Abstract

This study investigated the effect of surgery on the prognosis of patients with primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL) using data from the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results (SEER) database. A cohort of 5932 patients was analyzed, with 1466 undergoing surgical intervention (780 subtotal resection (STR), 686 gross total resection (GTR)) and 4466 receiving no surgery or biopsy only. The median age of the study population was 61.5 years. The median survival was 24.0 months for STR, 30.0 months for GTR, and 18.0 months for non-surgical patients (P < 0.001). Multivariate Cox regression analyses showed that the adjusted hazard ratio (HR) for STR was 0.77 (95% CI 0.70–0.85, P < 0.001) for overall survival (OS) and 0.74 (95% CI 0.66–0.83, P < 0.001) for cancer-specific survival (CSS). For GTR, the adjusted HR was 0.73 (95% CI 0.65–0.80, P < 0.001) for OS and 0.73 (95% CI 0.65–0.82, P < 0.001) for CSS. These results remained robust even after subgroup analyses, sensitivity analyses and propensity score matching (PSM). No significant interactions were observed in any subgroup. These findings indicate that surgery may improve the survival of patients with PCNSL, though further research is needed to confirm these findings. A key limitation is the inability to stratify patients by performance status and lesion number, critical for assessing resective surgery suitability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL) is an extranodal non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) affecting the brain, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), spine, or vitreoretinal space1,2,3. PCNSL is a rare cancer with an annual incidence of 0.4 per 100,000, accounting for 4–6% of extranodal lymphomas and about 4% of newly diagnosed malignant brain tumors4,5,6. Most PCNSLs are diffuse large B-cell lymphomas, primarily affecting the elderly and immunocompromised individuals4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13.The majority of PCNSLs are diffuse large B-cell lymphomas7,8,9,10,11. The disease primarily affects the elderly4,6,12,13 and has compromised immune systems4,6. PCNSL is associated with a worse prognosis than systemic lymphomas of the same histology, with a 5 year survival rate of 15–30%11,14,15. The management of PCNSL is controversial due to the disease’s complexity and limited controlled studies, with no standardized treatment approach16.Current management includes stereotactic needle biopsy for diagnosis, followed by high-dose methotrexate-based chemotherapy17. Cytoreductive surgery is not the standard treatment.

Some studies suggest that surgery may be associated with improved outcomes, whereas others raise concerns about increased neurotoxicity and the potential for tumor dissemination. Rae, BS18 found that craniotomy was associated with increased survival compared with biopsy for PCNSL in three retrospective datasets. In contrast, Guro Jahr19 concluded that resection surgery does not significantly improve overall survival (OS) or progression-free survival (PFS); therefore, it is not recommended as a treatment for PCNSL. However, the role of surgical resection in the treatment of PCNSL remains unclear. Currently, there is no definitive consensus on whether resection or biopsy is recommended for these patients8,16. To date, only a few studies have explored the effect of surgical resection of PCNSL on OS and PFS20.

This study aimed to investigate the effect of surgery on the prognosis of patients with PCNSL and offer insights into future directions for research and clinical practice.

Methods

Study design

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of patients diagnosed with PCNSL who underwent either surgical or nonsurgical treatment. Data were sourced from the Surveillance, epidemiology, and end results database (SEER) version 8.4.3, encompassing information from 17 registries between 2000 and 2021. This study adhered to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE)guidelines for cohort studies21,22. Because the data used were publicly available from the SEER database, informed consent and ethical approval were not required.

Inclusion criteria for participants

Patients diagnosed with PCNSL were identified and classified using a combination of anatomical and histological codes from the international classification of diseases for oncology, 3rd edition (ICD-O-3). Patients diagnosed with PCNSL were identified and classified based on the anatomical and histological codes from the international classification of diseases for oncology, 3rd edition (ICD-O-3). The ICD-O-3 site codes for PCNSL encompassed C70.0,C70.1, C70.9,C71.0–C72.3,C72.5,C72.8 and C72.9 , while the histological codes included 9590/3,9591/3,9596/3,9670/3,9671/3,9673/3,9675/3,9678/3,9680/3, 9680/3,9684/3, 9687/3,9680/3,9684/3,9687/3,9688/3,9690/3,9690/3,9691/3,9695/3, 9698/3,9699/3, 9702/3,9705/3,9712/3,9714/3,9719/3,9727/3,9728/3,9827/3. We meticulously selected patients diagnosed with PCNSL between 2000 and 2021, ensuring that all the patients had histological confirmation.

Data sources/measurement

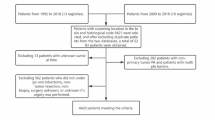

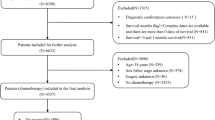

To ensure data accuracy, we excluded individuals without a histological diagnosis or autopsy confirmation of PCNSL. Additionally, we excluded patients for whom surgery was recommended, but the actual administration of the treatment was uncertain. From 2000 to 2021, 8587 patients diagnosed with PCNSL were identified in the SEER database based on predefined criteria. Exclusions were made for cases with incomplete or inaccurate information, such as missing diagnoses, surgical interventions, initial cancer indicators, and short survival duration (survival time of less than three months was deemed non-informative for efficacy assessment). Consequently, the analytical cohort was refined to encompass 5932 individuals. Patients were divided into groups based on their surgical treatment status. Among the total cohort, 1,466 individuals underwent surgery, including 780 with subtotal resection (STR) and 686 with gross total resection (GTR). Additionally, 986 patients underwent biopsy only, whereas 3480 did not receive any surgical intervention. A visual representation of the study enrollment process is presented in (Fig. 1).

Statistical analyses

We conducted a descriptive analysis of the participants in our study. Categorical variables are expressed as frequencies and percentages, and continuous variables are described as medians along with their interquartile ranges. Chi-square tests were used to compare categorical variables. The Kruskal–Wallis test was used for continuous variables with skewed distribution.

Multivariate Cox regression analysis was performed to investigate the independent relationship between surgery and survival. The primary endpoints were overall survival (OS) and cancer-specific survival (CSS). Survival curves were generated using Kaplan–Meier (K–M) analysis, with the log-rank test used to compare patient groups who underwent surgery versus those who did not. Subgroup analyses were performed to assess the association between surgery and survival outcomes, after adjusting for potential confounders. Interaction tests in Cox proportional hazards models were used to compare the hazard ratios (HRs) across subgroups. Propensity score matching (PSM) was employed to minimize bias in baseline characteristics, utilizing a 1:1 matching ratio and a caliper of 0.2.

All analyses were performed using R Statistical Software (Version 4.2.2, http://www.R-project.org, The R Foundation) and Free Statistics Analysis Platform (Version 1.9, Beijing, China23. Statistical significance was established at a two-tailed p-value of less than 0.05.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Table 1 presents the baseline demographic characteristics of all participants. Of the total cohort, 1,466 individuals (24.7%) underwent surgery, including STR (n = 780) and GTR (n = 686), while 4,466 (75.3%) were classified as non-surgical recipients (including 3480 individuals without a histological diagnosis of PCNSL from the primary lesion and 986 individuals who underwent biopsy only). The median age of the study population was 61.5 years. The median survival time was 24.0 months for patients who underwent STR, 30.0 months for patients who underwent GTR and 18.0 months for those without surgery treatment (P < 0.001). Significant differences were observed in age (P = 0.007), histologic subtype (P = 0.041), laterality (P < 0.001), time from diagnosis to treatment (p = 0.006), median household income (P = 0.017), and chemotherapy (P = 0.030) based on surgery treatment status.

Univariate Cox regression analyses

As shown in Table 2, patients who underwent surgery showed a significant reduction in mortality (OS: HR 0.78, 95% CI 0.72–0.84; P < 0.001; CSS: HR 0.76, 95% CI 0.70–0.83, P < 0.001). Similarly, chemotherapy was associated with a significant decrease in mortality (OS: HR 0.50, 95% CI 0.46–0.53; P < 0.001; CSS: HR 0.49, 95% CI 0.45–0.53; P < 0.001). In contrast, patients who received radiation (OS: HR 1.19, 95% CI 1.11–1.27, P < 0.001; CSS: HR, 1.21; 95% CI 1.13–1.30, P < 0.001) experienced a significant reduction in survival. In addition, female sex, patients more than 65 years, years of diagnosis 2011–2021, unknown time from diagnosis to treatment, unknown primary site, and lower median household income were associated with an increased risk of mortality (all P < 0.05, for both OS and CSS). No significant differences in mortality were found with respect to race, marital status, histologic subtype, laterality, or rural urban continuum (all P > 0.05, for both OS and CSS).

Multivariate Cox regression analyses

Table 3 presents the results of the multivariate Cox regression analyses examining the impact of surgery on OS and CSS. In the initial analysis, the patients who underwent STR showed a significant reduction in mortality (OS: HR 0.79, 95% CI 0.72–0.88; P < 0.001; CSS: HR 0.76, 95% CI 0.68–0.85; P < 0.001). Similarly, those who underwent GTR also experienced lower mortality rates (OS: HR 0.76, 95% CI 0.68–0.85, P < 0.001; CSS: HR 0.76, 95% CI 0.68–0.85, P < 0.001). In minimally adjusted Model 1, controlling for age, sex, race, marital status, and median household income, the results remained consistent, with significant reductions in mortality for both STR (OS: HR 0.79, 95% CI 0.72–0.88, P < 0.001; CSS: HR 0.76, 95% CI 0.68–0.85, P < 0.001) and GTR (OS: HR 0.76, 95% CI 0.68–0.85, P < 0.001; CSS: HR 0.76, 95% CI 0.68–0.85, P < 0.001). In Model 2, which included additional adjustments for years of diagnosis, primary site, histologic subtype, laterality, time from diagnosis to treatment, and rural–urban continuum, the findings remained significant. STR (OS: HR 0.79, 95% CI 0.72–0.88, P < 0.001; CSS: HR 0.76, 95% CI 0.68–0.85, P < 0.001) and GTR (OS: HR 0.76, 95% CI 0.68–0.85, P < 0.001; CSS: HR 0.76, 95% CI 0.68–0.85, P < 0.001) continued to demonstrate lower mortality rates. In the fully adjusted Model 3, the adjusted HR for STR were 0.77 (95% CI 0.70–0.85, P < 0.001) for OS and 0.74 (95% CI 0.66–0.83, P < 0.001) for CSS. For GTR, the adjusted HR were 0.73 (95% CI 0.65–0.80, P < 0.001) for OS and 0.73 (95% CI 0.65–0.82, P < 0.001) for CSS. Overall, these findings indicate that surgical intervention is linked to a notably reduced mortality rate compared with non-surgical options.

Subgroup analyses and interaction

Subgroup analyses were performed in different subgroups to evaluate possible effect modifications in the association between surgery and OS and CSS. The findings revealed a statistically significant correlation between surgery and decreased mortality rates across various subgroups stratified by age, sex, marital status, histologic subtype, radiation, and chemotherapy, aligning with the overall study outcomes (Fig. 2). This indicated that the association between surgery and OS and CSS remained robust across these demographic and treatment-related factors. Furthermore, no significant interactions were observed in any subgroup analysis.

The relationship between surgery and OS (A) and CSS (B) according to basic features. Except for the stratification component itself, each stratification factor was adjusted for all other variables (age, sex, race, marital status, median household income, years of diagnosis, primary site, histologic subtype, laterality, time from diagnosis to treatment, rural–urban continuum, radiation and chemotherapy). OS overall survival, CSS cancer-specific survival, STR subtotal resection, GTR gross total resection, DLBCL diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

Sensitivity analyses

PSM analyses were conducted to mitigate the impact of potential confounding factors, including baseline medical and demographic characteristics. Supplementary Table 1 provides a comparison of the descriptive statistics for these variables both prior to and following PSM, illustrating the efficacy of the method in minimizing selection bias. The K-M curves indicated that the surgical group had a significantly higher survival rate than the non-surgical group before and after PSM (all P < 0.0001 for OS and CSS, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 1). Multivariate Cox regression analysis supported these findings, showing a lower HR for patients undergoing surgery than for those receiving non-surgical treatment (OS: HR 0.74, 95% CI 0.67–0.81, P < 0.001; CSS: HR 0.75, 95% CI 0.67–0.98, P < 0.001, see Supplementary Table 2). Furthermore, we employed multiple statistical techniques to adjust the propensity scores, and the HRs remained stable across analyses (OS: HR 0.75, 95% CI 0.69–0.81, P < 0.001; CSS: HR 0.73, 95% CI 0.68–0.80, P < 0.001), as outlined in (Table 4).

Survival analyses

As shown in Fig. 3, the Kaplan–Meier (K-M) curves indicated that the OS and CSS in the surgical group were significantly higher than those in the nonsurgical group (both P < 0.0001). The 1-year OS rates were 58.0% (56.6–59.5%) in the non-surgery group, 64.6.0% (61.2–68.0%) in the STR group, and 70.9% (67.6–74.4%) in the GTR group. Similarly, the 1-year CSS rates were 61.1% (59.6–62.5%) in the non-surgery group, 68.2% (65.0–71.6%) in the STR group, and 73.5% (70.2–76.9%) in the GTR group. At 3 years, the OS rates decreased to 43.9% (42.4–45.5%) in the non-surgery group, 53.5% (50.0–57.2%) in the STR group, and 55.8% (52.1–59.8%) in the GTR group. Correspondingly, the 3-year CSS rates were 48.1% (46.5–49.6%) for the non-surgery group, 58.3% (54.7–62.0%) for the STR group, and 59.9% (56.1–63.9%) in the GTR group. By 5 years, the OS rates further declined to 37.0% (35.5–38.6%) in the non-surgery group, 46.4% 42.8–50.3%) in the STR group, and 48.1% (44.3–52.3%) in the GTR group. The 5-year CSS rates were 42.5% (41.0–44.1%) in the non-surgery group, 52.7% (49.1–56.7%) in the STR group, and 53.2% (49.3–57.4%) in the GTR group.

Discussion

Our population-based study utilizing the SEER database provided insights into the role of surgery in the treatment of PCNSL. Our findings showed that both STR and GTR were linked to improved survival compared to non-surgery, with a trend indicating that more extensive resection correlates with longer survival. These outcomes were supported by multivariate analysis, subgroup analysis, sensitivity analysis, and PSM, which confirmed the persistent benefits of surgery.

Our results are consistent with those of other studies that advocate for the inclusion of surgery in the treatment of PCNSL. The association between craniotomy and improved survival compared with biopsy for PCNSL was first demonstrated by Weller et al.24. Jelicic et al.25 found that total tumor resection was significantly associated with increased OS. Villalonga26 confirmed that patients who underwent surgical resection had a median survival of 16.5 months longer than those who only had a biopsy. Rae, BS18 indicated that craniotomy is linked to improved survival over biopsy for PCNSL based on three retrospective datasets. Ouyang9 noted that surgical excision can enhance progression-free survival (PFS) in intracranial PCNSL. Singh et al.27 suggested that cytoreductive surgery may provide potential benefits for selected PCNSL patients, showing trends toward improved OS, reduced time-to-treatment response (TTR), increased rate of complete resection (RIC), and lower requirements for whole-brain radiotherapy (WBRT). A meta-analysis that included seven studies (n = 1046)8,9,18,24,26,28,29 validated that in selected patients, surgical resection of PCNSL significantly improved both OS and PFS compared with biopsy alone30. Our study showed that surgery significantly improved survival in PCNSL, with adjusted HRs of 0.77 for OS and 0.74 for CSS for STR, and 0.73 for both OS and CSS for GTR (all P < 0.001). These results indicate that surgery can improve survival in patients with PCNSL compared to non-surgical approaches. These findings provide strong evidence supporting the role of surgical intervention in improving survival outcomes in a large, diverse observational cohort derived from real-world clinical practice.

Nevertheless, clear and universally accepted guidelines for the use of surgery in patients with PCNSL are still lacking31. Surgery has been the subject of debate in the treatment paradigm of PCNSL because of the deep-seated nature of these tumors and the associated risks of neurosurgical intervention. However, with advancements in neurosurgical techniques and a better understanding of disease biology, indications for surgery have expanded. Surgical resection offers several potential benefits, including histological confirmation, reduction of tumor burden, and alleviation of the mass effect, which can be crucial in cases of neurological deterioration or increased intracranial pressure. Despite these potential benefits, the optimal extent of the surgical intervention remains controversial. Some studies have indicated that surgical treatment does not enhance the prognosis of PCNSL and provides no additional benefit. An analysis of 248 PCNSL cases treated at 19 French and Belgian medical centers from 1980 to 1995 found that the 1-year survival rates were 31.8% for partial resections, 56.6% for complete resections, and 48.6% for stereotactic biopsies (P = 0.040). The authors concluded that partial resection is associated with significantly poorer survival and recommended stereotactic biopsy for diagnosis32. In a European study of 25 PCNSL patients treated with gross or partial resection due to symptoms of increased intracranial pressure, surgery helped manage acute neurological deterioration but did not improve survival compared to stereotactic biopsy alone33. Vito Stifand conducted a meta-analysis of 11 studies8,9,10,18,26,28,29,34,35,36,37. Meta-regression analysis indicated that surgery may be non-inferior to biopsy in selected patients with single and superficial lesions while maintaining an acceptable risk profile. However, the overall quality of the evidence was low, highlighting the need for future randomized studies. According to Guro Jahr29, a 12-year review of a prospective database at Oslo University Hospital for PCNSL included 32 patients who underwent craniotomy with resection, while the remaining patients underwent biopsy. Multivariate analysis revealed that resection surgery did not significantly improve OS or PFS, and was not recommended as a treatment for PCNSL. These conclusions require further confirmation. While the current data suggest that resection does not significantly improve survival, future studies may provide additional evidence to clarify the role and applicability of surgery in the treatment of PCNSL. In subgroup analysis, subtotal resection in DLBCL of PCNSL provides marginal benefits may due to tumor infiltration, high recurrence rates, and the effectiveness of chemotherapy. Additionally, aggressive resection carries neurological risks without substantially affecting long-term survival.

Chemotherapeutic regimens for PCNSL are generally less effective than those for systemic lymphoma. High-dose methotrexate (HD-MTX)-based chemotherapy is widely recommended as an effective first-line treatment for PCNSL, demonstrating improved survival outcomes13,16,38,39. Combining HD-MTX with other chemotherapy agents may offer additional benefits compared with HD-MTX alone38,40,41. Although several studies have assessed the role of radiotherapy in PCNSL treatment, the results remain inconclusive17. Recent research suggests that adjuvant radiotherapy, when combined with surgery, can enhance survival rates42. The benefits of surgery observed in our study may be due to the precise removal of the tumor mass, which helps reduce the tumor burden and enhances the effectiveness of subsequent therapies. Additionally, surgery enables an accurate histopathological diagnosis, which is essential for personalized treatment strategies. Given the significant morbidity and mortality associated with the location of CNS tumors, surgical resection can rapidly alleviate neurological symptoms and provide more time for medical treatment to take effect.

Our study has several notable strengths, including its large sample size and population-based design. Our findings indicate that surgery may provide a survival advantage for patients with PCNSL. This prompts a re-evaluation of treatment protocols, advocating for a multidisciplinary approach that considers surgery as a viable option alongside radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Future studies should address the gaps identified in our analysis, particularly through randomized controlled trials that can provide higher-level evidence for the role of surgery in PCNSL management. Additionally, research on the molecular stratification of PCNSL may reveal subsets of patients who stand to benefit the most from surgical intervention.

The retrospective nature of our study, inherent to the utilization of SEER data, introduces potential biases that could influence observed outcomes. Although the PSM method was applied in our study, selection bias remains an unavoidable limitation owing to its retrospective design. Unmeasured confounders, such as patient performance status and comorbidities, may affect the decision to operate and the subsequent survival. Additionally, the variability in surgical techniques and the lack of detailed procedural data in SEER limit our ability to fully elucidate the nuances of the surgical impact. The SEER database only provides information on whether patients received chemotherapy or radiation therapy, without details on specific regimens, types, dosages, or schedules, limiting treatment assessment. Additionally, detailed data on patients’ general health and lesion pathology, such as operability, are unavailable. Therefore, future prospective studies with larger sample sizes are required to validate our findings.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our population-based analysis highlights the potential role of surgery in improving the survival outcomes of patients with PCNSL. While our findings support the consideration of surgery in treatment planning, they also underscore the need for further investigation to refine indications and optimize patient selection for surgical intervention.

Data availability

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. These data are available at www.seer.cancer.gov.

References

Schaff, L. R. & Grommes, C. Primary central nervous system lymphoma. Blood 140, 971–979. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2020008377 (2022).

Grommes, C. & DeAngelis, L. M. Primary CNS lymphoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 35, 2410–2418. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2017.72.7602 (2017).

Grommes, C. Central nervous system lymphomas. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 26, 1476–1494. https://doi.org/10.1212/CON.0000000000000936 (2020).

Villano, J. L., Koshy, M., Shaikh, H., Dolecek, T. A. & McCarthy, B. J. Age, gender, and racial differences in incidence and survival in primary CNS lymphoma. Br. J. Cancer 105, 1414–1418. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2011.357 (2011).

Mendez, J. S. et al. The elderly left behind-changes in survival trends of primary central nervous system lymphoma over the past 4 decades. Neuro Oncol. 20, 687–694. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/nox187 (2018).

Shiels, M. S. et al. Trends in primary central nervous system lymphoma incidence and survival in the US. Br. J. Haematol. 174, 417–424. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.14073 (2016).

Giannini, C., Dogan, A. & Salomão, D. R. CNS lymphoma: a practical diagnostic approach. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 73, 478–494. https://doi.org/10.1097/NEN.0000000000000076 (2014).

Schellekes, N. et al. Resection of primary central nervous system lymphoma: impact of patient selection on overall survival. J. Neurosurg. 135, 1016–1025. https://doi.org/10.3171/2020.9.JNS201980 (2021).

Ouyang, T. Clinical characteristics, surgical outcomes, and prognostic factors of intracranial primary central nervous system lymphoma. World Neurosurg. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2020.04.049 (2020).

Thiel, E. et al. High-dose methotrexate with or without whole brain radiotherapy for primary CNS lymphoma (G-PCNSL-SG-1): a phase 3, randomised, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Oncol. 11, 1036–1047. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70229-1 (2010).

Ferreri, A. J. M. et al. International extranodal lymphoma study group (IELSG), High-dose cytarabine plus high-dose methotrexate versus high-dose methotrexate alone in patients with primary CNS lymphoma: a randomised phase 2 trial. Lancet 374, 1512–1520. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61416-1 (2009).

CBTRUS Statistical report: Primary brain and other central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2009–2013. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28475809/ (accessed 28 October 2024).

Kasenda, B. et al. First-line treatment and outcome of elderly patients with primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL)—A systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis. Ann. Oncol. 26, 1305–1313. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdv076 (2015).

First-line treatment and outcome of elderly patients with primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL)—A systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25701456/ (accessed 24 October 2024).

Batchelor, T. & Loeffler, J. S. Primary CNS lymphoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 24, 1281–1288. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2005.04.8819 (2006).

Hoang-Xuan, K. et al. European association of neuro-oncology (EANO) guidelines for treatment of primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL). Neuro Oncol. 25, 37–53. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/noac196 (2023).

Hoang-Xuan, K. et al. European association for neuro-oncology task force on primary CNS lymphoma, diagnosis and treatment of primary CNS lymphoma in immunocompetent patients: guidelines from the European association for neuro-oncology. Lancet Oncol. 16, e322-332. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00076-5 (2015).

Rae, A. I. et al. Craniotomy and survival for primary central nervous system lymphoma. Neurosurgery 84, 935–944. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuros/nyy096 (2019).

Jahr, G., Da Broi, M., Holte, H., Beiske, K. & Meling, T. R. The role of surgery in intracranial PCNSL. Neurosurg. Rev. 41, 1037–1044. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-018-0946-0 (2018).

Stifano, V. et al. Resection versus biopsy for management of primary central nervous system lymphoma: a meta-analysis. Neurosurg. Rev. 46, 37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-022-01931-z (2023).

World Medical Association. World Medical association declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 310, 2191–2194. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.281053 (2013).

von Elm, E. et al. STROBE initiative, the strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet 370, 1453–1457. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61602-X (2007).

Li, G. P. et al. Association between the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and cancer in adults from NHANES 2005–2018: a cross-sectional study. Sci. Rep. 14, 23678. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75252-0 (2024).

Weller, M., Martus, P., Roth, P., Thiel, E. & Korfel, A. German PCNSL study group, surgery for primary CNS lymphoma? Challenging a paradigm. Neuro Oncol. 14, 1481–1484. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/nos159 (2012).

Jelicic, J. et al. The possible benefit from total tumour resection in primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of central nervous system—A one-decade single-centre experience. Br. J. Neurosurg. 30, 80–85. https://doi.org/10.3109/02688697.2015.1071328 (2016).

Villalonga, J. F. et al. The role of surgery in primary central nervous system lymphomas. Arq. Neuropsiquiatr. 76, 139–144. https://doi.org/10.1590/0004-282x20180002 (2018).

Singhal, S., Antoniou, E., Kwan, E., Gregory, G. & Lai, L. T. Cytoreductive surgery for primary central nervous system lymphoma: Is it time to consider extent of resection?. J. Clin. Neurosci. 106, 110–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocn.2022.10.008 (2022).

Wu, S. et al. The role of surgical resection in primary central nervous system lymphoma: a single-center retrospective analysis of 70 patients. BMC Neurol. 21, 190. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-021-02227-3 (2021).

Jahr, G. The role of surgery in intracranial PCNSL. Neurosurg. Rev. 41, 1037–1044 (2018).

Chojak, R. et al. Surgical resection versus biopsy in the treatment of primary central nervous system lymphoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Neurooncol. 160, 753–761. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-022-04200-7 (2022).

Bierman, P. J. Surgery for primary central nervous system lymphoma: is it time for reevaluation?. Oncology 28, 632 (2014).

Bataille, B. et al. Primary intracerebral malignant lymphoma: report of 248 cases. J. Neurosurg. 92, 261–266. https://doi.org/10.3171/jns.2000.92.2.0261 (2000).

Bellinzona, M., Roser, F., Ostertag, H., Gaab, R. M. & Saini, M. Surgical removal of primary central nervous system lymphomas (PCNSL) presenting as space occupying lesions: a series of 33 cases. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. (EJSO) 31, 100–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2004.10.002 (2005).

Gelabert-González, M., Castro Bouzas, D., Serramito-García, R., Frieiro Dantas, C. & Aran Echabe, E. Linfomas primarios del sistema nervioso central. Neurología 28, 283–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nrl.2012.04.005 (2013).

Multi-modality therapy leads to longer survival in primary central nervous system lymphoma patients. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12035835/ (accessed 28 October, 2024).

Tseng, M. Y., Tu, Y. K. & Shun, C. T. Primary central nervous system lymphoma: a retrospective study. J. Clin. Neurosci. 5, 409–412. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0967-5868(98)90273-9 (1998).

Primary central nervous system lymphoma: Variety of clinical manifestations and surviva|Acta Neurochirurgica. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01411738 (accessed 28 October 2024).

Li, Q. et al. Improvement of outcomes of an escalated high-dose methotrexate-based regimen for patients with newly diagnosed primary central nervous system lymphoma: a real-world cohort study. Cancer Manag. Res. 13, 6115–6122. https://doi.org/10.2147/CMAR.S322467 (2021).

Yu, J., Du, H., Ye, X., Zhang, L. & Xiao, H. High-dose methotrexate-based regimens and post-remission consolidation for treatment of newly diagnosed primary CNS lymphoma: meta-analysis of clinical trials. Sci. Rep. 11, 2125. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-80724-0 (2021).

Ferreri, A. J. M. et al. IELSG32 study investigators, Long-term efficacy, safety and neurotolerability of MATRix regimen followed by autologous transplant in primary CNS lymphoma: 7-year results of the IELSG32 randomized trial. Leukemia 36, 1870–1878. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-022-01582-5 (2022).

Ferreri, A. J. M. et al. International extranodal lymphoma study group (IELSG), chemoimmunotherapy with methotrexate, cytarabine, thiotepa, and rituximab (MATRix regimen) in patients with primary CNS lymphoma: results of the first randomisation of the international extranodal lymphoma study group-32 (IELSG32) phase 2 trial. Lancet Haematol. 3, e217-227. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3026(16)00036-3 (2016).

Kinslow, C. J. et al. Surgery plus adjuvant radiotherapy for primary central nervous system lymphoma. Br. J. Neurosurg. 34, 690–696. https://doi.org/10.1080/02688697.2019.1710820 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We thank the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program (National Cancer Institute) for the development of the SEER database. Special thanks go to Dr. Jie Liu from the Department of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery at the Chinese PLA General Hospital.

Funding

This project was supported by Henan Province Science and Technology Research and Development Plan (No. LHGJ20220188, SBGJ202102069), Henan Province Young and Middle-aged Talent Plan Project (No. YXKC2022046).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Di Zhang and Dongjie He designed the study and revised the manuscript. Gangping Li and Xinjiang Hou performed the research and assisted in data collection. Yuewen Fu collected the clinical data. Gangping Li analysed the data and wrote the paper. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All studies were approved by the relevant ethical review board, Due to the retrospective nature of the study, ethical review board waived the need of obtaining informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, G., Hou, X., Fu, Y. et al. Association between surgery and increased survival in primary central nervous system lymphoma: a retrospective cohort study. Sci Rep 15, 3816 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88351-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88351-3