Abstract

Humans encounter both natural and artificial radiation sources, including cosmic rays, primordial radionuclides, and radiation generated by human activities. These radionuclides can infiltrate the human body through various pathways, potentially leading to cancer and genetic mutations. A study was conducted using random sampling to assess the concentrations of radioactive isotopes and heavy metals in mineral water from Iran, consumable at Arak City. Notably, specific radiation levels of Ra-226 were not detected, whereas the concentrations of Th-232, K-40, and Cs-137 were found to be below the thresholds established by the World Health Organization (WHO). The annual effective doses derived from the consumption of bottled water were significantly lower than the limits set by the United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation (UNSCEAR), thereby reducing the risk of cancer. Furthermore, heavy metals such as lead and chromium were not present in the samples, thereby contributing to the overall safety of the water. The Machine Learning (ML) models employed in this study provided accurate predictions, ensuring reliability across various demographic groups and reinforcing the robustness of the findings. Overall, the results suggest that consumable mineral water consumption poses minimal health risks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Water is crucial to human nutrition, with approximately 80% of waterborne diseases attributed to contamination1,2. To mitigate disease risks and avoid high monitoring costs due to pollutants from population growth, industrial expansion, and waste disposal, it is essential to prioritize the accessibility and affordability of clean drinking water3.

The human body is exposed to both natural and artificial radiation. Natural radiation includes cosmic rays and primordial radionuclides such as uranium, thorium, actinium, and potassium, which have long half-lives4. Artificial radiation from human activities, such as nuclear testing and accidents, includes radionuclides such as Cs-137 and Sr-905. These substances can enter the body via inhalation, ingestion, and dermal absorption6. Contaminated water can introduce internal radiation sources, leading to DNA and RNA damage and potentially causing cancer and genetic mutations7. Industrial activities also introduce heavy metals like lead, chromium, arsenic, and cadmium into the body through contaminated water, air, and food, accumulating in tissues and bones8.

Underground water that interacts with geological formations and contaminants can have higher concentrations of radioactive materials than surface water9. The global demand for bottled water has increased by 31% due to economic and safety reasons10. This study evaluated the specific activities of radioactive isotopes and heavy metal levels in bottled water and compared them with WHO health standards and findings from other countries.

Applying ML in the mineral water context involves innovative approaches to improve water quality, treatment processes, and resource management. ML algorithms can analyze data from various sensors for real-time monitoring of mineral water quality, which is essential for identifying contaminants and ensuring compliance with safety regulations11. ML models can enhance water treatment efficiency by forecasting optimal operational parameters, thereby leading to improved impurity removal and resource efficiency. In addition, ML can predict the maintenance needs of water treatment systems, thereby reducing downtime and ensuring continuous functionality11. In mineral processing, ML models can identify and assess the mineral composition of water, which is crucial for achieving the desired mineral balance in bottled water. These applications highlight ML’s transformative potential in the mineral water industry, particularly in terms of quality assurance, process optimization, and sustainable water management12.

Tackling a regression problem involves predicting a continuous outcome variable based on one or more predictor variables, which is common in fields such as finance, healthcare, and engineering. Accurate predictions require a structured approach, starting with an understanding of the data and relationships between variables through exploratory data analysis (EDA)13. Complex models such as polynomial regression, ridge regression, and lasso regression can capture nonlinear relationships and handle multicollinearity. Model evaluation and validation, such as cross-validation, ensures that the model generalizes well to unseen data, which enhances reliability14.

The goal of this study is to apply sophisticated ML models to improve prediction precision in future studies. The study also proposes recommendations for regulating radioactive isotopes and heavy metals in potable water and advocates for longitudinal studies to assess the health effects of consuming mineral water with low concentrations of radionuclides and heavy metals.

The paper is organized as follows: section “Materials and methods” details the materials, methods, and formulations for measuring radioactive isotope activity levels and reviews various ML models to identify the best regression model for predicting cancer risk. Section “Results and discussion” compares results from mineral water samples in Arak City with those predicted by ML models, discussing the most effective methods and cancer risk assessment. Finally, section “Summary and conclusion” summarizes the research findings.

Materials and methods

In this study, a random sampling technique was employed to assess the activity levels of the radioactive isotopes Ra-226, Cs-137, K-40, and Th-232 in water sourced from the consumable mineral water of Arak City. The investigation utilized commercially available mineral waters from the region. Initially, 15 samples of consumable mineral water, branded as Surprise, Miwa, Aquafina, Versailles, Deserni, Zamzam, Akarso, Vata, Damavand, Elham, Prolife, Kalis, Aqiq, Gohar, and Alis, were collected from local supermarkets in Arak. Each sample was 1.5 L of water to satisfy the measurement criteria. The samples were designated with coded identifiers WFR1-WFR15, and 800 cc samples were transferred into Marinelli beaker containers thoroughly cleaned with distilled water and alcohol. These Marinelli containers were then sealed with aquarium adhesive to eliminate any potential air exchange with the external environment and to prevent the escape of radon gas. To achieve stable equilibrium among the decay products, eight half-lives of the radon gas must elapse, which corresponds to a duration of approximately 50 days, given that the half-life of radon is 7 days. Consequently, mineral water sampling was scheduled to occur approximately 50 days after sealing15.

To investigate the heavy-metal concentration in mineral water samples using the inductively coupled plasma technique, 10 cc of each sample was transferred into Falcon containers located in the central laboratory of Arak University. The samples were subsequently pumped into an atomizer, from which they were injected into the ICP-AES device. The plasma within the device reaches a temperature of 4000 °C, which facilitates the dissociation of chemical bonds and results in light emission at various wavelengths. These wavelengths are then used to quantify the heavy metal contents in the samples. To mitigate potential chemical interferences within the apparatus, three appropriate emission lines were selected for each element, and each analysis was conducted in triplicate. Table 1 presents the characteristics of 15 consumable mineral water samples sourced from various cities, each exhibiting distinct compositions, collected from supermarkets in Arak City.

Sample preparation

The gamma-ray spectrometry apparatus used in the nuclear laboratory at Arak University is designed to measure the activity of radioactive nuclei with high-energy resolution. This system employs a Semiconductor and coaxial HPGe p-type detector model 30,195 BSIGCD, which boasts a relative efficiency of 30% and is equipped with 4096 analyzer channels. The energy resolution of the Co-60 gamma line, characterized by energies of 1332.520 keV and operating at a voltage of 3000 V, was recorded at 1.95 keV. The energy and efficiency calibrations in gamma spectroscopy are conducted using a Cs-137 standard source with known specific activity, and the spectrometry process is facilitated by lsrmB SI software. The signals produced in the detector are transmitted to the MCA8192 compact system via a pre-amplifier, where they are recorded in a sped format. Subsequently, WINHEX and MATLAB software were employed to convert these files into the CHN format. Following this conversion, the specific activities of radionuclides in environmental samples were assessed using GammaVision32 (EG&G Ortec). To determine background radiation and ensure that the spectra are analyzed under consistent spatial and temporal conditions, spectroscopy is performed in empty Marinelli containers, and the resulting data is subtracted from the original spectrum16.

In the central laboratory of Arak University, there exists an Inductively Coupled Plasma Atomic Emission Spectrometry (ICP-AES) instrument, specifically the 9100 Quant Plasma model, manufactured in Germany. This analytical technique is used for the detection of chemical elements in various samples. The device operates using inductively coupled plasma to generate excited atoms and ions, which subsequently emit electromagnetic radiation at characteristic wavelengths associated with specific elements. Plasma is a high-temperature source of ionized gas, typically argon. The device is maintained in the temperature range of 6000 to 10,000 K using inductive pairs of electric coils and operates at MHz frequencies. The absolute efficiency of the detector is determined by Eq. (1) based on the recorded gamma-ray spectrum.

where ε represents the absolute efficiency of the detector, Ni denotes the net count of the sub-peak corresponding to the energy Ei, and Act refers to the specific radioactivity of the standard source measured in Bq/Kg. Additionally, Pn(Ei) indicates the probability of photon emission at energy Ei, and t indicates the duration of the spectrometry measurements, expressed in seconds.

Special activities of radioactive nuclei

The specific activity of samples is assessed using gamma rays from various isotopes. For the gamma lines of Pb-214, which have an energy of 351.93 keV, and Bi-214, which have an energy of 609.31 keV, the specific activity is determined alongside those of Th-232. The gamma line from Ac-228, which exhibited an energy of 911.21 keV with an intensity of 28%, and another line at 338.32 keV with an emission percentage of 11%, was also analyzed. Additionally, the specific activity of K-40 was evaluated using its gamma line at 1460.70 keV, whereas the gamma line of Cs-137, with an energy of 661.66 keV, was employed for further assessment. The specific radioactivity of these radioactive nuclei within the samples is given by

where A denotes the specific activity of the sample expressed in Bq/kg. The term “Net Area” refers to the net area beneath the peak, while ε signifies the absolute efficiency of the detector. Additionally, BR represents the branching ratio expressed as a percentage, t indicates the sampling duration of the sample measured in seconds, and m corresponds to the mass of the sample in kilograms17.

Annual effective dose

The annual effective dose derived from the ingestion of natural and artificial radionuclides in drinking water is as follows:

The annual effective dose (AED) is expressed in sieverts per year and is calculated using the specific radioactivity of isotopes Ra-226, Th-232, K-40, and Cs-137 measured in units per liter (Bq/L). The dose conversion factor (DCFi) is defined in Sieverts per liter (Sv/Bq), and Cr represents the annual drinking water consumption for infants, children, and adults (250, 350, and 730 L, respectively18. Table 2 lists the dose conversion values of the core radioactive substances.

Potential cancer risk (ELCR)

To evaluate the potential cancer risk associated with drinking water consumption throughout an individual’s lifetime, various methodologies

The ELCR represents the lifetime cancer risk, and Dw denotes the annual effective dose for the specified age group, which is measured in Sieverts annually. The FAR indicates the duration of the target age range in years, and the RF, which is quantified as 7.3 × 10− 2, corresponds to the risk associated with one per Sv19.

Radium equivalent activity (Raeq)

The total radioactivity can be determined using Eq. (5), which expresses it concerning the radium activity (Raeq) as follows20

The specific activities of Ra-226, Th-232, and K-40 (denoted as ARa, ATh, and AK, respectively) were measured in Bq/l. The internal risk indicators (Hin) and external risk indicators (Hex) were used to assess the risk of radiation exposure associated with specific isotopes within the radon gas decay series. The values of Hex and Hin can be derived from Eqs. (6) and (7)21 as follows:

Safe drinking water

To determine the surface area of the core guide, we used22:

where GL represents the guide level of the radioactive core in drinking water, measured in becquerels per liter. IDC denotes the individual dose standard, established at 0.1 millisieverts per year. The variable q indicates the annual water consumption of adults (730 L per year, while hing refers to the dose conversion factor expressed in millisieverts. This factor was derived from the values associated with Becquerel (see Table 3).

To ensure the safety of drinking water, we implemented various measures.

The specific activity of the radioactive nuclei for the i-th radionuclide in drinking water is denoted Ci, while GLi represents the guideline level for the i-th radionuclide, as derived from Eq. (8). It is established that specific drinking water activities should not exceed a value of 1.

ML methods

A suitable regression model is essential for an effective analysis. Linear regression is one of the most straightforward and commonly employed techniques, primarily because of its simplicity in application. Furthermore, performance indicators such as Mean Squared Error (MSE) and R-squared, serve to measure prediction precision. Ultimately, it is crucial to continuously enhance the model by adjusting hyperparameters and integrating domain-specific insights, which improves performance. The refinement process is critical for developing accurate and reliable models. A systematic methodology is essential when tackling a regression problem to achieve precise and reliable outcomes. The main aim of this study was to predict AEDs and assess ELCR. The following outlines the key steps of this research:

-

(a)

Data Collection: This step acquires all pertinent data required for analysis, ensuring its relevance and comprehensiveness. The data presented in sections “Sample preparation” to “Safe drinking water” are primarily discussed in the results and discussion sections.

-

(b)

Data Preprocessing: Data preprocessing is a fundamental step in ML because it helps improve the quality of data and prepare them for modeling. In our dataset, there were no outliers or missing values. We used the one-hot encoding method to convert categorical mineral water type and age group data into numerical data.

-

(c)

Data Splitting: The dataset was divided into a 70:30 ratio, with 70% allocated for training to learn and 30% for testing to evaluate the performance of the model on previously unseen data.

-

(d)

Model Selection: Various regression models, including ridge regression, Decision Tree (DT) Regression, and Random Forest (RF) Regression, were evaluated to determine the most appropriate option. Below, each model is presented with a concise description:

Ridge Regression: Ridge regression improves linear regression by addressing multicollinearity by adding a regularization term to the ordinary least squares objective function. The L2 penalty reduces model complexity by shrinking the coefficients toward zero. Ridge regression is particularly useful for handling multicollinearity, which occurs when independent variables are highly correlated23.

DT Regression: DT regression employs a top-down, greedy-layer approach. The proposed method progressively divides a dataset into increasingly smaller subsets while simultaneously constructing an associated decision tree. The end product is a tree comprising decision and leaf nodes24.

RF Regression: RF Regression is an additive model that predicts outcomes by aggregating decisions from multiple base models. Each base model is a DT, and the final output of the RF model is the combined result of the DT. This method of using several models to enhance predictive accuracy is referred to as model ensemble24.

-

(e)

Model Training and Hyperparameter Tuning: The grid search method is used as a strategy to optimize the hyperparameters of ML models to enhance performance. This approach specifies a range of potential values for each hyperparameter, followed by an exhaustive evaluation of all possible combinations to identify the most effective configuration for improving model performance. Table 4 presents the hyperparameter configurations for three different models: Ridge, DT, and RF. These configurations were determined using a grid search technique, thereby outlining the ideal hyperparameters for each model.

-

(f)

Model Evaluation: The efficacy of the model was evaluated using various metrics, including the mean absolute error (MAE), Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), and Coefficient of Determination (R²). The mean absolute error (MAE) quantifies the disparity between the actual and forecasted values by computing the average of the absolute differences throughout the dataset25.

The RMSE is derived by computing the square root of the mean square error (MSE). The MSE quantifies the disparity between the actual and predicted values by squaring the mean of the differences throughout the dataset25.

Coefficient of Determination (R2): R2 denotes the coefficient of determination, which serves as an indicator of the degree to which the observed values align with the original values. The coefficient ranges from 0 to 1 and can be interpreted as a percentage. A higher R2 value indicates a superior model performance25.

-

(g)

Selecting the Best Model and Result Interpretation:

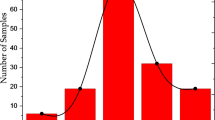

Figure 1 presents a comparative analysis of the error metrics: MAE and RMSE across three ML models: RF, Decision Tree, and Ridge models. These metrics are critical for assessing the accuracy of regression models by quantifying the discrepancies between actual and predicted values. The MAE is represented by blue bars, and it quantifies the average absolute deviation between the actual and predicted values, regardless of error signs. A lower MAE typically indicates a more precise model. In this analysis, the RF model exhibits the lowest MAE, indicating superior accuracy compared to the other models. In contrast, the Ridge model obtained the highest MAE, indicating a greater degree of error in its predictions. The MAE of the DT model was marginally higher than that of the RF model, reflecting its moderate performance in this context.

In contrast, the RMSE is illustrated with yellow bars and evaluates errors by assigning more penalties to larger discrepancies, which involves squaring the errors. This metric is particularly sensitive to larger errors than the MAE. The RF demonstrated the lowest RMSE, indicating high accuracy and reduced occurrence of significant errors. The ridge model, which had the highest RMSE value, tended to have larger prediction errors than the other models. Although the DT demonstrated a lower RMSE than the ridge, it still fell short of the accuracy exhibited by RF. Overall, the chart indicates that the RF outperforms both the MAE and RMSE, highlighting its effectiveness in minimizing prediction errors.

The R2 indices of the R2 index between three different ML models are displayed in Fig. 2. The RF, DT, and Ridge models were evaluated. The R2 index, also known as the “coefficient of determination,” is a crucial indicator used to assess the accuracy of regression models. This index showcases the amount of variance in the dependent variables explained by independent variables. The closer the R2 value is to 1, the better the model’s explanation of the data variance. In the graph, the RF model, represented in blue, exhibited the highest R2 value. This suggests that this model is the most accurate in prediction. RF is a complex model that combines multiple decision trees, which is typically employed in scenarios with complex data. RF can be used to identify correlations between features.

The DT model (green curve) is less accurate than the RF model. This can be attributed to the simplicity of the DT model, as it consists of a single tree rather than a combination of trees, as in the RF. Despite being less accurate than the RF, the DT model seems to outperform the Ridge model (red), which ranks last among the three models. This comparison reveals that the more intricate RF model performs better on our data and produces higher R2 values.

After evaluating the performance of several regression models based on various metrics, we found that the RF Regression model demonstrated the best results.

To assess the robustness of the results obtained from the proposed RF model, we evaluated the model stability using two methods. First, we applied small noise (mean 0, standard deviation 0.01) to the test data and compared the original \(\:{R}^{2}\) with the perturbed \(\:{R}^{2}\). Both values remained consistent at 0.9, demonstrating the model’s robustness and stability against minor input variations. These results suggest that the model can reliably maintain its predictive power, which is crucial for real-world applications in which data often contain small amounts of noise. Second, the bootstrap method was used to estimate the stability of the proposed model. Given the limited dataset size, Cross-Validation (CV) often produces unstable and high-variance results because the small subsets in each fold provide insufficient data for robust training and testing. This limitation can lead to inaccurate model performance estimation. To address this issue, the bootstrap method was employed. The proposed method repeatedly samples with replacement from the entire dataset, thereby allowing for optimal use of limited data. In this study, the bootstrap procedure was repeated 100 times, enabling the calculation of the mean and standard deviation of the performance metric \(\:{R}^{2}\). The results demonstrated a mean \(\:{R}^{2}\)of 0.89 with a standard deviation of 0.08, indicating the model’s stability. Therefore, due to its ability to deliver a more consistent and trustworthy evaluation, the bootstrap method was preferred over CV in this case.

Generally, the RF model demonstrated superior accuracy, robustness, and generalizability. As a result, the random forest model was chosen to make the final predictions. By leveraging its ability to capture complex patterns and relationships in the data, we can anticipate precise predictions for AED. Figure 3 summarizes the step-by-step process of the proposed ML regression model.

Results and discussion

The specific activities of the radioactive nuclei across all samples are presented in Tables 5, 6, 7 and 8, and Fig. 4 to facilitate the comparative analysis of the specific activity results. The annual dose received, expressed in (µSv/y) due to water consumption, is detailed for the three distinct age groups in Table 9. Figure 5 visual comparison of the dose results. Additionally, data concerning cancer risk associated with water consumption among the same three age groups are presented in Table 10, with Fig. 6 to enhance the comparative evaluation of cancer-related outcomes. Furthermore, Table 11 presents results related to radium equivalent activity, internal and external risk indices, and assessments of drinking water safety. A comparative analysis of the findings from this study and those from other countries is presented in Table 12, complemented by a comparison chart in Fig. 7.

The specific activities of 226Ra are detailed in Table 5. By applying Eq. (2), it is established that the total sampling duration for all specimens spans one day and night, totaling 86,400 s. The cumulative mass of the samples was 800 cc, equivalent to 0.8 kg. The branching ratio for 226Ra is estimated at 0.46, based on decay software analysis of 214Bi, which has an energy of 609 keV. The calculated absolute efficiency of 226Ra a is 0.015127. The net level for all samples was zero. Because the net level is a pivotal element for assessing specific activities, we conclude that the specific activity level of 226Ra across all samples is also zero.

The specific activities of 232Th are presented. Using Eq. (2), we determined that the total sampling duration for all samples was one day, equivalent to 86400 s, with a total mass of 800 cc or 0.8 kg for each sample, as shown in Table 6. The branching ratio of 232Th, calculated using Decay software for 228Ac at an energy level of 911 keV, was estimated to be 0.28. The absolute yield for 232Th is recorded as 0.011389. Among the samples, sample 7 exhibited the highest net activity (165), while sample 14 exhibited the lowest net activity ((0). Furthermore, the highest specific activity of 232Th was associated with sample 7, which was recorded at 0.748 Bq/L, whereas sample 14 had the lowest specific activity at zero.

Table 7 lists the special activity values for 40K. Using Eq. (2), it is determined that the total sampling duration for all samples amounts to one day and night, equivalent to 86,400 s. The total mass of all samples was 800 cc (0.8 kg. The branching ratio for 40K was computed using decay software, yielding an energy value of 1460 keV and an estimated branching ratio of 0.1. The absolute efficiency for 40K was calculated as 0.008009. Among the samples, sample 9 exhibited the highest net level (413), while sample 14 exhibited the lowest net level (zero). The most significant specific activity for 40K was associated with sample 9, which measured 7.460 becquerels per liter, whereas sample 14 had the lowest specific activity, recorded as zero.

Table 8 lists the specific activities of 137Cs. Utilizing Eq. (2), it is determined that the total sampling duration for all samples is one day, equivalent to 86,400 s, with a total mass of 800 cc or 0.8 kg for each sample. The branching ratio of 137Cs was estimated to be 0.94 based on an energy level of 661.66 keV using decay software. The absolute efficiency for 137Cs is recorded at 0.0139. Among the samples, sample 7 exhibited the highest net level (134), while sample 14 exhibited the lowest net level (0). The specific activity of 137Cs was highest in sample 7, with a value of 0.148 becquerels per liter, whereas sample 14 had the lowest specific activity, recorded as zero.

The data presented in Fig. 4 indicate that the mineral water samples exhibited the highest levels of radioactivity associated with the elements 40K, 232Th, and 137Cs. The concentration of 226Ra was recorded as zero across all samples, which is significant given that 98.5% of radiation-related damage is attributed to 226Ra. Consequently, the concentration of radium emerges as a critical parameter for mineral water factories seeking licensure from the Ministry of Health.

The information provided in Table 8 reveals that the annual effective dose for infants ranged from zero (as observed in sample 14) to 0.130 microsieverts (as recorded in sample 7. Additionally, the maximum effective dose was lower than the observed dose in infants. The annual effective dose for the pediatric population ranged from zero microsieverts, noted in sample 14, to 0.182 microsieverts (n = 7). Moreover, the maximum effective dose for children, as indicated by UNSCEAR, is also comparatively lower. Lastly, the annual effective dose for the pediatric age group ranged from zero microsieverts (associated with sample 14) to 379 microsieverts (associated with sample 7. Furthermore, the peak effective dose for children remains below the UNSCEAR threshold.

Figure 5 compares the dosages received by infants, children, and adults. The annual consumption of drinking water is 730 L for adults, 350 L for children, and 250 L for infants. Consequently, the dosage received by each age group decreased in the following order: adults, children, and infants. The highest doses for all three age groups were associated with sample 7.

The data presented in Table 10 indicate that the cancer risk factor for newborns ranges from 0 to 71,010− 6, demonstrating variability. The cancer risk coefficient for the same age group spans from 0 to 99,510− 6, also exhibiting variability. Additionally, the cancer risk coefficient for infants, within the range of 0–2070, is on the order of 10− 6, highlighting its variable nature.

Figure 6 illustrates the comparative risk of cancer among the analyzed samples, including adults, infants, and children. This assessment was influenced by the critical AED variable. Notably, the effective dose received was correlated with a decreased cancer risk among the following age groups: adults, children, and infants.

The equivalent radium activity is presented as an average of 0.61, in Table 11. The internal and external indelibilities are consistent, attributable to the uniform specific activity of radium-226, resulting in identical and low values. Furthermore, the analysis indicates that the water safety levels across all samples are below one, suggesting that there is no significant health risk associated with these findings.

To facilitate the comparison of the findings of this study, Table 12 presents the specific activity results of radioactive nuclei in bottled water from various countries. The outcomes of this investigation align well with those reported in other countries and the values established by international organizations. Consequently, it can be inferred that the radiation levels in the bottled water consumed by Arak residents do not pose any health risks. As illustrated in Fig. 7, except for Malaysia and Nigeria, the levels of radioactive nuclei activity in all other countries fell below the thresholds established by the World Health Organization. Furthermore, research on bottled water consumption in Arak City, Iran, indicates that the presence of radioactive nuclei does not represent a risk to human health.

This illustration presents the Actual versus Predicted chart for the RF model applied to the regression analysis. A chart serves as a valuable tool for juxtaposing the model’s predicted values against the actual observed values, thereby facilitating the assessment of the regression model’s efficacy. In this representation, points that align closely with the 45-degree line indicate that the model’s predictions are nearly equivalent to the actual values. A significant number of points clustered around this line, particularly at the lower end of the X-axis, suggesting a high level of accuracy in this region. The minimal dispersion of most points on the chart indicates that the RF model effectively captured the complexities of the data and produced reliable predictions. Nevertheless, a few points deviating from the diagonal line may reflect specific characteristics of the data that warrant further investigation. Overall, this chart demonstrates that the RF model has excelled in this regression task, achieving commendable accuracy in its predictions of actual values.

Figure 8 displays the actual and predicted values for the RF model used in our regression analysis. This chart is a useful tool for comparing the model’s predicted values with the actual observed values, making it easier to evaluate the effectiveness of the regression model. The plot shows the actual values on the horizontal axis and the predicted values on the horizontal axis. Each point on the plot represents a specific data pair, where the actual value is compared to the predicted value.

In this representation, points that closely align with the 45-degree line indicate that the model’s predictions are nearly equivalent to the actual values. Notably, a significant number of points were clustered around this line, particularly at the lower end of the X-axis, suggesting a high level of accuracy in this region. The low scatter in most parts of this image shows that the RF model can accurately predict complex representations. However, a few points deviating from the diagonal line may reflect specific data characteristics that warrant further investigation. Overall, this chart demonstrates that the RF model has excelled in this regression task, achieving commendable accuracy in its predictions of actual values.

Table 13 compares the actual and predicted AECL and ECLR. The samples were divided into three groups: Infants, Children, and Adults. The table includes columns for FAR (75 for all samples), RF (0.073 for all samples), and CR (ranging from 0.00264 to 0.00401). These values are small decimals, indicating some form of measurement or calculation. This table compares the predicted results of our prediction model with actual values across various age categories.

Figure 9 presents a summary of the feature’s importance chart. The CR feature had the highest level of importance, indicating its crucial role in the model analysis. The “Adults” feature ranked second most significant, demonstrating a considerable effect. Mineral water types 7, 6, and 5 also had notable importance although less than CR and Adults. On the other hand, features related to infants and children were moderately important compared to the other features. This figure highlights the features that have the greatest influence on our model analysis.

Summary and conclusion

In all mineral water samples, special Ra-226 radiation levels were absent. The average Th-232, K-40, and Cs-137 concentrations were 0.311, 2.104, and 0.049 Bq/l, respectively, all below the WHO thresholds. The annual effective doses from bottled water consumption were 57.6 µSv/y for infants, 80.7 µSv/y for children, and 168 µSv/y for adults, which were significantly lower than the UNSCEAR limit of 1000 µSv/y. The cancer incidence coefficients were 316 for infants, 442 for children, and 922 for adults, indicating a cancer risk of 922 × 10–6 for a 75-year-old. Hex and Hin values ranged from 0 to 0.002, indicating no health risk. The radium equivalent activity values ranged from 0 to 1.08, aligning with global averages, with the highest level observed in the WFR7 sample. Heavy elements such as Cd, Hg, Sn, Pb, and As were detected at zero mg/L. The RF model’s performance was validated by comparing actual and predicted values, demonstrating its reliability across different age groups and enhancing the study’s robustness.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study is included in this published article.

References

Piñero Garcia, F., Thomas, R., Mantero, J., Forssell-Aronsson, E. & Isaksson, M. Radiological impact of naturally occurring radionuclides in bottled water. Food Control 130, 108302 (2021).

Dinh Chau, N. et al. Natural Radioactivity in Groundwater—a Review 47 (Isotopes in Environmental and Health Studies, 2011).

Turhan, S., Özçıtak, E., Taşkın, H. & Varinlioğlu, A. Determination of natural radioactivity by gross alpha and beta measurements in groundwater samples. Water Res. 47(9), 3103–3108 (2013).

El-Taher, A., Uosif, M. A. & Orabi, A. A. Natural radioactivity levels and radiation hazard indices in granite from Aswan to Wadi El-Allaqi southeastern desert, Egyptian. Radiat. Prot. Dosimetry 124(2), 148–154 (2007).

Harb, S., El-Kamel, A. H., Zahran, A. M., Abbady, A. & Ahmed, F. A. Assessment of natural radioactivity in soil and water samples from Aden Governorate South of Yemen Region. Int. J. Recent. Res. Phys. Chem. Sci. (IJRRPCS) 1(1), 1–7 (2014).

Pourimani, R. & Nemati, Z. Measurement of radionuclide concentration in some water resources in Markazi province, Iran. Iran. J. Med. Phys. 13(1), 49–57 (2016).

Hossain, M. A. et al. Natural radioactivity levels and radiological risk assessment of surface water of wetland Tangur Haor, Sunamganj District, Bangladesh. J. Radiation Nuclear Application 4(2), 117–125 (2019).

Massaro, E. J. Handbook of Human Toxicology, National Health and Environmental Effects Research Laboratory (CRC, 1997).

Rangela, J. D. et al. Radioactivity in bottled waters sold in Mexico. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 56(6), 9. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0969-8043(02)00047-7 (2002).

Ranjbar, H. & Bagheri, R. Radioactivity assessment and lifetime risk survey from bottled water in Iran. Iran. J. Public. Health 22, 3. https://doi.org/10.47176/ijpr.22.3.21383 (2022).

Tsimpidi, I., Sartjärvi, R., Juntunen, P. & Nikolakopoulos, G. A survey on machine learning approaches in water analysis. In Artificial Intelligence Applications and Innovations. AIAI 2024 IFIP WG 12.5 International Workshops. AIAI 2024. IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology, vol 715 (eds. Maglogiannis, I. et al.) (Springer, 2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-63227-3_1.

Long, T., Zhou, Z., Hancke, G., Bai, Y. & Gao, Q. A review of artificial intelligence technologies in mineral identification: classification and visualization. J. Sens. Actuat. Netw. 11(3), 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/jsan11030050 (2022).

Montgomery, D. C., Peck, E. A. & Vining, G. G. Introduction to Linear Regression Analysis 5th edn (Wiley, 2012).

Chatterjee, S. & Simonoff, J. S. Handbook of Regression Analysis (Wiley, 2013).

International Atomic Energy Agency. Collection and Preparation of Bottom Sediment Sample for Analysis of Radionuclides and Trace Elements (IAEA-TECDOC-1360, IAEA, 2003).

Aziz, A. In International Atomic Energy Agency, Vienna, Methods of Low-Level Counting and Spectrometry Symposium, Berlin 221 (1981).

Singh, P., Rana, N., Azam, A., Naqvi, A. & Srivastava, D. Levels of uranium in waters from some Indian cities determined by fission track analysis. Radiat. Meas. 26(5), 683–687 (1996).

WHO. Guidelines for drinking water quality. WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data NLM Classification (2011).

Karabidak, S. M., Kaya, A. & Kaya, S. Cancer risk analysis of some drinking water resources in Gumushane, Turkey. Sustainable Water Resour. Manage. 5, 1939–1949. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40899-019-00338-x (2019).

Mheemeed, A., Najam, L. & Khatab, A. Transfer factors of 40K, 226Ra, 232Th from soil to different types of local vegetables, radiation hazard indices, and their annual doses. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 302, 87–96. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10967-014-3259-y (2014).

Ahmed, N. K. et al. Comparative study of the natural radioactivity of some selected rocks from Egypt and Germany. Indian J. Pure Appl. Phys. 44, 209–215 (2006).

Pourimani, R., Karimi, S. & Mohebian, M. Measurement of specific radioactivity of natural and artificial radioactive nuclei and calculation of radiological hazards related to them in drinking water of Isfahan region. Iran. J. Radiation Saf. Meas. 9(1), 21–32 (2021).

Tran, T. K. et al. Initial coin offering prediction comparison using Ridge regression, artificial neural network, random forest regression, and hybrid ANN-Ridge. In Mendel, Brno University of Technology (2023).

Acharya, M. S., Armaan, A. & Antony, A. S. A comparison of regression models for prediction of graduate admissions. In 2019 International Conference on Computational Intelligence in Data Science (ICCIDS) 1–5 (IEEE, 2019).

Reddy, P. S. M. Decision tree regressor compared with random forest regressor for house price prediction in Mumbai. J. Surv. Fisheries Sci. 10(1S), 2323–2332 (2023).

Desideri, D. et al. (238)U, (234)U, (226)Ra, (210)Po concentrations of bottled mineral waters in Italy and their dose contribution. J. Environ. Radioact. 94(2), 86–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvrad.2007.01.005 (2007).

Kozlowska, B., Walencik, A. & Dorda, J. Natural radioactivity and dose estimation in underground water from the Sudety Mountains in Poland. Radiat. Prot. Dosimetry 128(3), 331–335. https://doi.org/10.1093/rpd/ncm380 (2008).

Seghour, A. & Seghour, F. Z. Radium and (40)K in Algerian bottled mineral waters and consequent doses. Radiat. Prot. Dosimetry 133(1), 7–50. https://doi.org/10.1093/rpd/ncp009 (2009).

Ajayi, O. S. & Adesida, G. Radioactivity in some sachet drinking water samples produced in Nigeria. Iran. J. Radiation Res. 7(3), 151–158 (2009).

Benedik, L. & Jeran, Z. Radiological of natural and mineral drinking water in Slovenia. Radiat. Prot. Dosimetry 151(2), 306–313. https://doi.org/10.1093/rpd/cs009 (2012).

Khandaker, M. U. et al. Radiation dose to the Malaysian population via the consumption of bottled mineral water. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 140, 173–179 (2017).

Khandaker, M. U. et al. Assessment of radiation and heavy metals risk due to the dietary intake of marine fishes (Rastrelliger kanagurta) from the Straits of Malacca. PLoS One 10, e0128790 (2015).

Wallner, G. & Jabbar, T. Natural radionuclides in Austrian bottled mineral waters. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 286, 329–334 (2010).

Altıkulaç, A., Kurnaz, A., Turhan, S. & Kutucu, M. Natural radionuclides in bottled mineral waters consumed in Turkey and their contribution to radiation dose. ACS Omega 7, 34428–34435. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.2c04087 (2022).

Ramadhan, R. M., Al-Salihi, A. & Khalaf, A. H. Measurement of radiological baseline data of the hazard radiation in bottled drinking water samples in Basrah/Iraq. Basrah J. Sci. 38(3), 544–558 (2020).

UNSCEAR. United Nations Scientific Committee on the effects of Atomic Radiation. In Sources and Effects of Ionizing Radiation Report to the General Assembly with Scientific Annexes ( United Nations Publication, 2008).

Funding

No funding was received to assist with the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Fatemeh Ranjbar: Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Writing–review & editing, Conceptualization, Validation, and Methodology. Hossein Sadeghi: Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, writing, review and editing, Supervision. Reza Pourimani: Investigation, Data curation, Conceptualization, Supervision. Soraya Khanmohammadi: Writing, review, and editing, Conceptualization, Validation, Software, Methodology.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ranjbar, F., Sadeghi, H., Pourimani, R. et al. Machine learning models for water safety enhancement. Sci Rep 15, 3841 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88431-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88431-4