Abstract

Recent studies have utilized time-restricted feeding (16/8) (TRF) and dietary approaches to stop hypertension separately to manage metabolic-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD); however, the effectiveness of combining these two approaches has not been investigated. The objective of this study was to examine the impact of TRF in conjunction with a DASH diet on various factors related to MAFLD. A 12-week randomized controlled trial was conducted to assess the impact of TRF (16/8), along with a DASH diet, compared with a control diet based on standard meal distribution, in patients with MAFLD. An investigation was conducted to examine alterations in anthropometric indices, as well as liver parameters, serum metabolic indices, and an inflammatory marker. The TRF plus DASH diet reduced body mass index (p = 0.03), abdominal circumference (p = 0.005), controlled attenuation parameter (CAP) (p < 0.001), alanine aminotransferase (p = 0.039), and aspartate aminotransferase (0.047) compared to the control group. The levels of insulin and homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance reduced in both groups significantly (P < 0.05). In MAFLD patients, TRF (16/8) in combination with a DASH diet is superior to a low-calorie diet in promoting obesity indices, and hepatic steatosis and fibrosis. Further long-term investigations are needed to draw definitive conclusions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Metabolic associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) is a frequent and worldwide concern with a global prevalence of 6–35%1. MAFLD is the predominant etiology of chronic liver disease, characterized by the accumulation of lipid droplets in over 5% of hepatocytes, in the absence of substantial alcohol use2,3,4. Environmental factors, genetic, sex and hormonal status should be considered as crucial factors in the developing of MAFLD5,6; nevertheless, the most important cause of death in patients with MAFLD is cardiovascular diseases7 and particularly, it has been seen that people with MAFLD are more likely to develop type 2 diabetes mellitus8.The accumulation of triglycerides causes oxidative stress, protein misfolding and mitochondrial damage which ultimately leads to chronic inflammatory response confirmed by the presence of high sensitivity c-reactive protein (hs-CRP) have been recognized as pathogenic factors that contribute to MAFLD9. Dietary interventions are known as the most effective approach for management of MAFLD due to the absence of any approved pharmacological therapy10,11,12.

Intermittent fasting is one of the dietary patterns of calorie restriction which comprises specific periods of fasting13. During fasting, the level of ketone bodies in the blood is raised to produce energy from triglycerides, which has beneficial metabolic effects such as improving glucose regulation, blood pressure and reducing inflammation, independent of its effects on weight loss14,15,16. One type of intermittent fasting that offers time-limited possibilities for food intake throughout the day is called time-restricted feeding (TRF). The 16:8 model is the most widely used kind of TRF. It consists of an 8-hour feeding window followed by a 16-hour fasting window17,18. The beneficial effects of Intermittent fasting on different aspects of MAFLD have been reported previously19,20.

Dietary approaches to stop hypertension (DASH), is a pattern of eating that is low in sodium, high in calories, low in glycemic index, high in phytoestrogens, magnesium, potassium, and dietary fiber21. The DASH has less saturated fat, sodium, and sweetened beverages and is high in fruits, vegetables, low-fat or fat-free dairy products, seafood, nuts, and legumes22. Moreover, it has been shown to have beneficial effects on weight, body mass index, liver enzymes, insulin metabolism markers, serum triglycerides, very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL), and hepatic steatosis in overweight and obese patients with MAFLD23,24,25.

Given the rising prevalence of MAFLD around the world and its strong association with other metabolic disorders, such as diabetes, and cardiovascular disease, and due to the lack of randomized clinical studies examining the impact of DASH with TRF on individuals with MAFLD, we designed this study to evaluate the effects of co-administration of DASH and TRF on hepatic parameters, glucose homeostasis, lipid profile and inflammation in patients with MAFLD. It was hypothesized that combining DASH with TRF diet would be an effective strategy in management of MAFLD.

Methods and materials

This randomized controlled trial (RCT) was conducted on patients with MAFLD at the Research Institute for Gastroenterology and Liver Diseases, Tehran, Iran. Inclusion criteria were defined as: age over 18 years, grade 2 MAFLD according to controlled attenuation parameter (CAP) score level of ≥ 260 dB/m, willingness to take part in this study, not having taken medicines such as herbal medicines, anti-inflammatory medications, corticosteroids/any hormone, weight-loss medications, or hepatotoxic medications like phenytoin, amoxicillin, and lithium for > 1 weak before enrolling. In addition, patients should not be diagnosed with uncontrolled cardiovascular diseases, stroke, diabetes, acute liver disorders (hepatitis B, C, etc.), kidney diseases, chronic inflammatory disease, depression, cancer, or autoimmune disease, no history of weight loss surgery or weight loss programs in the last 3 months. Participants who cosumed alcohol were not26 allowed to participate in this study. Only those who met al.l inclusion requirements and were willing to complete the 12 weeks of TRF (16/8) combination with a DASH diet, were included in the study.

Exclusion criteria included current pregnancy or breastfeeding, use of birth control pills during the study, use of drugs that can influence metabolism or liver function (e.g., glucose-lowering agents, blood pressure drugs, and lipid-controlling drugs (, unwillingness to continue the project, and aggravation of the diseases which lead to hospitalization.

Prior to research recruitment, all participants signed a written informed consent form. Registering of the trial was done at www.irct.ir, on 22/07/2023 (IRCT20100524004010N39). The Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Nutrition and Food Technology, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran (IR.SBMU.NNFTRI.REC.1399.019) approved the current trial. The study was conducted according to consort guideline.

Study design and intervention

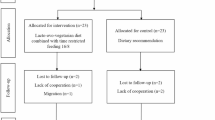

This study was conducted as a randomized clinical trial. Patients who were diagnosed with MAFLD were stratified into groups by BMI and age. They were then randomly assigned to either the TRF (16/8) combined with the DASH group (n = 27) or the non-intervention control group (n = 26) using a computer-generated random-numbers approach. The primary outcomes of the study were liver biomarkers, including enzyme and imaging tests, due to the particular nature of MAFLD. The secondary outcomes included lipid, glycemic, and inflammatory indicators, as well as body composition.

Sample sizes

Various dependent variables were used to determine how many sample sizes would be needed for this study. For the variable that was reliant on the CAP score, the greatest number of samples was obtained. The number of samples that should be chosen to ensure that the average CAP score difference between the intervention group and the control group is at least 27 dB/m. This difference was mentioned as statistically significant when it reached a power of 80% (β = 20%) and probability of 95% (α = 0.05). It was predicted that the sample size for each group would include 21 patients. Using the following formulas and the deviation from the criterion found in a prior study27, the sample size was determined.

Dietary interventions

For a period of 12 weeks, the intervention group was assigned to follow the TRF 16/8 (refraining from eating for 16 h and being allowed to eat for 8 h every day). TRF was chosen over other IF regimens, like alternate-day fasting and Ramadan-style fasting since it might be more practical and convenient for participants. Participants in this group were asked to follow a DASH diet in addition to the TRF program. The DASH diet was low in processed and red meats, and sugar-sweetened beverages, and high in fruits, vegetables, low-fat dairy, and a range of protein sources like fish, chicken, legumes, and nuts22.

The control group was advised to adhere to weight loss diets, which were assessed by a certified dietitian before the commencement of the trial. Nevertheless, this group was also obligated to comply with the calorie intake, macronutrient composition, and consumption of fruits and vegetables as outlined below.

The caloric intake for patients was determined using the Mifflin-St Jeor equation 28 . The recommended macronutrient distribution was set at 30% of total calories from fat, 18% from protein, and 52% from carbohydrates for both groups in addition to consuming 7–8 servings of fruits and vegetables. Total recommended dietary energy was 500 kcal less than maintenance needed energy per day.

The intervention and control groups were permitted to consume non-caloric fluids such as water, coffee, or tea. The patients were instructed to drink water without any limitations during the study. Therefore, these calorie-free liquids were permitted during both fasting and feeding phases. Each patient was assigned a diet plan for 3 months. During the initial phase of this study, all participants received detailed instructions on how to strictly follow the prescribed diet. Throughout the study, their adherence to the diet was closely monitored by weekly phone calls and monthly interviews, which involved recalling their dietary intake over 24 h on three separate days consisting of two weekdays and one holiday. The participants who failed to comply with the prescribed diet were excluded from the study.

Measurements

Body weight, height, abdominal circumference (AC), and body composition were measured for all participants at the start and the end of the trial. Additionally, fasting blood samples were collected in the morning following a 10 to 12-hour period of abstaining from food. In addition, the degree of steatosis and hepatic fibrosis was assessed using the FibroScan® 502 Touch equipment (Echosens, Paris, France) at the beginning and end of the 12-week trial. In addition, the researchers evaluated physical activity levels by utilizing the metabolic equivalent of the task (MET) questionnaire29 and 24-hour recalls (one weekend day and two workdays)30,31 at baseline and end of the study. Furthermore, patients also completed demographic questionnaires. The dietary energy and macronutrient composition were analyzed using Nutritionist IV software, developed by (First Databank Inc., Hearst Corp., San Bruno, CA, USA),

Anthropometric measurements and body composition

Body weight was assessed with precision to the nearest 0.1 kg using a digital scale (Seca 808, Germany) that has an accuracy of ± 0.1 kg. Participants were instructed to wear lightweight clothing throughout the measurement. The participants’ standing height was measured with a wall stadiometer (Seca), using standard protocols32, without shoes, and rounded to the nearest 0.5 cm. The BMI was computed by dividing the weight (in kilograms) by the square of the height (in meters). To mitigate measurement errors, all measurements were conducted by a single individual.

Abdominal circumferences (AC) and waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) were measured using bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA; Tanita-BC 418, Arlington Heights, MA, USA) at the baseline and end of the study33 .The measurements were conducted following 12 h of abstaining from food. Patients were instructed to abstain from ingesting alcoholic beverages for 24 h before the test and to refrain from engaging in physical exercise for 12 h before the test. Participants were instructed to void their bladders 30 min before the test and to promptly remove any metal objects before the test34 .

Blood sample measurements

The participants’ blood samples, measuring 10 mL, were collected between the hours of 7 and 10 A.M. Subsequently, the samples were subjected to centrifugation at a force of 2000 g at room temperature for 20 min35. At the commencement and end of the study, serum biomarkers were examined.

Liver enzymes, including (alanine transaminase (ALT), aspartate transaminase (AST), and gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT), as well as the lipid profile, which includes (total cholesterol (TC), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), and triglycerides (TG)), were measured using the recommended procedures outlined by Delta-dp diagnostic kits (Roche, Germany).

The concentrations of fasting blood glucose (FBG) were determined using an auto analyzer equipped with the glucose oxidase method (Cobas c311, Roche Diagnostics, Risch-Rotkreuz, Switzerland). The ELISA kit (Monobind Inc. Lake Forest, CA, USA) was utilized to assess serum insulin levels.

To evaluate insulin resistance (IR), we computed the homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) and the quantitative insulin sensitivity check index (QUICKI) using the following formulas:

[HOMA-IR = glucose (mg/dL) × insulin (mU/L) /405].

QUICKI = 1/ [log fasting serum insulin (µU/ml) + log fasting plasma glucose (mg/dl)]

The high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) was quantified using the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) technique provided by (ZellBio GmbH, located in Ulm, Germany).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted with SPSS version 22. The data is shown as mean ± SD. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests were utilized to assess how well the data fit the normal distribution. For non-normally distributed data, log transformation was used. The data set comprised only those who successfully finished the RCT, as determined by per-protocol analysis. Quantitative factors were compared between groups using independent sample t-tests at baseline and before and after the intervention for baseline and anthropometric factors. For qualitative variables, chi-squared tests were employed. Quantitative variables within each of the two groups were also compared before and after the intervention using the student’s paired samples t-tests. To compare the means of other variables between groups, analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to adjust the confounding variables (metabolic equivalents, BMI, dietary energy intake, and baseline values of the outcomes). P < 0.05 for statistical significance was applied.

The data were analyzed using both per-protocol, and intention-to-treat (ITT) principle. For ITT analysis, patients missing laboratory measurements of the secondary outcome measures were imputed. A multiple imputation procedure was used based on Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations. In the multiple imputation procedure, 5 imputed data sets were generated. The results of the 5 imputed data sets were pooled to obtain data estimates. Since the results of both analysis were similar, we reported the per-protocol analysis.

Results

Among the 102 patients who were randomly assigned, 9 patients were not interested in participating in the study and 40 patients did not meet inclusion criteria. As a result, there were 27 subjects in the intervention group (TRF with DASH diet) and 26 subjects in the control group. After four weeks of the trial, six more subjects withdrew from the treatment group and five subjects withdrew from the control group due to difficulties in their schedules and personal reasons. Thus, the study was completed by 21 patients in the intervention group and 21 patients in the control group (Fig. 1). The anthropometric factors and baseline characteristics of the participants are shown in (Table 1). There was no significant difference between the groups in age (p = 0.833), gender (p = 0.533), smoking (p = 0.500) and height (p = 0.195).

The data on the anthropometric indices and body composition of the patients is presented in Table 1. At the beginning of the study, there were no significant differences between the groups in terms of body weight, BMI, AC and WHR (P > 0.05). After 12 weeks of intervention, significant differences were found between the groups in BMI (P = 0.030), and AC (P = 0.005). Within-group comparisons showed that both groups experienced significant changes in body weight, BMI, and AC. However, a significant difference in WHR was seen only in the intervention group (0.93 ± 0.049–0.90 ± 0.046, P < 0.001) compared to the control group (0.93 ± 0.06–0.92 ± 0.05, P = 0.30).

The data on dietary intake and physical activity (MET.hr/day) is shown in Table 2. A significant difference in physical activity was observed between the two groups at both the beginning and the end of the study (P < 0.05). However, within-group comparisons did not show any significant differences. In terms of other variables, significant differences between the groups were found in all variables, except for Selenium (P = 0.673) and Vitamin E (P = 0.545) at the beginning of the trial. The intervention group showed a significant change in PUFA- w-6 (-2.78 ± 2.00 vs. -1.41 ± 1.32; P = 0.013) compared to the control group. Within-group comparisons represented significant reductions in total fat (82.78 ± 22.06–66.77 ± 24.37, P = 0.003), SFA (23.58 ± 9.38–18.81 ± 8.00, P = 0.013), and Vitamin E (16.13 ± 3.69–13.25 ± 3.48, P = 0.007) consumptions in the control group compared to the intervention group.

The liver parameters assessment findings are presented in Table 3. At baseline, the values for ALT (P = 0.363) and AST (P = 0.395) did not differ significantly between the two groups. The level of GGT significantly reduced in the intervention group compared to the control group ( -5.71 ± 12.46 vs. -1.03 ± 9.53). After the intervention, significant reductions were observed in the intervention group compared to the control group in ALT (-15.23 ± 18.30 vs. -4.73 ± 13.12, P = 0.039), AST (-7.52 ± 8.31 vs. -3.47 ± 3.11, P = 0.047) and steatosis score (-68.57 ± 30.94 vs. -30.19 ± 29.49, P = < 0.001). According to group comparisons, the results showed that the fibrosis score decreased significantly in the intervention group (5.97 ± 1.83 to 5.03 ± 1.25 kPa, P = 0.001) compared to the control group (7.43 ± 2.48 to 6.99 ± 2.22 kPa, P = 0.083). Both groups showed a significant reduction in Steatosis score/CAP, but the reduction in the intervention group was significantly greater than that in the control group ( -68.57 dB/m .vs -30.19 dB/m). The only meaningful differences were observed after adjusting for BMI and AC in AST (P = 0.003) and fibrosis score (P = 0.004).

The intervention group showed a significant decrease in TG concentrations (171.00 ± 89.06 to 138.47 ± 92.06 mg/dL, P = 0.049), in comparison to the control group (Table 3). However, there were no significant changes in FBS, HDL-C, TC, hs-CRP and LDL-C in either group (P > 0.05). Significantly differences in the results of insulin and HOMA-IR were seen in both the intervention and control groups.

Discussion

This is the first study that evaluated the effects of the TRF + DASH diet on obesity index, liver parameters, glycemic indices, lipid profile, and inflammation among patients with MAFLD in comparison with the control diet. The superiority of the TRF + DASH diet over the control diet was observed in the reduction of BMI, abdominal circumference, ALT, AST, hepatic fibrosis, and steatosis; however, this superiority effect was diminished in the case of glycemic, and lipid indices, and inflammation.

The beneficial effects of TRF on patients with MAFLD have been reported in previous studies19,20. In such a way TRF significantly has improved liver stiffness, liver steatosis, waist circumference, visceral fat volume and insulin resistance in these patients. Enhanced fatty acid mobilization and ketone body production, the stimulation of browning in white adipose tissue, increased insulin sensitivity, lowering of leptin and increased human growth hormone, ghrelin and adiponectin circulating levels, improved autophagy by sirtuin-1 activity stimulation, modification of apoptosis and a shift in the gut microbiota composition are possible metabolic pathways explaining the beneficial effects of TRF on patients with MAFLD36,37. However, Cai et al.‘s study reported that adherence to the TRF regime with ad libitum intake on feeding day did not improve liver stiffness in 176 patients with MAFLD38. Moreover, Wei et al.‘s study was conducted to compare the effectiveness of two diets with equal calorie restriction, one with a time limit on food intake (eating with a time limit) and the other with the usual timing of meals in patients with MAFLD. The results of this study showed that compared to receiving meals at the usual time, applying a time restriction on food intake (eating period from 8:00 am to 4:00 pm) is not effective in reducing intrahepatic triglyceride content in patients with MAFLD. In this study, both diets were equally effective in changes in plasma glucose level, HOMA-IR, liver enzyme levels and lipid levels for 12 months39. Wei et al.‘s study results are comparable with our results. Our results showed that TRF combined with the DASH diet, can be effective on more risk factors of MAFLD including general and abdominal obesity, ALT, AST, Fibrosis score and Steatosis score.

In our study, the TRF + DASH diet was able to reduce obesity indices and liver parameters much more than the control diet. As we mentioned before, adherence to TRF increases fat burning, and this fat burning is independent of calorie intake40. In addition, adding the DASH diet has been effective in observing these results according to previous studies24,25. Because in previous studies, TRF regimes alone were not effective in reducing liver parameters for long duration39. Considering the low energy density and high dietary fiber content of the DASH diet41, following the TRF + DASH diet is more effective in increasing satiety, and reducing energy and carbohydrate intake in comparison with the control diet (as we see in Table 2). Therefore, it is not surprising that it has been able to improve obesity indices in MAFLD patients more than in the control group. The high dietary fiber content of the DASH diet41, can lead to delayed carbohydrate absorption and decrease accumulation of fat in the liver42. DASH diet contains high calcium and magnesium that can stimulate microsomal triglyceride transfer protein (MTP) in the liver43 and increasing the expression of this protein has been considered as a treatment for non-alcoholic steatohepatitis44. The standard DASH diet limits salt intake and decreased sodium negatively influenced markers of liver steatosis and fibrosis45. Dorosti et al. reported that consumption of whole grains (healthy DASH food), beneficially affected liver enzyme concentrations, and fatty liver in patients with MAFLD46. Adding DASH to the TRF regimen is effective in solving two important challenges of the TRF regimen. Many people find a lot of appetite in the hours after fasting, especially for high-calorie foods, so individuals fully compensate during fed periods for the negative energy balance incurred during extended periods of fasting between eating bouts47. Furthermore, the DASH diet can be effective in reducing this desire to eat by increasing the feeling of fullness. Long fasting in a TRF diet can reduce the quality of a person’s diet and nutrient intake48. Also, the high nutrient density of the DASH diet49 can help in solving this problem and therefore, the combination of these two regimens becomes more clinically important.

Limitations of our study should be addressed. Certainly, a longer intervention period not only provides the possibility of examining the chronic effects of this type of combined diet but also provides the possibility of evaluating the level of continuous adherence to the TRF + DASH diet in the long term. Adding another intervention group to the study that was only affected by the TRF regimen was very helpful in comparing and interpreting the results. The present study also had several strengths; the RCT design of this study is a practical method that leads to the development of evidence-based clinical recommendations. Combining TRF with the DASH diet is a new nutritional strategy that has been investigate in this study for the first. The TRF program can be considered a convenient and sustainable diet50. The DASH diet is also a flexible diet that is easy to follow because it does not restrict entire food groups. The DASH eating plan is easily adaptable to other styles of eating and dietary preferences51. Therefore, the combination of these two diets can be easily used in clinical practice.

Conclusions

In MAFLD patients, TRF (16/8) in combination with a DASH diet is superior to a low-calorie diet in promoting obesity indices, and hepatic steatosis and fibrosis. Further long-term investigations are needed to draw definitive conclusions.

Data availability

The data are available upon request to corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- ALT:

-

alanine aminotransferase

- AST:

-

aspartate aminotransferase

- BMI:

-

body mass index, CAP, controlled attenuation parameter

- DASH:

-

dietary approach to stop hypertension

- FBS:

-

fasting blood sugar

- GGT:

-

γ-glutamyl transferase

- HDL-C:

-

high-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- HOMA-IR:

-

homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance

- hs-CRP:

-

high-sensitive C-reactive protein

- LDL-C:

-

low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- MAFLD:

-

metabolic associated fatty liver disease, NAFLD, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

- QUICKI:

-

quantitative insulin sensitivity check index

- TC:

-

total cholesterol

- TG:

-

triglycerides

- TRF:

-

time restricted feeding

References

Younossi, Z. et al. Global burden of NAFLD and NASH: trends, predictions, risk factors and prevention. Nat. Reviews Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 15 (1), 11–20 (2018).

Sporea, I. et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Status Quo. J. Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 27 (4), 439–448 (2018).

Sheth, S. G., Gordon, F. D. & Chopra, S. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Ann. Intern. Med. 126 (2), 137–145 (1997).

Piscaglia, F. et al. Clinical patterns of hepatocellular carcinoma in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a multicenter prospective study. Hepatology 63 (3), 827–838 (2016).

Perumpail, B. J. et al. Clinical epidemiology and disease burden of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 23 (47), 8263–8276 (2017).

Burra, P. et al. Clinical impact of sexual dimorphism in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). Liver Int. 41 (8), 1713–1733 (2021).

Targher, G., Day, C. P. & Bonora, E. Risk of cardiovascular disease in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. N Engl. J. Med. 363 (14), 1341–1350 (2010).

Calzadilla Bertot, L. & Adams, L. A. The natural course of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 17(5), 774 (2016).

Trojak, A. et al. Serum pentraxin 3 concentration in patients with type 2 diabetes and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Pol. Arch. Intern. Med. 129 (7–8), 499–505 (2019).

Sheka, A. C. et al. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a review. Jama 323 (12), 1175–1183 (2020).

Rahimlou, M., Ahmadnia, H. & Hekmatdoost, A. Dietary supplements and pediatric non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Present and the future. World J. Hepatol. 7 (25), 2597–2602 (2015).

Vahid, F. et al. Association between Index of Nutritional Quality and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: the role of vitamin D and B Group. Am. J. Med. Sci. 358 (3), 212–218 (2019).

Varkaneh Kord, H. et al. The influence of fasting and energy-restricted diets on leptin and adiponectin levels in humans: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Nutr. 40 (4), 1811–1821 (2021).

Panda, S. Circadian physiology of metabolism. Science 354 (6315), 1008–1015 (2016).

Di Francesco, A., Di Germanio, C., Bernier, M. & de Cabo, R. A time to fast. Science 362 (6416), 770–775 (2018).

Mattson, M. P., Moehl, K., Ghena, N., Schmaedick, M. & Cheng, A. Intermittent metabolic switching, neuroplasticity and brain health. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 19 (2), 63–80 (2018).

Longo, V. D., Panda, S. & Fasting Circadian rhythms, and Time-restricted feeding in healthy lifespan. Cell. Metab. 23 (6), 1048–1059 (2016).

Moro, T. et al. Effects of eight weeks of time-restricted feeding (16/8) on basal metabolism, maximal strength, body composition, inflammation, and cardiovascular risk factors in resistance-trained males. J. Transl Med. 14 (1), 290 (2016).

Kord Varkaneh, H. et al. Effects of the 5:2 intermittent fasting diet on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a randomized controlled trial. Front. Nutr. 9, 948655 https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2022.948655 (2022).

Kord-Varkaneh, H., Salehi-Sahlabadi, A., Tinsley, G. M., Santos, H. O. & Hekmatdoost, A. Effects of time-restricted feeding (16/8) combined with a low-sugar diet on the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a randomized controlled trial. Nutrition 105, 111847 (2023).

Fung, T. T. et al. Adherence to a DASH-style diet and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke in women. Arch. Intern. Med. 168 (7), 713–720 (2008).

Vogt, T. M. et al. Dietary approaches to stop hypertension: rationale, design, and methods. DASH Collaborative Research Group. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 99 (8 Suppl), S12–S18 (1999).

Razavi Zade, M. et al. The effects of DASH diet on weight loss and metabolic status in adults with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a randomized clinical trial. Liver Int. 36 (4), 563–571 (2016).

Sangouni, A. A., Hosseinzadeh, M. & Parastouei, K. The effect of dietary approaches to stop hypertension (DASH) diet on fatty liver and cardiovascular risk factors in subjects with metabolic syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Endocr. Disorders. 24 (1), 126 (2024).

Sangouni, A. A. et al. Dietary approaches to stop hypertension (DASH) diet improves hepatic fibrosis, steatosis and liver enzymes in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Nutr. 63 (1), 95–105 (2024).

Choi, J. H., Sohn, W. & Cho, Y. K. The effect of moderate alcohol drinking in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 26 (4), 662–669 (2020).

Eslamparast, T. et al. Synbiotic supplementation in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 99 (3), 535–542 (2014).

Mifflin, M. D. et al. A new predictive equation for resting energy expenditure in healthy individuals. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 51 (2), 241–247 (1990).

Ainsworth, B. E. et al. Compendium of physical activities: an update of activity codes and MET intensities. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 32 (9 Suppl), S498–504 (2000).

Gersovitz, M., Madden, J. P. & Smiciklas-Wright, H. Validity of the 24-hr. Dietary recall and seven-day record for group comparisons. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 73 (1), 48–55 (1978).

Karvetti, R. L. & Knuts, L. R. Validity of the 24-hour dietary recall. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 85 (11), 1437–1442 (1985).

Moody, A. Adult anthropometric measures, overweight and obesity. Health Surv. Engl. 1, 1–39 (2013).

Franssen, F. M. et al. New reference values for body composition by bioelectrical impedance analysis in the general population: results from the UK Biobank. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 15 (6), 448e1–448e6 (2014).

Duren, D. L. et al. Body composition methods: comparisons and interpretation. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2 (6), 1139–1146 (2008).

Hernandes, V. V., Barbas, C. & Dudzik, D. A review of blood sample handling and pre-processing for metabolomics studies. Electrophoresis 38 (18), 2232–2241 (2017).

Vasim, I., Majeed, C. N. & DeBoer, M. D. Intermittent Fasting Metabolic Health Nutrients 14(3), 631. (2022).

Mirrazavi, Z. S. & Behrouz, V. Various types of fasting diet and possible benefits in nonalcoholic fatty liver: mechanism of actions and literature update. Clin. Nutr. 43 (2), 519–533 (2024).

Cai, H. et al. Effects of alternate-day fasting on body weight and dyslipidaemia in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a randomised controlled trial. BMC Gastroenterol. 19 (1), 219 (2019).

Wei, X. et al. Effects of Time-restricted eating on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: the TREATY-FLD randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw. Open. 6 (3), e233513 (2023).

Hatori, M. et al. Time-restricted feeding without reducing caloric intake prevents metabolic diseases in mice fed a high-fat diet. Cell. Metab. 15 (6), 848–860 (2012).

Azadbakht, L., Surkan, P. J., Esmaillzadeh, A. & Willett, W. C. The Dietary approaches to stop hypertension eating plan affects C-reactive protein, coagulation abnormalities, and hepatic function tests among type 2 diabetic patients. J. Nutr. 141 (6), 1083–1088 (2011).

Rooholahzadegan, F. et al. The effect of DASH diet on glycemic response, meta-inflammation and serum LPS in obese patients with NAFLD: a double-blind controlled randomized clinical trial. Nutr. Metab. (Lond). 20 (1), 11 (2023).

Cho, H. J. et al. The possible role of Ca2 + on the activation of microsomal triglyceride transfer protein in rat hepatocytes. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 28 (8), 1418–1423 (2005).

Pereira, I. V., Stefano, J. T. & Oliveira, C. P. Microsomal triglyceride transfer protein and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Expert Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 5 (2), 245–251 (2011).

da Silva Ferreira, G., Catanozi, S. & Passarelli, M. Dietary sodium and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review. Antioxid. (Basel) 12(3), 599. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox12030599 (2023).

Dorosti, M., Jafary Heidarloo, A., Bakhshimoghaddam, F. & Alizadeh, M. Whole-grain consumption and its effects on hepatic steatosis and liver enzymes in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a randomised controlled clinical trial. Br. J. Nutr. 123 (3), 328–336 (2020).

Rynders, C. A. et al. Effectiveness of intermittent fasting and time-restricted feeding compared to Continuous Energy Restriction for Weight Loss. Nutrients 11(10), 2442. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11102442 (2019).

Collier, R. Intermittent fasting: the next big weight loss fad. Cmaj 185 (8), E321–E322 (2013).

Steinberg, D., Bennett, G. G. & Svetkey, L. The DASH Diet, 20 years later. Jama 317 (15), 1529–1530 (2017).

Soliman, G. A. Intermittent fasting and time-restricted eating role in dietary interventions and precision nutrition. Front. Public. Health. 10, 1017254 (2022).

Suri, S. et al. DASH dietary pattern: a treatment for non-communicable diseases. Curr. Hypertens. Rev. 16 (2), 108–114 (2020).

Acknowledgements

Thanks to all the participants who gave their time and energy to this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.H.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Resources, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing, Visualization, Project Administration, Funding Acquisition. M.N.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal Analysis, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing. A.S.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing. G.K.: Conceptualization, and Methodology. B.N., M.G., M.S., M.R.S., N.K., and H.P.: Investigation.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Financial support

This work was supported by a grant from Shahid Beheshti University of Medical sciences.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Author contribution statement

A.H.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Resources, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing, Visualization, Project Administration, Funding Acquisition.

M.N.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal Analysis, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing.

A.S.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing.

G.K.: Conceptualization, and Methodology.

B.N., M.G., M.S., M.R.S., N.K, and H.P.: Investigation.

Ethical approval

The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the National Nutrition and Food Technology Research Institute (Ethics committee reference number IR.SBMU.NNFTRI.1402.001) and all participants signed a written informed consent form. This study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki and was performed according to ethics committee approval.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nilghaz, M., Sadeghi, A., Koochakpoor, G. et al. The efficacy of DASH combined with time-restricted feeding (16/8) on metabolic associated fatty liver disease management: a randomized controlled trial. Sci Rep 15, 7020 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88393-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88393-7