Abstract

The links between Thyroid dysfunction diseases (TDFDs) and osteoporosis (OP) has received widespread attention, but the causal relationships and mediating factors have not been systematically studied. We used two-sample Mendelian randomization (MR) analysis to elucidate the causal relationship between TDFDs and OP. Moreover, we performed mediation MR analyses to explore the role of thyroid-related hormones and OP risk factors in the association between TDFDs and OP. Two sample MR analyses showed that hyperthyroidism increased OP (OR = 1.080, 95% CI 1.026 to 1.137; P = 0.0032) risk. Hypothyroidism increases OP (OR = 1.183, 95% CI 1.125 to 1.244; P < 0.0001) risk. Furthermore, mediation analysis revealed that TSH mediated 5.314% of the relationship between hypothyroidism and OP. In contrast, FT4 mediated 9.670% of the relationship between hyperthyroidism and OP. In European populations, TDFDs may increase OP risk. TSH mediates in the causal association between hypothyroidism and OP, and similarly, FT4 mediates in the causal link between hyperthyroidism and OP. Our findings underscore the significance of improving integrative care for individuals with TDFDs to mitigate the risk of OP. It is essential to maintain stable levels of thyroid hormones and closely monitor bone health to effectively mitigate and prevent OP.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Osteoporosis (OP) represents a prevalent metabolic anomaly affecting bone metabolism, marked by degradation in the microarchitecture of bone tissue and diminished bone mineral density (BMD). These changes significantly increase susceptibility to fragility fractures, notably in regions such as the spine, hip, and wrist1,2. In addition, according to the statistical data, worldwide OP has the highest incidence in Europe and accounts for 1.75% of the global burden, seriously jeopardizing the health and quality of life of nearly 200 million people. OP not only brings disability or even death to patients but also brings financial burdens to patients and their families3,4,5. Consequently, the timely identification and management of risk factors associated with OP are imperative to improve patient survival outcomes and alleviate the societal financial burden.

Thyroid dysfunction diseases (TDFDs) are chronic metabolic course commonly characterized by excessive or low synthesis and release of thyroid hormones6. Clinical types include hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, etc. It has been shown that hyperthyroidism decreases BMD, elevates markers of bone turnover, and consequently heightens susceptibility to fragility fractures. In contrast, hypothyroidism decreases the efficiency of bone resorption and bone turnover, slowing down the process of bone formation thereby increasing the risk of OP7,8,9. Besides, an expanding number of investigations have revealed that abnormal thyroid hormone secretion are associated with OP, such as thyroid hormone signaling is primarily mediated by the thyroid hormone receptor (TR) α 1, which plays a crucial catabolic role in modulating bone growth10,11,12. Thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) has been identified as a negative regulator of bone remodeling, exerting its effects through the activation of TSH receptors on osteoclast and osteoblast precursors. It inhibits osteoblast differentiation and the expression of type 1 collagen in a Runx2- and osterix-independent manner, predominantly by downregulating Wnt (LRP-5) and VEGF (Flk) signaling pathways13.

Recently, Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have significantly advanced our comprehension of human genetics14. These studies have successfully pinpointed numerous genetic variants across extensive sample cohorts15,16. Mendelian randomization (MR) employs genetic variants as instrumental variables (IVs) to evaluate the effects of exposures on outcomes. Compared with observational studies, MR analysis mitigates and circumvents confounding factors, while also alleviating some of the high costs, time demands, and ethical issues associated with randomized controlled trials (RCTs)17,18.

In this investigation, we conducted a two-sample MR to investigate the potential causal link between TDFDs and OP. Furthermore, we performed mediation MR analyses to identify possible mediating roles of thyroid-related hormones and risk factors for OP between TDFDs and OP. The aim of our study was to provide new insights into elucidating the etiology of OP and to shed new light on innovative approaches to clinical management and prevention strategies.

Methods

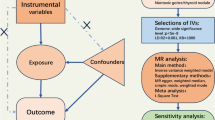

Study design

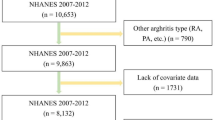

According to the latest Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology Using Mendelian Randomization (STROBE-MR), Fig. 1 illustrates the flowchart depicting the two-sample MR analysis performed in this research, and STROBE-MR is detailed in Supplementary Table 1. We used a two-sample MR to explore the causal link between TDFDs and OP. In addition, we applied mediation MR analysis to explore the role of OP risk factors and thyroid-related hormones in mediating the causal link between TDFDs and OP.

In this investigation, the GWAS summary statistics utilized were derived exclusively from publicly accessible databases focused on European populations. This approach enhances transparency and facilitates scientific scrutiny. Ethical clearance for the original GWAS summary statistics was rigorously obtained, adhering to stringent ethical standards and guidelines governing such research endeavors.

Data sources

Exposure

In this study, we conducted an analysis of three TDFDs: hyperthyroidism (ICD-10: E05), hypothyroidism (ICD-10: E03), and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (ICD-10: E06.3). Furthermore, we considered Graves’ disease (ICD-10: E05.0) as a distinct subtype of hyperthyroidism for MR analysis. GWAS summary statistics for these disorders were predominantly sourced from the investigation conducted by Sakaue et al.19. Specifically, GWAS summary statistics for hyperthyroidism comprised 3,557 cases and 456,942 controls. For hypothyroidism, the statistics included 30,155 cases and 379,986 controls. Graves’ disease was represented by 1,678 cases and 456,942 controls in the GWAS summary statistics, while Hashimoto’s thyroiditis data encompassed 15,654 cases and 379,986 controls.

Outcome

In recent years, many studies have shown that TDFDs increase OP risk20,21. Meanwhile, OP clinically presents with reduced BMD and may lead to fragility fractures22,23. In our research, we considered OP as the primary outcome with BMD and fracture as secondary outcomes. GWAS summary statistics related to OP from the FinnGen study (R10 version). FinnGen represents a significant public-private research initiative focused on genomics. To elucidate the genetic underpinnings of various diseases, the project has meticulously gathered and analyzed the genomic data of 500,000 donors from the Finnish biobank. While, GWAS summary statistics for femoral neck BMD (FN-BMD), forearm BMD (FA-BMD) and lumbar BMD (LS-BMD) from a meta-analysis performed by the Genetic Factors for Osteoporosis Consortium(GEFOS)24. This is a large international collaborative project with osteoporosis disease as the primary data source. Summary statistics for fractures occurring in various bone sites (arm, spine, leg, heel) and heel BMD (HBMD) were extracted from the initial GWAS of the UK Biobank.

Mediator

Building upon the findings of a previous investigation25, we performed a two-step MR analysis involving six thyroid function-related hormones and three risk factors associated with OP (including free Triiodothyronine (FT3), free thyroxine (FT4), Total-triiodothyronine (TT3)26, Thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH), Parathyroid hormone (PTH), TSH27, Smoking, Alcohol intake, Body mass index (BMI), and calcium levels28). Further details regarding exposure outcomes and mediators GWAS summary statistics are available in Supplementary Table 2.

Selection of the genetic variants

To ensure the robustness of MR analyses, it is essential that the selected genetic variants designated as IVs adhere to three critical assumptions. First, they should demonstrate significant associations with TDFDs. Second, these genetic variants must remain unaffected by confounding factors. Third, their effects should operate solely through their association with TDFDs, ensuring they act as valid IVs for causal inference.

For each TDFDs, we utilized its corresponding single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) as an IV, employing stringent criteria for IV selection: SNPs have to meet genome-wide significance (P < 5 × 10− 8) Based on 1000 Genomes European reference pane, SNPs exhibit low linkage disequilibrium (LD) with an r2 < 0.001 and reside at a distance greater than 10,000 kb from the locus. Subsequently, to minimize the effect of confounders, a search was performed in PhenoScanner V2 to exclude SNPs associated with outcome risk factors29. Additionally, we assessed the strength of each IV by applying the F-statistic, to avoid interference from weak instrumental variables we excluded SNPs with F-values below 1030.

The F-statistic for each SNP was computed, and the average F-statistic was determined for each of the TDFDs applying the following formula:

\(F=\frac{{{R^2}}}{{1 - {R^2}}} \times \frac{{n - k - 1}}{k}\)

\({R^2}=\frac{{{\beta ^2}}}{{{\beta ^2}+s{e^2} \times n}}\)

where n = sample size, k = number of IVs, R2 = explained variance of genetic instruments on exposure, β = effect size of SNPs, and se = standard error of effect size.

Statistical analysis

Five distinct statistical approaches were employed, including Inverse Variance Weighting (IVW), weighted median, MR-Egger, Simple mode and Weighted mode. IVW, recognized as the most commonly utilized MR method, served as the primary analytical approach in our investigation31. However, the presence of horizontal pleiotropy among SNPs in the IVW model may lead to unreliable results. Therefore, we supplemented IVW with the other four methods mentioned above to enhance the robustness of our primary MR analyses. The weighted median approach accommodates the presence of up to 50% invalid SNPs while exhibiting statistical efficacy comparable to that of the IVW method32. Although MR-Egger demonstrates reduced statistical efficacy, it offers valuable estimations in the presence of pleiotropy during Mendelian randomization analyses33. We also incorporated mode-based approaches, specifically simple mode and weighted mode, to estimate the causal effects of individual SNPs and delineate clusters31. The simple mode selects the largest cluster based on causal estimations of SNPs, while the weighted mode assigns weights to each SNP, enhancing the robustness of the causal inference34. To visualize our MR results, we plotted forest plots and scatter plots.

Additionally, a range of comprehensive sensitivity analyses were applied. Initially, in order to detect heterogeneity in MR results we applied Cochran’s Q statistic, with a p-value of < 0.05 representing consistency of results. To assess horizontal pleiotropy, we conducted MR Egger intercept tests, with a P value threshold of < 0.05 serving as an indication of the presence of horizontal pleiotropy in our findings. Subsequently, we applied MR Pleiotropy RESidual Sum and Outlier (MR-PRESSO) to identify and exclude outlier SNPs, following which IVW analysis was reiterated35. Finally, to visualize the outcomes of the sensitivity analyses, we generated funnel plots and conducted leave-one-out analyses.

To establish significant causal relationships, we employed a Bonferroni-corrected significance threshold calculated as P < 0.05/(4 exposures × 13 outcomes), yielding P < 9.62 × 10⁻⁴. P-values within the range of 9.62 × 10⁻⁴ to 0.05 were interpreted as suggestive of potential causal associations. Notably, p-values below 9.62 × 10⁻⁴ were deemed to indicate significant positive relationships 36,37. To improve our result reliability, consistency across all five MR methods was required to confirm the causal effect of the TDFDs on OP38.

Mediation analysis

To evaluate the influence of TDFDs on OP via thyroid-related hormones and OP risk factors, we conducted mediation analyses examining the causal pathways involved. The mediation proportions attributable to OP risk factors and thyroid-related hormones were calculated as the indirect effect divided by the total effect [β1 × β2/β3], where β1 denotes the impact of TDFDs on both OP risk factors and thyroid-related hormones, β2 denotes the impact of OP risk factors and thyroid-related hormones on OP, and β3 denotes the direct effect of TDFDs on OP. Standard errors (SE) were computed using the Delta method, and effect estimates were derived from the two-sample MR analysis39.

Statistical analyses were peformed using R (version 4.4.0) and the R package “TwoSampleMR”, “MRPRESSO”, and “RMediation”. For the mediation MR tests, statistical significance was defined as a two-sided p-value less than 0.05.

Results

Identify potential causal TDFDs for OP

Following stringent screening protocols, we identified between 4 and 66 IVs with TDFDs (Supplementary Table 3). F-values varied from 30.04 to 559.66. Importantly, each instrumental variable (IV) exhibited an F-value exceeding 10, indicating robustness against weak instrumental variables.

According to the IVW results, we got a total of thirteen positive results including two significant positive results and eleven suggestive positive results (Figs. 2 and 3).

For hyperthyroidism, we got 4 suggestive positive results. There existed a positive causal association between hyperthyroidism and OP with pathological fracture(OR = 1.184, 95% CI 1.063 to 1.318; P = 0.0022), Postmenopausal OP with pathological fracture(OR = 1.132, 95% CI 1.005 to 1.274; P = 0.0408), and OP(OR = 1.080, 95% CI 1.026 to 1.137; P = 0.0032), indicating hyperthyroidism increases the risk of these diseases. Conversely, there was a negative causal association between hyperthyroidism and fractured heel(OR = 0.999, 95% CI 0.998 to 1.000; P = 0.0310), indicating that hyperthyroidism decreases the risk of fractured heel.

Concerning hypothyroidism, we obtained four suggestive positive results and one significant positive result. A positive causal link existed between hypothyroidism and OP with pathological fracture(OR = 1.205, 95% CI 1.093 to 1.327; P = 0.0002), drug-induced OP(OR = 1.509, 95% CI 1.197 to 1.903; P = 0.0005), OP(OR = 1.183, 95% CI 1.125 to 1.244; P < 0.0001), drug-induced OP with pathological fracture(OR = 1.345, 95% CI 1.103 to 1.640; P = 0.0034), FN-BMD (beta = 0.0256, 95% CI 0.002 to 0.049; P = 0.0005), suggesting hypothyroidism increased the risk of these conditions.

Furthermore, about Graves’ disease, we obtained one suggestive positive result and one significant positive result. There is a positive causal association between Graves’ disease and OP(OR = 1.070, 95% CI 1.026 to 1.116; P = 0.0015); Graves’ disease increased the risk of OP. On the opposite, there is a negative causal association between Graves’ disease and HBMD(beta=-0.016, 95% CI -0.022 to -0.009; P < 0.0001); Graves’ disease increases HBMD.

Finally, regarding Hashimoto thyroiditis, we got two suggestive positive results. There was a positive causal link between Hashimoto thyroiditis and OP(OR = 1.188, 95% CI 1.093 to 1.291; P < 0.0001), OP with pathological fracture(OR = 1.227, 95% CI 1.074 to 1.404; P = 0.0027); Hashimoto thyroiditis increases the risk of these diseases. A comprehensive overview of the two-sample MR results can be found in Supplementary Table 4.

Additionally, none of our two-sample MR results indicated horizontal pleiotropy; for analyses exhibiting heterogeneity, we utilized a random effects model. Comprehensive descriptions of the funnel plots, density plots, scatter plots, and leave-one-out analyses are available in the Supplementary Tables 5 and Supplementary Table 6.

Identify potential causal OP risk factors and thyroid-related hormones for OP

We utilized a two-sample MR analysis to determine the causal link respectively between OP risk factors and thyroid-related hormones and OP. Subsequently, we assessed the causal impact of TDFDs on OP factors and thyroid-related hormones.

In the first step of MR analysis, we obtained a total of two thyroid-related hormones and two risk factors causally associated with OP. Elevated FT4 (OR = 1.245, 95% CI 1.038 to 1.494; P = 1.83 × 10− 2) and TSH (OR = 1.074, 95% CI 1.003 to 1.151; P = 4.15 × 10− 2) increased OP risk. Conversely, higher BMI (OR = 0.844, 95% CI 0.757 to 0.940; P = 2.08 × 10− 3) and calcium levels (OR = 0.980, 95% CI 0.971 to 0.989; P = 2.22 × 10− 5) reduces OP risk. Other thyroid-related hormones and risk factors were not found to have a significant causal relationship with OP.

Mediation analysis

With the preceding significant exposures and significant results, we applied a two-step MR analysis to assess the mediating influence of individual thyroid-related hormones and OP risk factors between TDFDs and OP, as shown in Fig. 4. The proportion of the effect of hyperthyroidism on OP mediated through FT4 was found to be 9.670%. Similarly, hypothyroidism mediated 5.314% of the effect on OP via TSH. The results of mediation MR are presented in Table 1.

The role of OP risk factors and thyroid-related hormones as mediators in the causal link between identified TDFDs and OP. (A) Two-step MR analysis structure. β1 denotes the effect of hyperthyroidism on FT4, β2 denotes the effect of FT4 on OP, β3 denotes the effect of hyperthyroidism on OP. (B) Two-step MR analysis structure. β1 denotes the effect of hypothyroidism on TSH, β2 denotes the effect of TSH on OP, β3 denotes the effect of hypothyroidism on OP.

Discussion

Our investigation comprehensively assessed the causal and mediating relationships between TDFDs and OP. In our investigation, it was observed that both hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism showed a notable association with OP, they both lead to an increased risk of developing OP. These results are consistent with previous MR studies40,41. Moreover, through mediation MR analysis, we found that TSH was a mediator in the causal association between hypothyroidism and OP. Specifically, hypothyroidism may increase TSH secretion to raise the risk of OP42. Additionally, we found that FT4 mediates the association between hyperthyroidism and OP, suggesting that elevated FT4 levels due to hyperthyroidism may increase the risk of OP.

Lately, attention has increasingly turned to the association between TDFDs and OP, with numerous studies highlighting TDFDs as potential contributors to OP42,43. OP, a prevalent bone metabolism disorder, is closely intertwined with human endocrinology44, where thyroid hormones play a pivotal role in regulating skeletal maintenance through processes of bone resorption and formation45,46. During adolescence, chronic thyroxine deficiency can lead to permanent stature impairments47. In adults, research indicates that bone serves as a target organ for thyroid hormone receptor alpha (TRα), with triiodothyronine (T3) promoting bone loss through interactions with TRα. However, FT3 and TT3 were not causally related to OP in our two-sample MR analysis48.

Our mediation MR results suggest that hypothyroidism may be accompanied by increased TSH in the blood, which increases the risk of OP. Previous studies consistently indicate that hypothyroidism suppresses the activity of osteoblasts and osteoclasts, thereby reducing effective bone resorption. This decrease in bone resorption rates hinders bone renewal and ultimately disrupts bone formation processes, increasing susceptibility to OP 9,49. Zhang et al. showed that elevated serum levels of TSH in hypothyroid rats decrease bone formation rates, inhibit bone remodeling, and increase bone fragility. These findings are consistent with our mediation MR analysis50. Moreover, Abe et al. found that in humans, TSH inhibits osteoblast differentiation and osteoclast formation mediated by the TSH receptor (TSHR), which results in a lower rate of bone formation than bone resorption, leading to OP13. However, it is worth noting that in clinical practice, hypothyroidism sometimes does not mean low thyroid function, and some patients have normal levels of thyroid hormones in the blood51,52. In addition, in some cases hypothyroidism may also transform into hyperthyroidism, suggesting that hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism may share a common genetic basis53.

Similarly, FT4 mediates the association between hyperthyroidism and OP. The study by Bassett et al. showed that bone remodeling acts a critical role in maintaining the strength of the human bone apparatus. In hyperthyroidism, there is an increase in both bone resorption and formation rates; however, the duration of bone resorption remains unchanged while bone formation time is reduced by two-thirds. Consequently, hyperthyroid patients experience a loss of 10% of mineralized bone per remodeling cycle54. It has been found that FT4 in patients with hyperthyroidism may act on target tissues via nuclear receptors locally controlled by deiodinase thereby reducing BMD-causing OP11,55,56. Our study corroborates the above view from a genetic perspective.

The advantages of employing two-sample MR and mediation MR analyses in this investigation are manifold. Initially, a large sample size of GWAS summary statistics was utilized, with the implementation of heterogeneity and horizontal pleiotropy tests to minimize potential confounders and enhance result reliability. Moreover, focusing exclusively on European populations helped mitigate bias stemming from population heterogeneity. In addition, because this study was an MR analysis, genetic variants were generally unaffected by disease status, thereby reducing the possibility of reverse causality bias. Our study underscores the causal effect of various TDFDs on OP. Furthermore, we identified and calculated the magnitude of the mediating effect size of TSH between hypothyroidism and OP as well as the magnitude of the mediating effect size of FT4 between hyperthyroidism and OP.

Nevertheless, several limitations warrant consideration. Initially, The biological functions of the relevant genes mediated by some of the SNPs remain unclear, potentially confounding our findings. Subsequently, survivor bias is a limitation that should be taken into account as the OP population is predominantly elderly and only those who have successfully survived to old age are likely to be studied in GWAS. Additionally, our MR analyses in this investigation were restricted to only the European population, limiting the generalizability of our findings to other populations. Therefore, Further research is necessary to ascertain whether these conclusions hold across culturally diverse populations.

Conclusion

Our study used two-sample MR analysis and mediation MR analysis to explore the causal link between TDFDs and OP. We found that three thyroid-related diseases were demonstrated to be risk factors for OP. Moreover, TSH mediated the causal association between hypothyroidism and OP. It is possible that hypothyroidism is accompanied by increased TSH in the blood and thus increased risk of OP. FT4 plays a mediator role in the causal association between hyperthyroidism and OP. Hyperthyroidism may be accompanied by elevated FT4 thereby increasing the risk of OP. Our findings underscore the significance of improving integrative care for individuals with hyperthyroidism as well as hypothyroidism to mitigate the risk of OP development and alleviate associated impacts on quality of life and financial burdens. It is essential to maintain stable levels of thyroid hormones and closely monitor bone health to effectively mitigate and prevent OP.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Foger-Samwald, U., Dovjak, P., Azizi-Semrad, U., Kerschan-Schindl, K. & Pietschmann, P. Osteoporosis: Pathophysiology and therapeutic options. Excli J. 19, 1017–1037 (2020).

Cosman, F. et al. Clinician’s guide to Prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Osteoporos. Int. 25, 2359–2381 (2014).

Johnell, O. & Kanis, J. A. An estimate of the worldwide prevalence and disability associated with osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos. Int. 17, 1726–1733 (2006).

Reid, I. R. A broader strategy for osteoporosis interventions. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 16, 333–339 (2020).

Ensrud, K. E., & Crandall, C. J. Osteoporosis Ann. Intern. Med. 177, ITC1–ITC16 (2024).

Biondi, B., Kahaly, G. J. & Robertson, R. P. Thyroid dysfunction and diabetes Mellitus: Two closely Associated disorders. ENDOCR. REV. 40, 789–824 (2019).

El, H. E. H., Ghonaim, M., El, G. S. & El, A. M. Impact of Severity, Duration, and etiology of hyperthyroidism on bone turnover markers and bone Mineral Density in men. BMC Endocr. Disord.. 11, 15 (2011).

Vestergaard, P., Mosekilde, L. & Hyperthyroidism Bone Mineral, and fracture Risk–A Meta-analysis. Thyroid 13, 585–593 (2003).

Farebrother, J., Zimmermann, M. B. & Andersson, M. Excess iodine intake: Sources, Assessment, and effects on thyroid function. Ann. Ny Acad. Sci. 1446, 44–65 (2019).

Nehls, V. Osteoarthropathies and Myopathies Associated with disorders of the thyroid endocrine system. DEUT MED. WOCHENSCHR. 143, 1174–1180 (2018).

Bassett, J. H. & Williams, G. R. Role of thyroid hormones in skeletal development and bone maintenance. ENDOCR. REV. 37, 135–187 (2016).

Bassett, J. H. et al. Thyroid status during skeletal development determines adult bone structure and mineralization. Mol. Endocrinol. 21, 1893–1904 (2007).

Abe, E. et al. Tsh is a negative Regulator of skeletal remodeling. Cell 115, 151–162 (2003).

Mountjoy, E. et al. An Open Approach to systematically prioritize causal variants and genes at all published human Gwas Trait-Associated loci. Nat. Genet. 53, 1527–1533 (2021).

Morris, J. A. et al. An Atlas of genetic influences on osteoporosis in humans and mice. Nat. Genet. 51, 258–266 (2019).

Teumer, A. et al. Genome-wide analyses identify a role for Slc17a4 and aadat in thyroid hormone regulation. Nat. Commun. 9, 4455 (2018).

Larsson, S. C., Butterworth, A. S. & Burgess, S. Mendelian randomization for Cardiovascular diseases: Principles and applications. Eur. Heart J. 44, 4913–4924 (2023).

Skrivankova, V. W. et al. Strengthening the reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology using mendelian randomization: The Strobe-Mr Statement. JAMA-J AM. MED. ASSOC. 326, 1614–1621 (2021).

Sakaue, S. et al. A Cross-population Atlas of Genetic associations for 220 human phenotypes. NAT. GENET. 53, 1415–1424 (2021).

Lee, K. et al. Subclinical thyroid dysfunction, bone Mineral Density, and osteoporosis in a middle-aged Korean Population. Osteoporos. Int. 31, 547–555 (2020).

SeyedAlinaghi, S. et al. The relationship of hip fracture and thyroid disorders: A systematic review. FRONT. ENDOCRINOL. 14, 1230932 (2023).

Yang, T. L. et al. A Road Map for understanding Molecular and genetic determinants of osteoporosis. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 16, 91–103 (2020).

Richards, J. B., Zheng, H. F. & Spector, T. D. Genetics of osteoporosis from genome-wide Association studies: Advances and challenges. Nat. Rev. Genet. 13, 576–588 (2012).

Zheng, H. F. et al. Whole-genome sequencing identifies En1 as a determinant of bone density and fracture. Nature 526, 112–117 (2015).

White, L. Osteoporosis Prevention, Screening, and diagnosis: Acog recommendations. Am. Fam Physician. 106, 587–588 (2022).

Sterenborg, R. et al. Multi-trait Analysis characterizes the Genetics of thyroid function and identifies causal associations with clinical implications. Nat. Commun. 15, 888 (2024).

Sun, B. B. et al. Genomic atlas of the human plasma proteome. Nature 558, 73–79 (2018).

Mbatchou, J. et al. Computationally efficient whole-genome regression for quantitative and binary traits. Nat. Genet. 53, 1097–1103 (2021).

Kamat, M. A. et al. Phenoscanner V2: An expanded Tool for Searching Human genotype-phenotype associations. BIOINFORMATICS 35, 4851–4853 (2019).

Burgess, S. & Thompson, S. G. Avoiding Bias from weak instruments in mendelian randomization studies. Int. J. Epidemiol. 40, 755–764 (2011).

Hartwig, F. P., Davey, S. G. & Bowden, J. Robust inference in Summary Data mendelian randomization Via the Zero Modal Pleiotropy Assumption. Int. J. Epidemiol. 46, 1985–1998 (2017).

Bowden, J., Davey, S. G., Haycock, P. C. & Burgess, S. Consistent estimation in mendelian randomization with some Invalid instruments using a weighted median estimator. Genet. Epidemiol. 40, 304–314 (2016).

Bowden, J., Davey, S. G. & Burgess, S. Mendelian randomization with Invalid instruments: Effect Estimation and Bias Detection through Egger Regression. Int. J. Epidemiol. 44, 512–525 (2015).

Walker, V. M. et al. Using the Mr-Base platform to investigate risk factors and drug targets for thousands of phenotypes. Wellcome Open. Res. 4, 113 (2019).

Chen, X. et al. Kidney damage causally affects the brain cortical structure: A mendelian randomization study. Ebiomedicine 72, 103592 (2021).

Lin, C. et al. The Causal associations of circulating amino acids with blood pressure: A mendelian randomization study. BMC Med. 20, 414 (2022).

Hu, S. et al. Causal relationships of circulating amino acids with Cardiovascular Disease: A trans-ancestry mendelian randomization analysis. J. TRANSL MED. 21, 699 (2023).

Chen, X. et al. Causal relationship between physical activity, leisure sedentary behaviors and Covid-19 risk: A mendelian randomization study. J. TRANSL MED. 20, 216 (2022).

Burgess, S., Daniel, R. M., Butterworth, A. S. & Thompson, S. G. Network mendelian randomization: using genetic variants as instrumental variables to Investigate Mediation in Causal pathways. INT. J. EPIDEMIOL. 44, 484–495 (2015).

Qi, W. et al. Investigating the causal relationship between thyroid dysfunction diseases and osteoporosis: A two-sample mendelian randomization analysis. Sci. REP-UK. 14, 12784 (2024).

Svensson, J. et al. Higher serum free thyroxine levels are Associated with increased risk of hip fractures in older men. J. BONE Min. RES. 39, 50–58 (2024).

Lee, S. Y., & Pearce, E. N. Hyperthyroidism A review. JAMA-J am. Med. Assoc. 330, 1472–1483 (2023).

Cooper, D. S. & Biondi, B. Subclinical Thyroid Disease LANCET 379, 1142–1154 (2012).

Rosen, C. J. Endocrine disorders and osteoporosis. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 9, 355–361 (1997).

Mundy, G. R., Shapiro, J. L., Bandelin, J. G., Canalis, E. M. & Raisz, L. G. Direct stimulation of bone resorption by thyroid hormones. J. Clin. Invest. 58, 529–534 (1976).

Rizzoli, R., Poser, J. & Burgi, U. Nuclear thyroid hormone receptors in cultured bone cells. Metabolism 35, 71–74 (1986).

Rivkees, S. A., Bode, H. H. & Crawford, J. D. Long-term growth in Juvenile Acquired Hypothyroidism: The failure to achieve normal adult stature. New. Engl. J. Med. 318, 599–602 (1988).

O’Shea, P. J., Bassett, J. H., Cheng, S. Y. & Williams, G. R. Characterization of skeletal phenotypes of Tralpha1 and trbeta mutant mice: implications for tissue thyroid status and T3 target gene expression. Nucl. Recept Signal. 4, e11 (2006).

Pearce, E. N., Lazarus, J. H., Moreno-Reyes, R. & Zimmermann, M. B. Consequences of Iodine Deficiency and excess in pregnant women: An overview of current knowns and unknowns. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 104 (Suppl 3), 918S–923S (2016).

Zhang, Y. et al. Chronic excess iodine intake inhibits Bone Reconstruction leading to osteoporosis in rats. J. Nutr. 154, 1209–1218 (2024).

Ushakov, A. V. Thyroid Ultrasound Pattern in primary hypothyroidism is similar to Graves’ Disease: A report of three cases. J. Med. Life. 17, 116–122 (2024).

Ushakov, A. V. Minor hyperthyroidism with normal levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor antibodies: A Case Report. J. Med. Life. 17, 236–238 (2024).

Ushakov, A. V. Conversion From Hypothyroidism to Hyperthyroidism and Back After Anti-SARS-Cov-2 Vaccination. Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism126 (2022).

Bassett, J. H. & Williams, G. R. The molecular actions of thyroid hormone in bone. Trends Endocrin Met. 14, 356–364 (2003).

Aubert, C. E. et al. Thyroid function tests in the reference range and fracture: individual participant analysis of prospective cohorts. J. Clin. Endocr. Metab. 102, 2719–2728 (2017).

Bassett, J. H. et al. Optimal bone strength and mineralization requires the type 2 iodothyronine deiodinase in Osteoblasts. P Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 107, 7604–7609 (2010).

Acknowledgements

We thank the UK Biobank, FinnGen and Genetic Factors for Osteoporosis Consortium(GEFOS) for providing the data.

Funding

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation Programme of Hubei Province (Youth Project) in 2023 (grant number 2023AFB194).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and design: YL and CS. Provision of study materials: CS, JH, and ZH. Collection and assembly of data: KX and WF. Data visualization: WF and RL. Implementation of the computer code and supporting algorithms: RL. Data analysis and interpretation: CS, JH, and RL. Manuscript writing: RL. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, R., Fan, W., Hu, J. et al. The mediating role of thyroid-related hormones between thyroid dysfunction diseases and osteoporosis: a mediation mendelian randomization study. Sci Rep 15, 4121 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88412-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88412-7