, as well as a significant contributor to decreased binocular vision, greatly affecting the quality of life of preschool children. Prompt establishment of binocular alignment can enhance long-term vision and sensorimotor results4,5,6. manual measurement of ocular deviaton can be time-consuming and relies on the professional’s expertise and the patients commitment to cooperate. On the other hand, there is a scarcity of pediatric ophthalmologists who are able to accurately evaluate strabismic children. The alternate prism cover test (APCT) is considered the most accurate method for the angle of deviations, although it is time-consuming and has an interexaminer variance of 5 to 10 prism diopters (PD)7. Alternative approaches, such as the Hirschberg and Krimsky tests, result in far more variable results even when conducted by skilled strabismologists. Choi et al. found that even professionals in strabismus underestimated or overestimated by a minimum of 10 prism diopters when using the Hirschberg and Krimsky tests8. Artificial intelligence (AI) has slowly transformed healthcare in the past few years. AI, a field of computer science, seeks to develop intelligent machines capable of tasks similar to human-like visual perception and speech recognition. Recent advancements in AI and deep learning have led to significant development in diagnostic technology, providing valuable insights into eye diseases such as cataract, glaucoma, and diabetic retinopathy9,10,11,12. The deep learning system automatically identifies visual patterns by utilizing representation-learning techniques with several layers of conceptualization, eliminating the requirement for human feature engineering by training on extensive datasets of labeled pictures. The impressive performance of Deep Learning (DL) in detecting ocular diseases from various types of images like slit lamp photography and ultra-widefield fundus images indicates a significant opportunity for DL to offer a dependable resource to assist in diagnosing, assessing, and planning surgeries for strabismus13,14. Karaaslan et al. explored using deep learning and image processing to automatically perform the Hirschberg test for strabismus detection. Their algorithm achieved an accuracy of 90% or higher for both eyes in measuring the degree of strabismus in 88 patients. While a slight margin of error existed due to the 2D nature of the images, the results suggest this approach could potentially be used for broader strabismus screening15. Considering the significant global prevalence of strabismus, it is crucial to accurately detect and assess the condition, especially in cases where patients may be uncooperative or when the necessary tools or expertise are lacking. Therefore, this paper introduces deep learning methods designed to detect referable horizontal strabismus in primary gaze photos captured during a clinical evaluation. The performance of the deep learning model was assessed by testing the algorithms on an external dataset. Recognizing this potential, our study presents a novel approach for automated strabismus detection and classification using deep learning analysis of facial images. The primary contribution of this study is the development of a deep learning-based model for the identification and categorization of strabismus. This approach offers a scalable and objective alternative that has the potential to enhance the accuracy and accessibility of diagnostics. The objective of this investigation is to create an automated system for the classification of strabismus into two categories: normal and strabismus. Furthermore, the system assesses the extent of misalignment and classifies it according to prism diopter measurements, thereby enabling a multi-class classification framework. The proposed methodology is designed to address the limitations of traditional diagnostic methods, including their reliance on specialized knowledge and the time-consuming nature of their procedures, by leveraging advancements in deep learning.

Method of data collection

The study followed the guidelines of the Helsinki Declaration and received approval from the Tehran University of Medical Sciences Institutional Review Board for the use of anonymized images (IR.TUMS.RARABIH.REC.1401.032). The dataset for multi-class classification of eye deviation angles was collected using a specific protocol. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects or their legal guardians for participation in the current study. Also, informed consent was obtained from all subjects or their legal guardians for publication of images in an online open-access publication.

Imaging distance

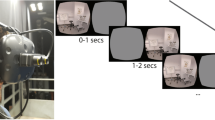

Since the target distance, which refers to the distance between the camera with the fixation target and the patient, can impact the amount of deviation, this study determined the optimum imaging distance to be between 35 and 50 cm. Previous studies and data collection methods (such as camera, virtual reality headset, smartphone, eye tracker, etc.) have reported an optical imaging distance ranging from 35 cm to one meter14,16,17,18,19,20.

Stability of subject’s position in front of the camera

To ensure improved image results, it is important for the subject’s head to be positioned straight towards the camera. A chin-rest was utilized to maintain the stability of the subject’s head.

Definition of the target

During the data collection process, Subjects focused on the white Canon logo on the camera, ensuring corneal reflexes in both eyes. All participants received strabismic ocular evaluation including the alternate prism-cover test (APCT) conducted by an experienced pediatric ophthalmologist (M.S), which served as the gold standard for the type and angle of horizontal strabismus (esotropia or exotropia). APCT was the benchmark for assessing ocular misalignment. The patients are first categorized in esotropia and exotropia, and then in four measurement groups. The multi-class categorization method classified eye deviation ranges into four groups (0–20 PD, 20–40 PD, 40–60 PD, and 60> ), each with two types (esotropia or exotropia), resulting in eight classes (classes 0–3 for exotropia and 4–7 for esotropia). Full-face photographs were taken using a Canon EOS 7D Mark II camera. Every photo has a set resolution of 5472 × 3648 pixels. Images were gathered from participants with and without strabismus across all age and gender groups. 480 subjects with strabismus and 142 individuals without strabismus were recruited. For accurate deviation assessment, a camera-to-subject setup was determined based on previous published studies including cameras, VR headsets, and other devices. Subject positioning was maintained using a chin rest that allowed for steady head placement, with the option to alter the height for youngsters. A graded tape in millimeters (served as a scale) attached over the forehead rest made accurate image analysis possible. .

The collected data were labeled and underwent a review and cleaning process, during which mistakes were corrected and low-quality or inaccurate photos were eliminated. Photos taken during the COVID-19 epidemic while wearing masks were not used because they interfered with facial identification. Only individuals who had a direct gaze toward the target were included, and deviations were assessed according to their gaze direction (Fig. 1).

Participants with both vertical and horizontal abnormalities were excluded from the study. The images were preprocessed to serve as input for training the neural network, which aimed to identify horizontal eye misalignment and measure the degree of strabismus. Face detection is the initial and crucial stage in any facial processing system. Face recognition aims to recognize all facial components inside a picture, irrespective of varying ambient factors and facial appearances. However, challenges in face recognition can result in decreased accuracy and speed. Initially, to identify eye deviation, it is crucial to ascertain the eyes’ location and extract these regions utilizing a reliable and accurate method. Dlib was utilized in this study to identify and isolate the ocular regions. Dlib is a library that enables the utilization of computer vision and machine learning methodologies. Although Dlib is primarily based on C++, it is compatible with other languages such as Python. Face landmark detection, a solution built using the Dlib library, was employed21. An input image of a whole face is processed to generate an array of facial characteristics ranging from 1 to 68. The coordinates of indexes 37 to 46 in this array are utilized to extract the eye region (Figs. 2 and 3).

Sixty-eight facial landmark detectors that have been previously trained using the iBUG 300-W dataset. Each numeral symbolizes a specific facial feature. To extract the eye area, index numbers from 37 to 48 are considered22.

Most computer vision systems tend to perform better with a higher volume of data. However, acquiring additional data can often be challenging and costly. To address this limitation, data augmentation techniques were employed to enhance efficiency and achieve a balanced distribution of data across different classes. Specifically, the augmentation methods included shifting, changing brightness levels, and adding Gaussian noise to artificially expand the dataset. These techniques not only increased the volume of data but also introduced variability, enabling the model to generalize better across different scenarios. As shown in Table 1, ocular deviation was classified into eight ranges based on the degree of eye deviation.

The evaluation metrics of the models are as follows: Recall = TP / (TP + FN), Precision = TP / (TP + FP), and F1 = (2 × TP) / (2 × (TP + FP + FN)). Precision is a metric used to evaluate the accuracy of a model’s positive predictions. It is calculated by dividing the number of true positives (correct positive predictions) by the sum of true positives and false positives (incorrect positive predictions). In simpler terms, precision reflects how often the model is correct when it predicts a positive outcome23. “Sensitivity” (also called recall or the true positive rate) refers to a test’s ability to correctly identify individuals with strabismus as positive. The “F1score(F-measure)” is a suitable criterion for evaluating the accuracy of the test because it considers both precision and recall together. This criterion is one in the best case and zero in the worst case24.

Development of the algorithm

Binary and multi-class classification

Two datasets, one containing normal data and the other containing strabismus data, are utilized for classification. There are a total of 4257 data sets, consisting of 1599 normal photos and 2658 strabismus images (for binary classification) and 480 strabismic and 142 normal (for multi-class classification) labeled based on ophthalmologist diagnosis. In this research, we utilized a fully connected (FC) layer as the main classifier to translate the extracted features into output classes. The FC layer, a fundamental component of neural network architectures, is characterized by its dense connections, where every neuron in one layer links to all neurons in the subsequent layer. This architecture allows for complex representations of the data, enabling the model to effectively learn intricate patterns and relationships within the dataset25. Additionally, ResNet101 network was employed for the purpose of two-class and multi-class classification, utilizing skip connections (also known as shortcut connections) to mitigate the vanishing gradient problem and facilitate the training of very deep networks. On the other hand, ResNet101 is well-suited for both two-class and multi-class classification tasks due to its ability to preserve feature information across layers and maintain efficient gradient flow. These skip connections allow the model to learn deeper representations, leading to enhanced classification accuracy and robustness. We also tested different parameter settings, including learning rates, batch sizes, and optimization algorithms, to guarantee optimal performance26.

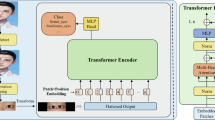

The proposed method’s flowchart is shown in Fig. 4. The backbone architecture of ResNet is used for feature extraction, followed by the utilization of the global average pooling layer to transform the output into a vector. A hidden dense layer (fully connected) with 128 neurons and the hyperbolic tangent activation function was applied, along with a dropout of 0.5 probability for regularization. The final layer is a dense output layer with 2 neurons for binary classification or 8 neurons for multi-class classification, utilizing the Softmax activation function. The model employed the categorical cross-entropy loss function, which combines Softmax activation with Cross-Entropy loss, for classification. The adaptive momentum (ADAM) optimizer was utilized with an initial learning rate of 0.001, and the model was trained with 200 epochs. The network takes as input the eye region with dimensions of 300 × 75 × 3. After extracting features, the data is fed into the global average pooling (GAP) block for classification. In the final layer of the network, two neurons are used for binary classification, while eight neurons are used for multi-class classification, depending on the application.

The network structure of ResNet for binary or multi-class classifications is as follows: the ocular regions are provided to the ResNet backbone to extract appropriate features. Depending on the categorization type (binary or multi-class), the last layer of the network consists of either two or eight neurons.

Results

Following the data pre-processing steps outlined in the Methodology section, the dataset containing 4,257 images was randomly split into training and testing sets at an 80/20 ratio. The ResNet101 deep learning (DL) model was employed for binary classification, aiming to distinguish between individuals with and without strabismus based on facial image analysis.

As shown in Table 2, the model achieved an overall accuracy of 86.38%, demonstrating its ability to correctly classify individuals into the two defined categories. Additionally, the model exhibited a balanced performance across various evaluation metrics, including F1-score: 0.8639, Recall: 0.8638 (Sensitivity), and Precision: 0.8641. These results suggest that the model can effectively distinguish between individuals with and without strabismus based on facial image analysis, achieving a high degree of accuracy and demonstrating a good balance between precision and sensitivity in identifying positive cases.

The performance of the binary classification model is depicted in Fig. 5. The confusion matrix provides valuable insights into the accuracy of our model in correctly classifying strabismus and normal cases.

Resnet deep learning model was also used for multi-class classification to categorize strabismus into eight classes using facial image analysis. The classifications presumably correspond to four class of exotropia and four class of esotropia, ranging from 0 to 20 prism diopters to greater than 60 prism diopters.

The evaluation criteria for multi-class classification using the DL model achieved a precision of 89.51%, an F1-score of 91.08%, and an accuracy of 92.7%, as indicated in Table 3.

Considering Fig. 6, the predicted correct diagnosis for class one (the deviation between 20 and 40) and four (the deviation between 0 and 20 PD) are 73% and 86%, which is the lowest rate of correct diagnosis compared to other classes. When the degree of eye deviation is minimal (less than 30 prism diopters), even the measurement of the strabismus angle in clinical examinations varies by a maximum of ten prism diopters. Therefore, detecting eye deviation in minor deviations becomes challenging. In such cases, within class 1, 18% of individuals with deviations ranging from 20 to 40 were mistakenly categorized into class 0 (0 to 20 prism diopters). actually, no additional data augmentation (shifts, brightness changes, or noise addition) has been applied to the class one data. Also, classes three, six, five and seven demonstrate a network performance of over 90% accuracy, indicating strong performance of the ResNet model in deviations exceeding 50 prism diopters.

The confusion matrix of the ResNet101 network for eight-class classification. The horizontal axis indicates the predicted class by the network, and the vertical axis indicates the true class of the strabismus images. Classes zero to three represent images with exotropia, while classes four to seven represent images with esotropia.

Discussion

Early identification and precise categorization of strabismus are critical for initiating appropriate treatment and avoiding long-term consequences such as amblyopia (lazy eye) and abnormal binocular vision development. The standard method of strabismus diagnosis relies on ophthalmologists’ direct evaluations using techniques such as the cover test and prism cover test (PCT). These methods need expert hands and cooperation of the patients, and so are subjected to inter-examiner variability, as well as hardships in examining non-cooperative patients and smaller children in particular. This underscores the need for objective, automated, and user-friendly methods for screening of strabismus and categorization4,5,6.This study investigates the potential of deep learning approaches to meet this crucial demand. We introduced a novel technique that uses convolutional neural networks (CNNs) to scan face photos and automatically detect and categorize strabismus. Our results are encouraging, with the model reaching an accuracy of 86.38% for binary classification (strabismus vs. normal) and 92.7% for multi-class classification. These findings demonstrate the potential of our deep learning architecture for strabismus diagnosis. The accuracy of our model in both binary and multi-class classification tasks demonstrates its effectiveness in diagnosing strabismus and distinguishing between various severities and types. This feature is particularly useful in situations where access to specialized ophthalmological expertise or standard diagnostic equipment is limited. For instance, the model can be integrated into telemedicine platforms or mobile applications, enabling preliminary strabismus screening in remote areas or resource- constrained settings. Moreover, the ability to distinguish between exotropia and esotropia, two major types of strabismus with distinct treatment methods, might enhance the therapeutic value of this method by guiding appropriate treatment selections. Furthermore, the model’s precision of 89.51% demonstrates its capacity to reduce false-positive detections, which can be critical in avoiding needless referrals and diagnostic procedures. This feature is especially significant given the possible psychological and emotional strain associated with misdiagnosis and needless therapies, particularly in children. It is vital to recognize the limitations of this study. First, the study used a retrospective dataset obtained from a single center, which may have introduced selection bias and limited the findings’ generalizability.

Recent studies have employed various deep learning techniques for strabismus detection and classification. For instance, Lixia Lou et al.27, Jiewei Lu et al.28, Jaehan Joo et al.29 and Ce Zheng et al.14 used neural networks to extract the eye region in their works, taking advantage of the high-level feature-learning capabilities possessed by these models. On the other hand, this study uses Dlib for extracting the eye region because it is easy to use, fast, and requires fewer computations. While Neural networks have improved accuracy and robustness in dealing with variability; Dlib provides a quick and lightweight substitute that does not require significant training and datasets, making it appropriate for resource-constrained applications. Jaehan Joo et al.29 suggested a generative model-based data augmentation technique to overcome the challenges of severe data scarcity in designing a deep learning-based automatic strabismus detection system. They used a generative model based on StyleGAN2-ADA to develop the system and evaluated the strabismus classification performance using two classifiers. ResNet-50 with 85.71% accuracy and ResNeXt101 with 87.75% accuracy, without data augmentation (using 900 images of normal eyes and 896 images of strabismic eyes). In contrast, the binary classification task in the current study was not augmented with data, and our model attained an accuracy of 86.38%. Further validation on a broader and more varied population across various institutions is required to determine the model’s generalizability and resilience in real-world clinical settings. Second, while the model achieved great accuracy, it is crucial to note that it is not designed to replace the experience of ophthalmologists. Instead, it is envisioned as a complementary tool to help with early identification and informed clinical decision-making. In addition, ethical issues related to data security and privacy as well as any biases in the training set need to be properly taken into account while developing and deploying a model. In summary, this study reveals another fascinating possibility for automated strabismus identification and classification employing facial photo analysis through deep learning-based algorithms. The model demonstrated exceptional performance in binary and multi-class classification tasks, accurately identifying strabismus and distinguishing between distinct categories and degrees of severity. Additional study and development are required to overcome the stated limitations and ensure the beneficial and responsible application of this technology in clinical practice. Finally, the effective incorporation of such deep learning models has the potential to transform strabismus diagnosis by enabling early identification, improved treatment planning, and ultimately, better patient outcomes.

In Table 4, we conducted a comparative literature review and analysis of numerous studies that employed deep learning to detect and classify strabismus. In addition to the diverse datasets employed for training and validation objectives, the comparative analysis in Table 4 provides a comprehensive overview of the methodologies employed, ranging from CNNs to more complex architectures.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the application of deep learning in detecting and classifying eye deviation disorder, specifically strabismus, has shown tremendous promise in revolutionizing the field of ophthalmology. We have achieved impressively precise binary classification by using whole face image analysis to identify if a person has an eye abnormality or is healthy.

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Yang Meng, D. H., Xu, Y. X. Y., Xiao, D., Chen, C. &, Assessment of retinal and choroidal microcirculation after unilateral recession-resection surgery for horizontal strabismus by swept-source optical coherence tomography angiography. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-46670-3 (2023).

Agaje, B. G. et al. Strabismus prevalence and associated factors among pediatric patients in southern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. J. Int. Med. Res. https://doi.org/10.1177/0300060520964339 (2020).

Koc, F., Ozal, H., Yasar, H. & Firat, E. Resolution in partially accommodative esotropia during occlusion treatment for amblyopia. J. Am. Assoc. Pediatr. Ophthalmol. Strabismus 11, 211–212 (2007).

Friedman, D. S. et al. Prevalence of amblyopia and strabismus in white and African American children aged 6 through 71 months: The Baltimore pediatric eye disease study. Ophthalmology 115, 2128–2134 (2009).

McKean-Cowdin, R. et al. Prevalence of amblyopia or strabismus in asian and non-Hispanic white preschool children. Ophthalmology 120(10), 2117–2124 (2013).

Wallace, D. K. et al. Esotropia and Exotropia preferred practice pattern®. Ophthalmology 125(1), P143–P183 (2018).

de Jongh, E., Leach, C., Tjon-Fo-Sang, M. J. & Bjerre, A. Inter-examiner variability and agreement of the alternate prism cover test (APCT) measurements of strabismus performed by 4 examiners. Strabismus 22(4), 158–166 (2014).

Choi, R. Y. & Kushner, B. J. The accuracy of experienced strabismologists using the Hirschberg and Krimsky tests. Ophthalmology 105(7), 1301–1306 (1998).

Topol, E. J. High-performance medicine: the convergence of human and artificial intelligence. Nat. Med. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-018-0300-7 (2019).

Ting, D. S. W. et al. Artificial intelligence and deep learning in ophthalmology. Br. J. Ophthalmol. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjophthalmol-2018-313173 (2019).

Abràmoff, M. D., Lavin, P. T., Birch, M., Shah, N. & Folk, J. C. Pivotal trial of an autonomous AI-based diagnostic system for detection of diabetic retinopathy in primary care offices. npj Digit. Med. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-018-0040-6 (2018).

Tekkeşin, A. İ. Artificial intelligence in healthcare: Past, present and future. Anatol. J. Cardiol. https://doi.org/10.14744/AnatolJCardiol.2019.28661 (2019).

Mao, K. et al. An artificial intelligence platform for the diagnosis and surgical planning of strabismus using corneal light-reflection photos. Ann. Transl. Med. https://doi.org/10.21037/atm-20-5442 (2021).

Zheng, C. et al. Detection of referable horizontal strabismus in children’s primary gaze photographs using deep learning. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1167/tvst.10.1.33 (2021).

Karaaslan, Ş & Kobat, S. G. A new method based on deep learning and image processing for detection of strabismus with the Hirschberg test. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 44, 103805 (2023).

Valente, A. A. et al. Application of virtual reality for the treatment of Strabismus and Amblyopia. In: IEEE 6th International Conference on Serious Games and Applications for Health (SeGAH) https://doi.org/10.1109/SeGAH.2018.8401357. (2018).

Yeh, P. H., Liu, C. H., Sun, M. H., Chi, S. C. & Hwang, Y. S. To measure the amount of ocular deviation in strabismus patients with an eye-tracking virtual reality headset. BMC Ophthalmol. 185, 246 (2021).

Miao, Y., Jeon, J. Y., Park, G., Park, S. W. & Heo, H. Virtual reality-based measurement of ocular deviation in strabismus. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 185, 105132 (2020).

Zenghai Chen, Z. C., Fu, H. & Lo, W. L. Strabismus recognition using eye-tracking data and convolutional neural networks. J. Healthc. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/7692198 (2018).

Bakker, N. M. et al. Accurate gaze direction measurements with free head movement for strabismus angle estimation. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 60(3028), 3035 (2013).

King, D. E. Dlib-ml: A machine learning toolkit. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 10, 1755–1758 (2009).

Amato, G., Falchi, F., Gennaro, C. & Vairo, C. A Comparison of Face Verification with Facial Landmarks and Deep Features. (2018).

Menditto, A., Patriarca, M. & Magnusson, B. Understanding the meaning of accuracy, trueness and precision. Accred. Qual. Assur. 12, 45–47 (2007).

Trevethan, R. Sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values: foundations, pliabilities, and pitfalls in research and practice. Front. Public Health 5, 307 (2017).

Kalaycı, T. A. & Asan, U. Improving classification performance of fully connected layers by fuzzy clustering in transformed feature space. Symmetry 14, 658 (2022).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1512.03385 (2015).

Lou, L. et al. Automated photographic analysis of inferior oblique overaction based on deep learning. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 13, 329–338 (2023).

Lu, J. et al. Automated strabismus detection for telemedicine applications. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1809.02940 (2018).

Joo, J. et al. Enhancing automated strabismus classification with limited data: Data augmentation using StyleGAN2-ADA. Plos one https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0303355 (2024).

Zheng, C. et al. Automated detection of steps in videos of strabismus surgery using deep learning. BMC Ophthalmol. 24, 242 (2024).

Wu, D. et al. An artificial intelligence platform for the screening and managing of strabismus. Eye 38, 3101–3107 (2024).

Jabbar, A. et al. A retinal detachment based strabismus detection through FEDCNN. Sci. Rep. 14, 1–22 (2024).

Amin, R., Ahmed, A., Hasan, S. S. U. & Akbar, H. Multiple eye disease detection using deep learning. Found. Univ. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 3(2), 14–26 (2022).

Kang, Y. C., Yang, H. K., Kim, Y. J., Hwang, J.-M. & Kim, K. G. Automated mathematical algorithm for quantitative measurement of strabismus based on photographs of nine cardinal gaze positions. Biomed. Res. Int. 2022, 9840494 (2022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.Y. and H.A. contributed to the conceptualization, methodology, software implementation, data curation, and formal analysis. M.S. and M.R.A. provided clinical expertise, data collection, and validation. E.K.P. supervised the project and contributed to the interpretation of results. All authors contributed to the writing and review of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The local ethics committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences approved the study in accordance with Helsinki’s ethical principles (IR.TUMS.RARABIH.REC.1401.032).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yarkheir, M., Sadeghi, M., Azarnoush, H. et al. Automated strabismus detection and classification using deep learning analysis of facial images. Sci Rep 15, 3910 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88154-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88154-6