Abstract

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a complex gynecological endocrinological condition that significantly impacts women’s fertility during their reproductive lifespan. The causes of PCOS are multifaceted, and its pathogenesis is not yet clear. This study established a rat model of PCOS and, in conjunction with clinical samples and database data, analysed the role of claudin 11 (CLDN11) in follicular granulosa cells (GCs) in regulating the proliferation of GCs. Our findings revealed a notable decrease in the protein expression of CLDN11 within the follicular GCs of individuals with PCOS. In vitro rat cell experiments revealed that interference with CLDN11 significantly inhibited viability and increased the apoptosis of GCs. Additional research has illuminated the mechanism by which CLDN11 regulates the expression levels of CCND1 and PCNA through the PI3K/AKT signalling pathway, significantly influencing the proliferation of rat follicular GCs. Furthermore, overexpression of CLDN11 via an adeno-associated virus (AAV) vector was found to reverse the PCOS-like phenotype induced in rats by letrozole. Our findings suggest that CLDN11 stimulates the proliferation of these cells by activating the PI3K/AKT pathway, thereby increasing the expression of CCND1 and PCNA. These discoveries underscore the critical function of CLDN11 in regulating the functionality of follicular GCs, which offers novel insights into the fundamental mechanisms governing PCOS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is the most prevalent reproductive endocrine disorder among women of childbearing age and often leads to infertility, with a prevalence rate of approximately 5 − 10%1. The clinical manifestations exhibited by female patients with PCOS are heterogeneous and include anovulation, menstrual disorders, hyperandrogenism, ovarian ultrasound showing polycystic follicles, and infertility2. The 2003 Rotterdam criteria state that having two or more of the three criteria of hyperandrogenism, oligo-ovulation/anovulation, and polycystic ovaries, excluding other diseases that cause hyperandrogenism, can be diagnosed as PCOS3,4. PCOS patients have many antral follicles but no dominant follicle development, and many follicles undergo atresia, which is the pathological and physiological basis for infertility5. PCOS transcends the realm of merely a reproductive system disorder, extending its impact beyond gynecology and obstetrics to encompass various vital systems throughout the body. It significantly elevates the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus, obesity, endometrial cancer, and cardiovascular disease, thereby posing a grave threat to women’s overall physical and mental well-being6,7. The emergence of PCOS often involves a complex interplay of multiple factors, including genetics, environmental influences, inflammation, and dysfunctions in the neuroendocrine and immune systems. This results in ovarian impairment, irregular follicular development, and ovulation disturbances8. However, the precise molecular mechanisms contributing to the onset of PCOS remain largely elusive, and clinical practice faces a scarcity of effective therapeutic approaches to address abnormal follicular development in patients afflicted with this syndrome9.

A significant feature of PCOS is the appearance of polycystic ovaries, with the accumulation of preantral and antral follicles exceeding 2–3 times that of normal ovaries10. Interdependence between the oocyte and its surrounding GCs has been demonstrated in the oocyte development11. Follicular GCs serve as somatic cells that envelop the oocyte within the follicle, fostering a conducive microenvironment for its development, such as nutrients and growth regulators, and their levels of proliferation and apoptosis play crucial roles in the normal development of the follicle12. In PCOS-related abnormal follicles, the proliferation level of GCs is weakened, indicating that the compromised proliferation capacity of GCs has been implicated in the aberrant development of follicles associated with PCOS13. Jiang et al. reported the upregulation of ANGPTL4 expression in both the serum and GCs of patients with PCOS, where the excessive expression of ANGPTL4 impedes the progression of the cell cycle from the G1 to S phase, subsequently inhibiting the proliferation of GCs14. Hence, the dysfunctional proliferation of GCs represents a pivotal factor in the underlying etiology of PCOS15. Delving into the molecular mechanisms that govern abnormal GC proliferation in PCOS patients can uncover key insights into the pathogenesis of this disorder.

Claudin 11 (CLDN11) is a tight junction protein with multiple functions. It not only forms a cross-cell barrier and regulates the transport of biomolecules but also participates in cell-cell adhesion and regulates cell proliferation and death16,17. Research has shown that changes in CLDN11 expression levels and disruption of tight junction structures may indicate tumor formation, cell migration, and increased invasiveness18,19. CLDN11 is also closely related to obesity, insulin resistance, and the inflammatory response20. Investigations have revealed a link between irregular CLDN11 expression and stimulation of the PI3K/AKT signalling pathway21, a complex network intricately involved in orchestrating various cellular physiological processes, particularly cell proliferation22,23. While these findings underscore the importance of CLDN11 in modulating cell proliferation, the specific expression pattern of CLDN11 in ovarian tissue and its contribution to the development of PCOS remains elusive24,25. Our study presents the first evidence of downregulation of CLDN11 in individuals with PCOS by collecting clinical samples of GCs from PCOS patients and further confirmed that CLDN11 is associated with poor development of follicular GCs and ovarian dysfunction in a rat model. In vitro experimental findings further revealed that by interacting with the PI3K/AKT signalling pathway, CLDN11 influences the expression of CCND1 and PCNA, thereby regulating the proliferation of follicular GCs. These novel findings shed light on the intricate mechanisms underlying PCOS and lay the groundwork for formulating innovative therapeutic approaches to address this condition.

Results

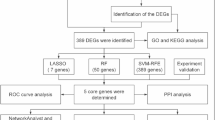

Lowered CLDN11 levels were correlated with the clinical manifestations of PCOS

Using the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database, we analyzed CLDN11 expression patterns in healthy control groups and patients diagnosed with PCOS. By acquiring the raw data from GSE155489 and employing R language tools, we meticulously screened for differentially expressed genes (DEGs). Our findings, presented through volcano plots and heatmaps, unequivocally demonstrated marked disparities in the gene expression landscapes of human GCs between the PCOS and healthy groups (Fig. 1A and B). Notably, these DEGs were intimately tied to cell proliferation and apoptosis mechanisms, involving pivotal pathways such as the PI3K/AKT, Hippo, and PPAR signalling pathways (Fig. 1C). Further interrogation of the GSE155489 dataset revealed a marked reduction in CLDN11 expression, specifically within the follicular GCs of PCOS patients, in stark contrast to their healthy counterparts (Fig. 1B and D). To validate these findings, we procured clinical samples and directly assessed CLDN11 protein levels, confirming the significant downregulation of CLDN11 in the follicular GCs of PCOS patients (Fig. 1E). To explore the clinical implications of these findings, we conducted a Pearson correlation analysis, with the relative expression of CLDN11 mRNA in follicular GCs as the dependent variable and pivotal clinical indicators as independent variables. Our results revealed a positive correlation between CLDN11 mRNA expression and markers such as AMH, T, and LH/FSH, suggesting a tight link between CLDN11 expression in follicular GCs and the clinical phenotype of PCOS (Fig. 1F). We subsequently assessed the diagnostic potential of CLDN11 in PCOS through receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis, which yielded an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.803, a sensitivity of 56.7%, and a specificity of 96.7% (Fig. 1G), underscoring its robustness in predicting PCOS occurrence. In summary, our study underscores the potential significance of CLDN11 in modulating the pathological processes of PCOS and emphasizes its potential as a diagnostic biomarker for this condition.

CLDN11 was reduced in the GCs of PCOS patients and has diagnostic value for PCOS. (A) Volcanic map of DEGs between the GSE155489 control group and PCOS patients. (B) Heatmap of DEGs between the GSE155489 control group and PCOS patients. (C) DEGs from GSE155489 were subjected to the KEGG enrichment analysis. (D) Assessment of CLDN11 mRNA abundance in the GSE155489 control group and PCOS patients. (E) Western blot assessment (a) with accompanying quantification analysis (b) of CLDN11 in the follicular GCs of clinical patients. (F) Pearson correlation analysis investigated the relationships between CLDN11 expression and clinical characteristics. (G) ROC curve analysis of the diagnostic value of CLDN11 for PCOS. GCs, granulosa cells; DEGs: differentially expressed genes; KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; BMI: body mass index; AMH: antimüllerian hormone; FSH: follicular stimulating hormone; T: testosterone; LH: luteinizing hormone; ROC: receiver operating characteristic.

CLDN11 was downregulated in the follicular GCs of a PCOS rat model established with letrozole

To decipher the role of CLDN11 in the etiology of PCOS, we devised a rat model by administering letrozole for 23 consecutive days. Our findings demonstrated that beginning on the 12th day, we observed a pronounced increase in weight gain in the model group (LET) compared with the control group (Fig. 2A-a and A-b). Notably, the two groups had no discernible differences in insulin sensitivity, as assessed by intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test (IPGTT) (Fig. 2B) or insulin tolerance test (ITT) (Fig. 2C). Given that menstrual irregularity was a defining characteristic of PCOS, we examined the estrous cycles of the rats and observed a marked disruption in the LET group, with the rats remaining in interphase (Fig. 2D). Histopathological analysis of the ovaries further revealed the presence of multiple cystic follicles and a reduction in the number of corpora lutea, indicative of PCOS-like changes (Fig. 2E and F). Additionally, there was a significant elevation in the serum levels of T and LH and the LH/FSH ratio in the LET group (Fig. 2G), confirming the successful induction of a PCOS model. To explore the function of CLDN11 within this framework, we analysed its expression levels within follicular GCs via Western blotting. Our results revealed a marked decrease in CLDN11 protein levels in the GCs of LET rats compared with those in the control group (Fig. 2H). We performed immunohistochemical staining to confirm this observation visually and ascertain the localization of CLDN11 within ovarian tissue. This analysis revealed that CLDN11 was robustly expressed in the GCs of the control group, whereas its levels were markedly diminished in the GCs of the LET rats (Fig. 2I). These collective observations point to a crucial role of CLDN11 in modulating the pathological processes of PCOS, with its downregulation potentially contributing to the onset of this condition.

A PCOS rat model was established through the letrozole-induced methodology. (A) Body weight (a) and weight gain (b) of rats in the LET group and control group (n = 10). (B) IPGTT: Evaluating an individual’s glucose tolerance (n = 10). (C) ITT was used to evaluate insulin resistance (n = 10). (D) Representative vaginal smears of the estrus cycle (a) and estrus status (b) of rats in the LET and control groups (n = 10), including the nucleated epithelial cells (★), keratinized epithelial cells (⇨), and leukocytes (▲). (Scale bar, 100 μm). (E) Comparison of the typical histological characteristics of rat ovaries between the control group (a) and the LET group (b), including the corpus luteum (▲), follicles with cystic expansion (⇨), and sinus follicles (★). Fewer corpus luteum and more cystic follicles were observed in animals in the LET group. (Scale bar, 200 μm). (F) Cystic expanded follicles (a) and corpus luteum (b) in rat ovarian tissue (n = 3). (G) ELISA was used to measure the concentrations of hormones in the serum of the two groups of rats (n = 7). (H) Western blot assessment (a with accompanying quantification analysis (b) of CLDN11 in follicular GCs. (I) Representative image (a, b) of IHC showing the expression of CLDN11 in ovarian GCs, CLDN11 was robustly expressed in the GCs of the control group, whereas its levels were markedly diminished in the GCs of the LET rats (c). (Scale bar, 200 μm). LET: letrozole; IPGTT: Intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test; ITT: insulin tolerance test; T: testosterone; E2: estrogen; LH: luteinizing hormone; FSH: follicular stimulating hormone; GCs, granulosa cells; IHC: immunohistochemical.

In vitro experiments have demonstrated that the absence of CLDN11 results in the inhibition of GC proliferation and the enhancement of GC apoptosis

To determine the influence of CLDN11 deficiency on follicular GCs, we isolated GCs from rats and established a CLDN11-knockdown model (Si CLDN11) via small interfering RNA (siRNA). This discovery paved the way for us to investigate the intricate regulatory mechanisms employed by CLDN11 in modulating GC proliferation and apoptosis. Follicle-stimulating hormone receptor (FSHR) immunofluorescence analysis revealed robust fluorescence signals indicative of high-purity follicular GCs suitable for further experimentation (Fig. 3A). Following CLDN11 interference in these cells, RT‒qPCR and Western blotting revealed notable downregulation of CLDN11 at both the mRNA and protein levels in the Si CLDN11 group compared with the control group (Fig. 3B and C). To assess the functional consequences of this downregulation, we performed Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) and EdU assays, which revealed reduced cell viability and proliferation in the Si CLDN11 group compared with the control group (Fig. 3D and E). Furthermore, flow cytometry analysis showed a notable increase in the percentage of apoptotic cells in the Si CLDN11 group (Fig. 3F). We also detected proteins related to steroid hormone synthesis and found that compared with the control group, the protein expression of CYP17A1 and HSD3B1 in the Si CLDN11 group GC was significantly increased (Fig. S1, Supporting Information). These results demonstrate that CLDN11 deficiency impairs GC proliferation and promotes GC apoptosis.

Influence of CLDN11 on proliferation and apoptotic processes in rat follicular GCs. (A) GCs were identified by analyzing FSHR immunofluorescence results (scale bar, 100 μm). (B) The expression of CLDN11 was assessed via RT‒qPCR (n = 3). (C) The relative protein expression of CLDN11 was assessed via western blotting (n = 3). (D A CCK8 assay was used to assess the influence of CLDN11 on the activity of GCs (n = 10). (E) Assessment of the impact of CLDN11 on the proliferative capacity of GCs through EdU analysis. (F) Flow cytometry analysis was conducted to examine the effect of CLDN11 on the progression of cellular apoptosis (n = 3). GCs, granulosa cells.

Transcriptomic profile of GCs following CLDN11 knockdown

To explore the molecular underpinnings of CLDN11 regulation of follicular GC proliferation and apoptosis, we employed RNA-seq to compare the transcriptomes of control and Si CLDN11 GC samples. Our analysis confirmed intragroup homogeneity among the samples (Fig. 4A) and revealed 981 DEGs, with 694 downregulated and 287 upregulated genes in the Si CLDN11 group compared with those in the control group (Fig. 4B). A heatmap of the top 100 DEGs between groups was presented in Fig. 4C. Gene Ontology (GO) analysis revealed the prevalence of DEGs associated with cell proliferation and apoptosis-related categories (Fig. 4D), which aligns with the findings of the clinical database. Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis revealed marked enrichment of DEGs within the PI3K/AKT signalling pathway (Fig. 4E). qPCR validation confirmed alterations in key PI3K/AKT pathway genes (JAK2, CSF3, ITGB1, CCND1, PCNA, and EREG) identified through RNA-seq (Fig. 4F). Notably, the proliferation-associated genes CCND1 and PCNA were significantly downregulated at both the transcriptional and translational levels (Fig. 4G and H), with CCND1 being a pivotal regulator of the G1-to-S phase transition. Flow cytometry analysis corroborated these findings, revealing decreased S-phase cells upon CLDN11 knockdown (Fig. 4I). Moreover, following the CLDN11 knockdown, there was notable downregulation of the antiapoptotic gene BCL2 and upregulation of the apoptotic genes BAX and CASPASE-3 at both the mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 4J and K). These results underscore the profound impact of CLDN11 knockdown on the transcriptional landscape of rat follicular GCs and its pivotal role in modulating GC proliferation and apoptosis.

Transcriptome sequencing. (A) Pearson correlation coefficient plot (a) and PCA plot (b). (B) A comparative analysis of mRNA alterations between the control and Si CLDN11 groups (a) and a depiction of DEGs through a volcano plot (b). (C) A heatmap displaying the expression of DEGs. (D) DEGs were subjected to GO enrichment analysis. (E) DEGs were subjected to KEGG enrichment analysis. (F) The genes’ expression in the PI3K/AKT signalling pathway was assessed via RT‒qPCR (JAK2, CSF3, ITGB1, CCND1, PCNA, and EREG; n = 3). (G) The expression of proliferation-related genes was assessed via RT‒qPCR (n = 3). (H) Western blot assessment (a) and accompanying quantification analysis (b) of proliferation-related proteins (n = 3). (I Flow cytometry analysis was conducted to examine the effect of CLDN11 on the progression of the cell cycle (n = 3). (J) mRNA expression levels of genes associated with apoptosis were evaluated via RT‒qPCR (n = 3). (K) Western blotting (a) and quantification (b) analyses of apoptosis-related proteins (n = 3). DEGs: differentially expressed genes; GO: Gene Ontology; KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes.

CLDN11 deficiency inhibits GC proliferation by suppressing the activation of the PI3K/AKT signalling pathway

Notably, the PI3K/AKT signalling pathway has emerged as a prominent player among the signalling pathway involved and was widely acknowledged for its essential function in controlling cellular proliferation and apoptosis. We found that Si CLDN11 significantly inhibited P-AKT/AKT (Fig. 5A). Consistent with these findings, the LET group presented a notable reduction in the P-AKT/AKT ratio (Fig. 5B). We employed SC79, a well-established activator of the PI3K/AKT signalling pathway. We cotreated ovarian GCs with Si CLDN11 and SC79 and detected the P-AKT/AKT ratio in the control, Si CLDN11, SC79, and Si CLDN11 + SC79 groups. The Si CLDN11 group presented a marked decrease in the P-AKT/AKT ratio, whereas the SC79 group presented a significant increase. Notably, in the Si CLDN11 + SC79 group, the inhibitory effects of CLDN11 on P-AKT/AKT were significantly reversed, and SC79 did not affect the expression level of CLDN11 (Fig. 5C). Further analysis revealed that, compared with the control group, the Si CLDN11 group presented pronounced decreases in cell viability and proliferation; however, these effects were reversed in the Si CLDN11 + SC79 group (Fig. 5D and E). Flow cytometry data revealed a substantial reduction in the proportion of S-phase cells in the Si CLDN11 group. In contrast, this proportion notably increased in the Si CLDN11 + SC79 group, thereby facilitating the progression of GCs from the G1 phase to the S phase (Fig. 5F). The Si CLDN11 + SC79 group presented significantly elevated expression of both CCDN1 and PCNA at both the mRNA and protein levels. The suppression of CCND1 and PCNA expression, both transcriptionally and translationally, induced by CLDN11 deficiency was efficiently mitigated through the administration of SC79. No statistically significant difference was detected between the Si CLDN11 + SC79 and the control groups (Fig. 5G and H). These observations indicate that a deficiency in CLDN11 impedes the PI3K/AKT signalling pathway, resulting in decreased expression of CCND1 and PCNA, which subsequently arrests the proliferation of GCs.

The proliferation of GCs was modulated by CLDN11 via the PI3K/AKT signalling pathway. (A) Western blot assessment (a) with accompanying quantification analysis (b) of AKT and P-AKT in the control group and the Si CLDN11 group (n = 3). (B) Western blot assessment (a) with accompanying quantification analysis (b) of AKT and P-AKT in both the control group and LET group (n = 3). (C) Western blot assessment (a) with accompanying quantification analysis (b) of AKT and P-AKT in the control, Si CLDN11, SC79, and Si CLDN11 + SC79 groups (n = 3). (D) CCK8 was used to detect cell viability (n = 10). (E) EdU was used to quantify cellular proliferation (scale bar, 100 μm). (F) Flow cytometry analysis was employed to quantify the fractions of cells residing in the cell cycle (a) overall progression and specifically within the S phase (b) (n = 3). (G) mRNA expression levels were confirmed through RT‒qPCR analysis of CCND1 and PCNA (n = 3). (H) Western blot assessment (a) with accompanying quantification analysis (b) of CLDN11, CCND1, and PCNA (n = 3). GCs, granulosa cells; LET: letrozole.

Overexpression of CLDN11 in the ovary improved the PCOS phenotype induced by letrozole in rats

To uncover the functional implications of CLDN11 in PCOS, an in vivo study in which an adeno-associated virus was used to overexpress CLDN11 in PCOS rats through in situ ovarian injection was conducted (Fig. 6A). Frozen sections and Western blotting of ovarian tissue revealed successful overexpression of CLDN11 adeno-associated virus (AAV) (Fig. 6B and C). The immunohistochemistry results showed that the PCOS + AAV-CLDN11 group presented increased expression of CLDN11 in GCs (Fig. 6D). Furthermore, our findings indicated that the rats in the PCOS + AAV-CLDN11 group experienced weight gain comparable to that observed in the standard group (Fig. 6E). The results of the IPGTTs and ITTs revealed that neither the PCOS group nor the PCOS + AAV-CLDN11 group presented impaired glucose and insulin tolerance (Fig. S2, S3, Supporting Information). Compared with those in the control group, both the PCOS group and the PCOS + AAV-NC group presented irregular estrous cycles, whereas the rats in the PCOS + AAV-CLDN11 group presented normalized estrous cycles (Fig. 6F). Further examination of serum hormone levels in PCOS rats revealed a marked elevation in T, LH, and the LH/FSH ratio in both the PCOS and PCOS + AAV-NC groups, as opposed to the control group, whereas PCOS + AAV-CLDN11 reversed this increase (Fig. 6G). Pathology of tissue sections revealed that PCOS + AAV-CLDN11 significantly improved the degree of polycystic ovarian morphology in ovaries induced by letrozole. Follicles at different developmental stages were observed, and the GCs were arranged in multiple layers and tightly packed. A clear corpus luteum was visible on the ovary (Fig. 6H). The morphology of the polycystic ovaries was relieved, with a decrease in the number of follicles with cystic dilation and an increase in the number of corpora lutea (Fig. 6I). We observed pronounced upregulation of CLDN11, specifically in the ovarian tissue of the PCOS + AAV-CLDN11 group compared with that in the PCOS + AAV-NC group, and no statistically significant alterations in CLDN11 expression were detected in the uterus, lungs, kidneys, or brain tissues between these two groups (Fig. 6J). The proliferation and apoptosis rates of GCs serve as crucial indicators for predicting follicle outcomes, and these processes were intimately linked to follicular atresia. Notably, the phosphorylated AKT level was more significant in the PCOS + AAV-CLDN11 group than in both the PCOS and PCOS + AAV-NC groups (Fig. 6K). Our findings indicated that the expression of genes associated with GC proliferation, namely, CCND1 and PCNA, was suppressed in both the PCOS and PCOS + AAV-NC groups. Conversely, in the PCOS + AAV-CLDN11 group, these proliferation-related genes were upregulated (Fig. 6L and M). Compared with the control group, the rate of TUNEL-positive cells in the ovarian tissue of the PCOS group was significantly increased. Compared with the PCOS group, the rate of TUNEL-positive cells in the ovarian tissue of the PCOS + AAV- CLDN11 group was significantly decreased (Fig. S4, Supporting Information). These findings suggest that CLDN11 promotes follicular GC proliferation and reverses the polycystic ovarian morphology phenotype induced by letrozole in rats by activating the PI3K/AKT signalling pathway.

CLDN11 improved the PCOS phenotype induced by letrozole in rats. (A) Flowchart of the AAV treatment experimental design for PCOS rats. (B) Fluorescence image of frozen sections of ovarian tissue (scale bar, 500 μm), green fluorescence shows successful overexpression of AAV in ovarian. (C) Analyses of ovarian tissue via Western blotting (a) and quantification (b) (n = 3). (D) Illustrative image depicting the extent of CLDN11 expression in the ovary via IHC staining (a) (scale bar, 500 μm), increased expression of CLDN11 in ovaries of PCOS + AVA-CLDN11 group (b). (E) Changes in the body weights of CLDN11 rats (a) and increases in the body weights of rats (b) (n = 5), *, Control vs. PCOS; &, PCOS + AAV-NC vs. PCOS + AAV-CLDN11; #, PCOS vs. PCOS + AAV-CLDN11; (F) Estrous cycle (n = 5). (G) ELISA analysis of serum T, LH, E2, FSH, and LH/FSH in rats (n = 5). (H Effects of CLDN11 overexpression on the morphology of rat ovarian tissue, including the corpus luteum (▲), follicles with cystic expansion (⇨), and sinus follicles (★), many corpus luteum and fewer cystic follicles were observed in the PCOS + AAV-CLDN11 group. (scale bar, 200 μm). (I) Cystic expanded follicles (a) and corpus luteum (b) in rat ovarian tissue (n = 3). (J) Relative abundance of CLDN11 expression in major tissues and organs (n = 3). (K) Western blot assessment (a) and accompanying quantification analysis (b) of CLDN11, AKT, and P-AKT in rat ovaries (n = 3). (L) Gene expression levels of mRNAs related to proliferation and apoptotic processes in rat ovaries (n = 3). (M) Western blot assessment (a) and accompanying quantification analysis (b) of proliferation- and apoptosis-related genes in rat ovaries (n = 3). IPGTT: Intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test; ITT: insulin tolerance test; AAV: adeno-associated virus; IHC: immunohistochemical; T: testosterone; E2: estrogen; LH: luteinizing hormone; FSH: follicular stimulating hormone.

Discussion

PCOS, a complex and enigmatic disorder with an undefined cause, is the prevalent reproductive endocrine malfunction among women of reproductive age. It significantly contributes to female infertility due to ovulation disturbances, menstrual irregularities, and increased androgen levels26,27. GCs play a pivotal role in establishing a favourable microenvironment that is crucial for the progression of follicular development and the maturation of oocytes. Research has shown that the primary underlying factor contributing to ovulation dysfunction in individuals with PCOS is aberrant follicular development28. Notably, irregular proliferation or apoptosis of GCs is a pivotal factor that significantly influences the abnormal follicular development observed in patients with PCOS29. The homeostasis between GC proliferation and apoptosis is vital, as it can affect the growth, fertilization, early embryonic development, and even pregnancy outcomes of oocytes by influencing their living environment30. By leveraging the GEO database and thorough clinical sample analysis, this research revealed a noteworthy decrease in the expression levels of CLDN11 in the GCs of follicular tissues from patients with PCOS. In vitro cellular experiments further revealed that this deficiency in CLDN11 expression hindered the transition of GCs from the G1 to S phase of the cell cycle, effectively suppressing their proliferative capacity. Significantly, restoring CLDN11 levels through AAV-mediated overexpression in PCOS-like model rats effectively reversed these effects. These findings underscore the pivotal role of CLDN11 in modulating GC proliferation and follicular development.

CLDN11 is a gene responsible for encoding a protein that belongs to the claudin family31. Claudins are integral components of membrane proteins that form a vital part of tight junction strands, which function as selective barriers to prevent unregulated movement of solutes and water across the paracellular spaces between epithelial or endothelial cell layers. These tight junctions are essential for preserving cell polarity and facilitating signal transduction processes32. Notably, the protein encoded by CLDN11 functions as a fundamental building block of myelin in the central nervous system, where it assumes a pivotal role in modulating the proliferation and migratory processes of oligodendrocytes, which are essential for myelin production and maintenance33. The transcriptome results of this study revealed that when CLDN11 was knocked down at the cellular level in vitro, the DEGs were significantly enriched in gene entries such as “cell junction,” “extracellular space,” “positive regulation of gene expression,” “signalling receptor activity,” and signalling pathways such as “PI3K/AKT,” “calcium signalling pathway,” and “cell adhesion molecules.” Consistent with this, CLDN11 is closely related to pathways and functions such as “cell junction”34, “positive regulation of gene expression,” “PI3K/AKT”35, and “cell adhesion molecules”36. The PI3K/AKT signalling pathway plays a pivotal role in governing the proliferation and apoptosis of GCs during follicular development in both humans and rats37. This study revealed the significant regulatory function of CLDN11 in modulating GC proliferation. The results indicated that the downregulation of CLDN11 significantly upregulated the expression of genes associated with the proliferation-regulating PI3K/AKT signalling pathway. Further investigation revealed that CLDN11 deficiency hindered GC proliferation by inhibiting the activation of the PI3K/AKT signalling pathway. Importantly, PI3K/AKT pathway activators significantly reversed the cell proliferation inhibition caused by CLDN11 deficiency.

The PI3K/AKT signalling pathway plays a pivotal role in regulating the proliferation of GCs38. Plumbagin has been shown to impede GC proliferation and enhance apoptosis in PCOS patients by inhibiting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway39. Moreover, studies suggest that USP25 modulates this pathway by mediating PTEN deubiquitination, which affects GC proliferation and apoptosis, contributing to the development of PCOS40. Additionally, FGF21 has been shown to stimulate estradiol production and proliferation in porcine GCs via the PI3K/AKT signalling pathway41. In this study, the flow cytometry findings demonstrated a marked reduction in the proportion of S-phase cells after the knockdown of CLDN11. Consistent with these findings, the transcriptome results revealed that knockdown of CLDN11 notably diminished the expression of CCND1, a protein known to facilitate the transition from the G1 phase to the S phase of the cell cycle, in GCs42. These findings suggest that CLDN11 modulates the expression of CCND1 and PCNA via the PI3K/AKT signalling pathway, thereby influencing the proliferation of follicular GCs.Finally, treatment of PCOS-like rats overexpressing CLDN11 via the AAV vector revealed that letrozole-induced PCOS-like rats with impaired estrus, abnormal ovarian morphology, increased androgens, metabolic disorders, and ovarian dysfunction were ameliorated after CLDN11 was overexpressed by AAV (Fig. 6). In summary, this study underscores the pivotal regulatory role of CLDN11 in the etiology and progression of PCOS. Our findings revealed that a deficiency or absence of CLDN11 impedes the activation of the PI3K/AKT signalling pathway, resulting in the downregulation of CCND1 and PCNA expression. Consequently, this impedes the transition of cells from the G1 phase to the S phase and impairs GC proliferation. These discoveries offer fresh perspectives on the underlying mechanisms of PCOS and propose promising avenues for preventative and therapeutic interventions. Nevertheless, it is imperative to recognize the constraints and limitations inherent in this study, notably its partial reliance on rat models. To gain a comprehensive understanding of the molecular mechanisms driving PCOS pathogenesis, additional research utilizing clinical samples and integrating data from extensive clinical cohorts is imperative, particularly through the lens of multiomics studies.

Materials and methods

Clinical samples

mRNA sequencing profiles and their associated clinical information from PCOS patients and healthy control subjects were obtained from the publicly accessible GEO database. Between 2023 and 2024, a total of 30 participants diagnosed with PCOS and an equal number of healthy individuals serving as controls were recruited for the study, all of whom underwent in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer (IVF-ET) procedures at the Reproductive Medicine Center of the Second Hospital of Jilin University. The PCOS group was selected based on the Rotterdam criteria. In contrast, the control group included individuals with tubal infertility or male factor infertility. Clinical data and ovarian GC samples were collected from each participant. The clinical parameters recorded included age, body mass index (BMI), duration of infertility, levels of follicular stimulating hormone (FSH), luteinizing hormone (LH), LH/FSH ratio, estrogen (E2), progesterone (P), prolactin (PRL), testosterone (T), thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), and antimüllerian hormone (AMH); antral follicle count (AFC); metaphase II (MII) oocyte rates; fertility outcomes; and clinical pregnancy rates. All patients, including the control women and those with PCOS, underwent fasting elbow venous blood drawing at 8:00 AM on the 2nd to 4th day of their natural menstrual cycles. These details were summarized in Table 1. The research strictly adhered to the ethical principles outlined in the Helsinki Declaration. Before participation, all individuals involved provided written informed consent. The study has obtained informed consent from all participants and/or their legal guardians. The study’s protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee affiliated with the Second Hospital of Jilin University.

PCOS rat model

Twenty SPF/SD rats (Liaoning Changsheng Biotechnology Co., Ltd., China) aged 70 days and weighing approximately 250 g were randomly assigned to two equal-sized groups, a control group and a letrozole (LET) group, with ten rats in each group. In the control group, an equivalent physiological saline was orally gavaged for 23 consecutive days. In the LET group, letrozole, sourced from Zhejiang Haizheng Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. in China, was dissolved in physiological saline (1 mg/kg/d) and administered via oral gavage for 23 consecutive days. The rats were weighed every 3 days, and weight changes were monitored. During the last 10 days of modelling, the estrus status of the two groups of rats was recorded by observing vaginal smears at the same time every day to verify the successful induction of the PCOS model. We conducted live animal studies following the ARRIVE guidelines. We strictly adhere to the American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) Guidelines for the Euthanasia of Animals (2020) as a comprehensive resource for guidance on veterinary best practices for the anesthesia and euthanasia of animals. All experimental protocols were additionally authorized by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Jilin University, operating under license number SY202405002.

AAV rescue model

AAV (supplied by Shenyang Mingsheng Biotechnology Co., Ltd., China) was administered following the manufacturer’s instructions to achieve CLDN11 overexpression. The rats were randomly allocated into four groups, with five rats in each group: the control group (equal volume of physiological saline), the PCOS group (letrozole solution, 1 mg/kg/d), and the PCOS + AAV-NC group, which consisted of PCOS rats that were inoculated with a negative control AAV, whereas the PCOS + AAV-CLDN11 group included PCOS rats that were infected with an AAV vector designed for CLDN11 overexpression. The PCOS modelling method was performed as described earlier. On the 7th day of PCOS modelling, 5 × 1011 (v.g./ovary) NC or CLDN11-overexpressing AAV was injected in situ into the rat ovaries, and the remaining rats were subjected to sham surgery42. After the 23rd day of model establishment, the estrus status of the rats was recorded by observing vaginal smears at the same time every day to validate the successful induction of the PCOS model. Five weeks after AAV administration, when the estrus cycle was in the same stage, the ovaries and plasma of the rats were harvested for histological examination and molecular biology analyses.

IPGTT and ITT

For the IPGTT, the rats were fasted for 16 h before the test. Subsequently, glucose (2 g/kg), dissolved in physiological saline, was administered via intraperitoneal injection. Blood samples were obtained from the tail vein at various time points postinjection (0, 15, 30, 60, 90, and 120 min), and blood glucose concentrations were determined via an Accu Chek glucose meter supplied by Roche Diagnostics Corp.

In the ITT experiment, the rats were fasted for 4 h. After administering an intraperitoneal insulin injection at 0.75 IU/kg, blood samples were collected from the tail vein at 0-, 15-, 30-, 45-, and 60-minute intervals. These samples were subsequently analysed for blood glucose concentrations via an Accu Chek glucose meter produced by Roche Diagnostics Corp.

Serum hormone measurement

Under tribromoethanol anesthesia, blood samples were extracted from the abdominal aorta of the rats. The collected blood was allowed to sit at ambient temperature (25 °C) for 30 min, followed by centrifugation at 4500 × g for 15 min. The resulting serum samples were frozen and stored at -80 °C until further analysis. The rat serum’s LH, FSH, T, and E2 levels were quantitatively determined via an ELISA kit (Eli Lilly & Biotech Co., Ltd., Wuhan, China).

Morphology and immunohistochemistry

The ovarian tissue samples were preserved in 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 24 to 48 h for fixation, followed by paraffin embedding. For histological analysis, multiple consecutive 5 μm thick sections were cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE). Once the samples were adequately sealed and dried, they were examined under a microscope to assess their morphology and identify follicles and corpus luteum by cell type, structure, pattern, and orientation43.

For immunohistochemical staining, the sections were subjected to antigen retrieval by immersion in 0.01 M sodium citrate solution at 95 °C for 10 min. Next, the samples were blocked with BDT solution for 30 min to prevent nonspecific binding. The source and dilution of the antibody were as follows: CLDN11 (Solarbio, K002574P, 1:800).

Cell culture and processing

Clinical sample: GCs were isolated from follicular fluid aspirated from the ovaries of women undergoing IVF-ET. In brief, the follicular fluid was washed with PBS and then purified by density gradient centrifugation using Ficoll to obtain the precipitate. After another wash with PBS, the cellular precipitate was collected, resuspended, and plated in culture dishes in DMEM/F12 (Sigma–Aldrich, USA) supplemented with 10% FBS (ABW, Uruguay). The cells were then incubated in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C.

Rat GC: The culture of GCs from rats was characterized as described previously39. SFP/SD female rats (Liaoning Changsheng Biotechnology Co., Ltd., China) weighing approximately 50 g at 3 weeks of age were adaptively fed for 2 days and euthanized via the cervical dislocation method, exposed the bilateral ovaries of the rats and flushed with PBS. GCs were extracted from the follicles of the rats. The GCs were maintained in culture in DMEM/F12 medium (Sigma Aldrich, USA). Once the GCs reached 70% confluence, they were treated with 50 nM Si CLDN11 (Shenyang Ming Sheng Biotechnology Co., Ltd., China). The cells were also exposed to an AKT activator, SC79 (Med Chem Express). The medium was exchanged and replenished for 24 h before the subsequent experimental procedures.

Identification of GCs

Identification of isolated GCs via FSHR immunofluorescence. Upon reaching 50–70% confluence in a 6-well plate, the GCs were subjected to three sequential washes with PBS, each lasting 5 min. Fix the cells in methanol at 4 °C for 20 min. Incubate the cells with 5% goat serum for 30 min. Incubate the cells with a 1:200 dilution of rabbit anti-rat FSHR primary antibody (RRID: AB_2636411) at 4 °C overnight. Then, add FITC-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG (RRID: AB_2923335) to the cells and incubate them in the dark for 2 h. Finally, stain the cells with 10 µg/mL propidium iodide dye and incubate them in the dark for 15 min. Images of the stained cells were captured via a fluorescence microscope produced by Olympus, located in Tokyo, Japan.

Cell viability assay

Cell viability was quantitatively evaluated via the CCK-8 assay, sourced from Med Chem Express (Monmouth Junction, NJ, USA). Rat GCs were seeded into a 96-well plate, ensuring each well contained 100 µL of culture medium. The designated experimental treatments were subsequently administered to the cells for 24 h. Under subdued lighting, 10 µL of CCK-8 solution was dispensed into each well, and the plates were then incubated in the dark for 3 to 5 h, depending on the cell density. The absorbance was subsequently measured at a wavelength of 450 nm via a microplate reader from BioTek (Winooski, VT, USA).

5-Ethynyl-2’-deoxyuridine (EdU) staining

An EdU (5-ethynyl-2’-deoxyuridine) incorporation assay, sourced from RiboBio (Guangzhou, China), was utilized to assess cell proliferation. The experimental protocol adhered strictly to the manufacturer’s instructions provided by RiboBio.

TUNEL assay

Firstly, dewax the paraffin sections until they were hydrated. Next, a protease K working solution was applied to cover the tissue and incubate it in a warm box. After centrifuging the sections to remove excess liquid, add a permeabilization working solution to cover the tissue and incubate at room temperature. Once again, centrifuge the sections to dry them, then apply a buffer to cover the tissue. Add the reaction mixture and incubate in a 37 °C incubator for 2 h. Counterstain the nuclei with DAPI and incubate in the dark at room temperature for 10 min. Finally, the sections were mounted using an antifade mounting medium.

Flow cytometry analysis

Cell cycle kinetics: After 24 h of treatment with Si CLDN11, SC79, or Si CLDN11 + SC79, the GCs were collected and transferred to a 1.5 mL centrifuge tube. Afterwards, the cells were fixed in 70% ethanol at 4 °C for 12 h. The GCs were subsequently stained following the staining protocol provided by Beyotime Biotechnology. The dynamics of the cell cycle were subsequently analysed via a BD LSR flow cytometry system produced by BD Biosciences (Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). Flow cytometry was used with a membrane-associated protein V-FITC apoptosis detection kit from Beyotime (C1062L) to evaluate the cell apoptosis rate.

RNA extraction Library Construction and sequencing

Total RNA was extracted via TRIzol reagent supplied by Invitrogen. StringTie and edgeR were employed to evaluate gene expression at the transcriptional level. Significant differences in mRNA expression were identified via the R package.

Quantitative real-time PCR

According to the manufacturer’s instructions, total RNA was isolated from tissues with TRIzol reagent (Takara, Japan). The specific primer sequences employed in this study were detailed in Table 2.

Western blotting analysis and quantification

A consistent amount of protein (ranging from 10 to 20 µg) was utilized per the standardized protocol. The antibody dilutions used were as follows: CLDN11 (Solarbio, K002574P, 1:800), CCND1 (Bioworld, BS9827M, 1:800), PCNA (Bioworld, BS6438, 1:800), BCL-2 (Bioworld, BS65629, 1:800), BAX (Bioworld, BS90121, 1:800), CASPASE-3 (Bioworld, BS9865M, 1:800), p-AKT (Bioworld, BS40319, 1:800), AKT (Bioworld, AP0378, 1:800), p-PI3K (MCE, HY-P81211, 1:800), PI3K (Bioworld, MB9419, 1:800), and GAPDH (Bioworld, MB001, 1:8000). An enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) kit from Beyotime Biotechnology (China) was used to detect the immune response.

Statistical analysis

The data were analysed and graphically represented via Prism 8 software (GraphPad). For comparisons between two groups, two-tailed Student’s t-tests were employed, whereas one-way ANOVA was used for multiple group comparisons. The statistical details of each experiment were detailed in the respective Fig. legends, including the n values. The results were expressed as the mean ± SEM and were derived from three independent experimental replicates. Statistical significance was established at P < 0.05, indicated by “*,” and a higher level of statistical significance was set at P < 0.01, denoted by “**.”

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Fauser, B. C. J. M. et al. Consensus on women’s health aspects of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): the Amsterdam ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored 3rd PCOS Consensus Workshop Group. Fertil. Steril. 97, 28–U84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.09.024 (2012).

Dumesic, D. A. et al. Scientific Statement on the Diagnostic Criteria, Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, and Molecular Genetics of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Endocr. Rev. 36, 487–525. https://doi.org/10.1210/er.2015-1018 (2015).

Chang, J. et al. Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil. Steril. 81, 19–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2003.10.004 (2004).

Fauser, B. et al. Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Hum. Reprod. 19, 41–47. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/deh098 (2004).

Kaltsas, A. et al. The Silent Threat to Women’s Fertility: Uncovering the Devastating Effects of Oxidative Stress. Antioxidants 12 https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox12081490 (2023).

Millan-de-Meer, M., Luque-Ramirez, M., Nattero-Chavez, L. & Escobar-Morreale, H. F. PCOS during the menopausal transition and after menopause: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum. Reprod. Update. 29, 741–772. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmad015 (2023).

Choudhury, A. A. & Rajeswari, V. D. Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) increases the risk of subsequent gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM): a novel therapeutic perspective. Life Sci. 310 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2022.121069 (2022).

Vatier, C. & Christin-Maitre, S. Epigenetic/circadian clocks and PCOS. Hum. Reprod. 39, 1167–1175. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/deae066 (2024).

Walters, K. A., Bertoldo, M. J. & Handelsman, D. J. Evidence from animal models on the pathogenesis of PCOS. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 32, 271–281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beem.2018.03.008 (2018).

Dapas, M. & Dunaif, A. Deconstructing a syndrome: genomic insights into PCOS causal mechanisms and classification. Endocr. Rev. 43, 927–965. https://doi.org/10.1210/endrev/bnac001 (2022).

Uyar, A., Torrealday, S. & Seli, E. Cumulus and granulosa cell markers of oocyte and embryo quality. Fertil. Steril. 99, 979–997. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.01.129 (2013).

Stringer, J. M., Alesi, L. R., Winship, A. L. & Hutt, K. J. Beyond apoptosis: evidence of other regulated cell death pathways in the ovary throughout development and life. Hum. Reprod. Update. 29, 434–456. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmad005 (2023).

Dompe, C. et al. Human granulosa cells-Stemness Properties, Molecular Cross-talk and Follicular Angiogenesis. Cells 10 https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10061396 (2021).

Jiang, Q. et al. ANGPTL4 inhibits granulosa cell proliferation in polycystic ovary syndrome by EGFR/JAK1/STAT3-mediated induction of p21. Faseb J. 37 https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.202201246RR (2023).

Liu, X. et al. Novel PGK1 determines SKP2-dependent AR stability and reprograms granular cell glucose metabolism facilitating ovulation dysfunction. Ebiomedicine 61 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.103058 (2020).

Hashimoto, I. & Oshima, T. Claudins and gastric Cancer: an overview. Cancers 14 https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14020290 (2022).

Nah, W. H., Lee, J. E., Park, H. J., Park, N. C. & Gye, M. C. Claudin-11 expression increased in spermatogenic defect in human testes. Fertil. Steril. 95, 385–388. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.08.023 (2011).

Li, C. F. et al. Snail-induced claudin-11 prompts collective migration for tumour progression. Nat. Cell Biol. 21, 251–. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41556-018-0268-z (2019).

Riedhammer, K. M. et al. <i > De novo stop-loss variants in < i > CLDN11 cause hypomyelinating leukodystrophy (144, pg 411, 2020)</i >. Brain 144 https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awab034 (2021).

Li, Y. et al. MALAT1 maintains the intestinal mucosal homeostasis in Crohn’s Disease via the miR-146b-5p-CLDN11/NUMB pathway. J. Crohns Colitis. 15, 1542–1557. https://doi.org/10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjab040 (2021).

Liu, K. et al. Unveiling the oncogenic role of CLDN11-secreting fibroblasts in gastric cancer peritoneal metastasis through single-cell sequencing and experimental approaches. Int. Immunopharmacol. 129 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2024.111647 (2024).

Ling, M. et al. VEGFB promotes myoblasts proliferation and differentiation through VEGFR1-PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms222413352 (2021).

Ediriweera, M. K., Tennekoon, K. H. & Samarakoon, S. R. Role of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway in ovarian cancer: Biological and therapeutic significance. Sem. Cancer Biol. 59, 147–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semcancer.2019.05.012 (2019).

Li, H. P. et al. Inactivation of the tight junction gene < i > CLDN11 by aberrant hypermethylation modulates tubulins polymerization and promotes cell migration in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J. Experimental Clin. Cancer Res. 37 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13046-018-0754-y (2018).

Wissing, M. L. et al. Identification of new ovulation-related genes in humans by comparing the transcriptome of granulosa cells before and after ovulation triggering in the same controlled ovarian stimulation cycle. Hum. Reprod. 29, 997–1010. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/deu008 (2014).

Lizneva, D. et al. Criteria, prevalence, and phenotypes of polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil. Steril. 106, 6–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.05.003 (2016).

Rosenfield, R. L. & Ehrmann, D. A. The pathogenesis of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): the hypothesis of PCOS as functional ovarian hyperandrogenism revisited. Endocr. Rev. 37, 467–520. https://doi.org/10.1210/er.2015-1104 (2016).

Liu, X. et al. Novel PGK1 determines SKP2-dependent AR stability and reprograms granular cell glucose metabolism facilitating ovulation dysfunction. EBioMedicine 61, 103058. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.103058 (2020).

Zheng, Q. et al. ANP promotes proliferation and inhibits apoptosis of ovarian granulosa cells by NPRA/PGRMC1/EGFR complex and improves ovary functions of PCOS rats. Cell. Death Dis. 8, e3145. https://doi.org/10.1038/cddis.2017.494 (2017).

Munakata, Y. et al. Gene expression patterns in granulosa cells and oocytes at various stages of follicle development as well as in in vitro grown oocyte-and-granulosa cell complexes. J. Reprod. Dev. 62, 359–366. https://doi.org/10.1262/jrd.2016-022 (2016).

Wang, W., Zhou, Y., Li, W., Quan, C. & Li, Y. Claudins and hepatocellular carcinoma. Biomed. Pharmacother. 171, 116109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2023.116109 (2024).

Raya-Sandino, A. et al. Claudin-23 reshapes epithelial tight junction architecture to regulate barrier function. Nat. Commun. 14, 6214. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-41999-9 (2023).

Gow, A. et al. CNS myelin and sertoli cell tight junction strands are absent in Osp/claudin-11 null mice. Cell 99, 649–659. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81553-6 (1999).

Zhang, X. Z. et al. lncRNA PCAT18 inhibits proliferation, migration and invasion of gastric cancer cells through miR-135b suppression to promote CLDN11 expression. Life Sci. 249, 117478. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117478 (2020).

Maruhashi, R. et al. Chrysin enhances anticancer drug-induced toxicity mediated by the reduction of claudin-1 and 11 expression in a spheroid culture model of lung squamous cell carcinoma cells. Sci. Rep. 9, 13753. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-50276-z (2019).

Zhang, X., Zhang, H., Zhu, L. & Xia, L. Ginger inhibits the invasion of ovarian cancer cells SKOV3 through CLDN7, CLDN11 and CD274 m6A methylation modifications. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 24, 145. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-024-04431-3 (2024).

Xie, F. et al. Melatonin ameliorates ovarian dysfunction by regulating autophagy in PCOS via the PI3K-Akt pathway. Reproduction 162, 73–82. https://doi.org/10.1530/REP-20-0643 (2021).

Li, X. et al. Isorhamnetin promotes Estrogen Biosynthesis and Proliferation in Porcine Granulosa cells via the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. J. Agric. Food Chem. 69, 6535–6542. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.1c01543 (2021).

Cai, Z., He, S., Li, T., Zhao, L. & Zhang, K. Plumbagin inhibits proliferation and promotes apoptosis of ovarian granulosa cells in polycystic ovary syndrome by inactivating PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway. Anim. Cells Syst. (Seoul). 24, 197–204. https://doi.org/10.1080/19768354.2020.1790416 (2020).

Gao, Y. et al. USP25 regulates the proliferation and apoptosis of ovarian granulosa cells in polycystic ovary syndrome by modulating the PI3K/AKT pathway via Deubiquitinating PTEN. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 9, 779718. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2021.779718 (2021).

Hu, Y. et al. Fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21) promotes porcine granulosa cell estradiol production and proliferation via PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling. Theriogenology 194, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.theriogenology.2022.09.020 (2022).

Sun, X. et al. Neuromedin S regulates steroidogenesis and proliferation in goat leydig cells through modulating mitochondrial function. FASEB J. 37, e22989. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.202300187R (2023).

Myers, M., Britt, K. L., Wreford, N. G., Ebling, F. J. & Kerr, J. B. Methods for quantifying follicular numbers within the mouse ovary. Reproduction 127, 569–580. https://doi.org/10.1530/rep.1.00095 (2004).

Acknowledgements

Graphical abstract illustrations were created online via Biorender, and the data analysis process was facilitated by Hangzhou Lianchuan Biotechnology Co., Ltd.

Funding

Funding for this work was provided by the Natural Science Foundation of Jilin Province (NO 3D523904429).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, M.W, L.Z, and B.Z.; methodology, M.W., and L.Z.; software, T.C., and J.Z; validation, M.W., and C.S.; formal analysis, M.W., and T.C.; investigation, G.H.; resources, J.Z.; data curation, M.W.; writing—original draft preparation, M.W.; writing—review and editing, M.W., J.Z., L.Z., and B.Z.; visualization, L.Z.; supervision, L.Z.; project administration, B.Z.; funding acquisition, J.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, M., Chen, T., Zheng, J. et al. The role of CLDN11 in promotion of granulosa cell proliferation in polycystic ovary syndrome via activation of the PI3K-AKT signalling pathway. Sci Rep 15, 3533 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88189-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88189-9

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Social jetlag elicits fatty liver via perturbed circulating prolactin rhythm-mediated circadian remodeling of hepatic lipid metabolism

Military Medical Research (2025)

-

Comparative effects of streptozotocin, dehydroepiandrosterone and letrozole with high fat diet on ovarian injury induction and functional impairment

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Mechanistic study on the role of multi-pathway autophagy in ovarian aging: literature review

Apoptosis (2025)